|

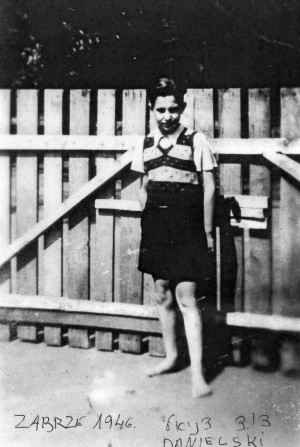

at the orphanage in Zabrze in 1946

|

|

[Page 55]

The Children of Zabrze

Translated from Hebrew by William Leibner

Edited by Phyllis Oster

|

|

| David Danieli, formerly Daniel Danielski, at the orphanage in Zabrze in 1946 |

David Danielski (surname later changed to Danieli) was born in 1932 in the hamlet of Pszczyna. His father, Max or Maximilian, was a pastry baker. The family soon moved to the bigger township of Rybnik in Silesia where Max opened a bakery in the center of the city. The bakery was very successful and the family flourished. They had a maid and their apartment was well furnished including a piano, and many antiques which David's mother, Hannah, collected. David's older brother Sasha had died in 1928 so the younger boy received a great deal of attention from Max and Hannah. But his parents insisted that David be independent and able to defend himself when the need arose.

David does not remember much about the family or their friends. He does remember playing with other children in the courtyard of their apartment building. The family was not very religious although they belonged to the Jewish Community Center. He recalls attending very crowded services on a few occasions at the main synagogue, and his mother giving him a flag crowned with an apple to take with him to synagogue in celebration of Simchat Torah.

The new order in Germany appointed a German supervisor over the bakery, who was in essence the owner. Max Danielski was permitted to stay on at the bakery but only as a worker. Then the family was forced to move to a poorer section of the town, where other Jews were also forced to live. The new flat consisted of one room into which everything possible was moved. David's mother started to sell items from their home to provide food for the family since her husband's income became smaller with time. While selling her household items, Hannah Danielski met a German Silesian woman, Martha Kapitza, who was also involved in buying and selling goods. The transactions were highly illegal, but Hannah was able to trade her valuables for food.

Max learned from a friendly policeman that anti–Jewish actions were being planned and started to make arrangements for his son's disappearance. He contacted a Polish farmer who lived in Babia Gora and was willing to take David for a time. Hannah packed a small suitcase, gave him some pocket money and bought him a train ticket. He traveled alone to the farm. He remained with the farmer and his family for some time helping with various farm chores. On a cold night in February of 1942 the farmer took David to the station and sent him home to Rybnik. He headed home and found the apartment dark with no lights in the window. The Gestapo had posted an order on the door forbidding admittance to the premises. He had no idea what had happened to his parents and did not know what to do next having no other family in the city.

David decided to cross the street and approach the neighbor, Martha Kapitza, who had become friendly with his mother. She offered him a place to stay until things settled down. Through her David learned that all the Jews of Rybnik including his parents were rounded up and shipped to an unknown destination. Nobody knew what happened to them. He snuck into his parents' flat through a window and found that the police had ransacked the place and made a shambles. He made two trips to his former home, carrying away as much as he could and never returned. .

Anton Kapitza, the husband of Martha Kapitza, was an out of work, disabled coal miner of Polish Silesian origin. Martha was a native of Zabrze or Hindenburg, and provided for her family by selling luxury goods in exchange for food which she then resold. The market for these goods was excellent since there was a scarcity of finer goods in Germany during the war years. Hannah Danielski traded regularly with Martha Kapitza before she was deported and they had become good friends. Mrs. Kapitza had five children: Elizabeth who was a mute; Ernest, a soldier; Gertrude who delivered papers; Ludwig who worked in the building trades and was a bit slow; and the youngest Zigmund, born in 1933. David and Zigmund were close in age and got along pretty well. Gertrude, the oldest, born in 1923, assisted her mother in running the house and contributed financially. David did chores and errands at the direction of Martha or Gertrude Kapitza and adjusted to the situation as best he could. He knew that he was Jewish but that was about all he knew about Judaism.

Time went by and suddenly the Gestapo started searching and questioning people in the area. Apparently, someone either reported David or he heard the authorities were looking for him. Mrs. Kapitza packed a few items of clothing, gave him some money and the address of a farm supervisor in Striegau, Germany, who was originally a Polish police official. David left the house and headed for the train station just before the Gestapo arrived at the Kapitza home asking questions about his whereabouts. Gertrude later told him that her mother stated that he had left the house after stealing money. Mrs. Kapitza was even questioned at headquarters about the case but eventually the matter was dropped since she insisted that she had no knowledge of his whereabouts. Gertrude also revealed to him that her mother had promised Mrs. Danielski to help protect her son.

