[Page 240]

The Orphanages and the Boarding house

by Rosa Berliner

Translation by Naomi Gal

The Joint whose leaders were dealing with the orphans' problems and took care of them continued to support the orphanages even after a group of children were sent from the orphanages to Eretz Yisroel and other countries. They acted through committees of local activists, in Rovno and elsewhere. These committees prompted to action different institutions and individuals. A special concern was training the children for different professions, in order to prepare them for independent life, and the diverse advocates who were part of the committees contributed to this training project. For this purpose, an association was created in Volhynia to take care of abandoned children, an association that later became a branch of Warsaw's Center.

In Volhynia, the first committees' conference held on January 16–17, 1923 in Rovno, with the participation of 93 delegates from 62 settlements responsible for orphans (actually, back then the Joint handled 2600 orphans in Volhynia, scattered in 95 settlements, and in addition there were about 600 orphans in other institutions). In the conference, the Joint representative demanded that the committees take responsibility for the orphans and support the orphanages, since the Joint was about to cancel its operations in Poland. Many of the advocates hesitated and opposed the demand, but Rovno's delegates and other cities delegates understood the situation – and the Joint suggestion was accepted. In that conference a central committee for Volhynia was elected of 17 members and out of them an executive committee of 5 members: Hakel Weitz, Eliyahu Lerner, Laybish Harif, A. Goldin and Avraham Dannenberg, as a director – Shmuel Shrier.

The Joint's orphans' department continued to function until March that year. When the executive committee was about to begin its role, it found out that the new institution was illegal (until then the authorities did not certify any public institution). Attorney Rapaport was summoned to handle the case, and a delegation, with the lawyer, presented themselves in front of the regional authorities in Lutsk – and succeeded. On July 8, 1923 a permit was granted to the association for helping Jewish orphans. The certified association applied to the local authorities requiring regular sums of money to help the orphans and sent a circular to the communities and the magistrates asking them to include in their budgets a clause supporting Jewish orphanages. This worked out well, and since that time, a new era began of helping orphans in Rovno.

Shortly after, the Joint liquidated all its activities, and so, the burden of taking care of orphanages and individual orphans, who were in institutions or with families, was transferred to Volhynia's Center and the local associations, representing the public in every location. As part of the change that took place in Poland, especially with assisting orphans, a new organization was founded in Warsaw, replacing the center that existed during the Joint era – a union of the associations aiding orphans and this center directed and managed all actions. The number of orphans in Rovno, who were under the association's care, was then around one hundred; some were in orphanages and others in private homes under the association's supervision. Most of these children studied in Talmud Torah, some of them in Hebrew schools, and a few in General Polish schools, the rest in Yiddish schools and in Ort School. The budget to maintain all these orphans was quite substantial and the sources of support were: the

[Page 241]

allocations of the magistrate and the community, donations and contributions of the city's Jews and the center's aid. Expenses were always greater than the income and the deficit grew from year to year. One of the positive activities of the association was sending the children in the summer to special summer–camps; the benefit of this feat was great, but it was very expensive.

Between 1922 to 1923 there were two institutions for Rovno's orphans: one was an orphanage for young children, age 3 to 10, it hosted about 60 children and the other one was a boarding school (that was called “Internat”) for orphans 10 years and older, where about 40 children were educated till they were independent or left Rovno. The orphanage was sustained mainly by local allocations and donations and its budget was hardly covered, while the boarding school was maintained mainly by Warsaw's Center. These two institutions differed in their structure and budgets, but both had the same goal and managing them was done with full responsibility by those who headed them. The permanent workers in these institutions knew their role and fulfilled it with dedication and love in all areas, as all those who were close to the endeavor of taking care of the orphans during the Polish Regime in the city can testify. Another proof were the many students who graduated from these institutions and found their place in Israel or America, holding in their hearts warm memories from their days in the orphanage and the boarding school.

One of the deficiencies in Rovno's orphans' institutions was the lack of appropriate and comfortable apartments. But the heads of the project took action and with the help of Rovno's entrepreneurs and the Center, a building surrounded by a garden was purchased for both establishments on Litovsky Street, a printing–house was installed so that the orphans could learn a profession, the offices were there too, as well as other services. Once the building was bought, better conditions were created for the children and the staff,

Most of the time the boarding school children were sent to Ort School to acquire a profession and general studies, but some were sent to different tradesmen: carpenters, metalworkers, photographers, dental–technicians and others, so that they were able to work as apprentices and learn the job. These children also frequented the Hebrew and Polish schools. Beside the printing house there was a sewing–salon in the boardinghouse, where girls could work after learning sewing in Ort and many of the city's women used this salon for their clothes.

In the large hall of the boardinghouse they held parties and receptions for VIP's who visited Rovno (remembered are the visits of Bialik, Bistritzky, Leib Yaffe and others). Mrs. Rosa Gofman was the boarding school principal and was gifted and dedicated. By her side was Mrs. Bilhah Shmoshky, who was a teacher at the sewing workshop. The writer of these words was for eleven years the chairperson of these institutions while serving as a member of Volhynia's Central Committee and its representative in Warsaw's Center (from 1924 till her Aliya in 1934). Mrs. Rachel Trovatz and Mrs. Tudros were active during fund–raisers and Leib Spielberg, the chairman of the Central Committee for Orphans, was also extremely helpful.

We can read about the process of helping the orphans in 1934 in “Unzer Wag”, issue No. 2, January 26, 1935:

“On January 19, 1935 a general meeting was held by the association in charge of the orphans. Mr. Eliyahu Lerner, the meeting's chairman, Mr. Konivsky the secretary, and the director Matityahu Shlif gave a report of the last four years. The deficit that was in 1929

[Page 242]

8360 goldens grew by 1800 goldens and is now 10160 goldens. The reason: poor economic situation in the city that disables most Jews to contribute donations, a decrease of the magistrate's allocation and not increasing the community's budget. He criticized Warsaw's attitude, which allocates only meager sum for Rovno, he demanded from all of them to make an effort, cover the deficit and insure the budget in the future. When speaking about the institution's situation he related that the association maintains and supports 56 orphans (29 boys and 27 girls) and in the last four years 23 grown children left the orphanage and found work, five are in Kibbutz and training there. The educational plan is working well, as so does the medical and hygienic assistance, food and clothing are guaranteed for the children, the management and the staff dedicate as much as they can to the children and the institution. The public attitude is positive and everybody should be proud for the great achievement.

Zibes, representing the supervision committee, announced that the association's balance was checked and certified.

The members of the management added to the report and stressed that the public must help the abandoned orphan, and that a big city like Rovno should serve as an example to other cities. And indeed, the accounts given, clearly demonstrated the important and blessed enterprise performed with dedication under harsh circumstances and growing deficit.”

