|

|

|

[Page 410]

by Khave Burshtin-Bernshteyn, Israel

Translated by Tina Lunson

The days between Rosh-ha'shone and Yon-kiper, the ten days of penitence, were sad and melancholy. The sun was obstructed behind a thick cloak of clouds. She was ashamed of the trouble and shame that we, the Goworowo Jews, had gotten for no kind of sin and evil. The town had been burned, ash and debris. The refugees were concentrated at the Rits brothers' mill, located just outside the town, and it was thanks to that location it was not burned. The Rits brother had given all the rooms and residences on the estate of the mill for the burned-out and suffering townspeople. The others remaining rented rooms in the surrounding Christian houses. They clung together like sheep encircled by a pack of provoked wolves.

My family, which consisted of my father, my stepmother the Rebitsn, and myself, settled at Note Rits's in a comfortable, airy room. It is not possible to relate the sincerity and open-heartedness with which the family Rits approached my father of blessed memory. As a rule, everyone behaved as if we were one family. We literally shared what little we had, and one helped another in whatever way he could. The troubles and experiences united everyone.

The holy day of Yon-kiper neared. There was nothing to feast on before the Yon-kiper fast. All of the flour reserves from the mill had been taken by the Germans. Everyone was worried, and my father was very upset that Jews would not be able to do the mitsve of eating on the eve of Yon-kiper and could, heaven forbid, fall to temptation or become weakened on Yon-kiper itself. An idea occurred to me: I would go Sukhtshits where the former “mayor” Karolak lived – a great lover of Yisroel – and beg him for food. I told my father my idea. He hesitated. It was a long way to Sukhtshits. I would have to go by foot, and the roads were considered very dangerous. He pondered it for a long time, and glanced at me with fatherly concern. After a while he arrived at a decision. “Go, my child, and bring food for all the Goworowo Jews.” I no longer felt any fear, and I set out on the road to Sukhtshits.

[Page 411]

I took Ester Leye Gemora with me and we sneaked along side roads, but feeling the blessings that accompanied our important mission. To our great happiness we did not encounter any Germans along the way, and we were successful in arriving at “mayor” Karola's house. We met him sitting in his simple house with his family. He fixed his pair of wondering eyes on us, as if he had seen living corpses. He ordered his wife to bake some bread, and meanwhile he asked us with great interest how all his Jewish friends were doing. First of all, he gave us food to eat to our satiety, and the whole time he comforted us with the thought that we would overcome this trouble. The bread was ready around lunchtime. We had to hurry in order to bring the bread before evening, for the last meal before the fast. Karolak gave us six large loaves of bread, and he gave me a special bread and things for my father the Rov. He asked us that if we were caught, we should not say that he had given it to us. With tears in his eyes, he accompanied us to the back road and told us to guard ourselves against the Poles just as from the Germans.

We got back to the mill in peace. All the Jews were standing on the road and looked at us as though we were the Messiah. In my father's eyes I could recognize signs of pain and a sting of conscience about how he had allowed us to make such a dangerous trip. But the joy of the return, to say nothing of the bread, covered the torture of his soul. The joy of all the people was huge. My father distributed the bread, to each his portion. The smell of the fresh bread quickened everyone's appetites, and each rejoiced with the portion that he had received from the Rov, for himself and for his family after the fast.

We sat down to the erev Yon-kiper “feast”. Everyone was sunken in thoughts: not long ago, one was a proprietor, of himself, a home, a family; and now, concerned for the future, and meanwhile such darkness; German murderers who seek Jewish blood, the Polish neighbors who became enemies overnight, and here we are homeless, dark before our eyes. Who knows if the Germans will want to use the holy Yon-kiper to torment the few Jews remaining in town, a little more. Our family was especially terrified, because the news had reached us that the Germans were searching around for my father, and it had already been said that one of the priests had denounced him, telling the Germans that the Rov was staying at the Rits brothers' mill.

Then we heard an automobile driving into the yard of the mill and heard wild screaming from the Germans. They ordered Note Rits to turn over the Rov. My father hid in the attic for a short while. But hearing that the Germans were not going away, he came out of his hiding place and bravely faced the Germans murderers. Several S.S. soldiers began to beat him and yank at his beard. An officer gave

[Page 412]

the Rov an order: In three days' time he must present the German office with several kilograms of gold and all valuables that remain among the Jews. He shot off his pistol and with wild laughter left with his band. There was panic, for where would they get gold, as there was not even one iron nail left from all their belongings. So they made a limit for the Rov, that if he did not present the gold on time – he would be shot, and here it was already Yon-kiper.

The sun slid down and went on her way. Dusk came. People asked that each should pray by himself. My father did not agree: “If one still has the merit to recite kol-nidrey with the community, one must use it.” In the large salon in Note's house they hung the window with a black cloth. The rescued Torah scrolls lay on the table. An eternal light flickered with a weak flame. People with swollen eyes slinked around like shadows. Children clung to their fathers, as they could perceive the great danger. There were not any holiday prayerbooks, so everyone prayed from their hearts and said their own improvised “prayer of acquittal”. People did not plead for livelihood and pride from their children. People only pled for a bit of bald life and a quick redemption for the people of Israel.