Meanwhile David remained with the farm supervisor helping with the chores. He started school, immediately proceeded to third grade and joined the “Hitler Jugend” or Hitler Youth, as every child belonged to the organization. He remembers collecting all kinds of materials for the war effort. One day, on the way to school, he saw for the first time people in striped pajamas who were inmates of the Gross Rosen concentration camp. He was reminded of his Jewish heritage and very worried about his parents. He would find out later that Mrs. Kapitza sent food to the Danielski's with a German who had worked with Max near Rybnik. Max died about June 16, 1942 and Mrs. Danielski was killed in Auschwitz in December 1943 at the age of 43.

By June 1942 David had returned to the Kapitza household and taken over the newspaper route since Gertrude had married and left the house. Mrs. Kapitza managed to obtain a baptismal certificate for David and he began to attend school. He was frequently late due to the newspaper deliveries that steadily declined as the war went against Germany. Conditions in Germany worsened by the day although there was still enough food. The school building was soon converted into a military installation and classes ceased. The Russians were advancing on Germany. Being sent to the Eastern front was considered a death sentence. The Russians reached Rybnik in the winter of 1945, where they expelled the entire German population. The Kapitza family made the 40 mile trek to Zabrze where Martha's sister lived. Then the hardships really began. Anton Kapitza and David decided to head back to Rybnik and found the Kapitza home ransacked. The Russians had cleaned the place out including the basement where some food was well hidden.

Conditions were very bad The family made cookies and sold them to buy food. While dealing in the Rybnik market, David was approached by a Jewish man, Mr. Gold, who asked if he was Jewish and offered to help him return to Judaism. David felt an obligation to talk to Anton Kapitza first who saw no problem in David's learning about Judaism, Mr. Gold, who resided in Bytom, invited David to live in his home. Gold was in the process of preparing to take his family to America and asked David to join them. He agreed.

Gold also told David about the orphanage in Zabrze where he could learn about Judaism. David was sent to the orphanage, where the head teacher, David Hubel, had a great impression on him. David became an ardent Zionist, and was no longer interested in emigrating to the United States. Instead David wanted to go to Palestine, and became very active in Zionist activities at the orphanage. The Gold family was disappointed by the decision since they really wanted to take David to the United States. They parted and never met again.

David enjoyed his stay at the orphanage where he learned the basic tenets of Judaism, Jewish history and the Hebrew language. He also attended the regular Polish school in accordance with Polish educational requirements. But David really did not devote himself to those studies since he wanted to go to Palestine. Then rumors started in the orphanage that Rabbi Herzog was coming to take all the children to Palestine.

Rabbi Itzhak Eisik Halevi Herzog, chief rabbi of the British Mandate of Palestine, received a promise from the British administration in Palestine to give entrance certificates to 500 Jewish orphans who had survived the war in Poland in monasteries, Christian homes, forests and caves. There was great excitement at the Zabrze Jewish orphanage on Karlowica Street Number 10, Zabrze, Upper Silesia, Poland, with the news of imminent departure for Palestine. Rumors chased rumors but then the children were ordered to pack. Every child began to pack their few belongings; some had smaller, others bigger suitcases. The Zabrze contingent consisted of complete orphans, partial orphans, children with one parent, children with one parent aboard the transport, and children who had returned from Russia.

The following is a list of some of the Zabrze children that David Danielski could remember. In some instances the children were known merely by their nicknames.

Shlomo Korn

Tzvi Shpigler

Shlomo Shpigler

Yehuda Tzvi Sobol

Riwka Brender

Tzvi Brender

Yeizik Peitznik

David Fridman

Hannah Hoffman

Rivka Motil

Fela Kozoch

Sonia Mayer

Heniek Mayer

Arieh

Charlotka. Brother and sister

Yehudit Wilczenski

Mrs. Wilczenski

Renka

Her sister

And mother

Naomi Agrabska

Esther Kastenberg

Emil and mother

Big Eva

Ella

Roma

Dwora Ditman

Shmulek

Batia Sheinfeld

David Danieli

Raya, the group leader

Some children remained at the Zabrze home with a staff headed by principal Dr. Nehema Geler and head teacher David Hubel.

