|

|

[Page 236]

By Yaakov Ne'eman (Neumark)

The single Dror training unit in Miktaliczyn in the Carpathian mountains began in the area of the sawmill. More than once, the non-Jews who worked in the sawmill fell upon the members of the unit and beat them. The police and the Jewish owners of the business were neutral.

One night while the guards were changing, two rows of workers waited, armed with staves, and they struck our members who were leaving work. This highlighted the issue, and what we saw in this was the manual laborers trying to get rid of us by whatever means. I publicized this In the Befreiung-Arbeiter Stimme so that all of the movement's followers could help us find a new place to do our training.

September 1931

We received a response from Zolkiew. Shimshon Lifschitz, one of the owners and managers of the glass factory, proposed places for work in the factory, which at the time, received many orders from outside the country. We were informed about this by Aryeh Acker.

Shabbat, October 17, 1931

On a cold autumn late night hour we were on the train of the Kibbutz HeHalutz, with seventeen male and female members. We sat on our bundles and no one came to receive us. Like guests without invitations, we barged into a town with no means at our disposal. Everyone was trembling from the cold. The dog, Luke, who came with us to find work, was at ease on the bundles and suitcases.

With the arrival of dawn, we became aware of the place in which we had stopped to rest, winding around, and going up the mountain of the Re'i.

January 1932

Additional members were added and our group numbered thirty-six people. There were businesses in the city: an oil factory, needle trades, and sellers of household goods. The Halutz center in Lvov had not yet agreed to support our unit in Zolkiew, and attempted to send its own units for training.

After this, the work in the glass factory was limited because of the difficult state of the winter on the mountain. We were in a summer residence, alone, without road transportation, and the financial situation was getting worse. We were burdened with hunger. I recall one morning a few members approached the lair of our loyal dog, Luke, and gathered up a few pieces of bread, no longer considered desirable for humans to eat, that had been thrown to it the previous day.

February 1932

The distress, and the absence of any imminent possibility to make aliyah to the Land, created unrest among the members. This led to stormy conversations, and also to the abandonment of training by several from the heads.

[Page 237]

April 1932

Our training unit was no longer the solitary one of our movement in Galicia. Training units were started in Mosty-Wielki, Lvov, Kharkov, Novo-Suncz, Misziniec, Wieliczka, Milic and Khazhnow.

Activists from Zolkiew traveled the full expanse of Galicia in order to establish training units, and to establish sections of Freiheit, and HeHalutz Ha Tza'ir.

The direction of the HeHalutz movement in Galicia was crystallized in Zolkiew through many meetings and a number of rulings.

April 16, 1933

It was evening. A troublesome downpour of rain that seemed endless came down upon us. We plod and went up on areas with roads and areas with no roads, to the meeting place of the unit. We passed through the neighborhood of the workers in the glass factory, between houses looking like they were ready to topple. We saw hints of the lights from the unit hall in the distance.

The people with the training unit from Lvov reached us, and most of those eligible to make aliyah to The Land from the other training units.

We sat around the table with the trainers to have a frank discussion, deep into the late night. We wanted to speak about our chances to make aliyah, to plant seeds in The Land. We wanted to deepen our training and partnership, and to establish savings accounts for all of the training units. We wanted to study the Hebrew language more intensively, and express our commitment to HeHalutz in Galicia.

In this way, the birth pangs of this new movement in Galicia transpired. The worries about growth and reaching out began, without the leadership of our movement.

By A. Sh. Juris[1]

| Go to the Land of Israel not in order to demonstrate heroism, not to bring sacrifices – only to work |

| (Y. Kh. Brenner) |

I think these are the words of Berger. But there is no doubt that this sentence is etched on the walls of the house of the training point of Dror. The rain messed up the road to reach it. Our visit to the unit in the darkness of the night took place just at dawn. There was an upward winding road to reach the place with very narrow paths in a forest of thick trees. This area is understood to be the source of the legend which began in Zolkiew. When King Sobieski reached the top of the mountain after a difficult battle he called out: ‘Ho! Re'i!’ which means, Garden of Eden. In an ancient place such as this, in the thickness of the forest, rich with plant growth and pools, one could find much in the way of satisfaction and repose, and even be a place fit for a king.

Among the trees is a village yard. The organization occupies two rooms, adjacent to the kitchen.

