[Page 31, Volume 2]

To My Beloved Town That Is No More

by Yaakov Fleisher (Rechavia, Israel)

Translated by Daniel Kochavi

Where have you gone? Years of my youth and golden dreams, years of naive childhood, warm hearts and eternal friendships. Nights of discussions, evenings spent studying the language of the homeland we yearned for [Israel]. Where are you near and dear opinionated sons of the Youth Movements – each with its own ideological view of a future full of glory?

Hikes in the Tatra hills and Carpathian forests, Shabbat hikes under the group flag, nights by the bonfires in the woods in unfriendly surroundings where our bewitched spirits soar to the new homeland, to a society built on a life of creation and longings, a society physically and spiritually struggling to rebuild after a thousand year of ruin and creates new stones for a nation's house. Although some friends, relatives, brothers and parents rejected these ideas, the sun shone on the horizon and the stars beckoned from above…. youth convoys streamed on, echoing joyful songs upon departure, trains packed and seaports crowded with Halutzim from all over Europe,

|

|

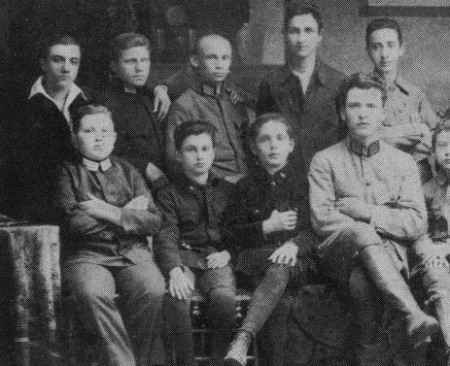

Group of Tarnow Shomrim in 1920

Seated from left: Engelhart Artek, Traum Sigmund–now in Australia, Handler Yeshayahu (now a doctor in Tel Aviv), Kaufman Mordecai, (–), Zaltz Yaakov

Standing from the left: Zimmerman; Manek Rodner; Speizer Yaakov; Margolit Leon; Koperman Israel; Swartz Artek (now in Kibbutz, from Rechavia); Eisenberg |

[Page 32, Volume 2]

|

|

“Hashomer Hatzair” in Tarnow year 1921 – Troop “Zev” (trans. Wolf)

Sitting from left in order: 7–Zemel, 8–Ressler, 9–Vachtel Hayim (today a Doctor in Tivon)

Standing: 1–Tornheim, 2– Pris Milk,3–Stein,4–Lintser,5–Omanski Yaakov,6–Brown Henek (now in Tarnow)

In the middle: Kornilo Yoseph (now in Israel) |

with faithful sons eager to rebuild the beckoning homeland. Oh!!! How worthy the years, how joyful was the soul yearning for great accomplishments, to embrace the world, to conquer deserts and subdue all resistance.

Poland, the adopted motherland and enchanted country, its beauty drew the soul and relieved the longing for rest. The abundance of the country satisfied physical needs but did not bring rest to the soul. An eternal flame burned deep in our heart and drove a search for the uncertain tomorrow, pulled the spirit and promised to fill an inner void.

Individual longings became the longings of the society. Societies and groups were created, organized youth grew into a social way of life, created sign–posts, an unending struggle between the individual and the society

[Page 33, Volume 2]

but in the end the movement won, one for all and all for one, only external barriers seem to separate them. So, my beloved town; cradle of childhood and dreams, its rich and glorious past was abandoned like a lover betraying his beloved for a creation of new dreams and longing.

To Israel To Fulfill Dreams

The snow melted, the sun shone and spring arrived. Friends, members of the [Zionist] movement, left in droves. “Will we meet again?” cried the sons. The ships sailed over stormy seas to distant shores that were so close to the heart and soul. Fear of the unknown grew; can the will and strength endure? The land ate her sons. Years of hunger and disappointments went by. The reality was far removed from the ideal. The limited ability was far from the aspiration. Weak bodies and broken spirits yielded to the cruel realities. Fresh graves appeared suddenly here and there hidden in the shadow of eucalyptus trees in cemeteries, the name of a friend or acquaintance from the town memorialized the person who was disillusioned in his long travel. Many felt they found their way back to a past that had been left behind and forgotten

|

|

Meeting of Halutzim from Tarnow after their release from prison in 1924

(they were caught during their illegal entry to Israel)