David left the Zabrze home on Thursday afternoon the 22nd of August 1946. The Zabrze group first headed by tramway to the nearby town of Katowice where a train was standing on a sideline with hundreds of children, group leaders and teachers. They came from many orphanages in Poland: Lodz, Krakow, Warsaw and Katowice. The greetings, shouts and tears were beyond description. Order was soon established and the Zabrze group boarded its assigned car. Captain Yeshayahu Drucker, dressed in his military uniform, was there as was Rabbi Aaron Becker. Both military chaplains had their hands full with all the logistical problems. Soon, the Chief Rabbi of Mandate Palestine, Rabbi Itzhak Eisik Halevy Herzog and his son Yaakov Herzog arrived and boarded the train. They came specifically to escort the train out of Poland. Late that evening, the Herzog transport of children started to roll in a westerly direction toward the Czech border. The trip was slow moving and frequent stops occurred, especially on the border between Poland and Czechoslovakia. Rabbi Drucker and Rabbi Becker said goodbye to the children and headed back to Warsaw to report to the Chief Military Chaplain of the Polish Army Rabbi David Kahane. A day later, on the afternoon of August 23, 1946, the train crossed the border and arrived at a big industrial Czech town, Moravska Ostrava. Arrangements were made for lodging and feeding the children and Rabbi Herzog's entourage at a local hotel, the “Moravska,” where they stayed until Sunday when the trip continued to Prague.

The situation at the hotel was quite chaotic until each child was assigned a room and Shabbat set in. The transport included religious youth from Hapoel Hamizrahi and Agudath Israel, who tended to religious services presided over by Rabbi Herzog. The hotel was nicely furnished and included such novelties as elevators, telephones and venetian blinds which were all a great source of entertainment for the children. .

On arriving in Prague, the children disembarked and were taken to the Repatrianski Tabor Dablice refugee camp located in the northern part of the city. The camp was huge, with Jews from many different places, and absorbed the transport easily. It is unclear why the children were taken to the camp, but they remained there for five weeks. His stay in the camp had a great impact on David, both because he was immersed in Judaism, and had the opportunity to learn about Prague, which he came to love. To keep the children busy, city tours and lectures were organized. Most of the children were exposed for the first time to the wonders of an important cultural metropolis.

The High Holidays arrived and on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, the children walked from the camp to the Maharal synagogue, better known as the “Alte Neu Shul.” There David heard the story of the “Golem” for the first time. He was very impressed with Prague, its streets, its bridges and squares. The Charles Bridge with the huge cross and the Hebrew words “Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh!” (Holy) written on it particularly caught his attention. Here was a city that respected Jewish letters in Europe.

With the end of Rosh Hashanah, the children boarded a train headed south to Bratislava along the Danube River, crossing the German border near Munich, Bavaria, then continuing west across the Rhine River to Strasbourg, France. Here for all practical purposes ended the Herzog transport of children. Despite all efforts, the British refused to grant entrance certificates to the children. Rabbi Herzog was aware of the situation but could do little except make arrangements for each political group to care for its contingent in the transport. At the beginning of their journey in Katowice, the Zabrze contingent had been absorbed into the Lodz and Krakow group under the auspices of the Hapoel Hamizrahi movement, a moderate religious Zionist group.

On arrival in Strasburg, the Bnei Akiva youth organization, part of the Hapoel Hamizrahi movement, welcomed the children and saw to their needs. Their actual host was the well to do Bloch family who first lodged the children at the university and within a few days moved them to a large home at 23 Rue de Selenic in a nice residential neighborhood. The house was big but not large enough to comfortably accommodate the group of about 250 people, including children, parents and staff. The noise, the commotion and constant activities soon attracted the attention of neighbors who began to refer to the house as “ la maison de fous” or crazy house. It quickly became a problem and the Bloch family moved the smaller children to a large estate in Schirmeck with plenty of land. The Schirmeck home was headed by Mr. Spiner, who came from Krakow. The older children lived at a home in Strasburg run by Meir Weissblum with whom David still maintains contact.

The older youth were anxious to leave for Palestine and became frustrated. Soon a group of about17 youngsters formed a small unit that worked to secure passage. David was chosen to write a letter to David Hubel asking his help. The letter worked and the group was told to leave for Marseilles, one of the assembly points for illegal immigration to Palestine. The group left Strasburg in March 1947 and shortly thereafter boarded the illegal refugee ship named “Exit Europe 1947” better known as the “Exodus ship”.

The story of the passengers experience on the Exodus is well known. David still vividly remembers the Rosh Hashanah that he celebrated on a British detention ship in the port of Gibraltar on the way to a detention camp in the British sector of Germany. He quickly left the British detention camp and began to move in the direction of France. Luckily he was able to cross the border to France and rejoin the orphanage that he had left earlier that year. The home was now closed but the orphanage had moved to the castle named “Chateau Raye” in the village of Le Vauson near Paris.

