|

|

|

[Page 277, Volume 2]

by Dr. Avraham Chomet (Khumit), Ramat–Gan

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The Hitlerist organs of power, the Gestapo and S.S. divisions, began to make concrete their criminal plan for the total annihilation and destruction of Polish Jewry during the first days of the German occupation of Poland.

The initial phases of this plan were outlined in detail in secret telefonograms [telegrams sent by telephone], the so called schnell–brief [express–letter], which the chief of the security police [Reinhard] Heydrich sent to the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen [S.S. and police units in charge of security in occupied areas], which were active in the occupied Polish areas on the 21st of September 1939.

A great deal of organization was displayed in the first phase of this plan, which was to undermine and destroy the economic base of the Jewish population – first through pushing the Jews out of their economic positions.

In addition to a flood of anti–Jewish edicts, which were designed to legalize the daily murder and robbery activities on the part of the Hitlerist holders of power, in addition to the bloody terror in the cities and shtetlekh [towns] in regard to the unprotected Jewish population, in addition to the terrifying annihilation actions with exploding and burning synagogues and houses of prayer, in addition to the confiscation of Jewish possessions, the Jews were pushed out of various industrial enterprises, from commerce and trade. The Jewish intelligentsia were removed from their workplaces; Jewish doctors, lawyers, teachers and scientists lost their income.

The right to pensions, annuities and other social insurance was stolen from the Jews and as a result Jewish retirees and war invalids met with great misfortune.

Greatly contributing to the difficult economic situation of the Jewish population in occupied Poland was the German order of the 18th of September 1939, which was published

[Page 278]

at the end of October, according to which Jews were strongly forbidden to possess more than 2,000 zlotes and the rest of their money had to be deposited in a bank in a blocked bank account, from which the bank could pay out [to the depositor] at most 250 zlotes a week.

This edict was later strengthened on the 20th of November 1938 with a decree according to which only 500 zlotes a month were permitted to be paid out from such a savings account. It should be understood that under such conditions every Jewish enterprise, not having the ability to make use of its blocked money, had to cease its activity.

The fate of the Jewish artisans was sad. They were forbidden to move from one workshop to another without the permission of the German officials who held the power and they were also forbidden to sell their work tools.

According to the decrees of the 16th of December 1939 and of the 9th of November 1940, the Jews could not benefit from the support for the unemployed.

According to the decree of the 7th of March 1940, the Jewish population of the entire General Government had no right to benefit from the medical aid from the sick fund, although they had to pay monthly sick fund dues.

From March 1940, the activity of the Jewish credit cooperative was forbidden. Later, when the Jewish Social Self–Help (YISA) began its activity, the distribution of interest–free loans was one of the tasks of the Tsekabe [Central No–Interest Loan Office] Society, which presented YISA a paper about “interest–free loan funds.”[1].

The results of this German extermination action in relation to the Jewish population in occupied Poland did not take long to arrive… During the first half of 1940 hunger and need reigned in Jewish homes.

The Jewish community in Tarnow was not an exception. Here, too, there were clear signs of a state of shock in Jewish economic life during the first months of the German occupation.

[Page 279]

It did not take long before almost the entire population of Tarnow found itself in a state of economic impoverishment as hunger, cold and illnesses reigned in the Jewish neighborhood. Also, the fact must be considered that the number of Jews in Tarnow rose immediately during the first months of the occupation of the city by the Germans because since the month of December 1939 deported Jews came to Tarnow from neighboring and distant areas.

Twenty–five thousand six hundred Jews lived in Tarnow in September 1930[2]. Despite persecutions, shootings and deportations, the number of Jews in Tarnow in the month of March 1942 reached 28,000 souls.[3]

There still were communal workers from before the occupation in Tarnow, who made efforts to help their needy brothers. They endeavored to help in a reciprocal, unorganized way. In place of the kehile [organized Jewish community], the Germans created a Judentrat [Jewish council] whose task, among other things, was to lead the social aid activity on behalf of the Jewish population in the city. A separate aid commission was created at the Judentrat that led the so–called wohlfarht [welfare].

However, the new, horrible conditions in which the Tarnow Jews now had to live – pressed together in more limited areas than before… robbed of stable sources of income – provided very important tasks for the members of the social division of the Judentrat in Tarnow.

According to an order from the Tarnow county chief of the 16th of September 1940, the Judentrat was authorized to demand a kehile tax of the Jewish residents of the city, the previous so–called domestic tax that they had paid before the occupation. In addition, these payments now were designated for the expense of social aid. The Judentrat also received the right to make use of force against every Jewish resident in Tarnow who did not pay this tax and even to arrest them with the assistance of the police.

[Page 280]

|

|

Only in a minimal way could the Judentrat make use of the income from this tax payment for social aid activities. The contributions, the various forced payments and expensive gifts for the Nazi regime organs depleted the limited financial means of the Judentrat.

An important contribution to the social activities on behalf of the Jewish population under the General Government was foreign help.

The limited minimal aid for the impoverished Jewish masses in

[Page 281]

occupied Poland was possible in great measure thanks to the American transports that arrived in Poland beginning during the first month of 1940. They mainly came from three organizations: 1) from the American Red Cross, which sent aid for the entire civilian population – except the Germans, 2) from the American Hoover Commission (political relief) and 3) from the Joint [Distribution Committee], only for Jews.

Later, when the Jewish Social Self–Help – YISA – participated in the first two funds of 17 percent, it also was decided that YISA had to receive 17 percent of the cash grants the NRA [Narodowa Rada Opiekuńcza – National Guardianship Council] was supposed to receive from the taxes that the occupying regime organs collected from the population for social aid. This part was later – starting in May 1942 – decreased to 16 percent.

However, in the month of July 1942 this grant for YISA ceased.

[Among the main help given in] Tarnow was a folks–kikh [public kitchen], where inexpensive lunches were given out. However, this was like a drop of water. Hunger and sickness, robbery and murderous actions were daily events.