The graduates of Rovno's orphanage who made Aliya speak profusely about the warm and dedicated treatment they received during the years they spent in the orphanage, and about the education and training they got from the association and its staff before coming to Israel. They mention fondly the head advocates: Mrs. Perlmutter, Mrs. Stock, Mrs. Berliner (Raidel), Mrs. Salzman, Mrs. Sandberg, Mr. Shrier, Mr. Dannenberg, Mr. Itzhak Berliner, Leib Spielberg, Matityahu Shlif, Benzion Eisenberg, Nhas, Lerner, Ides and others.

I was a Boarding School Student

by Mina Stir (Shemesh)

Translation by Naomi Gal

I was a student in Rovno's boarding school orphanage. I grew up in this institution and learned there Torah and good–manners, and had many ties to it, to my friends with whom I lived, to its administration and to all Rovno Jews. The name “Internat” (that is how they called the boarding school) is engraved deep in my memory and I will never forget the many experiences I had in this time of my life.

I was about four–years–old when my father Pinhas and my mother Rosa Shemesh were murdered by the Bellachovtzimas rioters in their village Opala near Lubemill. As an orphan I was taken back then, in 1920 to Faige Lifshitz, my cousin's house in Lubemill. My relatives surrounded me with concern and warmth, but the dire economic situation that prevailed after the war prevented my family from supporting me. When I was in Lubemill I began my studies in the Hebrew school with Palevessky as principal, and also in the local Polish school, I did well in my studies.

[Page 243]

In those days an assistance committee was organized in Lubemill to help orphans. The old activist R' Avraham Shientop (they called him Avrem'che Tirashkes) showed an interest in my situation as a forlorn and bereaved child, separated from my nearest, and he wrote the center for orphans in Rovno, Volhynia and as a result I was accepted to the boarding school there and so, after four difficult years in the village, I was sent to Rovno. No one accompanied me, all alone with a sack that contained my few belongings, I arrived at big Rovno's train–station and in a carriage led by a horse the horseman led me to Litovsky Street, directly to the Boardinghouse, with the letter R' Avraham Shientop gave me.

From the first day people welcomed me at the boarding school, I was docile and acclimated fast. Despite my young age I knew my place and understood my situation. In the new environment I found a circle of children whose fate was as cruel as mine, and we played, worked and studied together and I was on good terms with all. The caregivers, the guides, the principal, the activists and the teachers were generally good to the children, as if they wanted to give us what we were missing and the Internat became for me more than a home: my family. We were back then nine boys and twenty–three girls from different locations.

In my first year in the boarding school I was sent to Ort School. During the day I learned sewing and, in the evenings, I studied general studies. I was educated and made progress. Every cloud that surfaced in my life's sky was challenged and repressed by me, I felt the need to be independent, prepared for life, since I had no one to lean on. On my second year I joined with some of my friends Hashomer–Hatzair Lodge and was very interested in its activities. I was already dreaming about Eretz Yisroel and my future life there. But something happened that led me in other directions.

In our boarding school there was a girl from Kovel. When I befriended her, I discovered the existence of my uncle, my father's brother, in Argentina. I researched and found his address and contacted him. The uncle, who did not know about me, was very glad and immediately wanted me to come over. I was overwhelmed, I loved the boarding school and my friends and I felt bad leaving them, but I responded to my uncle's summoning. And so, after five years in the institution I traveled to my uncle in Argentina.

A new world was revealed to me in faraway Argentina. I was about 16–17, and the good uncle and his family showered me with love. I began studying, but after a short while I became part of a family life.

In my time there were several advocates who worked for the boarding school and I remember them well: Mrs. Rosa Berliner, who guarded the institution and was concerned about each child in the boarding school; Mr. Leib Spielberg, one of the heads, who was like a father and brother to us and always responded to us when needed; Mr. Hahas, one of the staff and others. Remembered fondly is our kind principal Mrs. Rosa Markovna Gofman, who was like a mother to us and we were very attached to her. Already then – in our childish mind – we were able to appreciate all of them, and I remain forever deeply grateful to them.

[Page 244]

Memories of the Orphanage Student

by Ephraim Ben–Shmuel

Translation by Naomi Gal

The name Rovno evokes warm feelings in the heart of a man whose fate connected him to this city in his early childhood. Rovno – an echo from days–by–gone that are unforgettable. Many are the feelings accompanying this man who is grateful to this Jewish City for all it gave him in his first steps in life.

I was born in 1912 in the tiny village Korman, near Zhytomyr, to my father Shmuel and my mother Rachel Slipak. When my mother died my father married a second wife who bore him a son and after a few years he too died. I remained orphaned from both my parents, almost abandoned during World War One, until my stepmother found a way to send me away and I was taken to Rovno's orphanage in 1920. I was just eight–years–old and I already knew suffering. But then I found at the orphanage a ray of light in my loneliness. In this institution I felt warmth, which I was sorely missing, a caring hand and concerned heart, a wish to provide me, as to other children in the establishment, what a child has under his parents' wings. This hand was Rovno's Jews' hand, which I will never forget. In this home I stopped seeing myself as wretched, the atmosphere was fatherly and motherly, and I felt the same way when I was accepted to Tarbut Hebrew School. Like all other children, I knew for sure in my childlike innocence, that the institution and those working in it as caregivers, guides, teachers and entrepreneurs are saving me and my friends from atrophying. We had lodging, food, clothes, shoes, we were taken care of and educated so that we would have a future.

When we grew up and perceived the problems and worries of the institution's administration concerning means to maintain it – although Rovno's Jews gave generously to the orphanage – our gratitude increased to this home and to all the city's Jews, who symbolized for us our people's values, the Jewish heart and the mutual responsibility of Israel's sons to their brothers. We, the children, who all lived together under the same roof and under the same conditions, knew how to handle our younger brothers as a brother treats his brother, and we formed one peaceful family. We wanted to alleviate our educators burden, although we did not know the secret of their difficulties. On Shabbat and holydays, an ambiance of joy and light, in addition to the light in our hearts, inundated the house. The children were dressed up, sparkling clean and healthy and we prayed together and spent the holy day spiritually uplifted.

The institution planted in our hearts an affection for the nation and its values, we learned to be proud Jews and loyal sons to the people and Israel. The Hebrew education in Tarbut and Talmud Torah schools provided us with Torah, knowledge and good–manners. Many of us joined youth movements and were even prominent among their members. The establishment made sure we learned a profession so that we could become independent.