Seated first on top row from the left: Yitzchak Kornilo (now in Israel)

Seated below in the middle: Friedman Bear |

[Page 34, Volume 2]

|

|

Meeting of Tarnow Halutzim in Eretz Israel in 1925

Sitting from the left: Sturm Pinchas (now in Israel); Klapholtz Ezra (now in Israel) ;(–), (–), Rubin Yaakov (now in Israel); Shreiber Zvi

Standing from the left: Shanhoff Moshe, (–),Faust Shmuel, (–), Levanoni Zev (now in Israel), Frankel, Kornilo Yitzchak (now in Israel), Pintshoski |

as if they had returned “home”. They felt that they had overcome their despair and were pursuing their previous path and so could follow history; – however history quickly changed their fate forever….

The years of hardship and disappointment in the chosen land [Israel] passed and a period of flourishing and prosperity followed. New kibbutzim and settlements conquered the desert, widened the frontiers and fortified the people of the book. Remarkable agricultural achievements ensured the stability of their new home in Israel. Cities grew, industry flourished. But then the Holocaust threatened everything that was left behind. The community once enlisted bodily and spiritually in the defense of Israel, the homeland. Then they turned around to join the war against the Nazi invader that was prepared to destroy everything.

Awareness of the Shoah

Slowly the news trickled in, the news of the Shoah reached us. The unbelievable became fact. The Nazi beasts managed to destroy the pride of the Jewish community in Europe, six million victims died through

[Page 35, Volume 2]

|

|

| Survivors of the Tarnow Jewish community at a memorial near the common grave of Jews killed in the Buczyna forest in Zbylitowska Góra (outside Tarnow) in 1967 |

no fault of their own. Historical horrors exceeded any imaginable scale. After great hardship, the survivors reached Eretz Yisrael and the cruel truth came to light. The glorious past had been wiped out in no time and only a few survived. Flowering Jewish towns and communities in Europe had disappeared, entire families were torn away from the Jewish tree. My beloved town, the joy of my life, betrayed her purpose. Tarnow, a town and mother in Israel, with thousands of Jews, rich and poor, was decimated. This holy, glorious and active community was desecrated by the Nazi troops. The heart of her youth stopped beating. On the other hand, the non–Jews remained seemingly whole with their looted riches. They did not suffer much but inflicted much pain. The glorious New Synagogue in the heart of the Jewish community with its high dome that seemingly competed with the towers of the Christian churches was sacrificed for the idol of destruction and racial hatred. The only remainder of the New Synagogue's once great past and its grand building is a single scorched column that was rescued and serves as a monument over the large common grave in the ancient Jewish cemetery. One of the survivors, a stone mason, carved words of deep meaning into the column – “And the sun shone and was not ashamed – 25000 Jewish martyrs are buried here, innocent human beings, sacrifices to the Nazi beasts. The tombstone enclosed all those killed here”– All this happened in 1942, in the 20th century, a century of scientific and technical achievements, a century of highest values and ideas in the world.

[Page 36, Volume 2]

The Future

History quickly passed over the Shoah. The State of Israel was created. Many survivors of the sword [Nazis] found a home there. The state flourished in spite of many obstacles and attacks. It created a faithful and secure home for Am Israel (people of Israel) living in the Diaspora.

Years have passed and gone – the glorious past is long gone. But a flame hissed for generations in my beloved and lost town of Tarnow, and hundreds of similar communities in the Diaspora. This flame became a strong fire that destroyed generations. But it led to the foundation of Medinat Israel (the State of Israel)!

My sacred Tarnow community! May your memory be blessed and entwined in the creation of the homeland [State of Israel]. And your cherished sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, tortured sons and mothers who collapsed on the long and hard road to the new homeland and are no longer with us, you will remain forever in our hearts!

[Page 37, Volume 2]

Contribution to the History of Jews in Tarnow

(Facts and Events)

by Dr. Avraham Chust (Comet), Israel

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

– 1 –

Blood Libel in Tarnow in 1844

A periodical, an impartial weekly of Jewish interests, entitled Algemeine Zeitung des Judentums [General Newspaper of Judaism], was published in the first half of the 19th century in the German city of Leipzig in the German language edited by Dr. Ludwig Philippson. From time to time, correspondence from Tarnow was published in this periodical, which makes it possible for us to become acquainted with the life and achievements of Tarnow Jewry in that era.

