[Page 22]

Khone, the Prankster

In this tense atmosphere in the cheder, however, there was also fun. Among the more than twenty boys, there were four who looked like “bar-mitsve-bokherim”[1].

Our teacher called them “the four big goyim”[2]. We didn't know what they were doing in the cheder. We never saw them studying. They sat at the corner of the table by the door and talked.

Apparently, their parents had given them to the cheder so that they wouldn't roam the streets and, “kholile” [God forbid], go down a bad path...

Among these four boys was a student named Khone, who had the voice of a “khazn” [cantor], gray eyes, a red face, and a flat nose. And this Khone, according to his own words, was afraid of evil spirits. Once, when the rabbi, whom he called “Kayom”, asked him to go to the grocery store to buy something, he wouldn't go for fear of the devil.

“Rabbi,” he asked, “perhaps an evil spirit will get me?”

And a second time, when the teacher asked him to take a little boy home in the evening, Khone again refused and asked again:

“Rabbi, but maybe an evil spirit will get me?”

Many of us boys laughed a lot, but not Khone. He made a serious face, as if he believed in his own story, like a real actor...

Mordekhay Gimpl didn't laugh either, not even a smile. We never saw him smile.

Ten years later, when I met Khone on the street, he was already a tall young man. He was already in America, speaking English, and his first question to me was: “What do you think our former 'Kayom' is doing?”

I never found out

[Page 23]

how he came up with the word “Kayom” and I don't know until this day...

Translator's footnotes:

- „bar-mitsve/bar-mitzvah-bokher“: Boys at the age of 13. When a Jewish boy reaches the age of 13, he becomes a full member of the community, which is celebrated accordingly. Return

- gentiles Return

The “Rutker”

I didn't study at Mordekhay Gimpel for more than one winter term. My father knew - although he hadn't seen the cheder himself - that the melamed had too large a school. Twenty boys was simply too many for a single melamed to give each student enough attention.

In addition, the unsanitary conditions in the courtyard were simply appalling...

My former rabbi came to visit us at “khalemoyd peysekh”[1] to beg my father for mercy. He should send me to him for one more semester. He cried and complained that he was a “mekhuser-lekhem”, a needy poor man without bread. His sick child had died and he had other worries. But it didn't help him.

My father didn't want to change his decision.

And I got a new rabbi, who was known as “the Rutker”, because he came from the small shtetl “Rutke”, Łomża gubernye[2].

My new “teacher's” cheder was located in a narrow, dark alley to the left of Motl Water-Carrier's Street, in a white wooden house with upstairs rooms. The cheder, however, was not in the usual upstairs rooms with alcoves, but in a square, crooked upper room that protruded from the house and was supported by two long, rusty, square iron girders.

The “ Rutker “, a Jew in his mid-thirties, of tall stature and with a blond beard, resembled the “Choroshtsher” not only in appearance but also in his attitude toward the students. Very often we heard him say, “What fools you are!”

But like the Choroshtsher, he was wise enough not to

[Page 24]

shout at the children of the rich, among whom were Peretz Amsterdamski and Ayzik Levisnki. Today the first is called Peter Amsterdam and is a chemist, and the second is A.V. Levin, an architect.

Both have lived in Philadelphia for more than half a century.

My new melamed had a wife who could not really be described as “krasavitse” [beauty]. A plump Jewish woman with sad gray eyes in a broad face. She always wore a white bonnet. But she was not a troublesome person. She never beat her fifteen-year-old daughter, nor did she cultivate the “virtue” of the Choroshtsher's wife.

The “Rutker” also had a ten-year-old boy, Shmuelke, with a big head, black eyes, and a pale face. Shmuelke also had the weakness of begging his father's pupils for a piece of bread with chicken lard, a “gribenye”[3], or a sip of kvass.

If a pupil didn't want to share the food he had brought from home, he would beg a second time until the “stingy” pupil chased him away with the words: “ Get lost, you pale cow!”