A permanent group with browned faces and black sidelocks received me initially in a childish manner. There was training going on in the kitchen. Those who got up did so to prepare the modest meal consisting of a mug of coffee and a slice of bread. The boys slept in one room, and the girls in the second. The girls were the first to hear the sound of my footsteps, and opened their eyes which had still been tied up in a dream. Chaste Jewish girls put on their dresses to reach above their throats. For a minute, I had forgotten that my business here was with Halutzot who were training for a life of work. In the eyes of these Jewish princesses, the leader of the girls was delicate, pale-faced and with pretty eyes. Gittl had changed into a nymph of the forest, so, and so, etc. They were in awe. How was it than a man of the organization would look at them in that way, speak that way, use romantic language that was so backsliding.

Wooden beds were assigned to the youth. In the homes of the nobility one can find beds of gold fit for kings and rulers. Here the only ones sleeping were Rachel'lakh, Leah'lakh, Gittl'lakh and Chana'lakh, deep in a treasure store of dreams of good fortune and a new life. The same was true in the second room where the boys, still almost children, were sleeping. These two groups were my sisters and brothers, my own flesh and blood, sleeping two to a bed, Rubenesque, like fierce snakes stretching out their delicate limbs, tired from work. One by one, they opened their eyes, the eyes of innocent children. I scanned the walls until they all woke up. One member drew pictures like Brenner, Marx, LaSalle. There was also a pale picture of the violin of the Land of Israel, Rachel, the handiwork of the same artist, and a message was inscribed: ‘We are for work,

[Page 239]

peace and protection.’ It seemed to me that without martyrs these issues would not be settled. It is the power of Satan that holds sway over those souls not oriented towards peace in our wretched land. It will be necessary to reveal reinforcements like the Hasmoneans. Here on the wall is a picture of the dreaming Halutz. Rise up! Is this not the dream of tens of thousands of Jews who beg to return to their beloved Homeland?

And above all the others was a peculiar drawing of the sky and the earth with a ship at the shoreline, sitting in a dry space. Is this a dream? Is this real, some sort of backsliding or a fantasy? Maybe a symbol and a mystery? And why not? Is this some sort of magical ship that lost its way and got stuck in the heart of a mountain range? Perhaps a small group of two dozen, tender and Jewish souls, burst out of the world and its entirety, and hid here to be alone and to unite with nature and its Creator, with the sky and the earth. A group of people from Robinson Crusoe who stuck a stake in the ground in order to start a new life? With their strong will, and by the sweat of their brow and strong heartbeats, they finished building here, and created a new image of liberated and sincere Jewish-human life. These thoughts disconnected abruptly in my mind, when, in the distance, I saw the boys and girls as they washed their hands in the foothills of the mountain. It looked to me as if with their washing, they were casting off the Diaspora, the bitterness and the wrongs. And like young eagles, they swooped down into the valley to the boiling work in the glass factory. And how odd was this? Brenner once lived in these rooms! The elderly gentile woman still remembered him, and raised his memory eagerly, in a good way, after plowing and working. Now young Jewish people have arrived, and are eager to use the plow. But their path to the use of the plow is not easy, and the ground is hard and alien to them. So what did they do? They constructed a workhouse for tapestries. Delicate soft hands of girls and boys, almost children, weave colorful proletarian stretches of material.

How can I separate them without the gift of Gobelin[2]? There was a small Kilim,[3] which was a precious amulet for me, a precious jewel from the oasis in my birthplace, like a song that was sung by delicate strings of the soul. The songs and dreams were called and soaked and woven among those lovely and precious threads, worth more than gold.

That is how we skip, leap and descend from that sanctified mountain to the muddy valley and the Tension, one of the largest glass factories in the land. The factory exports glasses, cups, lanterns, candelabras and other glass goods, which reach as far as Iraq, Egypt, and the Land

[Page 240]

of Israel. Young boys and girls, tender and delicate, my brothers and sisters, scions of my people, stand beside the fire and exhale, blow, and polish various items of glassware. Glass is hard, but easily cracks and breaks, and it must be treated carefully. I could not contain my feelings and I spoke to one of the overseers of the work. ‘It is worth remembering and to understand, that these workers also have bodies made of delicate glass, and one should oversee them with care.’ These delicate souls dream softly and delicately with longing. These tapestry makers and those who produce melted glass are nothing more than a corridor to a long and hard journey in times filled with much suffering and agony.

It is time for me to raise the candelabra of light that I have, in the dusk of a Tel-Aviv evening. I will look at the marble of the lit candelabra, and I will see the inflamed faces of young men and women beside the glass furnaces, and the boys and girls that were in Robinson Crusoe's ship in the heart of the mountain called HaRe'i. A prayer will then pour out from my heart: Make aliyah! Oy, how I will enjoy seeing you soon and hurriedly washing and purifying at the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, at the edge of the Kinneret Sea.