There was not anyone to be a cantor for kol-nidrey. No one wanted to be the messenger from the community for such a broken congregation. My father began to recite kol nidrey with a broken voice. His face beamed with holiness. The women gathered in a nearby room, where the floor was wet with tears. We, the girls – myself, Libe Kosovski, Miryam Rokhl Hertsberg, the Gemora sisters and others – placed ourselves around the house outdoors, in order to sound the alarm if the Germans came near. That did not last long until we heard the sound of an automobile engine.

Germans with machine guns poured out into the yard. They chased everyone out into the yard, stood them in a row and aimed their machine guns at them. Everyone was certain that their last hour had struck. An officer called my father out from the row and said, “You “godly man” come out!” They ordered him to take a prayer book in hand, and a light. After that they called out from the lines Note Rits, Yoelke Beker, Itsele Reytshik, and pointed their loaded rifles at them. People began reciting the last confession. A younger S.S. man sprang out with a motion-picture camera and made a photo-shoot of the terrified Jews. They then shot into the air and went off to wherever they had come from.

People went back into the house to finish the prayers. Now no one wept, no one complained. This measure of trouble had already overflowed.

by Rov Yitskhak Shafran, America

Translated by Tina Lunson

The commandment “that you may remember” is said about the departure from Egypt: it is a mitsve to remember and to relate the troubles and the miracles that the Jewish people experienced in mitsrayim; and that mitsve expands over the whole life of the Jewish person – in reciting Shema Yisroel, at the sabbath kidush, in blessings, at weekly, Shabes and holiday praying, in the tfiln, in weights and balance – everywhere: So that we may remember the day of our departure from the land of Egypt.

I have already asked many Talmud scholars: is the enslavement in Egypt a comparison to the distress that the Jewish people went through under the Nazis may their names be blotted out? “No comparison” each one answered. Such enslavement , such torture, such terrible and bizarre deaths and such an enormous number of those tormented, 6 million martyrs, had not happened since the creation of the world. And the miracles of the rescued surviving remnant are also extraordinary, not to be comprehended. Every redeemed Jew can write an entire book about what kind of miracles allowed him to come alive out of the Nazi hell.

I was only under the Nazis for a few weeks, and I was twice stood against a wall to be shot. The first Yon-kiper , at two o'clock in the morning, I was with my father Reb Shleyme Shafran in Ostrov Maziecki . Two Nazis broke down the doors and came into the house. One shoved my father and me into a corner. In one hand he held a loaded revolver, and in the other hand an electric lamp. He howled in a canine voice “Money, or I shoot you now!” Of course, I gave him everything. In another room the other Nazi may their names be blotted out encountered my cousin Malke Shafran from Ostrolenke. She was them twenty years old, and a lovely woman. The Nazi wanted to rape her. But she put up a strong resistance and did not let him touch her. She told him that she was a religious woman, she would rather let herself be shot and not allow such a crime. When the Nazi came into our room he told the second Nazi that she was very stubborn “Not to be had”. When they finally left, my cousin said, “Yitskhak! I swear that he did nothing to me.” My cousin and uncle, aunt and all the children were later murdered in the Slonim slaughter. May God avenge their blood.

[Page 415]

Today we have no Teacher Moses who can give us a Torah with mitsves, remember your departure from Europe. We have no Mordkhe and Ester who will write us a megile to read even just one time a year. Let us suffice in the meantime with what we have. We have fellow landsmen who publish a memorial book. Every landsman from every town and townlet should do that. Because each town has its own “megile”. How holy is a parent's yortsayt for us Jews? What kind of shake-up happened in our town when the first-born, sainted Yerukhim Fishl Krulevitsh died before the war? How sacred for hasidim is a yortsayt for their rebi? So then what should we do to immortalize the yortsayt for our rebis, rabeyim, brothers and sisters, colleagues, good friends and the community of Yisroel together, who were so cruelly murdered as martyrs to God?

The history of the departure from Egypt began with 70 souls, from whom the Jewish people developed. The decimation of our town when the Nazis came in on Shabes the 9th of September, began with the shooting of 70 people and the burning of the whole town. What kind of “so you may remember” have the wise men of this generation invented that one must do daily, and one time a year, in order not to forget all this?

We, the first generation of the Holocaust will probably not forget. I believe that each of us, wherever we live and whatever we do, even at night in bed – see the entire destruction before our eyes. But we must also think about our children and later generations, that they not forget either!

We are prohibited, however, from despair. Too much worry is a thing for Satan, because Satan's messiah Hitler may his name be blotted out wanted to drive us to despair and resignation. But as the Holocaust was so enormous and horrible, those few survivors are united by the great and extraordinary miracles. The survivors must thank God may his name be blessed for the huge miracles and marvels that happened to them. When the miracle is greater, so the joy is the greater.