I studied for two semesters with my third teacher. He concentrated on the “Khumesh” and the “Tanakh”. He taught us Jeremiah, Job, Mishlei, Shmuel Alef and Shmuel Bet, Melachim Alef and Melachim Bet. We also learned Shir haShirim, Kohelet [Ecclesiastes], Megillat [Book of] Ruth, Megillat Esther, Perek[4] and other contents.

He boasted that his students understood the lessons he taught them. But this was just bragging - a “melamed'ish” boast, if you will - because neither I nor the other students later became “experts” in biblical matters...

Translator's footnotes:

- Yiddish pronunciation of “Chol HaMoed Passover”: The period of time within the Passover holiday Return

- state-level administrative district (Russian) Return

- „gribenye“. I think this is “gribene”, a dish of chicken or goose skin cracklings, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gribenes Return

- A “perek”, or in Yiddish, “peyrek” is generally a section of a book from the Tanakh or Talmud.

It is possible that a subsequent word is missing here, namely what kind of book section is meant. Return

The “Vishonker”

When I left the “Rutker”, I was already nine years old, and therefore old enough to become a “Gemore-bokher”...

And I was given

[Page 25]

to a melamed who was known among the other teachers as “the Vishonker,” because he came from the small shtetl of Vishonk, Łomża gubernye.

My new rabbi was in his mid-twenties, tall and strongly built, with big, black, dreamy eyes. He was a “Gemore” [Gemara] teacher in the truest sense of the word, for he taught only the “Gemore” [Gemara] and gave no other lessons.

He began with the mesakhte [tractate] “Gittin”. Whether we nine-year-old boys really learned anything from the content of [1]“המביא גט ממדינת מעבר לים”, I don't know. But the rabbi “hot getreyet zayn best” (to use a “Yiddishized” English expression)[2].

And so he tried to instill the laws in our young minds, how a Jew is allowed to divorce his wife and when a divorce bill is “posl” or not and posl, that means “kosher”... His dreamy black eyes revealed how annoyed he was that his students had “dull minds” and did not understand the “pshat”, the interpretation of the “tnoim” [marriage contracts]. But he also suffered from another annoyance: he was angry with his father-in-law, who had promised him a dowry but had not given it. My fourth rabbi was one of those bridegrooms who were made fun of and about whom they sang:

“Ot azoy un ot azoy nart men op a khosn;

M'zogt im tsu a sakh nadn un m'git im nit keyn groshn.”[3]

In fact, his father-in-law, a Gerer[4] Hassid of tall stature, with a long, reddish-blond beard, always dressed in a well-worn kaftan, had given his son-in-law a beautiful wife, one might say a “yefas-toyer” [great beauty], but no “mezumonem” [cash] - for unfortunately he didn't have any.

Neighbors told me that he, my rabbi, had hoped to open a shop with the promised “silver” so that he wouldn't have to continue teaching. But his hopes were not fulfilled...

The Vishonker had his cheder

[Page 26]

in an upstairs room with alcoves and a window looking out onto the busy Surazer [Suraska] Street, into the houses of the “yoyreshte”[5].

The apartment was one long room. The “bedroom” was separated almost to the floor by a white sheet, as in Mordekhay Gimpl's house. The rabbi's young wife stayed in this “chamber” with her newborn daughter, who often “made herself heard”.

But her crying didn't bother us students, on the contrary, her crying brought a little cheerfulness to the tense atmosphere in the cheder...

