|

|

|

[Page 95]

by A. M.[1]

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

These pages of the Yizkor Book will be called “The Persons of Note Section”. Many were the colorful figures, very diverse, with many different characters. Even though one individual might be irate at times, and one at peace, each was a precious stone and they all wanted to live a blessed life on Earth.

Sometimes at night when sleep escapes me and passing thoughts float and awaken memories, a long row of living characters, flesh and blood, pass before my eyes.

Quite a number of years have passed by since the destruction of the Jewish communities of the Diaspora. A few survivors of the massacre managed to escape from the valley of death. The old cemetery is long since overgrown with weeds. The mass grave is bare, and no victim can be identified. Perhaps the plough has already furrowed the land. And perhaps someone still wanders around at night, burrowing in the ground, scrounging about in the fertile soil, in his desire to find at least, the hidden jaw of one Jew, where one gold tooth still remains as a remnant.

And now, after years have gone by and life is taking its course, Jewish people here and there, are involved in reviving memories of the past. Jews still sit today engaged in writing pages of Yizkor[2] about the destruction of small towns and communities that were annihilated.

And you, a Jew from Steibtz, when you open the pages of the book in front of you, your eyes will certainly scan and search for the descriptions and images in memory of your townsfolk who once lived and are now, no more. You will be overcome by nostalgia in your desire to refresh your memory and awaken a description from the life of your father, mother, neighbor, companion, friend, street, market, synagogue, school, and political center. Your soul will certainly long to behold the image of the people who labored and toiled on this land from generation to generation.

Footnotes:

by Dr. Yisrael Machtey

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

(In memory of my grandfather, Rabbi Eliyahu son of Yosef, ritual slaughterer and meat inspector– May the memory of the righteous be for a blessing! (2 Tishrei 5609/1849 – 11 Elul 5698/ 1938)

“ … like the likeness of the rainbow amid the cloud:

Like a rose placed in a lovely garden:

Like the purity of the turban placed on the turban pure:

Like the one who sat in concealment, pleading before the King:

was the appearance of the High Priest.”[2]

From earliest times and onward the residents of our small town related to the days of the month of Elul[3] with respect and seriousness: the Days of Awe are coming into actuality and are drawing near. The sound of the shofar[4] was heard and we would get up early in the morning (yes, often the children too!) to recite Slichot[5]. Majesty and mystery surrounded these prayers which were said before dawn. My grandfather would get up early, but I, who was attached to him, tried not to lag behind him and take part in the service. When I was still a child, my grandfather served as the shofar blower in the new synagogue and during the month of Elul he would practice on various shofars to produce clear and beautiful sounds.

My grandfather, Rabbi Eliyahu, was born on the second day of Rosh HaShana[6] in the year 5609/1848 in Steibtz, where he grew up, was active and died at the ripe old age of 90. In his moving article in the Dvar[7] yearbook of 5712/ 1952, Zalman Shazar[8] writes that my grandfather was not only a ritual slaughterer and meat inspector and chief circumciser, but also a Torah reader in the synagogue, shofar blower and prayer leader. In addition, he was a matchmaker for lucky couples and matchmaker for the rabbinate, stone cutter for gravestones and a rabbi on behalf of our small town. I hardly saw him working in these “professions”, for in my time he no longer cut stones for gravestone monuments and no longer served as prayer leader (except on days when he had a yahrzeit[9]) and he seldom served as a public Torah reader. For the rest he served until the day he died, mainly in ritual slaughtering and circumcision, although the latter did not provide him with a source of livelihood.

The Jewish New Year was a double holiday for us: the day the world was created and my grandfather's birthday. When he returned from the synagogue on the eve of the holiday, the red watermelon (a rare delicacy for us), the honey and the challos[10] for the kiddush[11] were already awaiting us on the table, and the blessing “for a good and sweet year” had a double meaning: wishes for a happy New Year and wishes and blessings for the head of the family.

On those days when my grandfather also served as shofar blower, the Jewish New Year was for us not only the day when the world was created, but also the day when the ram's horn was sounded. We would proudly watch my grandfather ascend to the bimah[12], wrap himself in his prayer shawl, in preparation

[Page 96]

|

|

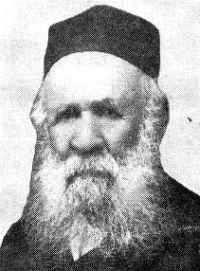

| Rabbi Eliyahu, ritual slaughterer and meat inspector – May his memory be for a blessing! |

for Lamenatzeach[13], and with some trepidation and holding our breath, we would wait for the following: Would he be successful? Would the shofar's sound be distorted? Would lovely and clear sounds come forth? And would the tekiah gedolah[14] be really long? Would it reach the heights of the Heavens, to the footstool of the Creator of the World? And while he was standing there on the bimah, this man of short stature became head and shoulders above all people, as one who pleads before the Creator. Like the High Priest on his shift, his appearance was “like the image of a rainbow amid the cloud”. The tekiah–shevarim–truah[15] would cry out to G-d on High and break open hearts and souls. And suddenly he lowered the sound! For a moment our hearts were besieged by fear: Did he fail? Of course not! It was a short delay, understandable for his age and once again the polished sounds quickly burst forth and the stone was rolled off our hearts.

The Eve of the Day of Atonement was not like it is now. It was the most awesome day, even more awesome than the Day of Atonement itself. From the afternoon, you felt in the street that the Day of Atonement had indeed come. In the street in more senses than one: for Jews and Christians alike. Nullification of Vows in the morning, “kapporos”[16] with the mysterious words: “Children of man, who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death”, words which we didn't understand as pupils, but from which the odor of death reeked. The exceptional afternoon service in which there was “For the sins we have sinned” in the 18 Benedictions of the daily prayer. In the rear of the synagogue, alongside long tables, emissaries of mitzvos[17] were seated with bowls for collecting money for providing for a poor bride and for acts of charity and other things, and I, too, helped with the “propaganda” for contributions. Sometimes new worshippers came in, those who arrived late for the afternoon service with the congregation, which didn't prevent them from beginning to pray the 18 Benedictions prayer aloud[18] in order to make us stand up for the kedusha[19].

The last meal before the Fast is finished. The candles are burning. We drink our last glass of tea and we children approach Grandfather, wearing a kittel[20], for the traditional blessing. Evening falls slowly. Silence reigns in the street, and only our steps are heard in the street and even these steps are not heard, since most of us are wearing overshoes or rubber shoes. Everyone turns into the synagogue and at that moment the verse engraved upon the doorpost of the main gate, “For My House will be called a House of Prayer for all people”[21] takes on a deeper significance… Tefilla Zaka[22], after which Grandfather and the notables of the congregation, holding the Torah scrolls, surround the cantor as he recites Kol Nidrei[23]. He is 'wrapped in the majesty of our ancestors as he stands thus, “like the purity that was placed on the turban pure”.

Grandfather was exempt from inserting a peg for the “sukka”[24] at the conclusion of the Holy Day, for, as far as I recall, we had a permanent sukka, but inserting a pole for the opening of the roof and arranging the schach[25] – that was his job and we gladly helped him in that task.