I will never in my life forget the joyous events when, after the war, I came out from the Shanghai Ghetto in China, and finally arrived in America. Of course, every man for himself. We first mourned for our parents, relatives and the shtetl Goworowo where I had spent so many years of youthful education. But I had worked for six years in the “Beys Yankev” School for Girls as manager, secretary, treasurer, and myself gave lectures for the “Basye” and “Banos” – all without pay, as a gift. And when Hitler wiped all that away, I thought to myself Master of the Universe! Has my entire work for the sake of Torah, then, gone for nothing?! No trace remains, all gone to the devil?! A little while later I found in New York the ritual slaughterer's daughter Feyge Mazes, today, Rozen, and Rivke Shtshetshina, today Rebitsn Rozental, the best of my students, members of “Banos”. My joy was beyond measure. I later found out that in Israel

[Page 416]

there were surviving members of “Banos”, the dear sisters Rokhl and Sore Zilbershteyn and others. Some members of the “Tseyrim” had also survived: the brothers Mazes in America, and others in Israel. The Rov's only son, Rov Avieyzer Burshtin, was saved. All of them had already married, had children, conducted fine orthodox Jewish homes. And other men and women from our town had been saved. We see that the devil did not exterminate everything. Jewish continuity would be secure. All in all, may it be, that we have a beginning of the redemption. After thousands of years, we are credited to return to a Jewish state. All that comforts us and cheers our lamenting hearts.

We must make an effort toward a little joy, to demonstrate to ourselves and for the whole world, that the people of Israel lives, everlasting and forever!

by A. Ben-Ir, Argentina

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

Edited by Tina Lunson

|

Tears flow from my eyes for the city of Goworowo that has shattered life. This is my native city, where I grew up and was educated. Now it is desolate, wiped off the face of the earth. Men and women, young and old, Were burned like paper, slaughtered like sheep. The hands of unclean people, Thirsty for blood, Like beasts of prey, Stabbed them with the sword. They went to death like messengers of the community, To atone with their blood for the sins of the community. They died for us, And for our children, And for all our people, For generations to come. Cursed be the murderers, their memory erased, For all our enemies among us, death awaits them, no blood will be shed, peace will prevail between people and people. |

by B. Avieyzer, Israel

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

Edited by Tina Lunson

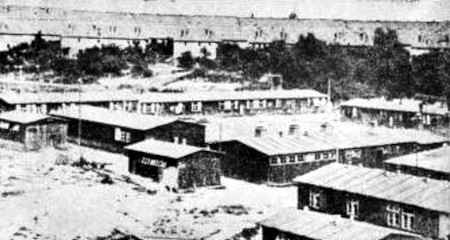

The camp in Belizin, Kielce district, contained four large manufacturing plants, where about two thousand Jews worked as forced laborers.

In this camp there were no gas chambers and incinerators like there were in extermination camps such as Auschwitz. Here, the Nazis used a different method: atrophy and annihilation through hard work and starvation. The prisoners worked hard at grueling jobs for twelve hours a day, and received food rations so meager, that the amount that should have lasted a month was barely enough for one meal.

The terrible hunger that prevailed in Belizin left its mark on the miserable detainees after only a few weeks: swollen legs, a swollen stomach, an enlarged and swollen head, etc.

The commander of the last camp was a high-ranking SS officer named Hertz, the son-in-law of an influential German general, thanks to whom he was able to escape from the front, and with the excuse of commanding the labor camp, he remained in the home front without risking his own life. He himself did not raise a hand to beat a Jew, and even prevented the “Scharführer” Buska, a sadist since his birth, from abusing the detainees in his presence - which was rare in these times - but did not lift a finger to change the killing regime in the camp; therefore, even the bravest of the detainees would not have lasted more than one year.

My place of work was in the knitting factory, where we produced and repaired woolen socks for the exterminators and the German civilian population. About four hundred Jews were employed here, divided into two shifts.

One day we noticed that the number of workers had decreased significantly and that many machines had been shut down due to lack of working hands. We were told that many were sick with the flu, but among the workers there was a rumor that this disease was a typhoid epidemic, and that the Jewish doctors, as well as the “Stormbanführer” Hertz, were trying to hide the fact, out of fear lest the camp be eliminated because of this and then Hertz will also be sent to the front.

The ranks of the workers thinned out day by day, but the amount of food did not change. The healthy ones took advantage of this opportunity: each of them filled his bowl, which was hanged by a rope around his waist, several times.

One day, while I was swallowing a large portion of food, I suddenly felt that my body was becoming heavy. I tried to get up from where I was sitting, and my head was spinning. Immediately I suspected that I was also trapped in a trap and suffered from typhus. With the rest of my strength, I dragged myself to the hospital.