Then the State of Israel was proclaimed in 1948. After having left Zabrze, Poland on August 22, 1946, David, and other Herzog transport youngsters arrived at the port of Haifa on August 16, 1948.

David is presently retired and has made several trips to Zabrze where he met Gertrude Kapitza, the only surviving member of the Kapitza family.

|

|

The above picture was provided by the museum of “Lochamei Hagetaot”. |

I, Shlomo Koren was born in Nowy Sacz, Galicia, Poland and survived World War II in Russia, returning to Poland following the war in 1946. My family settled in Katowice, Poland, where I was registered in a city public school but did not attend classes. I barely spoke Polish. I met David Danieli (Danielski) in Katowice. He told me that he was attending a Jewish school in Zabrze, about a half hour away, and invited me to visit him. I visited the Zabrze home on several occasions and was pleased by the ambience of the place. I liked the home, especially the individual attention that the place gave the children. I discussed the situation with my mother and sisters. I had no father. The family had difficulty controlling me and I often roamed the streets of Katowice, so they consented to my moving to the home. The orphanage readily accepted me, for the institution was specifically created for children like me.

At Zabrze, I was in a room with two other boys; one of them named Morin Landau. Each of us had experienced horrible events that we tried to forget. Some of the girls at the home spoke only Polish and continued to pray and cross themselves, refusing to admit that they were Jewish. The teachers and supervisors had a difficult time reaching some of the children but with time managed to win their confidence and provide them with a basic education and a bit of self–confidence. Jewish religious education was introduced in moderation so as not to antagonize the children who were ill at ease if not hostile to anything Jewish. The boys were taught how to pray, put on phylacteries, the girls were taught about lighting candles and all children were exposed to Jewish holidays and a bit of a Jewish atmosphere. Hebrew, Jewish history, and Zionism were stressed at the home.

Within the compound of the Jewish community at Zabrze near the orphanage, there was also a building where a group of young pioneers were preparing themselves to move to Palestine and work the land. The group or kibbutz belonged to the Ichud Zionist movement. We watched the youngsters frequently dancing “horas” and other folk dances in the yard of the compound and were impressed. Their enthusiasm inspired us to become more fervent Zionists. After four months of ideal life at the home, we heard that Rabbi Herzog was coming to take us to Palestine. I began to beg my mother and sisters to permit me to leave Poland with the others. They were not opposed to Palestine but feared the distance and the unknown. Slowly and persistently I managed to convince them that I must go to Palestine. Mother bought me a new jacket, shoes and stitched some dollars into my pants in case of an emergency.

Time flew and we left the home and headed to Katowice, Poland, where we boarded a train with other youngsters. The train waited for the arrival of Rabbi Herzog and his entourage. He arrived late in the evening and the train started to roll to the Czech border. The next day was Friday, the train stopped and we spent Shabbat at a hotel in Moravski–Ostrava. There was a bit of chaos at the hotel since the children made great use of the hotel telephones, elevators and borrowed items that were never returned.

On Sunday the train resumed the journey to Prague where we disembarked and were taken to a refugee camp named Repatrianski Tabor Dablice to await entrance visas to France. We would remain in this camp for about six weeks. Our Zabrze group became part of the Hapoel Hamizrahi group. The group leaders were not well disposed to our Zabrze contingent since we spoke primarily Polish and were less familiar with Jewish customs than the Mizrahi group. A certain distance existed between the groups. The Zabrze group was very sensitive and received a great deal of attention at the home due to our origins and experiences while the regular Mizrahi youths were familiar with Jewish life. The Mizrahi youth leaders also lacked the necessary educational tools to handle the sensitive Zabrze contingent. Still, a routine was established at the refugee camp and we youngsters had to abide by it.

Some of us boys, including David Danieli, soon formed a group that would travel to Prague and spend time in the city. I sold my stamp collection in Prague in order to have spending money. We went to the movies and saw many city attractions in Prague. I was displeased with our group leader and joined a group of boys that raided the youth warehouse following dinner on the first night of Rosh Hashanah. We took clothing and food and gave it all out to the children, who appeared at services the next day at in brand new outfits. The group leaders could do little about our antics.

The French visas arrived a day after Rosh Hashanah. We headed to the railway station, boarded a train and traveled for the next two days across Germany until we reached Strasbourg, France. We were taken to the Strasbourg Jewish community service center, where we spent the holidays. We were then moved to a three–story house on Rue Selenic in the center of Strasbourg that belonged to the Jewish community. The main floor had halls that were converted into a synagogue, dining room and study centers. The second floor consisted of dorms and the third floor had small rooms for the staffers and their families. The place was crowded and disorganized. The group leaders became a bit more tyrannical in their behavior toward us. Discipline was strictly enforced and offenders were given cleaning chores as punishment. Soon the younger children were removed to a home in Schirmeck, making life at the home a bit easier.