A clear expression of the tragic situation of the Jewish population in Tarnow is found in the assessment for the month of May 1940, which the county chief of Tarnow delivered to the German occupying regime with regard to the forced labor of the Jewish population in Tarnow.

He wrote in the report, “The question arose of what would happen to the Jews in the future as a result of my withdrawing from the agreement with the new system in the area of economic and nutritional organization [under which the Jews must provide] more and more from their earnings. Forced labor for the Jews creates the opportunity of employment and some limited nourishment for only a portion of the men, but not for women and children. The solution of the Jewish problem with the increasing reduction of their ability to earn is even more urgent.”[4].

[Page 282]

During this melancholy era of despair and complete helplessness there were individuals in the Jewish social fabric who decided to break through the wall of hopelessness and resignation that ruled the mood of the tortured Jewish masses in occupied Poland. Yidishe Sotsiale Aleynhilf [Jewish Social Self Help] – abbreviated as YISA – was created at the end of May 1940, a society that was legalized by the German administration as a voluntary aid institution (Żydówska Samopomoc Społeczna [Jewish Social Self–Help), with the task of leading all of the public and private social aid activities, to unify all the organizations for voluntary aid, to create the necessary means, distribute the monetary and material gifts, organize, maintain and support all establishments and institutions for social aid and to work with all foreign aid organizations through the intervention of the German Red Cross.

The first administration of YISA lay in the hands of a presidium of seven founders and together with a chairman and vice chairman they constituted the executive, which was to be reelected each year. According to the statutes and regulations, a Jewish social aid county committee was created in the county seat of every German city and county chief, which consisted of five members and wherever Jews lived this presidium had to right to delegates in YISA.[5]

In addition to member dues, YISA could make use of state and communal grants, dispensing cash and items, money collections, lotteries and other gifts.[6]

Four members from Warsaw and three from Krakow joined the presidium of YISA. Dr. Wajchert stood at the head of YISA during its entire existence.

However, the new aid organization in the Jewish neighborhood had a difficult problem of collecting the necessary monetary means to succeed in its great task. The Judentrats were obligated to subsidize the activity of the YISA divisions in the cities and shtetlekh [towns] in the occupied area.

[Page 283]

Yet the Judentrats were the only Jewish administrative bodies during the German occupation that were authorized to demand taxes and various payments from the Jewish population.

In connection with this, the presidium of YISA immediately at the beginning of its activity demanded that the Judentrat designate a significant grant for the YISA committee in its budgets. Alas, this appeal did not result in a response from the local Judentrat.

For a time, the YISA received substantial help from the Joint [Distribution Committee], which immediately placed its funds and reserves in the possession of the Jewish Aid Organization. However, in December 1941, the Joint in Poland was closed and the presidium of the YISA had to seek other sources of income.

In addition to income from members payments and money collections, for which the aid committees were authorized according to the statues of the YISA – as was previously mentioned – its presidium obtained a portion from various taxes and payments that the occupiers charged the Jewish population in the area of the General Government.

In addition to this, the “immigration tax,” a kind of head tax on all adult Jews over the age of 18 in the shtetl, was implemented in by the order of the 17th of June 1940. Thus the income from this tax was designated firstly for social aid.[7]

This income actually made it possible for the Tarnow Judentrat to bring help en masse to the Tarnow Jews who had been taken for forced labor. As Dr. Wajchert describes in his Memoirs[8]: in 1940 the Judentrat distributed over 150,000 zlotes in aid for those Tarnow Jews employed in the camps and work–battalions.

It is worthwhile to relate that for the camps in Pustków, where at first 750 Jews from Dębica, Mielec, Sędziszów, Ropczyce, Wielopole and Tarnow were imprisoned, the Judentrat of these localities had to arrange for a kitchen, provide food for them, provide work tools, dishes and blankets for the imprisoned Jews in addition to support for their families.

A general resident's tax existed in the occupied areas.

[Page 284]

However, as Dr. Wajchert, the chairman of the YISA, explained in his mentioned memoirs[9], the constant resettlements of the Jewish population resulted in the fact that many Jews did not pay this tax. Thanks to the efforts of the YISA presidium, the division of income as a basis for the Jewish portion of this tax was based on the number of Jews who lived or were staying in an area on the 1st of April 1940 (starting with the date the tax became valid and not on the number of Jews who had paid the tax or not).

It was decided that a communal tax that would fall on a portion of the Jews would be paid to the local YISA committee through the county or city chief with the calculation of the 1st of April 1940[10].

On the basis of this regulation the Jewish county aid committee in Tarnow among other cities received a larger grant from this tax[11].

Later the General Governor Frank annulled these designations on the 19th of October 1941 and with the order of the 6th of December 1941 he published a uniform text for the payment of this tax, not mentioning that its income was designated to cover the expenses of the social aid activity – on behalf of the Poles as well as on behalf of the Jewish population, although this tax clearly was created for this purpose.

At the start, the leadership of the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow was placed in the hands of Dr. Szpajzer and, later, after the Gestapo had murdered him in a beastly manner, the chairman of the Tarnow YISA county committee became Artur Falkman, who simultaneously was chairman of the Judentrat in Tarnow. Still belonging to the committee were Y. Lerhauft,

[Page 285]

Yehosha Grinewize and Paul Rajs, who also led the social aid committee at the Judentrat.

At first, as long as Dr. Szpajzer was alive, there was close contact and useful joint work between the YISA county committee and the Judentrat. Later, the YISA divisions in the neighboring localities, which belonged to the Tarnow Social County Committee, such as in Brigl [Brzesko], Bochnia, etc. suffered when the same person stood at the head of both administrative bodies.

