Rzeszów was a private city until the end of the 18th century. Its development was dependent on the activities of the owners of the city. Rzeszów was tiny during the period of the rule of the Ruthenian noblemen. The first owner of the city, as well as the neighboring towns was Jan Pakoslaw from Strozysk in the Wislica region in the Wojewodztwo of Sandomierz. He was the son of the Knight Pakoslaw who owned Strozysk and two other regions. His father gave over to him the region of Rzeszów in 1345 due to his excellence in his diplomatic missions to the Tatars. He worked in the diplomatic corps and was on several occasions sent as an emissary of King Kazimierz the First during the years 1363-1366 to Pope Urban the Fifth in Avignon, with regard to the issue of the divorce of the King from his wife Adelaida and the establishment of the University of Krakow.

In the privilege of January 19, 1354, King Kazimierz the Great granted the city of Rzeszów and the surrounding area to Jan Pakoslaw in return for his successful activities as the emissary to the Tatars. The king established the Magdeburg charter as the legal system for the city, and granted to Jan Pakoslaw the rights to collect taxes, punish murderers, build palaces, and establish villages.

It is probable that the city had already been established before 1354, and was in a state of destruction at the time of the granting of the above mentioned privileges. Since the king freed the city from the jurisdiction of the Starosta and Kasztelan [2] courts, the city was set up according to the Polish or Ruthenian law.

However, the city was able to remain in peace only for a brief period. In 1458, the Turks invaded, and the Wallachians destroyed it by fire and sword. After the death of Jan Pakoslaw, the founder of the city, it was transferred to his children: Jan, Felix, Stanislaw and his two daughters Malgorzata and Ofka.

The city of Rzeszów was given as a dowry to Ofka, who married Zbigniew da-Sampsko. Their son Jan Zbigniew da-Rzeszów (Rzezowski) died in 1462. After his death, Rzeszów and its environs transferred to the possession of his sons and daughters.

The final Andrzej of the Rzeszówski family is known from his adventures and judgements. He sold his land. The city of Rzeszów then passed to the ownership of Mikolaj, the grandson of Malguzata, who died in 1574 without leaving any children. His sister Katarzyna was married to Niewiarski, and his sister Zofia to Mikolaj Spytek Ligenza. In the event that their brother would leave no children, the sisters were supposed to receive the city and environs as an inheritance. That is indeed what happened. Rzeszów was included in the portion that Zofia received. Mikolaj left two daughters: Podmiana who was married to the knight Wladislaw Ostrowski, and Konstancja who was married to Jerzy Lubomirski. According to his will, Ostrowski was supposed to receive Rzeszów along with 39 villages. After Mikolaj Ligenza died, conflict broke out between his heirs and his widow, and only in 1638 was a compromise reached due to the intercession of a special committee. Nevertheless Lubomirski continued attacking the city until he succeeded in taking possession of Rzeszów. The Lubomirski family ruled over Rzeszów for 150 years – these are the descendents of Jerzy Hieronim, the first born son of Jerzy Ignace (1685-1753); Teodor Hieronim (1753-1761), who died at a young age; and after him his widow ruled in place of his children. Her eldest son was still ruling at the time of the Austrian invasion.

At this point, there is a lengthy footnote in the text in reference to Mikolaj Spytek Ligenza, which is as follows:

Mikolaj Spytek Ligenza was the most prominent figure among the owners of Rzeszów. He is a descendent of the Snatori family of the Wojewodztwo of Lancut. He owned several properties in the Wojewodztwo of Krakow in the 14th century.

Mikolaj was born in 1562. In 1590 he became the Starosta (leader) of Zidaczow. During the period of 1613-1619 he became the Kasztelan of Zarnow and Sandomierz. He married Zofia Rzezowski in 1580, the daughter of Jan Rzeszówski. He died at age 75. During his lifetime he was known as being a generous hearted nobleman, who cared about the wellbeing of the residents of his properties. Complaints were never heard about his leadership. He established many public institutions such as hospitals and churches.