Translator's footnotes:

- Excerpt from tractate Gittin [plural of the word “get”= bill of divorce], chapter 1, Hamevi get me'medinot me'ever la'iam, “ A person who brings a bill of divorce [from a husband to his wife] from a country overseas…“ Return

- He tried his best Return

- “This is how you make a fool of a bridegroom; promise him a large dowry and don't give him a penny.” Return

- large Hasidic community, originally from Góra Kalwaria [yiddish=“Ger”], a town in the Masovian Voivodeship Return

- yoyreshte= heiress Return

|

|

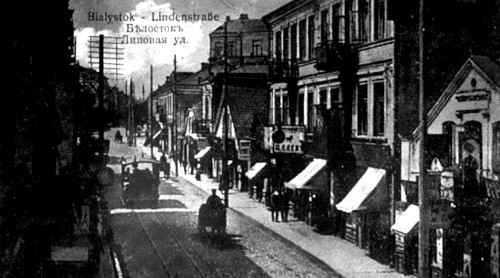

Surazer Street and the synagogue courtyard

A view from the balcony atop the Town Clock; below, length-wise, the famous Surazer Street, which once served as the starting point of the Revolution against the Czar. On the left the large Synagogue may be seen, as well as the adjoining courtyard, which was the center for the religious life of the city.

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

The Cholera in Bialystok 1891- and How I almost Drowned

If I am not mistaken, it was in 1891[1]. During the summer when I was studying with the Vishonker Gemore melamed, the cholera epidemic broke out in Bialystok (it was the second one, the first one had broken out twenty years earlier). There was a terrible panic in the city. Many people fell ill and died.

Those who somehow had the opportunity fled the city.

In the schools, however, people studied! The epidemic mainly affected the poor population living in the narrow streets around the courtyard of the shul [synagogue] and in the area of Suraska Street. The police ordered the owners of these streets to whitewash the gutters to prevent the spread of the epidemic.

Once, on a very hot day, our rabbi decided to take us to the forest to study. He, the melamed, was a Gerer Hassid like his father-in-law and wore a long black kaftan and a small cloth hat with a visor.

He led us pupils - with our Gemore's under our arms - into the forest, along some narrow

[Page 27]

and wider roads, crossing Mirtshe's and other roads, until we came to the wide Malke die sheynkerke's [innkeeper's] road, which was right at the edge of the forest. Where the forest began, there were two hills, and between these hills there was a long lake where you could bathe. This lake was known as “the second lake” because the first lake was Elye Tsitrinik's [Citrinik's] pond on the Pyaskes.

Translator's footnote:

- The outbreak of cholera in Bialystok was in 1893. Return

How I almost Drowned

As soon as we reached the water, I wanted to show my friends that I was a good swimmer. I decided to swim across the entire width of the lake. When I had swum to the middle, I realized that the “second lake” was much deeper than the first and that I was running out of strength to swim any further. I started to kick down with one foot to see if I could already feel the bottom. Then I could have stood up and rested, but I didn't step on anything. Instead of a bottom, I could only feel water and I started to sink... The water was already above my head.

Then I managed to emerge from the water. I spat out the salty water and began to swim again, searching for the bottom with my feet, but again in vain.

And I sank again, and again the water came into my mouth.

It was as the verse goes:

[1]“כי באו מים עד נפש”

But miraculously, I managed to swim ten steps from the shore, where the water was not so deep. And I was able to get up. By a hair's breadth, these lines would not have been written... For I would have been the victim of my boyish, foolish recklessness.

Neither dead nor alive, I fell on the green hill by the lake and gasped for breath. I was as pale as white paper (or so I was told at the time).

The rabbi

[Page 28]

sat with the other students a short distance from the lake and waited for me. The whole tragedy, which seemed to take forever, lasted only five minutes. When the rabbi saw that I was still not with the other students, he came to me. And I told him about the danger I had just been in. He gave me the blessing of deliverance.

After that we stopped going to the forest. Years later, when I would occasionally pass by the “second lake”, I would look in horror at the area of water where I had almost lost my young life...

Translator's footnote:

- from Psalm 69 [the so-called Prayer in Danger of Death], “[Deliver me, o God, for] the waters have reached my neck“ Return

The Free Kitchen and a Gentile Polish Woman

Becomes a Jewish Daughter

During the months when the cursed cholera raged in Bialystok, in addition to my own “experience” of crossing the lake, I witnessed a strange “incident”, if one can put it that way:

That summer, as every summer, Jewish university students came to town on vacation - the future doctors, lawyers, engineers, chemists, dentists, and other professionals.

