|

|

[Page 226]

By Meir Lifschitz

|

|

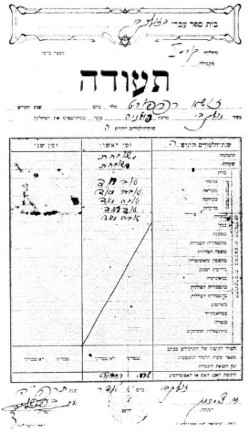

| A report card from the Hebrew School in Zolkiew – 1925 |

The year 1917 was a time of change for the Jews of our city with regard to study in the intermediate and higher level schools. This period also heralded the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the genesis of the first new, democratic states. In that year, many of the Jews in our city attended the government gymnasium. There were two parallel classes in the gymnasium. In the first class, Jewish children made up fifty percent of all the students. They were the sons of merchants, retail storekeepers, and laborers. There were sons who were Maskilim and knowledgeable in Torah from the well-to-do, and also some from ordinary families. All aimed towards attaining the Matura, an academic diploma granted upon graduation. Truthfully, the enlightenment of their sons was not a concern of the fathers. Their desire was to secure the economic position of their sons, and to raise their standard among their peers, as the living say, in an ambience of dignity and economic means.

|

|

Sitting: Avigdor Zager, Mira Zimeles, Rosalia Lichtenberg, Tunka Shtraich, Clara Apfel, Clara Bandel Standing: An entertainment group from Lvov (third from the left: Shammai Zuvl) |

[Page 227]

There were many repercussions as a result of this transformation. It was as if there was an unwritten law, that the intermediate level of learning was especially created for the sons of the populace who spoke Polish, or to the sons of doctors and lawyers. The language they spoke and their position separated them from the general Jewish people of the city. Justifiably or not, they were seen as assimilationists who mimicked the gentiles in their manner. The Polish government gymnasium looked like the transfer of the intermediate level Enlightenment into Jewish ambience. Jewish children spent most of their time in a Heder, grew long or short sidelocks, and followed the traditional customs of the Jewish religion. When the change came along, many of them turned to the gymnasium. They had to cut their sidelocks, change their clothing, and study in school six days a week, including the Sabbath. It was difficult to become accustomed to this new way of life. These students were not fluent in Polish, and their pronunciation was very distorted. This made them the laughingstock of the teachers and students who were not Jewish. Polish pronunciation was difficult for many of them, like the splitting of the Red Sea. The letter ‘s’ came out of their mouths as ‘sh’ – the ‘tz’ as ‘tch’ or the reverse. They learned Polish grammar easily, but not the pronunciation. On the Sabbath, many rushed to the Great Synagogue to pray at the first minyan. They ran back home after services, hid their school materials underneath their jackets, and hurried off to the gymnasium, where another chapter of anguish took place. Should they write on the Sabbath or not? The older students wrote on the Sabbath. The new students who came from a traditional household were fearful and undecided about this issue, and even saw an international quandary in it. Those who decided not to write on the Sabbath, but rather to learn the material by heart, gave a sign to their friends and teachers that they were fighting for their privilege promised to them by the Constitution. Therefore, the professors did not have the right to force them to act otherwise. Their rebellion caused them to ‘spill blood.’ As not all the teachers, among whom there were also anti-Semites, were prepared to consider this explicit writing in the Constitution, they vilified the Jewish students, and pressed them hard, to force them through the gates of enlightenment. In any event, the number of students did shrink over the years. There were very few Jews who succeeded in reaching the eighth grade. There were fewer students and only one class remained out of the two parallel classes. Yet, there was a higher percentage of Jewish students in the class compared to the eighth grades of prior years. The number of academically trained youths in Zolkiew was noticeable.

[Page 228]

Most of the graduates of the gymnasium attended the university. Very few succeeded in infiltrating the faculty of medicine, and many studied law and philosophy. There were not many Jewish students in the polytechnic school. With the passage of time, during the 1930's, tens of young students wandered the streets of Zolkiew, proud of their standing, respected and very acceptable. The female graduates of the Seminary were almost equivalent to them in status.

