|

|

|

[Page 21]

Beginnings of the Town Kamenetz–Litowsk

By Levi Sarid (Laybl Goldberg)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

The beginning of Kamenetz–Litowsk occurred in the Middle Ages, during the period of the dawn of nations and states that burst on the scene among wildly overgrown roads, forests, muddy swamps, rocky wildernesses and broad wild plains.

This town that we knew—in the hinterland, far from the railroad line—is actually crowned with an ancient, eventful history. In its early years it was a central city whose founders apparently anticipated great things from it. But from the beginning of the 18th century, its star began to dim, and it remained a typical town that preserved its essence and form like other towns of Lithuania of our period, still stuck in the world and tradition of the Middle Ages. So, too, has it been preserved in our memories—we of the last generation of its Jewish residents.

Few among its natives who are today dispersed throughout the world know that this town—with its dilapidated cottages, suspended here and there on cliffs; with its rows of miserable shops that were built like cages—had also experienced a splendid past, in the shadows of kings and princes. From a historical perspective Kamenetz–Litowsk appears as a major city on the central crossroads of Poland–Lithuania, leading from the far north of the State of Poland–Vilna and its surroundings—to its south, bustling with life and international trade. It provided protection and defense to the important central city of that time–Brest–Litowsk[2], which served as an essential hub of continental trade with the East. Brest was a vital intersection in the trade routes between distant countries and states. From it the roads branched out to the inner states that made up ancient Poland: the Polish Crown, Ukraine, Russia and Lithuania.

[Page 22]

The Chronicles tell of the establishment of the city in the year 1276. They explain that the city of Kamenetz was established for the security needs of Brest–Litowsk, which the Lithuanian and Russian tribes were fighting over. This opinion is expressed{i}{ii} by Latkowski, the historian of ancient Lithuania. From the document cited by Latkowski concerning the war between the Lithuanians and the Romanovyches[3] before the ascension of Poland–Lithuania, the place Kamenetz is depicted as one of the strategic points over which a fierce battle was fought in 1262. According to this document, Mendog[4] sent an army that fought near Melnic and Kamenetz. Latkowski identifies these places with Mielnik in Podlachia[5] and Kamenetz–Litowsk{iii}.

The association between these places occurs about one hundred years later, when Janusz the prince of Masovia[6], who was the son–in–law of Kistut [Kęstutis], conquered the cities Drochitzin [Drohiczyn] (Podolski)[7], Suraż[8], Melnic and Kamenetz.

The historian of the Kobryn area, Severin Wisołuch{iv}, who was descended from the Lithuanian szlachta [nobility], rejects the opinion of Latkowski, and strongly expresses the opinion that Kamenetz refers to Kamin Kashyrskyi[9], on the border of Polszia–Poland. But it appears that Latkowski is right that the ancient battle was concentrated in the areas of Podlachia, and it can be assumed that Kamenetz was the name of a village in that area, on whose foundations the city was built.

According to the chronicles known to us from the archives of the Volyn[10] principality, the founder of the city of Kamenetz was Vladimir Vaselewicz, the ruler of Volyn, who resided at that time in Brest. He was also called the philosopher, and was the ruler of Vladimir Volynsk[11] (Ludmir). The chronicle recounts: After Brest was destroyed by the Tatars (apparently, during their second invasion in 1259), it was decided to establish a line of fortifications that would protect Brest from the hinterland. It should not be forgotten that the 13th century was renowned as the period in which urban settlements of Poland and Lithuania were established, and thus this document may perhaps be viewed as an additional source for the establishment of the city.

In 1276 Vladimir sent his officer Oleszko to find a suitable location for the establishment of a fortified city. After the latter had located the designated place, Vladimir, too, arrived with his retinue—a group of Boyars[12], young nobles from Brest—and he set up his headquarters there. According to the above chronicles, they chose a rocky peak on the banks of the Leshna River, which is referred to in all the sources as Greater Leshna{v}. They immediately began to clear the thick forests that surrounded the peak, and the city called Kamenetz thus began its existence in 1276.

To defend against attacks by the Tatars (the last attack by the Tatars was in 1287, and it was blocked by the Poles near Krakow[13]), they began constructing a large fortress, which is known to us as the “Slup”{vi}. Once it was completed its height reached 37 meters (17 sazhen[14]), and its circumference 35 meters (16 sazhen). Within the fortress they arranged oak stairs, which, remarkably, have resisted rot and destruction to this very day. They constructed openings in the walls of the fortress tower for firearms barrels, and similarly they built a system of canals that led to the river, so that supplies and men could be conveyed to the tower. The fortress is referred to as the “White Fortress”{vii}. In medieval times the word for fortress was locally pronounced “ordos”{viii}, which denoted fortress in Latin. The surrounding forests were also afterwards called “the forests of the White Fortress”, and from this is derived also the name of the forests of Bialowieza[15], after the name of the fortress of Kamenetz.

