|

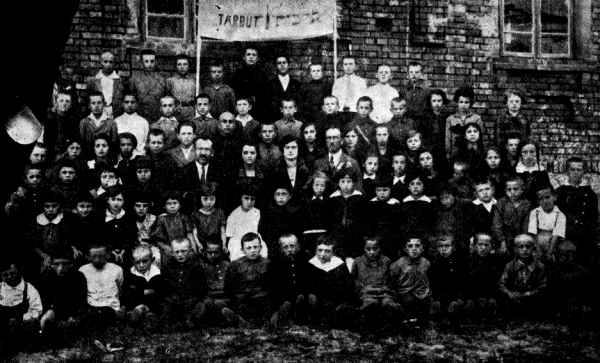

In the center of the picture, the teachers (R–L): Alter Yossilevitz, Mrs. [Chana] Danzig, Leah Tilman, Meir Yosef Shwartz

|

|

[Page 88]

by Mordechai Machtey

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

Steibtz, unlike Mir, was not a town of Torah students. The sad–sweet melody, “Give up hope”[1] said Rava; “Don't give up hope” said Abbaye[2] was seldom heard bursting forth from the confines of the study hall during the day. And should it happen that this voice was heard, it was a feeble reaction more reminiscent of the cooing of doves than the voices of students trying to grasp an idea in the Gemara[3]. I recall two boys from my childhood who studied in the study hall during the day. They were my brother Aharon – May G-d avenge his blood! – who left the yeshiva or, as it was then called, Beis Ulpana in Mir, and Alter Yossilevitz, who had recently come to Steibtz, and with whom Aharon made friends and they studied together. The picture between mincha[4] and ma'ariv[5] was different: the important members of the synagogue who had retired from business, those who hadn't forgotten their childhood knowledge, would take advantage of the break between mincha and ma'ariv and apply themselves diligently to their learning, whether one who joined a group of Sha"s Talmud learners, or one who preferred to study alone and learned his chapter in the light of the candle attached to the learner's stand (“shtender” in Yiddish). And those, for whom the paths of the Gemara were not clear, would gather next to the two tables behind the stoves on both sides of the doors and listen to the lesson on Ein Yaakov[6] or read chapters of Psalms. Others spent their time in conversation with friends or discussing current events.

There were only two Gemara teachers in Steibtz worthy of being called “teachers”: Reb Binyamin Cohen (Bunia the Teacher) and the judge, Reb Yehoshua Medvitsky (who had moved to Baranovitch to serve as judge, and perhaps the supply was in accordance with the demand, that is to say, there were not many students whose parents wanted to cram them with knowledge from the “sea of Talmud”.

When we got older, my father and Zalman Shazar's father took the trouble of acquiring a teacher for us and they found the Parush[7] from Koidenov (See Zalman's story “Haparush mekoidenhove”[8]). After 3 terms (a year and a half), when the Parush left the town, there was no other teacher in the town for me, and so my father sent me to Mir, but not to the yeshiva[9], as I had not yet reached the rank of yeshiva student, but rather the level of a pupil in a Talmud Torah[10] class where the teacher was Rabbi Zhama from Korelitz. Unlike the Talmud Torah in the small towns, where the sons of poor families studied starting from the very beginning and finally advanced to a chapter of the Bible, the pupils in Mir studied only Gemara in the Talmud Torah, and not only sons of poor families but even sons of well–to–do families. The seating arrangement in Rabbi Zhama's class was interesting: the pupils sat in a semi–circle, and the Rabbi's table was in the middle of the room so he could surround all the pupils. He introduced a system of grades, but not written marks, which only the pupil sees and can hide from his friends. The marks were according to seating places: the best pupil would sit at the left end (to the right of the rebbe), and the poorest pupil sat at the right end (to the left of the rebbe). When the pupil saw the fruit of his labor, the rebbe would move him one place or sometimes even more – everything according to the measure of his progress. The rebbe would take out of his class the pupils whose knowledge was not up to the level which the rebbe himself determined and moved him to a lower class taught by Rabbi Reuven from Turetz. Rabbi Zhama's power of explanation was great and his influence on the pupils was considerable. And after one “term” or, at the most, two or three, the pupil was accepted at the yeshiva. And thus I was accepted at the Maltsh Yeshiva after only one “term”.