As we read in a written report,[12] which the member of the YISA presidium, Dr. Elihu Tisz (a child of Tarnow, active over the course of many years in the Zionist movement in Tarnow, until 1939, lawyer, Zionist and communal activist in Novy Sacz, leader of the cultural and press division of the Jewish World Congress in Stockholm after the war, emigrated to Israel in 1951 and died in Jerusalem in 1953) reported in connection with his appearance in Tarnow in October 1951, “No one in Tarnow knew about a Jewish Social Self–Help [organization]. They only knew the Judentrat, which is not a surprise, because Mr. Rajs served in the reception room of the social county committee in the name of the Judentrat and the division of the Judentrat that gave out various forms of permission, and also was found in the office of the county committee…”

In this report it is also stressed that the Tarnow Social County Committee was no more than a showcase for the Tarnow Judentrat and had very loose contact with the provinces.

In the account written by the presidium of the YISA in Krakow on the 20th of November 1941,[13] we read that Dr. Jakov Gans, the chairman of the YISA delegation in Gumniska, near Tarnow, along with the vice chairman of the Judentrat there provided a certain clarification with regard to the relation between the Tarnow Judentrat and the Tarnow YISA county committee. He [Yakov Gans] and Meir Bazler, the chairman of the Judentrat there, both complained that since the death of Dr. Szpajzer, of blessed memory,

[Page 286]

the Jewish Social Country Committee existed only on paper because Mr. Rajs, who is a good worker at the Judentrat is so busy there that he has no time for the Social County Committee. The same – lamented the delegates – concerns the chairman, Folkman, and the entire county committee is asleep… And although two officials, the doctors Maszler and Pfefer, are there, it is not possible to take care of things with them because they cannot make a decision on any matter. The delegates have asked them to place at least one person on the Tarnow Social County Committee who would be active only in matters of social self–help in Tarnow County.

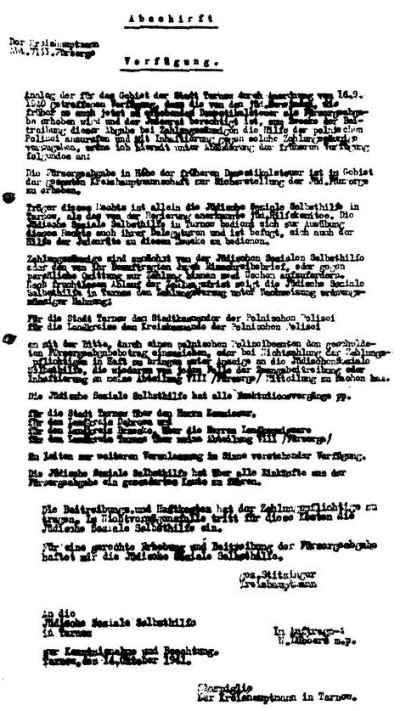

The Judentrat was dependent in all its dealings on the German regime organs whose orders had to be carried out. Because of the necessity of satisfying the transforming desires of the German rulers and providing the illusion that by submitting to the German bandits it would be possible to moderate and weaken the German brutality and because of the difficult economic situation, the Tarnow Judentrat was not capable of allotting a significant grant to the YISA county committee. It is enough to cite the written order, which the Tarnow county chief

|

|

[Page 287]

sent to the YISA county committee on the 3rd of October 1941, in which the latter was ordered to prepare beds and food for 1,000 Jews who were to arrive in Tarnow from Hamburg that day; this assignment was sent with the observation that the stay of the deported Hamburg Jews in Tarnow was expected to last approximately a week, until they received a regular place to stay.[14]

It should be understood that providing 1,000 Jews a place to sleep and with food over the course of even one day was not an easy thing and that there would be large expenses. Burdened with such a task, both the Judentrat and the YISA county committee did not have the opportunity to develop widespread aid activities on behalf of the Jewish population in the already crowded Jewish quarter in Tarnow… Meanwhile, the number of hungry, sick and weary Jews who were robbed of their possessions grew every day. Devoid of sources of income, the great majority were degraded into habitual beggars who were now dependent upon the help of the only aid institution in the Jewish neighborhood, the Jewish Social Self Help Committee, which was identical to the social committee at the Judentrat.

Previously we have mentioned the order of the 16th of September 1940, according to which the Judentrat was entitled to take the pre–war community tax (local tax) from the Jewish population in Tarnow to cover the expenses of the social committee.

The right to receive this “local tax” was given exclusively to the Tarnow county committee of the Jewish Social Self–Help (YISA) in a new order of the 14th of October 1941 – as the only Jewish aid committee recognized by the German government and as expressed by the county chief in the cited order – “Make use of the Jewish Social Self–Help in Tarnow in the carrying out of this authorization with the help of its delegates and of the local Judentrat.”

[Page 288]

|

|

This order also gave instructions as to how to act in relation to the Jews who did not pay the required communal tax sum. In such a case, the YISA committee in Tarnow or its delegates in a particular locality that belonged to the Tarnow county had the duty to demand the payment of the demanded sum over the course of two weeks and if this period elapsed and such a tax obligation proved fruitless that the city or the county commandant of the Polish police had to be informed of this with the request “to help” collect the tax owed and if this was not possible even to arrest the person obliged to pay.[15]

However, the German holders of power made this even smaller aid opportunity in the Jewish

[Page 289]

neighborhood dependent upon safeguards so that their purpose was a means to limit and shrink the aid activity of the Tarnow YISA county committee.

On the 14th of October 1941 the YISA division in Tarnow received a copy of the order of the 2nd of October 1941 from the Tarnow county chief in which the Jewish Social Self–Help Committee in Tarnow was asked to assure that it alone as well as the Tarnow Judentrat required an acknowledgement that it had fulfilled its obligations on behalf of the labor office from every Jew who needed to receive support from the mentioned aid institutions. The YISA committee or the Judentrat had the duty to order from each male, aged 12 to 60, who received support, that every two weeks he obtain a registry card from the labor office[16]. and with it each Tarnow Jew who wanted to make use of the drops of support that the YISA committee or the Judentrat was able to distribute, had to show that they had given their last strength to the German war machine.