It should be noted that the forests of Kamenetz and Bialowiez are mentioned side–by–side in the above chronicles. An official empowered by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, whose domain was over the Bialowiez and Kamenetz wilderness, was appointed over them both. During some periods the permanent residence of this high official was located in Kamenetz (e.g. Philip Machewicz at the end of the 16th century, who was called the woodsman of the forests of Bialowiez and Kamenetz){ix}.

[Page 23]

Kamenetz is denoted by two different names in the sources from the 14th century: Ruthenian Kamenetz{x} and Volynian Kamenetz{xi}. For those who are not well–versed in the history of Poland and Lithuania—it should also be pointed out that in the first few centuries of the second millennium, Volyn was an integral part of Lithuania; it was detached from it only after it was annexed to the Polish Crown before the unification of Lithuania and Poland{xii} in 1569[16]. Kamenetz was connected to Volyn by the main highway that led from Vilna to Lvov[17] and passed through the province Masovia on the west and the area to the east of Narew[18], known in the ancient history of Poland as the place of “the Great Swamps”. The important crossroad was Novyi Dvor[19]. In the 16th century this road was called the Great Highway{xiii}; and from there [Novyi Dvor] the path continued west to Pruzhany[20], Szereszew[21] —which was then part of the province of Kamenetz{xiv} —and from Kamenetz the road continued on to Brest, then to Lubomil[22], and from Lubomil to Red Russia and to its capital, Lvov.

Kamenetz was annexed to the Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century, and was the capital of a province that bore its name; this was a large starostwo[23], whose eastern border was the province of Kobryn (then the duchy of Kobryn), with Pruzhany on the north. According to a document dated April 26, 1380, Witold[24]{xv} transferred the village of Szereszowa [Szereszew or Šarašova, see above] to his friend Mikolai Nasut Szampert. The Nasut family was a dynasty of dukes who greatly influenced Jagiello, and Szereszowa appears here as an estate that was located within the domain of Kamenetz{xvi}. After Gedimin[25], the founder of Greater Lithuania, was wounded in the Battle of Wielowa, during the war against the Saxon Knights, he bequeathed his estate to his seven sons; and Kamenetz and its surroundings went to his second son Kiestut[26]{xvii}. During his reign the attacks by the Teutonic Knights reached their climax. The first attack by the Teutons on Kamenetz occurred in 1375, under the leadership of the Belgian Komtur [Commander] Theodor von Elsner. The Chronicle mentions the abundance of spoils that Theodoric took in captives, cattle and horses. In this battle Kamenetz was badly damaged, but the Teutons were unable to conquer it; they did not destroy this important strategic location. In the intense attacks that were repeated in 1319 they took the city and held it for a short time, but at the end of that year they were forced to retreat from it{xviii}.

[Page 24]

During the period of the war of inheritance between the brothers Kiestut and Jagiello, Janusz the prince of Masovia, who was the son–in–law of Kiestut, conquered the city of Drohiczin, Melnik and Suraż, and finally Kamenetz, which was, according to the claim of Janusz, included in the dowry of his wife Danuta, who was Kiestut's daughter. It may be assumed that Janusz reached Kamenetz along the above–mentioned “Great Highway”. Jagiello then lay siege to Kamenetz in 1383; and after conquering the fortress and the city, he stayed there for a while. According to the treaty between him and Witold, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Kamenetz was transferred to Witold as a possession, and starting then (1384) it was incorporated into the Duchy of Lithuania. As a part of the Brisk region, Kamenetz had fallen into the possession of Witold as an inheritance from his father Kiestut. (At that time Witold also obtained Grodno[27]; and in 1388, four years after the treaty, he provided the Jews of Brisk with the first charter of their rights).

After Witold conquered Kamenetz, it became a central location within the entire region, and together with Brisk and Kobryn it was considered an important provincial capital of Lithuania. Indeed, this is how they are depicted in the documents from that period. Its location on the main highway from Krakow to Vilna and its envelopment by the forests of Lithuania gave it a unique value. For this reason, we see that from the 15th to the 17th century it served as a meeting place for the king's council, particularly in the summer season. These council meetings were accompanied by royal hunting excursions that the king and the Lithuanian nobility participated in. It was in Kamenetz that the historic meeting between Pope Alexander V's emissary and Jagiello and Witold took place. This meeting occurred during the great papal schism[28] between Gregory XII, Benedict XIII and Alexander V. Alexander's legatus (emissary) came to Kamenetz to ask Jagiello, who was then living in the city, to have Poland and Lithuania join his camp, which supported the unification of the Catholic Church that was then split between the three popes.