He had particular concern for Rzeszów, and he donated a significant some of money to establish it as a center of trade. As a faithful Catholic, he donated much money for the needs of the churches and monasteries. He paid particular attention to the protection of the city of Rzeszów. On August 8 1627, a draft notice appeared for the residents of the city, both Christian and Jew. They were required to arm themselves with guns, along with a certain amount of bullets and gunpowder. Only the women and children of age 12 and under were freed from this draft. He ordered that a list of all of the properties, gardens and houses be prepared. Hetmans [3] were in charge of this defense: the Hetman of the city, the Hetman of the suburbs, and the Hetman of the Jews. In 1627 Piotr Fanialk filled the Hetman of the suburbs the position of the city Hetman was filled by Lucas Gajdziak and Moshe Aptarz filled the Hetman of the Jews.

Ligenza played an active role in the activities of the state. He was a representative to various Sejms (government bodies), and he was an advisor to King Zygmunt the Third during the time of the revolt of the noblemen under the leadership of Zbrazidowski (1601).

He filled several roles as senator and commissar for the king. Several of his speeches to the Sejm were published. In his speech regarding the protection of the kingdom in 1633, he advised the placing of the burden of taxes upon the "plebeians (the simple folk) and the Jews".

According to this privilege, Polish law was applied to the city, as opposed to the Magdeburg law. The city was given the right to establish for retailers, a cellar under the city hall for the sale of wine, mead and beer, workshops for weavers, stalls for the sale of salt. The nearby villages were forbidden to do business with merchandise that did not pass through the city. As well, weights and measures were accurately defined.

According to the privilege of 1354, the owner of the city and his heirs collected a tax on merchandise that passed through the city. The owner of the city split the tax revenues with the importer. In 1475, the income from this tax amounted to 38 grzywny. The fee for a wagon laden with merchandise was 1 groszy; for the sale of a horse – ½ groszy; for the sale of an ox – 4 dinars; a rider paid 4 groszy and a pedestrian paid 2 groszy.

After the fire, the king granted the city the right to collect a bridge toll for horses and oxen that passed through Rzeszów.

These tolls were used to repair the bridges and for other civic expenditures. As this revenue was not sufficient to cover the needs of the city, the representatives and senators of the Rusin area requested in 1569 the permission for the city owner to raise the bridge toll, in return for his commitment to keep the roads and highways passing through Rzeszów in good repair. Mikolaj Rzeszówski defined the affairs of the city in a special privilege on July 25, 1571. After the authorization of this privilege, the amount was set for the city at 46 guilder as the annual amount from the tax revenues which would be used for this purpose, and the specific roads and highways that were in need of upkeep were defined. This amount would be paid each year from 1559, as long as the owner of the city would retain the right to collect the bridge and highway tolls. The residents of the city would be allowed to use the right bank of the Wislok for pasture. According to this privilege, beer from Przemysl was not allowed to be sold in the taverns. Any permit to provide liquor was to be requested from the town council. In this privilege, the market days were set for the sale of grain, wheat and spirits in the city center. This privilege, which was based on the principles of Germanic law in Poland, also included paragraphs on various matters of civil administration. Civic matters were to be decided by a council headed by a mayor (proconsul or burmistrz). The authority of the council was limited, and dependent on the edicts of the owner of the city, despite the fact that during this period the relationship between the city and the city owner was shaky.

The mayor was appointed for a set term. The rights of the city were expanded. In 1599, after the death of Adam Rzeszówski, when Mikolaj Spytek Ligenza was the owner of the city, the city was granted a new privilege after the fire that destroyed the city. This was one of the most extensive privileges ever granted to a private city.

In the preface to this privilege the owner of the city acknowledged that all disasters occurs as a punishment from Heaven. He acknowledged that it is his desire to behave toward his wards with love, and therefore he grants law and order as well as freedom to the city.