Pomp and circumstance were his lot on the Festival and on the Intermediate Days. He dressed modestly and with unpretentiousness on weekdays. He was very shy and retiring, moderate, loving people and forgiving of his few opponents. He was a somber person who didn't look somber, but still you could see it. And he wasn't heard, but still you could hear him. It seems to me that the question which, I think Idel Tunik, one of the town elders, addressed to him characterizes his temperament: “Rabbi Eli, have you ever gotten angry in your lifetime?” When I was small, I indeed believed that my grandfather was one of the “36 Righteous Men”[26] and that he would live forever.

I don't remember his many dear friends. Simply, he was the oldest of them all. (The only one who was older than him and whom I remember was Yona Rubin, who died at the beginning of the 30's at the age, according to what people say, of 105 or more.) One of the few he was closest to and whom I remember was the rabbi of the new synagogue, Rabbi Moshe Neifeld. In my opinion, my grandfather's decline and slowing down started from the time of Rabbi Neifeld's death in the mid 30's.

He served as a circumciser with a quick and sure hand until his last days, and he practiced this profession not as a way of earning a livelihood but only for the sake of performing a commandment. By the way, I don't recall my grandfather ever resorting to deceitfulness in any matter. With regard to one instance of “deceitfulness”, he used to recount the following: This occurred around 1906. His son, my Uncle Aharon, was then studying the art of circumcision and my grandfather wanted to set him up to “work”. Naturally, it was not an easy thing to bring a new circumciser into the small town, and the first father of the baby undergoing circumcision (incidentally, he didn't know my grandfather) refused categorically to allow anyone to “practice” on his son. Therefore, my grandfather gave orders not to reveal to the father of the baby undergoing circumcision who the apprentice was, as it were, and who the circumciser was. And so it was: My uncle circumcised the baby under my grandfather's supervision to the satisfaction of both sides.

He was old and his old age enchanted us. We loved to listen to his stories of days gone by, and he had various amusing stories to tell, most of which, however, were serious and mysterious such as the story about an old man who suddenly heard a voice calling him to the synagogue: when he got there, he was called by the voice without a body to go up to the Torah. He went up, recited the blessing and then went down and died a short time later. Or, for example, the story that led to the cancellation of the permanent death–bed that was in the cold synagogue. And this was the story: Moshe Aginsky (Baba Baskin's grandfather), who was on his way to pray in the synagogue in the morning twilight, suddenly saw a white form jumping down from the “bed”. The explanation that this was a white goat which had found its night's rest in the “bed” was to no avail. The man got scared, fell ill and died shortly after and, from that time on, they would make every deceased person a “bed” of his own. And, it seems to me, that with the death of the chief of the fire fighters in Steibtz, Reb Shmuel Tunik, a permanent “bed” was reintroduced.

The Chanukah candles flickered like golden stars there in the old house. By the way, the beginning of winter was accompanied by a special ceremony: putting in double windows, filling a layer of insulation between the two windows with glasses to absorb the moisture and gluing it with paper dampened with milk. Despite the large space that both windows occupied, there was still enough room on the windowsill for a menorah[27]. For the most part, a Chanukah menorah here is very simple. The main thing, of course, is the candles, the “dreidel”[28],

[Page 97]

giving gifts of Chanukah money and, of course, potato pancakes smeared with goose fat. The geese were fattened especially for the coming winter. When Grandfather recited the blessings over the candles and the miracles, and when he would recite the Shehecheyanu[29] blessing (and he could also add from the 18 Benedictions prayer: “for the salvation and for the mighty deeds and for the redemptions”), the mischievous flames of the candles winked at us and turned into miniature fireworks. One day led to another, and candles come after candles: one, two, five, seven, eight, and when the last candles died out, suddenly something seemed to be missing at the double window, and the winter night seemed darker and more foreboding…. although the church bells rang out joyfully in advance of the new civil year. With joy and happiness, the sleds slid along to the ringing of the horses' bells: going to “meet” the new year. Not only Christians but quite a few Jews as well celebrated this event: the period of balls and the carnival.

This was already no longer my grandfather's world. As soon as the Chanukah candles went out, the month of Tevet came to the world. The Fast of the 10th of Tevet approached, a reminder of the beginning of the destruction of the First and Second Temples.

The days of the months of Shvat and Adar – special commandments on their behalf: preparation of wines for Passover (in which my Uncle Aharon was mostly engaged) and the baking of matzos[30]. How happy we were to stay in the bakery and to see how a matza is made from start to finish. The wrapped matzos were put in a box and placed on the baking oven so they wouldn't get wet[31]. A special chapter of laws for matzos was the preparation of matza–meal[32] and small pieces of matza were crushed using a large wooden mortar, very hard work which has since passed from this world.

|

|

|

|

| Rabbi Eliyahu and his son, Aharon Machtey |

And so we reached the great day: the Eve of the Passover Festival. On that day I had special rights: In the morning, my grandfather would complete a certain tractate of the Gemara with me, as I was a first–born son. After that, we would go to the town bath house for the ritual cleansing of utensils and the burning of a large wooden spoon in which there was leavened food – breadcrumbs gathered the evening before.

The night of the Passover seder[33] was the loveliest, most beloved and most festive of all the holidays. Grandfather would become a king, sitting at the head of the table dressed in his kittel with the men – his sons and grandsons – to his left and the women to his right. The Haggadah[34] was not just the retelling of events connected with Passover. We were allowed to stop reading in the middle in order to ask questions, make a sharp remark or an interpretation, and it made no difference if we repeated nearly the same things every year: we always waited for them and they always seemed new to us like the new utensils and the new clothes and the renewing Festival of Spring.

We all used to recite the blessing of sanctification over the wine – all the men, even we children, made a blessing over the wine from the time we reached the age of performing mitzvos. On the other hand, we were not eager (at any rate, I wasn't) to “steal” the afikomen[35]. It seemed to me that this thing detracted from the festivity. We recited the Haggadah in unison, and the reading was accompanied by cheerful melodies such as “And it came to pass at midnight” and the like. And here I have to reveal a secret which I was afraid to tell: the “secret” is related to the song Chad Gadya[36]. When we would get to the words “and the Angel of Death came and slew the slaughterer”, I would secretly look at my grandfather's face to see his reaction, and I would try to get through this part quickly – I was simply afraid.

My grandfather had a special claim in the new synagogue: he would insist on counting the Omer , and the congregation would repeat the counting after him. It seems to me that this was the only instance in which he willfully stood out in the synagogue. Normally, he was a very modest person. It was customary, for example, that if the rabbi was not in the synagogue, the prayer leader would wait before repeating the 18 Benedictions prayer until my grandfather finished his own 18 Benedictions prayer, which took him a long time to complete, On weekdays, in order not keep the congregation waiting, my grandfather would withdraw to the side of the synagogue behind the pulpit to recite his 18 Benedictions prayer, and by doing so would free the prayer leader from waiting for him to finish.