This group had decided to do as much as they could to improve the bitter situation of the people suffering from the epidemic. They persuaded the rich and powerful of the city to open a free “kitchen” where the poor, both Jewish and non-Jewish, could get a full and healthy meal at least once a day in order to become resistant to the attacks of the dangerous cholera bacteria.

They opened the free kitchen in an alley across from the large shul [synagogue]. Unfortunately, I don't remember the name of the alley.

[Page 29]

I only remember that the alley was lined on both sides with one- and two-story dark wooden houses and a few red “moyerlekh”[1]. In an open window of one of these brick buildings, two students in their uniforms were handing out slips of paper, i.e. tickets, to enter the large dining hall across the street.

I was interested to see how the free kitchen “worked”. So I took my schoolmate Yudl Finkelshteyn, the son of Velvl the vapnik [limeburner?], and we both went to see how the hungry ate there at noon. We had already eaten at home.

When we got to the door, one of the “gaboyem” [charity overseers], a slender Jew with a short black beard, invited us to enter the hall to eat with the hungry men, women, and children.

We were reluctant to go in, thinking that it was not appropriate for “balebatishe” children to sit and eat with the poor. But the good-natured charity overseer just dragged us in...and we had to eat too...

There were about two hundred people in the large hall. The July sun shone brightly into the building from three sides, and the atmosphere was like that of a wedding...

The meal consisted of a bowl of barley soup with diced meat. There was also bread and tea, of course. After we had finished the meal, which is called “beef stew” here in America, a strange incident occurred that really amazed everyone present:

From a bench almost opposite us, a middle-aged woman with dark brown, gentle eyes suddenly stood up and shouted in Yiddish:

“Jews! I am a Catholic, Polish peasant. Now I want to become a Jewish daughter, a Jewess!”

She paused for a moment and continued:

[Page 30]

“Just look, see what the Jews do for their own kind and for our needy brethren. Do “my” Christians do the same? Certainly not!”

As the sated crowd began to disperse, the two charity supervisors approached the Yiddish-speaking Polish woman and, as required by [Jewish] law, tried to dissuade her from changing her religion. But she insisted on carrying out her wish. And so, on the second day, she was taken to see Rabbi Chaim Hertz.

When I left the great hall, I heard a middle-aged, blue-eyed non-Jewish Pole say to another: “Yak ona khtse bitsh zhidovka, to niekh ona bendzhe” (If she wants to become one of the Jews, she should become one).

Translator's footnote:

- moyerlekh= Wall or a building made from brick or cement Return

My Certificates and the “Korelitser”

At the end of the summer, a few weeks before the “Yomim Neroim”[1], the cholera epidemic subsided somewhat and there were no more reports of deaths caused by the terrible disease. The municipal doctor issued an order that the population should not eat cucumbers. And the next day there were piles of the forbidden food in the courtyards.

After Sukkot, I stopped going to the Vishonker. “He's been going to cheder long enough,” my father said. He himself was not pious. If the “shabes-goy”[2] didn't come to heat the oven and prepare the samovar, he became the “shabes-goy” himself. My unobservant father once claimed to my very observant mother - the daughter of a Kotsker[3] Hasid from Krynki - that I had already learned enough Judaism:

“Why does he still need the cheder?” he argued with my mother, “he can already read a prayer book well, 'mayver-sedre zayn'[4], recite the Haftarah portion as a 'mafter'[5], say Kiddush, so what more does he need? He's not going to be a rabbi anyway, and I don't want him

[Page 31]

to be a rabbi. We already have enough “noble impoverished people” in the family. However, my God-fearing mother, who fasted every Thursday, was afraid that once I stopped going to the cheder and started going to [regular] school, I would have to sit without a head covering and, G-d forbid, even eat without [the ritual] washing [of the hands] and the blessing...