After the approval of this privilege, the city was granted the revenues from the slaughterhouses and from the tax collection in perpetuity. Up until this time, these revenues were given to the head of the city for the purpose of improving the roadways and highways.

The city was freed from the requirement of purchasing all of its provisions – grain, wheat, mead, oxen, and salted fish, and was granted freedom in this area. It was permitted to import mead into the city without having to pay tax upon the profits of the business transaction.

The city received the right to exempt those who built wooden houses from payment of rent for houses, gardens, business endeavors, and other such levies for ten years. Those who build mansions were exempted for fifteen years. The protection fee (szarwark) for homeowners was reduced by 50 groszy, and for tenants by 12 groszy. All residents were permitted to import spirits for two years without payment of any tax to the owner of the city. The residents were promised the freedom to build and to dwell in the city, to sell, and to leave the city without any levy or difficulty. In the privilege, the owner of the city promised to produce new surveys of the gardens and properties, and to enlarge them for the poor citizens from available non-built up land in the area. He also took it upon himself to intercede before the king and the Sejm for the reduction of taxes.

Most of his activities were directed toward the security and protection of Rzeszów in the event of war or an enemy invasion. On account of the numerous attacks and wars, Ligenza developed a comprehensive plan for the protection of the city. He commanded that a moat be dug around the Bernardine monastery and be filled with water, which would flow toward the palace. When the water level rose, a bridge had to be built from the gate of the palace to the Pierrian monastery. He ordered that the Christians and the Jews cover the cost of these improvements and renovations by mutual payments. After the Tatar invasion of 1624, ramparts were erected from the Wislok River, surrounding the Jewish synagogue, and going all the way to the church. A special tax was imposed to cover this expenditure. The citizens used this opportunity to gain further concessions, since they were required to cover more than half of the expenditure. Ligenza conceded and covered 2/3 of the required expenditure for the digging of the ramparts. He was not satisfied with this, and he wished to conscript the residents, both Christian and Jewish, into active security duty. In 1625, every household was required to own arms, gunpowder and bullets. On every second Sunday, the citizens were required to participate in exercises, including target practice with guns. A prize of six groszy would be awarded to anyone who hit the target with a gun, ½ guilder to anyone who did so with a mortar, and 1 guilder to anyone who did so with artillery.

The fortifications that were required to be built by the citizens included fourteen of the areas of Ligenza's plans, that is from the synagogue to the church. Each section was to be built by a group of seven to nineteen men. The Jews were given their own fortifications to construct.

The privileges were conducive to the development of commerce in the city. This was particularly true of the privilege granted by Stefan Baturi in 1578, according to which the citizens of Rzeszów were entitled to insist that no travelling merchant with merchandise be allowed to bypass the city, and if he was caught doing so, he would be arrested and his merchandise would be confiscated. The city treasury and the owner of the city would split the revenues of the sale of the confiscated goods.

In 1589, the city had nearly 2,240 residents, mostly Poles. Only a small number of the residents were Ruthenians and Germans, as can be established by searching for Germanic names among the residents. Jews were found in the city in recognizable numbers during the period of Ligenza, and we will speak more of them in the chapter about the beginning of the Jewish settlement. During the period that Ligenza was the owner of the city, the economic base of the city consisted of artisans, farmers, and merchants. The character of the city was set by the artisans and merchants. The artisan guilds did not receive benefit from the royal privileges that were granted to the city, but rather fthe rights granted to them by the owners of the city. Only very few artisans received personal privileges from the king. The guild of spinners was the oldest guild in the city, having received its charter in 1439.

The spinners of Rzeszów were expert at their field, and they were not dependent on any judicial privileges. The heads of their guild adjudicated their disputes and judgements. The most active guilds were those of the tailors and weavers, who often engaged in difficult disputes in the interests of their members.