Thus, the orphanage was maintained and sustained in Rovno for many years, since then, in 1920, the first orphans were sent to Eretz Yisroel, America and Argentina. There were different classes, not according to a plan, since some left and other arrived. When I was at the orphanage from 1920–1929 the girls learned sewing and the boys were sent to different workshops to learn professions and train in them; most of them succeeded, and with time became financially independent. But even then, they were not abandoned by the administration and the advocates – the connection between them was not severed.

[Page 245]

In the beginning the orphanage was in Plotnik House and then at the end of Afrikanska Street, till they purchased, with donations' help, a special building close to “Gorky” where there were many facilities for the students and the staff. This is where we grew up and from there we went to the wide world and made Aliya in the thirties.

But then a grave turning–point arrived: extinction descended on Rovno and its Jews; distraction, annihilation and devastation fell upon the city's Jews by the hand of the Nazis and with them were exterminated many of our friends who were at the orphanage. From Miriam Harash, one of the orphanage inhabitants, we found out that in 1940 the Russians transferred the orphanage to Ostrava and from there to inner–Russia. A large number of the orphans died in the Typhus epidemic that erupted among them, some of them dispersed, and some luckily arrived after the war to Israel.

With the Poets H.N. Bialik and S. Tchernichovsky

(Some memories)

by Ester Wiener–Ben–Meir

Translation by Naomi Gal

It was in spring of 1928 and I was then a student in the 6th grade of Tarbut Gymnasium. One day we were told that the poet Shaul Tchernichovsly is about to visit Rovno. I was then deeply impressed by his poems that Mr. M. Gilerter, our literature's teacher, read to us during the last classes, and I waited impatiently to see a great Hebrew poet with my own eyes. I begged my parents for us to go to the train station and welcome him. It was evening, and in the station many people were already gathered, representatives of Zionist organizations and youth movements, and this crowd swallowed Tchernichovsky, so that I could hardly see him, till they put him in a carriage and drove him to town. My consolation was that I would see him the next day in the gymnasium.

The next day I was early at school. When I entered the post street alley I saw lots of commotion: the yard was decorated with flags, a stage was erected and an honor–gate was installed at the entrance. We stood like soldiers while our hearts beat loudly, anticipating the approaching poet. We received the order: Eyes to the left! And we cried three times: “Be Strong and Good of Courage!”. Little girls handed the visitor flowers. He climbed the stage with his escorts. The principal Dr. Rise and Mr. Gilerter gave welcoming speeches. Suddenly it started to rain. We congregated inside the building, and it was there that the poet addressed us. I was charmed by his looks: his kindness was spread over his face and his cheerfulness was apparent. He spoke about: “The Sun as the Source of Life and Creation”. He tried to amuse us saying that his poems “are trouble–makers” – since sometimes one gets bad grades…

In the evening an event was held to honor him in Zafran Theatre. I sat with my parents in one of the booths. The hall was packed. There are no words to describe the celebratory atmosphere that reigned among the audience. Amid them there were people who were usually distanced from nationalism and alienated to Hebrew Culture. Non–Jews were there as well – the “Curatorium” (Education Department) people. I do not remember all the speakers that evening, but I was impressed

[Page 246]

|

|

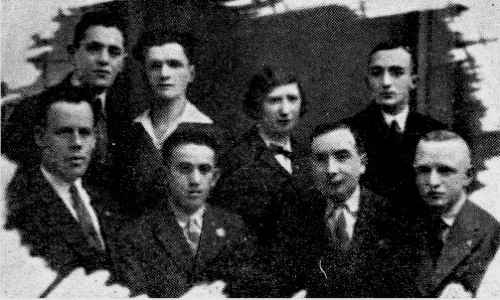

A party in honor of Shaul Tchernichovsky in Fissyook House

Sitting (from right): Teacher Weinstein, Dr. Issachar Rise, Mrs. Shulamite Fissyook, the poet Shaul Tchernichovsky, Shmuel Rosenhak and Itzhak Barkovsky

Standing (from right): Sevitzky, Shmuel Fissyook, Mrs. Rachel Fissyook, Alexander Shtrik, Menahem Gilerter, the boy – Moshe Shtrik |

especially by one detail: the teacher Itzhak Barkovsky gave an in–depth and detailed lecture on the poet's work. Tchernichovsky approached the stage close to the end of the lecture and said a few words about one of the technical elements of poetry (onomatope) and at once demonstrated by reciting his poem: “…Night…Night… Night of idols…” we were all charmed. A feeling was born in me that no “scientific” or “practical” analyzing of poetry can clarify it better than reciting the poem itself.

In the second part of the evening students recited some of Tchernichovsky's poems. Finally, we the students, climbed the stage, but the poet was tired and retired.

The next day Tchernichovsky visited us in class. He entered accompanied by Mr. Rosenak. We were studying Isaiah. He set on a bench like one of the students and listened. The teacher singled the students' who excelled in Hebrew and the poet engaged in a conversation with them, read their compositions and encouraged them.

In the evening we held a welcome to the poet in the square of “Hashomer–Hatzair”. His eyes were full of joy watching the young scouts and the “Old” Shomrim. Mr. Weinstein, the teacher, welcomed him as did Simcha Orbuch, the Lodge's head. He departed with warm greetings.

The days that followed seemed rather gray. The teachers felt that after the high–tension it will not be easy to go back to normal routine, so each one of them added a detail about Tchernichovsky's personality. One said that he introduced Europeans ‘influence to our literature, and that is why he is close to those who had European education; another one defended his “Hebrew–ness”. We were surprised to learn that by profession he was a physician and that aside from his gift he is a great scholar, speaks many languages, and is busy day and night with his studies.

I was very envious of our gymnasium's graduates that year who were lucky enough to have Tchernichovsky's picture engraved forever in their year–book. I was consoled by the thought that before I graduate Bialik would visit us…

And indeed, Bialik arrived, but only four years later and I was by then in twelfth–grade but in another gymnasium, “Oshvieta”, which was previously named: “Pelska–Jidovska”. After

[Page 247]

I graduated from Tarbut Gymnasium I wanted a “recognized” governmental baccalaureate so I entered, with three other Tarbut's graduates, for one year to a Jewish–Polish Gymnasium that had “privileges”. We were not happy there that year, first of all because we already graduated from twelfth–grade and secondly, we missed the atmosphere we were used to in Tarbut. And then Bialik arrived. We were informed that from each class a delegation of only three would welcome the poet in the rail–station. When the home–room teacher addressed the class and asked us to nominate the candidates, all four of us stood up. We were embarrassed: we did not represent them, but they understood that no force would stop us from going to the train–station. We went. We were all very bitter, especially when we found on the field in front of the station our entire gymnasium, with all its students, teachers and its flag, while the gymnasium we were unwillingly representing, sent only a delegation, with no flag. Sadness ate at us. Then the poet passed along the lines of Tarbut's students and greeted them, but then he approached us. We were accompanied by the old Hebrew teacher of that gymnasium, Mr. Bergman. Bialik knew Bergman, probably since childhood, and he was excited to meet him and even kissed our old–man on his lips…that was for me a kind of consolation…

