|

|

[Page 394]

1. A letter from Milek and Lunek Wolf – June 4, 1943 from the Janowski Camp (Lvov)

My dear ones,After terrifying events we are still alive at this hour. I will not describe the details. Mrs. Krisia was also here on Thursday, and certainly everything is known to you. I ask that you send us a bit of money and food through the MuKa”Z. The MuKa”Z sees Lunek every day and it is possible to send things through her. I tried to stay with Mrs. Griznau and tell her everything. Lunek and I have been hungry for ten days, and there is no help. We do not know how much time will be given to us here, please don't allow us to die of hunger. We are living in a purgatory that is worse than Dante's. It looks like I do not have to add and write more. We are begging you to extend assistance to us immediately.

Regards to those at home,

Milek, Lunek.P.S. Give regards to Jassa Schinner and ask her to send something for us.

|

|

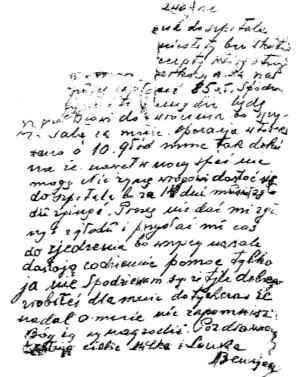

| A handwritten letter in Polish (No. 2) from the Janowski Camp in Lvov |

(Words of his younger brother Lunek)

[Page 395]

2. A letter from Benzion Wolf, from Zolkiew to the Pader-Uradner Ghetto in the Janowski Camp (Lvov)

The Aktion took place on Tuesday at 10 o'clock in the morning. Hunger oppresses me very much to the point that I cannot sleep, even at night. I do not praise the enemy for taking me to the hospital because in the course of 14 days, there was death here from hunger.Please send me some food and do not let me die of hunger. All those located in the hall obtain food every day, and I am the only one who gets nothing.

I hope that you will not forget me in the future because you have done so much good on my behalf.

May God reward you.

I send regards and kisses to you, Milek and Lunek,

Benzion

[Page 396]

3. A letter from Milek Wolf of Zolkiew sent from the Janowski Camp (Lvov)

Your first and second letters and the packages gave us great joy. Imagine what has happened to us because I do not want to extend this writing about things you already know. (Ad rem!) Most importantly we are alive, as you know, with our father, who has been badly affected, with Benzion who is in the hospital after an operation on his hand, and the rest of the family. Lunek and I have places that are not too bad. We work in the institution, and I earn 100, 200, and even 400 zlotys a day. Thanks to God that we will not know life in the camp. God supports our way.We have to get up at 3:30 a.m. At 4:30 a.m. we have to line up at the ordering place, and at 5:45 a.m. we leave the camp to do heavy labor all day, with only bad food. We return at 7:00 p.m. Up until 9:00 p.m. we wash, etc., and then go to sleep. We can buy additional items. We received 300 zlotys of the 1000 zlotys of our holdings from you, and it is with us. We need socks, oil, and sugar in whatever amount is possible.

Don't worry about us, think only for yourself. Unfortunately I do not have any more time to write, and I wanted to add more. I have to go to the doctor because of sores in my throat and a nail of mine has fallen out. Bolster yourself and take courage. Lunek will write to you in detail, and he is preparing a full letter.

As you already know, I work at the train workshops as a craftsman. I leave the Gehenna all day, and return at night. The oil was wonderful, and I enjoyed it.

We lived in the camp here for no purpose, and were it not for the food our lives would end; however, as you say, our family needs to seek vengeance, and that task falls to us.

I feel well. Hunger has not yet affected me. I am not in need of anything at this time, except what the young lady promises us every week. How are you? How is Moshe Mittelman? How come you do not send me a sign of life from you? Regards to Dorek, Rozha and everyone.

Kisses, and regards to you,

Lunek

4. A Letter from Zolkiew by Milek Wolf from the Janowski Camp

To my only sister Michal, beloved of all,We cried over your letter, Lunek and I. The thought gladdens us, that the master of the house looks after you and that you should remain alive.

[Page 397]

Our calamity is great, but we are not alone.Shayn'cheh dear, my heart bursts from the pain of the idea that I will not be able to see my only sister who I left.

Oy, these martyrs: our mother, Bruzya, Janek and the child, and the rest.

As for us, Lunek has written to you. I have gotten worse in the past two days, I have sores in my throat. Don't send things for all of us, leave all these things for you. Because I cannot look after you, it is difficult for me to bear the fact that you are looking after us. ‘Food for escape' I make every day, but I wait for things to get easier for you. Think only of yourself.

I met with Luska Wagner and I have communicated with her. I am hoping for appropriate help, and I will not write all of the details because my hands hurt. I am hoping we will see each other.

My address is:

Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle, ul. Korkow 23aRegards and kisses with all my heart

Milek

5. A letter from Lunek Wolf of Zolkiew sent From the Janowski Camp (Lvov)

Sunday, May 11, 1943

My Dear,I received your letter and the money today. We were so full of joy because until today we had not received any news from you. Sadly, the fate of all the Jews has not passed over us. In the evenings we sit and mourn our fate. But we take courage in one thing, that at least you remain. Milek works in the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle on ul. Listofa, and it is very good for him there. I work in a train workshop, in the heat of the hall machinery, and it is good for me here. The wife of Sztikhenberg is to be added here, since he works with Milek, and three days ago she brought us 1000 zlotys from Mrs. Griznau, a shirt, a towel, underwear and soap. Apart from this, we don't need anything. Don't send us money, since you have a need for it, and when we need some, we will write to you.

[Page 398]

As to escape, we can try every day, but to whom? Is this even possible, to you?The Gehenna is not so terrible when you imagine for yourself that we eat and drink many types of food (chocolate). Milek looks very good. Benzion is in the hospital. Our father has left him. Here every person lives for himself. I have the task of meeting every morning on ul. Idzhikowski at the corner of Janowski, from 6:20 - 6:40 AM, on the bridge, and again at the same hour in the evening. Fridek is in the Ghetto. I make an effort to get word from Mrs. Rudnik Wohlikh to you. Milek's square watch is in the oven above, covered in ash, you can take it. Let me know the address so I will be able to write to you. Is Moshe Mittelman in Zolkiew? Aleko and Shmuel are with us. I sold the moccasins and my shirt, but this is not important. I am writing this letter in the shop, and that is why it is soiled. Don't sell anything to Mrs. Griznau yet. I was in the Ghetto last week, and I ran into Salko Borer. He gave me 100 Zlotys for myself and another 100 for Benzion. Benzion does not have a cent, but we are helping him out. There are about 70 women here from Zolkiew. Among them are Tolda and her mother, Savka Schuman and others. I am writing randomly when it comes to my mind. Milek has a very nice place to work.

P. S. The men of the Gestapo searched our house from 6:00 a.m. until 12 noon. They turned over everything. The men of the Jewish Militia from Lvov found us, and Hinde Dagan fell into the trap along with us.

|

|

|

[Page 399]

6. A letter from Milek Wolf of Zolkiew from the Janowski Camp (Lvov)

Saturday

My dear ones,I have received everything in perfect order, and I thank you. It arrived at the right time. I ask your pardon for causing unpleasantness of this sort to you, and I will not send this anymore to anyone.

The camp is liquidating, and every day they cremate 200 to 300 people. The hours we have left to live are numbered. I will attempt to orient myself according to your guidance, and that will be today or tomorrow.

Lunek is going to remain, as it seems, in a barracks and will be relatively safe, but even this is temporary. I was already along the way, but I was turned back, and I happened to get away, to my good fortune, from a certain death.

The father of Philip Alko, Shmuel and Meir, Miszak Astman and 600 other people from Zolkiew no longer exist.

I received bread and fat from Rodska, and yesterday I received 3 kilograms of rye, and 3 kilograms of corn. Mrs. Griznau has to bring me money today, and I don't know how much. I will not be able to speak to Janek; there are things to tell. She is very nervy and strong-willed, and has already established connections with Oskar. I am writing while standing at work, which is why this is so bad.