So she protested strongly against taking me out of the cheder. But my father decided otherwise and sent me to Yofe's school, the “Yevreyskoye natshalnoye utshilishtshe,” where Ilya Davidovitsh Yofe, an assimilated Jew from Vilnius, worked as a “zavyedyvayushty” (administrator).

Therefore, the only state educational institution for Jews in the city was called “Yofe's School”, and every student of this school was considered a “Yofist”.

Early one morning on “khalemoyd”, I went with my father, who spoke Russian, to the uprave (city magistrate), got my certificates, and went to Yofe's school, which was on the same New Town street, to enroll. Yofe, the head administrator, a tall, compact man with a round brown beard and large round gray eyes behind gold spectacles, read my birth certificate and determined that I was too young for the class I was supposed to be in. He explained that since I could already read and write a little Russian (which my older sister had taught me), he couldn't put me to the “prigotovishkes” (beginners). So I would have to wait a whole year before I could go to the higher class.

Needless to say, Yofe's message was a great blow to me. When we got home, I was very sad.

It had become a serious problem for me and my parents: What to do now? Now that neither cheder nor school was an option –

[Page 32]

what then? Sitting at home made no sense either. My father wasn't able to hire a teacher for me.

A few days later, however, the problem was solved. My father happened to meet an old good friend, Todl Segal, who was also a small factory owner and had the same problem: his son, Shiye, was also unable to go to Yofe's school because of his age. So as not to leave him at home, he gave him to a melamed for the time being.

My father followed his friend's example, and I was lucky enough to get a new rabbi, the “Korelitser”.

My new melamed was known as the “Korelitser” because he came from the small shtetl of Korelits, Vilnius gubernye. He was a Jew in his fifties, with a broad black and gray beard, glasses, and used to boast that he had once been a merchant in his hometown of Korelits.

But when his business went bankrupt, he was forced to devote himself to Jewish scholarship. He became a “good” Gemore teacher in our town.

His cheder was located in a dark two-story wooden house at the back of a courtyard on the wide Povitshizne, directly opposite the “Sobor” (Russian Church). This was a white-painted, imposing building with wings that reached out to the wide Nowolipie, and with a huge “kolokol” (bell) that sometimes rang so loudly that it could have made you deaf. It disturbed our studies...

Translator's footnotes:

- Yiddish version of Yamim-noraim, the Days of Awe Return

- Non-Jew who performs the domestic tasks that are forbidden to a Jew on Shabbat Return

- see https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menachem_Mendel_von_Kotzk Return

- to re-read the sedre of the week with emphasis Return

- Yiddish version of „maftir“, the person who recites the last reading of the Torah, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maftir Return

|

|

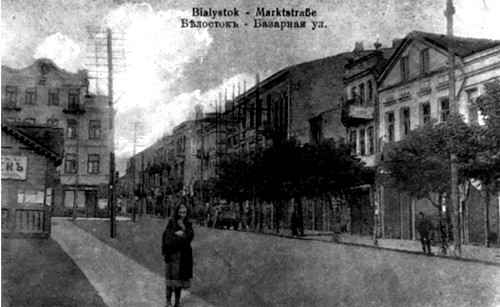

Bialystok, Nowolipie Street

The beginning of Nowolipie Street, at the King's Gate – From the Railroad Station, one arrives at the beginning of Nowolipie Street, where, till the war, stood the King's gate, erected in 1897. Nowolipie Street led directly to the center of the city. On both sides of the street were some of the finest structures of the city as well as many public buildings.

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

|

|

Wąskie Nowolipie

Narrow Nowolipie – was the principal commercial center. Here was the famous Woroshilsky jewelry store, where many young couples came to purchase their wedding rings.