Some of us were not pleased with the management at the home and expressed it openly. The administration then made arrangements to move nine of us to the Jewish orphanage of Strasbourg administered by Mr. and Mrs. Blum. The Blum's gave us a warm reception with plenty of tasty food, some clothing, bed sheets and transportation passes. We were assigned to an American ORT program where we were taught various trades. I selected courses in metal work. The instruction was primarily in German but I also received instruction in French. All children had to attend services at the synagogue of Rabbi Deutch of Strasbourg.

I had ample time to enjoy the city and meet with my friends who remained at the home in Rue Selenic. But I was restless and anxious to head to Palestine. I started to talk to the other boys of the transport and we soon formed a group that was determined to make aliyah. We approached the children from the home on Selenic with our plan and some youngsters joined us, including David Danieli. We had neither the money nor the connections to carry out our plan. David decided to write a letter to his friend, David Hubel, the headmaster in Zabrze, explaining our problem and asking for help.

The answer soon came in the form of train tickets and a date of departure to Marseilles, France. We packed and bid farewell to our temporary homes. The Selenic Street home threw a party in our honor and we left for Marseilles where an emissary met us and took us to an isolated and empty house. We remained there until Passover and then moved to another camp facing the sea. Here preparations were being made for the departure of the next illegal ship. Hundreds of boarding passes were forged with the South American country of Columbia as the destination. Then one night, Jewish refugees began to arrive en masse and were organized in groups and sent to board the Exodus ship. Our group was one of the last to board the very crowded ship.

On July 11, 1947, the ship managed to leave the docking berth without a pilot and headed out to sea. The British navy followed the ship and then rammed the boat on the high seas. Fights ensued between the British boarding parties and the immigrants resulting in the death of three civilians, among them an American sailor, and dozens of seriously wounded passengers. The illegal ship was brought to Haifa where all passengers were transferred to three prison ships and started their voyage back to France.

The French refused to force the passengers off the boats and eventually the ships sailed to Hamburg where we docked on September 6, 1947. Our ship, the “Empire Rival”, was the last ship to dock and we were immediately placed aboard a train and transported to Lubeck where trucks took us to the camp called Amstau. We were later transferred to another camp named Pependorf where there were more youngsters. Here we participated in various activities and also studied Hebrew. Soon we began to travel in the direction of France under the leadership of “Bricha” agents and eventually made it back to Strasbourg. The home at Rue Selenic was closed and Mr. Blum was happy to see the group. I continued my train trip to Marseilles where I entered a huge refugee camp named “Grand Arnas.”

|

|

| Numbered certificate issued to the passengers of the famous “Exodus” ship. |

The camp contained many nationalities including Jews waiting for visas for America or residence papers to stay in France. Within a week we were transferred to the Jewish Agency camp “Villa Gabi,” a beautiful place overlooking the sea. Here we awaited an illegal ship that would take us to Palestine. Then came the order that only volunteers for the Israeli Army would be sent to Israel. I was informed that I would be sent back to the Rue Selenic orphanage that had now moved to the Chateau Voisin near Paris. I refused to go back to the home and joined a Hagana training camp in the vicinity of Marseilles. I lied about my age, told them I was 18 and was accepted for military training. I then boarded a ship with Canadian volunteers and landed in Haifa toward the end of May 1948. I was immediately sent to the “Yona” military base near Beit Lid and within a few days, I was ordered to assemble with the other soldiers. I must have looked younger than the other soldiers because when the commander saw me, he told me to return my weapon and wait for him. Following the formation, he dropped me off at the immigrant hostel in Raanana on his way to visit his parents. Thus ended my wanderings from 1939 to 1948.

|

|

She has graciously written her life story for us. |

I, Batia Akselrad Eisenstein, was born on May 5, 1932, in Krosno, Galicia, Poland. My parents were Bendet and Cila (nee Freifeld) Akselrad. My father owned a sawmill and was the head of the Jewish communities of Korczyna and Krosno. I had five older brothers. The oldest Shmuel, was born in 1909, married to Klara Rosenberg from Debice and had a daughter named Irenka, born in 1935. My second brother was Shalom, born in 1911, followed by Avraham in 1922, Yehuda in 1924 and Levy in 1930.

|

|

| Bendet Akselrad |

|

|

| Cila Freifeld–Akselrad |

My family revolved about my father who was devoted to the Jewish community. He was a gentle person who had a great deal of patience and listened to everybody who came to the house with a problem and the Jews of Krosno and Korczyna had many problems, mainly survival problems, in a sea of anti–Semitism. To this day, people who knew my father praise him for his patience, understanding and assistance in solving problems. These people describe to me in great detail his deeds that were unknown to me at the time, and make me feel proud of my parents and family.