The young academics in Zolkiew were divided into different groups based on their social status and their ideological tendency or partisan identity. Their feelings of jealousy towards the non-Jews resulted in their attraction to join the Christian youth activities. They did not particularly succeed in this undertaking, however. The Polish youth were not inclined to accept Jews into their group. Because of this, those Jewish youth with personal pride and a sense of international Jewishness, recognized his place among his comrades and worked within the confines of his group. Their practical objectives included mutual help, that is to say, financial assistance through loans to comrades who did not have the means to pay tuition at the university or polytechnic. To support the house of the ‘Rigurisentim’ in Lvov, where the Jewish students of Eastern Galicia lived, including scions of our city, and providing for them to be able to eat at the manse at a low cost. To raise the funds for these purposes, the students organized dance parties, and collected donations from the working intelligentsia and the well-to-do of the city.

Many were praiseworthy in the fact that they did not shirk this responsibility they had assumed years before, even if their own economic situation worsened, they had to fight to keep their clients, and had difficulty earning the minimum income they needed to sustain the members of their household and to strengthen their offices. The young academics enjoyed their friendship with both other youths and the adults, in relation to their expression of the Haskalah, despite the fact that there was a great difference between the new lawyers and their colleagues schooled before the First World War. But those students who grew up on the Jewish street, through which Jewish air breathed in their traditional and international houses, knew how to divide their energies between work within the academic Agudah, and other Zionist organs, such as Hitakhdut HaShomer Hatzair, The Keren HaKayemet committee, and the Kultur Verein groups which adhered to the culture and faith. The Zionist students wielded influence over their assimilationist comrades, such as the families of Miller, Czyckes, Kaczka, and Whitman. With a modicum of Zionist ideology, these families knowingly, or unknowingly, drew nearer to their people. The brothers Moshe and Chaim Katz, Yaakov Gelber, Izia Zayger, Manyk Apfel gave generously of their youthful ardor, and put in a great deal of work into the Kultur Verein.

[Page 229]

|

|

|||

|

|

Standing: Michael Melman, Joseph Giless, Joseph Patrontacz Sitting: ,b>Yehoshua Indyk, Shimshon Lifschitz, Akiva Cohen |

It was recognized that the core of the struggle of the youth was forsaken at a place such as in the intermediate and higher schools. There, they struggled for a place in the economic life and comradeship of the young Polish country which had returned to life after many years of subjugation. This was not the case with the economic conditions of Polish Jewry in the days of the eve of the Second World War.

By Zutra Rapaport

The HaShomer Hatzair movement existed in our city before the 1920s. At that time, the concept of Zionism attracted the souls of the youth of the City and motivated them to prepare for aliyah to The Land. They began to learn the Hebrew language. They even tried their hands at learning tangible work, such as studying the kinds of skills that would be useful to them when they had the privilege to make aliyah to The Land. Among these pursuits were agriculture, carpentry and others. The young people who were most taken with the idea of aliyah were the educated youth. They had decided to shed the yoke of their current life in the Diaspora. It was a generation of Jewish youth whose origins began in the Land of the Patriarchs, in the Land of Israel, who began to see with the eyes of their spirits, how their future lay in the global world.

|

|

|||

[Page 231]

Awareness of reality broke through the strong desire for aliyah. Disappointment could be seen on the faces of those desiring to make aliyah, but who were thwarted by the limitations placed by the Mandate Government. In those days, before the illegal aliyah began, it was possible to reach The Land only by obtaining a ‘certificate.’ The number of certificates provided to those in the Zionist movements which allowed entry to The Land was very limited. Accordingly, it should not cause any wonder that only a few, solitary individuals succeeded to attain their heart's desire. During the years when there was no possibility to make aliyah, the enthusiasm of the youth decreased. They concentrated their efforts in local businesses. They broke off their connection with the organized pioneering movements, established families, and joined various Zionist bodies in the city, such as The Zionist Histadrut, Hitakhdut Poalei Zion, or the division of Poalei Zion on the Left, and Mizrahi. They actively worked within the limitations of the committees of the independent institutions for the Land of Israel, or they engaged in initiatives in the life of the Jewish community in the city.