The YISA presidium also searched for income from other sources. The German government organs placed trustees not only in the Jewish trades and industrial enterprises. The Jewish houses and locations that were outside the Jewish quarter in Tarnow were placed in the hands of German managers.

Thanks to the efforts of the YISA its local division could make use of the taxation on Jewish houses and places and the trustees gave a portion of this tax for Jewish social aid. This in 1941 the local YISA county committee in Tarnow paid the sum of 16,200 zlotes from this tax.[17]

According to a report from the YISA presidium in Krakow, the Jewish hospital in Tarnow received an allocation of medications and bandage material from the first foreign medical transport through the intervention of the Polish Red Cross.[18]

[Page 290]

Despite the difficult conditions in which it happened to unfold, at the end of 1941 this Jewish Social County Aid Committee still could show important achievements in the area of social aid work for the impoverished and already physically and spiritually weakened Jewish population in Tarnow.

As we read in a report[19]. from the delegate from the YISA presidium in Krakow, Dr. Elihu Tisz (a child of Tarnow and dedicated Zionist activist in Tarnow since before the First World War) – who lived in Tarnow during the days from the 10th to the 18th of October 1942 and learned about the aid activities of the local county aid committee – three people's kitchens were active during this period in Tarnow from which very good meals were given out, in addition to the preparation for the opening of a fourth kitchen. According to this report, the old age and orphans home, the Jewish hospital and the out–patient clinic were found in to be in good condition.

It should be understood that despite the useful activity of the Jewish Social County Committee with the help of the social division of the Tarnow Judentrat, need increased with every day in the Jewish homes in Tarnow… Hunger and illness spread in a terrible manner in the Jewish neighborhood.

The situation of the Jewish orphans and homeless children was very tragic.

“The literally superhuman efforts by the local activists” – wrote Dr. Wajchert, the recently deceased chairman of the YISA, in his memoirs[20]. – “could not extract the tens and hundreds of thousand children from the abyss into which the occupier had hurled them. If the life of the children – whose parents had no income and were exposed to robberies, being caught [for forced labor], arrests, deportations, shootings – was difficult during the first months after the entry of the Germans, it became unbearable after the creation of the ghettos and it reached its highest tragedy after the order that threatened a punishment of death for leaving the ghetto.

The tragedy of this situation became still clearer

[Page 291]

when, according to the order of the 23rd of July 1940, all Jewish communal organizations, establishments and institutions were closed, the only possibility now to develop social–communal activities was in the framework of the Jewish Social Self–Help [YISA].

This closed the gate for the children at all of the schools and there was need and hunger in the Jewish homes – all of this forced the leaders of the Tarnow Jewish Social County Committee to carry out concrete aid work on behalf of the neglected Jewish children in the city.

Thanks to these efforts it was possible during a given time to support the Jewish Orphans Home for Jewish orphans and to feed and clothe a large number of poor Jewish children until the first deportation in Tarnow in June 1942[21].

We learn about the manner and extent of this aid activity on behalf of the Jewish children in Tarnow during this period from a written account, which the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow sent to the presidium of the YISA on the 8th of October 1941[22]. As emphasized in this report, the activity in Tarnow was based on the situation on the 1st of August 1941:

a) The Jewish orphan home, which had been in existence since 1919 and on the mentioned day the following were supported there:

10 children aged 3 to 7

47 children aged 7 to 14

13 children aged 14 to 18

That is a total of 70 children.

b) From March 1941, a feeding station for Jewish children was active in Tarnow and as a result of the conditions on the 1st of August, supplementary nutrition was provided there twice a day for

33 children aged 3 to 7

689 children aged 7 to 14

[Page 292]

The social division at the Judentrat in Tarnow was busy gathering clothing and underwear for the children.

As we learn from this report, during this already difficult time for Tarnow Jewry, there were Jewish families in Tarnow who shared the little bit of food they had with hungry Jewish children.

As we learn from the previously mentioned report, much was done in the area of sanitary–medical aid activity. A sanitary commission was active at the Judentrat, which took care of medical aid and distributed medications without cost, controlled the health conditions of the children and supervised the hygienic conditions of the apartments.

In general, as the report quoted above states, during this period approximately 2,000 adult Jews received food at the public kitchen every day.

As we see, during the second half of 1941, the social aid activities in Jewish Tarnow stood at a certain level. The destructive process in Jewish economic life in all localities that belonged to the Tarnow Social County Committee already had led to a situation of complete impoverishment of the Jewish population, who already wrestled with the terrible nightmares of hunger, cold and illnesses.

In a letter from the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow of the 29th of October 1941[23]. to the presidium of YISA in Krakow, the tragic economic conditions of the Jewish population in all areas of Tarnow are described by the Jewish Social Aid Committee. And as we read there, “the absorption of the 'community tax' for social aid can be surmised because of the general impoverishment of the local Jewish population and its even greater difficulties.” It is shown in this letter that in August 1941, all three public people's kitchens that were active then in Jewish Tarnow provided 145,333 mid–day meals.

[Page 293]

But thanks to the systematic aid on the part of the central [office] of the YISA in Krakow, the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow fulfilled its task in a limited way and it was able to support several institutions in Tarnow that brought a minimal [amount] of help for the local Jewish population and in a very limited measure also in several localities that belonged to the Tarnow Social County Committee.

Thus, for example, the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow, in a letter of the 20th of November 1941 to the YISA presidium in Krakow[24]. certified the receipt of the sum of 5,100 zlotes to distribute, 4,000 zlotes for the feeding activities, 1,000 zlotes for help for the Jewish children and 100 for the sanitary aid in Ryglice. As is emphasized [in the letter], the Joint provided 2,550 zlotes of this sum.