There were two rallies with the poet: one was for the elementary schools and Tarbut Gymnasium and the second for the other Jewish Gymnasiums and the Jewish students of the governmental Polish Gymnasium. And again heartaches: I arrived to the other rally with our class and here Bialik spoke Yiddish. Maybe due to my bad–mood I was at first unimpressed by the poet and his words. I was almost indifferent. I remembered the curly hair of Tchernichovsky, his young fiery eyes, and here I saw a homely looking man, with a golden chain on his vest, standing and speaking in Yiddish…I listened reluctantly. But all of a sudden, a miracle happened: Bialik told us simply about pioneers who are building a home in Eretz Yisroel. They work feverishly, because they have to finish before sunset. And indeed, they manage. He described the enthusiasm of the pioneers, standing on the roof, lighted by the last rays of sun, and he himself got into such a “transport” of passion telling the story, that I no longer saw the bald man, not even his golden chain, and instead I imagined one of the visionaries that were in ancient Israel and who, as I learned, were gone once the people were exiled from their land.

[Page 248]

I did not regret coming to this rally anymore, which was intended for Jewish youth, that for the moment – most of them – were unable to read and understand Bialik's poems in their original language. I knew he captivated their hearts, and that sooner or later these young men and women would get acquainted with his Hebrew poems, and learn the language of this great national poet – their own language.

When the Youth Volunteered

(Some memories from olden–days)

by Zipporah Hampel

Translation by Naomi Gal

Rovno's Hebrew youth was famous for its loyalty and dedication to the Zionist Idea and for its activity in all areas of our public and national life. The prestige of our community as Zionist spread all over Poland, famous for its large contribution in building our land and renewing our language. All Rovno's Eretz Yisroel fund–raisers were successful and the Hebrew our youth spoke was known in all the state.

Tarbut Schools in our mother–city were short of space since so many wanted to join, but due to financial problems we were unable to expand our education net. Hence, many young men and women had to turn to other educational–institutions, where the national spirit was foreign. We were afraid to lose these youngsters, so there was abundance of secret activity and we widened our influence on the students in non–Hebrew schools. To each such school we infiltrated a few members through whom we promoted Zionist publicity and propaganda and this bore fruits: many were attracted to us and joined the ranks of the different youth movements that encompassed the many Zionist ideals and views that Rovno was blessed with. They began preparing themselves for lives of work, learning Hebrew, wishing to fulfill their vision of making Aliya even by harsh routes, sometimes without their parents' blessing who were lamenting their children on their way to unknown–country…

We, the remains of Rovno's youth who are in Israel, can tell about these glorious days, when immersed in wishes and vocations that captured our hearts – we were like dreamers. And we are so sorry, sorry that the multitude of brothers who did not follow us were lost in such a horrible and tragic way.

At this very moment, I can hear the sounds of the Hebrew language echoing, not only between the walls of the schools and the youth lodges, but in the city's streets as well. Our passion for Hebrew had no limits, and to elevate it we decided in our innocence to publicly show it off even in a non–Jewish environment. Groups of ours often appeared among the Christian population speaking loudly in Hebrew. Passers–by of our people, who were immersed in livelihood worries, used to linger for a moment and savor hearing the “Holy Language” spoken by the youth; as opposed to the anti–Semite Poles who were angered by the Hebrew and sometimes reprimanded: “Yid, go to Palestine”, but to spite them we continued to speak Hebrew in loud voices. We did this all year long, and especially on Sundays, which was a general holiday according to the state law and the streets were full of celebrating people, wandering around.

[Page 249]

Maybe it is worth to tell a story that took place. An old missionary, who was named by all: “Diedyushka Moysay” obtained a place in Rovno aiming to acquire souls for the man–from–Nazareth's ideas. There was an assumption that this missionary came from Jewish origins, who left his roots for greed. He opened a club in Rovno with the authorities' support, who obviously treated him well he used to invite people from our religion, seduce them with deceitful language and give them New Testament books for free. When I brought home this kind of bible my father became suspicious, checked the book, but found no harm. Father ignored what was written on the front page, that was formulated by “a wise man”, a name that did not sound Jewish.

There were some youth who began frequenting without thinking this missionary club, whether it be due to curiosity or for fun. The missionary lectured them about religious questions and thought–provoking dilemmas, and one had to admit that he was quite knowledgeable of Torah and Talmud. This was unpleasant to us. Afraid that innocents would be trapped in this inciter's net, we decided to save the day and intercept the missionary schemes. We began frequenting the club on a regular basis, aiming to annoy and disturb the instigator in all kinds of ways and ruses. At first the missionary was happy with our visits, believing that his theories were finding an audience, supposedly, but soon he found out he was wrong. We used to sit among the others and listen carefully, but as soon as the lecture was over we began showering the lecturer with many and different questions that confused him, and he did not know how to respond and satisfy us. Furthermore, we also provoked him, using all kinds of mischievousness and naughtiness to annoy and irritate him, to embitter his life and disgust his listeners until he left town. And indeed, our actions bore fruit: the club had fewer and fewer visitors, and it seemed that not one Jew was harmed nor influenced by the instigator or followed him. The youth, who previously frequented the club, were now brought under our cultural and Zionist influence, merged with us, and many of them made Aliya.

The Union of Jewish Academics

by Ze'ev Shatz

Translation by Naomi Gal

The graduates of Rovno's high schools who continued their studies in higher education schools were united under the name “The Union of Rovno's Jewish Academics”. The basis of this union was formed at the end of the twenties and a special charter was formed by its founders: Paytel, brothers Tefer, Izik Zam, Yosef Shohat, Yosef Shenkar, Nathan Heresh, Koifman and others.

The members of the union belonged to different movements, but it did not prevent them from being united as students in one union serving students who needed advice and guidance, and to maintain mutual assistance among themselves.

During the thirties the union had about one hundred and twenty members. Some of these students studied in Poland, meaning they could be accepted to higher education schools in Warsaw, Lvov, Krakow and Vilna, despite the limitations and the quota, and many other of the students studied in Czechoslovakia, Eretz Yisroel, France and Italy.

The union was active all year long, but during breaks, when the students used to

[Page 250]

come home, it was particularly active. They used to organize balls and public lectures in the Zionist “Beit–Ha'am”, in the gymnasium's halls and in the “Civil Club”, in the spirit of most members who were immersed in national consciousness. The members did not lose touch with the union even after they graduated and acquired a profession.