It was also here in Kamenetz that Casimir of Jagiellon[29] spent some of his time while he was heir to the throne and Grand Duke of Lithuania{xix}. During his many journeys within Lithuania he spent time in Kamenetz. When he was also the king of Poland, he would conduct council meetings there with the Polish nobility, and, accompanied by the noblemen, he would of course go on hunting excursions.

For some time Kamenetz was withdrawn from the Brisk region and was instead annexed to Podlachia[30]. But in 1569 the city was returned to the Brisk district, and since then this situation has not changed. As stated above, Kamenetz was a starostwo [administrative unit] and was considered a royal possession. In 1525 Kamenetz was granted the status of a voivodeship[31]{xx}{xxi}{xxii}. This status provided it with rights, in addition to the Magdeburg Rights[32] that apparently had been granted it—together with Brisk, Grodno and other cities—in 1496. The administration of the city was thereby extended, and the Woit [bailiff] served as a chief municipal judge; and from this we can conclude that in the beginning of the 16th century there already existed in Kamenetz an elected city council headed by a mayor, and the Woit served as administration head and chief municipal judge; he was also the head of the lavniks [aldermen], beside whom there were also city councilors, headed by a mayor{xxiii}.

[Page 25]

All the settlements along the Leshna River lay within the domain of the Kamenetz starostwo. It should be noted that the heads of the starostwo were among the most important of the nobility of the Polish state, and they apparently leased the city and the surrounding area from the monarchy. The research historians see the Kamenetz szlachta [nobility] as greatly influential, with inroads in the royal court. These were the magnate families Tiszkewicz and Pac (Pacewicz), whom we meet in the 16th century as starostas [administrative officers] of Kamenetz (or Oklepaczy); they also served as voivodes [governors]. Pac was a voivode of Minsk, and the Tiszkewiczes also officiated as finance ministers of Lithuania (Podeskerwy).

King Casimir of Jagiellon, who was especially fond of our town, wrote letters to Pac (Pacewicz) about land disputes over surrounding villages, between them and the Tiszkewiczes. A dispute of this type, which lasted for decades, was over the village of Kiwaticz. During these conflicts, property was set on fire and subjects were murdered. Intervening in the dispute, the crown prince wrote to Pac{xxiv}. Zygmunt I[33] also sent notifications on this subject, threatening the Pacs with legal remedies{xxv}.

Thus we find well–known families of the szlachta [nobility] residing on estates in the vicinity of Kamenetz: Radziwill[34] (Czemery and vicinity) and Sapieha (in the vicinity of Szustokowo–Wysokie[35]). In the 16th and 17th century we find a lower–rank aristocracy near Kamenetz whose descendants became famous in later periods, such as the Kościuszko family. (The residents of Kamenetz recall Stoipiczewo well, as it was located on a hill on the left bank of the Leshna River, in Bliniewicz and in the village of Sechnowic, between Kamenetz and Žabinka[36]).

From documents found primarily in Acts of the Historical Committee of Vilna, particularly in Volume 6, we learn of stiff competition and hostile relationships that existed between the high–ranking nobility and the burghers of Kamenetz–Litowsk. As is well known, the city received a special ordinance granting it Magdeburg rights and voivodeship rights. These rights guaranteed administrative and jurisdictional autonomy to the city. The burghers were exempt from the specific services to the king, including even army service. They had a special privilege, granted by King Zygmunt I in the year 1528, giving the burghers a special right to utilize timber in the surrounding forests for building materials and firewood{xxvi}. The forests of Kamenetz were considered crown property and were referred to as such in the documents mentioned above{xxvii}. This privilege served as a background for disputes that sprung up and lasted for decades. In these documents we read how the burghers were conspiring against the nobles' subjects. There were cases in which they murdered them in the streets of the city{xxviii}. A striking example of this type of case was the long judicial proceedings between Anna Koszczuszko of Stoipiczewo and the burghers who had killed two of her subjects.

In addition, some of the members of the Polish high nobility, such as Sapieha, Radziwill and Pac, were involved in conflicts with the burghers of Kamenetz. These disputes, very typical of that period, provide a small example of the relations that existed between the szlachta and the monarchy. On one side were the burghers of Kamenetz, supported by the king; and on the other side the nobles, who were defending their szlachta rights. A dispute of this type came up in Kamenetz in 1600. The monarchy was represented by Jan Pac, the voivoda [governor] of Minsk; the starosta [administrator][37] of Kamenetz, Castellan Grogery Woina; and the prosecutor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Malchaer Kamenskyi{xxix}{xxx}. In this dispute, Zygmunt III of the House of Waza sided with the mieszczanies [burghers]. Sapieha, the voivoda of Homel, did not appear, instead sending as his representative his confidant Bogdan Cholomowski. In the letter that Sapieha sent, he complains against the government of the crown that it had robbed him of parts of the Kamenetz forests. The dispute was over the woods in the vicinity of the village of Czemery, where Anna Radziwill resided, this area having been given to her as a gift by Sapieha. Sapieha appealed against the very right of the kingdom to litigate against his szlachta in the szlachta's judicial institutions; he refused to sit at the same table with the Kamenetz burghers, since he viewed it as a wrong against the laws of the land{xxxi}. The prosecutor claimed that only the king himself was the giver of laws, and that it had been clarified to the king that the burghers were simply trying to obtain timber for their own use and were not claiming any ownership; if Sapieha had any claims, he should be appealing to the Sejm [parliament].