In general, we can establish on the basis of the remaining minutes of the meeting of the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow, which are in the archive of the Jewish Historical Commission in Warsaw, that until the end of 1941 the members of this committee, despite the great difficulties, showed an active nimbleness in the area of distributing aid for the still existing Jewish social institutions in Tarnow.

As we learn in the minutes[25]. of a meeting of the Jewish Social Aid Committee in Tarnow of the 31st of October 1941, the latter paid out in October 1941:

1,000 zlotes for the Jewish old age home in Tarnow

1,000 zlotes for the Jewish orphans' home in Tarnow.

From a second set of minutes[26]. from a meeting of the same committee on the 30th of November 1941, we again learn that in November 1941 was paid:

2,000 zlotes for the division of infectious diseases at the Jewish hospital,

1,000 zlotes for the out–patient clinic at the Jewish hospital to buy medicine.

1,500 zlotes for renovating the ovens at the Jewish old age home.

The Jewish Social County Committee also received grants from the Polish Main Social Services Council (Rada Główna Opiekuńcza) in Krakow.

[Page 294]

This we know from a letter from the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow to the above–mentioned Main Council in Krakow of the 21st of October 1941[27]: that the Tarnow committee received 100 pairs of wooden shoes with shoelaces and immediately the next month, the 18th of November 1941,[28] the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow was designated the recipient from the Polish Main Council:

170 kilos “bacon” (pig meat)

100 blankets

100 liters fish oil

The members of the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow placed great weight on the question of nutrition because the majority of the Jewish population in Jewish Tarnow during the second half of 1941 already was dependent upon the people's kitchens as the only source of nutrition. The Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow actually went in that direction, and as we learn from written information from this committee of the 11th of December 1941[29] to the presidium of YISA in Krakow, the fourth people's kitchen was opened on the 14th of December 1941 at Lwowska Street 7, which was mainly designated for working artisans.

During this period the active members of the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow made additional attempts to create new work opportunities for Jewish working people, particularly for the adult Jewish young people.

We learn this from a letter of the 17th of December 1941 from the presidium of the YISA in Krakow to the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow that the latter made attempts to organize trade courses in Tarnow.

As Dr. Wajchert related in his memoirs,[30] the Jewish Social County Committee in Tarnow planned to found a farm on the Goldman family's farm (the so called Goldmanuwke), but as this estate was confiscated by the Germans on behalf of the Ukrainians, the YISA presidium in Krakow attempted to free this area from confiscation. However, at the end of 1941

[Page 295]

this devilish game by the German hangmen ended; the true intentions of the German murderers in regard to Polish Jewry began to be revealed.

After the outbreak of the German–Soviet War, the Germans began to implement the long–planned extermination activities in regard to the Jewish population in the Polish cities and shtetlekh [towns].

During the second half of 1941 the German preparations for a systematic action to physically annihilate the already spiritually and economically weakened Tarnow Jewry began to be more apparent in Tarnow.

Actually, at the time when the process to eliminate the Polish Jews from economic life had ended and the number of Jews grew larger who had been robbed of their workshops and who remained without income and without the ability to feed their wives and children, as we described previously in another place, the Joint, whose funds in the greatest measure made possible the aid activity of the YISA, was closed.

Consequently, the situation of this aid institution was now very serious. At the end of March 1942, the BVF[31] issued an order that the YISA presidium was authorized to carry on the activity of the Joint and was entitled to take over the foreign transports that arrived at its address.[32]

During the first month of 1942 a suspicion awoke in the hearts of the Tarnow Jews that the German murderers also were preparing a slaughter in Tarnow, in addition to the “deportations” of the Jewish population. Stories spread that the first to be deported would be the poor Jews who received support from the Wohlfahrt [welfare] at the Judentrat. Jews in massive numbers refused support from the Judentrat and even tried to have their names erased from the list of those receiving charity.

[Page 296]

When the tumult of the work cards with the various stamps began in Tarnow, Tarnow Jews were forced to enroll at a workplace at any cost, believing that work would free them from deportation, about which they already heard frightful reports. Artisans' communities arose in the city – work enterprises – created by artisans of various trades who worked for the German military.

As we learn from material of the 25th of March from the YISA presidium[33] the Jewish Artisans Union in Tarnow created such worker communities for tailors, laundresses, locksmiths, shoemakers, gaiter makers, harness makers, saddle makers, hat makers, upholsterers. German firms also appeared in Tarnow that allocated positions for Jewish artisan communities[34].

Eskate, Ostbahn, Latsina, Krakauer–Confectionary–Julius Madritsch, Okon, Zentrale für Handwerklieferungen [Central Agency for Handicrafts] were such German enterprises in Tarnow.

At first Jews employed in the handworker unions and work communities or in the German enterprises were protected from expulsion. A stamped pass or employment from a German firm to which the Jewish workshop had supplied their production or at which they worked often saved [them] from deportation to a death camp.

Tarnow Jews worked at various German workplaces outside the city. Approximately 400 Tarnow Jews were imprisoned in the Pustków labor camp, outside Dembitz [Dębica], and more than 1,000 Tarnow Jews were employed by the German Wehrmacht [unified armed forces] in various localities.

There was a lasting struggle in connection with making use of the Jewish work force for the German war machine between the S.S. and the military industry around the question of whether this Jewish work force should be kept alive.

Several Christians stood out in this struggle on behalf of the Jews

[Page 297]

such as Julius Madritsch, the owner of the large textile factory, Robert Wagner, the director of the Central Agency for Handicrafts, and Oskar Schindler, the owner of the enamelware factory. A number of Jewish workers were employed in these enterprises and thanks to this a handful of Jews were saved from certain death.

As Dr. Wajchert related in his Memoirs (third volume, p. 287), at a meeting of the representatives of the police and administrative organs, which took place in Krakow on the 19th of June 1942, in order to give a report about the anti–Jewish murder action which had taken place, the S.S. and police leader Scherner provided information about the security situation in the Krakow district, emphasizing that among others there were in Tarnow among the residents there 32,000 Jews – 8,000 employed at various work.