Oy, Make Aliyah!

Translator's footnotes

By Pinchas Gils

In 1929, when there was unrest in the Land of Israel, Zionist-Revisionist organizations were founded in Zolkiew: A) BETA”R, B) Brit Tzaha”R, C) Nordia. Among the founders were: Mendl Metzger, Moshe Leiner, and Avraham Kanchuger, and these men were the ones who stood at the actions taken by the movement.

BETA”R was an important youth institution in the city, carrying out widely-branched cultural activities, and providing help to the young orthodox members of the Belz Kloyz. A severe depression spread through the young men of the Kloyz at that time. Several of them came to recognize that the time had come to leave the cocoon of the kloyz and to choose a new direction for themselves. They saw the need to renew their lives in a Jewish state, in the Land of Israel, following the concepts of Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Some began to secretly work with the revisionist institution so that their parents would remain unaware of this activity. There were some members who bravely made public their membership in BETA”R.

[Page 241]

|

|

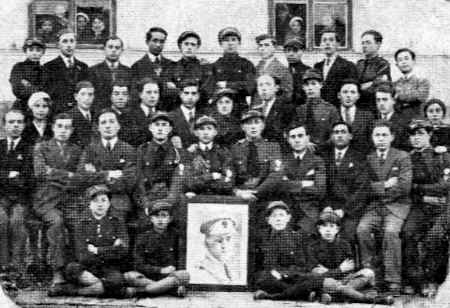

| The Zolkiew BETA”R Branch – 1932 |

The BETA”R members participated in courses to learn how to use arms. They understood the requirement for self-defense when they would make aliyah to the Land of Israel where Arabs attacked Jewish settlements. To our great sorrow, only very few were privileged to make aliyah to The Land because of the dearth of permissions to make aliyah that were given to BETA”R.

Nordia was a group for sports, and organized a variety of sporting activities especially competitions in soccer with other sport groups in the city. The pleasant dreams vanished, and everything went up in the flames of the murdering Germans.

|

|

Chaim Steiger, Joel Reichman, Pinchas Fukard, Asher Kessler, Shmuel Ziegler, Shmuel Fisz |

[Page 242]

By Batya Felsenstein (Zimeles)

A BETA”R branch was founded in Zolkiew in 1929. It was very modest at the start with only a few members attending the branch meetings. An emissary from the head leadership would periodically come and energize the membership to undertake activities and to broaden the branch.

Over time the branch did grow. My friend, Sabina Greidinger, and I, joined and became members, encouraged by Adela Schultz. When we first visited the branch it was housed in the home of Flafler (Dom Zajezdny). Among the leaders at the time were Metzger, Szpritzer, and Feder, who were students in the middle school. The rest of the members were Gils, Babad, Kanczuker, and Shlomo Lieberman, all young men from religiously observant homes. These young men were drawn to BETA”R as a Zionist youth movement that had a positive relationship with the faith, observing the Sabbath and the holidays. The branch was divided into sections with each section having a male or female director drawn from the branch leadership. The agenda of the branch was to lead discussions once or twice a week on a variety of subjects.

There was a strange occurrence once during a discussion with the leader Mendl Metzger as he spoke about the agrarian issues of the Polish farmers. This subject did not align with the ideology of BETA”R and so we investigated this man and what he did. We found communist books in the library that were alien to our spirit. Within days, Metzger was arrested by the police for being a communist. In his place came Kanczuker. The branch continued to develop and we spent many pleasant hours there. The core of our learning was about The Land and ethnic songs and dances of the people. The officers tried to instill in us a love for The Homeland and all our dreams were to make aliyah to The Land.

From time to time members of the HaGalil center in Lvov, including Dr. Uks, Yehuda Orenstein, Dr. Duner, Fishl Sztendig, and Dr. Von-Wiesel visited us to help direct the branch. We visited the small branches in the area with them.

Dr. Duner dedicated much of his time and effort to the Zolkiew vicinity. I traveled to Tartakov on behalf of BETA”R for pre-military training. The training was organized by the Center and every branch was permitted to send a number of representatives. The commander of the camp was Magister Boyko. I went to the division in Kolomyya and from there I was privileged to make aliyah to The Land, where I received news of the permanent development of the Zolkiew branch. During the period of the Holocaust our members stood heroically to fulfill the objectives that were assigned to them.

|

|

[Page 243]

By Meir Melman

Zolkiew, the city to which I am addicted, was where I spent my youth. I am enveloped by emotions and memories, forever etched into my heart, yet I will not return to Zolkiew. I will not find any person there, as they were all eradicated from the face of the earth. Everything that comprised the body and spirit of those times has changed. Even the name has been changed. The city is no longer called Zolkiew, but Nastorov.

