|

|

|

[Page 160]

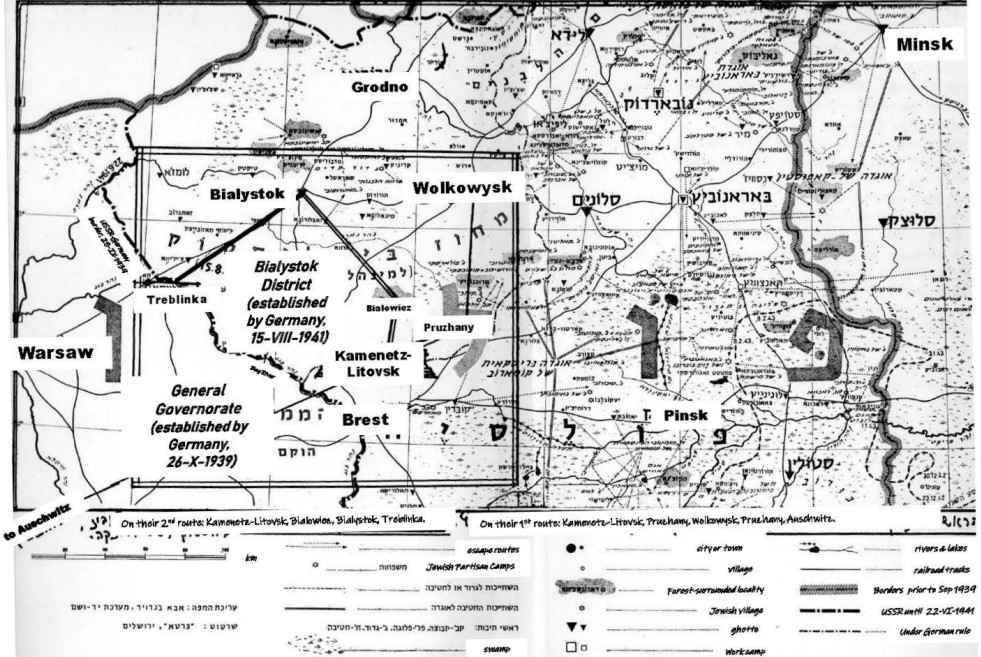

Map of Routes

Translated by Allen Flusberg

|

Footnote

By Arye Sarid

Translated by Allen Flusberg

| As the axe swung over my father's head I didn't cry out: Father! Oh, Father, alas! In the forests of Bialowież rhinos[2] then meandered Within the preserve guarded by watchmen.

As my sister and brother cried out and wailed

While my dear ones were loaded onto the wagon—

…Then my mother dragged her wounded wing |

Footnotes

By Dora Galperin

Translated by Allen Flusberg

(Based on letters to Leah and Dov Aloni; Translation [into Hebrew] by Leah Aloni-Bobrowski)

Note by translator: an English translation of the Yiddish article this Hebrew translation was based on appears on pp. 91-104 of the English section of this Yizkor Book, “The Tragedy and Destruction of Kamenetz”, by Dora Galperin. The English translation appears to be based on both the Yiddish original and the Hebrew translation.

Footnote

By Dvora Rudnitzky-Singer (New York)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

Note by translator: the original Yizkor Book contains 3 versions of this article: the first in Yiddish (pp. 540-549); a translation of the Yiddish into Hebrew by Leah Aloni-Bobrowski (the present article, pp. 174-182); and an English version (pp. 105-116 of the English section). The three versions are essentially identical. One discrepancy is the date on which the 3rd transport from Pruzhany arrived at Auschwitz. According to the Yiddish version (p. 544) and the Hebrew version (p. 177), it was February 23, 1943; the English version (p. 110) gives the date as February 3, 1943.This article may be read in the original English version on pp. 105-116 of the English section.

Footnote

[Pages 183-188]

by Yitzhak Portnoy, Kfar Saba

Translated by Allen Flusberg

Note by translator: This Hebrew–language version is a translation of the Yiddish–language article entitled “From the Ghettos to the Concentration Camps”, by Yitzhak Portnoy, pp. 534–549. Minor differences between the two articles have been noted in footnotes of the English translation of the Yiddish.

Footnote

by Leah Aloni-Bobrowski (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

(Based on Testimony by Witnesses)

Night, darkness; the shadow of death, silence. By bad luck, the first Nazi shell struck and went through the window of the house belonging to one of my students, Chaya'ke Horowitz, killing her on the spot, while she slept. Chaya'ke is gone.

At dawn the calamity became known throughout our entire town. Family members, close friends and neighbors gathered together and came, standing in grief, as fright and terror enveloped the house. They were trembling and weeping, crying and shaking, and the tears were tears of bitterness.

“If only we would have died in your place, our young child, the first victim. How fortunate for you that your death spared you from all the torment awaiting each and every one of us, our daughters, our little children and infants—may your memory be a blessing.” This was how everyone lamented her.

And with their arrival the chapter of Nazi torture began, a torment that was well planned: robbery and looting wherever they could, and in addition beatings with clubs and whips—not discriminating by gender or age—meted out to young and old, women and children, the ill and the dying.