A number of Zionist advocates were part of the union that with time took an important role in the Zionist movement abroad and later in Israel. Many of them settled in Israel.

Particularly important was the influence of the union on assimilated students, who were brought up by assimilated parents and graduated from a governmental school. The union brought them closer to their roots – the Jewish People, and with time, to the Zionist Idea as well. Izik Zam should be fondly remembered for with his fiery talk and his persuasive talent was able to bring those who seemed remote closer to the Zionist Idea.

Among the union's activists in the last years before the destruction of Rovno were the committee members: Israel Gasko, Fania Krushinski, Mira Feferman, Julius Philipovsky, Ze'ev Shatz, Marmor Moshe, Gutman Lucia and other.

The Foundation of Maccabee

by Michael Dror (Daitshman)

Translation by Naomi Gal

The famous saying: “a healthy soul in a healthy body” resonated with many of the Jewish–National Youth in Russia and in 1912–1913 a youth association for sport and gymnastics was organized in Lodz, which was later named: Maccabee. Others learned from this association and after a year or two other Maccabee Associations were founded in different cities in Russia. These associations attracted young Jewish men and women, who performed under its flag and dedicated themselves to sport, which was considered by the Zionists as a “National Sport”. And indeed, these associations were Zionists and their flag was the Zionist blue–and–white flag, and their members' uniforms were white with added blue.

|

|

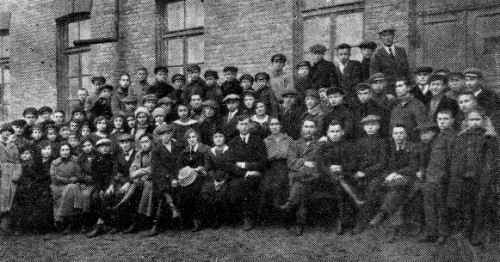

The Committee and Maccabee Members – 1920 |

[Page 251]

The sport was of high standard in Odessa and its Maccabee was famous among the different sport associations. The association was created at the end of 1913 and soon after in this beach–city Maccabee's Center was founded; it trained coaches for the branches, sent them instructions and connected them

|

|

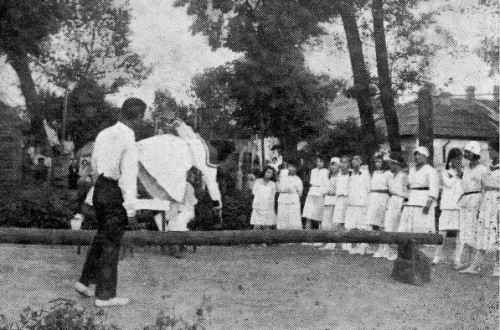

A group of Maccabee Women training – 1920 |

|

|

Rovno's Maccabee Members – 1920 |

in one framework. The head of the center and the local branch was then Yaakov Granovsky, an athlete and Zionist, passionate and idealist, who was the driving force of Maccabee.

While World War One was raging and many Maccabee members were drafted into the Russian Army – Maccabee Association continued to exist, although they were not very active but still planning for the future, and some of them evolved, despite the dire circumstances (in all of Russia there were then approximately 3000 members in 40–50 associations). The members practiced drilling exercises, played basketball, all kinds of other games, studied Hebrew and educated their friends in Zionism.

In 1915 I studied in Odessa and took a military course for instructors. When I finished the course, with hundreds other youngsters, I was sent to Rovno, a Rovno native, to serve as a Maccabee coach. In 1916, when I arrived in Rovno, I found a Sport Association called “Sokol”. I approached this association and found there Buzy Gorinstein, Siuma Gimberg, Shimon Rotenberg, Itzhak Gorinstein, Kanijer, Kopilnik and some others. When I realized that most of the members were Jews (there was only one non–Jew in the association, his name was Sasha) I begun promoting and working on organizing a Maccabee Branch in Rovno. My suggestion was accepted and a small group of Sokol members numbering eight to nine (Shimon Rotenberg, Akiva Shulman, Itzhak Gorinstein, Buzy Gorinstein, myself and others from Histadrut Association), became the base of the local Maccabee. I was charged with organizing and indeed, was able in a month or two to execute the idea and transfer almost all Sokol Members to Maccabee. In the soccer section

|

|

The Regional committee of Volhynia's Maccabee – 1931

Standing (from right): Avraham Rise, David Parchook, Meir Gilerman

Sitting (from right): Eliyahu Lerner, Dr. Alexander Rosenfeld, Avraham Zam |

[Page 253]

|

|

The participants in Volhynia course for coaches in Rovno – 1932 |

organized as soon as Maccabee was founded in Rovno, there were two teams: A and B; in addition, there was a group of teens aged 13–14 (who later became Maccabee members).

The first performance of Maccabee was in the Blue–and–White Ball the association held under the local Zionist Association at Zafran Theatre. Maccabee members appeared in blue and white national outfits, performed some exercises on the stage and charmed the audience. The ball was successful and served as a Zionist and sportive propaganda at the same time. Afterwards, many youngsters joined Maccabee and by the same token Zionism, especially from the circles of students in town. Maccabee took root in Rovno and excelled in most of its performances. It became especially prominent during the twenties when the Poles ruled Rovno, despite the obstacles strewn in its way. Even when some of Maccabee's activists left Rovno and others made Aliya, the association went on growing until it moved under Hasmonean's flag.

Sport Associations

by Avraham Rise

Translation by Naomi Gal

In March 1917, with the Russian Revolution, when diverse political and national activities began spreading among the Jewish population, sport had an important place amid other social initiatives of different circles. The Jewish youth, shaking away the oppression it was under, found in sport the best expression for its pride and spiritual healing. This was obvious in Rovno, too. The youth and school students saw

[Page 254]

in the Body Culture a vital part of their general and national evolvement. The heads of the student Zionist Association in Rovno: Yosef Bookimer, Asher Bernstein, B. Gaiviner, I. Gramfler, Ze'ev Zied (Meshi) and others took it upon themselves to organize Rovno's youth in sport areas as well.

Michael Daitshman, a Rovno native, who studied in Odessa and was there a member of Maccabee was summoned by Histadrut Committee to organize a sport association in Rovno, and he obliged. He withdrew members from Sokol and Histadrut Associations to the early Jewish Sport Association (amid them were David Teitelbaum, Akiva Gilbord, B. Gorinstein, D. Gimberg and others), and so, in 1917, a Maccabee Association was founded in Rovno.

