|

|

|

[Page 730]

|

|

In prior chapters, we have stressed not only once, that Zamość is one of those ‘fortunate’ communities of Poland which has a larger cohort of survivors.

After the Nazi military defeat, the remnants of the wrecked ship begin to return, individuals, who managed to save themselves from the fiery flood of the Nazis.

Those came, who left Zamość in 1939 together with the Red Army, when the city, in accordance with the German-Russian Pact went over to the Germans. From the deep and faraway Soviet areas, they came to Zamość with the hope that perhaps they will find someone from those who were their near ones.

Those came, who hid in the forests, and bunkers; those who carried on a Marrano-like life under ‘Aryan Papers.’ They too thought, maybe, perhaps someone, just like them, somewhere, saved themselves during these dark years.

Those came, who survived the years of torture in the Nazi slave camps; came to cast a glance at their home, to see what and who might have remained from among their own; to learn of their fate.

This section – dedicated to the Survivors – in fact the last part of our Pinkas – is indeed the end of the sentence, the last resonance of our beloved home city.

Here too, we have the word of those who after the years of wandering, of fear and pain, came to their ‘home’ and found there what they found – pain and desolation….

They, the remnants of the people who were not slaughtered, have the word here. Also, their tales, their portraits are given here without modification, without commentary and interpretation.

Here also, we made use of the entire material that we had at our disposal. Everyone who had something to tell obtained the opportunity to do so.

(From the reports of Chaim Shpizeisen, ע”ה)

|

|

Moshe Zeydl (Szczecin); Aharon-Mordechai Hirschberg (Lodz); Chaim Shpizeisen (Szczecin); H. Sukhaczewsky (Lublin); Moshe Kezman (Wroclaw); Leibl Werter (Niemcie); Josef Szyfer (Szczecin); Elyeh Rechtman (Wroclaw); Chaim Untrecht, Shlomo Fang, Aharon Miller (All 3 Legnica); Mottel Katz (Zhary); Eilbirt from Browar, and Simcha Gringler (Swidnice).[1] |

|

|

Among those participating: Anshel Zimmerung, the grandson of Meir Maler, of the city (Lublin); Shimon Bajczman, Josef Szyfer (Szczecin), Shlomo Bukh, Pinhas, Khaskel Shamash's son (Wroclaw); Levi Gringler, butcher |

As soon as Zamość was liberated from the Hitlerist occupation, an inquiry about the condition of Zamość and its Jews arrived from landsleit in New York, signed by Israel Zilber, at the address of Eliyahu Epstein, who had survived the period of the occupation in a hideout.

The letter laid without being answered. It was only when the landsman, Jekuthiel Zwillich returned from the German camps, who made a connection with the Zamość Help Committee in New York, was contact first established. Contact also was initiated with those residents of Zamość who had been saved, who surfaced, and came from a variety of places.

A short time after the first connection, the Zamość committee received from New York the first assistance of $150 dollars.

The Committee rented a location, which was supposed to be a lodging point for the people of Zamość who were thrown together, and they were also given a small amount of support.

The Committee consisted of: Elyeh Epstein, Shimon Bajczman, Jekuthiel Zwillich, Shlomo Bukh and others.

This was in the end of 1945 and beginning of 1946.

In the spring of 1946, when the war refugees began to arrive with the repatriation echelons, and those who were sent off to the Soviet Union, residents of Zamość began to return en masse. It happened that fate was such, that the proportion of those who came back that were from Zamość, was a significant one. Many from Zamość, in their time, in the year 1939, when Zamość ‘voluntarily’ went over to the Germans, were able to evacuate themselves with the Red Army, and a part of them went off deep into Russia, and applied themselves to work in many factories and undertakings.

The echelons of the repatriated went to Lower Silesia, the so-called newly constituted Polish areas, which had belonged to Germany. In many cities and towns, of these tracts, people from Zamość began to meet one another. They came in almost every echelon. Rather significant groups of people from Zamość began to develop in the cities of Upper and Lower Silesia, in Lodz and Szczecin, the former German port cities.

[Page 732]

Each individual wanted to know details about their own relatives; who had saved themselves; where they are to be found. From this a need was created for an information center, which could dispense information, which would enable families to get in contact and indeed, should be able to provide some of the initial advice and assistance.

Committees were organized all over, of the former residents of Zamość. In Szczecin, the committee constituted itself in May 1946, and it consisted of the following landsleit: Mendel Sznur, ע”ה (died after making aliyah to Israel, in Haifa), Chaim Shpizeisen (Died in Tel-Aviv), Josef Szyfer, Moshe Schliam, and others. At that time, in Szczecin, about 1,000 people from Zamość registered themselves. A list of those registered was immediately then sent to New York. The list was printed in a newspaper. Thanks to this presentation, many friends and relatives responded and made inquiries.

The American Help-Committee sent assistance frequently to the committee of the Zamość people in Szczecin, Lodz, Wroclaw (formerly Breslau), which was divided up among the landsleit.

On November 1947, an assembly of all the Zamość committees in Poland was organized through the central committee in Warsaw in the capitol city of Lower Silesia – in Wroclaw. Up to 30 delegated traveled to come together from a variety of cities.

After the reporting and a discussion about the future activities, it was agreed that:

The future activities need to be dedicated to carry out a wide-ranging exhumation – to bring to proper burial those dispersed and scattered remains of the martyrs in the area, who had been interred in a variety of places, in and around the city. To gather together all of the grave stones from both Zamość cemeteries, which had been uprooted from them, and with which an array of streets in Zamość had been paved. From these desecrated grave stones, a monument is to be erected. To put the cemetery back in order.

A central Zamość committee of survivors was selected, of those who were to be found in Poland. It was decided that the leadership office would be located in Szczecin, where the Chair, Chaim Shpizeisen was located, the Treasurer Moshe Zaydl, and the Help Secretary Josef Szyfer.

At our call, the Zamość people in New York responded very warmly, with the landsleit Israel Zilber and Izzy Herman at the head, and from Buenos Aires the landsleit, with the assistance of Wolf Kornmass, Kossoy and Tzitzman at their head.

Thanks to this received assistance, the exhumation was carried out in January 1949. 96 martyrs were given a proper Jewish burial. There is no doubt that the number of martyrs was larger. However, we exhumed those, where we knew the location where the murderers had killed them.

The difficult technical work was carried out under the direction of the delegate and member of the Zamość central committee, Josef Szyfer.

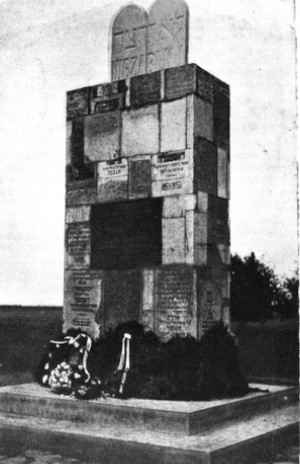

In the summer of 1950, the grave stones were gathered together at the cemetery, and a monument was erected, and a common grave was bounded with the grave stones that had been gathered in this fashion.

The technical work was supervised by delegate from the Zamość committee, the landsman, Shia Stein.

It needs to be said, that the far-flung people from Zamość in their respective ‘new’ locations, found it difficult to participate in the work of bringing order to the grave stones, and the erection of the memorial. Szczecin, where larger numbers of landsleit were located, is on the other side of Poland. The travel was not easy at all. The Zamość people who were closer (whether in Zamość itself, or from Lublin) were less involved.

[Page 733]

On September 10, 1950, an unveiling of the monument took place, which was indeed put together from the desecrated stones. It is found on the cemetery, not far from the common grave of the exhumed Jewish martyrs, brought from the surrounding villages, fields and woods.

To the unveiling, came Jews from Zamość, survivors, who then lived in Warsaw, Lublin, Szczecin, Dzerzhonow, Wroclaw, and other points.

The monument was unveiled in the presence of an array of central and local institutions. The Zamość land committee was not then represented. The political situation in Poland no longer permitted the existence of such societies and organizations.

At the unveiling, the Chairman of the Lublin Jewish District Committee spoke, M. Adler; from the Zamość District committee, from the United Polish Workers Party – Zhalinsky; from the central committee of the Jews in Poland, and from the Yiddish Historical Institute – V. H. Ivan. Floral wreaths were laid by a variety of organizations and societies.