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

|

|

Koniec Nowolipia

The end of Nowolipie – quartered many other well-known shops in Bialystok

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

Shnayim Ochzin Be-Tallit[1] and Shor She'nagach et Hapera[2]

My new (and second) Gemore-melamed chose as the theme for us two sections: [1] שנים אוחזין בטלית from the Talmudic tractate “Bava Metzi'ah” and [2] שור שנגח את הפרה from “Bava Kamma”.

[Page 33]

The Korelitser “ongekarelitsivet”[3] us so much with his two sections that it was already hanging out of our throats. “Shnayim ochzin be-tallit” - he explained to us - is when two Jews find a tallit [prayer shawl] and each of them thinks that the find belongs to him alone.

According to Jewish law, two people who find something must share the find (יחלוקו)[4]. But if it is a tallit, you cannot tear it in two without depriving it of its function. Well, well, - and a disagreement, פּלוגתא had already arisen.

We students discussed this question among ourselves: Since the two Jews went together and both found the tallit, what right did each of them have to claim the find for themselves? Another student asked: Since you can't split up a tallit, would it be “legal” for the two of them to sell the object and share the money?

No one was able to answer these two difficult questions.

But no one dared to ask the rabbi either.

Well, dear reader, to this day I still don't know how the conflict between the two ended over the tallit they found.

The Korelitser also bored us with the “Shor she'nagach et ha'perach” (an ox attacking a cow).

The whole “subject matter” really touched our hearts (...).

And so we waited impatiently for the end of the winter semester. The atmosphere in the cheder was also very oppressive. The rabbis' hungry children were begging from the students. Once I saw two girls standing around their father as he ate his meaty meal, shouting:

“Mat, mat!” (instead of “meat”)[5], but their father pretended not to see or hear anything. After all, he needed his portion of meat to cram into the “incomprehensible minds” of his pupils the “important” topics of the two Jews who had found a tallit, and

[Page 34]

and the ox that had attacked a cow…

And the appallingly unsanitary conditions in the yard with the open privies were simply unbearable...

In short, we breathed a sigh of relief when the rabbi announced a few days before Passover that the semester was over.

Translator's footnotes:

- שנים אוחזין בטלית= shnayim ochzin be-tallit Return

- שור שנגח את הפרה = shor she'nagach et ha'pera Return

- A humorous word creation by the author, in which he transforms the name “Korelitser” into a verb. Return

- יחלוקו, yachloku= they should divide Return

- The children literally said “feysh, feysh” instead of “fleysh” [=meat] Return

The Conversion Epidemic in Bialystok

During the few semesters that I had studied with the “Vishonker” and the “Korelitser”, two great events occurred in Bialystok that really shook the whole city.

One winter day it was announced that the only daughter of a prominent businessman, Khaykl Grave, from Gumienna Street, had converted and married the municipal doctor Glovatski. And a few months later the whole city was astonished again when it was learned that Reyzel, the beautiful and educated daughter of the “moykher-sforim” [lover of Jewish books] Tykotshinski [Tykoczinsky] on Khaye Odem Street, had also converted and fled together with the “starshi gorodovoy” [chief officer] of Pyaskes and Sukhazer [Suraska?] Streets. He was tall, brunette, with two black evil eyes, poorly educated, and a strict policeman, nicknamed “Cossack”. (He was really a Cossack and not a Bialystoker).

As I said, Reyzele's conversion was a painful experience. No one could imagine that a beautiful and educated daughter of a Jew who sold seyfer-toyrim [Torah scrolls], as well as khumoshim [Pentateuch], sidurim [prayer books], makhzoyrim [prayer books for the high Jewish holidays], tefillin [phylacteries], tallits, shofars, parokhes [curtains in front of the Torah shrine], bone-made pointers for teachers, and other religious makhsirim [utensils] - such a Jewish daughter should adopt the Orthodox faith and flee the city with an almost illiterate, lousy, unlikable goy! ?

[Page 35]

The two conversions were talked about for a long time. Everyone asked, “Where did Reyzele actually meet the 'Cossack'? Where did he go, and where did she go, and where could they have met?”