The “first roundup”: about one hundred men were seized in the streets of the town for hard labor. The names of only a small number of them are known to us, as follows:

R. Avraham Stempanitzki, an elderly man, age 83 (the uncle of Fishka Cohen from Fijja[2], near Petah-Tikva); Chaim Yoffe, a 15-year-old boy, son of Tamar and Moshe; R.[3] Yitzhak Leib Stempanitzki, a modest man, 55 years old (the brother of Elchanan Stempanitzki from Fijja, near Petah-Tikva); R. Shalom Galprin, a man who all his life faithfully attended to community needs (the cousin of Simcha Dubiner of Petah-Tikva); Shlomo Mandelblat, the secretary of the town, an enlightened, cultured person who was well liked, good looking, and well-dressed when he appeared in public; R. Shimon Buchalter, the brother-in-law of Yosef Vigutov. May their memory be sacred to all of us.

Pruska Forest, located on the outskirts of our town, was a meeting place for the young people; in the shade of the trees they would get together, one group here and another there, to share “secrets” of their lives as they looked ahead to their future plans, some this way and some that way…

[Page 190]

Sometimes I used to come to this forest with students of the school and with my teacher colleagues. During the “Days of Omer”[4] we would go there with “bows and arrows”[5], and we would tell our students at length about the miracles, heroic acts, salvation and battles that took place in those days and at this time. We would rouse their spirits for Zion, a longing for redemption of the “land that our ancestors desired”…

And this time the first one hundred men were brought to this forest, where they were all murdered by the defiled Nazis.

And what did the foul Nazis do with the bodies of our martyrs after this cruel, atrocious massacre? Were they buried in a common grave? Were they burned? Where? Only the birch and pine, the mute, eternal trees of the forest—they are the only ones who know…

After the “first shell” and the “first roundup”, the accursed Nazis began to become even more savage. They created an atmosphere of fear in the town and all around it; they continued to rob in any way that occurred to them; and they systematically starved the people by reducing the available vital food. They set trained dogs on every passerby, and they seized townspeople day and night and put them to death with no rhyme or reason. This endless savagery lasted a very, very long time.

And on one of those black days the Nazis announced their command to our townspeople: “The Jews are ordered to leave Kamenetz-Litovsk and go to the ghetto of Pruzhany.”[6] Without uttering a single word some of the Jews left, accompanied by the Nazi beasts of prey, who treated them with horrific cruelty along the entire way.

The brilliant rabbi Reuven Burstein[7] (the brother of the prodigy of Tavrig[8]) came along with all of them, he and the members of his family as well as those attached to him, his congregation.

When they reached the ghetto many of them had been beaten and were wounded. They were hungry and thirsty, exhausted, barely alive.

It was very crowded. People being transferred from nearby towns were arriving from morning to evening. These people were broken and crushed and had nothing. Many were brought on stretchers; sickness was breaking out left and right. The food shortage kept getting worse.

The Pruzhany residents did all they could to make things easier for their refugee brethren. But with the increase in population of the ghetto and the worsening situation of the Pruzhany residents, they reached a state of helplessness in a matter of days—to their great sorrow and grief.

In these days of trouble and hardship, the esteemed, faithful and dedicated town rabbi, Rabbi Burstein, did much for his congregation. He organized multiple groups to study Torah and Aggadah[9]; with this action he endeavored to make his congregants forget their troubles, if only for a little while. People who had arrived from other towns also joined them, coming to listen to words of Torah, to obtain encouragement and strength from these “clandestine meetings”.

And on one of these terrible days, about 250 men were seized in the streets of the ghetto and sent to work on fortifications in Slovakia. Among them were a few dozen people from Kamenetz. Those left behind waited in vain for their return; all of them were put to death there.

[Page 191]

In the end some tried to leave the Pruzhany ghetto to return to Kamenetz, to live again “in der aygener haym”[10]. The “loyal guards” among the Nazis clandestinely were given “gifts”, redemption money from anyone who desired, and so they allowed people to go back to Kamenetz when no one was looking.

But then came the last act of fury—a decree that descended on them quickly.

And the bitter, black day arrived. The impure Nazis had decided to liquidate the remnant of the fugitives, come what may. One bright day, in the light of the rising sun, farmers from the surrounding area were rushed to our town with their wagons, and the final command rained down on the heads of all our townspeople, young and old, children and infants: “Jews! You must appear immediately in the town square! No one may remain in his house! The ill and little ones will be transported in the wagons. Those who hide will be shot in their hiding places. Come immediately and leave!” And thus the Jews were taken out of the ghetto.

Everyone understood that this time there was no escape. Those who were dear to us came and gathered to leave the town, following the order, as they were surrounded by the S.S. soldiers. There was no one to save them, no one to rescue them.

The Christians residents of the area were eyewitnesses to this atrocity. We know of the death march from a Christian woman who recounted that when my father, Avraham, passed by the onlookers who had gathered around, he proudly proclaimed: “Tremble with fear! Our sons and daughters in the Land of Israel will avenge our spilled blood!”[11]

From Kamenetz they were brought along the direction of Visoko-Litovsk[12], to the Bialowiec forest (where many died of starvation). All the rest were brought to Bialystok, to Treblinka[13], where they were murdered and annihilated.

The Jews in the Pruzhany Ghetto were transported to Auschwitz. Among them were people from Kamenetz, with Rabbi Reuven Burstein and his family at their head. All of them perished in the gas chambers. The entire community of Kamenetz, including its great ones and its holy people, all the members of our families and our dear ones, perished and are no more, gone forever.

May the memory of our townspeople remain hallowed in all of our hearts; may their souls be bound in the bond of eternity and of our tears, together with the tears of the entire ancient House of Israel.

Yitgadal veyitkadash shemay rabba![14]

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kamenets, Belarus

Kamenets, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 1 Jan 2022 by LA