When Maccabee was established in the city, many begun joining and the number of its members grew constantly. The sport activities, the exercises, the performances, the outfit – together with the conversations – attracted the boys and girls and brought them closer to the national movement while belonging to a national sport organization. In its beginnings, Maccabee dealt mainly with gymnastics, soccer and tennis.

In the beginning of 1920 David Skavirsky, a gifted athlete, arrived at Rovno after being in Kiev's Maccabee. Rovno's Maccabee seized the opportunity and nominated Skavirsky as a head coach in the gymnastic section. He entered this activity with all his might and succeeded to improve the section considerably and was well–liked by all the association's members. Skavirsky's service to Rovno's Maccabee is worthy of praise. I will mention only one detail: the income from just one successful performance of his team enabled I. Lipin, the chairman of the association's committee, to purchase all the main equipment we needed. Skavirsky developed the team, expanded it and made it the pride and joy of Rovno's Zionists and all the city's Jews.

The active members among Maccabee were: the brothers Wolkowitz, I. Gorinstein, I. Lipin, Syuma Bookimer, Moshe Licht, Arye Gorinstein and German, in addition to the first group (Daitshman, Gilbord and Teitelbaum made Aliya), who were prominent among the players and activists of the association. Many recall the first Sportive Ball in Salianka; Maccabee demonstrated its achievements in gymnastics and was rewarded with applause and cheering. After that ball Maccabee felt it could venture out into the world.

|

|

Maccabee Soccer Team with coach Shponer from “Hacoach” Vienna – 1921 |

[Page 255]

|

|

The committee of Shomria Sport Association – 1931

Standing (from right): Yonah Wiener, Haya Drumneska (Laden), Yosef Feinstein, Moshe Gaser

Sitting (from right): Meir Gilerman, Dr. Moshe Chemerinsky, Avraham Rise, Yaakov Boshel |

In summer 1921 Maccabee's activities were stopped temporarily due to regime change, also because Skavirsky left Rovno. Some of Histadrut members made Aliya and there was not one active personality that could assemble the association's undertakings. But shortly after matters fell into place, new members joined the association and it rose again. Maccabee performed in competitive games with non–Jewish teams and scored many soccer wins. In one of these games, in 1922, a game was played between “Halerchik” Polish Club team and Maccabee's Team on Sokol Field. The game was long and Maccabee won 1 to 0 (in this game excelled Itzhak Gorinstein, Luba Rosencrantz, Moshe Licht, Vilye Perzinsky, Eliezer Lupatin, Lulik Rise and three other players). The public applause was incessant and evoked

|

|

(Under the photo) Shomria Committee – 1935

Standing (from right): Yonah Wiener, Pessach Fishgoyt, Aba Fishbein

Sitting (from right): Avigdor Burstein, Dr. Chmerinsky, Haya Ladan, Yaakov Boshel |

[Page 256]

jealousy. The Polish team was very upset and then began undermining Maccabee, until they found a ruse to annihilate it with the authorities' help. Not too long after this game, the authorities informed Maccabee that they did not have permission to operate in the border regions. With no other choice, the association ceased their activities, and its Rovno members were in mourning.

A delegation traveled to Warsaw and the case was presented to the Jewish representatives and to Maccabee's leadership. Meanwhile a new sportive group was organized in Rovno, at first by the name “Hagibor” (“The Hero”) composed of Maccabee members, and later under the name “Hasmonean”. With the help of Warsaw lobbying, this association was registered and recognized by the Polish Authorities. All Maccabee's members transferred to Hasmonean and with renewed forces, with ambition and consciousness they now dedicated themselves to sport and physical education, which made an impression even on the Polish world of sport. Hasmonean had Zionist entrepreneurs and sport–lovers who helped, and it acquired its own field and club.

Hasmonean

by Eliezer Lerner

Translation by Naomi Gal

There were many sport aficionados in Rovno since the foundation of Maccabee's Association in 1918 by the activists of Histadrut, the student–association. Indeed, the national sport conquered the Jewish Youth's hearts under the Ukrainian Regime and later the Polish Regime and drew many closer to the Eretz Yisroel Idea.

Hasmonean Association did even more in this respect (the new name for Maccabee that was closed by the Polish Authorities). In those days Zionism was flourishing in the city but the economic situation of Rovno's Jews was dire. The youth were intoxicated by the reports arriving from Israel and Aliya seemed attractive. Many desired to make Aliya and join the builders of the homeland, and Hasmonean members begun preparing for Aliya and to a new life in their forefathers' country.

Meanwhile, Hasmonean celebrated its official inauguration.

After many preparations, the ceremony was held on August 18, 1923 on Sokol sports field. It was a big Zionist festive gathering with the presence of the City's Zionists and out–of–town guests. An audience of thousands attended, listened to the opening speeches and watched the gymnastic exercises, which were professional and left a huge impact.

Maccabee's success was also Hasmonean's success. Moreover, when Hasmonean was founded not only Maccabee members transferred, but also members of general associations, who could only find their place in a Jewish sport association, with clear nationalist tendencies.

With the help of the Zionist entrepreneurs who were dedicated to Hasmonean from its first day, the association leased a special field in the city's outskirts, on the road to Bassovkut that was prepared for games

[Page 257]

and activities, and on April 25, 1924 the field opened for Rovno's Jewish youth. They did not settle for it but went on with their efforts till the Hasmonean was able to rent Prince Lubomirsky's big building, not too far from the old castle, and host there the association's club. Because of this move, Hasmonean was able to regularly conduct its sportive activities not only in summer, but in winter too. But after two years the building was taken away from the association; its Polish competitors were responsible, and the lack of cash that worsened caused this as well. A period of decline and depletion of members began for Hasmonean.

1927 was a fertile year in Rovno's national sports. At the head of the different sections were: I. Gorinstein, M. Meziover and I. Karlik. At that time, a group of girls was assembled for sports and Hasmonean was doing well but an unexpected surprise occurred: Talmud Torah's Hall that was allocated for sport was taken away from Hasmonean. All arguments and demands were useless – they had to look for another location. They searched and found a hall that was previously a dance–hall. The move from one place to the other damaged the activities somewhat.

Finally, some veteran entrepreneurs got on board, amid them: Haim Efrat, Zechariah Warny, Haim Gelman, Hertz–Meir Fissyook, Dr. Rotfeld, I. Galperin, Volya Grenfeld, Parnass, Gasha Freeman (secretary) and came to the association's rescue.