Zolkiew is a city from which some of the Great men of Jewry arose, whose lights were followed by many. It was the city in which the first printing houses of Poland were founded. It is a city that was outstanding in its natural beauty and in its Renaissance architecture. Yet it was also a city of strife between Poles and Ukrainians, and Hasidim and Mitnagdim. A unique expression to describe Zolkiew, was that it had its own face.

I found destruction when I made my last trip to Poland in 1945. Even the cemetery had been destroyed and its headstones smashed. Our city drank from the cup of Hemlock until its end, like all the other cities of Poland during the Holocaust.

This undertaking is worthwhile in order for our children to know what their fathers did, to recognize one corner of our cultural lives in Zolkiew.

|

|

Standing (left to right): Baruch Siddur, Yitzhak Lichter, Malka Schweitzer, Zvi Lauterfacht, Git'cheh Reitzfeld Bottom: The Prompter (Sufler) Meir Katz |

[Page 244]

The Drama Club was founded in Zolkiew after the First World War, in 1919. This club influenced us considerably. It offered culture and friendship in our lives in the city during the period between the two world wars. At this time, a drama movement of this sort began in all of Galicia and a drama club could be found in most cities. However, it is possible to establish without modesty, and for the sake of truth, that the Drama Club in our city was one of the best and most productive in this part of the land. And I, whose entire life is dedicated to the theater, selected this area, in which I saw my mission and destiny, and I worked hard to carry it out.

While I was still attending the gymnasium, I was drawn to presentations and acting. After the completion of studies and final graduation tests, we gathered in the Engelsburg pub (Weinschtock) and decided to put on plays. I was privileged to be made the leader of this group which included: the Altman brothers, the Tencer brothers, Basekhess, M. Ungar and even a few adults, among them Sender Lifschitz and Leib Hirschhorn. We began to work.

The first play we put on was The Jewish King Lear by Yaakov Gordin. According to my memory, Gisela Bendel, Hella Apfelschnitt, Mashka Bindel, Avraham Schwartz, Avraham Basekhess, Sim'ka Tirk, Mendl Altman, and I, participated in this first production, and I remember well, the impression that we made. A unique hand-made stage was erected in the Bendl family dance hall in the market, which is where we performed. The reaction was so favorable, and people in the city were so excited, that we had to present the play two times. The men, women and children ran to see it and watch the actors. I was 19 years old then, and I played the part of a very old man. The appointments on stage were very modest. The makeup was in the hands of Freiman the barber, and this was the first time he performed this kind of work. We didn't have props, and the conditions were not the best for the performance. Yet, despite this we were received very favorably.

The ardor of the young actors and the happiness of the city folk created an atmosphere of admiration for our club. Right after our presentation of The Jewish King Lear we prepared a second play, The Father, by Strindberg. The text was translated especially for us by Reuben Tzimerman. In addition to all of the actors in the first play, Bran'ka Schlosser joined us. She was a delicate figure who possessed a deep understanding of theater and acting. She was also one of the supporting pillars of our Club. Her talent was apparent in the role of Leah in The Dybbuk.

[Page 245]

The Drama Club was a basis for the establishment of the culture club, the Kultur-Verein, in our city. The founders of the club were Dr. Reuben Tzimerman, one of the important people in the Bet HaMedrash who transitioned to European culture, Moshe Michal Ratt and others. They attempted to develop the Club and succeeded in drawing interested people from all parts of the city. At the time when the Hasidim attacked the actors in neighboring towns, they were nicknamed Teutons (kamedinatschkeit), but our city exhibited patience and understanding toward the Club to a great extent. In the neighboring towns, the religiously committed nicknamed the actors as apikorsim, leading the city off the straight and true path, but in our city the Haredim and those that prayed in a shtibl stayed silent. In time, a separate hall was constructed in the orphanage, as a result of the efforts of the engineer Lichtenberg, and Shimshon Lifschitz, and the hall was reserved for the Club and its activities.

The Drama Club went from success to success after its first presentations, and it continued on to present other plays: The Miser, The Slaughter, Motkeh Ganev, The Village Youth (Der Dorfsjung), The Baleboss from Vilna, The Fields and the Vegetables, Days and Nights, Absorbing a Slap in the Face, The Revisor, The Flood, The Mute, and others. In addition to the actors I already mentioned, other participants in the plays were: Yehoshua Indyk, Git'cheh Reitzfeld, Olga Lichter, Fried'ka Fish, Giza Landau, and Herman Armon, who specialized in decorating for the Club.