Thus we learn from a correspondence from Tarnow that was published on the 29th of April 1844 (no. 18) about a blood libel in Tarnow that unsettled the entire Jewish population in the city. According to what is reported in the correspondence, an 11–year–old Christian boy disappeared on the 25th of April 1844. Suspicion fell immediately upon the Jews, that they had grabbed the boy in order to slaughter him for Passover. On the same evening, the local police with the help of military members, searched all of the Jewish houses for the disappeared boy. In addition, help was called for from the peasants in two neighboring villages, with the task of searching the suburbs of Tarnow. All of the streets on which Jews lived were guarded and the house and residence of the rabbi was thoroughly searched. There were searches of the butchers and the bakeries where the matzos were baked. The flour there even was sifted… As we read in the above–mentioned correspondence, all of the people who were employed in making matzos were investigated and, after the

[Page 38, Volume 2]

investigations, everyone of them was searched to see if they were carrying blood–filled vials.

And although it was shown after a thorough search that the suspicion that had fallen on the entire Jewish population was completely groundless, and despite how the correspondent from Tarnow emphasized it [that the suspicion was unfounded], the Christian population retained its belief that the Jews had murdered the boy to make use of the Christian blood.

It was fortunate that several days later the boy was seen in a locality near Tarnow… The correspondent said that there is no doubt that he [the boy] had been hidden so that the agitated mood would not dissipate too soon.

Priests Attack Jewish Merchants Near the Castle Hill…

In 1965 a collection of monographs about Tarnow and its history, entitled Ziemia Tarnowsa (The Tarnow Earth) was published by the provincial committee in Krakow in its publication. A treatise entitled Fun der Fargangenheit fun Tarner Erd [From the Past of Tarnow Earth] was written by the young Polish historian, Josef Duczik, who writes that “an interesting case took place in 1629, when priests beat Jewish merchants who would come to Tarnow not far from the holy Martin–Berg (Castle Hill – ed.) because they did not give the priests the appropriate respect. (p. 27).”

About Improving the System of Teaching the Jewish Religion in the Middle Schools in Tarnow

As is reported in the previously mentioned Algemeine Zeitung des Judentums, in a correspondence from Tarnow on the 17th of December 1855 (no. 51) – the Galician state government demanded that the managing committee of the Jewish kehila in Tarnow announce a competitive test for teachers of Jewish religion for Jewish students in the gymnasia� [secondary school] and the Real School in Tarnow. In connection with this decree, the newspaper mentions that the subject of the Jewish religion in the Tarnow gymnasia� [secondary school] was taught in a completely unsatisfactory manner. It was very sad that one of the largest kehila� in Galicia, which could be considered an

[Page 39, Volume 2]

important Jewish cultural center, had to be asked with serious words by the officials in power to take an interest on behalf of its own and its fathers' faith. The correspondent emphasized that credit should be given to the then Tarnow kehila managing committee that “It instantly and energetically went to work.”

The correspondent appealed to the then head of the Tarnow kehila, Y. B. Goldman, that, “He not let himself be led off the path by various party schemes or other petty motives.” In addition, a separate warm thank you to Petri, the then director of the Kaiser Royal gymnasia [secondary school] in Tarnow, at whose initiative the entire matter was raised.

Tarnow Jews Want to Establish a German–Hebrew School

From a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in the Leipzig Algemeiner Zeitung des Judentums of the 21st of December 1858 (no. 52), we learn that about 500 Tarnow Jews signed a petition to the Jewish kehila [kehila = committee of elected officials managing Jewish affairs] with a request to establish a German–Hebrew school in Tarnow.

It is worthwhile to mention that these schools were strongly opposed by the Orthodox Jewish circle that also

|

|

| The Jewish hospital in Tarnow in 1939 |

[Page 40, Volume 2]

opposed this request from the enlightened Jews to create a secular school. This happened in the era when the Austrian reaction increased in strength and which had as its purpose the annulment of the achievements of the revolution of 1848.