Well, it was said that Khaykl Grave's daughter had met Doctor Glovatsky at the “Vetsherinskes” in the house of the assimilated Jewish lawyer Fridberg in “New Town”. But where had “Madmoiselle” Tykoczinsky met her “future husband”?

That remained a mystery forever.

The tragedy in the Tykoczinsky family naturally hit the parents and their other children hard. Father and mother sat shiva, as is customary, and during the week the rumor even spread that the old man had committed suicide. People sympathized with the moykher-sforim's family. Therefore, his shop was not boycotted. On the contrary, people bought not only things they needed, but also things they didn't need in order to somehow comfort the parents.

But no one took pity on Khaykel Grave. He was a “miserly gvir[1], ” did not give to any charity, and did not show his face anywhere. Four years later, his converted daughter suffered a great misfortune: her husband, Dr. Glovadski, died. But she could not return to her parents, and the Orthodox Church would not allow her to become a Jew again. She remained “vi oyfn vaser”...[2]

Translator's footnotes:

- gvir= a powerful, rich, distinguished man Return

- literally, “as if on water”, meaning that she remained alone, cut off from her family and her religious roots Return

|

|

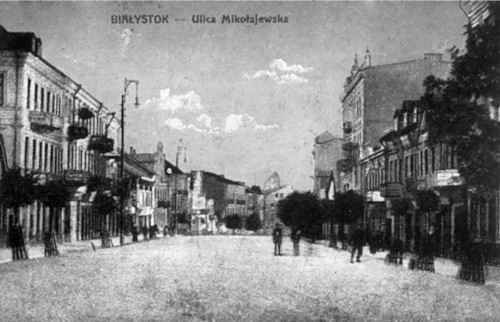

| Gumienna Street

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

The Drama and the Song

A group of Russian-speaking Jewish intellectuals decided to commemorate the events connected with the two conversions and wrote a drama together under the name: “Sila Predrasudka” (The Power of Prejudice).

I didn't know what the

[Page 36]

drama was about. I only saw the flyer that my sister brought home. However, the police forbade the performance of the play, and it is still not known what happened to the manuscript.

Some joker wrote a song about the converted Reyzele Tykoczinsky, which was sung by little girls:

“Reyzele, Reyzele, kum, kum tsurik,

Kh'vel dir geben a sakh nadn,

Un a sheynem yungen man”.

“Reyzele, Reyzele, come back,

I want to give you a big dowry,

and a handsome young man.”

On “my” Pyaskes, that is, the long Pyaskes, there were quite a number of male and female “meshumodim” [Jews who had converted] in those years.

Two former Jews with long white beards, dressed like beggars, roamed the streets trying to turn the Pyaskover Jews into “goyim”...

On market day, they made their living by going around to the farmers who had come in and begging them for a piece of brown bread, a few potatoes, a bit of cheese, or a piece of pork.

There were “Jews” hanging around with certain badges. They were converts who had taken positions in the government. They used to roam the streets cheekily, and when they saw a box or a chair next to a shop, they threw it away with their foot and shouted: “Nem tsu!”[1]

One of these “noble” converts with a badge on his hat, a lad in his early forties with a brown beard and a bulbous nose, liked to rip the hats off the heads of elderly Jews who didn't want to stand with their heads uncovered when a Christian funeral procession passed by.

But Bialystok Jewry regained some of the “deficits” it had lost in the course of the “conversion plague”. In addition to the Christian Polish woman who had made a “religious speech” in the Jewish free kitchen, a Russian, a compact man

[Page 37]

of about forty with a thick brown moustache, also adopted the Jewish faith. He had settled on the long Pyaskes and waited a few weeks. He was seen going in and out of the house of Aba the melamed, where he had serious conversations with him- my former rabbi.

We boys knew from the conversations we overheard that the “goy” was waiting to have “the operation” performed in secret that would enable him to become a full member of our “Akheynu-bney-Yisroel” [Jewish brothers].

