|

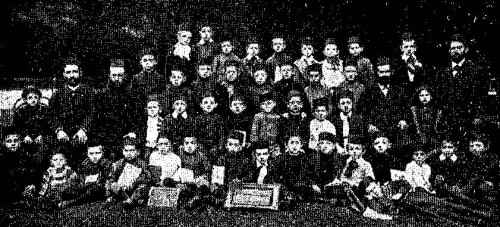

Teachers and students of a Corrected Cheder

|

|

[Page 185]

Blowing Winds

Translation by Naomi Gal

The Hassidic wind that blew in Volhynia maintained an important position in Rovno, which was in the distant past a Hassidic Center. There certainly were some objectors, but quarrels between the sides were unknown. Since the Magid Rabbi Dov–Ber lived in the city, it is doubtful if the objectors dared go against the Hassidim, and according to the generation's elders, the Hassidim once had full control in the city.

There is a known story dating 60–70 years ago (told by W. Z., a Rovno citizen), that when he once entered the “Cloise” in a short jacket, an old man reprimanded him saying: “All these years our city was full of God–fearing Hassidim, the holiness of the Magid floated over our community, the opposers were disabled, and here you, the “Berliners” Israel–opposers arrive to stab our backs?” The man tried to explain and justify, saying that no one in our city follows Berlin's educational philosophy, and that one should not suspect seekers who want to understand their real spirit and cultural force, but the old man refused to listen to the explanation and just added: “What explanation do I need if you first cut your jackets and then your “Mitzvot”…you are heretics, repent while there is still time and do not endanger Israel and its Torah”.

The old man's bitterness was understandable, since all his generation believed the way he did, in the “Cloise” (synagogue) and outside of it, and this was the attitude in those days. The masses of Jews in the city were believers–the–sons–of–believers, and every search for new ways in the Israeli Thought and the Renewal road seemed to them as hurting their very soul, their most sacred values, and was heresy to the God of Israel, distancing heretics from Israel's Religion and its sanctity. Ignorance and Hassidim reigned then among the city's Jews, and it is only natural that rumors about education frightened them. The whole world of these generations was keeping Israel's laws, fulfilling the Mitzvot, praying and continuing in the tradition of the fathers. Any other way of life was not only foreign to them, but seemed improper, condemned and loathsome. The sojourn of the writer Avrum–Bar Gotlober in Rovno during the eighties of the last century (1880's) was unacceptable to them and kept away from public awareness. Meeting Gotlober, visiting or listening to him, or reading his books, or the books of Riva”l, (Isaac Baer Levinsohn) or Smolenskin's “Hashahar” was a sin in their eyes, God Forbid.

But what the mind does not do – time does. Slowly–slowly, contradicting the old beliefs, were born advanced thoughts of reviving and renewing Israel's way of thinking, understanding the people's culture and its treasures, uprooting ignorance and shedding light on Jewish lives, their abodes and their public life. Indeed, the owners of these thoughts did not intend to copy Berlin's intellectual plans, but the religious Hassidim did not consider right or wrong and negated any and every advanced thought.

The new winds of time were first absorbed in the villages around Rovno (Tuszyn, Alexandria and more). Youth there began reading “HaShahar” (Alexandria's sons remember the initiators Lizak, Hening and the youngsters who were later teachers at the “Corrected Cheder”: Blay, Zaks and Kaplan) and being educated on the books that were published at that time in Hebrew. The influence

[Page 186]

of Isaac Baer Levinsohn from nearby Krementz and of Gotlober, who in his old age lived a few years in Rovno, was great. The teacher Goldarbyter (first in Alexandria and then in Rovno) was very close to Gotlober and visited him often. Wolf Zam, one of the city's educated youngsters, and some Yeshiva students who later became teachers in Rovno, came to visit him and listen to his theories. Since the thirst was great, people from around town came secretly to meet him, talk to him, browse his books and become intoxicated with his spirit.

Elimelech Blay tells that in 1885, when he once came to Rovno as his father's messenger for business (he was then 14 years old), he lingered in the city and went to Gotlober. When the host asked what was it he wanted, he did not know how to respond since his heart was full of wishes he was unable to express. He listened to Gotlober and received from him the book he wrote about Humboldt – and an invitation for another visit. The next time Gotlober suggested that he travel to Vilna to study with Steinberg or go to America; Gotlober was willing to give him recommendation letters that would introduce him there. Once he heard from him about the writers and poets of the generation, he encouraged him to learn Torah and literature and spread the knowledge amid young people. Blay used to come back captivated from every visit with Gotlober. Of course, his father and grandfather had no idea about these visits and it was inconceivable to reveal this secret.

As soon as the buds of the new ideas begun blooming in Rovno and it was publicly known, the religious leaders panicked: “Did the evil reach us, too?”; on the other hand, there were indifferent Jews who did not take it seriously – let the kids have fun…

But time did its thing. The number of people affected by outside's influence grew and there were hundreds who were moving closer to the views of the Renewal Movement. They read the relevant books, met and discussed them together, and finally decided to start by educating the toddlers by way of “Hebrew in Hebrew” (in this area the nearby villages proceeded Rovno – Tuszyn, Alexandria, Brastsheko and others).

Around 1883 “Hibat Zion” association was founded in Rovno and eight years later also “Safa Berura” (“A Clear Language”) by the young Nahum Shtif, Noah Greenberg, Shlomo Vesslir, Moshe Bokovitzki, Noah Gilbord and others. The goal of the second association was to spread Hebrew among youth and the people, and its first mission was to create a Hebrew Library. This cultural endeavor was joined by the teachers Goldarbyter, Dannenberg and young Yosef Edel, Shmuel Melamed, Sandler and others. From the library room on the Volya many imbibed National theories and Zionism, and from there the philosophy broke out and captivated the minds and hearts of the youth. Sons of Hassidim together with searchers thronged to learn about Zionism and literature – the gates were broken and it became clear that although Rovno had remained the same for generations, the idea of national renewal uprooted her from the old frame, revived and changed her.