[Page 98]

The counting of the Omer[37] in the year 5698/ 1938 was the counting of my grandfather's life. At that period of time, Leib Baruchanski, the second to my grandfather according to his age, and two years younger than him, passed away. This affected him to the depth of his soul. Instead of his scoffing–optimistic saying: “People comprise a group that is bound to die, but I don't belong to that group”, this time he said, “Now I see that there is not everlastingness.”, as if he saw his own end drawing near.

From that time on, his condition worsened. Cancer began to gnaw at his body. Nevertheless, he didn't stop his usual life routine at home, in ritual slaughtering and in circumcision. While working in his yard repairing the fence, he was called to perform a circumcision. He went there without delay and circumcised the baby. At the very moment he finished that holy work of fulfilling a commandment, he felt ill. He was taken home and three days later on the 11th of Elul, 5698 [September 7, 1938], he returned his pure soul to his Creator, about two weeks before his 90th birthday.

The funeral was the biggest of funerals which I remember and his grave was dug next to his friend, Rabbi Moshe Neifeld.

Translator's Footnotes

by Menachem Halevi

Translated by Ann Belinsky

Words at the opening of the library in his name on 17th September 1953)

With awe and reverence, I raise the image of my father-in-law, of blessed memory – the most honorable of men, who elevated himself from the midst of his people by his own strength, and when amongst his people, he rose above and inspired every person who came into contact with him.

“The Teacher” – this is who he was, and the term of endearment remained. In his town, he carried on his shoulders,

|

|

| Alter Yosselevitz |

all the concerns for the Land of Israel. Like the toil of ants, gathering crumb by crumb, he gathered and educated student by student, until he transformed most of the small town that, until his arrival, was far removed from Hebrew and Zionism, into a huge Hebrew camp. We found in Tosefta[2]: “greater than the sages – is his name”. And for those who called him “The Teacher”- even his name was superfluous.

We are here at the modest ceremony, at the opening of a library in his name. At times, I saw him handing out books to readers – in the only Hebrew library that existed in his school, that was established mainly with his meagre savings (i.e. and his many debts . . .) – I often saw him advising a reader on what book to select, and if this was a past student of his – he would “test” him with a greater expression of empathy, on everything. Of course, with his many public dealings in the town, he could have given the role of librarian to someone else, but he rarely did this. He had to feel the Hebrew pulse that he established with his own hands, in the Hebrew town.

He was a general Zionist – to distinguish from the “General Zionist” political party. For him the term “General Zionist” referred to the individual, who was a Zionist in all his being, Zionism without affiliation, Zionism “with all your soul and with all your might”[3]. This was constructive Zionism, a love of Israel, above politics.

He did not own a house, but whoever saw him pass by a building that was being erected, could recognize the constructive details in his soul – he would linger over every aspect: if the bricks were not sufficiently burnt, if the carpentry was not perfect enough. He suddenly became an expert on painting, as if the house actually belonged to him. At times, when I saw him standing like this, alongside a house that was being built, I felt that he was building the Jewish nation, building the Land of Israel in his imagination.

Many of the residents of his town differed in their opinion to his view of Zionism, especially among the Leftists. I do not know how many of these whom Providence left alive, fulfilled what they preached to him in the town. Of one thing I am sure: if my father-in-law was with us now, although he was not one of those who mumbled the words of the Rabbis, - he would understand and physically affirm, that the State could not be built without a change in values, without positioning an economic and cultural pyramid, a heritage of the exile, on a firm base. Because his Zionism was such a vital part of his life, he was even willing to become a socialist – and put it into practice . . . .

And he was not only Der Lehrer - “The Teacher”; he was a helpful teacher, a true teacher: his home was open to all kinds of people, of all types and classes – from the simple tailor to the daughter of a rich man. All came to ask his counsel, came to speak of their troubled souls. He was an 'institution' in the small town.

[Page 99]

|

|

| The Opening Ceremony of the Library[4] |

The master of the prophets[5], when he stood on Mount Abarim[6], wept and pleaded to be permitted to enter the heathen Land of Israel, and when the teacher Alter stood on the threshold of the Covenant Between the Pieces[7], rejected his children's request to come to the Hebrew Land of Israel, two or three times, for “to whom can I leave the small town, the school” – he wrote.

The man who elevated himself by his own strength and inspired all who came into contact with him – did not want to make Aliyah[8], he felt that he was unable to leave; but with all the House of Israel, with the martyrs in Europe, - he ascended . . . In a small note that miraculously reached us during the days of the occupation, he wrote: “My place is here among the people of my small town. Their fate – is my fate. Farewell”.

This modest library will be used – alongside the modest projects that his students, his children and grandchildren have established by being in Israel, and the fact that buildings are being erected in different settlements – this seal will be stamped into every book – a modest memory to a modest man, a descendant of the “Children of Moses”, in a world that was, and is no longer.

Translator's Footnotes

by Moshe Bar' Natan Akun

Translated by Ann Belinsky

Unfortunately I left my beloved town of Steibtz in 1897 at the age of 14. But I can still reminisce and recall those people of Steibtz, of blessed memory, whom many of the Holocaust survivors do not remember.

I always thought that the artisans were simple Jews, knowing at the most to read the Psalms between Mincha[1] and Maariv[2] and no more. I discovered I was mistaken. For example: A tailor named Mishka der Schneider, of blessed memory, lived in Yordzika Street. They called him Mishka der Rav. He studied laws of the Shulchan Arukh[3] every day before the minyan[4] of people in the Great Synagogue and explained them in good taste. I loved being with him and hearing his explanations of religion and law. Who from the people of Steibtz does not remember R' Yedidia der Shuster[5] of blessed memory, who they would always call by the name Rabbi Yochanan Sandlar behind his back? He studied Gemara[6] and Mishnayot[7] together with two more people, one of them my father R' Natan of blessed memory, and the other R' Yitzak Shmuel Epshtein of blessed memory, and, as the Rabbi the Gaon R' Shlomo Mordechai Brodny of blessed memory told me, they excelled in their studies.

Next to my parents' house there was the shop of another great scholar, a performer of good deeds, who lived in modesty, R' Moshe Melamed. Even in his shop he spent day and night “on Torah study and on service to G-d”. At the head of the first row in the synagogue sat R' Yisrael-Issar Eizenberg of blessed memory, and together with his sons Yosef and Chaim, we studied Masechet Nezikin[8] and although he was a great scholar he did not make a livelihood from the Torah, but dealt in selling beer. Every morning after prayers he studied the Talmud[9] until 11a.m. We studied with the Dayan[10] of Steibtz, Rabbi R' Yehoshua Midivitzky of blessed memory who moved to Baranovich, and at the age of seventy made aliyah[11] to Jerusalem where he died in 5695 (1934). Amongst us there was one pupil called Haim Tzornogovovisky who, at the age of fifteen, was already proficient in Nezikin. And I also remember well Mr. Zalman Rubashov, the President of the State of Israel, of whom all the people of Israel are proud.