[Page 26]

A more complex legal dispute took place between Radziwill and the monarchy over the forests, this time in the section between Kamenetz and Czernowczicz. Here, too, the burghers had felled trees, having relied on the privileges granted them by Zygmunt I and Zygmunt III. The forest was located near the villages of Demnic and Liska, where the little river Wisznia flows into the Leshna. Radziwill did not appear at the hearing, either, instead sending a delegate, who relied on documents he had in his possession from the time of Aleksander (1501–1508), according to which the land and the forest belonged to him. The prosecutor for the monarchy brought evidence that the particular section of forest mentioned in Radziwilľs appeal belonged to the crown. The legal decision was interesting: they were ordered to “draw up” the land in dispute, and send it to the king for a decision—that is, they had to draw up a map.

It appears that the city suffered badly as a result of the great wars with the Cossacks, and for that reason it appears that the in 1661 the problem of Kamenetz appeared on the Sejm's agenda. The Sejm decided to provide several reliefs to both the burghers and the Jews. A separate decision by the Sejm also provided a special privilege to the Jews{xxxii}. With extraordinary warmth, the decision takes into account the city's destruction and ruin (desolasjonem), and it releases the Poles and the Jews from taxes for a period of 4 years, except for the levying of the mita (mojt) that was demanded as a customs tax on crossroads, bridges and city entrances. Similarly they were still obligated to provide customs tax on merchandise (an old customs tax on merchandise transiting from one district to another, and a new customs tax—pobur—that was initiated in 1501 on exported merchandise). They were also obligated to pay czopowa—beverage payments that were one of the large sources of income of the Polish government. It should be noted that the lease for most of these taxes and customs taxes were in the hands of the Jews; and the largest tax collectors were mainly Jews who resided in Brisk, who were known as the lessees for the royal taxes and customs tax.

[Page 27]

The status of the town of Kamenetz took a sharp turn in the middle of the 18th century. The city and its vicinity lost their royal status and became the property of a nobleman—the well–known nobleman Wielhorski[38], the most important officer in Lithuania, who was a politician and diplomat. Even before that a change had occurred in Kamenetz's status in the area.

At the end of this period, after the partition of Poland took place[39], the noblemen living in the vicinity were leaving after having sold their estates to local buyers.

In the middle of the 19th century (1878) the city had a population of 6855 residents, among which 5900 (90%) were Jews (including six village communities).

The Beginning of the Jewish Settlement in Kamenetz (To the Mid–18th Century)

It is not easy to write about the history of the Jewish community of our town. The dearth of Jewish documents is onerous. With the exception of a few lines in Dubnow's work, Pinkas Medinat Lita [Records of the Lithuanian Council][40], I was not able to find any document from those ancient times. It is particularly burdensome that we are cut off from the sources of records, containing Jewish documents—these are located in archives that we have no access to, such as those of Brisk, Grodno, and others. Thus there was no other possibility but to recount the history of the Jewish settlement in the town according to the non–Jewish documents, which are mainly in the document centers of the institutions of the government of Poland, located in this country. But these documents and similar ones reveal very little of the Jewish way of life during those ancient times.

Reports on the Jewish settlements in our vicinity appear only at the end of the 14th century. As stated above, the Jews of Brisk were given a privilege by Witold in 1388, but it can be assumed that even before that there existed a Jewish presence in Brisk. We have clear reports on this region only from the end of the 15th century, but here as well one can assume that Jewish communities existed in the area even earlier. (Kobryn appears as an organized community at the beginning of the 16th century). It should be noted that in 1495 the Jews were expelled from Lithuania, at the time of the Lithuanian Duke and Crown–Prince Alexander; but after he was crowned King of Poland he allowed the Jews to return (1503), and their houses and property were given back to them in return for an annual tax (powrotny).