And so, the city was captured by the winds of time. The Zionist preachers for Settling Eretz Yisroel (Drahizin, Yahushua Bochmil, Yosef Ze'ev, Zvi Hirsh Mesliensky and others) deepened and widened Hibat–Zion and the idea of renewal in Rovno's hearts and their words came at the right time. Alongside the old Cheders, modern Corrected Cheders were established and the Hebrew spirit celebrated its victory. Although the Hassidic status did not change and no one crushed it, it was no longer a force in the general development. The Jewish way of life was especially influenced during the period of political parties 1904–1906 during

[Page 187]

the years of World War One and the Russian revolution – the national consciousness of masses of Jews in Rovno matured, as it did in other cities, towns and villages. Under the new conditions a new Jewish experience evolved. The young people, who grew up during the war and were forged during the revolution and Ukraine's riots, felt their world narrowing and so they burst into the new space with full national consciousness. Wishing to distance themselves from Ukraine's killing–fields, the dream about making Aliya to Eretz Yisroel became real. The Zionist idea became a yearning, and the Zionist's awakening in Rovno and all the other Jewish settlements became the only individual and multitude's goal, at the same time a Hebrew movement developed and kindergartens, schools and a Hebrew Gymnasium sprouted in Rovno and instilled rays of light in every single Jewish home in town. Hebrew was heard not only in schools, but also in Yeshivas and the streets. The old Cheder diminished and many were knocking on the Hebrew institutions' doors – Tarbut became an organic part of Zionism and was a living fact amid Rovno's Jews.

by Arye Ben–Menahem

Translation by Naomi Gal

Until the end of last century Rovno's Jews knew that their sons' education was solely in Cheder by a melamed depending on the level: first “Young Children's Melamed” for beginners, then “Teaching Humash” and finally “Gemara Melamed”, as it was that way in every Jewish community. Very few sent their children to Government Schools, and this only after they learned in a Cheder. There were dozens of old–fashioned Cheders in Rovno, most of them on Krassna, Shekolna streets and on the Volya. During the holydays, the melameds used to roam the streets looking for pupils for their Cheders. Most of the melameds were from nearby towns and villages and their number increased during the holydays. Not all of them were fit to teach due to lack of experience or meager knowledge. Each new teacher would open a Cheder and invite an assistant if he had enough students. Every Cheder occupied a living–room in a private apartment, if not in the teacher's apartment, with no adequate arrangements and no accommodations. The melamed, called back then “Rabbi” used to sit at the head of a large table with “Kanchik” (a whip with leather stripes for punishment) in his hand and conduct dozens of children of different levels and ages, who sat around the table. Sometimes the “rabbi” sent for a while one level children outside, so that they would not disrupt other levels' studies, and some of them used to set every child free on his own after he completed his reading of the “Siddur” and the child would go and play in the corridor or in the street.

The Cheder served as an educational device for the Jewish child's soul from age two–three and the preparation of the child depended on the capacity and taste of the Melamed. Rovno's children went to Cheder mostly until their Bar–Mitzvah. Not all of them stayed with the same melamed. Some changed Cheders and melameds; often the children had to adapt to the routine of a new cheder and its special educational system and to every melamed who felt he had to change his interpretation, to distinguish him from other melameds.

[Page 188]

Indeed, the old cheder was faulty, but one has to admit that in this way the children of Israel learned Torah and tradition according to the times, until a new wind begun blowing in education and Jewish life in general. The enlightened era arrived and new ways of teaching emerged, similar to other people, and Rovno's Jews liked the idea of Corrected Cheder that at first was installed in few of Volhynia villages (Alexandria, Brastsheko and others). This was an important step to advance education and raising a Hebrew National generation in a modern way. Some educated teachers and melameds established Corrected Cheder in Rovno, too, and the old cheder approach was slowly slipping away. The veteran melamed did not give up easily his status and income; they enlisted the old generation, especially the die–hards among them, to defend the old cheder that “kept the light”. The battle was long and hard, yet all the melameds begun to instill new ways into their cheders and tried to come closer to the Corrected Cheder's style in order to attract pupils and sustain their livelihood. Hence, modernization entered traditional cheders as well, which went on operating alongside the Corrected Cheder. The demands of the Russian Government that the melameds be tested on their knowledge, despite being in a clear anti–Semitic spirit, helped advance their degree of expertise.

In 1908 Rovno still had some old–fashioned cheders, but the Jews preferred to send their children to private schools, that were really Corrected Cheders run by Lemel Kolker on the Volya with four teachers: Rivenson, Peralyook, Borstein and Isenberg (who was there since 1905). Amid the old–fashioned cheders are remembered: R' Meir from Krassna Street, R' Wolf Frishberg on the Volya, R' Baruch Blay from Mele Minska Street, R' Pinhas Korizer from Shkolna Street, R' Itzhak Hochberg from Manijeni alley, Zechariah Zechziger from Niemeska Street, Ben–Zion Shlifstein on the Volya, R' Alter the Gemara Melamed from Krassna Street, R' Yoel Kabzan (that was known as Yoelnik the melamed), in the Shoemakers' Street, he too taught Gemara, Matil Krivoroshka, a beginner's melamed in the Shoemakers Street, Alter Bord, young children's teacher, Pinhas Klide that had a Modern Cheder in a school form, Baruch Drajner, Shmuel Spektor, Yosef Apel, R' Dov Bilinsky, called Berly Zusses (who became a melamed for older boys after he lost everything in the big fire and taught the sons of the respected citizens in town: Yehezkel Oirbach, Shlomo Koliko–Bitcher, Haim Porzia, Ben Bronstein and some others). Some of these cheders became closer to Corrected Cheders and in order to attract students became actual corrected cheders. Among those melameds will be remembered Haim Yojlevsky, Pinhas Hirschfeld, Avraham Shekliar, Yona–Leib Rosenfeld (one of Rovno's first Zionists), Smaliar, Sucharczuk, and Avraham Goycrch (who from the beginning founded his Cheder as a Hebrew School on Tomrovska Street that existed also during the Polish Regime). Most of the city's children were part of these Cheders, and we should credit them and their successors not only with Hebrew, – learning in Hebrew, and teaching their hundreds of students to speak in Hebrew, but also for training their hearts for Zionism and the Nation's assets. These students were educated in the spirit of the nation and were natural Zionists from an early age imbibing the Jewish spirit and the basics of its culture, many of them were drawn to Israel and later made Aliya, and to this day they remember respectfully their first teachers–educators in Rovno, their city, that directed their spirit toward the revival of the people and its culture and planted in their hearts a deep love for the language and the motherland.

[Page 189]

|

|

Teachers and students of a Corrected Cheder |

Students are talking about some of the melameds and the teachers:

R' Yosel Tismnizer a Jewish scholar full of wisdom, an enthusiastic Hassid of Rijin dynasty who taught boys Gemara and used to go to their homes to teach them Torah. He knew how to instill knowledge in his students and established a generation of Mishna and Talmud learners.

R' Pessah Goycrach. A Jew with an imposing–figure and soft–spoken. They called him r' Passy the Melamed from Manijny Alley. He used to teach small children and for many years taught Torah in his own cheder. Most of his students went on to study in Corrected Cheder of his son, Avraham Goycrach. He was a Jew who cared about public needs, one of the builders of Mishnayot Synagogue and its manager for many years. A wise man who symbolized the landlord of his generation. Died in 1911 at the age of 70.