Last but not least, I mourn bitterly the death of my dear friend Alter Yossilevicz, whom I knew well and who was a dear teacher who devoted himself to encourage Zionism and instilled Torah learning in young children in Steibtz.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 100]

by Getzel Reiser

Translated by Ann Belinsky

R' Nachum Elihas had an extraordinary personality. “Even a child is known by his deeds”[1] – and when he was of Bar Mitzvah age he already exhibited exceptional wisdom. Over time he become strange to many, a type of hermit and parush (one who leaves his home to study Torah), distancing himself completely from all the “mundane delights”.

R' Nachum'kah became elevated in this personality, and the people of Steibtz knew that he was great in Torah and in his piety, but his ways were hidden.

His life and activity were like a puzzle: he would seclude himself on certain dates, did not trust even of the slaughtering of R'Eliyahu the ritual slaughterer and would himself slaughter a chicken for Shabbat.

His relationship with the community was limited and his meeting with them was only whilst walking to the mikveh (ritual bath) to purify himself for Shabbat.

He slept little, and would study Torah for many hours at night.

He was a quiet person in his nature but in his few discussions with the great Torah scholars in our town, his tremendous knowledge was realized and there was always satisfaction in his administration of justice.

He was a pleasant person and admired by all the townspeople.

In an hour of sorrow or anxiety and on difficult days, many from the town would turn to him to receive advice and a blessing.

Especially at the beginning of the First World War, there was much panic among the townspeople. Many began to seek his statements, as they saw in him a G-d-fearing personage, great in Torah and during the riots they found much encouragement in his words. Many of those enlisting received his blessing.

R' Nachum lived in solitude and poverty. He owned a spare lot in the neighborhood of the Yursidkim and he donated it to the needs of the Talmud Torah.

One of the townspeople says that after the First World War they found him studying Torah in one of the synagogues in Minsk, since then nothing is known of his fate or the story of his life.

May his memory be blessed!

Translator's Footnote

(Yudel the melamed[1] from Derevna)

by Rabbi Moshe Levin, Netanya

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

“And they that are wise shall shine like the brightness of the firmament and they that turn many to righteousness like the stars forever and ever. And they that are wise shall shine like the brightness of the firmament – this applies to a judge who gives a true verdict on true evidence and they that turn many to righteousness – applies to Teachers Of Young Children. Like whom? Rav[2] said: for example, Rav Shmuel bar Sheilat,[3] as it is told that Rav once found Rav Shmuel bar Sheilat standing in a garden. Rav said to him: Have you abandoned your trust and neglected your students? Rav Shmuel bar Sheilat said to him: It has been thirteen years now that I have not seen my garden, and even now my thoughts are on the children.” (Gemara: Tractate Bava Batra 8b[4])

Great and decisive is the mission of the judge in the life of the people. The fate of the people is placed in the hands of the judge with regards to their money and body, honor and soul, and he judges them for good or for evil. And so, it is obvious that in order to fulfill this very responsible mission with trust, the personality of the judge is what determines the extent of the responsibility. And not in vain our Sages enumerated the qualities of the person who sits in judgment: wisdom, understanding, G-d–fearing, hating money and love of mankind.

And behold! How much toil must a person exert to earn one of these qualities and, all the more so, to acquire them all? Our Sages asked: Who, for example, is a person entirely perfect in qualities? And they answered: Those who turn many to righteousness are teachers of young children.

Rav gives us the answer to our amazement by citing the case of Rabbi Shmuel ben Shilat's “Ginata” [garden]. The judge, despite his difficult and very responsible role, does not have to give up his personal and spiritual world. He is free to stand on his own inside his special “Ginata” to keep his independence and, together with this, to fulfill his holy mission. Our Sages of blessed memory defined it nicely and said: Any judge who comes to a decision of truth – even in one hour– becomes the partner of the Holy One Blessed Be He in the Creation of the World.

This is not so with regard to those who turn many to righteousness – the teachers of young children. In order to sow seeds of the first light on the furrows of the hearts of small children, there must be powerful and unlimited love and boundless devotion. Only then he will be able to see that the seed sown is bearing fruit. This tremendous power was discovered only in Rabbi Shmuel ben Shilath and his friends who, for 13 years, did not see his “Ginata,” he diverted his attention from all his personal assets and penetrated into the world of his young pupils. Only an outstanding educator like him the text compared to stars that shine forever and ever. Although a star looks small to the eye that sees it, it is big in its world, and if it were not so, we would not merit any ray of its light. Like the case of the stars in the sky, so are the stars on the earth, and they are the teachers of young children.

One of the elite and outstanding people in the field of education was my father, Rabbi Yisrael Yehudah Ha–Levi Kapushchevski z”l, May Hashem avenge his blood. His lessons and his instructions in Torah, Prophets, grammar and the rest of the subjects were outstanding in their great clarity. The light he lit in the heart of his many pupils illuminated their way for all the days of their lives.

My honored father z”l was born in the village of Ratzmila, which is located between the small towns of Lyubcha, Selub and Navaredok, to his father Rabbi Yaakov Kapushchevski and his mother Feige, whose ancestors, and forefathers, had lived in that village for generations. The farmers respected them for their honesty and their good relations with them. His parents earned their living by the fruit of their labor, by marketing the village's produce to the towns and also by supplying various commodities to their village. Although they were “yeshuvniks”[5] by birth, they worked hard and took care of their children's education so that they will be scholars. Their efforts brought excellent results. And from the village house of the “yeshuvnik” the two sons went into the wide world to seek Torah and knowledge. One of them, the eldest son, Rabbi Yosef Ha–Levi Kapushchevski,

[Page 101]

later settled in the town of Lyubcha with his wife Hinde and was accepted there as a Gemara teacher for the local boys and gained a reputation as an expert in the teaching of the Talmud. The second was my father, Rabbi Yisrael Yehudah z”l. They also had a daughter, Mrs. Sarah, who after her marriage immigrated to the United States with her husband Chaim.

My father z”l, and two more young men from Lyubtcha, travelled to the renowned Mir Yeshiva to study with HaGaon Rabbi Chaim Leib, head of the rabbinic college of Mir. The two young men were the Yossilevitz brothers. After leaving Mir, the eldest became rabbi of the town of Suwalki and the second, Alter Yossilevitz, became the principal of “Tarbut” school in Steibtz. My father z”l was 21 when he left Mir Yeshiva after he devoured knowledge in Gemara, Rashi[6] and Tosafot[7], and when he came to Minsk he found the source of the educator's soul which pulsed in him.

His diligence in his studies in Minsk was indefatigable. He read books in Hebrew and foreign languages day and night, and within a short time my father z”l learned Russian and Hebrew well and became an outstanding scholar of the Bible and world literature. When he returned from Minsk, he married our mother z”l, Mina, daughter of Rabbi Itche Meir and Riva Nechah from Lyubtcha.