The furrier guild was another important guild. It was organized at the beginning of the 16th century, and received its privilege from Adam Rzezowski. Mikolaj Ligenza, who required them to participate in the protection of the city and to bear arms, expanded the privilege. The guild of shoemakers received its privilege during the time of Mikolaj Rzezowski in 1569. The physicians, medics and pharmacists organized into their own guild, based on a privilege of 1699.

The smiths became very prominent in the economic life of the city from the 16th century. The watchmakers joined with the smiths into a single guild. The smiths of Rzeszów were known throughout Poland for their fine workmanship. A valuable gold object was commissioned from the head of the smiths, Wawrzyniec, via Ligenza on the occasion of the marriage of King Zygmunt the Third. The locksmiths, blacksmiths and armament makers organized in 1627. Aside from these artisans, the bath attendants who worked in the public bathhouses, the glaziers, rope makers, belt makers, cord makers, bakers, millers, beer and mead brewers, soap makers, and candle makers also organized into guilds. The guilds and organizations were set up by charter, and their members consisted of professionals, apprentices, and trainees. A professional who was a citizen of the city was the only member with full rights. The guilds and organizations paid a special tax to the owner of the city for the right to engage in their trade, as well as rent for the tools and anvils that belonged to the owner of the city.

According to the decree of Mikolaj Ligenza, all of the guilds were obligated to participate in the defense of the city, and to bear arms. As can be readily understood, within the guilds, and between the guilds, there were disputes with their internal leadership, as well as with the leadership of the civic institutions.

The geographic location of Rzeszów, which was on the main communication line of Lesser Poland, and the conditions that were created by the privileges that provided economic opportunities, as well as the autonomy in the civic government – all these factors created natural foundations for the development of trade. However, the invasions, wars and disputes with the owners of the city significantly impeded the economic progress to a serious degree. This was with the exception of the local commerce in stores around the town hall in the center of the city, as well as the wholesale trade with Hungary, which was primarily with cattle and manufactured goods. Thanks to the privilege of 1576 that freed the city from taxes and gave it the right to run fairs, Rzeszów became a main depot for merchandise from Rusin, Podolia, and Wallachia. The annual fair on April 23rd attracted merchants and visitors from outside the city and even from outside the country. This caused competition with the city of Lancut, which attempted to attract merchants to its fair that was held on the 25th of April.

In 1590, this situation resulted in open warfare, when Stanislaw Stadnicki (Diabel) of Lancut along with his men attacked Rzeszów, blocked off the access roads, and confiscated merchandise from the merchants who were travelling to Rzeszów.

Ligenza did not accept this quietly, and he arranged an attack on Stadnicki. This conflict, which took place in the courts as well as by attacks on the fairs, lasted until 1619. The intervention of King Zygmunt the Third did not help the situation. Finally, Ligenza was victorious, and the fairs took place in Rzeszów.

The cattle trade with Hungary via the Wislok River flourished in the 16th and 17th centuries. Due to the efforts of Ligenza, the river was declared as a navigable river, fit for shipping. Grain, flour, wood, fruit, sheep, fish, cheese and butter were exported from Rzeszów to the interior of the country.

The export of wheat from Rzeszów to Danzig began in the 1620s. The first merchant to be occupied in this export was Jerzy Blutnicki. Ligenza granted him land in thanks for his efforts.

Business in Rzeszów further expanded in 1633, when Rzeszów received a privilege allowing it to establish warehouses for fish and Hungarian wines. In the first half of the 17th century, Rzeszów was one of the most significant economic centers of Poland. It comes as no surprise that in 1638, an inspector from the church diocese made note of the economic success of the city, where annual fairs were held which served as public gatherings of merchants from the entire country.

The various privileges contributed to the economic foundations during the 16th and 17th centuries. These privileges served as the legal basis for administrative and economic life of the city and its residents. Aside from written authorizations from the owners of the city, Rzeszów also received privileges from the kings. The first was from King Alexander in 1520, which cancelled the fair that was held during the holy day of Wielkanok [4] in Lancut, since it caused damage to the fair in Rzeszów. In response to the request of Rzeszówski, King Stefan Baturi in 1578 granted a permit for all of the fairs in Rzeszów. In this privilege, the legal status of the city with respect to the merchants was defined.