The Jewish Hospital in Tarnow in 1860

Tarnow Jewry could already take pride in its social–communal institutions in the first half of the 19th century. Jewish Tarnow was especially proud of the Jewish Hospital that was erected in 1842 and in the course of later years grew into one of the best medical institutions in all of western Galicia.

In the previously mentioned newspaper article from Leipzig of the 24th of April 1860 (no. 17), an account was printed that the administration of the Jewish hospital in Tarnow had published [about its work] during the period of 1858–1859.

According to this report, in the course of the 17–year existence of the hospital, approximately 10,000 sick people were taken care of and, in addition, it is interesting that among 486 patients who were there under medical treatment were 12 Italian soldiers who were wounded in the Italian–Austrian War.

As was reported in the mentioned account, the rise of the Jewish hospital in Tarnow was possible thanks to the sacrificial work of the hospital managing committee of that year, to which belonged Chaim Leib Fajgenbaum, Yisroel Avraham Kaminer, Mendl Keller and Menka Weksler, in addition to the main doctor (prescriber), Dr. Yaacov Szicer, who simultaneously was the main doctor in the civilian Christian hospital. In the course of many years, he was active in these two hospitals, without harm to his private medical practice and without any reward. As a sign of respect on the part of the entire population, he was awarded the honored title of Freeman of the city of Tarnow.

[Page 41, Volume 2]

The City Managing Committee of Tarnow and its Demand to Recreate a Ghetto for the Jewish Residents

The first rays of civic and political equal rights appeared for the Jews in Galicia with the freedom movement in the Austrian state in 1848. The Polish mieszczanie [townspeople], whose representatives ruled on the managing committees of the Galician cities, aspired to maintain with all possible means the earlier limitations in regard to the Jewish population and when in Austria in the first years of the second half of the 19th century, the reaction returned to power, the local government organs in the cities and shtetlekh at once began to suppress the few equal rights the Jews had received in the era of the “people's spring.”

The Tarnow city managing committee was particularly distinguished in this area. As we learned from a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in the Leipzig Algemeiner Zeitung des Judentums of the 24th of April 1860 (no. 17), in the second half of 1858, the Tarnow city managing committee took as its responsibility the established privilege of 1764 of Polish King Stanislaw August that required the recreation of a Jewish ghetto in Tarnow. Hence, the representatives of the Jewish kehila in Tarnow undertook action against the attempt to annul the previously acquired right of the Tarnow Jews to live outside the ghetto area in the city. As a result of this attempt of the then Tarnow kehila–parnesim [elected Jewish community members], the county leader in a decree of the 8th of January 1859 ordered the Tarnow city managing committee to protect and to respect the civil rights of the Jews and not permit the disturbance of the current peaceful living together of the Jewish and Christian population of the city and that it not damage the development of the city, which was thanks in the greatest part to the commercial and industrial activity of the Jewish population.

The county leader added to this declaration, supporting the ministerial decree of the 13th of September 1858, where also at the order of the Galician national government of the 11th of October 1858, the active and passive voting rights to the city managing committee and to the municipal board could under the same legal conditions be obtained

[Page 42, Volume 2]

by the Jewish as by the Christian residents and in that connection the county leader made the Tarnow city managing committee aware that it was obligated to restrain itself from every principally negative attitude concerning this right.

The municipal organs of power in Tarnow had to give up their aspirations to recreate a Jewish ghetto in Tarnow in the second half of the 19th century.

Bloody Attacks on Jews in Tarnow in 1866

From time to time in the first tens of years in the second half of the 19th century, bloody excesses against the Jewish population took place in Tarnow.

From a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in the previously mentioned Leipzig Algemeiner Zeitung des Judentums of the 22nd of May 1866 (no. 22), we learn that on the 6th of May drunk recruits appeared on the road to the Jewish neighborhood in Tarnow, who called out, “Bić Żydów” [murder Jews]. Every Jew they encountered was bloodily beaten and robbed. At the same time, panic broke out in the Jewish neighborhood… Jews in great haste hammered shut the doors and shutters of the shops… closed the gates of the houses.

Alas, there were those who did not escape in time and close the shops… Not only were they murderously beaten by the bandit–like recruits, who came to the marketplace, all of their goods in the shops were stolen… With luck, several esteemed Christian citizens of the city persuaded the city leader that he should intervene with the local military commandant and to ask him to put an end to the violent actions of the hooligan attacks.