As a child I loved the Jewish holidays of Purim, Passover and Friday nights. My father always brought home dinner guests from the synagogue who joined us at the table and shared our meals. Dinners were always interlaced with conversations and discussions. Father devoted most of his time to the community and considered this task to be his “'raison d'etre” or essence of life. Mother also helped my father since she received the people who came to the house while father was not at home. She spoke to the visitors and made notes that were relayed to father on his arrival. My brother and I also had important jobs for we ran to open the door whenever the bell rang. Many of the family discussions revolved around the impending war and my parents and older brothers were very perturbed by the news events of the day. I was terrified and expected the worst, especially when I heard the rantings of Hitler on the radio. I had bad feelings but did not really understand what was happening

Many influential Polish gentiles visited our home and discussed ways and means to avoid or smooth sore spots within the Krosno community among Jews and Christians. The Polish population was very anti–Semitic and the slightest incident could turn into a major riot or a pogrom as often happened in the country. The Jews wanted to avoid confrontations at any cost and merely desired to continue with their lives.

My father left his various businesses in Krosno to his older sons while he devoted himself to the needs of the Jewish population. Shmuel and Shalom graduated from the school of commerce and administration, where my father had also graduated. Schooling was very limited to Jews and some trades or professions were closed to Jewish students. In some instances a few Jewish students were admitted as tokens. Even gifted Jewish youth could only dream about positions or jobs in governmental or public offices.

The Polish–German war started in September 1939 and my brother Shalom was immediately drafted at night and I was unable to say goodbye to him. Time passed and we heard nothing from Shalom. Then a Pole came to our house and told the family that my brother was seriously injured and being treated at a hospital in Stanislawow, Eastern Galicia. Of course, he received a nice reward for the information. My father, Avraham and Yehuda, went to Stanislawow where Shalom was supposedly convalescing. They soon discovered the whole thing was a hoax. Shalom was not there. They did meet many Jews from Krosno who had fled to this area prior to the arrival of the Germans. My father and brothers had a difficult time returning home because Russian forces now occupied Stanislawow as part of the partition of Poland by Germany and Russia. When they managed to reach Krosno, a post card was waiting from Shalom saying he was a prisoner of war in a German camp. Shalom continued to send post cards and in one of them he let us know that he would soon be sent home. Our joy was boundless.

By then father was very busy with the community, assisted by his elder sons. The city of Krosno had received Jewish refugees from many places who needed help and temporary lodgings. The Jewish economic situation in the city was very bad, many Jewish businesses were confiscated and Jews were not permitted to circulate freely in the city. Each day was worse, a white armband with a Star of David had to be worn, new anti–Jewish rules and regulations appeared regularly. The situation assumed alarming proportions and my father and brothers barely coped with the situation and found it difficult to provide all the help needed.

The fact that father and my brothers spoke German fluently –– since the family had lived for many years in Vienna and had Austrian citizenship ––gave them the ability to use the language to help the Jews of Krosno. The Germans refused to deal with Jews and especially those who did not speak German. Every demand had to be written and submitted to the Germans in their language. Requests were constantly drafted on behalf of the Jews of Krosno. Then each had to be followed up. These missions were mostly met with negative answers which reflected on my father's face when he returned home. Although I was small, I began to hear strange and meaningless but frightening words like concentration camps, ghetto, searches and Gestapo. I did not understand these words but feared them for they were uttered in fright. I began to mature rapidly as children do in such special circumstances.

One evening father came home and I saw the sadness in his eyes. Mother told me that they wanted to talk to me privately. Father told me that he had found a special place for me with a fine Polish family that wanted me to live with them. He told me that this family would like me very much. I listened seriously but did not really understand what was taking place. Mother packed a bag with clothing. The next evening, my brother Shalom took me to the home of the Krukierek family. We were well acquainted with the Krukierek's because the sons worked at our sawmill in Krosno.

During the walk he explained to me how to behave in the new home and to be a good and obedient girl. He instructed me to listen and fulfill all the commands of the new family. He also told me that I now had a new name that I must use. Furthermore, he said, I must not cry or ask to return home, my family would visit when they could. Parting was very sad, I saw the tears in my brother's eyes and I barely restrained myself from crying.