To the credit of the Club, let it be said that in the selection of the Rapporteur, the literary content of the play and its cultural character was always included. Accordingly, much credit goes to the Club in the creation of the Kultur-Verein. It was an organization that transcended party affiliation. It was an institution for the dissemination of general culture and Hebrew in our city.

I have not recorded the names of everyone who participated in the Club as ardent supporters. However most of them were exterminated by the murderers, during the rule of Hitler, ימ”ש.

Yet, here are some memories of a few of them. Avraham Baskhess came from the enlightened youth of the Hasidim, who, even before the First World War, unyoked himself from the burden of mitzvot, and he emigrated to Argentina in the 1920's. Mendl Altman, a very capable commoner, moved to Lvov after he was married and cut his ties to the Club.

The following individuals from the intelligentsia participated: Dr. Hertz Gleich, Runek Wachs, Mish'keh Bindel, and Dr. Schlusser, who saw the Club as an affection-creating activity.

[Page 246]

My brother, Michal Melman excelled in his performances and became endeared to the audience. He had much energy and knew how to imitate different types of characters. My brother lived in Israel.

Gusta[1] Dampf added grace to the stage with her pleasant appearance. Simka Tirk, Ida Feier, and Ethel Orlander memorized the lines of the parts of the plays, and it was impossible to leave them out of the performing cast.

Leibik Patrontacz earned the affection of the audience for his straightforward approach in his acting. There were many that were as good or better than these people. As they say in the theater: ‘they poisoned the air of the theater, and the poison penetrated not only the hearts of the actors, but also the hearts of the helpers.’ Shimshon Lifschitz demonstrated a great deal of energy and was a generous community activist. There were also the engineers, Wolf Lichtenberg, Anshel Sobol, and Moshe Acker, who worked to assure that their friends would be rewarded with fame as actors. They were satisfied that Zolkiew's drama club rose to grandeur.

There were more participants drawn from the youth of Zolkiew in the last years before the war. Among them were Malka Schweitzer, Rivka Lida, Fried'ka Fish, Olga Lichter, Baruch Siddur, and others, to my chagrin, whose names I do not remember.

The Club itself would not have succeeded in fulfilling its goals were it not for those who tended to the technical resources and the air of comradeship of cooperative endeavor. The engineer, Lichtenberg, Shimshon Lifschitz, and Yehoshua Czaczkes, planned and oversaw the building of our hall at the orphanage. Lifschitz and Lichtenberg did a great deal to expand the Club which eventually was transformed into the Kultur-Verein, an organization that transcended partisanship and was affectionately regarded by all the Jews in the city. The club continued to grow and remain active, until the Second World War, after I left to study and committed myself to the theater as a profession. It is possible that the activities of the Group shrunk, but its cultural work and support for the city remained in its view. Dr. Reuben Tzimerman, contributed a great deal to the cultural activity, especially at the start, and was perhaps the last one of those on the benches of the Bet HaMedrash that went over to the activity of European culture.

The Drama Club, founded in 1919 in Zolkiew, influenced the rise of other clubs. It energized the labor units, Poalei Zion on the left and right, to create their own clubs. These clubs were weak, but still active, as they took in both young and older people to appear in their cultural presentations. One such individual was Moshe Rucker of the Leftist Poalei Zion, who committed himself to this work and various community undertakings, for many years.

I briefly recollected here some of the cultural work in Zolkiew during the decade of the 1920s between the two world wars. This was the epilogue of three hundred years of Jewish Zolkiew that was exterminated in Sanctification of the People. Let our children, who are educated in other subjects and political areas, understand the cultures, and the variety of friendship we experienced in the years of our youth. Our lives were filled with substantial content. Our children feel that they are a continuation of those who came before them.

|

|

put on by the Zolkiew Drama Group in the Year 1935 |

Translator's footnote

By Henya Graubart (Zinger)

Undoubtedly there will be much written about prominent people, Torah Sages and Great Men of culture in our city, and about their various initiatives. There is a need in my soul that makes me feel that I must record the activities of a group of modest ladies and the greatness of their good deeds for the poor and the needy in our city.

A group of women founded a society that was called Bikur Kholim v'Hakhnosas Orkhim. The activity of this group was based on the core principle of Matan BaSeyser in their oversight and support of the needy in our city. The ladies of this society did not wait for the needy to come to them and ask for help. These women went and found those individuals in need of concrete and spiritual support and who may have been embarrassed to reveal themselves and their poverty for everyone to see. The help was provided secretly, and every day, the society fulfilled the noble and traditional mitzvah of ‘all who sustain [even] one Jewish life.’