Under the influence of our grandfather, who owned a bakery and a flour store, my father also opened a store for selling flour and grain. However, he quickly left the store in the hands of my mother, who possessed business acumen so that he could devote himself to his pioneering work in the field of education. His first activity was laying the foundations for the old education with the addition of the achievements of time within the framework of the cheder in the city of Lyubtcha. My father hurried to get ahead of the educators and new reformers whose heart was set on making changes in their way of thinking. In other words: “to clear out the old crops before the new” [Leviticus, 26:10], and to set up the school on the basis of secular subjects alone. My father z”l arose and by himself introduced secular subjects into the curriculum of the cheder based on the idea of “the beauty of Japheth shall be in the tents of Shem”[a combination of world culture with the Jewish Torah]. He taught all the subjects by himself: Hebrew, Russian, math, history, grammar, etc., and by doing so he succeeded to fulfill what was missing in the curriculum of the cheder in those days. The results were positive and justified his experimental action. Most of his pupils, who finished their studies in his cheder, not only that they were not harmed in their religious consciousness, but, on the contrary, these buds and flowers actually strengthened their consciousness and good faith. My father's cheder also served as a corridor for streaming pupils into yeshivos. He practiced what he preached and sent his own three sons to yeshivos in Baronovitz, Radin and Mir.

It wasn't long before my father z”l became famous as an outstanding educator possessing nobility of mind, and as a knowledgeable scholar in command of all general subjects.

The Zionist idea, which then time made waves and struck roots in the small towns of Russia and Poland, and aroused activity in the organization and preparation for Zion – was prominent in the education movement as well. Just as two different streams arose in the Zionist worldview: the secular and religious, two parallel channels were also revealed in the education system in the field of Jewish settlement in the Holy Land, with both having common direction: the education of the generation for a Hebrew cultural life but in separate atmospheres: secular and religious.

My father z”l, felt the order of the hour and immediately recognized the Zionist point in education. With modesty and wisdom, he succeeded in introducing into his cheder the atmosphere of Zion in the spirit of Yisroel Saba[8], and secured for himself an independent position in the educators' camp.

To his great sorrow the distress of the First World War suddenly came upon him and disrupted all his plans, and in these tumultuous days he was forced to take the wandering stick and leave his place which was destroyed by the fire of the battles of war. When the people of Derevna offered him to come to them and stand at the head of the education of the young generation, he acceded to their request and moved there. Also in this new place, despite the frailty of his strength due to his great suffering during the war, he saw great blessing in the area of education, in the continuation of his method and in the establishment of an elementary school, which included secular and religious studies according to all the ingredients of a modern school. After finishing elementary school, nearly most of the pupils went on to yeshivos: some to Radin, some to Mir, some to Grodno, some to Klotzk and Baronovitz. Most of the yeshivos were filled with boys from Derevna, and when they returned home for the holidays, the synagogue in Derevna turned into an actual yeshiva, with a clear majority of the yeshiva boys being former pupils of my father z”l.

His reputation as an outstanding educator, whose heart was alert, and as a fighter in the war for Torah in his old age, reached the ears of the famous Gaon rabbi, R' Yehoshua Lieberman, May Hashem avenge his blood, the Rabbi of Steibtz, and when he founded Talmud Torah school in his town, he invited my father to stand at the head the institution. And here, as fate would have it, when he came to Steibtz to assume the leadership of the institution, my father recognized the head of Tarbut school, his friend from his youth, Alter Yossilevitz z”l, and both of them, sons of the same small town and graduates of Mir Yeshiva, were placed, one against the other in the battle for the character of Jewish education in the city.

In his new place, as in his previous places, he won the hearts of his acquaintances with his humility, devotion to his duty and his wide knowledge. Nothing could have moved him from his tranquility and the pleasantness of his superior qualities.

Regarding Moshe Rabbenu [Moshe our Teacher], it is indicated in the Pentateuch (Numbers, 12:7) “he is faithful throughout My house”. A person wears many faces, transforming himself according to time and place. The appearance of a person in public is surely not the same as a person in the confines of his house and his family circle. Moshe Rabbenu, however, whether standing before kings or before his brothers, was the same person “he is faithful throughout My house”. My father z”l was also an innocent man, there was no disparity between his inner and outer character and he was pure in heart. Even in the bosom of the family, I don't remember him once scolding any of us or, all the more so, raising a hand against any of us.

He had many pupils all over the world who drew knowledge and inspiration from their rabbi's teachings, and remember the pleasantness of his ways with people on whom was drawn a thread of grace and humility.

Also in those gloomy days, when the heavens turned black, on that fateful day, when they severed the wick of his life, he did not stop learning.

Together with our father, our mother, the righteous woman Mrs. Mina, our married sister Sarah Devorah in Derevna with her upright husband, R' Avraham Malin and their children, and our young sister Nechama, May Hashem avenge their blood, were killed by the Nazis, May their names be erased!

My brother, the highly esteemed Rabbi Avraham, who was called “Aromas from Derevna” at Radin Yeshiva, was deported to Russia with the yeshiva, and all traces of him were lost.

These are our family members who, thank G-d, are alive: my eldest sister Chaya, who is married to the erudite Mr. Dov Berger in New York, an educated linguist who serves as a translator for languages and literature, my sister Batya in Poland, and my brother Rabbi Yosef Kapi, who studied at Mir Yeshiva and lives in the United States in the city of Providence, Rhode Island.

Translator's Footnotes

by Shmuel Epstein

Translated by Ann Belinsky

I met the teacher Alter Yossilevitz in Steibtz in 1921. His shining face, moderate and cordial speech brought me close to him as brother to brother. And since then, when I visited Steibtz, I would visit him at his house and at the Tarbut[1] school that he founded and was its headmaster.

In 1923 he came to Baronowitz to a meeting of the “Zionist activists,” when Leib Yaffe, of blessed memory, was in Baronowitz. I saw with my own eyes how he stood erect. I heard his emotional voice when he spoke about Eretz-Yisrael. He spoke with internal passion adorned with vision and hope, with a special charm spread over his face.

In the course of time I would visit my relatives in Steibtz and didn't pass over the house, or the school, of the distinguished teacher and educator, Alter Yossilevitz. He would talk about his school and his pupils with love and dedication. He was pleasant, loved mankind and was loved by mankind. He inserted the Zionist idea in every home in his town, lighted holy flames in the heart of his listeners, admirers and those who honored him. In his light, generations were educated and grew up to become pioneers and self-fulfilled. His house was a meeting place for sages and those seeking his ideas.

He restored a full life to his city that was almost destroyed in the First World War. He was a symbol of kindness and refinement. His eyes always reflected internal peace. Everyone who saw his hearty smile, and everyone who heard his genial and soothing speech, left charmed by the conversation with him.

Our friendship continued for about twenty years. And then, the Second World War broke out. The “Hebrew” descended to the underground. At our last meeting in Baranovitz in 1940, we did not fear to speak Hebrew. Again I saw him tall and pleasant. He told me about his children who were living in Eretz-Yisrael and fulfilling his dream.

The teacher and distinguished educator did not manage to see with his own eyes the independent State of Israel, but his children, may they have a good and long life, Aminadav, Chemda and Avner, are to be found in the first rows of the builders of the Land in Degania and Jerusalem. They are realizing the dream of their esteemed father.

His good name and his memory will not be forgotten by the people from his city and from his admirers, The Steibtz Organization in Israel has commemorated his name for generations. The organization has established a library in Tel Aviv in the name of the teacher and educator, Alter Yossilevitz.