R' Itzhak Hochberg. Rovno's one of the oldest melameds from the nineties of last century, a great scholar and a humble man, who had hundreds of students. At first, he tried to be a merchant but he was unsuccessful and turned to teaching, opening a Cheder in his house on Manijni Alley. They called him R' Itche the melamed. It was not easy for R' Itche to get a teaching license from the czar's authorities, which was given to those who passed a test following an investigation about administration capability.

For a time, R' Itche had two assistants for the young classes in his Cheder and was very popular on the Volya, but as he grew older, he lost his prestige; young melameds surfaced and the old melamed was tossed aside. In the last years of his life he settled for one assistant (Yaakov Guz) since the number of his students sunk to twenty only. During these years he suffered from aches but suffered them in silence. He was one of the founders of Mishnayot Society and one of the builders of the synagogue by this name on the Volya. He had three sons and two daughters (Wolf, one of his sons, was one of the leaders of Rovno's Bund in 1905–1907, was arrested in 1907, exiled from Russia and died in a foreign land). Haya–Sara, his wife, was known as a woman of valor. In the winter of 1907 R' Itzhak Haim died, he was 73 years old.

R' Itzhak Birstein. Many of Rovno sons know him as R' Itzhak the melamed and the cantor. They used to call him R' Itche the cantor, although he spent most of his life teaching on the Volya. Since he was one of the founders of the prayer–house for Ulik Hassidim, he also served

[Page 190]

there as a manager all his life without a fee. R' Itche was able to fulfill his mission as a melamed and cantor at the same time. The sons of Rovno remember his pleasant voice, which captivated hearts. Since he prayed from his heart he did not seek traditional ways of cantors, but sang directly to God. And since his livelihood all the years came from teaching he settled for very little (there were no rich teachers in Rovno…) and concentrated all his thoughts to his prayer–house, for its thriving and promotion. Most of his students were sons of those who prayed at the Ulik prayer–house, all admired and respected him.

R' Itche was not only a teacher and prayer–leader but he was a moderator and conciliated different issues and was almost always able to find a peaceful compromise. As a Hassid amid Hassidim R' Itche was close to the Hassidic Leader from Ulik and used to visit him often, and when the Rabbi visited Rovno he was his assistant. When R' Itche was old he accepted the invitation of a modern cantor for Yom Kippur's prayers, which was a great sacrifice…

The last news from him arrived in Israel in 1938 and his fate is unknown.

R' Yosef Apel. He came from Dubno to Rovno in 1908 and went on teaching; he taught youngsters and adults. An educated Jew and a learner, a bright man with good manners. The best of youth were accepted to his Cheder on Krassna Street. He was famous, and well–respected in the city. Indeed, his students thrived, and some parents whose children studied in general schools sent them to R' Apel in the afternoons to complement their knowledge of Torah and Gemara. R' Yosef was a Zionist sympathizer and stayed good–mannered all his life.

R' Shlomo Richman (born in Dubno) arrived in Rovno during World War One, taught in R' Asher Lemel Kolker school and later at Etz–Haim Yeshiva, but mainly was a private teacher and taught Hebrew and sacred studies in the students' houses. He was a wise man and fought for Hebrew.

R' Yonatan Hamelamed. One of the best teachers of the last generation. He was a melamed even before World War One and never abandoned his teachings. They said about him: R' Yonatan and teaching are like body and soul. He managed to make learning vivid, explained and elaborated in–depth, kept the framework while aiming toward modern systems. Lately, when most of Rovno children did not need Cheders any longer because they were in general or Hebrew schools – R' Yonatan did a lot to save the honor of Torah from oblivion. The religious in the city knew this and highly appreciated R' Yonatan. He also taught the week's Parashah to landlords in the big synagogue. R' Moshe–Eliezer Rotenberg was one of his greatest supporters, he knew him well and kept him close. When the association Mishna Learners was founded in the great synagogue, E' Yonatan was assigned to be the teacher and the interpreter, because his clear explanations and his deep knowledge made him stand out.

In 1912 Mr. Sholkovsky visited Rovno as the inspector of the Society of Education Distributers. He was visiting Volhynia settlements to explore the situation of Jewish education in general and in Cheders especially. According to his report he visited five settlements in Volhynia (Zhitomir, Rovno, Kovel, Torchin and Alexandria) in 108 such cheders. And this is what he wrote about Rovno*:

[Page 191]

“The teachers of Rovno are more evolved than the melameds in the four other places I visited in Volhynia. The Cheders with most students are Rovno's Cheders. The age of the students in Rovno's cheders (the same is true for Zhitomir) is from 5 to 14–years–old. The students study in the Cheder 6–7 years. The children's' language is, like in all other places, the spoken language (Yiddish), although they regard teaching in that language with ridicule and contempt. All the teaching is confined to mechanical copying of the example the melamed prepares for his students. In Rovno, too, the influence of the melamed's wife (the Rebezen) on her husband–educational work is felt.

The budget of the “Cheder” in Rovno is bigger than in other places. The melameds income is on average 446 Rubles a year (the smallest income is in Torchin – 185 rubles). As for the Cheders' future, the melameds themselves are in despair, they all complain and are worried. According to them the rich avoid sending their children to the Cheder, which they look down upon. The students – the Cheder visitors – are undisciplined and have no enthusiasm for learning. Those with means invite Hebrew and Torah teachers to their homes, these are “Home Melameds”. In the five above mentioned settlements there are 110 registered such “Home Melameds”, and the number of children studying in Cheders in those locations is up to 3219. The Cheders appears as the only open education institute for Jewish children in Volhynia so densely populated with Jews, since the general elementary school is almost closed for Jewish children and the number of schools for Jews is very low.

Among the different Cheders – 11.1% are traditional cheders, and the teachers are Torah–learners from Lithuania. Gradually, a new type is immerging, of improved cheders, not like the “Corrected Cheder” (which are becoming like schools). These types of cheders do not have yet a steady form, they are still mid–way between the old cheder and the corrected cheder and they represent 5.5% of all cheders. The old melamed view the new ones with anger and resentment, but they all exist and each continues in his own way…”

The melameds had their own status. They hardly made a living and many of them needed other incomes (being a cantor, a matchmaker, mediating etc.)

* According to “Zeman” 2/24/1912

by Eliyahu Rizman

Translation by Naomi Gal

One of the first Zionist actions in the beginning of the century in Rovno was to found a Hebrew Public Library, in which the city's intellectuals invested many resources to insure its development. (It is almost certain that this library was the continuation of the library of Safa Berura Association). There were only Hebrew books in this library – from medieval literature to the new literature of the time. The library had about 30 members who all worked for it. They paid a monthly fee to the library's treasury and from this income, new books were purchased. They also attracted new members and readers and regarded the library as a spiritual–cultural institution for withdrawing wisdom and human and Jewish culture. Indeed, many of the intelligent youth in the city were nourished by the library. At first the library was in the house of Herschel Baruch on Krassna Street, and from there, it moved to several locations.