As we see, Mir, unlike Steibtz, was a town where Torah learning flourished. And in 1911 Mir was struck by a fire in which not only the yeshiva building was burned down but also many other buildings, the majority of which served as lodgings for yeshiva students, who were left without any shelter.

[Page 89]

In this situation, they sought a place to transfer the yeshiva until the destruction in Mir could be repaired. The fate befell Steibtz, whose capacity to absorb newcomers suited the yeshiva students. And so the Mir Yeshiva moved to Steibtz. This was something unusual. During the day, the learners' voices began bursting forth from within the confines of the old study hall, arousing much interest. It was also nice to get to know the yeshiva students, who were not different from others in their dress and also didn't grow a beard or side–locks. Apart from the fact that they were no different from the rest of the town's population in their manner of dress, it was clear that these were people to whom the ways of the world were not foreign and that you could talk to them about all the problems that were then on the agenda. These were people with whom you could become friendly despite the fact that their outlook on the world was different from that of all the young people. One of the pupils, Avraham Lis or, as he was called, Avraham from Vasilishuk, rented a room in the home of one of my friends and we became friends. Even after he left the yeshiva and lived somewhere else with his family, he would visit me every so often whenever he came to Steibtz to tend to his affairs.

The climax of interest in the yeshiva was reached when they celebrated the “Rejoicing of the Water–Drawing Ceremony – Simchat Bet HaShoeva” – on the Festival of Tabernacles. This was something which never took place in Steibtz before or after, and for eight days the old study hall was filled from end to end, and many people also took part in dancing and singing. The inspiring song, Tzadik KaTamar[11] still resounds repetitively in my ears, and, they would dance till the point of exhaustion. These were truly moments of the uplifting of the soul and heartfelt happiness, such as which there aren't many in one's life.

The Mir Yeshiva did not stay in the town for a long time. The big fire which burned down the homes of most of the Jews as well as the study halls on one hand and the restoration of the ruined buildings in Mir on the other hand, enabled the yeshiva to return to its previous lodging place sooner than planned. The memory of those days has remained etched in my memory until today.

The Korobka[12]

I don't know the source of the name korobka, which is called di takseh (tax on kosher meat) in the works of Mendele Mocher Sforim[13]. It seems to me that the name has a connection to the Russian word korovka, which means a little box made of cardboard or wood. Its full name is korovotchni savor. If my memory serves me right, the tax income was intended for supplying the community with religious articles.

Those in charge of the income were government clerks, since there was no officially recognized Jewish body, like every system of collecting taxes in Czarist Russia. There was also a korobka that was a sort of indirect tax, which was levied on every liter (pound) of kosher meat. Steibtz, which had ties with Germany, also received Germany's unit of weight, which is to say, that in addition to the Russian pound, whose weight was approximately 400 grams, the “Berlin” pound, whose weight was approximately 500 grams, was also combined. Meat alone was sold according to the Berlin pound. The rest of the trade items were joined to the Russian pound.

For kosher meat, the butcher paid for the front part (minus the head), legs and internal parts. They first weighed every slaughtered thing and then paid according to that. In the course of time, they moved to an appraisal method, meaning that the person who held the lease on the korobka came to an agreement with the butcher over the estimated weight and paid him according to that. Afterwards, there was a fixed payment for a cow, bull, calf and a sheep. I don't know of any case of raising the payment, or that they came to criticize him as a result. As the well–to–do often ate chicken, the korobka was also levied, in the form of a fixed payment for chicken, ducks and geese. In the months from Av to Tishrei[14], the payment was reduced for chicks. The slaughterer had to get a payment slip from the korobka before slaughtering the animal. The korobka on fowl was not connected to the general korobka and was leased separately.

The town leaders or, as they were called the seven town worthies, although their number was sometimes less or more than seven, used the korobka tax for the numerous needs of the community, including the repair of the public bath house because Shaul the bath attendant always claimed that the income from the bathhouse was not even sufficient for the repairs. Every recruit taken into the army received a grant from the money inside the korobka box. The amount of the grant was between 10 to 15 rubles. Besides the butchers' sons, who received from 25 to 35 rubles on the pretext that their parents were the ones who put the money into the korobka box, a decent amount of money was also taken out for the maintenance of the ice cellar, in which blocks of ice were collected and stored during the winter and, in the summer they distributed ice pops in sacs to the sick to reduce their fever according to the doctor's instructions and for various other needs.