When I get a chance to cross over, I will leave a letter with Mrs. Griznau, for you. What is going on with you, and how do you feel?

Be strong and gird yourself with all your might, in order that you remain alive and take revenge for all the insults heaped on us. Do not continue to send money, except perhaps for Lunek. He will enter the barracks in January, and it may be possible to obtain it through Mazurek, one of the workers on the train. He is a trustworthy man, and it may be possible to send everything through him.

I bought shoes for Lunek, and trousers for myself with a part of the money that I received,

Be strong,

Milek

[Page 400]

7. A letter from Genya Leiner to her brother Mundek

The following letter was sent in April 1943, during the last days before the extermination of the Zolkiew Jews, to Genya's brother Mundek Leiner, who was taken into the Red Army. Once she was sure that he was still alive, she left her letter in the hands of the assistant to the teacher, Teichman. In the past, she had also worked as an assistant for the Leiner family and after the liberation she turned over the letter to the Mundek brothers and Ziggy Leiner, who had returned and were in Zolkiew.

Dear Mundek,It was not my intention to leave this letter for you, but our mother is giving me no rest, and demands that I write several lines. I know that this will awaken excess pain in you, as our situation is so terrifying. When you read this do not shed even one tear for us. Back then, in the hour that we parted, I never thought a thing like this could happen to us, and instead of receiving you with a blessing, let us say goodbye forever. The situation is not one that can be found elsewhere. All of us Jews are sentenced to death, except that we do not know when the death sentence will be imposed, and it is anticipated every hour and every minute. The harassment continues ceaselessly, and we are pushed toward the grave with force and momentum. Do you have any idea of how terrible this thing is, to live and know that at any minute, that I, and my relatives, are destined to this? And we so much want to continue living, and to see you. We have not received regards from you for some time, and we were so happy when that happened! It will certainly be difficult for you to imagine that we were unable to find guidance, by whatever means, and perhaps to our sorrow, we could not find a way out.

Only non-Jewish friends were able to provide some help, and as you know, we left everything behind at this time of distress, and everything remained apathetic. Well, if God has abandoned us at this time of distress, what will we say and what shall we tell friends who endangered themselves by giving us help. We cannot delude ourselves, and we wait for relief to come to us, the death that will release us from this torture and suffering. We are an eye-witness to a huge tragedy. We see children pulled out of the grasp of their parents, children who are running around in the streets with no roof over their heads. They are naked and exhausted, and starving, and saw their mothers and fathers murdered before their own eyes. Or there are parents who do not know where their children have disappeared to, depressed and driven nearly crazy with worry. The trains take thousands of Jews to a place of permanent rest. The few who jump from the train cars in order to save their lives, and are shot to death on the spot, all of this engenders a loss of sanity and we begin to wonder if our minds are working correctly and if our understanding is clear at all. Even the sturdy among us have their spirits collapse.

As you know our father was a man of vigor and capability, an optimist who saw the world through rose-colored glasses. As of now, nothing is left from all of these intentions. He has become so sloppy and so backward in his will, he has lost all will to live, and he is willing his soul to death. However, this poor man needs to work hard because costs are rising and there are times when we do not eat for a week. And there are no exceptions, the cup had passed over all of us. And our mother complains to God that he does not make a miracle and she always implores God because he is so wondrous in making us suffer. She cries over you if she thinks she will not be able to ever see you again, and she cries over Zunya, and wants to know what will happen to him? And all of this repeats itself. And Zunya also suffers terribly. He is very enraged but he is dumb as a rock, too proud to complain

[Page 401]

for no purpose, and by his nature he is wrapped up in himself. He is so handsome and good. If you could only see how he works, and every cent that he earns he gives to his mother. My heart is torn and broken out of sorrow when I look at him. He is so young, talented and of a good heart, and all of this is supposed to go to nothing. I wonder to myself why my heart doesn't burst out of sheer sorrow. And as for me, my limbs are very weak. As of now, I am more restrained than everyone and sturdy in the face of suffering. After having suffered so much in my life, death no longer frightens me. It is as if every stone could shout and every blade of grass could speak, but enough of this. More important than anything else that I say to you, that if we should die, and one cannot discount such an event, I want you to take everything for which we have worked for so many years, and make sure it is not lost. I leave to you, all the signed documents, our parents' marriage certificate that may be of some use to you, also a list of various items that I am safeguarding with people I know, and also all your clothing that you will certainly need. And if God helps, as I plead before him, I will let you know the details on whom to bestow this task.Apart from this, I don't have anything else to add. I take my leave of you with great sorrow and an ache in my heart, and I wish for you that fate will tilt goodness and that what we have suffered will redeem you from all things bad, and if, God forbid, you will not find us, do not say you have given up. Take control of yourself and bolster yourself so you can live in peace. I advise you to sell everything and to go out to distant places far from this accursed place.

Be at peace and do not continue to worry, because time heals all wounds to the heart, and your pain will also diminish with the passage of the years.

With Blessings Upon My Family

Genya

|

|

| A family letter from Zolkiew sent with Gestapo approval (1942) |

[Page 402]

|

|

| The mass grave of the last of the Jews of Zolkiew at the Boork Grove |

8. A letter to Bernard Fachman, in a POW Camp in Germany from his brother in Zolkiew

Date: December 19, 1942, Zolkiew, Galicia

(Censor's Stamp of Stalag 80 III C)

Censored by Auflag 6, A, VII

To the War Prisoner Bernard Fachman, Prisoner No, 70762

Signed – Camp Commander – 9432 VII A Germany

17.12.42

To my precious and beloved brother,I am writing to you by myself, as you will see, and I will not be able to hide the great calamity that has passed over us in that our older sister has been taken from us. I will write to you and describe how this happened.

Four weeks ago, we were hit by a terrible windstorm that uprooted thousands of people, and only a few remained to flee. By a miracle, I remained alive, but what is in it for me? My dear brother, our pain is very great, and the tears flowed from my eyes, and my heart is broken from having gotten to this point. I remained alone without any other member of my family surviving. And so, my brother, be very careful. Don't be swayed into believing things in vain so that you may be able to wait for the coming of better times because I will not attain this. Every day, we wait for the onset of yet another calamity, because the circulating news is that not one of us will survive this time. And I will be added to our dear mother, to Golda and Anshel, and we will be together. My dear brother, please respond to me immediately, and perhaps I will receive yet another letter from you, and I will be able to see that you have received this letter from me. To this day, mail service does not work for us, for only today did I receive your letter dated November 8, 1942.

Translator's footnote:

[Page 403]

By Miriam Heller

On the following day, the final Aktion in which the Judenrat and Jewish police were liquidated took place, and was the Judenfrei Initiative. At that point, the ghetto was spread over a number of streets and my family and I were living in a corner house in the Taft house. They had stripped a number of the walls of bricks, and it was through this narrow passage, with hands flush against the body, we climbed up to the attic. After the Aktion began, it only took a few minutes for our hiding place to be uncovered.

A terrible moment arrived when our hideout was discovered. We had to slither back the same way we came, where armed Germans stood with weapons aimed at the heads of those emerging from the hideout. We stood in a line when they took us out of the hideout and other people were added from the remaining houses. We were chased along the way to the assembly point in the middle of the Synagogue.

The assembly yard was surrounded by Germans, and as people were brought in, the sound of gunfire was unending. They also brought the wounded, among them Astman (of ul. Lvovska) who was wounded in the Aktion immediately preceding this one, and was shot on the spot.

Everyone stood in the yard in silence. There were no screams or crying voices to be heard, even those being beaten did not scream. It was the silence that screamed.

I remember going over to my aunt, Wolf, who refused to recite the Vidui[1] before death. My group and I spoke silently. An observation was overheard: ‘the idea is terrible that soon there will be nothing left of us. Who will exact vengeance, who?’ Those seized were then ordered to place their valuables such as money and jewelry in boxes that stood at the edge of the yard. Whoever was able to, threw the money up above, or trampled it on the ground. Those who were suspected of hiding their valuables underwent a personal examination.