Once a year an assembly of the library members was held, the passing year was summed up and a new director and six librarians on duty were elected, each one had his day. And so, from year to year,

[Page 192]

the library grew slowly, until there was a rupture and peace was disturbed.

One of the first founding members of the library was Nahum Shtif, who changed his taste and was attracted to Yiddish; this caused the controversy and around this a language–fight erupted between the members.

This was around 1904, when Shtif came back to Rovno from Kiev, where he was studying, as he was now a Yiddish supporter and partisan. A few youngsters gathered around him. Those were the days of searching for direction and the “Cultural Autonomy” of the Bund. Shtif easily found an attentive audience and supporters also among the city's library supporters. And then came the yearly assembly of the library members and Shtif suggested they turn the library to a Hebrew–Yiddish institution, meaning to add books in Yiddish and open it to the masses. The suggestion was met with the objection of most of the library members who saw themselves loyal to Hebrew and did not want to add Yiddish books to the library. Some were against this on principal, and others feared that the Yiddish books would dominate the Hebrew books and that the readers would become accustomed to reading in Yiddish, which was against their Zionist consciousness. Lively arguments ensued and war broke between the sides. Shtif, who was creative and adamant, came up with all kinds of reasons and explanations to defend his stand. His supporters assisted him, but they were unable to convince their opponents and the suggestion was rejected.

The Hebrew supporters were victorious and their Hebrew zeal increased. They felt they were protecting the national assets. But Shtif and his friends were angry, and without getting the right to speak after the suggestion was turned down, gave a decisive speech in response, and in a moment of fury held a copper candlestick with a burning candle that stood on the table, and fuming, threw it to the side of the assembly's chairman. Luckily for both, the candlestick fell on the bookcase and hurt no one, only the bookcase glass was shuttered to tiny pieces and the sound of the explosion was accompanied by the laughter of the Hebrew supporters…

by Arye Avatichi

Translation by Naomi Gal

The national awakening that was felt in Rovno and the conquest of Zionism brought forth a Hebrew movement. Learning Hebrew in Hebrew began in the Corrected Cheders that were established and sustained by private Hebrew teachers and Rovno's educated Jews sent their sons to be educated there. When – (around 1910) permission was granted for the Hovevei Sefat–Ever (“Lovers of Hebrew”) Association, a Rovno branch was opened in 1911. Until then the Odessa Council of Hovevei–Zion were the only ones who were allowed and hence openly operated in Zionist areas recognized by the authority. But since the opening of the Hovevei Sefat–Ever Branch, Rovno's Zionists were able to act under the branch's flag and conduct cultural activities and other Zionist endeavors that could follow the branch's regulations.

Most of Rovno's Zionists were registered as members in Hovevei Sefat–Ever local branch and became regulars of the Hebrew Club, and a Hebrew atmosphere was felt in the city. To the first committee of the branch were elected: Dr. Yehezkel Oirbouch (the head of the city's Zionists back then) who

[Page 193]

was the chairman, Zalman Greenfeld (later a rabbi in town) – secretary, and members of the committee: Nahum Shtrik, Yehuda Motyook, Hykel Kopelman, Lieb Isenberg, Berl Corech, Shlomo Wessler, the teacher Konivsky and others.

Club. In the beginning the branch opened a club in the house of the teacher Ze'ev Goldarbyter, in Keniejesky Alley that served as a center for members and Zionists. Every evening and on Sabbath men and women members met there, especially adults who spoke Hebrew and savored in this corner the Hebrew spirit and culture. In the club there were Hebrew newspapers, booklets and different books. Some of the club frequenters used to hold discussions and once a week (most of the time on Sabbath) they offered lectures that attracted many. Amid the lecturers and moderators were: the students Ze'ev Finkelstein (Now Soham, in Haifa), Shlomo Brez, Lieb Icenberg, Zalman Greenfeld, Moshe Berger, the teachers Hykel Kopelman, Rivnson, and Rabbi Zalman Goldenberg, Laybish Harif from Slavuta, the poet Yaakov Lerner from Kostopol, the teacher Lissize, Azriel Goringut from Krementz, the teacher Halaf from Caliban and others.

Night classes. Another important endeavor of Hovevei Sefat–Ever' s branch in Rovno was opening Hebrew night classes for adults. These lessons taught Hebrew to many of the older adolescents and gave them Hebrew consciousness.

Mendele Ball. That year, 1911, the cultural Jewish world celebrated the seventy–fifth anniversary of Sholem Yankev Abramovich AKA “Garndfater Medele”. (“Mendele Mocher Sforim – the Book Seller”). Meetings and big celebrations were held in many cities and villages in Russia, admiration and love for the great writer were expressed, appreciating his creations and the style he brought to our literature. During the meetings his works were read and the anniversary was celebrated with splendor and opulence.

Hovevei Sefat–Ever association in Rovno celebrated this event, too; first it sent congratulations to the celebrant himself, and after getting permission from the authority made the necessary preparations – organized a public literary ball, which Rovno sons remember as “Mendele's Ball”. The ball took place in the big hall of the “Justice League” on Zamkoveya Street with the participation of the writer R' Mordechai'le (Chemrinsky), who was invited from Warsaw, the local governmental Rabbi Zalman Goldenberg, the famous cantor Yaakov Frooman (who was back then in Rovno) and his daughter, the singer, the boy–violinist Itzhak Edel, the young painter Binyamin Hassin, the teachers and the Zionist activists of the city. The hall was beautifully decorated – pictures, flowers and flags, and a big picture of Mendele, which was especially painted for this ball by the above mentioned Hassin. An atmosphere of festivities reigned in the hall even during the preparations for this big ball.

The Jewish public from Rovno and its surrounding came in a large group to the ball. Long before the ball began all the tickets were sold. VIP's who arrived late, or people from neighboring towns who arrived at the last moment, had to stay outside, for there was no space in the hall. Hundreds of people were pushing at the entrance and the policemen who were keeping order had a difficult time restraining them. They remained standing outside and listened through open windows and doors.

The Yiddish people were excited, and they had good reasons. According to them Mendele was theirs, but then came the Zionists who claimed him under their own flag. They had no choice but to attend the ball as the guests of Hovevei Sefat–Ever and as lovers of Mendele they did.

Zalman Greenfeld opened the ball in Hebrew; he was then the secretary of Hovevei Sefat–Ever. Afterward Rabbi Goldenberg spoke, he greeted the anniversary–celebrant in the name of Rovno's public and Hovevei Sefat–Ever,

[Page 194]

who admittedly was the great popular writer of this generation; he went on to talk about his writings and its value to the people and future generations. During the break after his talk Edel played Kol Nidrei on his violin and a popular Jewish song that touched the audience.