The town rabbi leased the korobka from the government and later on they leased the korobka in a public tender, which took place in the large study hall. The rabbi offered to pay the government a sum of between 300 and 400 rubles, but the leaseholder made a higher bid of 2,000 rubles for the korobka.

From my childhood days, I remember Shraga Kumak (Feive Shmuel Natan's son) – Miriam Kumak's grandfather, who would lease the korobka and later Tzion Dov Reichman (Chaya Stisin's grandfather), who raised the bidding price, won the tender and held on to it till his death. The last leaseholder was Chaim Tunik (Chaim Moshe's son), until it was cancelled with the outbreak of the First World War and the Steibtz fire, which occurred on the 12th of Sivan, 5675 (May 25, 1915).

Another community tax came into being and that was a payment for Sabbath candles. I remember that my mother would send me to Isaac the Candle Maker, Dov Berkovitz's father, to buy Sabbath candles. They used to make the candles from tallow, and it's hard to describe their foul odor on the Sabbath Eve when we sat around the table for the evening meal. The payment for Sabbath candles was cancelled during the first years of the present (20th) century.

The Burial Society

From earliest times, there was a group in every town which took care of the burial of the deceased and was known as the Burial Society (chevra kadisha).

Its members were volunteers, and except for the gravediggers, not one of them received anything whatsoever in exchange for their toil during the summer and winter when the cold sometimes reached 25 degrees (C) below zero. The women, too, who were engaged in sewing shrouds, did their work voluntarily and with the feeling of performing a final deed of benevolence.

[Page 90]

The members of the Society were divided into honorary officers, those actually attending the deceased, escorts and bearers of the deceased. The work of those attending the deceased was to cleanse the deceased before their burial. Arrangements of cleanliness were not at the appropriate level and maintaining the body of the dead person in known conditions sometimes endangered the lives of those taking care of them when they came into contact with the deceased (in the case of infection and epidemic). It was therefore customary for those engaged in cleansing the deceased to treat themselves to a few glasses of brandy beforehand, and this custom has remained so to this present day. The Society would maintain the old and new cemeteries with burial fees which they charged the families of the deceased according to their economic status.

Apart from the meal served on the 15th of Kislev, the Burial Society was accustomed to bringing together its members on the Sabbath when there was a kind of hint in the Torah portion regarding the Society's roles, that is to say, for example, on the Sabbath of the Torah portion Beraisheet[15] when the Hebrew word, vayamot, (“and he died”) is mentioned several times. On that Sabbath, only members of the Burial Society were called up to recite the blessings on the Torah and its own gabbai[16] would distribute the aliyas[17]. After the service, they would gather in the gabbai's house for a conclusion, following which they drank a glass of brandy. This was called in Yiddish lekach un branfen[18].

15th of Kislev

The Burial Society in Steibtz set the 15th of Kislev as a day of fasting with a meal served afterwards at the conclusion of the fast. It was a fast with the recitation of penitential prayers and with the Torah reading “And he began…”[19], as is customary on public fast days. The source of this custom is connected to the Jewish approach to the deceased, to whom it is forbidden to show disrespect, and in order to atone for any possible sin of this kind, they set a public day of fasting on the 15th of Kislev. Why precisely on this day? I found among the literary remains of my uncle, Rabbi Yosef Yeshayahu Cohen, of blessed memory, that the 15th of Kislev never falls on the Sabbath.[20]

Those who mainly fasted were the honorary officers, and those caring for the deceased, those cleansing their bodies on their final journey and the gravediggers. As the members of the Society exerted themselves without expecting any reward, the meal served after the fast was copious. Since the month of Kislev was designated for the slaughtering of fattened geese, they would slaughter a lot of them so that each person would receive a quarter of a goose and take part in heavy drinking.

In the course of time, the fast and the meal after the fast became a routine matter and many people thought it was a memorial celebration of the Society itself.

Translator's Footnotes

by Eliezer Melamed

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

Between the two World Wars, Zionist education occupied an important place in the life of our small town. Every household strove to provide its children with traditional Torah or Zionist – secular learning. A tuition fee which constituted a considerable amount in the family's budget was set.

There were two types of schools in our small town: The Chorev school, to which children of religiously observant and traditional families were sent, mainly from homes which opposed the idea of Zionism. This school was founded and supervised by Rabbi Yehoshua Lieberman, of blessed memory, an opponent and daring fighter against the idea of Zionism. The other school was a branch of the network of Hebrew schools founded by the Tarbut organization, whose object was to provide Hebrew and general education and to foster a connection with the people and the Land of Israel. Children of Zionist parents and lovers of Hebrew attended this school.