Thus one may assume that the Jewish settlement of Kamenetz began in very early times. Jews are first mentioned in a document from the year 1525 (see below). It is not plausible that during the process of establishing cities in backward Lithuania—at a time when the Jews were given an opportunity not only to deal in trade and monies, but also to purchase estates and to work in every trade—that the Jews were not present in an important town that is located on crossroads and in proximity to a big city as important as Brisk–Litowsk. In a document taken from Lithuanian records, published by the historian G. Bershadsky{xxxiii}, Yevrei [Jews] are mentioned as tavernkeepers, but the document is obscure, and we cannot conclude from it whether the reference was to a Jewish settlement in the town or to isolated tavernkeepers. It should be understood that one can assume that the Jews were in a community, which, if not large, must have at least reached a quorum of ten [the minimum required for communal prayer]. It follows that there was a Jewish community in Kamenetz still earlier. In this very document the following is stated: “On the 26th of February, 1525, the town of Kamenetz receives the rights of voivodeship in addition to the Miburg (Magdeburg) rights of the starostwo [province] Kamenetz. So also the burghers (mieszczanies) receive the rights to the taverns that were previously leased to the Jews.”{xxxiv}{xxxv}

[Page 28]

The development of the towns of Lithuania, as those of other lands, caused the rise of the burgher class, but in Lithuania the rise of this class occurred more slowly than in other parts of Poland. First they received the status of voivodeship, which also provided the town with a town court that was headed by a woit [bailiff or sheriff]. The Miburg (Magdeburg) rights were given to the starostwo of Kamenetz even earlier. As stated above, one would think that the Magdeburg rights, which granted administrative independence to Kamenetz, were given at nearly the same time as similar rights were granted to other cities in Lithuania, such as Brisk, Grodno, Luck, Polock, Minsk and others (1496). But the detail that is most interesting is that the right to tavern leases was now handed over to the burghers. Undoubtedly the dispossession of the Jews from their taverns is closely connected to the granting of specific rights of voivodeship status to the Christian burghers. It is inconceivable that the Jews would have given up their livelihoods of their own free will. It can be assumed that it was a result of the burghers' battle with the Jews of the city.

The Jewish community continued to exist in Kamenetz and its surroundings throughout all of the 16th century. A 1565 document of the lustracja [survey] in the Kamenetz starostwo requires the Jews living in the town of Sarawka, in the province of Kamenetz, to pay a tax, as follows: Eliezer (Lazar)—3 zlotys [gold coins]; Naḥum—3 zlotys; Chiczko—3 zlotys; Pesaḥ—2 zlotys; Stopko—3 zlotys; coming to a total of 14 zlotys. We learn from this that there was a Jewish community not only in Kamenetz, but also in the little towns of the province. In Jewish documents the Jews of Kamenetz are first mentioned at the time of the formation of the Lithuanian Council; that is: with the withdrawal of Lithuania from the Council of the Four Lands[41], a specific sum of tax was imposed on the Jews of Lithuania; they were required to pay it to the Lithuanian treasury minister (podskarbi) in the year 1623 (5383). This matter is what led to the formation of the Lithuanian Council.

In the Lithuanian Council, 3 communities and their surrounding areas were represented: Brisk, the main community; Grodno; and Pinsk[42]. Kamenetz was included in the Brisk communities. But Kamenetz did not merit the same position of respect attained by its neighbors Wysokie and Pruzhany, where the Council actually held meetings several times.

We read in the Council Records of Lithuania, in the regulations of the Council of the year 5430 (1670) that met in Selc, that they were obligated to pay six hundred Polish zlotys to the nobleman Judicki.

[Page 29]

The historical Charter of Main Rights of the Jews of Kamenetz, from the year 1635 (December 11), was given to them by King Wladyslaw IV[43]. It was ratified by his brother John Casimir[44] (1661), and then ratified again by King Michael Wiśzniowiecki[45] in the year 1670[46]. This privilege provides several concessions: (a) a market day in addition to that of Saturday; (b) the right to erect a synagogue, on the condition that it should not be taller or more beautiful than the Christian churches of the area; (c) permission to build a bath house on city land; (d) permission to set up a cemetery in the city or outside it; (e) the right to freely exercise in trade and labor, and also to purchase estates in the town and to construct houses. The mieszczanies [burghers] are warned not to disturb the Jews, neither in their lives nor in their activities to implement the concessions provided to them in the privilege. The privilege threatens that if they conduct any such disturbance, they will be responsible for the consequences and will have to pay fines. Additionally, in the Charter of Rights of Michael Wiśzniowiecki, the size of the fine to be imposed on the mieszczanies in case of damage caused to the Jews is also given in detail. Citing the earlier statement by Wladyslaw IV, a paragraph is inserted that had disappeared from the Charter of Rights of John Casimir: “If the mieszczanies will dare to disturb the Jews, they will be required to pay a fine of 5000 zlotys, which will be divided between the claimants and the government.”

The privilege also refers to the Sovereign Charter of Rights of the Lithuanian Jews. It is conceivable that this is the Sovereign Charter of Rights that was granted to the Jews of Lithuania in 1629, according to which it was permissible to engage in crafts without belonging to the Christian crafts guilds (cech)—and this was in addition to their rights in trade and running taverns.