The Krukierak family consisted of the grandmother, Weronika, the grandfather, their married daughter Jozefa and her husband. The new family named me Basia (a typical Polish Christian name). I cried the entire first night and was unable to fall asleep. I had a hard time adjusting to the idea that I was left alone with a new and strange family. No longer would I be able to rejoin my dear and beloved family. I rose early in the morning and went to the yard. I approached the gate and looked at the path that we used the previous night, but nobody was in sight.

I stood there and cried, hoping to see a familiar face, but no one appeared. I stayed there for hours each day in the hope of seeing someone from the family, but in vain. I was depressed and entered the home only when grandfather called me to eat, but I had no appetite. Grandmother understood the situation and tried to alleviate my fears by saying that my old family would probably visit me soon. This of course did not help but it did show me that someone cared. Needless to say, I was very happy when a member of the family visited and brought a gift from my old home. They made promises to visit often to cheer me up, for they saw my red and swollen eyes. They all did try to visit often except my brother Avraham. One day he went to buy bread and had disappeared. Our visits always ended in sadness for I was left alone again.

These visits continued and then suddenly stopped. At that point I was 11 years old. Although I didn't know it then, in one year most of my family was taken and murdered by the Nazis. My mother Cila Akselrad was caught and shot in 1943 in Korczyna. My father Bendet Akselrad was shot on July 15, 1943, in the concentration camp of Szebnie. My brother Shmuel, his wife Clara, their daughter Irenka, and Shalom Akselrad were caught in Warsaw with false Aryan papers and killed. My brother Yehuda joined the partisans and fought with them until 1943 when he was killed in the vicinity of Warsaw. My brother Levy was killed in Krosno in 1943. Only Avraham Akselrad survived the concentration camps and managed to reach New York where he passed away in 1991 after a lengthy illness. He never married. Thus, I was the sole survivor of the family in Krosno and continued to live with the Polish family.

I missed my parents and brothers and kept dreaming about them. I saw them almost every night in my dreams and was very happy, only to awaken to the bitter reality that I was alone. I remained in the house with grandfather and grandmother, while the couple went to work, and helped in the house with everything that I could since I was always afraid that I might be kicked out. This fear lingered on and frequently prevented me from sleeping. I slowly became attached to the new family and became more familiar with them. They worried about me and were constantly fearful that an informer might reveal my existence to the Germans. The home of the new family was located in a rural area in the vicinity of the airport of Krosno. Still there was fear that someone might spot this young girl in the courtyard. The Krukierek family decided that the risks of being exposed were serious and began to shift my hiding places. Sometimes I slept hidden in a straw bed in the attic. Others times I was hidden in dark places that affected my vision on seeing light.

On nice evenings, I would emerge and play a bit in the wheat field. Some evenings, grandmother would give me a basket and send me to pick potatoes. I dug the potatoes by hand in the dark so that no one would see me. I picked the big ones and left the small ones in the ground so that they would continue to grow, as grandmother Weronika instructed me to do. I would return with a basket full of potatoes and then clean them before entering the kitchen. I spent a lot of time peeling potatoes, and was very busy doing household chores, for grandfather had a leg injury and limped, and grandmother was weak and tired easily. When Grandfather was pleased with the work, he would say that I had earned my keep for the day and give me an extra heavy slice of bread. Grandfather was rather economical with his compliments; thus I relished them when I received one.

Potatoes and cabbage was the standard food for the family. Sunday was a special meal that consisted of potatoes, cabbage and rabbit meat. The rabbits were raised on the farm next to the cows and roosters. At night I picked potatoes and during the day I tended to the daily house chores. I did all the chores with devotion for I craved attention and very much wanted to be accepted.

In addition to the regular house chores, I also mended clothing, helped prepare the feed for the cows and did many other kinds of work in the house. Of course, there was less work during the winter when the weather was freezing and the fields were covered with snow. I spent my time hiding in the cowshed, talking to the rabbits and roosters. It seemed to me that they answered but I was not sure if I heard them. I was very lonely and continued to talk to the small animals for I had no friends.

This was a difficult period, for the Germans increased the intensity of their searches. My adopted family was seriously frightened and even considered throwing me out. I was terrified and could not fall asleep for fear of winding up in the street. Grandmother cared a great deal for me and told the others she would assume full responsibility for my protection. She also said that she would leave the house if I were thrown out. Grandmother's threats worked and she saved me. She then asked her son Kazek to hide me at the mill where he was a guard. The sawmill had belonged to our family prior to the war, but was now owned by a German named Schmidt, and Kazek watched the place. He built a hiding place and one night took me from the house in a bag of sawdust.