At a set moment, the Germans called out the young girls from the masses. After some hesitation (without knowing what their intent was), we exited since we had nothing left to lose.

I was among those who were called to leave, and we stood in a corner by ourselves, organized in sixes and ordered to sit on the ground.

The Germans appointed to keep guard over us, told us that we were not going to be killed immediately (and laughing, they stressed, immediately) and transferred us to the Janowski Camp. We watched how they loaded the people onto the freight trucks, and I saw the freight truck with my family disappear. I knew I would never see them again.

[Page 404]

After they removed all the people who were sentenced to an immediate death, the Germans came closer to load the people who were designated to be sent to the Janowski Camp, and they parked the freight truck at a bit of a distance. A sign was given and six men stood from the ground and ordered to run after the truck. Along the way, Germans stood with staves in their hands, and anyone that weakened in transit was beaten mercilessly.

They reached the row of young women. There were 89 of us. We were taken in the direction of ul. Lvovska, at the edge of the city. The truck suddenly stopped where the road split. The Gestapo men began to discuss what they were to do with us. Some said to send us also to where the previous lot were taken, and others said to send us to the Janowski Camp. In the end, they decided to return to the city to get the opinions of the officer-in-charge.

We awaited the results, and after an hour they returned and approached the truck and indicated the way to Lvov. We proceeded for several hundred meters and another truck joined us that was loaded with clothing and goods. I remember, when I thought of my dear ones that had gone their way, I begged that death would put an end to their suffering.

In the evening, we came to a camp, the 89 young women and I. I can only remember very few of the names: the Krantz sisters, Manusz, the Mandel sisters, Klara Schiff, Tolda Astman and her mother, Zimeles, and others. When we were already in the camp, we said: ‘what good is it to them, because whoever gets buried alive is not living anymore.’ Out of them all – I am the only one who remained alive.

Translator's footnote:

By Chaya Graubart

1. The First Encounters

Many times when I turn my thoughts to those terrible days of the Holocaust, I ask myself, how is it that I, a simple, unassuming human being, one of many, was saved from the murderers and the jaws of death. I still wonder and find it hard to believe how many times I stood eye-to-eye with death and was saved, literally, by a miracle, the only one of my family along with very few of the people of our city who remained alive. There are many images and memories that rob me of my sleep, and embitter my moments of happiness as they remind me of my beloved and my dear ones who are no longer here, who suffered from terrifying tortures at the hands of the murderers.

It is hard to describe the strong will to live prevailing in those days, the will to go on, to withstand and overcome the anger and ferocity of the despicable foe, to transcend the goal of the Scourge which was to denigrate the Jew through oppression. The Jews reacted with an enormous will that they could bear a ‘dog's life’ with whatever strength they had, without a house, hungry and tortured. And in their hearts, the spark and flame burned with the hope to survive and to be able to see with

[Page 405]

their own eyes, the end of those who were the Scourge and the exterminators of our people. Our innocent and honest brethren who were taken to their death did not know that it was futile to fortify themselves in order to live. The entire world, and even the Jewish people, did not learn how to evaluate the enormous suffering that had so marked the lives of all those who remained alive, who passed through all of the furnaces of Gehenna, for the sake of the living where hordes fought so much on their behalf.

The images from those days were etched in my mind with an ineradicable stylus and left deep scars in my mind and pain in my heart. This chronology of life was accompanied by suffering and terror, but from all of these simultaneous events, there are a few images that stand out and always appear in my memory, like a living nightmare. The eye and the ear absorbed the impression of events that were inhuman, even though the ones who perpetrated them were human beings themselves, and the mind is not set up to forget them. Among those bolts of lightning and sparks of memory, I hear echoes of the screams from the Tailor's Street on one of the pogrom days that took place against the Jews at the beginning of this travesty. For certain, this was not the most terrifying event that I lived through. Terror and suffering were the bread of my existence for many days afterwards, but the soul does not seriously ask which event was the most terrifying. The soul is wounded, the heart feels, and the mind does not forget. And yet, to this day, the screams that echo in my ears, and fill my head, are the screams that I heard from the Tailors' Street.

The incident took place in the first week after the invasion of the Nazis into our city, in 1941. The Ukrainian Nationalists were drunk with joy and lusted for revenge after the departure of the Russians. The Germans influenced the Ukrainians to come over to their side. A dark spirit of regression and impending fear pervaded the homes of the Jews. The first signs of what was to come were orders by the new authorities, who were brought over during the course of a few days by the Ukrainians and the Volksdeutsche, to prohibit Jews from leaving their homes. On this day, which was a Sunday, all the gentiles of the city, nearby villages and surroundings, assembled to celebrate the Nazi victory.

At nine o'clock in the morning the activities and demonstrations began, with the participation of the populace, especially the Ukrainian youth from the nearby villages of Wala Wysocka, Turynka, and others. The speeches were finished by noon, and at that point, the church bells began to ring in a rather frightening volume. In days to come it would become known to us that this was a signal to start the activity. At the sound of the ringing, the horde of young men, armed with canes and axes, ran from the center of the Rynek, the assembly point, over to the Jewish streets, Sobieska, Lvovska, Piekarska and the rest of the streets. We lived in the Rynek and we saw everything from the windows of our house.

When we saw the pandemonium we closed all our doors and put up barriers we had prepared behind them, but after a few minutes, the wild animals broke into our house, broke the doors with axes, and overcame all of our barriers.

The motto that they cried was, ‘cursèd Jews, servants of communism, go to work!’ And it was with these sorts of shouts that they took my mother ז”ל, my sister Chaya ז”ל and myself to the street. My father ז”ל succeeded in hiding in the cellar, and the house remained exposed to the abuse by the wild mob. The mob surrounded the Jews from all streets of the city, from the Schloss to the palace called the Zamek in which there was a provincial jail. They ordered the Jews to clean up the jail cells that were full of bodies of people who had slept there for several days. It was full of blood and secretions

[Page 406]

that the Soviets left behind when they left the city. The denigration of the Jews was terrible, they heaped murderous blows upon us for the entire way to the Schloss. One of the Ukrainians wanted to kick my dear mother ז”ל and I succeeded in covering her, and I absorbed the kick and also a slap in the face. I saw all our neighbors, near and far, and relatives around us who were also treated this way. Among the pandemonium, I saw the officers of the Herrenvolk with cameras as they were taking pictures of the scene.

Consumed by fear, pain and shame, we reached the Schloss above which hovered an icon of the Holy Mother. This was the assembly point. Pails of water stood here to clean the jail and the palace. The gentile women stood and laughed at us, and the thugs heaped cruelty upon us. Screams reached up to the heavens. I remember how my mother, sister and I were able to get away from the horde, which acted without restraint. We sneaked down an alley beside the Fishinsky-Rosenberg pharmacy, to reach my sister's residence in the Leiner family house, the owners of the candle factory, on ul. Niezwytowska. We wanted to go by way of the old garden to the non-Jewish street, to find refuge there. We were seized with fear and terror during our flight, and we heard the groaning and wailing, the residue of the cries from the Tailors' Streets, Szpitalna, Lvovska and even from streets that were further away. I was able to discern the voices of the Fukrad family, Salka and Rozhka, the family of Shimon Apfel and his daughters, the Lampeltz family, the Rabinovich family, the Kalkhman family, the Schneider family, and also many other voices of families known to me. These screams of fear came along with us to the stairs into the old garden. The screams were the proper expression for the human feelings of suffering, fright, and the fear of death. The screams penetrated my innards and etched deep wounds into my heart.

On the downward stairs from the garden, we encountered Balasz, a Ukrainian priest, who went with his daughter to see what was transpiring in the Rynek. Because I knew them personally I was emboldened to ask what their youths were doing. They calmly answered, ‘they are only beating, not killing. It is nothing and it will pass.’ Afterwards we discovered that they knew what was happening from the start and were on their way to view the scene.