The writer R' Mordechai'le extolled Mendele's greatness and analyzed some of his stories, claiming him to be one of the best Jewish writers. He remarked on Mendele's special attitude to literature and emphasized that Mendele's creativity stemmed from his spiritual connection to the people. According to him Mendele nourished the people with spiritual food that was absorbed by all Jews, since he had a sharp eye and deep understanding, and was sent through this great gift to be a messenger in this renewal generation, fighting for the simple man, who make up the majority of people in the diaspora.

R' Mordechai'le speech was in Yiddish and lasted more than an hour and was enthusiastically received by the public. Afterwards the chorus of Zeirei–Zion sang some national songs in Hebrew and Yiddish. The last to speak was Wolf Finkelstein, the student, who was much liked in Rovno. His words, in fluent Hebrew, were heard with concentration. Finally, cantor Fruman, accompanied by the chorus and Sara, his daughter, sung “God, God why did you forsake me”. The ball, which ended with the singing of Hatikvah by the chorus and the audience, left an unforgettable impression on all participants.

When the club grew and the number of interested people increased, they had to move the club to a more spacious apartment in a central place in the city, and so they rented a big hall with adjacent rooms in Geshel House on Shossejna Street. The new club was nicely decorated and the branch kept evolving. Many youth and students flowed to the club, which soon became a center. Young women, who were remote from the national movement and knew no Hebrew – became close to Zionism thanks to their visits to the club, where interesting literary parties and national balls took place.

One day, Simha Klarich, from Brezezno, passed through Rovno, he was back then a young man – a student in Moscow. When he came to visit his brother, a Rovno inhabitant, the Zionists delayed him and he gave a lecture in the new club. Many people came to hear the student from Moscow lecture in Hebrew, in which he was able to sincerely express the different movements in the generation's culture and in the national movement, and he gave good answers to the public's questions. That was in Passover 1911 and since then they began concentrating on attracting literary forces to public speeches. The opportunity soon arrived. Around this time Itamar Ben–Yehuda (AKA Ben–Avi, the son of Eliezer Ben–Yehuda from Jerusalem) and his wife were visiting Russia with his wife. The leaders of Hovevei Sefat–Ever used this visit and invited him to speak in some central cities. After he spoke in Odessa and Kiev he was invited to Rovno. Rovno's Jews came in masses to hear a land–of–Israel lecturer, many of them flocked from surrounding towns and villages. Ben–Avi's lecture was a massive manifestation of the renewing Hebrew language and the Zionist Idea. Rovno's Zionist held a magnificent party for the couple from Eretz Yisroel and spent with them hours talking, singing and dancing. The lecture, as well as the party gave the Zionists a breath of fresh air, especially the young ones, who were intoxicated by the lively Hebrew talk. The impression was great. The visitors stayed in Rovno three days, those were days of celebration and propaganda for the revival of the language and the motherland.

In the spring of 1912 “Ha–tsfira” Hebrew paper celebrated its 50th anniversary. The day of celebration in Warsaw was set for April 18. Many preparations preceded this celebration in Warsaw and in other cities.

[Page 195]

|

|

The committee and the activists of Hovevei Sefat–ever association with Ben–Avi and his wife |

Hovevei Sefat–Ever in Rovno sent a delegate to the celebration – Rabbi Zalman Goldenberg. The non–Zionists, most of them inclined to Yiddish, saw the need to send a congratulation–letter for this anniversary. Since the letter was signed by the senders, some Zionists interfered and added their signatures to create a mayhem… and this was the letter:

“Fifty years ago, at the dawn of our education, you made your first appearance, dear “Tsfira”, on your lips a cry for light and knowledge edged on your front. As a ray bearing solace and hope you accessed all our hidden corners and woke up the generation's pioneers to plant. A generation comes and goes but you paved your way confidently, you were alert to every heartbeat and soul tremor of our nation, you knew its pain and voiced its lament, and fought continually and relentlessly the war of its justice…The damage of time did not restrain you, with faith and bravery you stood up to all the obstacles and hindrances, and after fifty years of the people's work, you are now standing in front of us better and improved and in your hand the flag of hope and revival. And on this day, when you are fifty years old, we are sending you, dear Tsfira, congratulations from all the appreciators of our literature, we give our blessing, too: May your light never fade! The road is still long, the war still waging!”

Rovno April 11, 1912

The lovers of Israeli Literature in Rovno – signatures

Among those who signed the letter were VIPs like Nahum Shtif, Moshe Zilberfarb (who later served as a minister in the Ukrainian Government), Ze'ev Finkelstein (who served as a Zionist executive in London and is now a lawyer in Haifa) and others.

At that time the Yiddish lovers – the remains of the leftist parties – were active under the patronage of the Merchants Association that was recognized by the authorities. Their activity was limited, but when they celebrated the jubilee of Hillel Zeitlin, they asked

[Page 196]

for a lecture by the jubilee celebrant and asked Sefat–Ever's Council for a permit. It was granted and the Yiddish group began preparing. In those days Hillel Zeitlin published a critical article against Ussishkin, which upset Rovno's Zionists. They complained to Hovevei Sefat–Ever's Council, who informed the lecture organizers that they had reneged on their lecture permit. The organizers were bitter and embarrassed over this insult. So, they summoned Hovevei Sefat–Ever for an honorable mediation. Both sides invited Mr. Shershevsky, a well–liked senior in Rovno's Ezovy Bank. Itzhak Melamed was the advocate on behalf of Sefat–Ever and Moshe Zilberfarb on the Yiddish side. Friends from both sides came to hear charges and complaints by both adversaries. The advocate for each side argued angrily, pushed, pressed and harangued each other and it seemed endless, until Yosef Shpitelnik (from the Zionists) called Nahum Shtif (then one of the Yiddish contenders) and told him that all arguments are in vain since a message was already sent to Zeitlin by Hovevei Sefat–Ever's Council that his lecture had been canceled. The information passed to the advocate and the others who, angry and furious, left the mediation. The Zionists were happy they settled the matter. Since then the Yiddish camp bore a grudge against Rovno's Zionists. Zeitlin heard about it and he published in the “Hynet” a sharp article full of cursing profusely Rovno's Hovevei Sefat–Ever. That was the end of the story.