The wooden shack where the patients lie down was once intended to be a stable for horses. It was about thirty meters long and nine meters wide. It had no windows but narrow portholes up the roof, through which pale and faint rays of light penetrated. On both sides of the walls stood two-story selves,

[Page 418]

and the sick were sprawled on them, crowded. Officially, the patients were under the supervision of a Jewish doctor and a nurse from among the detainees, but in reality, the nurse didn't do anything except wear a white apron and sit in the entrance hall. Neither did the doctor do much to improve the condition of the patients. And it is true that they had no possibility of helping the patients without medicinal drugs, when they alone were responsible for four hundred patients or more. Therefore, the patient himself had to take care first of all to find himself a place to lie down. If he had an acquaintance among the healthy people, who provided him with food to restore his soul, he could hold on somehow, and if not – then he laid down without food until he was well and could get up and take care of his needs; or he ended up being led by the group of gravediggers out of the camp… The quota was: thirty to fifty dead per day.

There was no more room for me on the selves, so the nurse advised me to lie down on the floor. And did I have a choice? I knelt down on the black floorboards, not far from the iron stove that stood in the middle of the hut. My bones trembled from cold and heat at the same time, I took off my clothes and put them on my fevered and frozen limbs. I wasn't left alone on the floor; soon several more patients were added and laid down next to me.

Fire burned in my body and suffocating dryness filled my throat and sparks of fire splashed against my eyes. I tried to get up, and fell from exhaustion, but with sickly stubbornness I made an effort and crawled forward to the door of the shack. There, in the corner, stood a barrel full of water. As I did not have a cup, I dipped my face in the cold water and drank…I immediately got a double “fever” and my teeth were throbbing. I returned crawling to my “bed” and fell into a deep sleep.

After days, weeks, or months – I lost any sense of time – I opened my eyes and looked around me in wonder: where am I? In the deep sleep that fell on me, that lasted for who knows how long, I was in another world, at my home, with my family, next to my friends and acquaintances, and I felt happy. I was very sorry, that my sweet dream stopped in the middle…

It was dark in the hut, and the smell of mold and rot rose in my nostrils. The floor was full of patients who were writhing in pain and asking for help, but – no one heard them.

My general feeling was very bad. The high fever did not go down, and my aching bones, which had been lying on the floor for a long time, hurt me a lot. In addition to that, I was harassed by the passers-by in the hut, who stepped on my body during their passing from place to place. More than once, someone stepped on my feet with all their weight. It didn't allow me to rest and strained my nerves to the point of exhaustion. I began thinking how to get out of the distress and be privileged, at least, to lie down in a more comfortable bed, on the planks of the shelves?

Every day, places on the shelves were vacated due to those who died or recovered, but the places that were vacated were immediately taken by patients who had the strength to get up and climb onto the shelves, or they were confiscated by the doctor for privileged patients.

I came to the conclusion that I must reach a resting place at any cost, if I don't want to lose all hope of getting out of this barn alive.

It didn't take long before I saw that not far from me, the “gravediggers” were “taking care” of one of the patients; I realized that this patient was no longer alive, I crawled closer there and I succeeded: I was the first to climb the shelf to the resting place.

[Page 419]

After I arrived at this desired place, my condition was even worse. I weakened to the point of exhaustion. I felt that I was about to die. In my previous place I could not concentrate and think about my condition, because my nerves were troubled by too much worry, that my head and feet would not be prey to the soles of those walking on me; now my nerves reached the point of disintegration and revealed to me my true condition.

One day my illness got better. I was oppressed by the feeling of loneliness, and I took out of my coat pocket a pamphlet, which contained several pages from Masekhet Ketubot. I once found it rolling around in the rag hut, and now I looked it over. At that time, the head of the “gravedigger” group happened to pass by my bed and looked at me in confusion.

“What are the pages you're holding?” he asked me curiously. I showed him the pamphlet. He looked at them with great vigilance, sat down next to me and started investigating me: Who am I? In which yeshive did I study? How did the pages come to me? Our conversation turned to yeshive life in Poland and their ways of learning, to famous personalities in Polish and Lithuanian yeshives, and so on. I was surprised to see in front of me a well-read scholar, who recognized the subtle differences between the yeshives of Poland and Lithuania and was well versed in them as if he felt at home. His face and rough clothes did not indicate at all that he belonged to the class of scholars.

Before parting with me he asked about the state of my illness and solemnly assured me that he would take interest in my fate, and later that day he returned and approached me accompanied by the doctor. He gave the doctor a package full of medicines and injections and said: “These are intended for this friend of mine, and I ask you to keep an eye on him”. From then on, my condition changed for the better and there was a great improvement in my condition. The doctor and the nurse visited me often, I received various injections and medicines.

The doctor once explained this thing to me. He told me that this guy, by virtue of his role in burying the dead, visits at any time, freely, the nearest town, and there he buys the medicinal drugs.

As a result of this special treatment, my condition improved day by day, until I got up on my feet. On the day I left the hospital hut, the head of the “gravediggers” came to bless me and introduced himself to me – the former head of the Beit Yosef Yeshive in the city of Ostrowiec, in the state of Poland.

|

|

by Yosef Perlshteyn, Israel

Translated by Tina Lunson

|

|

|

He who has seen a crematorium with his own eyes, Has long, long understood the sounds. And I, although not in the oven myself, Have taken in the horrifying story of the fire.