The monument was designed by the architect-engineer Adam Klimek, with the close help and oversight of Joshua Stein, who in his time, was delegated by the Zamość committee about this matter.

The Zamość Survivors Organization, had, in the matter of a scant five years, discharged its important and positive work. While it is true that the number of our landsleit was equivalent to that from much larger cities, much help was required. Also, the committee played an important role in unifying the sundered families that were separated in various places. There were instances, that members of families were found, who were thought to have been killed. The Zamość committee were clearinghouses of addresses for all the far-flung landsleit who were driven away during the Holocaust.

Not only for those from Zamość, but also survivors from the surrounding towns depended on the people from Zamość. Very often, indeed, there were those people, who had family and relative connections with Zamość.

From 1950 onwards, the existence of the Zamość society was not possible and not necessary.

Translator's footnote:

By Jekuthiel Zwillich

|

|

Among the participants: Shlomo Bukh (Wroclaw); Anshel Zimmerung (Lublin); Josef Szyfer (Szczecin); Levi Gringler (Szczecin); Shimon Bajczman (Zamość) |

Together, with a large group of Polish, Hungarian, Czech and German Jews, we were liberated from Theresienstadt on May 10, 1945, when the Russian troops took control of the area of this large ghetto-center.

A few days after our liberation, news circulated within Theresienstadt , that the Poles are treating the Jews who survived very badly – that they have shown themselves to kill many of the Jews, who remained alive after the Nazi slaughters, and that in the evening hours, Jews are not permitted to show themselves in the streets.

Two weeks after our liberation, two men arrived in Theresienstadt from Poland, who presented themselves as being sent by the new temporary Polish people's government. The gave speeches, and declared that the Theresienstadt camp was being liquidated, and we are leaving the city. They called upon the Jews to come back to Poland and to rebuild the new Poland of the people. They told us that from time to time, indeed there were attacks by the ‘A.K.’ (Armia Krajova) against the Jews, but this sis severely resisted by the Polish People's Regime.

They advised us, that the Jews should travel to formerly German territories, which had been robbed from Poland. There, houses and businesses of Germans wait for us, who have been chased out of Poland. The Jews are permitted to take up residence there.

We, the group from Zamość, decided to travel to Zamość, despite the fact that we already knew that we no longer had anyone left in Zamość. Each of us privately thought, who knew, maybe?…. maybe, despite everything, we will find someone from the family in Zamość.

On a certain day, a transport of Jews left Theresienstadt for Poland. The transport went to Krakow, and when the transport with the Jews arrived in Poland, we, the group from Zamość, debarked from the train and with a second train, we traveled to Lodz.

In Lodz, we rode over to the Jewish Committee. In the yard, where the Jewish Committee was located, there already were a large number of Jews from a variety of forced labor camps, and on the walls, the names of many Jews were listed, who were looking for their relatives. We made our way to the Jewish Committee for initial assistance. Everyone received 75 zlotys.

On the second day, we took the train to Zamość. We arrived in Zamość at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. We saw the first sign of the war in the fact that the train station had been wrecked – all that remained was the foundation. By contrast, the city, the houses, didn't suffer at all – everything remained intact.

The city looked like it was a Saturday afternoon of years gone bay. The streets, empty. We did not know where we could enter. So we remained standing in the corner where the porters used to stand. We stood like this for more than an hour, until someone from the Poles told the Jews, that were already in Zamość, that additional Jews had arrived. Several Jews then came out to us. All the Jews were very happy to see us, and each took one of us to them. Joseph (Yossel'eh) Shpeizman took me to him. We were told immediately that it is better that we should not go out into the streets at night…

Almost all of the businesses were open. Among them, many restaurants, beer gardens. The merchants of the businesses were all Poles, apart from two businesses, which belonged to Jews – Elyeh Epstein's pharmacy, and Fink's ironmongery.

[Page 735]

The only way to trade was in the marketplace, where the wagons would stand before the war. The market was set out with stalls and carts with a variety of goods – you could buy anything from a bit of parsley to the finest German suit. The largest number of the merchants who manned these stalls and carts consisted of railroad employees, watchmen, and former prostitutes. These ‘vendors’ would always travel to former German cities, which Poland had taken back, and from there, bring packages with a variety of merchandise and sell it in the market.

Poles live in all of the Jewish houses – a large part of them are from the eastern provinces. All are already settled in, and all the houses into which I came, one could see many pillows…

The first question from every Pole that we knew, was:

Pan zyje? You're still alive?

And told me at the same time, that he rescued a Jew.

All the Poles were haughtier and gleeful. Every one of them told me, let the Russian leave Poland, and we will build a new, beautiful Poland… (In that time, the Poles believed and hoped that the Russians will leave Poland rather quickly).

The City Elder and his appointees were located in the home of Avigdor Inlander. At the house of the Olejarz[1] was the Polish Old Age Home (Dom starców). The Magistrate had made a museum out of Sznur's house; I was in the synagogue. The synagogue looks like it was after a pogrom. No benches and no candelabras; boards of wood and iron are strewn about; in the middle of the synagogue, where the Bimah stood, there was a deep pit, seemingly, they sought Jewish treasure there….

The Great Bet HaMedrash was closed. From the street, it is possible to see that the windows and the transoms are knocked out.

Poles live in the shtibl where the Shammes of the Bet HaMedrash lived (Daleh's), and also in the little Bet HaMedrash, where the Holy Ark stood, with Torah scrolls, a crucifix hangs with ‘religious icons…’

On the Schulhof, where Shmuel Dicker used to live, there is a restaurant today. Every night, one hears drunken shouting coming from there.

On the second day, I went to the cemetery. First I went to the old cemetery. When one arrives there, it makes the impression as if someone had the hair shorn off their head. An empty place, without head stones. There was not a single trace left of the cemetery that had been there. Also, the wall that served as a border with the ‘Nalew[2]’ was taken away.

Later, I went to the new cemetery. Thanks to the fact that I recognized the Tahara cottage, I apprehended the fact that this was the location of the cemetery. The Polish gravedigger lives in the Tahara cottage. Here as well, there were no traces of the cemetery. No fence, no head stones (mounds, with signs written in Yiddish). These were fresh victims, those whom our Polish ‘good friends’ had manifested themselves to kill after the war…

[Page 736]

Several days later, I had the occasion to be on the new streets – Krasniczynskowa, near Garfinkel's house – and I saw that the entire sidewalk there was paved with the head stones from our cemetery. With the letters facing upwards. I stood for a long while, reading the names on the head stones.

I later spoke with the Jewish Committee, which was found in Zamość. I made them aware of this abuse, that the headstones were subject to this desecration.

Several days later, the committee set up a platform with 2 Polish workers and I. We assembled several platforms with the head stones, and took them off to the old cemetery. On the second day, Elyeh Epstein approached us, and advised that he did not have any money for this purpose, and the work was stopped.

A couple of years later, thanks to the fact that our landsmanschaft in America had send in money, we assembled all of the head stones, from wherever it was possible in the streets, and from them, set up a handsome memorial on the new cemetery.

I had several occasions to be in the Neustadt. The Neustadt suffered a great deal from the war and the Holocaust. Many houses were missing from the marketplace (Rynek). On the Hrubieszow Gasse – on both sides – only one or two houses remained. As a memorial, that Jews had lived here in the Neustadt, there is the foundation of the synagogue… in the streets and in the marketplace, one does not see a single person. At the place opposite Janacek's, several Polish storekeepers sit on boxes, and they sell vegetables and fruit.

Because of this, large fairs take place here every Thursday. Many peasants come together from the villages. It gets so crowded, that it is difficult to pass through the marketplace. At these fairs, it is possible to buy everything.

In Zamość, I then ran into several tens of Jews. Part of them came from the forests; part had lives on ‘Aryan Papers;’ part had been liberated from the Czestochowa camp ‘Hassag[3]’ and also those who had come with the Red Army from Russia and afterwards already remained in Zamość.

All these Jews lived in the Altstadt. They live on ‘one foot.’ Not one of them thought to remain in Zamość. Every one had come for a long as they could sell their house, or inheritance, and immediately depart.

I also met Jews from the surrounding towns, among the Jews that I encountered in Zamość, because they were afraid to travel into, and remain, in those towns. When a Pole wanted to purchase a hose from a Jew in such a town, the Pole would come to Zamość. The transaction was consummated in Zamość.