This was how we reached my sister's house. We were trembling from fear and we cried over the bitterness of our fate. We worried about our father who remained in the hideout, and also, we were not certain that the hooligans would not reach us here. At five o'clock we again heard the ringing of the church bells and the anger of their sound. We learned that the hours granted to the thugs and the youth to remove restraints and to allow the wickedness that was in them, had finished. We returned home full of terror and fear. There we found a complete upset, everything of value was gone, but we were fortunate to encounter our father ז”ל who up till now, was in the hideout.

The storms of that day continued, They were not yet over. On that night, a fire broke out in Mocowski's pigsty, a man who lived in our neighborhood. Once again pandemonium and mass confusion took place, but they were able to extinguish the fire quickly. It was night already, and we sat in the house dressed in our coats, and we were afraid to sleep. Suddenly we heard knocking, and after them three thugs from Wala Wysocka burst into our room, and shouted: ‘Jüden, warum nicht Schlafen Ach?’ (Jews, why are you not asleep?) They robbed us of several items of value, and continued to add

[Page 407]

their abuse and pain. When they left the house we put out the light, and sat as we previously did, for that whole night. During the entire night we heard knocking and screams coming from the nearby houses.

This is how our chapter under Nazi rule began. More days of this kind were heaped upon us under the rule of Ukrainians and Volksdeutsche during the two years of the Nazi rule. But the screaming that I heard when Nazi rule was first imposed did not leave me for the entire time, and those screams gave me the strength to tolerate everything; to flee and conceal myself under even more difficult circumstances, between boulders, among scraps, underground in narrow holes, in hidden places, any place in order not to encounter those human beasts looking for prey.

2. The Appearance of the City After the Retreat of the Germans

The Soviets drove the Germans out from the cities of Galicia, including Zolkiew, in July 1944. I remained alive at a distance from Zolkiew, where I was overwhelmed during the first days. I cursed the liberation day, because it caused me so much distress. I was ashamed for having remained alive and to be able to lift my eyes to the light of day, but what is done, is done. I had no regrets. I knew that my entire family had been exterminated. I initially put off the idea of traveling back to the city of my past, because how could I go to a place that had been so bad. Every stone in it was stained with the blood of our dear ones. How could I lift my head in front of the eyes of the gentiles, who did not show a single sign of remorse for the shameful attitude they took towards us, even after the Holocaust. It was quite the opposite. They felt that they were fortunate in what had happened to us. They literally derived much pleasure from the fact that they pillaged our homes, inherited our things, and they enjoyed what they did to the Jews.

Yet, despite it all, I was alive. I also began to think about the possibility of encountering Jewish scions of the city who had survived by fleeing. As this thought grew stronger, it gave me the courage to visit Zolkiew and to meet Jews who had remained alive, hoping that I might find a cure for my soul among them. It is hard to describe how I felt when I entered the city where I was born, where my parents were born, and where I grew up. It seemed to me that I had entered a forest that stood witness to the horrors, and I was tossed to a place where beasts of prey slaughtered living people and feasted on their limbs. In my imagination, I saw these beasts of prey tearing the living people to pieces, and I could see the stains of the spilled blood before my eyes. It was a calamity to me that this was not a dream but the bitter and terrible reality!

The bloodstains could still be seen on the stones of the city in each step where I placed my feet. The attitude of the gentiles added a further insult. They saw each Jew as someone demanding the return of their plundered goods. The Jews were like icicles in their eyes. I felt bad in Zolkiew. I imagined that I was among the beasts of prey who were lying in ambush, waiting to attack me. And unfortunately, many of the survivors were slaughtered by the local murderers, not Germans. It is not possible to describe my emotions, but I will attempt to briefly describe the facts. The city was bleak. The destruction of the community and the Jewish culture stood was clearly visible. It was not only the living that they killed, but they even gave no rest to the dead. Uncivilized things were done in the cemetery. They took out the headstones, broke them up to make gravel and to pave roads, and left the fields as pasture for cattle. The smaller synagogues had disappeared entirely, and the Great Synagogue was torn down. Its remaining walls stood straight and shouted to the heavens about the evil and abuse that had been visited upon them. This was an historic Synagogue, centuries old, recalled for its splendor in

[Page 408]

our literature. Houses that were previously occupied by Jews on Rynek, Kolomyya, Lvovska streets, now had gentiles living in our homes, most of whom participated in our destruction, and we lacked the capacity to take vengeance. Vacant Jewish homes were robbed of everything, with wreckage left behind. Jewish homes inside the Ghetto, on Sobieska Piekarska, Turyniecka, Sznicraska and other streets, were practically entirely destroyed. We knew that our ‘good neighbors’ looked for hidden things, and bored into these houses that belonged to Jews like jackals, tore up the floors, tore down the walls, bathrooms, cellars, etc.

Few individuals remained from the large Jewish community, and they were wounded in their hearts and souls forever. I found those who were still alive: Melman, the Patrontacz family, Reitzfeld and others, who gathered in their houses.

After several days, I left the city of my past that I loved so much, with a broken heart, and a permanently wounded soul. I could not find a city in Europe that had a place for me. I found my home only in our Land, in the Nation of Israel, and I live in it, fearlessly, and standing tall.

By Rachel Kaldor (Eikhl)

|

My city in a strange land, you are dear to me, my city You have the glint of the morning dew, you have the beginning of my spring, You are a source of the History, Gaonim came from you, You have the splendor of a Synagogue, vibrant Jewish life.

And an active youth in you, torn from the Diaspora

My city in a strange land, what is your hostility to a city of exile

My city, a city of horror, what do you seek in the city of betrayal?

And therefore Zolkiew, my city, is wrecked and you no longer exist… |

[Page 409]

1. Witness Collection No. 1213[2]

By Giza Ptarniker

Born in 1924 in Nadworna

After we fled the emissary for Belzec, a small girl and I arrived in Zolkiew after walking ten kilometers, barefoot and half naked. An Aktion was already underway in Zolkiew. Together, we were part of a large group of refugees who were seized and brought to the square, where there were already other Jews assembled.

It is February 22, and it is cold outside. We sat on the square with the Zolkiew Jews for days and nights. The Jews gave us bread, and this was the first time we had eaten in four days. On the following day, they ran us to the trains, and one woman, Cyckes, the wife of a teacher in Zolkiew who was born in Tarnow, gathered the precious stones and money from all of the detainees and then redistributed equal shares to everyone, in order for all to be able to pay someone to save their lives at a time it might be required during an escape. We came straight to the issue inside the train car. We did not have the time for much rumination, because the distance from Zolkiew to Belzec was not great.

I jumped from the train with the little girl after we had traveled five kilometers away from Zolkiew. We went to the village to a farmer's house. He received us very heartily and fed us and gave us drinks, and held onto us for the whole day. At night, he showed us the way back to Zolkiew. I walked back to Zolkiew. The Aktion was over. I remained in the ghetto for six weeks. There was no hunger there, but the overcrowding was terrifying as was the typhus plague. The Polish populace got along well with the Jews. There were many jumpers, ‘parachutists’ as they called the Jews, who were saved this way. The Jews of Zolkiew willingly helped them. I have never encountered Jews like the ones in Zolkiew to this day. A Polish woman, the wife of the engineer who wanted to rescue me, took me to her house. The Banderovtzes[3] tortured us and pursued us in a terrifying manner.

The Archive of the Jewish Historical Institute

(Signature)(Signature)

T. Bernstein

Consistent with the source. Signed: T. Bernstein

Translator's footnotes:

[Page 410]

The process of obtaining witness accounts:

|

I no longer had parents in March of 1943, and I lived with my husband in the ghetto. After the last Aktion of the camp occurred, there were only a few women, old people and invalids who were still there. We sensed that the days of the ghetto were numbered. During the Soviet rule, my son made the acquaintance of a Polish woman with whom he fell in love. This woman wanted to save our entire family. She lived under very difficult conditions, not far from the ghetto, with a woman named Sokolova.