The crematory fire burns and hisses,

A carcass– o heavens – only skin and bones, |

[Page 421]

|

Of a curse not delivered, or even a prayer, From fear his hair has gone straight. He probably suffered all his lived years, And strove towards a proper grave among Jews, But dying by fire surely not thought of, And that on Yon-kiper – never meant to be!

After him a skeletal woman, her eyes running

A Jewish woman skeleton – a grandmother it seems.

Now here “comes” a young man – a blooming rose,

After him “goes” a girl, or engaged bride even,

An infant child – just suffocated in the gas,

After them comes a body with a torn cross, |

[Page 422]

|

And blazing and scorching in flaming pleas, and it flares and it broils, and it sobs and sizzles, and hisses and stews, stews and gasps: Hiss-ha! Gasp-ha! Ha-ha! Ha-ha!

The air all round has a human-stink |

|

|

[Page 423]

by Rachel Auerbach, Israel

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

Edited by Tina Lunson

In those days, observant Jews were seeking a relief and refuge in prayer. And even among those who were not devout in religion, they often, in their last hours of life, clung to this age-old custom, and together with all the others said kadish for the elevation of their own souls. Because by then, it was already known to everyone that there would be no more male sons left who would go every day to say kadish for the souls of their fathers and mothers. It was known that there would be left no elder nor young, neither children nor babies.

Some of the survivors tell how Jews were gathered inside the death wagons, before mass executions, and said kadish in public.

And sometimes Jews would recite psalms, or – when they were already sitting in a mourning, sitting on the floors of the freight cars – they would begin by saying “Book of Lamentations” and lament. In the verses of Jeremiah the prophet and the verses of Judah Halevi, just before their own destruction, they would lament about the destruction of Jerusalem. With these lamentations they prepared themselves, they were saying goodbye to everything dear to them, as they set off on their last journey, to death. Even among those to whom the world of Judaism was already almost a stranger, there were a few who knew by heart some kind of a prayer. The others would stand and listen, and like proselytes, they would repeat the verses word for word, in which they asked for an essential point of reference, some kind of a grip on something before their death.

While the former neighbors of my uncle, who lived in the village, took him out of his hiding place and led him away to the Jewish cemetery to be shot dead, he pulled out a small prayer book from his coat pocket and said a prayer all along the way. He no longer wanted to gain even one glance at the view of the village; of the faces of those who led him; of those curious who looked at him as he walked towards death. The pages of the prayerbook were his last refuge in the world, the only refuge.

A young man who escaped from Treblinka told me about something he saw in a hut where those who were preparing to go to the “bath” – the gas chambers – were taking off their clothes. There was a large group of women and children. Among them all, one tall woman stood out, whose head was wrapped in a handkerchief. She was standing in the corner, her face was turned towards the wall, to some hidden “east” she created in her imagination. Behind her stood the crowd of women and like her they also turned their faces to that impure wall of the death hut.

As a cantor on Yom Kipur, as a public emissary of a group of women who were condemned to die, the woman stood on that day of judgment in Treblinka, on the day of the horrors of annihilation. In the melody of a prayer of the Days of Awe and in Yiddish words that came from her heart, she laid out her claims to God:

“Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one!” – she cried comfortingly from her heart: “Lord of the world, you are our one and only father, and we have no father but you. Open your eyes and see our poverty, look at our baseness and accept the cry of our children and babies. Remove from us all sin… so that we may be honored… like our ancestors

[Page 424]

Avraham, Yitskhak and Yakov, and as our mothers Sora, Rivke, Rokhl and Leye… may we be blessed… there… with all our loved ones… Merciful Father in heaven!”

A cry burst from her heart and she fell silent. And the whole hut was shaken for a moment by crying, similar to the crying in the holy Day of Awe in the women's section.

“And for the sake of God” the woman opened again with renewed strength – “for the sake of your holy name in the world – take our revenge, demand our blood from the hands of our tormentors. Let not our sacrifice be in vain! The cry of the torture of our children, everything they did to us – may it be on their heads and on the heads of their descendants! On the sons and the children of the sons! Pursue them with your anger and destroy them! Uproot them, as they do to us! Merciful Father in heaven!”

With these words or something similar to them, the woman cried out her plea. She spread her hands towards heaven and the crowd of women stood behind her and with pale lips whispered every word with her. As in the blessing of the candles, their faces were covered with the palms of their hands, they moved their bodies silently and the tears were dropping down through their fingers as in the blessing of the candles.

And by chance, at that time, those who were taking care of the work of extermination did not look at that corner and did not desecrate it… Little by little, the voice of the women went silent until it was blended into the sound of the rest of the crowd.

And another incident was told to me that happened in Warsaw at the end of the first action days, in September 1942.