A Jew from Szczebrzeszyn told me:

He traveled to Szczebrzeszyn. Young gentile children ran after him, and shouted ‘Zyd’ at him, and threw stones. He was lucky that an auto was parked on the marketplace with two Russian soldiers in it. He pleaded with them, and they took him to Zamość.

At that time, the transports with the repatriated Polish Jews began to arrive from Russia. Among them were also many Jews from Zamość. They came very impoverished. Every time a second Jew came to Zamość, sells his inheritance, and again, travels on. The Poles used this circumstance, in which the Jews found themselves and bought the Jewish houses practically for nothing.

The first letters arrived in Zamość from our landsleit in America. They inquired about the fate of the Zamość Jews, and at the same time send us $150 dollars. The committee divided this money among all the Zamość people.

Letters and packages with clothing also arrived from our Zamość [landsleit] in the Land of Israel.

The Jews grouped themselves near the synagogue in Zamość, where Lieber Emmer at one time had his restaurant. When the Poles wanted to buy something from Jews, they knew to come to the synagogue.

From time to time, Polish coachmen would attack the Jews, insult them, and beat them. The Jews had no option, and they went away from the synagogue, and grouped themselves opposite the Magistrate Building, near Rann's business.

[Page 737]

However, here too, two Polish wagon drivers would come all the time and attack. They rode on a platform, and when they rode by where the Jews were standing, they would stop their platform at the side, and would accost the Jews with a whip, abusing and beating them. The Jews, when they would see these hooligans coming from a distance, would run away.

One time, I was standing with a group of Jews, and we were telling each other about what we had lived through during the war. These hooligans came riding up. The Jews fled, and only I remained standing. The two hooligans accosted me, abused and beat me with the whip, until they broke the whip. I immediately went to the police, and described this, and I took off my shirt and showed the marks that the hooligans made on my back. The police immediately arrested the hooligans, held them for two days, and then set them free.

At the same time, the pogrom in Kielce took place. I believe that because of this, a Polish captain came down to Zamość, and he called several Jews to the Magistrate, and asked them a variety of questions about the beating.

Several days later, the police again arrested the two hooligans, and also several Polish merchants. It appeared that all these attacks had been organized by the Polish merchants.

A day before I left Zamość, I was called before the investigative judge about the issue, and I was asked about a variety of details of the attack.

They told me, that the hooligans would be sentenced shortly.

I have no idea of what conclusion the court came to, because I left Zamość, and I was no longer in Zamość.

Translator's footnotes:

By Moshe Schliam

Three weeks after my return from Russia, where I had spent the war years – to Poland. The echelon of repatriated persons brought us to Szczecin, a port city on the Baltic Sea, was co-opted into Polish sovereignty. I felt a need to visit the city of my birth, Zamość, which I had left at the time of the Hitlerist invasion, in October 1939.

The bloody tragedy of the entirety of Polish Jewry, and among them, of our city of Zamość, was already known to me while I was still in Russia, but despite this, preparing to leave Poland, I felt an obligation to visit our city; to see with my own eyes, the destroyed Jewish community, and perhaps I will find some sort of a trace of my dear relatives?…

We arrived in the city on May 10, 1946 (I and Joseph Dickler). It was a Friday's day, and our hearts immediately experienced a flutter. The streets were empty, as if they had died, around the ‘little orchards’ – empty. What happened to the life of this part of the city? Circles of people would gather constantly in this place, the older ones would conduct business, and the younger ones would be having fiery discussions about a variety of problems.

We walk by the businesses, of which 90 percent were at one time in Jewish hands, and now – all are owned by Christians. We go through the alleys, the streets. It is intact, the streets and the houses, as they were, however, the Jews are not there.

We walk like mourners, our faces dark, we search for a Jew, where we might can put out first foot down, and, here, we see from faraway, two women, and we think they are Jewish. We draw closer, and we see Freydeleh Fink who was saved by a miracle from the hands of the Hitlerists, and her daughter, who has not long ago returned from Russia.

We learn from them that an assembly of the Jews in Zamość is taking place at the Basilianska Gasse 61 (Foont's House), in the house of Yakkel Schatzkammer of the Neustadt (who also survived by a miracle).

With beating hearts we go to the gathering. – Whom will we meet there? What sort of issues will be addressed?

We meet about 30 Jews assembled there – remnants of families cut down, shadows of people, there is nobody among them who has settled, or has come to settle in the city. All have come in a hurry to liquidate their inheritance holdings – and to flee from here.

Only three Jews continue to run their businesses: Elyeh Epstein – his pharmacy store, with which he does not wish to part; Freydeleh Fink – the ironmongery, and Shmuel Rosen – His Beer Garden.

How long they will be able to continue to survive is unknown, the place repels Jews from here, they cannot live here. The blood and the tragic murders of martyrs screams from the earth.

As if in an hallucination, we go, unable even to weep; our eyes have been dried of tears for a long time already.

At the assembly, it is recalled that a year ago there were still 300 Jews, among which about 30 had survived by a miracle from the brutal death, and the rest, who returned from Russia. However, none of them can remain here for any length of time. True, it is now quiet in the city, one does not hear about attacks against Jews here, however, Jews who were born and raised here cannot make a fresh start here, just like one cannot remain from a longer time in a cemetery.

A committee of the Jews is selected at the meeting, who are now found in Zamość. In the agenda of the committee:

As one who had only recently arrived, and had no notion of what had transpired – I ask:

– Is it not part of the activity of the committee to safeguard to assets of the destroyed community, with all of its material and spiritual treasures?

Has the Pinkas of the Jewish community survived?

And where are the books, the valuables, with their historical value, which had been located in the former Bet HaMedrash?

Where are the documents. The minutes, lists of the Jewish libraries, schools, parties, organizations, cultural and philanthropic institutions?

To this, I receive the answer that there was no possibility to protect them – because no trace of any of them remained. The buildings of the Jewish community – part of them destroyed, and the rest taken over by Polish institutions, banks and schools – the specifics and general [possessions] of the Jews in the city, have been robbed by strangers.

On the following morning, we could review the factual nature of the picture of the we received at the meeting, with our own eyes.

Night falls in the meantime, and we go out into the streets , and look into the lit windows – no trace, no remnant of that renown Jewish Sabbath – no Sabbath candles are to be seen, that were blessed by Jewish mothers in the Jewish homes, the Sabbath and Festival-loving Jews are no more, so beautifully portrayed by I. L .Peretz. We walk sadly past the wreckage of a Jewish life, which was so deeply rooted here and which angry winds and evil beasts in the form of humans tore out by those roots….

We run through the streets as if being pursued, and into our own residence. Mr. Elyeh Epstein, who lives in Bajczman's house, together with Bajczman's oldest son, Shimon, have invited us their for a night's lodging.

We talked with Elyeh Epstein at length – who told us about his personal experiences in living through the time of the bloody German invasion. We hear a portrait of blood and tears, until deep into the night. It is clear that after such bitter impressions during the course of the day, our sleep was impaired in that first night of being in Zamość, after an absence of more than a full 7 sorrowful years. Before our eyes, we beheld those dark images of vandalism and barbarity that overtook our near and dear ones, carried out in the twentieth century in the so-called ‘progressive’ epoch, by the ‘cultured’ German nation – is there even a form of vengeance for something like this?

In the morning we go to the ‘Hayfl,’ to the house where I was born, and where I had left my near ones behind, when I set out on my road to wandering.

I talk to the shoemaker, the gentile, who lives in the house, perhaps some trace has remained in the house, a sign of our nearest and dearest, perhaps a picture, a handwritten document, and address?

There is nothing. He is not the first person to live in the house. The tenants were changes many times, and he has found not a thing.

[Page 740]

And so we go through a number of homes in the ‘Hayfl’ and we find not a trace. In the large yard, children are playing – What has happened to the Jewish children, whose joyous laughter, and lively play always filled this yard?….

We enter the Zamość synagogue. It is one big wreckage. The windows are broken in, and boarded up, the doors are nailed shut – this is the appearance of the Zamość synagogue, with its famous architecture, we cannot even go in here…

We go to the old Jewish cemetery – the only thing that remains is the hedged fence, the head stones are not there, the field is p-lowed and cattle graze on the grass….

The new cemetery looks like this also.