Her brother-in-law advised her to take Jews into her house and hide them, to improve their situation. Sokolova agreed, and my brother built a bunker in her stable. She lived on ul. Turyniecki in Zolkiew. There was a horse and a cow in the stable, a sty for pigs, and rabbit cages attached to the walls. We felt more secure with all of these animals around us. The bunker was underneath the pig sty. The entrance to it was through a shelf on the floor that was covered with feces. Five people slept in the bunker, all on one side. When one of them wanted to turn over onto the other side, it was necessary for everyone to turn over, as if ordered to do so. One could only sit bent over. But we had electric lights that my brother had repaired. The highlight event at the time we fled from the ghetto, was the arrival of a German committee from the city of Lvov, which looked for an appropriate place to murder Jews by gunfire. We began our life in the bunker on March 22, 1943.

Many people in the town know of the connection between my brother and the sister-in-law, and they guessed that she hid him. I, and others, did not know. Someone informed the Germans, and they looked for my brother several times. We had to create a false-front story. My brother wrote letters, and Sokolova's daughter traveled to Zhitov with the letters, in order to mail them from there to create the impression that he really was in the camp.

|

|

| An accompanying Polish letter from the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw regarding the transfer of the witness accounts |

[Page 411]

After a while, the sister-in-law put on a face in front of the neighbors, as if she had received notification that my brother had died, and for several days, she walked around crying and with tears. Despite this, many details of the truth came out about her. The neighbors followed her around and paid attention to the fact that she bought food in large quantities, more than for only one person.

Once the Ukrainian policemen encountered her while she was preparing food packets, and they saw that the large number was more than needed by one person. They jumped on the hayloft and called out: ‘Come out, Jews, come out!’ They walked about, knocked, searched, but they did not find the floor covering that masked the entrance to the pig sty. The floor covering was always closed from the center side, and open on the second side. There was always a guard there who saw everyone who entered the yard. We, Sokolova and the sister-in-law had agreed-on passwords and also bells. We were silent rabbits. When the sister-in-law called out: Trusz-Trusz, this was a signal that the danger had passed. We also had melodies we agreed upon. One tune had the meaning to conceal, and another tune indicated that it was now possible to come out. Apart from this, the barking of the dog warned us when a stranger was coming near. Despite all this, there were instances when there was a lapse among us and a mishap. Blumenfeld was sick with Typhus and he was constantly coughing. One time, a strange farmer came who wanted to see the cow, and Blumenfeld could not contain himself, and coughed. My brother had a friend, Timofiyev, with whom he discussed going over to the partisans. After a while, Timofiyev received an order to go to the S.S. Without foreknowledge that she was the one hiding my brother, he told the sister-in-law about it, who one day drank too much and came together with a Volksdeutsche to look for Jews inside our premises. We were convinced that we were lost. For the first time, Blumenfeld had a hemorrhage, and from then on he spit up blood continuously.

We knew, only too well, that he was the source of contagion by a terrifying sickness, and all of us were sentenced to breathe the confined air that he also was breathing. We all armed ourselves with poison and grenades, so that in a fateful hour, we would be able to exact revenge and die. One time Blumenfeld was standing by the entry and did not pay attention to the people coming close to us. This was the lady of the house, and the Ukrainian informer named Bacz. When Blumenfeld saw them, he lost his mind and jumped onto us through the floor entry, and in this way, he revealed our hiding place. But a miracle happened. Bacz did not betray us, he said to the sister-in-law that she should not worry, because from the vantage of ‘watch out for me and I'll watch out for you,’ he would help her now, and it could be that a day will come that she will be able to help him. People at that time were already thinking of the possibility that the Soviets would arrive, and they wanted to leave themselves a way out.

Incidents like this, and others like them, happened all of the time. Someone would see a head appear, another might cough, or sneeze in front of a stranger non-resident. Blumenfeld's illness became more severe with each passing day. The sister-in-law turned to the Ukrainian doctor Kupistianski and told him everything. He was taken aback and became frightened to his heart, because in the entire surrounding area, there were rumors of Poles being imprisoned for hiding Jews. Despite this, he did not withhold help and gave injections and medicine to the patient, all with no charge. The sister-in-law cooked for us, and brought food into the stable in a pail covered with a rag. Many, many people inferred that there was something clandestine going on here, but to our good fortune, none of them informed on us. We had many difficult moments. There was a Jewish cemetery not far from our hideout, and we heard the sounds of gunfire from there, and the screams of Jews who were removed from their hiding places and murdered.

[Page 412]

One woman asked to have her neck broken so that she would not have to look death straight on. Another woman asked to be shot all over her body, just not in her head, because she did not want them to damage her face with gunfire. On one occasion, a mother was brought with her two children. She asked to be killed first because she did not want to see her children die.

We had contact with Jews in the forest who sent necessities to the sister-in-law so she could exchange them for food. One time some Jews were grabbed, and the sister-in-law saw how they were all being taken to the torture place. We feared that they would turn us over to the Germans because the Germans tortured those they captured so people would disclose the hiding places of others, but they did not reveal where we were.

The Soviets entered in July 1944. The first of the shrapnel set fire to a doorway entrance close to ours. Our condition bordered on giving up. To go out? The Germans were still in the city, but to stay hidden, that meant being buried alive. The sister-in-law stood on the roof and by herself started to put out the fire, paying no attention to the hail of bullets of the spreading battle. Others helped and succeeded in containing the flames.

Witness signature: Rachel Zimand

Protocol written by: Ida Glickstein

The Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute

Aligned properly with the source (Signature).

Signed by: The Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw

By Joseph Hochner

His parents were well-to-do lumber merchants. He finished seven classes the elementary school and a course in commerce. He was an expert in the technology of trees (from Main) and up until the war, he worked at this profession. He continued to work in his field under German supervision at the beginning of the conquest, and afterwards, in concert with the direction of the authorities, he was released from this type of work because he was a Jew. He lived in Wroclaw, as a storekeeper. He has no one. He lost all of his family in the conquest. During the time of the Aktion in Zolkiew he was seen to be Enlightened. He relates his experiences and the tales of the ghetto in Zolkiew in an artistic manner, even though he tires quickly. He makes lists in his story, to lay out the events in a chronological order.

1. The City of Zolkiew

The town of Zolkiew, like many towns of the East in the past, had a Jewish character. Approximately 7,000 Jews who lived in Zolkiew were mostly craftsmen and retail merchants. They were a backward element, very religious and fanatic, who believed in miracle-working Rebbes, Tzadikkim. The well-to-do aristocracy was a large group of working intelligentsia, and there were wealthy merchants, some of whom were Hasidim.

[Page 413]

At the onset of the conquest, the population grew by one thousand Jews. These refugees were from Warsaw and the provinces of western Poland, areas that had already engaged with the Germans and saw the denigrated life that awaited them in the country of Hitler. They did not know that a tortured death awaited them, a death that was quite fast in coming. They also did not want to believe any of it, even when someone with insight on the issues explained the facts to them. Immediately after the onset of the conquest and the liquidation of the small Jewish settlements in the area, a stream of 4,000 Jews reached them from Mosty'-Wielki and Kulikovo.

When the conditions in the Zolkiew ghetto worsened, approximately 600 Jews fled to Mosty' since at that time there was a more tolerable labor camp there, and the food was better.

There were no illegal escapes to the Soviet Union. It was very difficult to get out of there with the use of Aryan papers. In the surroundings of the little town, in which everyone knew everyone else, there was no lack of informers. The Germans did not impose prohibitions on the populace, but sanitation conditions and access to food were very difficult. This constrained the number of births, and a swift death came here easily.

During the Typhus epidemic close to 1,500 people died. A day did not go by in which there weren't 20–40 funerals.

At various times, about 10 Jews from Austria and Czechoslovakia came to Zolkiew. They largely came alone, and at the beginning their condition was much better than that of the local Jews. The Germans did not mark them at the start, and the Germans gave them a variety of tasks. A number of them were exterminated during the time of the Aktion in the ghetto. The remainder were sent to the Janow Camp. Not one of them was rescued, not even Max Schlusser from Vienna, who enjoyed special privileges from the Gestapo due to his ability to see the future. Even the Gestapo people, regardless of their status, and their wives and loved ones, took advantage of his forecasts and advice.