|

|

Standing (left to right): Israel Deutcher, Manyk Reitzfeld, Avraham Lichter, Jonah Katz |

During the 1930s a new wave arose among the Jewish youth whose objectives were to abandon their old homeland. This occurred in the context of the increase in anti-Semitism and the oppression of the Jews in Poland, at a time when the economic situation continued to worsen, and when the Numerus Clausus decrees constrained the educated Jewish youth from joining the universities in Poland. This became a day-to-day matter. The new wave became visible with the growth of an international movement to make aliyah to The Land, notwithstanding the difficulties involved in such a move. Hundreds and thousands of the young people in Poland announced their will to join the ranks of HeHalutz. However, as only those who had gone through previous training in a training unit were qualified to receive a certificate, there was a renewed incentive to be trained. The HeHalutz central offices in Warsaw and Lvov began to increase their training activities by creating additional training units. Work units sprouted in villages, cities and towns, in accordance with the needs of the location. Training in the villages centered on agricultural work, and in the more urban areas, the training was based on factory work and manufacturing initiatives. These training units had a double objective: to accustom the youth to the kind of manual labor that was not presently common among urban youth, to introduce them to cooperative life, and life in a Kibbutz, within whose boundaries one would have to live when reaching The Land.

|

|

[Page 232]

There were different youth movements organized in the Histadrut of HeHalutz in Poland as part of active units in the Zionist Histadrut. There were two central approaches by the organizations. One was Labor in the Land of Israel, and the other, was that of the General Zionists. The youth movements, Gordonia, Dror, Borokhovia, HaShomer HaTza'ir and others, were part of the Labor approach, and Akiva, and others, the General Zionists. In general, upon reaching The Land, the Halutzim joined the existing Kibbutzim. Members of Gordonia joined Ikhud HaKevutzot. The Dror people and Borokhovia went to Kibbutz HaMeukhad, and the people of HaShomer Hatzair went to Kibbutz HaArtzi. The HaShomer Hatzair movement generally centralized Halutzim making aliyah from Polish training units as the foundation for the creation of a new Kibbutz in The Land. This was due to the fact that the number of members of HaShomer Hatzair in The Land was limited.

|

|

|

|

| (Left to right, sitting): Manyk Reitzfeld, Shoshana Rubin, Joel Hystein, Zelda Fogel, Zutra Rapaport, Batya Katz, Israel Deitcher ,Chana Laufer, Jonah Katz. First Row (Standing): Yitzhak Lichter, Leib Halpern, Hersh Schwartz, Avraham Lichter, Kuba Patrontacz, Avraham Shiltiner, Naphtali Banter, Michael Schuman, Sholom Witlin. Second row (standing): Shmuel Heller, Moshe Ritter, Eli Heller, Joel Stahl, Schraga Shiferling, Chaim Serber, Yaakov Katz Sitting (below): Yitzhak Genauer, Getzl Langer |

|

|

Standing: Bluma Brudinger, Aharon Stein, Shoshana Hirschhorn, Chaim Serber, Freid'keh |

|

|

[Page 233]

This was different from the status of the Kibbutzim in Kibbutz HaMeukhad, which was prepared to take in Halutzim without numerical constraint, a trend that was realized in our time because the Kibbutzim in Kibbutz HaMeukhad were among the largest Kibbutzim in the country.