Later on, we found part of the head stones, they had been used to pave the sidewalks of the new streets, near Garfinkel's house, as near the castle keep, near the Justice Buildings, they were covered in cement – and when the cement is washed off, the Hebrew letters re-appear on the memorial stones…

The barbarians! They didn't even have any decency towards the dead, and permit them rest!

How the Jews were exterminated, the various brutal ways in which the extermination was accomplished, the ‘evacuations’ and the extermination camps, about them there is the eye witness accounts of those who lived through it – who with their own eyes saw the bloody train of the Hitlerists in Zamość – I will not write about them. It suffices for me that not one person from my entire family did not survive!

These few days, that we were in ‘Zamość Without Jews’ were a reliving anew of the darkness of the bloody years.

We left with the decision that the faster we could leave the bloody Polish soil, where that populace that had been born there, lived together with Jews for hundreds of years, had for the most part, with a tranquil foreknowledge, assisted the implementation of the mass-murder and bloody extermination of the Jewish population.

% what Amalek did to you! These barbarous actions will never be forgotten!

By Sholom Stern (Montreal)

|

On a winter's eve, between houses with windows,

In the marketplace swarm that has been silenced

On the lofty tower clock, the hands are shadowed,

Shadows race through the darkened yards.

One who is late, drives, applies

In the Bet HaMedrash, in Shtiblach,

The candles of fat quarrel and sputter.

The market is done, the swarming is done. |

[Page 742]

|

The bridge and the gate are locked. Peasant and fear have swum away. Sideways are darkened and silent, And over open Gemaras, Jews with wind-blown beards Sing-song and intone Saddened, and sunken in thought.

Faces are blinded.

And until late in the night

And the tall shadow of Yohanan Wassertreger sunk in thought

Softly and with heart, he intones a song,

And the pullers of cobbler's thread, and the needle sewers,

Reverberating clock bells

Seemingly, his walk is thought out. |

[Page 743]

|

But here, on a slippery threshold A woman cries out and curses. Peretz remains standing, and He is drawn to the plaintive cry Of a small scrawny little boy, Who shivers in the cold And whimpers out, that this Is his stern stepmother driving him From his father's house.

The little boy wails:

Peretz's face is lined with sorrow,

Peretz takes him by the hand,

In the fore-kitchen, the little boy

It is quiet in the house

The bridge is raised, locked. |

[Page 744]

|

In the summer suns

The Nazi-Murderer

There is nobody anymore.

Silent places of business, darkened streets,

On bloody byways,

And on the municipal thoroughfare

And hands protrude |

[Page 745]

|

And between ash and smoke, Yitzhak Leib Peretz walks All alone in the land of destruction And wails his cry Over the unspeakable calamity.

Peretz blunders between destruction and thorns

Nazi slaughterers,

Yitzhak Leib Peretz wails |

By Helena Schaffner

When, in the fall of 1945, I traveled to my Zamość, I knew that I will not encounter any relatives, friends and acquaintances. I felt a profound need to see my home city once again. I thought: perhaps… remnants, I wanted again to breathe in the Zamość air, feel something close to me, my own.

The train from Warsaw to Lublin was packed. Unlit, cold. Full of sacks and with new Polish post-war traders, who sat sullenly, glowering at one another.

At Lublin, the train emptied out. In the car, apart from me, only a young man remained. We did not exchange a single word. I did not want to speak about my Zamość with a strange Pole, knowing at the outset, that not only will he not understand me, he will not want to understand me. The train dragged itself along lazily, stopping at bare, dead stations. With a beating heart, I waited for the Trawniki station. This was the place where the workers from Schultz's factory in the Warsaw ghetto were brought and killed, the people that fate had tied me to for a while – from July 1942 to February 1943 – when I worked together with them.

Trawniki…

I descended from the train, and asked the overseer of the station, where Schultz's factory ‘work camp’ was located here (the death camp). He cast a heavy glance at me, and apparently, taking me for a Pole, called out in wonder:

– But, there were only Jews there!

At that moment, someone touched me on the hand. I turned around, and saw the young man from the train near me. He asked me to return to the train, because I could remain alone on the station and have to wait overnight for the next train through. When we were again sitting in the train car, the young man called out to me:

– It is dangerous to stay here. The populace is hostile to Jews.

What Jews? – Those who aren't here? I thought for a moment – and why is this young man moved to warn me in such an intense fashion?

I immediately became aware that he is Jewish himself, and that he and his family had lived in Zamość until the outbreak of the war. He knew who I was. Also, a little later, I recalled that I had seen him one time, as a student, he was a colleague of the young Peretzes. He saved himself, fled to Warsaw, and there married a daughter of Polish people, who hid him in their house. When he took sanctuary in the church, he felt fortunate – he saved his life. Is he happy now? – I didn't want to ask him, but from his silence, and his sadness I sensed that he is now thinking about Zamość, to which the train was now taking him, about his destroyed Jewish home, and about the peculiar ways of fate…

Silently, we sat in the wagon, when the train stopped in Zamość. It was a foggy early morning. The station lay enveloped by a deep silence. No carriage could be seen. We both went into the city on foot. And again, we are greeted by a silence, a deep one, an ‘unnatural’ one; a silence which one can, it would seem, touch with one's hand. The houses, the streets, the city square with the municipal building in the middle – everything stands as it was before, but it is ossified. Zamość did not suffer externally from the operations of the war, and not during the aktionen. But the deathly silence that I encountered, was so disassembling, so suffocating, that one thought that the air had been expelled from here.

As we approached the municipal building, the young man took his leave of me. He had come to Zamość with something of an official mission, and had to travel back to Warsaw on that same day. He did not tell me his name now, as a Pole,

[Page 747]

he did not want to meet anyone. It was very clear that he had no desire to return to that which once was. He had severed his ties to the past. He had to sever his ties. I, by contrast, wanted to immerse myself in it.

For a bit of time, I wandered about the streets and byways; looked into the gates of the houses, that were so familiar to me; went back and forth through the ‘potchinehs,’ – an unease peered out at me from all about. I came in contact with strange people, who looked like shadows – I felt that I was the single living person in a cemetery.

Nobody stopped me, and I also did not detain any of them. After a bit of time, I began to think that I myself am no more than a shadow.

I went off in the direction of the marketplace. There, an elderly Pole who was leading a cow, drew close to me.

– You, madam, are the daughter of the elderly Ashkenazi?

Whether he was happy that he had espied a familiar Jewish daughter, or whether he wondered how such a thing could have occurred? – I could in no way read the answer to this from his face.

I went on further.

On the same day, I learned that there were perhaps a minyan of Jews in Zamość. Several, who had hidden themselves on the Aryan side, individuals who had returned from Russia and a couple of Jews from surrounding towns. This shred of Jews, sundered, cordoned off from equitable treatment, waited for some sort of miracle: something has to happen, it is necessary to wait. They have to be somewhere, the Jews of Zamość, all the kin, that lived, worked, traded, were happy, sorrowed!…. They will return, they must return!…

And perhaps they died? – I went off to the cemetery. The wall was torn down. I did not encounter a single headstone. The field was full of pits. I could not even recognize the grave sites of my relatives. All I saw was that, to one side, there were several fresh mounds. A young Jewish man, who was saved himself by a miracle, who escorted me to the cemetery, told me that under these mounds, Hessia Goldstein lies buried (the sister of I. L. Peretz), whom the Germans shot in bed, where she lay ill; her son, who during the selektion, had resisted the Germans; his wife, and his child. The burial was carried out by the couple of Zamość Jews who had remained after the ‘action.’ These mounds, which were still fresh, were the single surviving sign of [the remains of] the Zamość community from the Nazi times.

I left the old cemetery, which was located between Zamość and the Neustadt. In place of the cemetery, I saw before me a large square paved with cement, and smooth as a mirror. I was aware, that the Germans had transformed the old Jewish cemetery into a parking lot for their freight trucks.

I went back to the city, and I saw new streets, built between the city and the engineering-garden, which had been paved with the grave stones of both cemeteries.

Again, I ricocheted around the city. I passed through the Peretz Gasse in the direction of the synagogue, which had been desecrated by the Germans – the windows smashed out, the doors – nailed shut. (The efforts of the Jews living in the Hayfl to put the synagogue back in order, encountered difficulties from the municipal administration).