One day an old Jew came out. Early in the morning, he emerged from his hiding place and decided that he was done with hiding in hiding places. Wrapped entirely in a white robe and a talis, as on the Day of Awe, while his lips were whispering a prayer, he went out into the street, to receive the fate destined for him. With his white beard, wrapped in white robe, his entire appearance expressed a total whiteness and purity. He walked around in the panic that was on the street for a few moments. One executioner soldier or another passed by and did not harm the Jew, who seemed to no longer belong to this world. Finally, one aimed his weapon at him from a distance and shot him, as if he was afraid to look at the shining and bright face of the Jew wearing white…

Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one!

And one is your destiny, the people of Israel, among all the nations of the world…

|

|

[Page 425]

by K. Neyekh, Israel

Translated by Tina Lunson

After a difficult weeks-long slog on beautiful Russian railroad cars, in dirt, hunger and thirst, we finally arrived in a place of comfort.

I say “place of comfort”. It was not any villa in Crimea on the Black Sea or a palace on “Nevski Prospect” in Leningrad. They threw us into a deep forest in Vologda province, USSR.

It was wintertime. The snow covered the world. Our eyes were pained from the blinding blue-white. The cold burned, cut into our limbs like needles.

In several wooden barracks that that we could barely see out of for the snow, we were quartered in small “cabins” about “four by four”. Close to seventy Jewish families with their wives, children and household goods were packed into the disgusting chambers with their bags and packs. There was no place to sit or even to stand.

The Jewish deportees were from Pultusk, Dlugashodle, Suvalk and other places. From Goworowo, there were five or six families. Besides them there were also some twenty Christian families, deported Polish officers and administrators.

Kamaritse was the name of the exile area in Tatshimske region. In this primeval forest, we were to cut down trees. They were sawed and lugged on wagons to the nearest train station.

The grueling work in Egypt was a game compared to the penal-colony labor in this place. From before dawn until late in the evening, the hungering, suffering people lifted and carried the loads like asses, without rest, without food to satisfy, under the rigorous watch of the N.K.V.D. And in the cold of 55 degrees. Our skin split under the pressure and our feet were swollen like puff-pastries. And all this did not awaken a drop of mercy from the Russian supervisors, the N.K.V.D.

But I am not just describing the bundle of troubles of the deportation camp. I believe that there is enough material for a large book. Here I will only tell the chapter of strength of a Goworowo Jew, Reb Itsele, who had

[Page 426]

the moral devotion to lay tfiln and pray every day, although he knew that it could cost him his life.

The head of that camp was a certain Ivan, an N.K.V.D. officer, an extremely wicked man who had an allergic hatred for the Jewish faith. Nothing bothered him as much as a Jew donning talis and tfiln and praying.

I do not know why it fell to me, that Ivan made me responsible for the whole camp. Perhaps because I was the baker there and I served everyone their fresh roll. Ivan promised me that I should report to him when Jews prayed, in order for him to come and punish them. And he warned me that if ever I kept anything from him, he would take me out of the bakery and send me into the forest.

Yon-kiper came, and kol-nidrey. I wrapped myself in my talis and buried myself in a corner. I would certainly not want Ivan to find out that I myself prayed. On the morning of Yon-kiper the few Jews hid in a side room to pray. Ivan sought them but did not find them. He sent me to search. I went off and quickly told everyone to run away. I reported to Ivan that I did not find anyone. Then Ivan encountered a watchmaker from Suvalk, whom he saw was carrying a prayer book around. He gritted his teeth, but he could do nothing to him – he had not caught him in the act.

Then once Ivan chanced to notice Itsele standing in talis and tfiln, praying. Raging blood pounded in his head. He ripped the talis and tfiln off him and attacked him like a thief, screaming and ranting. “One more time”, he warned him, “I will see you begging in the street, you will never get out of prison.”

We begged Reb Itsele to have mercy on himself and not to pray in talis and tfiln, because the murderer already had his eye on him. It was a death threat. Reb Itsele smiled and did not answer. In the morning, he again did what was his right, prayed in talis and tfiln if nothing had happened.

Ivan made good on his threat. He found Reb Itsele praying again, he immediately arrested him and sent him to the Tatshimske prison.

Reb Itsele could not tolerate the conditions in the prison. He got sick there and died.

For all of us it was clear that Reb Itsele had made an accounting of his deeds and he clearly knew that by praying in talis and tfiln he put his life in danger. He was, however, prepared to go as a martyr in God's name.

Certainly, such a case of heroic strength should be noted in Jewish history.

[Page 427]

by Mordkhe Govartshik, Israel

Translated by Tina Lunson

It turned out that I was in Goworowo three times after the war, and each time I went around as if in a cemetery. I could not make peace with the idea that there were no more Jews in the town.