There were two centers of the HeHalutz Histadrut in Poland. One center was in Warsaw, the capital of Greater Poland, and the second was in Lvov, which included areas that had been formerly Galicia. Those who did not belong to a youth movement could also join HeHalutz branches in the cities of Greater Poland. This was different in Galicia where most of the HeHalutz members were part of HaShomer Hatzair. Potential members who were at an age of twenty-eight years and over, and who may have wanted to join HaShomer Hatzair, could not enter this circumscribed group. In time, the chief leadership of HaShomer Hatzair increased membership among their ranks, by taking in the unaffiliated, from the age of twenty-eight and up, into a separate unit connected as a branch to the head leadership of the movement. This was how the Histadrut of Stam HeHalutz of HaShomer Hatzair was created in Galicia. Also those Kibbutzim that were destined to be created in the Land of Israel were designated as separate Kibbutzim of the Histadrut of Stam HeHalutz, so that they had an association with the Kibbutzim of HaShomer Hatzair, and could be called by the inclusive name of Brit HaKibbutzim in Israel.

In 1930, several members of the Zolkiew branch of HaShomer Hatzair gathered in the presence of the representatives of the head of the Lvov HaShomer Hatzair. After the representatives explained the new movement to us, it was decided, on the spot, to create a branch of Stam HeHalutz in Zolkiew. An organized committee was elected, of which I also was a member. In a short period of time, tens of the youth in the city joined us. They came from all ranks of the people: educated youth, the youth of B'Nai Tovim, and from simple households, most of whom worked in the fur trade, one of the common trades in our city. At first, we rented a separate hall in the Zubl Tower in order to enable the members to get together. Afterwards, we moved to a larger hall on ul. Niovitowska, in the neighborhood of the elementary school. After a year, we rented a house with two rooms, in partnership with the branch of HaShomer Hatzair, in the familiar Acker family house on ul. Lvovska. The membership was divided by age, and they were involved in broad organic and cultural activity in partnership with the members of HaShomer Hatzair. Representatives of the central Stam-HeHalutz from Lvov visited us frequently, to present their teachings to the city branches. We were also reached by lecturers who were sent by the leadership of HaShomer Hatzair.

One of the important initiatives was the creation of a Hebrew library and evening classes for learning the Hebrew language. Tours of different Kibbutzim were arranged or in partnership with all of the members of the movement. The members attended general assemblies on Sabbaths and Festival Holidays. These meetings were often held outdoors, under open skies, during which discussions took place on matters about the Land of Israel. There were also pleasant events with singing and dancing of the Horah. The members of the Stam HeHalutz branch in Zolkiew applied themselves to all of the Zionist activities that took place in the city, and actively participated in the committee for Keren HaKayemet. They even helped to collect donations made to the ‘blue boxes’ of the KK”L that had been distributed throughout the city. They also collected donations for the Ezra institution, whose goal was to financially support the Halutzim of Zolkiew who could not afford to pay the expenses of making aliyah to The Land. Our contributions were more than respectable, and as understood, we took an active part in the elections to the Zionist Congress.

[Page 234]

We found a new activity in our lives with this work that meant so much to us; it provided us with a purpose in life that was previously invisible to us. We felt that in the end that we had begun a new path in our lives. And even though that path was filled with traps and bumps, it nevertheless was the thing that would eventually bring us to the fulfillment of, and give substance to that which we deeply cherished. Life became more interesting; it aroused passion and zeal. We followed with interest what was being done in the Land of our Dreams, and every item of news from The Land was received with joy and a lifting of spirits. The dream of all of our members was to accelerate the end to our old way of life in the Diaspora, and to open a new page, a new life, and to be counted among the committed builders of The Land.

At the same time, the central Histadrut of Stam-HeHalutz in Lvov established three groups to make aliyah from the branches of the movement in Galicia, and created special training groups for them. The three groups divided by age were Avodah, HaMefaleys and Amal. Whoever wanted to join any one of these groups was required to enter training work in one of the units of the Kibbutzim. These training units were set up in Lvov proper, in Nadvirna beside Kharkov, and in Bruzhniow beside Stanislaw and in various villages, in which most of the work was agricultural. The center of the training work was in Bruzhniow, which was surrounded by forests on all sides, and the Halutzim worked there, all hours of the day, cutting down trees and sawing them in the large sawmill. There were three units of training In Bruzhniow. These units were Stam HeHalutz, HaShomer Hatzair, and HeHalutz Akademi (H.A.Z.). From one period of time to the next, there were meetings arranged by the Kibbutzim of Avodah, and HaMefaleys to which the older members were assigned, and a substantive training for status to make aliyah. They were the only ones who expected to obtain certificates from the tiny allocation that was received by the central HeHalutz office. The stay at the training locations was extended, in general from a half year to a year.