Members of the Bund[1] party, standard bearers for Yiddish, whose number was quite significant among us, sent their children either to the Chorev religious school or the Tarbut Hebrew school or straight to the Polish public school as there was no Yiddish school in our local town.

The Tarbut school was founded in 1922 by the teacher Alter Yossilevitz, who returned to our town from Minsk in the first years after World War I. He was an ardent Zionist and was devoted to the idea of Zionism in general and to Hebrew education in particular. He was ready to fight for his beliefs at any time. His way was not paved with roses. There was no shortage of opposition and disturbance. However, possessing momentum and great energy, he overcame all the obstacles and established an educational operation worthy of praise and admiration. Hundreds of teenagers, boys and girls, who acquired a Hebrew and secular education based on the spirit of Judaism and Eretz–Yisrael[2] graduated from this school.

I remember very well the festival parties that were held at the school. Two rooms were partitioned off by a wall and during an important event or festivity, they would shift the wall to the sides in such a way that a large area was formed which could accommodate many children. On the eve of every holiday, all the children would assemble in this spacious auditorium. Alter the Teacher would open the program with a comprehensive explanation of the content of the holiday or the event from an historical–nationalistic point of view. His words always raised the spirit of the pupils, who would disperse to their homes enthralled, after the festivity.

Alter Yossilevitz was also the center for Zionist work in our town. He would always open the explanatory meetings on behalf of the national funds[3] as well as the meetings in advance of the elections for the Zionist Congress or the parliamentary institutions in Poland. This thin, tall man with a small beard would stand at the rostrum of the old study hall, and exciting words would emanate from his mouth. His very appearance would imbue us with a supreme spirit. Opposition party members would interrupt his remarks at these meetings. This upset Yossilevitz to such a degree that he would often require medical help after such an incident. He suffered from a heart illness and his doctors forbade him to get riled up. However, he didn't heed their advice as he saw his work on behalf of the community as the purpose of his life.

All the people of Steibtz, especially those who studied in the school, will recall the image of the Teacher Alter Yossilevitz (for he was thus called in Yiddish, Der Lehrer Alter by the public). Trembling with respect and admiration, they will elevate his worthy deeds to the level of a miracle in our town for the education of an entire generation of Jews, to which he was devoted with all his soul and faithful to the values of his people.

His colleague was the teacher Meir Yosef Schwartz. The two were as different from one another as day and night. I imagine that they studied in cheders[4] or in yeshivas[5] when they were young and in the course of time they completed their studies on their own. Meir Yosef came to us from Eretz Yisrael, where he had gone to live as an immigrant during the Second Aliyah[6] and who returned to the Diaspora due to poor health. He was a cripple. Severe crises which befell the country [Eretz Yisrael] at that time caused him to return to Europe. He was accepted as a teacher in the Tarbut school. According to his outlook, he was an ardent Zionist and

[Page 91]

one of the supporters of the religious block in the Zionist movement Ha'Mizrachi[7]. He was irascible by nature. He was accustomed to telling the pupils exciting stories about life in Eretz which aroused warmth and love for the legendary country in the children's hearts. He was devoted to his work and profession, possessing the ability to explain things well and was meticulous regarding every interpretation and elucidation. He was an expert in Scripture and had a deep knowledge of Hebrew literature. He also taught crafts and drawing. On a holiday or at the end of the academic year a play was presented by the pupils. The main executor of the play was Meir Yosef: he was the planner and producer, he built the scenery by himself, he adapted the melodies and tunes for the songs that were sung in the play. In addition he would teach a page of Gemarah[8] to the older pupils. This lesson would take place as usual in the last hour of the school day after the youngsters had gone home and quiet reigned within the school. We delved into a page of Gemarah and we enjoyed the hair–splitting arguments and the clarifications. Meir Yosef the teacher treated us like equals. We had lengthy friendly and cordial conversations which interested all of us. At the end of our conversations he used to say: Well, “hodzi” – (that's enough) to inform us that the free conversation was over.