The first time I was in Goworowo in 1947, along with Khayim Shmelts and Tuvye Bielik. It was a visit for personal purposes. The town was not recognizable. On every street stood several new houses on provisional foundations, built by Christians. That time I found the town in the following condition:

On Gedalye Grinberg's place and several places near it were built, provisionally of wood, the “Powshechna” school. The janitor was still the same one from before the war, Rorat. On Rozene's place was the township office. A little further on, on Shafran's place, there was a little shop. Across from that, on Verman, Shikora's place, Stefan Vaytotski had made a business of hog products. After that, Tseglenski had built back his bakery. On Shaul Potash's place, another shop. On Ratenski's place one of his former employees had made a meat business. Khana Fridman's masonry house had only been half burned and the younger Rorat had repaired it and opened a hair-styling institute there (see the photo on page 52). A little further on, Sobotka the “mayor” had established and shop and a restaurant. The priest's palace, the church and the whole “Probostva” remained untouched. The fire did not come here. Khayim Potash's shop was being run by a certain Yozefa from Bank lane. The small mill of the Krulevitshes and Dronzd was specially lit afire and burned by the Germans. The larger mill of the brothers Rits was moved over to Bobovska's place on the “Broad” street, apparently after the Germans. Dr. Glinka lived in his house above, and under that was the ”pasterunek”, the police station. Voytotski had built a business on Gerlits's place. Ratenski had built back his manufacturing business, but on a smaller scale. The place of the study-house was still fenced in with barbed wire then. The bricks from the building had been taken earlier by the

[Page 428]

Christians, who used them for their own houses. Where Yoelke's bakery had been there was another bakery belonging to a Christian. On Menashe Holtsman's place a Christian had made a shop. And on Gurki's place there already stood a little house. A gentile from Yavores had already begun building on the Rov's place and that of Kosovski-Rozen. When I told him that the proprietors were still alive, he ran away. On the corner place of Gemora and Vishnia a goy from Yavores had built a restaurant. A Christian from Sukhtshits had bought the place near it and set up a shop there. On the Bank lane, on Mordkhe Alek's place, one of Voytshik's sisters had put up a little house. Here and there, were a few other houses.

The cemetery was totally destroyed. (See photo on page 23.) The sole sign was the watchman's hut, which stood there as a remembrance.

The princely estates around Goworowo had been confiscated by the Polish government. Glinka's son Stanislav had become a registered manager for an estate in the Wroclaw area. All the villages around Goworowo remained untouched and did not suffer from the war. Thursday remained, as usual, the market day. The grain from the peasants was bought by cooperatives. The goyim took the produce to Warsaw. As a rule, all the commerce lay in Christian hands. But it was not the market day from before the war, with the Jewish merchants and craftsmen, with the shopkeepers and traders who brought life to the trading, initiative, and who were also good customers. Then, the peasant was also happy because he received earnings for his work, and with that money he could buy whatever he wanted.

I was also in Pasheki. The station-master was still the same Yagella. But everything was dead. Now there were no Jewish expeditors, or the wagons full of grain and wood, that used to pass through every week on their way to Warsaw. And where were the wagons of coal, cement and other materials that used to arrive here for Goworowo, Ruzshan and other places around here?

A depression lay over the Christian population. It was hard for them to adapt to the new regime. They were afraid for the future. Also, the peasants lived in fear that their land would be nationalized, and a “kolkhoz” collective would be instituted. The entire management was in the hands of the young Communists and workers.

I was in Goworowo again in 1948 and 1949. During that time another few Jews had sold their places there, but no great changes came about in the persona of the town. Here and there new houses were built, there were some goyishe craftsmen, but the ruin was still vividly evident.

I wander over the “streets” and sad thoughts come into

[Page 429]

my mind. I recall the bristling life of our purely-Jewish shtetl, with the organizations and political parties, with the institutions and little prayer-houses, with the merchants and tradesmen, fine Jews and laborers, and the fermenting youth, who were so bestially murdered by the Hitleristic hoards. I can still not abandon the thought that the shtetl where I was born and educated now remains without Jews forever.

Received by B. K.

by Rov Meyshe Bernshteyn, Israel

Translated by Tina Lunson

Hebrew translated and annotated by Jerrold Landau

|

|

The great Jewish prophet, the novi Yermiahu, who lived through the destruction of the First Temple, received from heaven the divine mission to lament that Jewish calamity. He composed the mournful scroll, “How lonely sits the city, that once was full of people has become like a widow”. [Lamentations 1:1]. He spattered it with fiery lava. He found words to depict the catastrophe, the scope of the destruction; he found the appropriate curses for the gentile criminals; and in the end he still sought in his arsenal of language for a few words of comfort for the tormented Jewish people.

We stand here today and think, what would Yermiahu the prophet say if he had experienced our calamity? Would he find the thunderous, flaming words to characterize even one tenth of the catastrophe? “Would it be that my head were water, and my eyes a source of tears, that I might weep day and night for the slain of the daughter of my people!” [Jeremiah 8:23[1]] is absolutely not enough to lament six million martyrs who were killed by such barbaric tortures that Ashmoday[2] himself did not even think of.