The hiding place was under a wooden floor amid sawdust. Kazek's brothers also worked at the mill. Kazek brought me to the hiding place and gave me instructions on how to behave during the day when the Polish workers tended to their jobs. He also showed me how to position myself in the hiding place so as not to arouse suspicion. I could not sit, move or turn in the dark hiding place. During the day it was still bearable but at night it was frightening. I kept dreaming about my parents and brothers. I had the premonition that they were all killed. I did not want to dream but could not help myself. Rats occasionally ran over my body and I could not stop them because there was no room to move my hands. It was horrible.

For several months I continued to sleep in sawdust under the wooden floor. Autumn was approaching and with it came the rains. Everything was cold, wet and dreary. Still I had to stay in hiding during the day for fear of being spotted by a worker or by a customer who came to buy wood. Only at night could I slowly venture out. As a result of my hiding position, I could barely walk. I was depressed and often thought of ending my life, but I was a coward. I did not divulge these thoughts to Kazek for fear of embarrassing him after all his efforts on my behalf.

Winter approached and the family decided to return me to the house. They still hid me but within the house for it was bitter cold outside. I also became accustomed to Catholic traditions and realized then that I would never return to Judaism. I no longer wanted to belong to the persecuted and humiliated Jewish people. Grandfather often told me that the Jewish people had been persecuted throughout history. Even the Arabs were killing Jews in Palestine. I heard and saw all these things. I saw how Jews were being persecuted while the Christian children played and had fun. I felt jealous and felt ashamed at having been born a Jew.

These thoughts persisted and became stronger as time passed. Suddenly, the roar of shells shook the entire area for we were near the Krosno airport. The Russians shelled the entire area prior to their advance and for several days the cannon fire could be heard and then silence. The area was liberated but nobody came to take me home. I started school for the first time in 1945 and was registered as a Christian student. I excelled in my studies since I devoted myself wholeheartedly to schoolwork. I was a very good student and easily made friends. I felt a certain compensation for all the years spent in terrible deprivation. I also decided to convert to Catholicism; which pleased the family and gave me further security at home.

I went to the priest in Krosno and asked to be baptized. He was very surprised and told me that he knew my father. He asked whether there were any survivors in the family and I replied that I was the sole survivor. The priest baptized me on September 5, 1945, and the same month I started school for the first time. I was admitted to the seventh grade in the elementary school for which I was prepared by a private teacher since I had to make up a great deal of schooling. I was a very diligent student and loved to go to school and to study. I made many friends and wanted to be accepted. I tried to make up for all the lost time that I was locked up. I finished elementary school and received a certificate. I was registered to continue schooling the next year and meanwhile I enjoyed the summer recess during which time I met my friends and took trips with them.

My brother Avraham Akselrad had survived the camps and slowly recovered from his poor medical condition. He returned to Krosno and came to the Krukierek family to look for me. Avraham tried to take me away from the Krukierek family but saw that he was getting nowhere and was too weak to fight. He spoke to me about traveling to the Jewish orphanage in Zabrze but I refused. I was determined to stay with the family. I even refused to talk to him. I left the house and hid in the bushes until I was certain that he had left the house. Then I returned home and was furious at my brother for trying to separate me from my new family. He decided to seek legal redress and contacted the office of Rabbi Kahane to plead for help. Yeshayahu Drucker was assigned to the case. Drucker took the case to court since I was a minor. The court heard the case and forced me to stay with my brother at the orphanage in Zabrze for a period of two weeks. The family presented a huge bill of expenses for my upkeep during the war years. The bill had to be paid to the court as a deposit in case I did not return to the family. My brother did not have the necessary cash but he assigned his share of the family property to the Krukierek family if I did not return to their house. My share was untouched since I was a minor. Then the court began to implement the decision.

I was very homesick and wrote letters to my adoptive family but never received a reply. They evidently wrote to me but I never received the letters. The orphanage knew that my adopted Polish family could kidnap me, so the Zabrze home stopped all my correspondence. Shortly thereafter, I was sent to France with a transport of Polish Jewish children. I remained in Perigueux, France, for two years and then I went to Israel in 1948. I was sent to the agricultural school “Mikveh Israel” and in 1950 joined the army. By 1953 I had married and was raising a family, including two sons and 4 grandchildren. I live in a private home at Kiriat Ono and spend my time tending to my garden, attending lectures and reading books.

I continued to write to the Krukierek family after I went to Israel. Jozefa Krukierek, the woman that kept me hidden during the war years, died in 2002 at the age of 92. I even maintain correspondence with the grandchildren and the great grandchildren of the family who never met me. But it is important for me to maintain contact with my past.

|

|

| Zabrze orphanage children dressed in their best in the city of Zabrze |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zabrze, Poland

Zabrze, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Feb 2016 by JH