Bitter was the fate of the disobedient and unruly pupil or the one who did not do his homework. He got his share of curses and revilement. One incident involved our classmate Yosef Harkavy. He was an excellent pupil and a stickler for accuracy, but he violated some prohibition in the opinion of the teacher Yosef Meir Schwartz. Since he was by nature a bad–tempered person, he grabbed the pencil box and slapped him in the face with it. From the force of the blow or from the sensitivity of his gums, a tooth had to be extracted. Schwartz the teacher, who became alarmed and who did not know how to ease the tension, claimed, in opposition to his pupil: “Why are you making such a fuss over this? After all, only one tooth fell out”….

Schwartz the teacher's life came to an end in a mass grave. During the period of the German occupation, he lived in the adjacent small town of Swerznie and was a member of the local Jewish council (Judenrat[9]) charged with overseeing daily activities in the ghetto. During the first massacre, he was among the candidates selected to remain alive, but he, of his own free will, chose to go to the mass grave together with his family and all the residents of the town.

Translator's Footnotes

by Tamar Amarant (Rabinovitz)

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

I see the Tarbut School building before my eyes. It was a square four–room building. There was a library in one room for the use of the pupils and opposite the library were two rooms separated by a moving wall. When there was a festivity, the moving wall could be pushed to both sides, creating a long room which also served for school plays.

The rooms were very crowded. The furniture consisted of long benches and long tables. When a child wanted to go out,

|

|

In the center of the picture, the teachers (R–L): Alter Yossilevitz, Mrs. [Chana] Danzig, Leah Tilman, Meir Yosef Shwartz |

[Page 92]

the whole row had to get up, or the child would crawl under the bench and suddenly his head “sprouted” near the door.

I remember that in these four rooms the following teachers, of blessed memory, taught me: Reb Alter Yossilevitz, the school principal, who taught Hebrew and grammar. The teacher Reb Meir Yosef Shwartz taught Torah and Nach[1] and the teacher Leah Tilman taught arithmetic. As there was no staff room, the teachers would crowd together with the pupils during recess and while standing, they would sort out many issues, but in that crowded school house, there reigned incomparable warmth.

Were the teachers graduates of seminaries? I don't think so!! But apparently they were teachers from the womb, from birth. Their faces were pedantic, but the teachers' warmth enveloped us – the pupils, like protective armor, stimulating us to study, review and memorize so as not to disappoint the teacher, G-d forbid, or fail. Where did the teachers get their strength from? I think they loved their profession and they loved us. Without any systems of methodology and pedagogy, they knew how to maintain control in the class and hold sway over our souls.

Exemplary brotherhood reigned among us. I do not recall any “hitting” in school. I can attest now, as a teacher, that our children are blessed with over–aggressiveness, and one child cannot forgive another for a gentle nudge – and then? Did the “gentiles” who lived around us have an influence, that we always knew how to maintain peace and quiet and good manners and courtesy?! Were our households different? What was the source of such restraint? Our games too were quieter and more restrained. Behind the school, which was located between two synagogues, there was a very wide lot in which we found our satisfaction– playing games. I still remember Yossilevitz the teacher's lessons–there was no more noble and delicate soul than his. Despite his serious appearance, his cordial laughter and warm eyes always aroused in my heart a desire to know everything and to excel in my knowledge. No spur was necessary for learning. The teacher's quiet remark was sufficient. I still remember a few complete chapters from the Book of Jeremiah, which the teacher Shwartz of blessed memory taught me. His sweet melody still resounds in my bones.

“What do you see Jeremiah?” “I see an almond staff.” The melody would reveal Jeremiah before me wearing a broad cloak, with a long beard and sadness in his fathomless eyes. And this teacher who, because of his bad temper, was not the favorite of the pupils, knew how to open the children's souls in preparation for a chapter in the Bible.

A few decades have gone by and I still remember these chapters by heart as if I had just learned them yesterday.

And from this crowded school emerged culture, politeness, and Torah.

Translator's Footnote

by Mordechai Machtey

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

As if peering through a fog, I see one of the remnants of the former institutions of the community of Steibtz – the Hekdesh[2] which, like all the houses in Steibtz, was an old wooden building on which the hands of time had taken its toll.

The building was located next to the old cemetery on the east, where all the institutions were concentrated: the Cold Synagogue (Di Kalte Shul[3]) because there were no heaters to provide warmth. In the Cold Synagogue there was a really unique Holy Ark, the work of a craftsman, a carpenter, which fascinated the eye of the beholder with its beauty and engravings. I remember that when painters came from Minsk to paint the New Study Hall and, seeing the Holy Ark, they were so impressed that one of them brought a gabbay[4] from Minsk who was enchanted by its beauty and appraised its value at 10,000 rubles.