[Page 430]

Could one mine out, from all the 70 languages of the world, such curses that would even a little ease the feelings of revenge against the Nazi persecutors? And are there any such words of consolation that could comfort such a grieving people?

The great poet Rebi Yehuda Haleyvi also lived in a tragic epoch. The huge troubles that were let loose on the heads of the Jews in Spain, touched his sensitive heart and opened the muse of heavenly poetry. He mourned for the Second Destruction and created the elegy “Sha'ali Tsion”, which one recites along with the dirges for Tishe B'ov, with the finale “Lament oh Zion and her cities, like a woman in her birth pangs, and like a maiden enwrapped in sackcloth for the husband of her youth.”[3]

For our contemporary catastrophe the words are too pale. Can “like a woman in her birth pangs” be compared to the crematoria? Is “like a maiden enwrapped in sackcloth for the husband of her youth” a parable for Auschwitz, Dachau and Treblinka? Both the husband and the maiden in her youth were incinerated in the crematoria, along with their fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters together. There is much doubt, whether even that great, godly poet would have been able to gather the fitting words to depict the tragedy of our generation.

The national poet Khayim Nakhman Bialek experienced the horrifying pogroms in Ukraine and Russia. He wrote the “Megilas puranios” [Scroll of Tribulations] and mourned the Jewish tragedy. He shed a tear for Jewish troubles.

If he lived today, his tears would be turned into blood. He would break his pen and refuse to be a poet for Jews. For, how could one, with a human pen, express such inhuman murders and bestiality?

For our tragedy there is only one expression in the Torah. At the end of the “reproofs” in parsha ki-savo it is written, “the Lord will bring upon you all the other diseases and plagues that are not mentioned in this book of teaching”. One cannot describe this. The Midrash on this says, “When they heard the one hundred minus two [i.e. 98) curses, their faces immediately became pale”. The commentators ask, why does the Commentary ask, “Why does it say ‘one hundred curses minus two, and not ninety-eight curses’ as people usually count?”. The commentators answer, that the “minus two” refers to the two terrible curses of “all the other diseases and plagues that are not mentioned in this book of teaching”. If such curses exist, that the holy Torah itself has not found any suitable expression for them – it is a terrible thing for us. “Their faces became pale.” “The faces of those who heard the unspoken curses turned green and yellow on account of that for which the Torah found no expression – that is the greatest expression of our huge tragedy.

However great our tragedy, so great must our comfort be. Our most urgent request to the Master of the Universe is that He may transform the “hundred curses” into “hundred blessings”. He should send down an abundance of so much good, even more

[Page 431]

than He promised us in His holy Torah. It should reinforce the strength of the Jewish land, and a spirit of uplift should be sent down from heaven for the Jewish people.

But with only our comfort the tragedy is still not exhausted. We are still somehow guilty to the victims too: They were murdered as martyrs in sanctification of the Divine Name, not just for us but for the entire Jewish people. The Jewish homeland was established on their tormented souls. What must we do to eternalize and sanctify the memory of them?

When a father or a mother heaven forbid, dies, the children, the orphans, rise up and say “Yisgadol v'yiskadeysh shemey rabo”. In essence the Master of the Universe has taken away the dearest that they had. A misfortune has befallen them. Instead of complaints for the Creator of the World, they go to praise and extol His name.

The truth is that the children feel the suspicion. But they consider the kadish as a sacred obligation over the fresh graves of their dear father and mother, who served the Master of the Universe with every fiber of their souls; and they promise that they will follow in the paths of their parents. With the death of a father or a mother there is a void in the Jewish world. A soldier in the divine army has fallen. It diminishes the power of the Creator, so to speak. A trusted servant is missing, who would extol and praise Him. In that, really, the innocent faith of our parents was very large. A father's prayer, an afternoon and evening prayer service. The Mama's reading out the Tsene-u'rene. The night after Shabes, when she closes her kosher eyes and whispers her quiet prayer “Got fun Avrom, the holy Shabes is going away, and the good week is coming to us, for us and for the entire Jewish folk”. Such pure faith is not to be found in any other nation or language. Now come the children, the orphans, who promise that they will fill in the hollow place that has become empty with the death of their parents: “Yisgadel v'yiskadeysh shemey rabo…”: May God's name be extoled and sanctified by His surviving children.

Let us now present what kind of gaps there are in the Jewish people after the horrifying death of six million fathers, mothers, children, brothers and sisters, scholars, cabalists, scientists, merchants and laborers. How small God's world has become.

Therefore our oath must be holy: “Yisgadel v'yiskadeysh shemey rabo”. We, the survivors, the saved remnant, will fill the large rupture in the body of the Jewish people. We will build back the ruins in a physical sense, and we will lift up the eternal Jewish spirit before the whole world, and we will cry out, affirming in public, “Yisgadel v'yiskadeysh shemey rabo!”

Translator's notes

Composer: A. Y. Brukhanski

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Goworowo, Poland

Goworowo, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Jan 2025 by JH