They did not have to ask the acting Austrian general for very long and as is reported in the above cited correspondence, he himself appeared in the Jewish neighborhood with a division of soldiers and sent out patrols, which drove away the mob and arrested the main attackers. They were punished in the presence of the general and

[Page 43, Volume 2]

military patrols guarded the streets of the city all night. Calm reigned the next day in the city.

*

We have written in detail about the bloody pogrom against the Jews in Tarnow in 1870 in the first volume of the Tarnow Yizkor Book (in the article about the history of the Jews in Tarnow).

Jewish Societies and Institutions in Tarnow in the Second Half of the 19th Century

The Bikur Cholim Society

In addition to the Jewish hospital in Tarnow, about which we wrote in the previous lines, in the second half of the 19th�century, a very useful activity developed with the establishment of the�Bikur Cholim�Society [Society for Care for the Sick], whose task was to give free medical help to the poor Jews as well as cover a part of the expenses for their medicines.

As we learned from a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in HaMagid [The Preacher] of the 22nd of January 1873, this society was founded in Tarnow in 1872 and in the month of January 1873 already had about 700 members who supported the activity of the society with all their possible strength. Devoted communal workers such as Reb Berish Maszler, Reb Pesakh Bibelman, Reb Shlomo Trinc, Reb Berl Dankowicz, Reb Avraham Klajnhendler and Reb Yisroel Mendl Keler belonged to the society's managing committee.

Noyse–haMita v Menakhmi baOylim

This society [of those who carry the dead on the mita or bed to the cemetery and the consolers of the mourners], which was very prominent in the Jewish neighborhood in Tarnow in the 1930s, has already been described in the first volume of the memorial book, Tarnow. It numbered 800 members in 1932 and had as its purpose supporting the poor and sick Jews by assisting them in moving the deceased from the house to the cemetery. This society was founded in Tarnow in 1891 and

[Page 44, Volume 2]

in time grew to be a very important social institution in the city.

As we learned from a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in HaMagid on the 10th of February 1893, this society opened a kitchen for the poor at the beginning of the year where everyone who “stuck out their hand” received a cup of tea and bread in the morning for one zloty (one Kreuzer – two pennies) and a bowl of soup and bread for two Kreuzer for lunch.

The work of this society on behalf of the poor strata of the Jewish population in Tarnow took on a very wide scope during the winter months. Until the month of March, every poor Jew received bread and coal for all seven days of the week. A great campaign to collect money from the rich middle class in the city was carried out every year for this purpose. This campaign was led by the then community activists, Skharye Mendl Aberdam, Ahron Safir, Mordekhai Dovid Brandsztatter, H. Hajman and occupied with distributing the bread and coal were Pesakh Bibelman, Shlomo Klajner, Pinkhus Moshe Goldwaser, Yosef haKohen [member of the priestly class] Ejzenberg. As was described in the previously mentioned correspondence, 1,200 loaves of bread and 600 kilograms [about 1,322 pounds] of coal were distributed during one week (in the month of February 1893).

As we see, the number of the poor in the Jewish neighborhood in Tarnow was not small.

The Great Aid Action by the Tarnow Jews on Behalf of the Jewish Community in the Neighboring Shtetl of Zabno After a Fire in 1888

On a Friday afternoon at the end of April 1888, a fire broke out in the neighboring town of Zabno near Tarnow, which engulfed the entire shtetl from one corner to the other. Almost all of the houses were burned and the entire Jewish population in the shtetl remained without a roof over its head. There also were human victims and as we learned from a correspondent from Tarnow in HaMagid of the 6th of May 1888 (no. 17), several Torah scrolls and rare religious books were burned. As the correspondent writes, on the same evening as the fire, Tarnow Jews sent bread to the fire victims in Zabno and on the next day, Shabbos, wagons of bread left for Zabno so that the Zabno Jews would not suffer from hunger.

[Page 45, Volume 2]

|

|

| Headstone of Reb Mordekhai Dovid Brandsztatter, of blessed memory, and his wife, Shprinca, of blessed memory |

An aid action on behalf of the Zabno Jews was simultaneously organized with the then leader of the kehila, Herman Merc, at the head.