Near the cemetery on the south was the public bath house, a stone building in which there was a mikveh[5], and those who came to immerse themselves had to walk down about twenty steps. To the east of the public bath house was the slaughterhouse, part of which served as a replacement for the Hekdesh when it was destroyed. Next to it were the butcher shops, and until a slaughterhouse was built, slaughtering was done in the butcher shops. After the butcher shops was the communal prayer house which served the Lubavitch Chassidim (members of Chabad[6]) and the Chassidim of Koidanov[7], after the Lubavitch prayer house opposite the cemetery on Paromana Street burned down.

The name Hekdesh testifies to the fact that the building was founded as a kind of hospital in miniature, since the name Hekdesh was customary as a name for shelters and Jewish hospitals. The hospital of the Jewish community in Minsk was also called Hekdesh. In my time, it already served only as a rest home or place to spend the night for beggars on their wanderings. When they arrived in Steibtz, they delayed their stay here for some time. In the building there were two rooms and a corridor which, it seems, belonged to the Chevra Kadisha[8], but I don't remember who actually took care of it. The building was wretched, both in its essence and its cleanliness. The windowpanes were broken and smashed and in the winter were blocked with pieces of old rags. The roof, too, was not in good repair. No one took care to renovate its ruins, striving to make sure that the building no longer had any use in order to get rid of uninvited and undesirable guests.

In 1895 they tore down the Hekdesh and began to build a study hall called “The New One” to distinguish it from the Large and Old Study Halls. After they started digging the foundation, they came across a leg bone and, as it was in the vicinity of the cemetery, the suspicion arose that perhaps it was in fact part of the cemetery and out of fear of ritual defilement, the priests would not be able to pray there. They had to ask a doctor to determine if the bone was that of a person or of an animal, and when they turned to Rabbi Shlomo Mordechai Brodni for his opinion, his decision was that it was the bone of an animal.

Instead of whitewashing the study hall as was customary, they decided to paint it with oil paint. Moreover, they didn't rely on the painters from Steibtz and brought in painters from Minsk, who painted the walls, and the ceiling was also decorated with drawings such as the four species[9] etc. Perhaps they also wanted to copy in paint the etchings and engravings on the Holy Ark in the Cold Synagogue. And something else new was introduced into the building: as there were no heating stoves on both sides of the door, they dug a pit in the middle of the building where they erected a large square–shaped stove which would rise about a meter above the floor and served as a platform. This stove would be lit twice a week, filling the study hall with pleasant warmth. The new building made a very good impression, but not for long. In 1902

[Page 93]

|

|

a fire broke out in that area and the Cold Synagogue including all its rooms went up in flames along with the New Study Hall, the Shtiebel[10] of the Chassidim and the butcher shops.

A popular proverb says that one gets rich after a fire. This saying came true in full regarding the New Study Hall. The wooden house burned down and a brick house was erected. The new building was larger than its predecessor. It was built of brick and had a tin roof. The internal decorations were also executed by artisans from Minsk. The gabbays of the Large Study Hall were envious of the new building and they too began to renovate it. They painted it with oil paint, removed the heaters alongside the entrance, and in the center of the building built a stove above which a platform was erected.

An evil eye also harmed the New Study Hall. The first building was destroyed by a fire five or six years after it was erected, and the second stopped functioning well before the Holocaust and with the coming of the Soviets at the end of 1939, it was converted into a movie theater.

Translator's Footnotes

by Zvi Stolovitzky

Translated by Harvey Spitzer z”l

We are talking about educational institutions of an outstanding religious character that were founded and existed in our town between the two world wars and during the tenure of Rabbi Yehoshua Dov Lieberman. He served as town rabbi of Steibtz and lovingly cared for these institutions and regarded his attention to these, as his main function.