Mrs. Leitza Jules headed this group, and was known as Leitza bat Petakhya. She was a short woman, with a large head. She covered her head with a wig larger than the size of her head, which only reinforced the impression of a big head relative to the size of the rest of her small body. She exhibited an unusual amount of energy and strong organizational skills. Based on these attributes, she miraculously and successfully implemented lofty deeds. She founded this philanthropic-volunteer group and was its living spirit. She made use of a staff of women who formed a nucleus for the charitable undertakings. These women were Tuvi'cheh Sobol, Sarah Orlander, Feiga Bodek-Sobol, Esther Rachel Mansz, Sarah Rachel Rad, Sarah Lifschitz, ladies of the Khari family, and my mother Miriam Zinger, all of whom were exterminated in the Holocaust.

These active women frequently met at our house. As I was present among them, I was familiar with their work. Leitza Jules always had a list of needy pregnant women in her hand, and for each of them, she prepared a gift bundle consisting of two bed sheets, diapers, infant clothing, baked goods, candies, and a sum of money. The help did not end with this. There was a scheduled follow-up after the mother gave birth, and if she needed additional help, whether substantive or spiritual, additional help was provided. The women also organized visits to the chronically ill, and covered some of the nights, something that added encouragement to the patient, and greatly eased the burden of the exhausted family. Financial help was also provided for those in need, for the purchase of medicine and other items, as needed.

The ladies undertook a special project for Jewish patients in the government controlled hospital. There was a government hospital that was partnered with the cities of Rawa-Ruska, our city, Kulikovo, Mosty' Wielki and the entire surrounding area with tens of such large villages. Most of the patients were Christian as well as the physicians, the nurses and all the hospital employees. You can imagine the emotional state of a Jewish patient, usually with a beard and sidelocks, who had been tossed into this unfamiliar place, in bed, and subject to some hostility. Families of patients from Zolkiew were able to bring kosher food to their sick patients, and also relieve their loneliness. But for sick patients whose families lived 40 km. away from Zolkiew, the issue of the loneliness of the patients and the kashrut of their food was a matter of sustaining life. The lady, Leitza bat Petakhya, rose to the need and created a kosher kitchen. She received permission from the management of the hospital, and they served three, tasty, kosher, meals each day, to every sick Jewish person who lay in this hospital. To make this work, they hired a cook, and volunteer women helped, according to a regimen, to divide up the food on a daily basis among the sick in the various sections of the hospital. I would go together with Dora Orlander, on Mondays and Thursdays, to serve the food in place of our mothers.

[Page 248]

There was a restored house not far from the hospital, with four rooms, three of which served as bedrooms for poor visiting guests who were previously compelled to sleep on a bench or the floor of a synagogue or yard. The fourth room served as a kitchen for the hospital patients. The poor were permitted to lodge for two nights at no cost. It is easy to ask, what is the meaning of lodging for two nights at no cost, but even this elicited thanks for the effort of this same blessed woman.

Leitza, did not forget that there were also people in need of loans for a variety of purposes, and she set up a small charity box, and distributed loans to the needy, with low repayments and no interest.

It was understood that all the activities were tied to recognized monetary outlays. But no woman like Leitza bat Petakhya, would get upset over financial difficulties. She found her own means of accessing financial resources. She collected set donations, which on a monthly basis paid fixed amounts to the ‘box,’ under the eyes of the special Shammes who acted as the collector. She collected donations made during weddings, parties and joyous occasions. She organized a sort of Purim Carnival for the purpose of collecting money. She put up likenesses like Ahasuerus, Mordechai and Haman, mounted outside of the city on beautifully decorated horses, provided all manner of masks, and the Purim Spiel for the enjoyment of both the children and adults.

All of this work was managed until the outbreak of the Second World War, but even during the rule of the Soviets from 1939-1941, the activities of this group did not stop. They applied their work to an additional sphere, since, as a result of the war, there were tens of thousands of refugees who fled from the areas conquered by the Nazis. As a result, several hundred Jewish refugees found rescue in our city. The refugees were largely without resources, and it was necessary to provide them with a roof over their heads and other first-aid needs. Kitchens were organized, clothing was divided up, and they looked after providing lodging in homes of ordinary people. When this first period of the war began, there were still synagogues and Houses of Study. These refugees were not forgotten even after they were exiled to Siberia. Packages of food and clothing were sent to them as well as matzo for the Passover holiday. And all of these undertakings were done under the guidance and vitality of Leitza. I was able to see, almost to the last minute of her life, during the capture of the city by the Germans, that she did not stop her work providing sustenance to the needy. With dedication, she gathered food in the ghetto from those who had food, and divided it among the downtrodden, until together, with all the martyrs that were exterminated in the Holocaust, the bitter fate overtook her.