F. Grosbard, the head of the Zabno kehila, issued an appeal at the conclusion of Shabbos [Sabbath], in which he described the sad situation of the Jewish population in the burned shtetl, where in addition to the fact that almost all of the residences were burned, no survivors remained of all of the houses of prayer with their Torah scrolls and treasure of holy books.

[Page 46, Volume 2]

The appeal ended with an impassioned call for immediate help for those in the Jewish community in Zabno who had suffered from the fire.

The Shavei Tzion Society in Tarnow in 1893

As we learned from a correspondence from Tarnow that was published in HaMagid on the 20th of October 1893 (no. 32), the Shavei Tzion Society [Returners to Zion] was founded there with the purpose of buying land in Eretz Yisroel and sending one of the members there from time to time; this fate fell upon around 100 members who decided to emigrate to Eretz Yisroel. The society first numbered forty members at its founding and the founders undertook a campaign to recruit members from other cities in Galicia.

The Jewish Community in Tarnow in 1897–98 and 1913–14

When writing the treatise, The History of the Jews in Tarnow, we did not have the opportunity to make use of a series of sources and information concerning the facts that have a connection to the history of the Jews in Tarnow and which we received later, after�the first Tarnow memorial book had already had been printed. The various information that we provide here are a significant contribution to the history of the Jews in Tarnow. We have taken it from a Calendar for Israelites, published by the former Austrian union, Austrian–Israelite Union in Vienna. In this calendar, published in the German language, we found facts about almost all of the Jewish kehila in the entire Austro–Hungarian monarchy.

Let us be permitted at this point to express a hearty thanks to the Tarnow landsleit [people from the same town] and Friend Chaim Keller, who today lives in Vienna with his esteemed wife and son and before the Holocaust occupied a distinguished place in the clothing industry in Tarnow and was among the active leaders of the local Mizrakhi [religious Zionists] movement, for his efforts and help in obtaining the above–mentioned calendars for several years.

The Tarnow kehila in the Budget Year 1897–98

The head of the kehila [organized Jewish community] at that time was Yosef Maszler and his representative was Ahron Safir. Avraham Aberdam, Mordekhai Dovid

[Page 47, Volume 2]

Brandsztatter, Borukh Jakubowicz, Yakov Maszler, Moshe Ornsztajn, Naftali Ruvin, Artur Szancer, Moshe Weksler, Hirsh Witmaier, Dovid Cinz belonged to the advisory council. The representative of the rabbinate was Naftali Rubin and the rabbinate's assessors were Naftali Goldberg, Moshe After, Shlomo Yosef Kurc, Yehuda Arszicer, Yoel Etinger. Yosef Ejzenberg, Shlomo Dovid Baran were at the head of the Chevra Kadisha [burial society] and Berish Maszler and Borukh Jakubowicz belonged to the managing committee of the Jewish hospital.

The Jewish kehila in Tarnow in the Budget Year 1913–14

Barely six years passed and the Jewish community in Tarnow had gone through a significant ascent. Close to the outbreak of the First World War, in the budget year of 1913–14, 17,000 souls were registered with the Tarnow kehila and there were 850 kehila taxpayers. Berish Maszler was then the head of the kehila and his representative was Eliyahu Baran. Yosef Maszler (the older one) and Leon Szwanenfeld belonged to the restricted kehila managing committee. Avraham Aberdam, Dr. Eliash Goldhamer, Yakov Geldwirt, Mordekhai Dovid Hercig, Mendl Hercbaum, Borukh Jakubowicz, Ignaci Maszler, Dr. Herman Pilcer, Dr. Edvard Rapaport, Herman Soldinger, Yoel Szpigel, Dr. Shlomo Febus, Lazar Szpira, Ayzyk Safir, Avraham Tarn, Dovid Cinz belonged to the comprehensive managing committee. Reb Avraham Abela Sznur was the city rabbi. kehila secretary: L. Lerhaupt. There were Jewish societies active then in Tarnow: Noyse–haMita [society of those who carry the dead from the house to the cemetery], Yad HaRutsim [Orthodox workers organization], Mishnius [Society for studying the Torah], Kiddushin [Torah innovations], Rodfei Tzedek [Pursuers of Justice], Chevra Yoledet [society to help pregnant women] and Kallah� [society to assist poor brides]. It was also mentioned in the previously cited calendar for this budget year that 40 prayer groups [minyonim] existed in Tarnow.