It is worthwhile at this opportunity to mention that in the first half of 1942 the number of Jews in Tarnow grew because of the transports of deported Jews [who arrived in Tarnow] from the surrounding shtetlekh [towns], where a number of ghettos were liquidated at that time.

The wage for the Jewish workers in these enterprises was minimal; Jews often paid so that they would be employed because the work was supposed to save them from deportation to Belzec, to Auschwitz or to another death camp.

The terrible material situation of the Tarnow Jews did not end by giving their strength to the German military machine. The hunger wore out the old and young. With the greatest effort, the Social Self–Help Committee and the Wohlfart at the Judentrat kept at its activity of supporting the four people's kitchens in Tarnow and in such conditions it was difficult to guard the city from epidemics. During the first months of 1942 typhus broke out in Tarnow. From the already mentioned material, which the presidium of the YISA in Krakow sent to the Central Agency for Handicrafts on the 25th of March 1942, we learn that the health conditions of the Jewish population in Tarnow, thanks to the energetic mass prevention means, was satisfactory and that from the 1th of January 1942 to the 2nd of March 1942 there they noted

[Page 298]

that 45 local and 64 – mainly from the camp in Pustków – fell from typhus[35].

The first deportation in Tarnow was carried out in June 1942, during which approximately 10,000 Jews were murdered in Tarnow itself and the second 10,000 Jews were deported to Belzec. The ghetto in Tarnow was created after this murder action. The YISA division in Tarnow in the new conditions now organized its aid activity and they tried to obtain certain concessions for the tired Jewish population from the local German government agents.

However, right after the first horrible wave of bloody barbarism in the Tarnow ghetto, the German government organs communicated to the chairman of the Jewish Social Self–Help, Dr. Wajchert, on the 29th of July 1942 that the YISA must be dissolved – and its role in [distributing] general grants in the amount of 17 percent were taken from it.

After the second bloody deportation in the Tarnow ghetto, in August 1942, after long interventions and negotiations with the managing committee, on the 20th of October 1942 the presidium of the YISA continued its social activity. The name of the organization was changed and now it was called Yiddishe Untershtitsungs Zentrale [Jewish Support Central] (YUS). The presidium as well as the local division could engage in its aid activity as before. Thus, the YUS division in Tarnow was authorized to bring help to the Tarnow Jews who were imprisoned in the camps, particularly to supply medicine and bandage materials for them.

Of important significance was the decision that the money for the fulfillment of the social tasks of YUS finally had to be extracted from the Jewish population itself[36].

With the ban [on distributing funds] and with again immediately permitting the activity of the Jewish Social Self–Help, even under a changed name, the German hangmen intended to fool the Jewish population and to throw a veil over their

[Page 299]

very devilish preparations for further Jewish slaughters. In order to create the impression that after the last murder action in June and August 1942 in the cities and shtetlekh under the General Gubernia the surviving Jews had the opportunity to work on behalf of the German enterprises and thus save their lives, an order was published on the 10th of November 1942 in the area of the Krakow district according to which all Jews who had been hidden in the villages and shtetlekh could return and settle without punishment in one of the listed five cities – that is, Krakow, Bochnia, Tarnow, Rzeszow and Przemysl and be organized in these so called “remnant ghettos.” Thousands of Jews let themselves be fooled and fell victims in the murder actions immediately carried out by the Germans in these cities. And to draw the rope tighter around the necks of the surviving Jews, the German police and security organs in the General Gubernia, who were involved in the matters of social activity, in an order of the 18th of November 1942, annulled the previous decisions with regard to the founding of the Jewish Support Central (YUS). In the explanatory statement of this order it was emphasized that as the S.S. Reichsführer [commander of the S.S.] had conflicting official duties, the need to increase the deportation of the Jews while at the same time provide work–capable Jewish men and women to support the military economy and the armaments industry . The workers would be under the supervision of the S.S. and of the police and the activity of the Jewish support activity would no longer be necessary. During this time, all the Jews – with the exception of the above who were recorded as capable of work and confined in the labor camps – would disappear, so that basically all further social measures on behalf of the remaining Jews would lie in the hands of the S.S. and the police[37]

On the 1st of January 1942 Dr, Wajchert communicated about the dissolving of the Jewish Support Central for the General Gubernia and all of the money and material property was confiscated in order to secure its existing obligations.

[Page 300]

During the first half of 1943 those Jews still alive in the Tarnow ghetto no longer had any illusions that they had [not] been sentenced to death, and understood they were in a hopeless situation. In the month of March 1943, Dr. Wajchert even succeeded in persuading the occupying regime organs that the activity of the Jewish support central [committee] should be permitted to start again. But in August – barely five months after renewing the YISA activity – the Tarnow ghetto was finely liquidated. Several thousand Jews were deported to Auschwitz and around 2,000 young Jews were sent to Płaszów and Treblinka, to the labor camps there. Almost all of the bunkers in the city were torn open and hundreds of Jews were discovered and shot. Then the occupiers again – for the third time – forbade the aid. The remainder of the Jewish population in Tarnow, the 300 Jews of the clean–up command, starved and worked at hard labor on behalf of the German hangmen. And in February 1944, when even this small group of exhausted Jews was deported, some to Szebnie and some to Płaszów, Tarnow was Judenrein [free of Jews].