Gradually, Jews and converts learned to live together in peace. The Jews who had adopted another faith came to the Jewish shops and gave something to redeem[2]. The converts no longer tried to turn the Jews into “goyim,” and the Jews no longer punished the “apostates” for leaving Judaism and converting to the Christian faith.

A middle-aged convert, tall and with a thin gray beard, used to come to our house. His name was Yakov Shor, and he came from the Kiev gubernye. He was a policeman, first in a small shtetl in the Syedlyitser[3] gubernye, and later in Bialystok.

His wife, a Polish Christian, was a laundress. He used to come to us to take the [dirty] “gret” [laundry] with him and bring it back cleaned. As a result of these two “business” visits, he usually spent several minutes talking to us. Once our neighbor asked him: “How is it possible that Jesus was born without a father?”

The “old meshumed”[4] - as the people on the street called him - immediately replied:

[5]“על הסלע הך ויוצא מים” (When Moyshe struck the rock with his stick, water came out). And seriously he remarked: “If that was possible, why shouldn't it be possible in the case of my 'Redeemer'?”

The “laundryman” Yakov Shor also recounted an interesting conversation he had with a “sudya”, a judge in a small shtetl.

The policeman, Shor, complained

[Page 38]

to the judge that there were too many “gvirim” [rich and noble] in the shtetl.

“Moltshi! (Silence!),” said the judge, “if it weren't for the gvirim, you and I would have already croaked of hunger!”...

Translator's footnotes:

- Take it! Return

- „zey flegn gebn tsu leyzn“, an ambiguous sentence Return

- probably today's Siedliszce Return

- the old Jew who had adopted a different faith Return

- Al Hasela Hoch Vayeitz'u Moyim- he struck the rock and there streamed forth water Return

Two Prominent Jews are Sentenced

to Siberia and to Prison

Two or three years after the “conversion plague”, the whole of Bialystok was again shaken by two sensational events: two prominent Jewish “gvirim” were found guilty of two very serious crimes.

The first, Leon Markus, a wealthy businessman from Vashlikover Street, was sentenced to five years in Siberia for whipping his maid, whom he had accused of stealing silver valuables from his house. However, she refused to confess.

In the highest court of the Vilnius Governorate, called “Sudyebnaya Palata” [Chamber of Justice], it was proved by witnesses that Markus had whipped the poor, unfortunate girl while a feldsher stood by and felt her pulse to determine how many more blows her body could withstand...

The “Markus Trial”, or “Dyelo Markusa” in Russian, which took place in Bialystok, lasted a full three weeks. The defendant, Markus, had brought the two most important Jewish lawyers - Gruzenberg and Shlosberg from Petersburg - who managed to convince the judges to give the defendant only a light sentence. In fact, he received a mild sentence - five years of “Volnoye Posyelyenye” (free settlement) in Siberia.

The outcome of the sensational trial was long discussed in the city. Opinions were divided. The shameless sycophants of the “gvirish” ruling system, who believed that a gvir could and should commit the greatest of crimes without fear of sanction from the guardians of the law or public opinion,

[Page 39]

took pity on the brutal gvir and gave the unfortunate maid a bad name. “Because of such a person”, they were angry, “two people have to die”...(the feldsher was sentenced to two to three years in prison).

Others, however, who had a sense of justice, argued that deporting him to Siberia for five years was no punishment at all. He deserved eternal imprisonment for his heinous crime.

There was also talk in town that Markus had suffered no financial loss from his crime. He did big business in Siberia and became even richer. But he never came back to Bialystok.

|

|

| Vashlikover Street

Source: http://wirtualnie.lomza.pl/wirtualnie/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ksi%C4%99ga-album-pami%C4%99ci-gminy-%C5%BCydowskiej-w-Bia%C5%82ymstoku-cz%C4%99%C5%9B%C4%87-1.pdf |

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

My Childhood Years in the Pyaskes

My Childhood Years in the Pyaskes

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Mar 2024 by LA