Talmud Torah[1] Chorev

This school reopened in the 1920s with only four classes, but its founder, Rabbi Yehoshua succeeded in attracting and engaging teachers with excellent educational abilities, the foremost of which was R'[2] Yehuda Kapushchevski. He was a native of Lubtch and a resident of Derevna, and with his arrival, the big school flourished. He taught Bible, Hebrew, and Gemara[3]. He accompanied his teaching of the Bible with a heart-felt melody and with his eyes closed with emotion, as the students read the verses. In the Gemara lesson, he was accustomed to emphasizing the difference between the study of Gemara and that of the Bible. During the study of the Bible, it was sometimes possible to continue learning a chapter, even while listening to a defective reading of the previous verses. However, this does not apply to the study of Gemara, which requires consistent, rigorous concentration, otherwise, the essential link to the subject would be lost. Reb Alter Koznitsov taught the Pentateuch[4], reading and writing, and Tania Volfson taught math, language, and Polish history.

The school was officially approved by the Polish authorities and also won recognition from the municipal council (Magistrat), which allocated annual support, sufficient for paying the salary of the Polish language teacher. Rabbi Shlomo Khari served as official principal vis–a–vis the authorities.

Some years before the outbreak of the Second World War, the number of students in the school had grown to such an extent that it required considerable expansion. The small school building which was on the Shulhoif[5] was enlarged and an additional floor was added for the absorption of its 150 students (boys). We must point out that this was made possible by the devotion and contributions of the residents of Steibtz itself, without external assistance, and with Reb Yosef Miskov as the driving force behind this project. Both Rabbi Yehoshua Lieberman and Rabbi Yoel Sorotzkin took part in the inauguration of the new school. A considerable number of the graduates of the school continued their studies at the small yeshiva[6] that had been established in Steibtz, and at other yeshivot as well.

Beit Yaakov

This school was intended for the education of girls; the lack of this facility was felt for many years until the year 5694/1934, when the talented teacher, Esther Berman, was brought to Steibtz from Grodno, and the school was then established. (She serves today in the field of education in Rehovot). The school, that was established in glory, was housed in a building in the Yurzdika neighborhood, on a plot of ground belonging to R' Elia's son, R' Nachum, a man of Torah learning

[Page 94]

and mystery, who lived in Steibtz until the outbreak of the First World War. The history of the establishment of this two–story building also reflects self-sacrifice and voluntary spirit. The building was under construction for a few years and the residents of the town, many of whom were close friends of Rabbi Yehoshua, carried the burden.

Ms. Berman (Koppelevitch) the teacher, remained in Steibtz for two years, during which time she succeeded in garnering support for the idea of educating girls in the spirit of tradition. Aside from the primary religious studies, they were taught general studies, as well as singing, recitation, and dance. After a few months, the school began to display its achievements at a big reception that took place in the local Novoshtshi movie theater. In the auditorium filled with spectators, with people of all social levels of the community, including the intelligentsia, the school's development was demonstrated in singing, drama, and ballet. I recall an interesting episode from this presentation: Rabbi Yehoshua did not prevent the younger yeshiva boys from attending, observing and enjoying the fruit of the Rabbi's labor that he had invested in the school. Only his protégé, the Rabbi Reb Dovid Shmuelovitz, who was still young then, was forbidden to attend this show.

Ms. Berman the teacher, organized a club was called Batya, that consisted of Jewish girls who were students at the Polish public school. They would meet in the afternoons and evenings and the teacher guided them and taught them Jewish values. The girls went together with the teacher to the Friday evening prayer service in the synagogue, which was a great novelty. When Ms. Berman the teacher left Steibtz, she was replaced by Nechamachik, a teacher from Rubzhevitz. The school existed until the outbreak of the Second World War and was closed with the arrival of the Soviets. A carpenters' cooperative was established in the school building and a tailors' cooperative was set up in the building of the Talmud Torah.

The Small Yeshiva

This yeshiva began in the early 1920s and was founded by Rabbi Yehoshua, who would give a Gemara lesson there. His brother, Rabbi Meir Lieberman– may he live long and happily, – (today in the USA) also gave a lesson there. Rabbi Simchah Plotkin – may the memory of this righteous man be blessed, excelled as head of the yeshiva and spiritual leader, and would inspire his students with his lessons and talks on ethics. Many years later, after leaving Steibtz to serve as the head of the famous Remeilis Yeshiva in Vilna, his former students would mention his name with affection and admiration. During his period of tenure, the yeshiva in Steibtz thrived, the number of students increased, and some also came from small towns nearby. These pupils were accommodated in the homes of leading members of the community and Reb Yosef Miskov took responsibility for providing their food, by arranging set “days” for them. This meant that every day, each student would have his meals at the table of one of the leading members of the community.