In fall 1912 arrived at Rovno from Kiev the activist and lecturer Y. Margolin, sent by Hillel Zlatopolsky, for language and cultural matters. His mission was to connect the center with the provincial towns' Zionist Associations in Kiev's region. In the meeting held with him it was suggested he lecture to youth who are sympathetic to Zionism. At the appointed hour a few dozen young women and men arrived at Yosef Shpitelnik, and Margolin came, too. Primak, Shpitelnik's landlord, got scared, fearing the authorities and he hurried to Shpitelnik's store to demand about the reunion and ask to please cancel it. Shpitelnik calmed Primak saying that he had a permit from the Head of the Police and pretended to go and fetch it, to prove it was indeed true. Actually, Shpitelnik sat for more than an hour in Itzhak Melamed's house, until the reunion was over and the participants all went peacefully home. According to Rovno's activists, Margolin's words had awakened the youth to Zionist and Hebrew activities.

That same year the association of Hovevei Sefat–ever held a public lecture by the author–speaker Haim Greenberg. Greenberg's appearance and his lecture deepened the Hebrew consciousness and strengthened Rovno's Zionist camp.

After a few months (the winter of that year) Ze'ev Jabotinsky gave at the Zafran Theatre his famous lecture “The Language of the Hebrew Culture”, that was organized by Hovevei Sefat–Ever. His lecture made a huge impression and quieted the voices of the accusers and Zion–objectors, and increased the prestige of Hovevei Sefat–Ever, which was active till World War One broke in July 1914.

by Zehava Bat–Itzhak (Birstein)

Translation by Naomi Gal

Many changes occurred in Rovno pertaining to teaching Hebrew to adults in night–classes. Even before World War One Hovevei Sefat–Ever organized Hebrew night–classes, and a few dozen adolescents, especially Zionism sympathizers, acquired knowledge in the Hebrew language and culture. They also attended the association's club and participated in conversations and lectures and adapted the Hebrew way of talking.

Culture and Zionism were one for us, the national youth seeking an ideological and spiritual fulcrum. I remember the visits of Haim Greenberg and Jabotinsky, who lectured in Hebrew in the big hall of the “Justice League”, and we, who back then did not speak the language and understood only a few sentences and words, felt compelled to learn and know it. We told ourselves that it's impossible to be Zionists without knowing the people's national–language. So, we registered for night–classes and dedicated ourselves to learning Hebrew. I rejoiced in any sign of advancement and saw it as a victory. In the night–classes I found young men and women who worked during the day and devoted the evening to studying Hebrew, read Hebrew books and like me, attended Zionist meetings.

Among the teachers who taught Hebrew with zeal and stood out were Borstein, Rivenson, Eisenberg and Zalman Greenfeld, but the other teachers were also dedicated and interested in teaching the language and Zionism. The banner of Hovevei Sefat–Ever Association was back then enough of a camouflage from the authority for our studies and meetings. Fearing the policemen, we used to go to night–classes on our own and after classes we dispersed cautiously as to not awaken their wariness. And when once they were suspicious about the location of our studies, and policemen came to interrogate us about the purpose of our meeting at the association on Topoluva Street, we swiftly ran away through the windows to the nearby park and from there to the city's streets, and we were successful…

And then, after the Russian Revolution, when all the movements, including Zionist, begun enthusiastic activities, and started also cultural and propaganda activities, the idea of learning Hebrew came naturally, and the Hebrew teachers, who were all in the Zionist camp, volunteered to teach the language. Night–classes for youth and adults were again founded, attracted many and served as a motivating and advancing force for Zionism.

According to the plan studies were scheduled three times a week, but some classes decided to convene on Saturday for an extra class. We learned Hebrew in Hebrew and did very well. We dared speak Hebrew not only in class but also in the street; and although we did not know much – the Hebrew on our lips sounded like a living language. For those fluent a special circle was created, led by the senior teachers Kopelman, Goldarbyter and Eisenberg. The Zionists were the ones who were in charge of the night–classes, especially Zeirai–Zion. Together with the teachers they monitored the frequenters of the Zionism classes. Not too long after everybody was serving the movement and many of them were the first pioneers who made Aliya.

As the educational–cultural endeavor grew, two rooms were rented with the meager income from the students' fees (there was no other income for the night–classes). This is where

[Page 198]

we convened and studied. Knowing the bible and the history of Israel brought the participants of the classes closer to Eretz–Israel, and Zalman Greenfeld had a big part in it, because he was able to captivate our young hearts for the Hebrew language and its sources (he was not officially Zionist). A short while later, when Greenfeld was elected as Rabbi, he left the night–classes, and when Tarbut, the Hebrew Gymnasium was founded, the night–classes were moved to the gymnasium and continued to exist. In the evenings the gymnasium was busy with the night classes' students, who were in the hundreds. They learned their Zionism. too, and many became active Zionists. With time Shmuel Rozenhak, the young teacher, joined the evening teachers; he was a pioneer and Hebrew aficionado, whose enthusiasm for Zionist pioneering rubbed off on us.

Indeed, the number of the Hebrew learners in the night–classes in Tarbut Gymnasium reached hundreds, but there were those who were organized in small groups for continued education programs, on top of the night–classes. The Zionism–objectors used to joke: “Hebrew is in–fashion with the Zionists”, but we were not hurt by the sting; our perseverance and consciousness did not leave us, and our knowledge strengthened in us the hope to fulfill our pioneering goal – to make Aliya and be among the revivers of our motherland. The teacher Roznak taught us the language with the Sephardic accent that is common in Israel, and we saw ourselves on the verge of the yearned–for land. He used to conduct sing–along in the intermissions between classes and after classes, and that way we learned Israel's songs. To this day I remember that summer evening while we stayed sitting in class and learned the song “My Homeland”. It was at sunset, and while being immersed in the song we forgot that the lesson is over. I did, as did all my friends, repeat the song dozens of times till we memorized it. Only two years later, when I had the privilege of making Aliya and living here, in Israel – I understood the real meaning of this song.

The knowledge we gained in Rovno's night–classes eased our acclimatization in the different corners of our homeland.

by Eliyahu Richman

Translation by Naomi Gal

Rovno did not know pure–Yiddish education till the end of World War Two. All the Jewish children studied in Cheder or in state schools for Jews on Optikarssa–Gogolevska Street, in Municipal Schools and a few in the Reali School, in the girls' gymnasium and at the merchant school, where there was no mention of Yiddish. Only when Rovno absorbed a flow of refugees who were supported by the local Jewish population and the special committee for refugees did the problem of education and Yiddish arise.

With “Kapa” and later Joint public money a children's home was founded, managed by kindergarten–teachers in Yiddish, and put under Yiddish influence in the city. The school for Jewish boys, where Yiddish teachers taught, was named after I.L. Peretz and the language was changed from Russian to Yiddish. On Afrikanska Street on the Volia, an elementary school was opened named Shalom–Aleichem;

[Page 199]

|

|

The Elementary School Named after Shalom–Aleichem |

Where Yiddish was taught, also, there was an initiative to teach Yiddish in night–classes for adults from working classes.