In May 1927, the association renewed its forces and went public again. The previous building was again rented for a few years and joy returned to Hasmonean. It again showed up in competitive games and was successful. It obtained second prize and then Volhynia's Championship in soccer and was leading in other sports, too. The association once again had good, nimble and qualified players who trained and were dedicated; some said Lady Luck intervened…

In 1932 a fateful event took place and affected the association, its existence and development. The big field was in need of repairs. The members volunteered for this job since the organization had no funds, and they labored day and night until the field became suitable; they put a fence around it and paved a special access road. A year later Hasmonean celebrated on this field, fifteen years since the Maccabee, first Jewish Sports Association, was founded; this became a big celebration for all Rovno's Jews and friends of the National Sport. Since then all the city's Jewish athletes were under Hasmonean flag. Because the field was close to Austia River they arranged a special beach for the river bathers and the youth used to go there, swim, bath and enjoy.

The gymnastic section was run in 1930 by coach Krinker from Vilna. He did this job with remarkable talent and Passover's 1930 games were a forceful Jewish demonstration in Rovno.

At that time began Hasmonean Aliya to Israel. The adolescent members were attracted to Aliya – the Zionist vision demanded it, Chalutz Organizations and the youth movements sent their members to training, the events in Eretz Yisroel required Aliya; could Hasmonean members stand aside? And they made Aliya, individually and in groups, and when they arrived in Israel they joined the ranks of the laborers and the builders. After the first: Doitchman, Teitelbaum, Gilbord, Gorenstein, Winokor, others made Aliya too: Hinkis, Libiatin, Eliezer Lerner and others.

[Page 258]

Due to quarrels and inner–disputes a group of a few dozen separated itself and created their own sport–club “Hakoach”, but after a while they came back.

The Hasmonean organized another sportive activity: ice skating.

During the winter Hasmonean activists prepared the place, and youth from all corners of town were drawn to the skating arena and spent there many hours. This turned ice–skating to a popular sport.

In 1932 Hasmonean basketball team won Volhynia's championship and participated in pre–games of all–Poland Championship. This was an important achievement, which encouraged Hasmoneans players to excel.

1935 was a year of preparations for Poland's Maccabee's championship games in Rovno, which took place in 1936 with the participation of the strong teams: Maccabee – Warsaw, Lodz, Krakow and Silesia; Hasmonean Lemberg, Rovno etc. Rovno's Hasmonean team excelled in those games and won Maccabee's championship in Poland. Beginning then, Rovno's Hasmonean provided talented players to other teams in competitive–games.

But that same lucky year caused Hasmonean disappointment as well: it lost the big rented hall it had for twelve years and the worry was great; it seemed this was the end of Jewish national sport in Rovno. But salvation came from another source: activists, headed by Litawer, Hasmonean honorary–secretary, who wanted to keep Hasmonean alive, no matter what. The leadership elected then – with Nahum Sterntel as chairman and engineer A. Litvak as his deputy, together with the other members: Pinhas Litaver, Meirovitz, Tokovitz, H. Leviter and others – joined forces and raised large sums of money to balance the past association's deficit and aimed, too, to buy a field and build a Hasmonean building appropriate for Rovno and its surroundings Jews' national sport. The field was purchased and in that same year a gorgeous building was built; the right conditions were now present to develop the activities of all sections of Rovno's Hasmonean, which was growing fast.

A year later, in 1937 Hasmonean won the regional championship and participated as the only Jewish team from Poland in the camp of the state's youth–champions. Hence, Rovno's sportive youth became famous all over Poland.

Hasmonean delegates participated with all the other Polish associations' delegations in “Maccabiah” that were held in Israel. Well remembered was their performance in the second Maccabiah in Eretz Yisroel and in games held in Lucerne during the nineteen Zionist Congress in 1935.

In 1938 Hasmonean Rovno celebrated with pomp and circumstance the twentieth year of Rovno's national sports club. The club was considered the oldest sportive club in Volhynia and attracted all the sport–associations in Volhynia and delegations from other cities. It was a national–Zionist holiday for Rovno's Jews and for all national sport movements. To celebrate the event a booklet was issued in Yiddish and Polish detailing Rovno's sport history and its achievements.

Close to the breaking of World War Two, when Poland's Maccabee Team traveled to Hitler's Germany to participate in soccer games, some Rovno's Hasmonean's athletes were added (Winoker and others).

[Page 259]

In memorial: these are the names of Rovno's Maccabee and Hasmonean activists who perished before they were able to make Aliya to their homeland: Hinkis, Itzhak Gorinstein, M. Gorinstein, Simcha Gimberg, Yosef Leviatin, Paltnik, brothers Savitzky, brothers Leviter, Soffer, Winokor, Shimshon, Licht, David Feldman, Friedmiter, Brikman, Israel Tov, Catchko, Braker, Zindel, Kozlik, Steindel.

Together with the above–mentioned activists who worked for Rovno's sport, the sport's trustees should be remembered, too: Roisman, Avraham Zam, Moshe Turkovitz, Motobilovker and others. Also remembered admiringly are the club representatives in Poland Dr. Henrik Rosemarin, and Dr. Fogel from Warsaw and the Poles Dziboliak and Banasia from Lutsk, who helped the club on every occasion and were its visitors and supporters.

A Jewish Drama Workshop

by Arye Harshak

Translation by Naomi Gal

The cultural evolvement of Rovno's Jewish youth in the twenties and the lack of a Jewish Theatre in Rovno motivated some theatre aficionados to found a troupe of amateur players, that in 1924 began rehearsing Yiddish plays. The troupe called itself A Jewish Dramatic Circle and attracted more than twenty members who took acting on stage seriously, knowledgeable of art and willing to serve the theatre.

The circle prepared under the guidance of Haim Moshar and Erlich and later Kurtz

|

|

The members of the Drama Circle |

[Page 260]

a gifted man who left for America, they all had previous experience on stage. The repertoire he prepared was of famous Jewish plays and he trained his friends according to their talents and capacities depending on the chosen play.

Titles of some of the circle's plays: Brother Luria, The Great Winning (Shalom Aleichem), Zippke Eshe, God, Man and Satan, Hinke–Pinke and others. After many rehearsals in friends' apartments (the circle did not have a place of its own) the circle performed in front of an audience and had moderate success. Charity institutions (like: “Linat Hasedek”, “Hachnasat Cala” “Hachnasat Orhim” etc.) began inviting the circle to perform during their balls. Their performances attracted large audiences and helped the institutions' income, while the circle performed for free. A few times the troupe performed out of town in the surrounding villages (Tustin, Kostopol) and pleased the crowds, most of the time on Saturday nights. The circle had no budget and it covered its expenses from ticket fees.

Beside Moshar and Erlich the members were Buzia Krantz, Avraham Krantz, Mochnik, Arye Harshak, Avraham Rise, Haya Yesod and a few others.

The circle existed for three to four years, until some of the members left town and some made Aliya.