An interesting fact is that in 1633 Wladyslaw IV, who was known for his favorable relationship with the Jews, decreed restrictions on the Jewish craftsmen that permitted them to tailor garments for Jewish customers only, and that allowed them to freely sell only ready–made garments—and similarly to be occupied only in those crafts that Christian craftsmen were not organized in.

It is therefore noteworthy that the Jewish craftsmen of Kamenetz were among the first in Lithuania to receive privileges to freely engage in crafts at a time when the Jewish craftsmen in the other towns of Lithuania were restricted in their rights{xxxvi}.

The account of the relationship between the Jews and the burghers in Kamenetz reveals an enmity and hatred on the part of the burghers towards the Jews. The Christian burghers of Kamenetz were brazen, and they were engaged in battle with both the nobles and the Jews. Just as in the other cities of Poland and Lithuania, the Jews of Kamenetz won the support of the nobles, as was indicated from the first document from 1525, which transferred the taverns from the Jews of Kamenetz to the burghers. Let us note the harsh language that Wladyslaw IV employed in the privilege from the year 1635: “We hereby inform our starosta [administrator] in Kamenetz and also city offices: we declare it to be our will that all that is written in this privilege should be fulfilled, and we command not to violate{xxxvii} the liberties of the Jews that were provided to them by us.”

[Page 30]

The absence of any monetary value of a fine imposed on the burghers in the event that the Charter was violated by them—missing from the privilege of John Casimir—is also evidence of the harsh battle of the Christian burghers against the Jews; the insertion of this clause into Wiśzniowiecki's Charter of Rights should be understood as evidence that the burghers were not carrying out the privilege. They were undoubtedly fighting with all their might to prevent the privilege from being implemented.

At the end of the 17th century (1693) the Magistrate of Kamenetz presented a protest, signed by 40 town burghers, against the Councilor{xxxviii} Andree Piablewicz, who had given the Jews a lease on the copowa (tax on drink) without the knowledge of the other Councilors or of the entire Magistrate.

It should be noted that during the reign of King John Sobieski (1674–1696)[47] there was a central policy supporting the Jews as in previous times. Thus we see that the finance minister Sapieha handed over the lease on the customs tax of Kamenetz to Isaac Noigmowicz and Yeshayahu Jakubowicz (1693). In that period Kamenetz still served as a provincial capital with a customs house at the crossing between the Brisk region and the region of Podlachia. In the same document Kamenetz appears together with the important cities of Brisk, Pinsk and Jalowo[48], to which little towns are attached{xxxix}. One of the prykomorkis that belonged to Kamenetz was Palisziszcz[49]. The mieszczanies [burghers] were not sitting on their hands, and throughout the entire period of Sobieski's reign they sought out all possible pretexts against the privileges of the Jews of the town. In 1684 the komornik [bailiff] proposes to record in the Vilna Records Book a privilege that John III (Sobieski) granted the city of Kamenetz according to the request of its magistrate. In this document the king verifies charters of rights that were granted to the city by Alexander, Zygmunt I, Zygmunt III and others. The document mentions the Kamenetz burghers' legal suit, adjudicated back in 1631, against the voivoda [governor] Ostap Tiszkewicz (owner of the villages Klepaczi and Paszeki), when he violated the privileges that had long before been granted to the city. John III confirms the rights of the city management and decrees that the Jews living in the city must subject themselves to the city authorities and its jurisdiction. In his decree, Sobieski writes that the Jews must obey the city courts and carry out all the obligations that the city burghers are subject to.

But we should not be misled by any of this. Reading between the lines of the above documents, we learn about good relations between the Jews and their neighbors. The Jews resided in Kamenetz and its surroundings—and one may assume in the villages, as well. In documents from the year 1733 we read about a Jew from the village of Ḥolobork{xl} and similarly of a Jew who lived on a Church estate{xli}. From wills appearing in Kamenetz municipal documents we learn of business negotiations between the Christians and the Jews. For the most part the nobles and estate owners in the region freely engaged in business dealings with the Jews, with no restrictions—something the mieszczanes found intolerable.

[Page 31]

In the beginning of the 18th century, during the rule of the Saxon king Augustus II[50], we begin to see that the conditions are changing: the significance of the town drastically declines, and near it there was now a starostwo in Klepaczi, that belonged to Tiszkewicz, and managed the entire area along the Bialowieze border. Hard times came to the Jews of Poland and Lithuania; blood libels and other fabrications became common occurrences. The political reactionaries, mainly the Kler [clergy], spread superstitions among the people, regaling them with terrifying tales of Jewish witches who had made a pact with demons—and thus persecution of the Jews became commonplace. In particular they frightened the people that the Jews had cast an evil eye on the crops. An echo of this period comes to us from Kamenetz, as well. A document dated 17 June 1718 recounts: “In Kamenetz–Litowsk, two Jewish women accused of witchcraft were imprisoned. Chaika Shmulicha hid a pot containing odd substances in the trash. These included: flour, poppy seed, eggs, barley, and other things. Chaika Shmulicha claimed that she did this at the request of another Jewish woman, Yospe. Yospe claimed that she had hidden it in order to cure her daughter of an illness. This Yospe, the wife of a musician{xlii}, wept and said that she had been at a znacherke [sorceress], who had instructed her to prepare it at night and place it in a hidden place for safekeeping from the evil eye, to protect it from the view of wicked people. The two of them were taken to the fortress under guard.” We do not know what became of these two Jewish women, but this libel also follows the pattern of fabrications against the Jews of Brisk and its surroundings when the Jews of Brisk were swamped by blood libels and accused of aid to the Swedes (1703).