2. The Relationship to the Jewish Populace During the Conquest

The Germans treated the Jews of Zolkiew in the same manner as they did to the Jews in the entire area of conquest. Beatings, plunder, abuse and murder did not cease for the entire time. The local authorities exceeded that which they were required to carry out, and it was the local authorities who asked the Germans to erect a ghetto, and afterwards, to speed up the Aktionen to exterminate the Jews. They wanted Zolkiew to be a purely Aryan place of residence. The local populace of Ukrainians and the Volksdeutsche organized militia divisions to facilitate the orders of the German leadership. They seized those who fled the ghetto. Their emissaries went through the city and turned the Jews over to the Gestapo. In general, however, they murdered Jews on the spot.

[Page 414]

3. The First Methods of Oppression

The first act by the Germans, the ‘carriers of the culture,’ was to burn down the ancient Synagogue. The Germans burst into the Synagogue, which legend says was established by King Sobieski, and stole anything of value. They unrolled the Torah scrolls, threw them on the floor and trod on them with their feet. Afterwards, when they were drunk with victory, they poured benzene into the Synagogue and set it on fire. The Synagogue was on fire for two days. The fire also consumed the Jewish houses in the area.

On the following day, the head of the city of Czerfolowiec became the commandant. His first act involved giving permission to conduct a pogrom. He encouraged Ukrainian thugs of the Black Hundred, who wore yellow and blue armbands. They first entered the church and after they received the blessing of the local priest, went out in order to run amok. The pogrom lasted for three hours. The sound of smashed glass, the wild shouts of the Haidamaks and the wailing of desperation of the beaten Jews was heard on Jewish streets. At five o'clock the pogroms ceased with the ringing of the church bells by the priest.

The Judenrat was created the following day. That council was given quotas of work to be accomplished, and they were required to enforce the many orders of the Germans: the donning of armbands, the prohibition to be out of doors after seven o'clock, the prohibition against forming a group, the prohibition against entering the park and ul. Mickiewiec, the prohibition to walk on the sidewalks, and the order to turn over bicycles and radio sets. After this, a Commission of Jewish doctors was established. The Jews were divided into three categories. The third category was for those who were ill and could not work. You can appreciate that wealthy Jews used bribery to attempt to be assigned to this third category which protected them from going to work, and abuse. On June 30,1942 a community-wide fine was levied against the Jews in the amount of five kilograms of gold, 150 kilograms of silver, and one half-million Zlotys. In order to assure that this payment would be made on time, the Germans detained ten hostages, among whom were Pust, Sobl and others. After receiving the required contribution, the hostages were released. On July 1, they arrested the members of the Komsomol, M. Hamerman, H. Hamerman, and L. Kraus. Those who were arrested never returned.

From that time on, the Germans frequently visited the office of the Judenrat in order to receive gifts, and they deluded the Jews into believing that this would save their lives.

In addition to the monetary ‘taxes,’ the Jews were compelled to turn over all their fur coats. The Judenrat set a daily quota of Jews, in the first and second category, for heavy labor, some of whom were sent to work on the roads. Every German who passed by thought that part of his obligation was to beat or curse the workers.

The Jews in the second category of workers were generally assigned to work in the barracks where they cleaned horses, cattle, vehicles and tanks, and cleaned up yards and toilets. Other Jews in this category were sent to the Stoykewiec building, under orders by the Commandant, where they were physically assaulted and mocked. All these groups returned to the Ghetto after work. There were approximately 10,000 Jews in the Zolkiew ghetto. There were two additional groups who lived in sheds in Wiezenberg, which was ten kilometers from Zolkiew. There were a thousand men who worked there in the fields. All of the cattle there had to be turned over to the Volksdeutsche.

|

|

| From the eyewitness account (Polish) of the witness Joseph Hochner |

[Page 415]

On October 25, 1942 the ghetto was organized in accordance with the order of the German authorities in Zolkiew. The ghetto was surrounded by a barbed wire fence and was bounded by Turyniecka, Snicarska, Bazilanska, Sobieski, Dr. Reich, Gansza, Piekarska, streets and a few more small streets.

The windows and doors of the houses on the border that looked out onto the Aryan side of the fence were closed and covered with barbed wire. In a short period, the non-Jewish residents were removed from these streets, and about ten thousand Jews were placed in this area. Other than the Volksdeutsche, the Aryan populace was forbidden to enter the ghetto, and the Jewish residents were forbidden to leave it. The ghetto shrank after the Aktionen, and by March 25, 1943 the boundaries of the Ghetto were compressed with only ul. Piekarska serving as a boundary.

Five men served in the Judenrat. Dr. Rubinfeld was appointed as the chairman. Apart from these individuals, other people in service were designated as organizers, and they wore hats with a blue band and also yellow armbands. Yegor Hamiur was an especially thorough organizer. He dealt with the plunder of Jews that was hidden in the bunkers, and afterwards turned it over to the Germans.

The practical language used for communication by the Jewish leader was Polish. The Jews had no use for courts. Within the ghetto, the cellar was used for storage and also served as the place where everyone met who had been given an assignment.

5. Economic Life

The Jews in the ghetto had a weekly food ration of a quarter of a loaf of bread, ten portions of sugar, and grits with gravy. The Jews received special cards which were used to obtain necessities in the Jewish stores. As this quota was not adequate, everyone tried to get additional food through other means, especially by bartering remaining valuables for food with the Ukrainian populace, carried out through the barbed wire fence.

The Judenrat operated a kitchen which gave midday meals to the poorest of the people. The Germans created a fur processing factory within the ghetto boundaries. The German authorities dealt with issues of the Jews through Jantz, the Landeskommissar regional commissar. The advisory council of the Ghetto and the organizations it created, exhibited the characteristics of assistance and charity-institutions. As it was difficult

[Page 416]

to acquire adequate amounts of food, the Jewish populace became impoverished and disease spread. In addition to the kitchen for the poor, the Judenrat also ran a hospital, an old-age home, and an orphanage. These organizations manifested a special concern for the jumpers, the Jews who jumped from the trains on the way to Belzec. When the Jews realized that the trip to Belzec meant extermination and not a work camp as promised by the Germans, many people tried to jump from the train during the trip. Jews kept knives and chisels with them which they used to cut an opening through the ceiling or wall or their train car to make an opening for escape. Despite the fact that the train cars were guarded by the Gestapo, people jumped in droves. They preferred death under the wheels, or by a guard's bullet instead of a certain death by poison gas. By jumping, there was a trace of hope of a chance to be rescued. The jumpers who succeeded in their escape were saved in the Zolkiew ghetto, the place through which all of the detainees on their way to the camp passed through.

There weren't any schools in the Zolkiew ghetto. The wealthy taught their children at home. The pressures of living in the ghetto and the difficult struggle to stay alive were not alleviated through satisfaction from cultural life. There wasn't an independent underground movement in the city, and therefore, no connection with underground movements in other ghettos or with the underground movement on the Aryan side. There were two Rabbis in the ghetto. One was Rabbi Rimmelt, who came from the United States, and there was also a local Rabbi, Abba Rabinovich. For some period of time there was a secret house of worship, but the religious Jews generally congregated in small groups in ordinary houses in order to pray together. The single convert, Bass, lived outside of the ghetto for a long time. However, when he began to run a substantial merchandise business with the ghetto, he was informed on by his Aryan competitors. He settled in the ghetto and was killed in one of the Aktionen. There were no trained organizers or prominent personalities in the ghetto who could step up to be the leaders of the distressed masses.

6. Liquidation of the Ghetto

The liquidation of the Zolkiew Ghetto took place in stages. All of it was orchestrated to carry out the unquestioned extermination of the Jews.

It was on February 2, 1942 that the seizure of Jews in Zolkiew began. Sixty Jews in the third category, that is, those not fit to work, were selected, gathered together in the school building, loaded onto train cars, and transported to Belzec. After this it was quiet for several months.