In 1633, through the efforts of the Sandomierz Wojewodztwo, the merchants of Rzeszów received a permit from King Wladislaw the Fourth to establish warehouses for wine and fish. In 1651, the city was granted the right to hold an additional fair. In 1667, Jan Wowieski the Third granted the city the permission to hold a four-week long fair. The number of fairs increased further due to the privilege of King August the Second in 1727.

As can be understood, these fairs played an important part in the improvement of the economic situation of the city. However, the fires that brook out in 1427, 1524, 1580, 1621, 1657, 1698, 1709, and 1728 and the wars that took place during these nearly three hundred years repeatedly hindered the progress and development. The city suffered greatly in 1603 from two attacks caused by family disputes. Andrjez Ligenza, the grandson of Mikolaj, destroyed the city, plundered and pillaged the inhabitants, broke into the palace and removed 20,000 taller of public funds, as well as clothing, rugs, and weapons. He also plundered the church and killed several dozen people.

In 1657, Rakozi attacked the city and the result was fires, pillage, and destruction. Many residents were forced to flee from the city. Between 1702 and 1710, the city suffered from invasions by the Swedes and Saxons.

All of the legal, administrative and judicial authority of private cities rested with the owner of the city according to Polish law. This situation limited the autonomy of the city. During the course of the 16th century, Rzeszów enjoyed a very wide and well-grounded autonomy, as is proven from official documents that were publicized after the publication of the book by Jan Paczkowski. The limiting of the autonomy of Rzeszów did not come suddenly. It was the result of development during the course of several decades. The owner of the city and his administrators held most of the civic administrative positions themselves. The fact that the owner of the city was responsible for all judgements and complaints limited the importance and esteem of the city and its courthouse to a significant degree.

All complaints against the judgements of the civic courthouse and decisions of the council were brought to the palace, where the owner of the city andhis second in command held court. The owner of the city had the final say in all legal and administrative matters. That is, he held all the rights of confiscation and forfeiture of property. Since the owner of the city did not live in the city, he appointed a commissar who conducted civic matters. He also appointed an official to oversee the lands surrounding Rzeszów. The commissar was responsible for arranging elections to the city council. The citizens suffered on numerous occasions due to the improper, and even cruel behavior of those in charge of the palace. This occurred particularly during the 18th century when Lubomirski limited the rights of the citizens.

In the 18th century, the residents of Rzeszów required direct administration from the palace, since the city council at that time did not act in a consistent manner, and many complaints from the citizens were taken directly to the palace.

The courtyard of the owner of the city fulfilled a central role in the national administration. As a private city, the lot of Rzeszów was tied to the lot of the families of the owners of the city – at first of the Rzeszówski, and later of the Ligenza and Lubomirski families.

The administration consisted of a) a council and a magistrate with five advisors, under authorization of the owner of the city. The position of magistrate was filled in a monthly rotation by one of the 5 advisors. A notary, generally with the title of doctor or graduate of legal science directed the civic offices. b) a courthouse, consisting of seven to nine sworn members, headed by an advocate (wojt) who was appointed by the owner of the city.

Between the years of 1673-1724, the city was run by eight officials, and later by ten leaders of professions. From 1709, there were one or two treasurers and two public defenders. From 1715, the city officials also included two church superintendents and two hospital superintendents. From 1724, there was also a supervisor of fences, and a builder of roads. From 1750, the civic prosecutor, the palace prosecutor as well as the collector of the fair dues were included in the civic leadership.

With the passage of time, the number of members of the civic leadership increased to 26 and even to 30 people. Each role was filled by elections that took place annually with the permission of the owner of the city or the governor. Until the end of the 16th century, the heads of the public tribunal was also included in the civic leadership. According to the decision in 1591, twelve people were chosen for that role. During the 17th and 18th centuries special gatherings of the people took place in order to decide on matters of non-regular taxes, accepting suggestions from the palace, as well as other important matters.