By Tova Altschuler (Eikhl)

There was an elementary school in our city run by nuns. This vision of this institution is etched deeply into my memory to the extent that I can still picture everything that took place inside each room, and each corner, as if I had just visited it the day before yesterday.

|

|

There were two elementary schools in Zolkiew. One was managed by the town and the second, in which I studied, was a girls' school run by nuns. It was a two-storey white building with spacious rooms inside. A well-tended garden surrounded the house. A marvelous cleanliness prevailed around the entire institution and its surroundings.

A special air of attention, diligence, order and cleanliness prevailed, due to the special appearance of the nuns, and the wondrous and distinct aroma that emanated from the walls of the institution that covered you with a measured amount of fear and respect for dignity.

[Page 250]

I spent my first day in school in fear, hiding underneath the bench. I was in awe of the nuns in their long brown dresses, their light-brown aprons, and the white-starched head coverings. Every outfit they wore had a large crucifix covering their middle. In time, I got used to them. The nuns were good teachers, and they maintained order in the class, from discipline to anti-Semitism.

It was not just once that we heard the expression, ‘dirty Jewess,’ from a nun, but when it came to subject matter, they were objective. When Jewish students excelled in their studies, their report cards were truthful reports of their work. When the Christian girls recited their morning prayers, and it became their turn to pass by the statue of the Holy Mother, they lowered their heads and interlaced their fingers. We, the Jewish students, were ordered to rise and stand in silence for the entire time of the prayer. We were eight Jews among 30 Christian girls, and we felt a little separated. During recesses, it was our custom to eat our meal in a grove of trees that was adjacent to the school. The Christian girls sat apart from us at a distance, and we were alone without companionship. We did not take part in the drama plays of the class. It was enough for us to be written up with a small mark, and we immediately earned the rubric of Żhid.

Classes at this school were also held on the Sabbath, but the Jewish girls didn't come on Sabbath days. Sundays were a general holiday and so we enjoyed being off from school for two days a week. At every turn, anti-Semitism grew stronger. When Poland became free in 1918, international pride was uplifted, and we organized our HaShomer HaTza;ir group. We were all proud to belong to this organization. It was our first stage for the awakening of an international Jewish Zionism that in the end, brought us to the Land of Israel.

By Tzilina Koninsky (Lisfeller)

The Jewish Orphanage in Zolkiew on ul. Lvovska was one of the most important community institutions in the city. It was established in 1920, and dedicated to the gathering of orphaned, or half-orphaned children, whose parents died or were killed during the war years. The following members participated in the committee that founded the orphanage: Ignatz Fish, Isidore Czaczkes, Bernard Kesler, Fundik Yelman, and Hecht. Fish, the advisor, headed the committee. The orphanage was called, The Orphanage for Ignatz and Rosa Fish. The committee purchased a pleasant villa which was customized to fit the needs of the institution, such as wide bedrooms, a dining room, a gathering hall, rooms for the teachers, a kitchen, etc. There were buildings in the green, grass-covered yard, for the management offices and the home of the Director.

[Page 251]

Sixty boys and girls were taken in by the orphanage. Most of them were full orphans, having lost both of their parents. Very few of the children there had only one parent. The children were mostly neglected, undernourished and frightened. It was difficult for them to adjust to their new surroundings, the discipline of the institution, sanitation, etc. Nevertheless, after a short time as residents, they were happy and became one large family.

The first governess was Mrs. Rein from Lvov. She was experienced in this endeavor. The teacher was Stefania Maimon, the supervisor of the farm area was Rivka Deutscher, and the Janowsky family took care of support requirements. The children also helped out on the farm, the garden, caring for younger children, and repairing bricks, etc.

All of the children attended an elementary school, and after they finished studying there, the girls went to a craft school, a branch of Mrs. Klaftin's school in Lvov, in which they learned to weave and sew. The boys learned trades from working men, as apprentices, and some studied at the gymnasium. The oversight of the committee and its members resulted in good economic conditions and good attention to the health and education of the children. This created a favorable atmosphere for the happiness of the children and a place for them to develop skills, form friendships, and forget the bitter fate of being an orphan in this group.

The children were educated in the spirit of Jewish tradition, and observed every holiday. They organized the Seder for Passover, to which the members of the committee and guests were invited. They arranged walking expeditions, and their plays became cultural events in the city. Zibert taught dance, Mrs. Apfel and Fundik took on roles in the plays. The revenue from the plays were dedicated to help the children in the institution and further their education.