The History of Rovno's Journalism

by B. S.

Translation by Naomi Gal

Before the Russian Revolution Rovno had general–public newspapers in Russian which closed during World War One due to Rovno's evacuation in 1915 and other war hazards. After the revolution, when the public breathed a sigh of relief and woke up to political–public activity, newsletters and different publications appeared written by different movements. The Bund and the Zionists tried their hand, as well, but with no success.

When the Germans arrived at Rovno with the consent of the Ukrainian Ataman Skoropadeskyi and ruled the city and its surroundings, a newspaper in Russian was born in 1918 called: “Prigorianski Cray”. The permit to publish the newspaper, granted by the German Authorities, was issued to a veteran of the Russian Army by the name of Wiess, and he was signed as the official editor but the actual editor was B. Smaliar, a Rovno native. Since the first issue, Smaliar's editorial–articles were published stressing his political and public opinions, which were not to the conquerors' liking.

Weiss, the official editor, went every day to the censor in the German Headquarters, to receive telegrams from “Wolf” agency. Once he was sick and Smaliar had to replace him. When Smaliar arrived at the censor he was cordially invited to one of the headquarters' workers' room. The German clerk said:

“You should know that Weiss is not sick, we asked him to pretend, so that you will come over. We discovered that you are the one who writes the articles and not him, and we regretfully have to say that we do not like them. We were already told they are harmful to us here and

[Page 261]

to all the border regions. Since we respect your talent and role we would like you to change direction and from now on publish articles that favor our occupation, since we seek the good of the place and its population, we will help with the newspaper's distribution, which you seem to need…”

The German waited for an answer, but Smaliar was unable to respond to the offer as he wished and he saw no point in arguing – so he chose to say he saw the conversation as terminated.

The German was angry and he changed his tone: “If things are that way we demand that your newspaper will be under our censorship from now on”, and indeed, the conversation was terminated. Smaliar rushed to Weiss, told him about the German Headquarters' command, but Weiss did not react. The next day the imaginary–sickness healed and Weiss took the newspaper to the censor, where they erased a few lines from the main–editorial and the published journal with its white, empty spaces evoked amazement and sensation. It continued that way for several days until the censor asked Weiss to submit the main–editorial hand–written, before printing. There was no choice but to send Smaliar's main–editorials to the censor before printing them. One day the article was delayed and was not sent back. Smaliar demanded Weiss to bring back the article, but the authorities' response was: the article is being submitted for investigation so that the writer will stand trial as an opposer to the Military Regime. However, if the writer would leave the newspaper – the article will be returned and the whole matter forgotten…

Smaliar was not inclined to mess with the foreign military authorities and chose to leave the editorial board. Weiss continued to publish the newspaper and for a while the Germans indeed distributed it on their account, but it was less popular.

Not too long afterward, Mr. Zalman Gasser, a printing–house owner who already had a license, decided to issue a newspaper. Gasser invited Smaliar to be the editor and Smaliar accepted. It was a nonpartisan newspaper named “Volhynskoye Slovo” was published in Russian. The population liked the new newspaper and its success was considerable. Smaliar continued with his line but edited cautiously. After a few weeks, an idea surfaced to publish a Public–Literary Magazine and Smaliar was again invited to be the editor. The name of the new publication was “Zeria” (Dawn), and this, too, was a success, especially among the youth.

With the upheaval of the times publishing a newspaper in Rovno was a prominent social endeavor, which had a great value for a city that was constantly growing and developing.

When the city was conquered by the Poles another newspaper was published in Rovno in 1920 in Russian called “Volhynia News” but it did not last long.

Rovno Mirrored in Local Newspapers

Translation by Naomi Gal

Some big and medium cities in Volhynia and in other places became famous as capitals and a region where Jews could succeed materialistically and spiritually. Also, from a Geographical–political aspect with time Volhynia's administration changed, and so, a few cities, Rovno among them, received the crown as the capital of culture in Volhynia.

[Page 262]

The Jews, historical pioneers of building and settling cities, were attracted to this new location and were welcomed by the lords of this place, who granted them privileges and concessions, as was done back then. Other elements worked as well for the new settlement that grew and developed exceptionally quickly and even was on par with cities with older histories. But the fate of this city was determined when the south–west and the Polesie (in the nineteen century) railroad was paved, crossed the city and turned her into an important crossroad with big commercial routes.

Rovno reached a peak in its development in the beginning of the twentieth century, especially after World War One, when it became a prominent Volhynia city. Although administratively–wise the authorities set Lutsk as Volhynia's center, being further away from the border, in all other aspects Rovno was the un–crowned capital of Volhynia, particularly from a Jewish point–of–view. All Volhynia's distinguished cities laid their crowns at Rovno's feet and accepted her mastery. But Rovno, not only guarded carefully these crowns, handled them with love and added colors and ornaments of her own, but also expanded her control with conquests of her own.

So, Rovno was now an economic–commercial, national–political and educational–cultural center for lively and exuberant Volhynia. In Rovno was founded the regional committee of the Tarbut movement, from which stemmed Torah and education, guidance and assistance to all the area schools; Rovno was the driving force in the different national and social movements and guided hundreds of branches in the provincial towns; a wide net of national, municipal and social public–institutions drew support and encouragement from their regional centers in Rovno; the idea of Volhynia's Journalism, which played a prominent educational role in training teams of local writers–journalists and instilling the civil–social consciousness to the masses – were all born in Rovno. There is no counting the number of essential areas of action that Rovno served as voice and advocate, teacher and guide in Volhynia's cities and its surrounding.

The goal we set for ourselves is, in this Yizkor book, to record in Rovno's memory, its branched activities, which were stopped by a cruel, very harsh hand. It is particularly difficult to do in the frame of a short article, because no matter how detailed our accounts are, they will not suffice in–view of the real greatness of things that happened. But this is no reason for not doing what we can do. So, let us reveal in full Rovno's life story as we saw it in her newspapers in the last period of her existence, when we had not yet envisioned the nightmare of her destruction.

True, there are faults not only advantages in this choice, since we limit ourselves to one period of time, but this period of life and death is worth more than many other long periods. All the thousands of people who lived and were active in those days and forged the image of thriving Rovno are the same people who saw her horrible dying moments, and when the huge mass grave was sealed over them so was sealed Rovno, the arena of their lives. Hence, it will be a real act of grace for them, as well as for Rovno, if we will enter, through reading old newspaper pages, into every home and establishment, every office and corner where they were working at their tables and workshops and remember them and their endeavors and their names and characteristics for our own eyes and the eyes of future generations.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Rivne, Ukraine

Rivne, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 May 2018 by JH