The civic revenue was obtained from its properties, from the dues paid during fairs, from taxes and fines. There were fields, houses, and various manufacturing endeavors such as liquor and spirits stills, brick kilns, and mills were owned by the city itself. Civic income came from the fees of weights and measures, taxes on wines, merchandise, wagons (according to the number of horses), and the rental fees for stores. The tax on food production was an important part of the revenues. The expenditures were divided between regular expenses and unusual expenses.

In order to get an idea of the amount of revenues and expenditures, we will point out here that in 1787 the total revenue was 955 guilder and the total expenditure was 502 guilder. In 1794 the total revenue was 4,221 guilder and the total expenditure was 2,459 guilder.

Over and above the civic taxes, the residents paid royal taxes (szos), property and building taxes (czopowe), and liquor taxes.

There were also payments that were due to the owner of the city. Every citizen paid a tax for the land in the outlying areas, for fields and houses. Artisans and merchants paid a business tax. Aside from this, each individual was required to supply provisions to the palace according to his profession. Bakers were required to supply bread for the palace, butchers – meat, and artisans were required to supply their workmanship to the palace according to its needs. The Christians were also required to pay a church tax.

|

|

| Rzeszów in 1856, Drawing by Stenczynski |

Footnote 9: The second prince of the Lubomirski family was Jerzy Ignace (1687-1753), who ruled the city for more than fifty years. In 1707, he received Rzeszów as an inheritance from his father Hieronim, the Polish Hetman and Kasztelan of Krakow, who was one of the supporters of the Sas Kings August the Second and Third. He settled in Rzeszów after his marriage and concerned himself with family matters. He was a staunch Catholic, and donated much money to the churches of Rzeszów, he founded a new hospital, as well as a hospice for the poor of the city and the surrounding areas.

Lubomirski did not hesitate to arrest and imprison for six weeks the mayor of the city, Tonelar, who had spoken out against the owner of the city with harsh words. The palace worried first and foremost about its own interests, even if they were in opposition to the welfare of the city. Any sale or purchase of a house or a property in the city, and even a swap, required a permit from the owner of the city. This limited the individual power of the citizens. Lubomirski granted many favors to the noblemen, in particular to the palace officials. These grants included fields and houses in which they could reside without being subject to civic judicial authority, and even without being subject to the judicial authority of the owner of the city. These noblemen lived wanton lives. They attacked the citizens on numerous occasions, and it was impossible to bring them to justice. This matter angered the residents and caused unrest and dispute. However, the palace paid no attention to the complaints of the city.

The decree of 1750 shows the extent to which the palace controlled the lives of the citizens. According to this decree, it was forbidden for the merchants to place imported fabric in the display windows before the wives of the palace officials had a chance to look over the fabric and purchase what they wanted.

The citizens suffered from extortion of money and goods, various troubles and even torture at the hands of the Gubernator Tycinski over the course of many years, until the complaints reached to the owner of the city. He was brought to justice after it was proven that he stole 5,150 guilder from the palace treasury as well as extorted 4,179 guilder from the citizens. The owner of the city ordered that an announcement be made in all the churches, public places, as well as the synagogue, that anybody that had a complaint or financial claim against him should bring it to the court.

The Gubernator Tymotycz Olmiczer was no better than he was. He ruled from 1744-1747, and ended up with a conviction as well.

By the beginning of the 18th century there was already a noticeable reduction in business. There were many reasons for this.