A Rabbinical Conference in Tarnow in 1927

For the voting to the third Sejm [Polish parliament], which took place in 1928, the National Union of the Zionist Party in western Galicia joined the Zionist National Union in eastern Galicia and both proposed a joint list [of candidates] under the name, the Unification of Jewish Parties in Lesser Poland [historical area with Krakow as its capital], when a minority bloc was organized in Congress Poland which encompassed only some of those from the non–Jewish and also from the Jewish national minority. In addition to the two blocs, another was created,

[Page 48, Volume 2]

|

|

| Headstone of Reb Yoakhim Maszler, of blessed memory – member of the kehila managing committee in Tarnow in 1897–98 |

the third election unification of the Folkists and the Orthodox Agudah in the Jewish neighborhood.

An independent Jewish policy was one of the main slogans of all three groups.

Taking a stand for this election were also the camp of the

[Page 49, Volume 2]

Galicianer rabbis, who fought all Jewish national movements, even those in agreement with Agudah [organization founded by Orthodox rabbis].

|

|

| Headstone of Reb Artur Szancer, of blessed memory – member of the kehila – the managing committee in Tarnow in 1897–98 |

As Dr. Yitzhak Szwarcbard writes in his book, Tsvishn Beyde Velt–Milkhomus [Between the Two World Wars], (page 230) – 35 rabbis held a conference in Tarnow on the 5th of December 1927 and 281 rabbis were called again to a similar conference

[Page 50, Volume 2]

|

|

[On the right is] the headstone of Dr. Herman Pilcer, of blessed memory,

and his wife Lucia – [he] was a member of the kehila [organized Jewish community] managing committee in Tarnow in 1913–14.

[On the left is] the headstone of Dr. Shlomo Merc, of blessed memory –

court council and member of the city council in Tarnow until the outbreak of the First World War. |

in Lemberg on the 27th of December 1927 and a policy of supporting the government without conditions was declared at both conferences.

These two rabbinical conferences also are mentioned in the collection, Di Yidn in Videraufgeshtanenem Poyln [The Jews in Newly Reconstituted Poland], edited by Dr. Yitzhak Sziper, Dr. A. Tartakower and Aleksander Haptka (p. 11), in which is described the decision on the resolution that was adopted at the conference in Tarnow, in which it was clearly emphasized that “The conference speaks out against actions which are not in accord with the wishes of the [government] authority because it is our duty to carry out a policy of loyalty to the government.”

This policy– as reported by A. Haftka in the cited collection – was confirmed at the conference of the 281 rabbis in Lemberg on the 27th of December 1927.

Novi Dziennik [New Daily Paper] from Krakow from the 11th of December 1927 (no. 328) also published the news about this rabbinical conference, where it was reported that a meeting of some 20 rabbis from eastern and western Lesser Poland took place in the residence of Reb Leyzer Lezerin of Tarnow on the 5th of December 1927 about an agreement concerning the elections. According to this information,

[Page 51, Volume 2]

|

|

|

|

Headstone of Reb Ayzyk Safir, may his memory be blessed –

member of the kehila managing committee in Tarnow in the years 1913–14.

On the right (the X mark) a memorial tablet to the memory of his wife, Klara,

may her memory be blessed, perished in the Tarnow ghetto in 1942. |

|

Headstone of the Tarnow city rabbi before the First World War, Reb Avraham Abela Shneur, may the memory of a righteous man be blessed |

the chairmanship of the convention was held by the rabbi from Krakow and the conference unanimously declared itself against the spread of the Pilsudski decree concerning democratic elections to the kehila [organized Jewish community].

On another day – the 12th of December 1912 – a retraction was published in Novi Dziennik (no. 329) that reported that the Tarnow rabbinical conference did not have any connection to election matters because, in general, elections were not debated and resolutions were not adopted there [at the conference] and the conference had been called only to consult about creating a union of rabbis in Lesser Poland. In addition, on the 27th of December 1927, it was decided to call a separate conference in Lemberg about this matter [a union of rabbis].

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Tarnow, Poland

Tarnow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 4 Nov 2022 by NB