People began to enter the training units from HeHalutz in Zolkiew in order to be qualified for aliyah. Other people of Zolkiew went to Nadvirna and Lvov. At the conclusion of the training period, members attempted to secure their place in the list of those ready for aliyah, a matter of considerable achievement on its own. Only a few lucky people were privileged to receive this highly desired certificate. The first to make aliyah to The Land from the Kibbutzim of Avodah and HaMefaleys initiated started the settlements in Karkur, beside Pardes-Chana, and near another Kibbutz of the Stam HeHalutz movement in the Land of Israel.

After their success in this endeavor, the movement experienced hard times. The number of certificates continued to decline, and the members began to leave the training units and return to the branches. At the same time, crops in the Land of Israel deteriorated, and the danger of failure hovered over it because of the exit of members. In the end, this collapse did arrive because the Kibbutz did not receive added manpower from the Diaspora and the few who remained joined the Kibbutz of Eyn-HaMifratz of HaShomer Hatzair, which had been established beside Kiryat-Chaim, and today it is one of the largest Kibbutzim beside Acre.

The Zionist and the HeHalutz movements began a process to set up systems of deception to bypass the traps that the government of the Mandate had piled up to cease the flow of those attempting to make aliyah to The Land. The number of certificates of permission that were given to the Jewish agencies was nowhere in proportion to the strong demand by those in the youth movements who had prepared for aliyah. This also put pressure on settlements in The Land, which longed for additional working hands to assure its existence and continuation. This time was also the days of the first illegal attempts at aliyah. Initially this was a trickle, so that only very few were able to realize their dreams to enter its borders. Some of the methods of deceit included entering into The Land under the guise of being tourists, or as participants in the Maccabiah games that were to be held in The Land.

[Page 235]

In 1934, the ranks of the Jewish agencies, in coordination with the Haganah in The Land came to the conclusion that this was not the way to grow the settlement. Only a stream of a broad-based aliyah would create the impetus to build up the settlement. That was when the Jewish agencies removed their objections to illegal aliyah in order to broaden and sustain their goals despite the hidden dangers. This was the first of the efforts known as Aliyah Bet. Already in the first year, the first ship, a Greek vessel named Walus, departed from Europe, with about 400 Halutzim aboard. The ship sailed for a week until the passengers reached the shores of The Land. The passengers disembarked in the middle of the night and spread out without the English being aware of their presence. This success encouraged the backers of this concept and their energies to arrange for an additional voyage.

Once again, a living transport was crammed onto the same ship, the Walus, this time with 422 Halutzim from various pioneering movements in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Danzig, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary and Vienna. But this voyage was not successful for those making aliyah. The British shore patrol detained the ship as it drew near to the shores of The Land, and with gunfire, caused it to retreat from the boundaries of the Land of Israel. The ship attempted several tries in order to discharge its living cargo, but in the end, it was forced to retreat and sail to mid-sea. The Walus spent three months at sea until it returned to Europe. The Halutzim disembarked at the Polish-Rumanian border. It was the hand of fate that brought together so many young men from different lands to one place. They were united in one common concept only, which was the will to realize the dream of their own aliyah. That same fate, which almost brought them to fulfill their dreams and teased them with the glance at the land for which they yearned, carried them around until their strength gave out, and they returned them to their starting points. The Halutzim of the same Ship of Doctors, did not give up. They were privileged to get closer to the realization of their dreams more than their brethren, who did not attain their goal. They sat in a transit camp for three months, until in the end, they received certificates and reached The Land. Among the hundreds of pioneers on the Doctors Ship, Walus, there were two Halutzim from the Stam-HeHalutz branch in Zolkiew, and I was one of them.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 01 Sep 2024 by JH