Typically, after these operations, the Germans promised those who remained alive that this would be the last Aktion. On November 22, 1942, the Ghetto was surrounded, a mass murder took place within it, and 2,500 Jews were sent to Belzec.

On March 15, 1943, the Germans ordered that all men from age 14 to age 50 were required to assemble on the field in front of the Judenrat, when they were shaved and dressed in clean clothing. These men were promised that this was not an Aktion, but an arrangement for a new contingent for work.

[Page 417]

A crowd of about 750 people assembled on the field at the designated time. A German gendarme addressed the gathered crowd, and announced that the men were to line up in rows of four, and go directly to the municipal building where they would receive their work assignments. They walked this way in their rows until they came to the sports field where they were immediately surrounded by the Ukrainian police. The men were ordered to kneel, and they remained that way for hours, until a vehicle with Gestapo soldiers arrived from Lvov, escorted by ten freight trucks and trailers. An order was given to divide up everyone into groups and load them onto the freight trucks. The prisoners climbed into the trucks, looking wretched, beaten and pushed around. They were surrounded by S.S. men and, as was later clarified, they were taken to the Janow Camp. From the total number of Jews so grouped, von-Papa chose seven men, among them this writer, and ordered that they be brought to the Ghetto.

After several days, on March 23, 1943, the Germans unleashed the largest Aktion in the ghetto. During that day, they transported 3,500 men to the Boork grove, a distance of three kilometers from Zolkiew, and murdered them all. From that time on, the Ukrainian populace demanded that Zolkiew should be free of its Jews entirely. And so, on April 6, 1943, the ghetto was surrounded, and that night the final decisive extermination began. One-thousand-seven hundred Jews were murdered. This was the final Aktion that totally liquidated the Jewish settlement in Zolkiew.

A small group of only 50 people remained alive. Von-Papa announced that this group of people will be lodged together and work. If it happened that any member of this group escaped, the entire group would be liquidated. If a stranger was found among them, or if one of the members of this group provided aid to concealed Jews, the entire group would be shot to death.

Twenty-five people worked with sorting belongings that remained after the Jews left. Ten men were designated to carry the corpses to the cemetery, and ten others to drive the dead. Five men were given the task of looking after order in the block. I remained with the last of the ghetto residents and worked in the burial detail. We worked each day, and at night, we discussed how it might be possible to be rescued, as it was clear that after this task was completed, all of us would be murdered.

The work of cleaning up the area, accounting for the assets and the bringing of additional victims to be buried, went on for several months. Every day the Germans and Ukrainians searched for Jews hidden in bunkers, and they shot them in the cemetery. One night, a group of 28 men, including me, decided to escape, which we did on July 10, 1943. Those who remained in the block were liquidated. And from this, one can conclude that on the day of July 10,1943, all the Jews in the city of Zolkiew were wiped out. Along with two women, I hid with a farmer we knew, who allowed us to remain in a hideout in exchange for payment.

At night, we dug a pit in the stable, 1.8 meters by 1.5 meters in size, and lined it with boards, and the three of us hid in that pit. Every day, the farmer brought us food and related what was going on in the world. We spent 18½ months in this hideout, up until the liberation by the Red Army.

[Page 418]

In addition to the three of us, approximately fifty people were able to hide in bunkers on the Aryan side. Most of them were saved, and were privileged to see Liberation Day by the Red Army. The wealthy merchant, Zaft, had constructed a bunker in his store, and he hid there with his family. The store was run by a former servant who brought food to the family in hiding. One day, there was a gendarme in the store, who detected the entry to the bunker, and was drawn to it. As soon as the elder Zaft saw the German, he grabbed a steel rod and struck him but he did not kill him. The German fled and called for the police. When he saw that the situation had no way out, the father took a shaving razor and murdered his family, and afterwards he committed suicide.

Signatures of the attesting Witnesses: Joseph Hochner, Yitzhak Lerner.

Transcriber of the protocol: Barszininska.

Proof of Transcription Integrity: (Signature)

Signed by: The Archive of The Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw

[Page 419]

By Michael Melman

At the beginning of 1942, the Jews of Zolkiew had not yet experienced the terror of the German Scourge whose actions to exterminate the Jews of Poland were already in full swing. Yet, the Germans had already implemented the first Aktion in Zolkiew, and news had reached the city from eyewitnesses who saw, or heard about the hordes of Jews removed from nearby towns and transported to extermination camps. The first Aktion in Zolkiew was symbolic of those to come after it. Even after sixty Zolkiew Jews were taken to Lacki, near Zolkiew, the atmosphere in the city was not one of desperation. The people of the town still hoped for a good outcome and even paid significant amounts of money in the form of bribes to the Gestapo men in Zolkiew and to the officials in Lvov. It was thought that these bribes, consisting of money and gold, did their job because the enemy did not assault the town. However, it became clear after a number of months, that this respite was only a calm before the storm. By March 1942, an order had come from the Gestapo authorities in Lvov to gather all of the Jews who were listed as limited in their ability to work, and to transport and detain them at the Belzec Camp. This action was publicized as if the people were actually being taken to a labor camp, but the real purpose was concealed. A non-Jewish citizen of the town who was sent to Belzec to trace the detainees disclosed the ordeals and terror imposed on these Jews, and the fact that this labor camp was actually an extermination camp.

In the aftermath of this German deception, the Jews of Zolkiew realized that the payments and valuable gifts only deferred the end but did not eliminate it, and the feeling of peace was only temporary. The Jews of Zolkiew were confronted with the knowledge that their turn had come to face a future of danger and tribulations like those already experienced by their brethren in neighboring towns.

[Page 420]

At that time I was working in a grain-oil factory. Before the German conquest, the factory belonged to us, and it was transferred to the economic organization of Ukrainians called Syuwisz. I worked together with Meir Berisz Schwartz in this factory. We were the only Jewish craftsmen employed to do this. Accordingly, we had the opportunity to help out the needy in the city, and especially to provide necessities secretly to the community kitchen that had been created in the town by the Judenrat. We would sneak items to them through a side door at the end of a work day, but we could not depend on continued success as these sorts of activities became known to the authorities.

Three Ukrainian police appeared at our workplace one day, at the behest of the Gestapo, and demanded that we follow them. They took us to where we lived and carried out a very detailed search, but did not find anything that would cause them to be suspicious of us. From there, we were taken to the police station where we were accused of taking necessities from our workplace. Thanks to the involvement of the Ukrainian Chief of Police who knew us, and was a friend of the Judenrat member, Dr. Shtraich, we were let go.

The atmosphere continued to worsen. Train cars loaded with Jews from Polish towns sped through Zolkiew on their way to Belzec. We no longer had any doubt in our hearts regarding the fate of the people on the train. We were relieved that there were some brave-hearted souls who were able to jump from the death-trains before they reached their destination. They told us about the systematic liquidation of the Jews from their towns. The atmosphere of distrust that surrounded us grew stronger. Both oppression and hope beat together in our hearts when the desperate ones saw the beginning of the end in the two Aktionen that were conducted in Zolkiew. The Judenrat members supported the idea among some people that a miracle would occur in Zolkiew, and within the constrained limits of the Aktionen, their lives would be spared.

Despite the difficult situation, and perhaps, actually because of it, the question arose among the Jews as to where to conduct services and assemble for a minyan for the upcoming High Holy Days, given the limits placed by the Germans on the Jews of the city.

My father's neighbor, Zalman Britwitz, decided that our house was the safest place to conduct prayer. Then we had to figure out where we would obtain a Torah scroll for the service. All of the synagogues in the city, particularly the Great Synagogue, were destroyed, and all of their Torah scrolls had been sacrificed on ‘the altar.’ My father told us that he had saved one single Torah scroll before the Nazis entered the city. As a God-fearing Jew, my father feared the possibility that the legacy of many generations would disappear into oblivion, since that was what the German Scourge had decreed. The story of the liquidation of Torah scrolls in other towns gave him the personal courage to take a Torah from the Zidichov Kloyz and hide it in the house of Yoss'leh the wagon driver, who lived nearby. The scroll he took had been donated by the Patrontacz family to the synagogue.