In 1729, Lubomirski imposed several troublesome conditions upon local business, the weekly market day and the fairs, which affected the merchants from outside the city. Any merchandise that was brought into the city was subjected to a stringent inspection, and payments were demanded for benefit of the palace. Any merchandise that was not registered would be confiscated. Merchants who conducted business from their homes were required to produce detailed reports of their turnaround every Friday. Special controls were imposed on the sale of tobacco – a special permit was needed for this purpose which would only be issued to citizens of the city. Non-citizens were forbidden to sell tobacco during the fairs, according to a decision of the court in 1678. Furthermore, a special tax was imposed on tobacco.

The general depression and wars in the 1730s caused many merchants to leave the city, since they had no opportunity to earn a livelihood. Some of them left the new city and moved to the old city.

Jerzy Lubomirski attempted to stem this emigration. He imposed fines and sanctions upon those who left their homes in the new city to live in the old city. However, these efforts were to no avail, and in 1749 the palace issued a decree that all locals as well as foreigners who lived in the new city would be freed from all civic taxes and payments to the palace for seven years. This excluded royal taxes. They would be permitted to engage in business, and would be permitted to serve liquor without any need for payment for seven years. Those who would renovate abandoned houses would be freed from all payments and taxes for four years, and the ownership of the houses along with their lots would be transferred to the new dwellers. These promises did not help, and the trend of emigration continued until 1750. However, we cannot ignore the fact that a similar situation existed in other cities, such as: Czanow, Poznan, Bendin, Biecz, Lancut, Torun as well as others. This was a consequence of the general attitude of the nobility toward the cities.

In the first half of the 18th century, the city was invaded numerous times, once by the Swedes, once by the supporters of Stanislaw Laszczinski, and once by the Confederates. Each invasion brought with it suffering, pillage and robbery.

Epidemics and starvation came along with the invasions (in the fall of 1713, 1715 and 1720). Obviously, with such conditions, the cultural and social condition in the city was poor.

With the exception of the school of the Pierrian monastery, which had among its teachers Stanislaw Konarski and the well-known pedantic Onufry Kopczynski, there was no other school in the city. Illiteracy was prevalent, even among the noblemen and the upper class of the city. For the most part, the signatures of the civic leaders appear on documents as the sign of a cross.

There were very few books in the homes of the citizens, with the exception of prayer books. The home of the merchant Robert Metlant was the only home with a personal library, which included Latin and Polish books. After his death, nobody could be found in Rzeszów who would buy his library, which was later sold to someone in Jaroslaw.

The palace caused difficulties also in the field of education. In 1743, a decree was issued to the schools outside of Rzeszów as well as to the Pierrian school: "Not to accept anyone from amongst my subjects without a written permit from me". A small number of citizens studied in schools, and only in very exceptional cases was someone able to study in the University of Krakow.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, there were three pharmacies in the city. The pharmacist Macei Alexandrowicz was a learned man, and in his library there were scientific books in Latin and French about the subjects of pharmacology and medicine.

There was tension in the city during the time of the war between August the Second and Karel the Twelfth. The city suffered from military invasions by the disputants, who pillaged the residents and caused significant damage to the city. Lubomirski was not successful in setting up fortifications in the new city, in order to defend it properly. The city was able to recover only after the war.

Midway through the 18th century, the center of economic life moved to the new city. At that time, commercial relations started with outside the country. Foreign merchants would come to the fairs. A new bridge was built in order to facilitate the connection between the two parts of the city.

Various national and military events passed through the city during that period, which brought suffering to the residents of the city. In 1768-1769, the Confederates from Bar captured the city. They defended themselves and fortified themselves in the palace. There they found mortars, guns, revolvers, bullets, gunpowder, and various other weapons. The Confederates weakened and the Russian army captured the city.

Instances of theft, robbery and pillage became commonplace in the city. The palace was forced to take measures against this. However none of these measures were to any avail – neither judgements issued by the court, nor punishments, nor even death threats. Night watches, the closing of open fields and the erection of fences around buildings and the entire city also did not help. These types of events were prevalent at that time in all the rest of the cities of Poland.