May his memory be blessed!

Translator's Footnote

by Yitzchak Tunik, Advocate

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

In his presence, they called him Rabbi Meir; not in his presence, they called him Meir Der Geller [Meir with the Yellow Beard]. In the mouths of the elders of the generation, he was, Meir Leibe Son of the Scribe, after his father-in-law, Leibe the Scribe, who was also a shamesh[1] in the Great Synagogue for many years.

|

|

| R' Meir Chaitovitz |

R' Meir arrived in Steibtz on foot at the beginning of the 1880's with his boots on his shoulder. He was born in Lubtch on the descent of the Neiman River, and studied in the kloyz[2]. Later, he wandered off to Eishyshok, and when he arrived in Steibtz he ensconced himself in the Great Synagogue, ate his meals on fixed days at the home of various residents and studied Torah, the Six Orders of the Mishna[3], the Gemara and decisions of arbiters of Jewish law. Leibe the Scribe, the shamesh of the synagogue had his eye on him as a groom for his daughter Masha. The shamesh promised to support him, but the allowance ran out quickly and Meir began to be concerned about his family's subsistence by opening a grocery store. He was a great scholar and possessed deep understanding. He didn't like disputation, but was keen and sharp-witted and knew how to delve deeply into a subject, to clarify and explain it. He would elucidate every single matter with logic and good sense. He liked the Maharam Shiff[4] more than all the other commentators and studied his commentaries with great diligence. His store was in the center of the market. A wholesale grocery store filled to overflowing with sacks of flour, salt, barrels of herring, kerosene, sugar and the like, various commodities. His turnover was mainly from retail grocers, and on market days from farmers in the area. He was tall and strong and could lift a sack of flour without any effort. He wore a long coat and a black hat with a peak, under which protruded a skullcap which covered his forehead. His voice was hoarse from perpetual negotiations with customers and from studying Torah aloud. His yellow beard took on a color of old age and, nevertheless, he was spry and active in everything he did, arguing and convincing in logical things which were said with great intelligence. His faith was complete and as solid as a rock. He was never tested by doubts and was never troubled. His way was clear before him – to be a Jew and study Torah, and not just study, but go deeply into the subject and understand it. No prayer excited him as much as the blessing, “With great love,” when he emphasized the words: “and instill in our hearts to understand and elucidate, to listen, learn, teach, safeguard, perform and fulfill… Enlighten our eyes in Your Torah, attach our hearts to Your commandments and unify our hearts to love and fear Your name, etc.”[5] His personality and uniqueness were embodied in these verses – there is no need to add anything more. He wasn't affected by what was going on in the street, nor was he influenced by different opinions and new theories. The Haskalah[6] Movement did not harm him, and he considered it a cult of fools and Germans, who had been caught up by it because they had never tasted the taste

[Page 103]

of a page of Gemara with the commentary of Maharam Shiff. He mentioned Berka Michaelishker[7] – and Yehuda Leib Gordon[8] mockingly, and saw the Haskalah Movement as a madness that befell the Jewish people. The Torah and Six Orders of Mishnah were everything in his eyes. “There is no subject that is not mentioned in the Torah,” was not just a saying in his mouth, but the basis of his belief. He didn't read books of the Apocrypha, and didn't even want to. This is how Meir Leibe, son of the Scribe, lived his independent life which was not influenced by anyone or anything. He didn't change his style of dress or his taste. In summer and winter he wore high leather boots, wore a long coat and a special hat. On the Sabbath, he wore different boots and a Sabbath hat, and a different coat in honor of the Sabbath. He raised two sons – Feive who immigrated to America and settled in Philadelphia, and Zimel. The latter, was talented. He studied in the cheder[9] and in yeshivos,[10] and was sent to the Slovodka [Yeshiva]. When the First World War broke out, contact was lost with him because Kovno was in the area of the German occupation. Rabbi Meir's business declined and deteriorated, his house burned down in the big fire of 1915. His sickly wife passed away in 1918, and then, free from the yoke of raising children and providing for his home, he returned to the kloyz and to the Gemara.

HaRav Lieberman served in the rabbinate and lived at the home of Tsippe Leibe Heishkes on Minsk Street. At that time, the dispute over the rabbinate raged in the town in all its force. HaRav Sorotzkin stayed in Russia and had not yet returned to Steibtz. After the death of R' Shlomo the ritual slaughterer, important members of his family arose and crowned his son, R' Yehoshua Lieberman, as rabbi of the town. R' Yehoshua, a former student at the Slovodka Yeshiva, was a scholar and G-d-fearing, an expert in the Six Orders of the Mishna and Gemara, and a follower of the Mussar movement[11]. He was then serving as the principal of the elementary yeshiva in the town of Eihumen[12] in the Minsk District. Most of the homeowners in Steibtz opposed R' Yehoshua. They simply could not get used to the idea that a resident of their town should exalt himself over them, and become their rabbi. His closeness to R' Meir – who was detached from real life like him, caused R' Meir to be one of R' Yehoshua's most enthusiastic supporters and closest friends, who helped him establish himself in the rabbinate of Steibtz. R' Yehoshua's sermons did not attract a large following, nor did these sermons have much influence, as they were detached from reality or on account of his “exaggeration” in matters of morality which dominated the yeshivos at that time. Sometimes, he went too far with words of Torah which were not understood by the general public. Thus, R' Meir spoke on R' Yehoshua's behalf, and on behalf of various homeowners[13] with whom he met and expressed his opinions to them regarding matters of the rabbinate, according to his way of thinking. He himself never addressed the public because he wasn't a speaker. But, he was very forceful in his personal conversations. His sound logic, keen intelligence, sharp mind and wittedness, worked in his favor, and it wasn't long before a considerable number of homeowners turned into supporters of R' Yehoshua, and this was due solely to Rabbi Meir's ability to convince others.

At that period, my father, of blessed memory, drew closer to R' Meir, and would often converse with him and even became his secret admirer. R' Meir, who was alone and isolated, was now freed from the burden of earning a livelihood, and could disseminate his opinions about the rabbinate among various homeowners. He would visit many of them and, in his hoarse voice shouted or warned, spoke and argued. Most of them didn't understand him and shook their heads at him. Others tried to get to the bottom of his opinion and agreed to his words.

R' Meir had a good friend, Yedidiya Russak the shoemaker, and they also called him by the name, R' Yedidiya, in his presence. R' Yedidiya was an old man, innocent and honest and G-d-fearing, who earned a living from the toil of his hands. He was engaged in shoemaking and set time for studying the Torah at night. His sons grew up and scattered throughout the world, and a few of them remained in the town. R' Yedidiya knew how to read a page of Gemara, and sometimes studied with R' Meir, who liked and admired him very much. He would often relate that Yedidiya, even while serving in the Czar's army, and even when hungry, did not defile himself with a portion of the king's food and never put anything non-kosher in his mouth. Yedidiya did not have a long life and apparently died 1919. The whole town paid their respects, and R' Yehoshua eulogized him. Many people attended his funeral and extolled his good deeds.