The war of the Kamenetz residents against the Jews finally bore fruit: the burghers protested before King Augustus II—opposing the privilege from the year 1679—that “the Jews of Kamenetz are living lives of comfort and convenience{xliii} in the city: they are serving brandy, mead, beer and other strong drinks; they are doing business freely and opening shops in the marketplace within the city itself; they are trading in houses, estates and church property; they are selling textiles and dry goods, both retail and wholesale{xlv} by the length{xliv}; and they are selling ornamental goods of various kinds. They are also distributing their merchandise in the Old City and lowering the rents—and all of this is causing pain and suffering to the Kamenetz burghers.”

In his response to these charges, King Augustus II the Saxon ordered that the Jews should be forbidden from building courtyard apartments and from dealing in liquor. Additionally, he ordered the starostas [administrators] to limit the Jews' business in shops. This protest of the burghers relied on the privilege that had been granted to the city by Michael Wiśzniowiecki, the same king who had ratified the privileges to the Jews of Kamenetz and had even extended them. We saw above that in 1684 the mieszczanes [burghers] presented a complaint on the granting of over–extensive rights to the Jews, and they also referred to the privilege that had been granted to the burghers. Although this seems somewhat puzzling, it should not surprise us once we consider how privileges were being granted to the Lithuanian Jews by the Polish kings. The Jews used to obtain these privileges at the cost of much toil and great sums of money. It was for this reason that they were described as “geese that lay golden eggs” in that period, as well—for every approval of a privilege or a new grant involved handing over “golden eggs” to the king, to the members of his chancellery, to the voivodeship officials, and to others.

[Page 32]

And thus the situation we are familiar with was created, that general and particular privileges were granted in contradiction to other privileges that kings were granting to burghers. The main goal of the latter privileges, obtained by the burghers, was to limit, as much as possible, the Jewish economic activity with its competitive nature. Sometimes the two sides reached a compromise agreement; but the burghers could not maintain whatever restrictions had been agreed to, because the realities of life were too powerful for them. And so they would try to get the authorities to intervene; but the Jews would, in return for money, receive new concessions.

From the details of the above protest we learn that Kamenetz was then divided into two parts: the Old City and the New City. It is easily understood that the western part of the city was the Old City; it included Litowski Street and its vicinity. The Jewish part of the city included the center and all the side–streets near the large Beit Midrash [House of Study], which faces the Leshna River—including the Talmud Torah, the bathhouse, etc.

We also learn that the magistrate of Kamenetz was a very powerful and influential institution. Its arrogance was unparalleled. It did not even take orders from the voivoda [governor], often turning instead directly to the king. This is the source of the difficult struggle for existence that was the lot of the Kamenetz Jews. We can easily envision how the mieszczanes battled against the Jews—and particularly against the Jewish peddlers, who would be going around through the villages and estates, illicitly selling merchandise. And the taverns that served as the source of the Jews' livelihood were like thorns in the burghers' flesh. From the above documents we hear an echo of the accusations by the Polish anti–Semites, of the sort made by well–known anti–Semites such as Stanislaw Macinski and others.

The Jewish population of Kamenetz numbered several hundred. This can be deduced from a document dated 1705: “The szkolnik (gabbai [synagogue functionary]) Szymon from the community of Brisk presented the budget of the head tax of the communities and of the towns of the Brisk region. In the meeting a sum of 1384 zlotys was levied on Brisk; on Kobryn—315 zlotys; on Pruzhany—485 zlotys; on Kamenetz—250; on Melcz—100; etc.” In the beginning of the 18th century, during the period of Jewish central autonomy, the Jews payed Lithuania a total head–tax of 60,000 zlotys. But with the annulment of autonomy in the year 1764, the communities were required to pay 2 zlotys per head for each person older than one year. It can thus be assumed that in that [earlier] period the calculation was based on one zloty per head of age one and over. Since the Jews of Lithuania were then paying a total head–tax of 60,000 zlotys, it is reasonable to estimate the number of Jews in Kamenetz at the beginning of the 18th century as 200 souls over one year old. This was, then, a small community, but by the scale of that period a community of this size was considered important.