Original footnotes:

by Dr. Avraham Chomet, Josef Kornilo

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The anti–Semitic policies of the Hitlerist occupation regime had as their purpose the brutal and barbaric annihilation of the Jewish population and for this purpose the Nazi murderers used every possible criminal means. In order to annihilate the Jewish population systematically and methodically, the Nazi hangmen drove the weary Jews into a ghetto during the deportation actions, into the surrounded by locked and guarded gates. The Nazis made any contact with the outside world impossible and cut off the possibility of Jews escaping from this hell as well as contact with relatives and friends who could provide help, because there was the threat of death for leaving the ghetto… And every Christian who hid a Jew or tried to help with a piece of bread would receive the punishment of death…

The Tarnow Jews also found themselves in such a situation… A ghetto was created in Tarnow immediately after the second deportation, after the mass murder of over 20,000 Jews. The Jews imprisoned in the Tarnow ghetto now felt entirely surrounded, besieged… Hunger and illness now raged in the overcrowded Jewish residences. The true intentions of the Nazi murderers were now clear… Therefore, the Jews began to search for ways to save themselves… They began to build bunkers and other hiding places.

There were cases of people escaping from the ghetto and furnishing themselves with Aryan papers… There were individual cases where Poles showed full feeling and compassion and brought help to the Jews imprisoned in the ghetto, mainly by creating hiding places on the Aryan side.

There were cases where peasants hid several people, Jewish families, escapees from the ghetto for a reward. It is described in the first volume of the Tarnow Yizkor book,

[Page 302]

that thanks to this help, several souls from the Postrong, Landman, Mitler and Betribnis families survived…

There were very few courageous Christians who ignored the dangers that lay in wait at every step of the way; placing their own lives [in danger] and standing face to face with death, they struck out their hands to the persecuted Jews and many were saved from a sure death.

We call them “the Righteous Among the Nations,” for which Yad Vashem in Jerusalem has arranged a separate “Garden of the Righteous” on the Mount of Remembrance, and each of these Christians who, with superhuman courage, saved Jews during the Shoah era, are recognized with the honor of inclusion as “the Righteous Among the Nations” and with the planting of a tree in this garden.

We collected the details about a handful of Christians who, during the time of cruel, murderous actions in the Tarnow ghetto, in their deep human nobility showed superhuman courage and self…sacrifice and spared no strength or effort to save Jewish lives from the Nazi hell.

|

|

[Page 303]

The place of honor in the pantheon of the Righteous Among the Nations is occupied by the noble, Viennese Christian, Julius Madritsch, and his co–worker, Raimund Titsch[a]

Jews rushed to work for the German war industry, during the era when the Nazi occupation under the Galicianer General Government living with the illusion that the work would protect them from death.

Madritsch had already opened a tailoring workshop in the Krakow ghetto in 1941, in which he employed hundreds of Jewish workers, provided them with the necessary food and applied much effort and exertion – often risking his own life – to protect the workers from selections and deportations.

Madritsch opened a branch of his Krakow tailoring enterprise in Płaszów and later in Tarnow where a large number of clothing workers had lived since before the war.[1]

Raimund Titsch, also a German Christian from Vienna, was helpful in the leadership of the clothing workshop in Tarnow. He often placed his own life in danger giving his workers news from the warfront. The number of Jewish workers was up to 500 and those who survived the Nazi hell cannot praise enough the humane and auspicious conditions in which they were able to work in this enterprise.

In the forward to the German memoir that Madritsch wrote and published after the war in 1962, under the title Menschen in Not! [People in Distress! ], Dr. David Shlang, the general–secretary of the Zionist Federation in Austria, wrote: In order that we can give the appropriate honor to the author of the book, we would have had to live in the ghetto, we would have had to see the rows of people who worked in Julius Madritsch's workshops and were led through the small gate in the ghetto wall every day… The people who had the good fortune to be assigned to Madritsch's work–commando [group of forced laborers] felt as if they were the “chosen ones” of the ghetto and later, the same way at the concentration camp in Płaszów–Krakow… The unfortunate Jewish population that was locked out of

[Page 304]

human rights, found in the person of the author a true supporter – he often was called the Angel of Płaszów.

During the entire time, all of his workers received meals from the factory kitchen; thus Madritsch received permission to reward every worker with two loaves of bread a week from his own pocket. Thanks to his efforts, all of his approximately 500 Jewish workers at the Tarnow clothing enterprises were moved to Płaszów in the month of September 1943 during the liquidation of the Tarnow ghetto and in Płaszów received employment in the Madritsch clothing factory there.

In the most difficult conditions, when it appeared as if everything was lost, both, Madritsch and Titsch did not give up and with extraordinary energy and stubbornness, they searched for means and ways to save their Jewish workers from certain death.

Even at the end of the Nazi anti–Jewish annihilation action, when the Nazi hangmen decided to liquidate the Płaszów camp, the two genteel Christians did not forget their unfortunate Jews sentenced to death. They succeeded, with great difficulties and efforts in saving 100 of their Jewish workers, creating work for them in the enterprises of Oskar Schindler in Czechoslovakia where they awaited their liberation by the Allied army.

The Jews saved in such a manner, who emigrated to Israel, did not forget the heroic self–sacrificing good deeds of these two genteel Christians. Both, Julius Madritsch and Raimund Titsch, in an expression of thankfulness and in recognition of their heroic actions in the area of saving Jews persecuted by the Nazis rulers, were given the honor of entering the pantheon of the Righteous Among the Nations.

In April 1965, Madritsch and Titsch, who were invited as guests by the saved “Madritscher” [those who were saved by Madritsch] to a solemn welcome reception on the Mount of Remembrance in the Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations. Madritsch and Titsch each planted a tree there and the leaders of Yad Vashem gave each one a special Certificate of Honor with the dedication: “He who keeps one soul alive, it is as if he had kept the entire world alive.”

[Page 305]

|

|

In a letter that Julius Madritsch wrote in March 1966 to Josef Kornilo, he expresses the wish to come to Israel immediately to meet again with the surviving Jews and to see how the tree he had planted had grown…

Superhuman heroism and moral elevation during the Nazi occupation of Tarnow was shown by the Tarnow Christian, Maria Dyrdałowa, who knew no fear and overcame the most difficult obstacles when it was a question of saving a Jewish child from certain death. Herself a poor woman who worked hard for a piece of bread, a servant in Jewish homes for many years, she possessed a genteel heart full of understanding and compassion for human suffering. With full knowledge of the boldness of her deeds, she often risked her life to save unfortunate Jews.