R' Meir had another friend, R' Yitzchak Shmuel Epstein, who was the opposite of R' Meir, in that he was pleasant to people and spoke calmly to them. He never gave way to anger. He managed a haberdashery store. He looked after the poor, the sick, and especially Jewish prisoners incarcerated in jail. He would go around every day by himself, collecting challot[14] for the poor and various other necessary food items in his baskets. He also set times for studying the Torah, and every day, after the evening service, he would stay one or two hours in the Great Synagogue to study. He, too, was one of the followers of R' Yehoshua, but he didn't engage in propaganda and never tried to force his opinions on anyone or influence anyone.

He wasn't as fanatical as R' Meir, and therefore everyone liked and admired him. R' Yitzchak Shmuel would read Ain Ya'akov[15] aloud to a group of worshippers at the large table in the synagogue between the late afternoon and evening service.

After R' Yehoshua became established in his rabbinate, R' Meir no longer found a field of activity in the town. He disagreed with various issues. He was unusual and wasn't ready at all to accept other people's opinions, and so he turned to the small Beit Midrash on Putchtova Street, went up to the women's section, placed one bench next to the other, spread over them a sack of straw, which he took from his neighbor Benderovitz – and that served as his bed and a place of residence. After 40 years of a life of buying and selling, he returned to his kloyz to engage in Torah study. He brought his books with him – his old edition of the Six Orders of the Mishna and Gemara, printed in Vilna with commentaries of the Maharam Shiff and Rashi,[16] and all his thoughts and attention were directed to them. Every so often, his sister Chaya Bayla Menaker, would bring him some warm food, and he would have his meals at her table on the Sabbath as well, which was a great honor for her. His diet consisted mainly of bread and a glass of milk, which the Tunik family from Putchtova Street provided for him.

He sat and learned day and night, and between one study session and another he read philosophical books. His favorite books were Chovot Halevavot[17] by the Spanish R' Bahya[18]; eight chapters of the Rambam; Mesilat Yesharim by R' Chaim Moses Luzzato[19] and others. On Fridays he would review the weekly Torah portion with Rashi's commentaries.

He loved my father dearly, and admired him mainly for his great understanding and common sense, and he would keep on coming to our house to chat with my father, and to drink a glass of tea with milk that my mother poured for him. When he didn't find my mother at home, he found his way to the oven or the stove-top, to take out the lak[20] (when the samovar was cold) to find the sugar and to chat a lot.

This was at the beginning of the year 5682/1922. We had finished our learning with Meir Yosef Schwartz. We spoke Hebrew fluently. We progressed in grammar and also finished learning Tanach.[21] We read through the Books of Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah. Since we couldn't go on studying with Meir Yosef my father decided to entrust us to the care of R' Meir, who would be our guide. That was a very bold and original step, for R' Meir had never been a teacher and not even a melamed[22]. My father, however, dared to take this step and we were rewarded. We were four pupils: I, the youngest of the group, was then 11 years old, my brother Reuven, who was a year and a quarter older than me, Mosheleh,

[Page 104]

son of Idel the butcher, and Mordechai Chaikel Prusinovski. We began to go to the small, far-off Beit Midrash, to study with R' Meir.

The walk to Neiman (Nadnimenskah) Street passed through the unfenced gardens to Vilna Street, from there to the synagogue's lane, along Vilna Street populated by non-Jews in that section, until we reached the home of the Yantchur family, who lived at the corner, and from there to the synagogue.

The synagogue was built of wood with colorful windows. At the entrance to the Kahal Shtibel[23] lived the honorable Reb Chaim Moshe the Shamesh. He was very stern and we never saw a smile on his face. When his wife, Reitze, died he married Chana – the widow of Berel Eli, who died at the same time, and they lived their quiet life in the Shtibel. His job was to sweep the synagogue once a week, the yard, to clean the glass windows of the lanterns once a day, and to light them between the late afternoon and evening service, and –on the days of reading the Torah – to say “May His kingship over us be revealed and become visible soon”[24] before the reading, and “Our brothers, the entire House of Israel” after the reading, and then to tap on the charity box – a clean and easy job he got from the gabbai, Leibe Feive's son, (Komak), who ruled high handedly after receiving the position of gabbai as an inheritance from his father, Feivel Shmuel, Natan's son. He was bearded, tall and thin, and wore a shirt and frayed coat all year long.

This was the environment in which we studied with R' Meir. We had our class in the women's section in the southern corner because R' Meir's bed was in the northern corner. This was the view which was seen through the windows: on the east was Bendorovitz's yard, which was always full of geese, and on the south was Yantchur the Fisherman's yard and his spread-out nets, and on the west were the ruins of traces of (his son? – meaning unclear), of whom it was related that this was once the center where he kept his merchandise and sometimes served as a place to hide goods for the boats which sailed down the Neiman River to distant places as far as Germany, Kovna[25], Memel[26]. In our time, the ramparts stood in ruin: three walls as high as two floors were built partially out of stone and brick. The ruins of a wall of low wooden houses in the area seemed like a heroine who had descended from her greatness but still remained very proud, the ruins protruding in all parts of the surroundings.

We continued our studies with R' Meir in that way throughout the winter of the year 5682/ 1922, from morning to evening, with a break for lunch. The walk to the small Beit Midrash was not considered the easiest thing at that time. It was quite a distance away in our estimation, and the mud was deep in the autumn. In the winter we trampled through the deep snow and we encountered dogs belonging to the Meishtchins[27] from Vilna Street and we were also afraid of the Christian boys. At Christmas time, non-Jewish boys would go out into the street with their kalides[28] and then the danger was even greater. Then we would walk together so that no harm would befall us.

Our study consisted of Gemara, Rashi's commentary and Tosafot[29], and on Thursdays and Fridays, the weekly Torah reading portion with Rashi's commentary. We studied Gemara- Tractate Bava Metzia – very thoroughly, of which we managed to learn 50 pages during the winter months, including the chapter Hazahav[30] combined with the complicated subject of “merchants of Lod” with Rashi's commentary and Tosefot. R' Meir was really a very good teacher. He explained well and derived much pleasure when we understood the subject, and the reward for our good understanding was a really strong pinch on a sensitive place. Our class was neither a cheder nor a yeshiva. We were 11 to 12 years old and I was the youngest of all the pupils, but Rabbi Meir related to us as to older boys. He certainly didn't use the “kantchik” [rubber strap], and didn't need to, as we were devoted and attached to him, and we swallowed every word that came out of his mouth. This was learning Torah out of full recognition of our aim to be learners of Torah for its own sake, and R' Meir imbued us with this mission in a systematic way and he did so very successfully. He never preached morality and never rebuked us on account of our deeds. This was completely contrary to his method and was hateful to him. On the other hand, he imbued our hearts – knowingly or unknowingly – with his method of thinking. His unique philosophy was the following: the world is divided into those who study Torah and those who don't, and it's better for a Jewish person to be among those who study Torah, for in any case what is man's superiority over an animal, and what else does he have in this world? He meant precisely this world because there is no greater pleasure in this world than studying Torah. His slogan was – Engage in Torah! And he himself fulfilled this objective and after an exhausting day of studying Torah until 9:00 pm, he ate a small piece of food – bread dipped in milk – and then ran down to Beit HaMidrash and studied until the morning while reading the Gemara aloud in his hoarse voice, immersed in his favorite commentaries – those of the Maharam Schiff and Rashash – R' Shmuel Strashun[31] from Vilna, whom he admired with all his soul. He didn't know R' Strashun personally, but, on the other hand, he knew his son, R' Matityahu Strashun in Vilna, in whose name the great Strashun Library in Vilna was founded.