A few days before Rosh Hashanah, my father stealthily took the Torah scroll from the house of Yoss'leh the wagon driver, and wrapped it in his prayer shawl to carry it to our house. This matter was not accomplished easily. A German guard who happened to cross his path almost put an end to the success of this heroic deed. My father's faith prevailed, and he reached home without trouble. He donated the rescued Torah scroll in honor of his success in carrying out this mission. This Torah was destined, once again, to practically be consumed by a fire that broke out much later in the square of our house where we were hiding in our bunker. Again, a miracle from heaven came to us. Through this miracle, the fire stopped before it reached the place where the Torah had been hidden.

[Page 421]

News began to reach us in October 1942 concerning the cruel deeds perpetrated by the Nazis in the nearby city Rawa-Ruska and the town of Magierow. This news created an atmosphere of apprehension in our town, as everyone began to fear for their families and themselves. People began to think about ways to be safe ahead of the encroaching evil. My friend, Yehoshua Indyk, was a member of the Gestapo created Jewish militia, but he was always willing to provide advice and help. One day he came to my house and we learned from him that the situation was very bad, even worse than we had thought. He suggested that we prepare a hideout in one of the cellars. I spoke secretly with our neighbors, the families of Schwartz and Patrontacz. We decided to turn one of the storage areas of the oil factory that belonged to the Patrontacz family into a hideout. We went to work on this immediately, day and night, instead of going to our jobs at the factory. After a few days it seemed that we would be able to use the pit that we had dug for our purpose, but there was a problem.

We realized that our plan for using this hideout would not suffice. The Germans would suddenly close off the streets in which they had planned their Aktionen, and seize anyone who happened to be in their way. Because of this, we could not use the bunker we created because all the paths to reach it passed by the eyes of the German guards who would be carrying out the search.

|

|

| A Torah Scroll saved from the Great Synagogue going up in flames |

We kept pushing to find a location for a bunker. After the Schwartz family with four people, and the Patrontacz family consisting of three, had moved into our house, we decided to make a bunker in our home. We needed to find a skilled carpenter to open up an entry in the wooden floor of the room so we could descend to the cellar and hide in our hour of need. We were not anxious to hire a Christian carpenter in case he would turn us over to the Gestapo. I remembered a Jewish carpenter in our town named Shlitin, an honest, God-fearing man, who was willing to do the work, and he took on the task of making the structural changes in the house. He worked that whole night, and we stayed with him to help. With the coming of dawn, the entry into the cellar was finished. Shlitin remained as a guest in the house until morning because we did not want him to be in danger as he traversed the streets during the curfew hours. Later, he returned home unharmed.

This is how the bunker was erected in our house. We added improvements and repairs, in order to weather a storm when we needed to. We kept silent for a while, and hoped with all of our hearts that this hideout could provide us with a secure refuge. The bunker increased our sense of security in the face of danger.

[Page 422]

|

|

| The Melman house in which there was a bunker |

We occupied the bunker for the first time on November 22, 1942. This took place after Mundek Patrontacz, who had left his house to go to work as he did regularly, ran back and told us about an Aktion that was about to take place in the city. We had enough time to warn the neighbors and as we entered the house, we immediately saw that there were Gestapo men approaching. We ran to the bunker with the children, and it didn't take long before we could hear and sense the steps and presence of the Gestapo and their accomplices, walking around upstairs in our house. There were ten of us in the bunker, and we spent forty-eight hours in it, which seemed like forever. This was a test run for our ability to use the bunker for real, and we emerged with the clear knowledge that without it, we would certainly fall into the hands of the Gestapo.

The Germans had already vanished when we emerged from the bunker, but their trail did not disappear with them. They took our valuable items with them, and things of lesser value were broken and strewn about the house. We appreciated the extent of the miracle of our survival afterwards when we found out that hundreds of Jews were taken out of Zolkiew during the Aktion, in a direction to which we were not yet aware.

Our town of Zolkiew had emerged from its tranquility. Tens of families in the town ran around in hysteria in order to find their kin, and even I took part in the searches. I discovered that my father was among the people who were struck by the bullets of the murderers. He took his last breath in the Palace courtyard, the place to which the seized people were brought during the Aktion.

I was shaken up a second time when I returned to my house and my wife told me what happened to her while I was gone, and she was alone with our eight-year-old son. A Gestapo man entered our house and was surprised to see that there were still people inside. He asked my wife where she was during the Aktion, and she told him that she had been outside. Without thinking much, he pulled out his revolver, aimed it at my wife, prepared to finish the Gestapo work. But my wife grabbed my little son, clutched him to her heart, and told the German that if she was to die, let her son die also, and begged him to put an end to his young life. The German must have had some feelings of compassion which suddenly overpowered his sense of cruelty. He thought a bit, then returned the revolver to its holster and left the house.

[Page 423]

The pace of construction of the ghetto in Zolkiew had now reached its peak. The Jews had no recourse and were forced into the ghetto. We had to decide if we wanted to enter the ghetto or find another solution. My wife stood fast on not changing where we lived for any other place, and perhaps for the sake of this double miracle that had already taken place in our house, we stayed there, and we felt we would not be removed.

One day, a Christian man from the town appeared at the house. He was a Volksdeutsche by the name of Valenty Beck. He was in wonder for having found us in the house in view of the fact that the rest of the Jews had already been transferred to the ghetto. He explained to us that he was supposed to take over this house as his own. My wife was steadfast in her idea that no one was going to take us out of our house, and she went so far as to say she would prefer to be buried with her family beside the tree in the front yard than to leave. It appears that her words reached the Christian man's heart. After some thought he let us know that because she was so determined to remain, he would not demand that we leave, and even went beyond this by saying that he was prepared to act on our behalf in order to assure our security in the house.

His offer to help inspired us to have faith in him and we no longer feared him. He had heard that other Jews who did not go to the ghetto were hiding in different places in the town, and he asked us if there was a secret hideout in the house. We revealed the location of the bunker in our house, and consulted together with him on what to do in order to assure that hiding us would succeed. He was concerned that the Christian workers in our factory would know about the entire matter, and he decided to spread a rumor that we had abandoned the house and went to the ghetto. We told Mr. Beck that our group consisted of our family of three people and the four person Schwartz family. He agreed to this, and he was even willing much later to add the members of the Patrontacz family, and together we numbered ten people.

Mr. Beck, his wife Yulia, and their daughter Aleh, aged 18, came to live in our house. They took possession of the entire structure and its belongings. From that time on we never left the house, and it appeared that we no longer lived there. We agreed with the Beck family that we would be responsible to cover all the expenses for our sustenance. With the consent of the Beck family, later on, the widow Klara, the sister of Mundek Patrontacz who left the ghetto, joined us. We continued to live in the bunker this way for several weeks, and our numbers grew. Rahla Reitzfeld, the sister-in-law of Salka Schwartz, joined us. Rahla's husband was a policeman in the ghetto. However, after a few weeks she decided to leave us and return to the ghetto to her husband as she found out that he was sick. Others joined us in the bunker; Lula Elifant, who was a family friend, and also Artik and Kuba, two brothers of Mundek Patrontacz. These two had fled from the labor camp at Mosty'-Wielkie. After several months, Mr. Beck personally brought the Sztekl couple, owners of a pharmacy, to stay in the bunker.

One afternoon, two of the children of Salka Schwartz showed up at the house. After their parents were taken by the Gestapo, nine-year-old, Zigu Orlander, decided to take his four-year-old sister Zusha, to look for his family in our house. Their arrival created a quandary and worry by the Beck family, because the arrival of the children could have revealed the hideout. The boy begged for mercy to be shown to his little sister and not drive her out. The Becks demonstrated their good hearts once again, and brought both of the children into the bunker. In total there were 18 people in the bunker, including children and adults.

[Page 424]