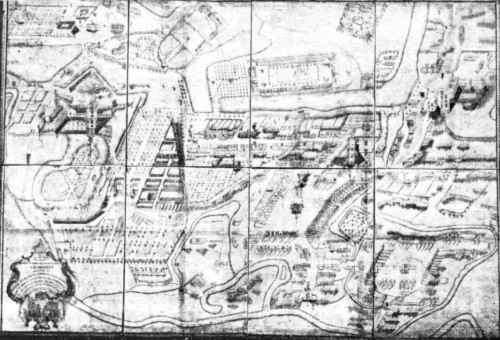

|

|

| Rzeszów in 1762, a drawing by Captain Weideman |

In 1782, when the decree was issued about the organization of the "Dominat" (city council) which was granted very far-reaching powers, difficulties arose with regard to relationships with the landowners. In the region of Rzeszów there were not enough Poles available to serve as land superintendents. However since Rzeszów was a private city, the dominus (owner of the city) had great power in the realm of the judiciary and police, and therefore the regional administrator attempted to limit his authority. Similar attempts were made by the regional administrators with respect to the cities of Brody, Jaroslaw, Zamocz, and Tarnow, which were also private cities.

The regional administrator Baron Ridheim conducted a harsh investigation into the economic powers of the owner of the city. He also imposed harsher conditions on the Polish noblemen. He said "let them be beaten to the dust, and thus they will be more complacent and will subject themselves to the authority of the government".

In one financial review, Baron Ridheim determined that the income of the city was only 370 guilder. We can get an insight as to how high was the degree of tension between the citizens and the palace from the fact that at the beginning of the Austrian administration, a group of citizens came forward with a request to the regional administrator that the city be freed from the authority of the palace, and a new council should be established. The reason given for this request was that the palace places heavy impositions on the citizens, and acts as an enemy of the city.

During the era of Austrian rule the city developed as an economic center, particularly in the latter half of the 19th century after the important railway from Vienna to Lvov began to pass Rzeszów. The city also developed greatly from a cultural perspective. In 1869, there were already many educational institutions over and above the elementary schools. There were 540 students and 25 teachers in these institutions. There was a teacher's seminary with 103 students and 17 teachers, a general school for youths with eight classes and seven teachers, and classes for girls with 17 teachers.

From an economic perspective, there was great progress in mid-range manufacturing, as well as in wholesale and retail business. In order to furnish the sums necessary for the running of factories, workshops and business enterprises, credit unions for business and manufacturing were established. In 1861, these unions had 300 members. There was also a special loan organization for artisans. A loan and savings bank was established in 1862, which had one million guilder in circulation during the first years.

There was already a hospital in the city in 1832. From 1852, there was a home for the handicapped with twenty beds, and from 1872 there was a general orphanage.

At the beginning of the 19th century there were 364 houses in the city, and the city property amounted to 683,623 guilder. There were 458 houses in 1883, 431 in 1893, and 554 in 1900. The regional court sat in the city, which employed two notaries, 26 lawyers (as compared to ten during the 1880s).

In the medical arena, there were two hospitals, three pharmacies, sixteen doctors, and four veterinarians With regard to educational institutions, there was a new national trade school for dairy farming, and an advanced school for girls.

The population grew during the years 1880-1921 according to the following table.

| Year | Pop. | Jewish Pop. | % | Catholic Pop. | % | Greko Catholic Pop. | % | Others | % |

| 1880 | 11,186 | 5,820 | 52.1 | 5,152 | 46.1 | 160 | 1.5 | 84 | 0.3 |

| 1890 | 11,953 | 5,462 | 45.9 | 5,862 | 49.0 | 162 | 1.4 | 437 | 3.1 |

| 1900 | 15,010 | 6.326 | 42.1 | 8,210 | 54.7 | 420 | 2.8 | 56 | .04 |

| 1910 | 23,688 | 8,783 | 37.1 | 13,872 | 58.6 | 951 | 4.0 | 40 | 0.3 |

| 1921 | 24,942 | 11,361 | 45.5 |