He didn't prolong his praying very much, although he was exact in expressing the words and his praying was not hurried. He didn't like the mannerisms of prayer, and when the prayer leader repeated the 18 Benedictions prayer, even on the Sabbath, when the prayer leader would trill his melodies, R' Meir would prefer to read a book. He would often cite ideas from the Sephardic R' Bachya's work, Chovot Halevavot, which was the philosophical and intellectual basis for faith and fear of G-d. On the other hand, he didn't read many books on ethics or rebuke, which lead to spiritual awakening and fear of G-d, and considered this to be neglect of Torah study. At every opportunity he talked a lot about the Vilna Gaon and told us about his greatness and his genius. This was in the year 5682/1922, and the Vilna Gaon passed away in 5557/ 1779. Although 125 years had passed since the death of the Vilna Gaon, in the eyes of our rabbi and teacher, it was as though the Vilna Gaon was still sitting and studying Torah and participating in the service in the Ramayles kloyz in Vilna, wrapped in his prayer shawl and adorned in his phylacteries. “This is what the Gaon was accustomed to doing,” “This is what the Gaon would say,” “The Gaon said,” – these words and the like. All his desires were that we adhere to the Vilna Gaon and walk in his ways. He described the Gaon's life and customs to us. We knew that HaGra[32] slept a total of two hours a day, and even that not all at once, but in half-hour installments. We knew what foods he ate, his customs and his relations with people and his children. In addition, the rabbi emphasized that HaGra deciphered all the mysteries of the Torah, and found in it an allusion to everything that occurred in the world. As it is said, “There is nothing that is not mentioned in the Torah.” And besides that, even the cantillation marks for reading the Torah had certain clear signs and meanings for those who possess hidden wisdom. And I remember his lingering on the verse “And Judah came closer to him.” [Genesis 44:18] The cantillation marks over these words are kadma and ozla and r'vi'í, meaning, that the fourth advanced and came – the fourth being Judah, who was the fourth of Jacob's twelve sons. And this is just one tiny example of the allusions, secrets and mysteries that envelope every verse in the Torah. Every word, every letter, ornament or crown are allusions not only to the Divine source, but they actually allude to every single event in the world in the past, present and future, both in particular and in general.

And the rabbi informed us about the “external wisdoms,” which HaGra learned in places where it was forbidden to learn Torah, about astronomy and mathematics and about the order he gave his friend, R' Baruch of Shklov,

[Page 105]

to translate these books of science into the Holy Language, and, of course, the rabbi spoke about HaGra as a grammarian.

The rabbi's words flowed quietly and logically, penetrated our hearts little by little, were etched in our memory and brought us back to a different period, to the period of HaGra from Vilna. The rabbi would often read us the famous letter that the HaGra wrote to his wife and children on his way to the Land of Israel – Alim L'Trufah[33] – words of admonition and rebuke in order to stay away from hatred, jealousy and gossip. He ordered his wife not to go to the synagogue, because she would see fine clothes there, become jealous and will tell [about the clothes] at home, and in doing so, G-d forbid, would engage in gossip. “Behold! People are travelling to see the object of desire of all the Jewish People.” And of course the saying – vill nar gaon, that is to say, “if you only want to, you, too, can become a genius.“ This saying never departed from the Rabbi's mouth, an appropriate saying with great educational power. Every person, with his own power, can reach the understanding of the ma'asei merkavah[34] with exertion and toil. And didn't our Sages say about this verse: “If a person dies in his tent…[35]” – “Our Torah is acquired only by someone who kills himself over it”.

In this manner the rabbi instilled the importance of learning Torah into our hearts, and the importance of the intellectual effort by which one can reach the understanding of ma'asei merkavah.

We studied three terms with R' Meir – the winter and summer of 5682/1922, and the winter of 5683/ 1923, but he succeeded in bringing us back to the period of the Vilna Gaon and his pupils.

One day he came and joyfully announced the good news of the birth of his twin granddaughters, and, from then on, he changed his relationship with his son. He began to visit him and help him in his business and found the “Power of Permission,”[36] because he was doing this for his granddaughters and not for his son.

He gradually returned to his store and to the grocery business, in which he was engaged during most of his stay in Steibtz, but he continued to live in the small Beit Midrash with his second wife Liba, a village woman. He engaged in the study of Torah at night and studied Gemara with his favorite commentators, the Maharam Schiff at their head.

We pursued our learning in the elementary yeshiva founded by R' Yehosha Lieberman, the town rabbi. He appointed R' Simcha Plotkin, a pupil of the Slovodka Yeshiva and a follower of Mussar, as our monitor. R' Plotkin introduced talks regarding Mussar into the yeshiva curriculum as was the custom of the upper-level yeshivos, and thus we distanced ourselves from R' Meir, and he from us.

Time went on, and I studied at the nearby Mir [Yeshiva], where R'Yerucham Leivovitz, who had become famous as one of the great instructors of the Mussar, was then teaching. He was an outstanding pupil of R' Zissel of Kelm, and they came from all over eastern Poland, Rusyn [Carpathian Ruthenia] and Lithuania to study Torah in Mir and hear R' Yerucham's lectures. On one of the eves of Rosh Hashanah, I saw R' Meir at the yeshiva, stern and closed within himself. He was wondering what was going on in Mir and hear about R' Yerucham and his Mussar method. He stayed until after the Day of Atonement, heard all the lectures of R' Yerucham, of blessed memory, heard and listened attentively, and went deeply into the subject but was not convinced or influenced. As though disappointed, he returned to Steibtz just as he had come, but sevenfold more lonely and isolated. He asked R' Yerucham: “What do you want? Isn't studying Torah enough? For what purpose is there a need for spiritual awakening, and doesn't a Jew know what his duty is in his world?” He returned to himself and to his period – the period of the Vilna Gaon. He returned to his days at his son's store and his nights of Torah study, far from his town and his former pupils, he lived outside his place and outside his time.

I didn't hear about him for many years, and I didn't know what fate had in store for him. With the arrival of the first reports about the Holocaust, I found out that he left his Beit Midrash when the Nazis arrived, and walked to Turetz, to his younger brother Shmuel, and on the tragic day of the holy community of Turetz, in the month of Marcheshvan 5702/1942, wrapped in his prayer shawl and adorned in his phylacteries, he was led to the slaughter with all the residents of Turetz, may G-d avenge their blood, the last of the Vilna Gaon's pupils in our generation.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Jan 2024 by LA