Despite all this, I did not want to give up mt hopes to find some further traces of the Zamość of yesteryear. At a moment, it seemed to me that I am about to find them. That occurred when I passed by the cinema theater, which was in the building of the former Franciscan church. There, it was always full of Jewish youth, or so I thought. I bought a ticket, not even looking at the program, as to what was playing, and I went inside. It was cold. I looked around. Almost all of the seats were empty. There were barely twenty people on this enormous hall. Around and about – an emptiness, a barren cold, a terrifying darkness. Frightened, I made my way outside.

[Page 748]

Night fell. I went to spend the night with one of the surviving Jews. There were three of us there. We knew each other from times gone by. It seemed as if we had a lot to tell one another. However the city, that was struck dumb, the silence, which hung everywhere, locked up our mouths. We sat and were still, each sunken in the past. What was the purpose of speaking? The fact is, the single and ineluctable one – there are no more Jews in Zamość.

I decided that immediately on the morrow, in the morning. Zamość. I was advised to travel to Lublin by Freight truck, and not by train. This way would be quicker and safer. Two Jews escorted me to a side street near the municipal building and there, they took their leave of me. Nobody needed to know who I was, and what tied me to Zamość… I left Zamość at nine o'clock in the morning. It was a cold, dry morning. The city looked like it was shrouded in sorrow. When the freight truck turned in the direction of the Lublin Road, I threw a last glance at the ‘potchinehs,’ at the beautiful building of the church, at the bell tower, at the municipal government building. We went out onto the highway – the hospital went by the eyes, the Lublin outskirts, the prison, the barracks. Afterwards, flat land came, and silent hills sunken in thought.

I was still in Zamość with my thoughts, when the driver called out: Izbica! I did not see a city, only wreckage. The eviscerated, bullet-scarred walls looked like congealed pieces of horror. It was in this place, that a portion of the Zamość Jewish populace was shot and burned together with the Jews of Izbica.

This was the last image, that has eternally remained in my memory from the post-war visit to my home city of Zamość.

By Akiva Eierweiss

|

‘…. and he, what did he mean? He, the one who chose you. Was this his punishment? Was he lacking in wonders? Why does he not say stop!…’. |

|

|

Lo, these very words, from the Jester in ‘At Night on the Old Marketplace’ by I. L. Peretz, wormed their way into my mind when, in the month of March 1946, a year after the liberation already, I stood inside, in the ‘heart’ of the Zamość ‘Rotunda.’

Before me, I saw a massive mound of half-burned human bodies – fused bones, heads, feet torn of, still in their boots, hand bones in sleeves… look, they are still fresh, the victims of the beastly killings.

One could still smell the essence of the smoke. Here, in a corner, there lie additional rows of wood, half-burned. Plies on piles, and pieces of skin between them, that had not been burned…

It appears that the murderers were abruptly stopped in the middle of their cannibal feast…

We, from Zamość, know the ‘Rotunda’ very well. The old building that traces its origin to the complex of the former fortress, which served as a powder magazine, it was also called ‘prokhovnia.’ Stout, red brick walls, without a roof.

Here, in the ‘Rotunda’, diagonally opposite the train station, was a good defense point. In olden times, when the citadel was a part of the fortification around Zamość, there were deep trenches still here, which could be filled with water, in order to make even more difficult, the passage of an enemy that wanted to attack.

It was this place that the Nazis elected, in order to carry out their sporadic and systematic acts of murder. They dug out a pit in the middle, and there, they installed a primitive crematorium. They shot the victim, and immediately cremated him on the spot.

Whoever went into that place, no longer ever came out. In this manner, hundreds, and thousands, took along with them, the secret of their last journey…

The criminals could not break apart the primitive crematorium, which they installed, could not make it seem like they had wiped off its traces. It appears that these ‘heroes’ who displayed such ‘heroism’ against those who were tortured and starved Jewish mass that had been spat upon, had to draw back rather quickly, and leave behind evidence of their bestiality.

The ‘Rotunda’ was not the only extermination point of our 14 thousand residents of Zamość, and the many thousands of Jews who were brought to Zamość from all parts of the world. The majority of our community was annihilated in the various extermination camps – firstly in the death factory Belzec, in Majdanek, in the marches to Izbica, and other places.

In the crematorium of the ‘Rotunda’, the blood and the bones of non-Jews were intermingled, annihilated by the Nazis.

The essential point: The ‘Rotunda’ remained in Zamość, here it is like a witness of the horror; it is a permanent indicator of the bestial murders committed by the brown hordes.

[Page 750]

During my visit, the area around the ‘Rotunda’ was filled with graves, many out of necessity, symbolic, on small crosses, the names of those who were tortured were either written or scratched.

On the red ‘Rotunda bricks’ I also found, written in Yiddish, and in Polish, many names of the Jewish victims….

It is spring, a golden Polish spring, March 1946. The promise of rebirth is carried in from the fields and woods; birds are building nests in the gouges of the pock-marked walls of the ‘Rotunda.’…

And we, the tortured remnants of a community that once was, stand and inhale the stench of burned flesh, smoking bones, and it is not the song of birds that reaches our ears – we hear the plaintive cry of the ones who were tortured.

Let the ‘Rotunda’ not be wiped away – let it remain for all eternity as a memorial that should remind us, and also demand of us.

By M. Tzanin)

…Before the deluge that cascaded over Polish Jewry, sixteen thousand Jews lived here, craftsmen, and merchants, workers and storekeepers, and a large Jewish intelligentsia. In the fortress city, there were yet two fortresses which had a much greater influence on the Jews than the mortared walls and forts that hemmed Zamość in: Hasidism and the Enlightenment.

There was a rich Jewish life here. Thereby, as was the case in all cities, the Jews of Zamość also dreamed about better worlds, about redemption, and the youth sacrificed its life for that better world, which never arrived for it.

Zamość had within it a large socialist movement: the battles between the Bund, Poalei Tzion and the communists were so fiery here, so angered, it was as if fate had decreed that they alone had to build the ‘new’ world, as if they were the very foundation of socialism…. Were they, perhaps, that foundation? Were they, perhaps, right?

Beautiful Zamość now gives the impression of a theater, where the stage has been set with props for a medieval city, with the old marketplace and artistic buildings, but the audience has not come, and the actors have no one to whom they can show themselves to…

Zamość is half empty. In the Neustadt, which the Jews built up before the war, a kilometer further away from the center, two Jewish families live today, without children, just two people. That is all that remains of the rich Jewish community.

When I stood next to the synagogue on Peretz Gasse (the name remained even through the times of the German occupation), a Pole, in military dress, came over to me, and inquired of me in the following manner:

– Herr Professor, what are you looking for here?

– I am looking at this building and I do not know what it is – I answer him.

– Ah, the Herr Professor certainly must be involved in the research of old structures? – He asks with curiosity, and I decide not to lead him off erroneously.

– Yes – I say – I am researching medieval items, and I am curious to know what sort of building this is.

– This is – he says – the old synagogue. Here is where the Jews hid all their silver artifacts and vessels from all the synagogues in Zamość. Come in right here – he indicates the entranceway – you will see something.

And I see a deep pit with the surrounding construction of a tunnel. Underneath the tunnel is spacious, and in the darkness, one cannot see its end. My informant clarifies for me, that this tunnel was built back in the times when the Zamoyskis ruled, and it stretched for a distance of many kilometers, to the city of Krasnystaw. The Jews took advantage of the fact that the synagogue was built over the tunnel, and they dug down to it, and hid their Torah scrolls and the silverware of the synagogue there. The Germans turned the synagogue into a granary, but the people of Zamość knew about the fact that treasure was hidden there. Now, when the Germans left the city, and the Russian Army had not yet taken over the city, the people let themselves at the synagogue, and with picks and shovels, dug their way down to the crates. They dug from the prior night until early the next morning. The legend of the entombed treasure which for a long time gave no peace to the inhabitants of Zamość, now became true.

[Page 752]

And my informant tells me something else: The synagogue itself in Zamość was entirely plundered in one day, when the Jews were driven into the ghetto – in the Neustadt outside of the fortress walls, in that location, where before the war, the Jews had built up an entire residential quarter. The synagogue was so thoroughly plundered, that a single nail didn't remain in the wall.