The history of the Jews of Kamenetz has not yet been written. As stated above, documents on its internal life—the daily life, the culture, the economic struggle, the rabbis and the religious scholars—are unavailable to the present author. But even the little information that has been presented here has borne witness to a Jewish community fighting for its historical existence.

[Page 33]

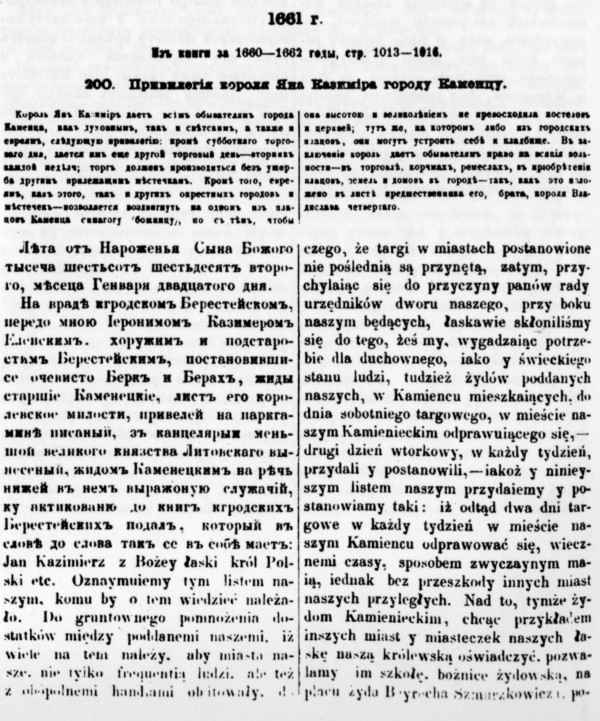

Translation of the Royal Privilege—from the year 1661—Granted to the Jews of Kamenetz by Jan Kazimierz, King of Poland[51]

In the year one thousand, six hundred and sixty–one A.D., on the 20th of January—in the court office of the city of Brisk, before Hieron Kazimir Alenski, standard–bearer and under–starosta—the Jews Berek and Boruch, heads of the Jews of Kamenetz, personally presented a letter from his gracious royal highness, which is a privilege written on parchment, written in the Lesser Council of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was given to the Jews in Kamenetz and copies made in the records of the city of Brisk. It states the following:

Jan Kazimierz [John Casimir], King of Poland, by the grace of God etc. With this letter we proclaim: In order to increase and enhance the prosperity and welfare of our subjects, we are interested that our cities shall have control not only over population but also over all branches of trade; and for that purpose, marketplaces have been set aside in the cities. Hearkening to the words of our officials of the royal court, who are with us, and who have advised us—and in keeping with the needs of the people of the religious and secular classes, also in keeping with the needs of our Jewish subjects who dwell in Kamenetz—we declare that in addition to the market day taking place in our city Kamenetz every Saturday, there shall be an additional market day every Tuesday, so that henceforth there shall be two market days in our city Kamenetz, and so shall it be in perpetuity, without causing any losses to nearby cities.

To demonstrate our royal grace to those Jews of Kamenetz, following the example of other cities and towns in our kingdom, we permit them to establish a study hall and a Jewish synagogue on the lot belonging to the Jew Beyrech Smuszkowicz, located near the lot of the burgher Chrostowski, or in some other location on someone else's property, with the condition that it may not be greater in either height or beauty than the churches and Russian churches of the city.

We also permit them to establish a bathhouse on a city lot that has already been purchased from a man of great fame, Jakob Kusznier. And they may also establish a cemetery on a lot, either in the city or outside it. And finally we grant them every liberty to open shops and taverns, and to occupy themselves in all crafts, to purchase estates and city lots. And in order that they do not suffer therewith any hardships or losses{xlvi} at the hands of our burghers, we impose a fine following the letter of our brother Wladyslaw IV—whose memory we hold sacred—from the 11th of December, one thousand six hundred thirty–five according to our calendar. And we hereby proclaim and additionally emphasize with all our strength and inform thereof to our citizen the starosta [administrator] in Kamenetz from now and henceforth, and we also inform the authorities of the city, and command to safeguard the liberties we have granted to the above Jews in the Charter of Rights to the Jews of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania without any interference whatsoever.

Given in Warsaw, in the Sejm elected by the crown, on this day, the 16th of June, year one thousand six hundred sixty–one, in the 13th year of the reign of our Polish and Swedish lord, King Jan Kazimierz; and the king has signed it in his own hand: Jan Kazimierz.

The Secretary of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania brought this letter to be recorded in the books of the city of Brisk.

[Page 34]

Footnotes by original author (Sarid):

|

[Page 36]

|

[Page 37]

|

[Page 38]

|

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kamenets, Belarus

Kamenets, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 Dec 2020 by LA