When the Polish Regime was established in the city in 1920 the existing education institutions were recognized. It was necessary to register every institution and get a permit to continue its functioning, since the net of Yiddish Schools existed in Poland under the name “Tzyshe” Warsaw issued an order to establish a branch in Rovno, where the educational institutions would be gathered. On the registration's request form were signatures of the teacher Mirar, A. Richman and others, parents of the students who looked “Kosher” to the authorities; the regulations were certified and with it – Rovno's Yiddish Schools. In the building of Talmud–Torah a third elementary school for boys and girls was organized and the number of the students was about thirty. Most of the children found places in the schools and in Tarbut Gymnasium, and only the children of Yiddish zealots or from poor households visited the Yiddish institutions, which became weaker from year to year.

In 1921 the I.L. Peretz School ceased to exist and after a year the Shalom–Aleichem School was closed, too. The General–Polish Schools and Tarbut absorbed the students of these schools.

by Yehezkel Flachs

Translation by Naomi Gal

Besides Cheder, Talmud–Torah and private Hebrew Schools, there were at the beginning of the century in Rovno a number of general–governmental schools, public and private, where Jewish children were educated, like: The Governmental–Elementary School, the Municipal School, The National School for Jewish boys, the Reali High school, the Governmental Gymnasium for girls and the Rosenthal's private pro–gymnasium. At that time a school was opened

[Page 200]

“Torgovaye Schola” that later became a school of commerce (high–school) with eight classes. Some of Rovno's young men and women were studying at the same time in high–schools in nearby villages: Dubno, Lutsk, Zhytomyr and others. With the population's growth, a great need was felt for more high–schools and so a boys' Gymnasium was founded. Supposedly it was a general school, but most students were Jewish.

After the Russian Revolution, the national school for Jews became a Yiddish school named after I.L. Peretz and at the same time a similar school was created on the Volia named after Sholom Aleichem. The teachers in both schools, who were Yiddish teachers, made sure the schools were mainly Yiddish and they were part of the institutions that were built with the Joint, Yekopo and other public bodies. (Launched in Russia in 1914, Yekopo established local branches throughout Eastern Europe to aid Jewish victims of pogroms and World War I.)

In 1919 Tarbut, the Hebrew Gymnasium was founded in Rovno together with a Hebrew shelter for refugee and poor children. In time three elementary schools were set up in the city established by Tarbut. The Yiddish lovers added educational institutions, but not as many.

Under the Ukrainian Regime a private Ukrainian–Jewish Gymnasium was founded in Rovno, that went through different stages, until it became a Polish Gymnasium. After five years, when the Polish Regime was well established in town, Mr. Flashner founded the Polish Gymnasium “Oshvieta”. Although a general school, only Jews studied there.

There were eight classes in Oshvieta Gymnasium and about 300 students. It was lodged in a new building, close to the Polish Governmental Gymnasium, which replaced the previous boys' gymnasium. In this gymnasium Hebrew was taught and the level was high. No wonder then, that as a privileged school it attracted students from Tarbut Gymnasium that was still lacking privileges. There was a national atmosphere in this gymnasium and there were permanent ties with Tarbut's students. The students joined national youth movements and many of its graduates made Aliya through these youth movements. In surveys conducted among these gymnasium students, most students expressed their yearning for Eretz–Israel, where they saw their future…

The Commerce School was established in 1910 and it was then the second high school in town. The initiators were Jews, parents who were unable to get their children to the National Reali School and wanted to give them commercial education. Indeed, how could a commercial city like Rovno do without an educational institution with a commercial emphasis? And so, a general school was set up, and it was mostly Jewish.

The director and the driving force was Mr. Zvitayev, a liberal man from the advanced Russian Intelligentsia, who was called after the Russian revolution to be a temporary mayor. He was always well–liked by the parents and the students. The school had eight classes, and they were all full with Jewish students, except a few Christians who were there by chance. The years of World War One delayed the schools' development, but it still existed. The changes that took place as a result of the Russian Revolution

[Page 201]

impacted education in general and high–schools particularly, similar to this school. In the big public parade in the Revolution's honor in March 1917 the school's students marched with their flag among other schools and an excess of freedom pervaded the school, which was not always a blessing and interrupted the level of education and the school's order. The teachers did not know how to control their students and discipline was non–existent. The students' committee that represented all spoke in the time's language without consideration and one day Shtil, (who later became a communist) appeared as the commissariat's representative and took charge. The agitation ran deep and was prominent…

Remembered is a case that happened in the school with an Ukrainian teacher, who was teaching at the school before the revolution. This teacher wrote an anti–Semite article; some said that he was very blunt and deeply insulted the Jews. The students convened, discussed, delivered speeches against the teacher and demanded that the director punish the anti–Semite teacher. At the same time, they passed a decision not to pass exams in arithmetic and Ukrainian. The director received the students' delegation and calmed them down and asked them to be patient till the matter was cleared and settled. Indeed, after the exams Zvitayev found a way to get rid of this teacher and the students celebrated their victory.

Generally, there was a national atmosphere in the school, most of the students were part of the Zionist Students' Union and were regular visitors in its club on Topolyova Street, that was named after Dr. Yehiel Chelnov. There were some arguments against national views and thoughts, but the non–Zionists did not weaken the enthusiasm of those who were part of the movement and joined it devotedly.

A private gymnasium in 1918, when Rovno was under the joint regime of the German occupation army and Skoropadsky, Ukrainian Hetman's Government and it seemed as if the world was returning to normal after the Great War and the political revolution in Russia, a need was felt in the city for an Ukrainian high school that would be in the spirit of the times with suitable levels available for students without schools. This is when Voroviyov founded the Ukrainian Gymnasium with the authorities' required curriculum. The gymnasium was lodged in Hirsh Heller's house on the Volia and was immediately filled with students, most of them Jews from the city and its surroundings. The gymnasium had good opportunities to evolve, especially since Rovno's Jews saw it as an Ukrainian establishment, although they did not know yet to what degree it would satisfy the existing Ukrainian authorities. They said: time will pass until changes and corrections would be made in the city's high schools, while a new institution that was founded by the authorities' instructions and in its spirit is likely to stay and enjoy the given privileges. Hence, they blessed the opening of the gymnasium by Voroviyov and perceived it as the right thing at the right time.

But soon enough it became clear that Voroviyov could not maintain and sustain the gymnasium by himself, and before the second year the students' parents committee had to take on the responsibility, although Voroviyov remained the one who held the license and was a salaried director of the gymnasium. That year the number of students increased, and since the building was unsuitable, the lack of elementary basics impacted its development.