The skeleton of a huge chandelier still remains in the old synagogue, which the vandals could not carry out. In the attic of the synagogue, are mountains of books, from which the vandals had ripped off the leather bindings… they didn't need the contents of the books, because in such dark days, one cannot make any money from them. Not more, than when the homemakers of the surrounding houses needed a bit of paper for bodily needs, they would send a child up to the attic for a book…

Now, no one will ask, how was it that the Jews of Zamość stood alone during this great misfortune? How was it, that no one in Zamość extended a hand to bestow a word of comfort?

The two Jewish people, who are now in Zamość, are not found in the city proper, but in the new residential quarter outside the walls of the citadel. Zamość is essentially Judenrein. But you will still find a sign, that a seething Jewish life played itself out here, on the external walls of the synagogue. You will find a large painted announcement with Yiddish lettering:

‘Hand workers, merchants and craftsmen! Vote for ballot list number 18!’ –

This was the last rally and the last election for the generations-long Jewish life.

The Jews of Zamość began being slaughtered on the eleventh of April 1942, when the SS murderer Kolb demanded that Garfinkel, the President of the Judenrat, give him three thousand Jews. He provided them. From that time on, each month, ‘evacuations out’ took place, and on October 16, 1942, the Zamość [Jewish] community ceased to exist.

However, by 1947, the Jewish tragedy in Zamość had not yet ended.

In the year 1947, I read over the grave stones on a Zamość street, that were being used as sidewalks: citizens of Zamość step on the headstones of Sarah Torbiner, of Mozhivitzky, Luxembourg, and tens of others, whose names are now difficult to read. The headstones are located on the sidewalk where the house of the previously mentioned Garfinkel stands. The street in front of the circuit court building is also paved with headstones. There, where the measure of justice is taken, The roadbed on the ‘Panienska’ Gasse is paved for two kilometers with Jewish headstones.

On the old Jewish cemetery, the bones from many hundreds of graves have been gathered together, and they were publicly burned. Jewish grandfathers did not avoid the fate of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who were cremated in Belzec, and in Majdanek – also their bones were burned on a wooden pyre.

The fate of the new cemetery was no better. Most of the graves have been disinterred, and one does not know any longer if these are graves or just plain holes in the ground. More than a quarter of the parcel of the new cemetery had been plowed, and planted with potatoes. Just as I was going by, it happened that peasant women had begun to pick the first potatoes from the graves of the Jewish community in Zamość.

The Peretz Library now serves as an office location, and the Bet HaMedrash, where Peretz studied – is a simple residence for a peasant, who has decided to become a cultural statesman.

Editor's Footnote:

By Sholom Stern (Montreal)

The sandy road stretches on to Majdanek. All around is a world of green fields and meadows. Four of us are walking along this road, in the heat of Tammuz. Tow comrades from my hometown, Moshe Krempel, Abraham Eisen, and the teacher, Feivel Freed (who at one time was the editor of the ‘Chelmer Stimme’ and one of my first editors), an intelligent, progressive, Jewish man. He is an educated man, who knows several languages, a great Hasid, and a loyal reader of the Yiddish literature. I remember Feivel Freed from Chelm from before the war: ‘Feivel the Dandy,’ he would be called. The picture of his beautiful wife stands before my eyes. Now, he drags himself along this sandy road. He has aged, gray and knotted up from suffering. He breathes with difficulty. But he does not stop talking. It is his sorrow that is speaking. His wife and daughter were cremated in Majdanek. His wife was led to the gas oven, and his daughter chose to die with her mother, rather than remain alive. So Feivel shuffles along with us, hunches himself, at least it is warm outside, that beats down as if with hot fanned out strands.

Feivel Freed keeps on talking, and emits a continuing stream of imprecations. Whom does Feivel Freed not curse? Everything and everybody. An blasphemy, as if one were hailing bricks down on one's head. After several angry and distant outbreaks, he ends with: ‘I am used to coming here already, to the ‘everyone.’ It doesn't bother me at all, it doesn't bother me, do you hear, my friend Stern!’ His moist eyes glisten at the same time.

The way continues in its sandiness. This is the path of suffering for our people. Day and night, hungry, dumb, wounded, our brothers and sisters were driven to the furnaces. Around electrified fencing, there are watchtowers on all sides. It appears that a fly could not sneak itself out of this place. Along the way – a vigorous scrape with the foot, and the bone of a hand protrudes, a wreckage full of holes, rotting pieces of human clothing. In pits, the bones of Jews, that had been shot, when the Red Army drew near, they shot remnants of Jews in their hurry, and threw them into the pits. Over the pit there stands a hanging scaffold, of the evil beast, the Nazi murderer, the oldest in Majdanek, that the Polish regime seized and hanged. ‘So May They All Be Destroyed!’ The lips murmur in vengeance – but what sort of comfort can there be in vengeance for such an indescribable misfortune!

Not far from the crematoria (one, apparently, the Nazi bandits tried to destroy), workers are sweeping the ash together, which is the residue of two million martyrs, and are erecting a memorial, a mountain of ash from human bones. A horror?! It cannot even be imagined. One's heart falls from pain and shuddering. One wants to run and scream. Yes, howling like some wounded lion in the forest. A mountain of shoes, who had not hear a telling about this mountain of shoes? But when one stands in front of the accumulated mountain of more than eight hundred thousand shoes and tiny shoes from Jews and Jewish children, from a variety of lands, at that time, the earth trembles under one's feet. Many of the little shoes are moldering already. They are being sorted, they are being put out into the sun. When you take a child's shoe in hand, tears rain down on the mold, and it seems as if the warmth of a child's foot can still be felt in its tread. Shoes, shoes, men's, women's, all manner of leather and styles. And the same with clothing, with the numbered camp uniforms, numbered and lettered, everything according to the murderous order, when Nazi German went out to murder and pillage.

Small brushes, small knives, glasses, toothbrushes of all makes. Implements, that Jews took with them from the furthest places, only to be slaughtered in Majdanek. On the walls of one such room, pictures of Jewish children, of fathers, and mothers, from one who was a Rabbi, white, and heavily bearded, with two burning and clear eyes, that cut through the heart. Through the pictures one can experience the tortures of our sisters and brothers, until they were summarily tossed into the gas chambers. Children look like fledglings. They had become so drawn and scrawny from hunger. A girl in her twenties looks like a child. Young people like the old. That is how the wild beasts of fascism tortured our people.

The heat is not tolerable. The sun, by itself, is like a baking oven. However, one stands frozen, one trembles, like a frost has pierced the skin. Rooms open up. The divisions where effects were sorted. The bathing rooms, as the brutes called

[Page 754]

them. From the bathing rooms, a number of steps and the feet go down. One feeling circulates inside, to sink down, to remain lying that way in a gas chamber, and to wail without stopping. But the wellspring of weeping is dried out. Everything is so full of horror. A brutality that in no way can bee grasped with ordinary simple human understanding. You haven't the power to take in this small area of the gas chamber, which can hold a hundred people, and was crammed with 400! From the ceiling, boiling water was poured in, and a hail of a sort of spherical gas [pellet] was rained down like a hail, like little pebbles or peas.

Woe is unto us! Those who died this way, on whom these gas pellets were thrown, died an earlier death. However, they also poisoned with ordinary gas pellets.

The evildoers wanted this to move on expeditiously, but they also wanted to see how Jews writhe in terrible agony. The longer the dying process, the more the Nazi brute derived pleasure. A chimney, holes around the walls, for the gas to escape. The residue of the gas from the pellets remained for more than an hour's time. People became knotted up in each other while standing up, out of pain, they bit their own flesh. From the other side, at a small window, an SS officer sat, observing, how people writhed, and become squeezed against each other, pressed against each other, like a single mass, a single mass of human flesh, which later had to be separated by pouring on water.

Certainly we have read and heard stories about this from the very few, who by a miracle, were saved. However, standing alone in the gas chamber, and the walls begin to glow, even though the chimney is open and cold. All the anxieties about dying emerge, and at the same time, one is seized with such a burning hate for the Nazi and Nazism, that in pain, in the shudder, one swears to fulfill the sacred mission to fight against fascism everywhere, ceaselessly.

All the divisions of this Hell illustrated this human fantasy, however one cannot go through the terror images of Majdanek. The gas chambers, the crematoria, where human bodies were transported and then roasted. In addition, the limestone table with a running spray of water. Like a sacrificial altar, is what this table looks like. Here, people were dissected, if there was even only a suspicion that they had swallowed anything made of gold.