After some years, the management changed, and Stefania Maimon was appointed as the Governess. She was a single woman who committed her life to the institution. In 1936, the budgetary support from outside of the country ended. Control of the orphanage was completely in the hands of the Jewish community, and it had to rely on donations gathered by the ladies and friends of the orphanage. The economic status of the institution deteriorated significantly. Many of those educated there grew up, entered a profession and found it possible to leave the orphanage, but its severe economic condition did not improve. To make matters worse, the committee that had worked for so many years with commitment during the initial years of the institution, disbanded because of disputes among its members. Only a few of the members of the committee remained on their job till the end, and they were Keller, Mrs. Hecht and others.

[Page 252]

The entire load of difficult problems fell onto the Governess, Ms. Stefania Maimon, who braced herself to take a stand with much energy and commitment. Because of the difficult financial times, she was forced to let all of the employees go, and single-handedly, managed all of the farm work. Only the children helped her in this task.

|

|

|||

In the end, it was not possible for her to cover her own expenses, but she did not leave her post. She sold her jewelry and her piano, which constituted all of her assets, in order to secure sustenance for the children. She helped many students finish their courses of study under these difficult circumstances, and to leave the institution as people of standing and worth, able to live independently, and raise families. They were tied with bonds of loyalty to their Mother-Governess.

This heroine was a modest and quiet figure, a teacher, a mother to orphans, and attached eternally in the memory of those few that remained alive after the terrifying war. They will not forget her good-heartedness, and wondrous level of commitment to them.

Let these few lines be a memorial to Stefania Maimon with admiration.

By Batya Felsenstein (Zimeles)

There were many children in Zolkiew who were orphaned after the First World War, and without parents, were left with no means of sustenance. With the help of The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, known as The Joint, a new institution, The Orphanage, was created for the ingathering of war orphans. The house served not only as a place of refuge for orphans, but also a site for general culture. Various people were invited by a variety of youth organizations to make speeches. As there was a large auditorium in the building, it also served as a place for theater productions. The admired and enchanting actors came from outside the city and were directed by, among others, the talented actor, Meir Melman.

The living spirit of the orphanage apart from the management, were the two Maimon sisters. The older sister was the pedagogical teacher of the institution, and the younger took care of the needs of the household.

After some years passed, when the children of the institute finished their studies in the elementary schools, the question arose. What now? How was it possible to send the youth out into the world without a craft?

|

|

Dr. Klaftin is in the third row, sixth from the left. |

The boys were able to find workable options, but not the girls. After doubts and much rule setting, and with the advice of the remarkable woman, Ms. Klaftin, the principal of the trade school for girls in Lvov, it was decided to create a trade school in Zolkiew. Ms. Klaftin understood that girls needed skills, especially for those women who remained alone in life, and she came to rescue us with her help. She strengthened the trade school in our city, the only one in our vicinity other than Lvov.

[Page 254]

The opening of the school made a powerful impression on me. The school leadership and all the girls from the orphanage gathered together in the large auditorium of the school. Young women who had graduated from the elementary schools and who were considering making aliyah to Israel, saw that learning a trade was the right and proper thing to do in order to be able to earn a living from their own manual labor.

The day following the opening of the school, organized study began in the large auditorium where there were a number of sewing machines, gifts from American Jews. Alongside each machine sat Jewish girls being taught by Jewish teachers. There were also teachers who were trained at the trade school in Lvov, founded by Ms. Klaftin, for weaving, cutting and sewing, teaching in our new institution.

The girls studied theory in the afternoons, which included subjects such as the Hebrew language, mathematics, Jewish history, literature, and the lore of secular materials. The work became more difficult over time. The teachers of this material in the institution were very educated. They were students at the University of Lvov, and over time, the institution hired more and more teachers.

The morning hours at the school were unforgettable. The girls learned together in the free atmosphere of the Jewish school. This experience engendered a wonderful feeling. The humming of the machines reminded us that there was already a new life in The Land. We did not even think about the possibility of the Holocaust that was drawing closer.

Girls studied for three years in the school and there were final examinations at the end of the third year. The first part of the final exams consisted of a Polish introduction, taken in part from the government's education requirements, and the results set down the fate of the school. We emerged from these tests with great success, and the overseer permitted the institution to receive full privileges.

|

|

Standing: Nina Tzeimer, Ephraimovitz, Genya Oliphant, Mina Witlin, Chana Berisz |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 Sep 2024 by JH