The yeshiva ceased functioning for several years and then reopened in 5694/1934 and remained in existence until the outbreak of the Second World War. At first, classes took place at the prayer house on Potchtova Lane and later in the prayer house in the Yurzdika neighborhood. Great Torah scholars served as teachers – the Rabbis Yehuda Kaganovitz from the small town of Derevna, Rabbi Moshe Gitteles, Rabbi Yaakov Domnitz, and Rabbi Dovid Shmuelovitz. The yeshiva thrived in this period too, and students came here from the adjacent small towns. There were four classes in the yeshiva and from here the students left to continue their studies at the yeshivot in Baranowicz, Kletzk, and others.

“The Tifferet Bachurim” Circle

In the year 5691/1931, an organization called Tifferet Bachurim[7] was established in Steibtz. Its mission was to strengthen religious values among the youth and the younger generation.

When the organization was founded, all the young people who were former yeshiva students, and remained loyal and devoted to the tradition of their forefathers, joined the group; likewise, honorable young artisans joined Tifferet Bachurim. The organization formed a fine framework for the scores of young people who set aside time for studying Torah every evening – the weekly Torah portion, the Shulchan Aruch[8], and a page of Gemara. Young people from other groups were often drawn to them. Lessons were given by Rabbi Reb Yehoshua, Rabbi Reb Yehuda Kaganovitz, and Rabbi Reb Dovid Shmuelovitz.

The group of Tifferet Bachurim was in existence in Steibtz even before the First World War, and only with the outbreak of the war was there a suspension in its activities. The Tifferet Bachurim organization had its center in Vilna, and a kibbutz hachshara[9], – and an agricultural training facility, in Pinsk. Alter Menaker from Steibtz left for this training program and introduced some innovations. However, he didn't succeed in securing an entry permit to the Land of Israel, so he remained in the Diaspora. The Tifferet Bachurim organization in Steibtz provided a loyal reserve for the branch of Agudat Yisrael[10] and they continued to exist side by side.

In the ultra-Orthodox weekly, Dos Vort[11], that was published in Vilna, issue number 355, on the eve of the Sabbath, (of the weekly Torah portion, Ekev 5691[12]), we read (in a translation from Yiddish) inter alia:

“As in other towns, an ultra-Orthodox youth organization, Tifferet Bachurim, was also established in our town on Tuesday – of the week of the reading of the Torah portions Mattot–Massei[13] by the righteous preacher of the town of Baranowicz, Rabbi Zuchovitz. Its success is greater than expected, and the organization already has 30 members – may it continue to grow! Lessons in religious studies are held every evening, and apart from the registered members, many leading members of the community and young supporters participate.

On the Sabbath Chazon[14], a youth rally was held in the Chorev school. Among the speakers at this event were, the Gaon[15] Rabbi Reb Peretz Siletzky of the Mir Yeshivah, the student, Aharon Chayat, and other members of Tifferet Bachurim. Our group (Chorev school) has a wall, on which articles and essays are displayed every week, dedicated to the goal of the organization and its mission.

All this has brought about the dissemination of the ideas of Tifferet Bachurim among wide circles in our town, that relate to it with great sympathy. Those who have done much to establish Tifferet Bachurim are the members, Reuven Tunik – secretary of the Benevolent Society and the student Aharon Chayat.

May we remember the members of Tifferet Bachurim and the Yeshiva teachers and students who were killed in the Holocaust, for the Sanctification of the Holy Name.

The members of Tifferet Bachurim who perished in the Holocaust: Rabbi Dovid Shmuelovitz, Yosef Ruditzky, Mordechai Chaikel Proshinovsky, Reuven Tunik, Leib Aharon Gruness, the brothers Shlomo and Chaim Stolovitzki, Yisrael Ruditzky, Yaakov Meir Tunik, the brothers Alter and Menachem Menaker, Chaim Ozer Izgur, Dov Rubinshtein, Moshe Mekler, Feitl Bernstein and others.

Yeshiva teachers and students who perished in the Holocaust: Rabbi Reb Yeshayahu Borishansky, Rabbi Reb Yerachmiel and his brother Menachem Leizerson, Leib Altman, Idel Bernshtein, Avraham Kapushchevski, Moshe Stolovitzki, Avraham Sapuzhnik, Henich Russak, the brothers Reuven and Isaac Ruditzky, the brothers Yaakov and Aharon Zilberman, Yaakov Moltzadsky, Yechiel Reznik and others.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Jan 2024 by LA