Who can forget the pump, with the water trough around it, in which a Jewish Kapo (I think a murderer from Lemberg), would on each night, grab a Jew by the beard, and turn him with his face down, and hold him in the water, until the Jew would expire. The longer the Jew flailed with his feet, the higher the Nazi murderers would carry on and laugh.

In order to deride the plasterers, they were ordered to engage in sculpture. So people created figurines, like small children, and they were put under a sort of glass. In this ‘art’ there can be found quite a derision, but such evil, that only the mind of a Nazi who gorges himself on human beings can conceive of, in his dark mind.

Majdanek is the fire-Hell of our tragedy. Where, then is the end? Where did this evil beast halt? Nowhere! But the sum total of Majdanek, Oswiecim, Treblinka, can be seen when one visits the cities and towns of Poland, without Jews, without a Jewish soul. Picture this terrifying picture for yourselves, to travel to Lublin and on to Zamość with the bus, and not a single Jew goes by.

It is a quiet, cool early morning. The windows of the tiny peasant huts are still up, and bluish. A peasant woman carries a can of milk, barefoot, with a shawl over her back, she is familiar with loam path. Where is she carrying this milk? To sell it to the Jews? The bus flies along the road. Familiar, Jewish, homey towns swim by: Piusk, Izbica, Krasnystaw, and more and more. In Izbica, walls stare out from the wrecked synagogue. The sun cuts its throat on the shattered window glass. The sun bloodies the morning glow. Former ghetto locations, and camp complexes, and marketplaces. Trading is going on, horses are examined, one sells, one claps ones palms, but not a single Jew.

The towns are so alien and empty. During the day, the sun burned the clouds, and continuously bloodies these sky mountains, until a rain began to flow. The mind burns, as if small spears were lodged there. All the blood vessels are full to the point of bursting. My comrades cover their faces with their hands, so that Poles who are traveling with us,

[Page 755]

will not see their tears. I feel a lack of air. I open the windows, and stick my head out. A rainy wind whips at my line of sight. I feel like a fever is attacking me, I fever from the barren appearance al around, but I do not feel the windy beating impact of the rain on my head. Where are the Jews? Is this a wasteland of a dream? ‘My friends – I want to shout out, – don't cry. It is only an illusion. The Jews have not been done away with, they do not travel to fairs in such heavy rain.’…

It is in this frame of mind that we arrived at Zamość. We went around the small gardens in the four-sided marketplace. The city is intact. The war did not swallow the houses in flame. On all four sides are the usual ‘potchinehs,’ under the stone arches, it is shady. Where my relatives used to live, a crucified Jesus hangs, stained in blood, with a crown of thorns on his head.

At one time, under these shady arches, in the four-sided marketplace with its gardens, it was noisy with Jewish merchants, Jewish wagon drivers from Tyszowce, Komarow, Szczebrzeszyn would come here with stuff to be sold. An intelligent, aggressive Jewish labor youth owned Zamość. Here is the renown Zamość library, and across from it the Municipal Building with its tower clock. Now there is no echo around here. The local residents have appropriated the Jewish houses and stores. The peasants from the area have become the buyers, and simultaneously the sellers to the locals. I continuously think that silhouettes keep flitting by, but no people. How is it possible to take a Zamość like this, and eviscerate it of its Jews? My dreamy young years were surrounded by these very quiet, shady streets and alleys. It is such a suffocating pain, that it isn't even possible to emit a wailing scream. And even if it were possible, for whom to wail? For these local residents, who bathed themselves in Jewish blood, and became rich from our misfortune? But the vengeance will be taken, an accounting is being directed by the new Polish regime against those who carried out pogroms, with those that walk about with a satisfied, cunning little smile and utter: ‘u nac zydków niema’ (We have no Jews').

We don't go, no, we speed, we would have looked and hoped to find a native Jew from Zamość. But suddenly, I begin to think, that I. L. Peretz steps out of an alley, bent over, greyed, his eyes flooded with tears, the pointed edges of his cape flutter, like shadowy vanes on a windmill. He strides alone, and his lips are trembling. The tower clock chimes. The ring fragments itself, just like someone would have flung a brass pan into the number face of the clock. The entire marketplace turns around with me. To where have I been flung? See, I stretch forth my hand, as if I would want to grab the fleeting silhouette going by. See, I mumble, in fright to my friends: Peretz is walking toward the clock tower! Here, he grabbed the iron hands. He hammers on them, and cried plaintively: Where are my Jews? Where is Yohanan Wasser-Treger? Where are the Kabbalists from Laszczow?

My friends pause. They cover their faces with their hands, and weep. And God, once again, brought the sun out from its furry vault… and permitted it to shine down on our heads.

It is market fair day in Zamość. Trade is being conducted behind the wall of the former fortress. We look in on the fair location, and we turn back through the fortress corridor to the Neustadt. It is from here, that the Jews were led off to Belzec to be incinerated. We obtain a photo picture, found on a dead Nazi dog catcher, which shows the Zamość Jews at that place, from which they were driven onto the road to death. Big and small, lined up, a venerable looking old man with a spread out beard, with his bag containing his prayer shawl and phylacteries under his arm, at the head of the community. The picture is so small that we are unable to recognize anyone.

Between the old and the new part of the city, it is as it was. All houses intact, and even slightly more built up and more walls. A new brick road is being laid out along the way. Only one thing – the trip takes too long. We should have been at the cemetery by now, but we are standing at a rather nice park, with stone benches, water is being sprayed on the grass. Children are playing around us. A white-colored cottage stands open, with the sun streaming through it. Where is the sacred place? However, at the horse market, we learn everything already. Faces up, inset head stones lay with the phrase ‘Here is Interred’ with the usual head stone language, which tell of the virtues of those who lie in the ground: a good and honest man….a chaste woman, the daughter of….

[Page 756]

The Nazis plowed under the cemetery, and paved over the muddy spots with the head stones, and lo, a park for play was created. In this manner, even the memory of the sacred congregation of Zamość was caused to disappear. A woman sells flowers, a girl sells ice cream.

We rushed back to the Altstadt, and we learned that there is one Jew in Zamość – the Jewish pharmacist, Epstein. We went into his pharmacy. He finished taking care of a couple of customers, turned over his reading material to a second Jewish man, an assistant of his, who works with him for quite a number of years. The old pharmacist Epstein, was known to be an assimilated Jews, strong-minded. This means, we were dealing with one of the ‘top people’ (read this to mean: ‘real villains of the people’). I there fore understood that he had been a member of the Judenrat. And he immediately confirmed this. To my question: How did you save yourself? He concocted an awesome tale, of how he was in the Judenrat in the beginning, and afterwards, when they demanded that Jews be presented to be taken to their death, he became a ‘righteous convert’…

The bus marks the sand on the roadbed between Zamość and my home town of Tyszowce. I am sunk in my own heavy re-living of the days of I. L .Peretz – the great Jew and poet no longer lies in peace in Warsaw. How could he rest in peace on his bier, among his best friends, Dinensohn and Anski, at the time that they had butchered his brother Jews? I. L. Peretz was tortured with each Jew, individually, on the way to Belzec. He accompanied each contingent of Jews on the way…

It is the evening before Tisha B'Av. The bus whizzes through the outskirts, already over the long bridge, already past the yard, already jostled its way over the second bridge at the beginning of the town, but where is the town? Forthwith, we stop at the second side of town, at the police station. Where did the town disappear to? To where have we traveled? A choking begins in the throat. Thirst burns me, as if I were blundering somewhere in a desert. There is no town.

It had been burned down by the retreating Poles in September 1939. There was a camp in Tyszowce. There is no trace of any house. I cannot find the place where our family house [sic: a legacy] stood. There is no hint of a city, no walls, chimneys, no foundations, only holes and pits covered in thorns, from which black angry ravens caw out at us. Who desolated the town in this way? The Poles, our neighbors for hundreds of years, they sought to pocket the Jewish pittance and plunder it. They, the ones who shot at the retreating soldiers of the Red Army, they who wish to undermine the new Polish regime with vandalism, with the inciting cry in Lublin: ‘Diece nac bogo, give us God!’ It is exactly these, who helped to murder Jews. They were the ones who searched for and sniffed out gold and money from the walls, and in the foundations. They were the ones who ran off with everything, dug up everything, and left behind blind pits, overgrown with prickly wild grass.