“Maria Dyrdałowa is among the most beautiful personalities among the Righteous Among the Nations (we read in a treatise that was published in the local newspaper, Letste Neies [Last News] of the 4th of November 1964, in which the details about her self–sacrificing deeds), “which so rarely brightened those cruel days when it was shown that the image of God was eternally erased from the earth and only the animal remained…”

And when one learns of the courageous and purely humane action

[Page 306]

|

|

of Maria Dyrdałowa, one must admire the unsophisticated, poor and modest woman who radiated goodness and showed such courage and strength in opposing the angry devils of that dark time.

After the imprisonment of the Tarnow Jews in the ghetto, when Maria Dyrdałowa began to trade and would travel with her “goods'” from city to city, she arrived in Bochnia and there in the house of one of her customers heard

[Page 307]

|

|

the cry of a child… According to the statement of the woman with whom the child was found, this was a Jewish child of seven months whose parents had been shot by the Nazi murderers and now there was no one to pay for raising and hiding the child. Maria Dyrdałowa did not hesitate for long, she gave all of her goods to the Christian woman and took the crying Jewish child…

[Page 308]

|

|

Maria Dyrdałowa's life now was difficult and filled with danger… Death hovered in every corner… Tearing herself from the talons of the Gestapo because of suspicion that she was hiding a Jewish child, she had to wander from one city to another… And even after the war, she had to wrestle with all kinds of difficulties…

[Page 309]

When the girl she saved from Bochnia was 15 years old Maria turned her over to the Jewish Youth House in Tarnow from where she emigrated to Israel in 1957. Elisheva, this was now the name of the girl who had been saved – spent several years in Neve Eitan [a kibbutz – collective community], and from there she moved to Tel Aviv and a little later she married Avraham Patt, a young man from Bnei Brak. Elisheva remained in heartfelt contact with Maria Dyrdałowa, and considered her as a “mother.”

On the page of the magnificent, heroic actions of Maria Dyrdałowa are the additional records of the history of the two children of a Tarnow Jew, a certain Moshe Lewinowski… When he became very sick and he felt that he was going to die, he summoned the woman he was friendly with, Maria Dyrdałowa, and asked her to take and raise his two children, and principally, that she should make sure that they remained Jewish children and would go to Israel.

Maria Dyrdałowa did not refuse and undertook the fulfillment of Moshe Lewinowski's testament… A difficult road of effort and exertion began again, until she and the two children arrived in Israel and she carried out the promise she had given to Lewinowski.

For her courageous deeds, for her humane conduct, for her self–sacrifice in saving Jewish children from death during the Nazi rule, Yad Vashem bestowed on her the honor of belonging to the Righteous Among the Nations and as such she planted a tree in the Garden of the Righteous on the Mount of Remembrance.

Another Polish Christian from Tarnow, Bronislawa Gawelczyk, planted a tree in the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations in Jerusalem.

It was close to the end of the liquidation of the Tarnow ghetto when the murderous extermination action against the remnant of the Jewish population in Tarnow reached its highest point of cruel slaughter. In their despair, the Jewish mothers searched at the very least for a way to save their youngest children who were the first victims of Nazi brutality. Mrs. Ela Hofmajster, the mother of a daughter, Sura, who was not yet two years old, made such an effort.

[Page 310]

|

|

And when the Nazi hangmen threw themselves like wild animals on the Jewish children during the last resettlement actions in the Tarnow ghetto in September 1942, Mrs. Hofmajster turned to the Christian woman, Bronislawa Gawelczyk, known to her as a client acquaintance from business, with the request that she take the child who had been in a bunker for several months… The Christian woman agreed immediately and took the small Surala, not asking for any payment. There also was no lack of hardships and dangers from bad neighbors, informers and blackmailers. Mrs. Bronislawa went through the most difficult trials with extraordinary heroic firmness and hid the small Surala for four months, despite the Nazi threat to shoot every Christian who dared to provide help to the Jews.

Surala's parents, her mother and father, perished in a Nazi death camp… After the war, in 1947, Sura emigrated to Israel with the Youth Aliyah, where she graduated from a Hebrew middle school and the Judicial

[Page 311]

|

|

Law School at Hebrew University in Jerusalem… She then married and remembered her rescuer, Bronislawa Gawelczyk…. And to express this sincere feeling of thankfulness of this genteel Christian woman, Surala and her relatives who had survived the Nazi hell invited her to Israel.

Mrs. Gawelczyk also was given the distinction of entering the pantheon of the Righteous Among the Nations for her heroic deeds during the Shoah era and was given the honor of planting a tree in the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations.

To the number of Tarnow Christians who in the most difficult conditions and with mortal danger during the Nazi occupation of Tarnow saved Jews, should be added Josef Banek and his daughter; Irma. They hid several Jews for three years in their residence and thus saved them from certain death. The deeds of Josef Banek and his daughter Irma, who lived in Tarnow on Czelona Street, were confirmed by the district committee in Tarnow in its writing of the 10th of August 1947. These two Polish Christians hid and cared for, without payment, the Tarnow Jews: Chaim, Dora and Inge Betrubniss as well as Shmuel Rapaport, Sabina Lichtinger and her family members. These two Christians also will soon be recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

[Page 312]

Among the limited number of Christians who overcame fear and were active in the Polish underground movement, Kazimierz Jarmula, who lived in Tarnow on Paderewski Street, helped Jews a great deal during the Nazi rule in Tarnow.

He was arrested in August 1940 by the Gestapo for “harming German interests” and he was deported to Auschwitz several days later and, from there, to other concentration camps until he was freed by the Allied Armies in 1945. This heroic Christian soon also will be given the distinction of becoming one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

|

|

Footnote:

Translator's footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Tarnow, Poland

Tarnow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 Sep 2022 by LA