The sky is on fire. The sun is a bloody circle that revolves, and from the brick steps, the blood spills out onto the barrenness. The crows rise with frightened cackling; They fly in the burning rays of the sun.

What kind of day is today? Tisha B'Av? But I hear the Friday evening singing of The Song of Songs. But look, here, is where I thing the Husatiner shtibl stood, the Bet HaMedrash, the synagogue with the pictures of the trumpets, the tribes and their standards, the [picture of] the Tabernacle, the wandering Jews in the desert, the Leviathan, that holds his tail in his mouth, because once he takes it out, the world is upended, and returned back to the void. The roof of the heavens at sunset spreads over out heads, and here, it sinks, and the flames ring us about. We walk in a world that screams in flames, and is not consumed. A wasteland! A hot dust whirls about. Black ravens caw, jumping over the pits. An old gentile woman who speaks Yiddish wrings her hands: ‘I don't recognize you, but I knew your parents. Oh, mother! God in Heaven! My husband, my Benedict, do you remember him? The robbers killed him too.’

The Polish town lawyer Jeremczuk and his wife (who as a young girl had lived in Detroit), take us around. He, personally, was in Oswiecim for five years. She tells me about specific details of the slaughter in English. Many Jews lie in the meadows, in the fields. We come to the little river, which led to the pasture. At one time, there was a bathing spot here, and the inn for transients. A wide, running stream meandered between the gardens and the tree stands. Now

[Page 757]

this water is dried out. There is a green swampy blanket on the drain channels. We jump over it. You can see from the drain channels, the blood of the shot and butchered Jews must have flowed quite well. There were two times that the major liquidation slaughters took place: the first, Shavuot 1942 and the second in the last 2 weeks after the High Holy Days. Right here, behind the garden of cabbage and beets, lie the majority of the butchered Jews of Tyszowce, together with Czechoslovakian Jews. Right here, in this toilet hole, they were slaughtered, and after being bayoneted, they were thrown in and covered up with boards.

I tear up a board: shaved bodies, broken forms. I fall on the prickly thorns. Only my lips burn from thirst. The sun makes the Lipowicz Forest look bloody. I think it is the shattered stone from the burned mill. The wheel is on fire. Blood rushes and splatters on the vanes that are slicing. I do not cry, only the pain, like someone was holding a red-hot iron against my darkened eyes. I am blinded.

The wife tells and weeps: ‘I myself was sick. A Jewish girl was being kept with me. She was beautiful and good, like an angel. She came, and pleaded with me to be hidden. But where in this burned out town was there a place to hide anyone? And the local people, the Poles and the Ukrainians were helping the Nazis. That was the greatest horror. Polish neighbors were leading their Jewish neighbors to death. I took my leave of the girl, and as soon as she went out of my house, they began to drag her by her golden locks, and at the haystack, she was stabbed along with her parents, little sisters and brothers. Do you see this little room? Here is where they would cram in the guilty.’

I went out to the meadow. The moon came out and cast its silver light among the ruins. Rows of ravens screeched among the poplars. I thought I would go crazy. I hear all of this, and I remain silent.

I want to cry, but the wellspring of tears has become dry. I want to scream, but the scream cannot come out. It is quiet, it is nighttime in the meadow. From behind the haystack, on the meadow, a young shepherd boy appears, and he plays a sorrowful tune on his flute. The wooden Orthodox Church is old and sunken. The scent of freshly mown hay pervades the meadow. We stride quickly back, it is beginning to grow dark. We go to the orchard in the yard, towards the old cemetery. But we step on gravestones that have been pushed together. Lettering that has been effaced. But here there is a residual line, here and there: ‘The Tale of Two Brethren’ ‘The Deceased Asked that No Words of Praise Be Written About Him,’ ‘Here Lies the Modest and Scholarly.’

The cemetery has been plowed under. There is a garden of all manner of vegetables. A gymnasium has been built there, where the gate was. My grandfather's grave, the gravestone of my parents and my brother was leaned up against an uprooted tree – not a trace remained of that large, sacred location, where according to legend, Moshiach ben Joseph[1] lay interred. For several rows around his grave, Jews would walk in stockinged feet and through notes to the poor tailor, who was a Hidden One. The Nazis plowed up this field. Diluting the living with the dead.

The darkness sinks in around us. In deep pain, I recall, that today is the evening of Tisha B'Av. I cannot, in any way, recall the sorrowful melody of ‘Eykha,’ even though I can picture the Jews in their stockinged feet, on the upturned benches. I am not walking among ruins. Everything has been eradicated. Why do I not scream? We are like the lame. It becomes dark. A heavy darkness covers the wasteland.

The thirst burns. I make my way to the creek. But as I stand ready to pull up the wooden pail, a broad-backed peasant grows up behind me. He grabs the dole, and pours the water back. ‘Before one drinks the water, it is necessary to boil it first. The water is not potable. Once, when there were Jews, there was a pump. Today, there are no Jews, no town, no pump. Death is around. My name is Kalmuk, the police station on the second side belongs to me. You are the son of the zhezhenik (the shokhet's son)?’ Yes, I answer. – ‘Do you know when and how my relatives were killed?’ Well, he scratches and then groans, – Where, you know already yourself. But as to how, that I cannot tell you already. Perhaps it is best that you do not know. See, there, behind the stables, there are also Jews who lie there. With great force, the heads of those who tried to flee into the Lipowicz Forest were split open. Who did this? And if you knew, would it become easier for you?

[Page 758]

I cannot fall asleep… I think that the darkness is swirling about and pours itself over me, like a wave of water. I am drenched in a cold-hot sweat, and tears are pouring from my eyes. The pain is tearing me up, the wellspring of tears has broken open. I bury my head in the straw sack, and I whimper. My companions dream and moan. They whimper in the same way in their dreams. Suddenly, I think it is the Sabbath. Sabbath candle lights twinkle in the town. But the candles don't burn for very long. They extinguish themselves. I try, with my eyes to re-light them in the dark. Let them shine and flicker again through the windows. But I am no longer able to see this image of a Friday night, with lit twinkling Sabbath candles. They have been extinguished. Also the Jews, like burning Sabbath candles, have been extinguished in the midst of life.

On the following morning, with the traveling bus, the barrenness of my home town vanishes. On the thorn-covered mass grave, the silver dew trembles. Once again, the tears force themselves out of my eyes. We know that this is the way they will lie, in the middle of a pasture field, without grave stones. No Jew will ever come back here to mourn them. We are, perhaps, the last, who have the walked their graves in sorrow and pain. We also know, that this which happened to my home town, Tyszowce, Komarow, and Zamość, also happened to all, all of the Jewish cities and towns in Poland.

My entire skeleton is suffused with calamity. I sorrow in anger, I bunch my fists: ‘Remember what the Nazi Amalek did to you!’ Stand up, take revenge in those who annihilated our people, in the evil fascist beasts everywhere!

Translator's Footnote:

|

|

Again, we bring an array of material here from the life and activities of the Zamość survivors in the German D.P. camps. Even after the Holocaust, the years of agony, want and wandering, the sense of community and the readiness to offer help by our Zamość people did not vanish. The simple accounts speak for themselves.

(Account in the periodical ‘Aufgang,’ that appeared in Munich – Yiddish in the Latin alphabet)

On Saturday, December 14, 1946, the first meeting of the Zamość landsleit that had come together, took place in Waldstadt, near Pocking, in the American Zone (of Germany).

In this assembly, 180 landsleit participated.

The assembly was opened by Mr. Naphtali Halpern, who invited 10 landsleit into the Presidium, and greeted the gathering, stressing the need for altruistic assistance.

The floor is given to Mr. Jekuthiel Zwillich, who in short words relays the history of the tragic destruction of Zamość Jewry. The Cantor, Appelweiss intones a memorial for the martyrs of Zamość. The memorial is accompanied by weeping from all the attendees.

After the memorial, the floor is given to Mr. Moshe Garfinkel, the member of the organizing committee, and vice-president of the camp leadership, who also intones about the necessity of organizing all of the landsleit in the American Zone; about continuous contact with the brothers in North America, the Land of Israel and other countries.

A committee of the following is elected:

Chairman:Moshe Garfinkel– Waldstadt;