When time came for the (WWI–1918) Germans exit from Rovno, the ascent of Petliura, the entrance and exit of the Bolsheviks and more, which hurt daily life, brought forth the decline of the young gymnasium, and when things became worse, it was about to be closed. Luckily a savior was found – Dr. Guzman. This happened in 1921, when the Polish regime had settled down. The gymnasium, like the other schools, needed permission for renewal by the Polish authorities and adaptation of its program to the new curriculum. Dr. Guzman arrived, handled the matter with all his energy and turned the gymnasium into a Jewish–Polish institution. Most of the students stayed and there were even new ones, and Dr. Guzman found the means and was able to get the necessary permit for its opening. Then the gymnasium thrived and grew, and with the help of a few local activists, Avraham Guzik heading them, it became a respected school. Hebrew was largely taught in this gymnasium (there was the need and demand), and many of the gymnasium graduates were active Zionists in Rovno and made Aliya.

The Mathematical–Physical Gymnasium. This gymnasium was established as a continuation of the Commercial School in Rovno following World War One. The teachers were from Galicia and Congressional Poland. It was lucky since the relationship between teachers and students were good, something that did not come easily in other schools. This not only helped the good atmosphere in the school, but had a positive influence on the studies and the modifications that took place with the general Polish shift in the school. The governmental institutions wished to eradicate the Russian past in education and in life and to instill the Polish spirit and culture in the schools, aiming to turn the border–towns to Polish fortresses. But this aim did not bear fruit. Most of the students were organized in Zionist and pioneer youth movements and Polish way of life was foreign to them.

The head of the gymnasium was Berliner, one of the greatest mathematicians in the country. He was an excellent pedagogue, a proud Jew, a descendent of the Maharal, (Judah Loew ben Bezalel) and he saw his role not only as providing the required knowledge according to the curriculum, but also in preparing and training the students for their life and future as humans and as Jews. Remembered is his public appearance in Zafram Theatre celebrating the inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and his comprehensive speech on the generation's obligation and the roles the youth have to play, summoning them to continue the prophets and the nation greatest endeavors. He empathized the development of science in the world and in Israel and as part of Jewish education and stressed how important is the great endeavor of founding the university in Eretz–Israel. His words had a huge impact.

Different circles were organized next to the gymnasium to clarify scientific questions and philosophical problems with the guidance of the gymnasium's teachers and director, who gave their time and energies to this end. One of them was the senior Hebrew teacher Haim–Haikel Bergman, an educated and outstanding pedagogue, who saw his life purpose as drawing the youth to the Hebrew language and Israel's culture.

[Page 203]

In his many lectures he tried and succeeded to describe and depict to us the nobility and divine in Jewish Wisdom, especially the bible, and enriched our knowledge of new literature and the literary works he edited; he acted as their driving force.

The class of aesthetics and drama was directed by the teacher Georgy Petrovitz Kossmiadi, non–Jew, a regular in Jewish homes since childhood. The students loved him and his influence was great, he had a special attitude toward his students. He knew how to develop their aesthetic sense, and his merits made him liked by all. When he directed a play, he used to devote himself with enthusiasm and dedication and instill his feelings in the hearts of the students who participated in the play, until the result on stage was natural and perfect; (many recall the play “The Post Office” by Rabindranath Tagore at the Zafran Theatre that was enthusiastically acclaimed by the school's students and the public).

Mentioning these courses, one has to remember the Nature Lovers' class that made out–of–town fieldtrips, collecting plants, butterflies and other insects in order to understand nature and its studies. There were also extra–courses of mathematics, history, literature and more. These classes attracted the students and deepened their knowledge.

One of the endeavors of the students in this school was the one of helping each other, which included all the students. One of the main aims was to assist any needy friend with material, advice and guidance. Students from modest homes were helped with purchasing books, notebooks, as well as excursions' expenses etc., most of all – with paying the gymnasium's tuition. There were cases in which students were helped secretly, unbeknown to them.

The gymnasium thrived from year to year, and the national spirit that reigned there brought it close to Tarbut, the Hebrew gymnasium. Most of the students were members of the Zionist Youth Organization in the city, and those who were captivated by pioneering made Aliya after their graduation and found their place in the motherland. The gymnasium's graduates in Israel were part of the “Haganah” and also brought over their families, and many of them have responsible jobs. They all remember with love their gymnasium, its teachers and the guides of its extra–courses.

The State Reali School and the State Gymnasium for Girls. Replacing the Municipal School, the Russian Government maintained for many years, the Polish Education Ministry founded a general elementary school with Polish as teaching language. This school had children from all religions in town. The curriculum was the general syllabus of elementary–schools in Poland, with some deviations for mixed populations in border–towns; a place was allocated also to religious studies for each denomination and Hebrew was included in the curriculum

[Page 204]

Hence, the Jewish children acquired in this school general education and some knowledge of Hebrew. This is why there were many Jewish students in this school and many had to remain outside for lack of space. In his report about 1924 the journalist Asher Shtil, remarked that the Jewish representatives in the magistrate did not add more classes in this general school, so that all who wanted, could get in. According to him the school had an adequate level of studies.

The Railroad School The children of the workers and servers of the train received their education in this special school and there were a few Jewish children in this school. The curriculum was the regular one for elementary–schools under the supervision of the education's general inspector.

The Music School. Among the many educational institutions in Rovno was the Music School (Conservatorium) founded in 1927–1928. For many years the school was in Shkolna Street, next to the Catholic Church, under the direction of Zelny. It was a Polish Institute but most of its students were Jewish. In its first years there were only 30 to 40 students, but during the thirties, the number of students reached 70 and more, and it went on growing.

In this school playing and singing was taught and there were outstanding talents (according to the late Aaron Rosenboym, who excelled in this school), who could have had a great future in music, but most of them perished.

During the Soviet Regime, before the German Occupation (1939–1941) the school was still open and moved to Lenin Street (before Directoraska) and one of the teachers was Clara Shtif, born in Rovno.

|

|

The General Elementary–School (the teachers and an upper class) – 1924 |

[Page 205]

The School named after Shalom–Aleichem was founded in 1917 as an elementary–school. Boys and girls seven years and older studied there. There were six classes and it was under the supervision of Education Distributers Company. They taught Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, geography, history, natural–science, mathematics. The teaching language was Yiddish but there was a large place for Hebrew, until it was overtaken by the Yiddish supporters, and the direction and curriculum changed. The Yiddish pushed the Hebrew away until it was expelled from this school.

The school's principal was Lea Haron. Amid the teachers were Mrs. Burstein, Israel Zins and another woman–teacher. There were about two–hundred students in the school, most of them from middle or lower–classes in town, especially from refugees' families absorbed by Rovno.

When the Poles occupied the city, the Governmental School was closed to Jews and the teachers, who belonged to Bund, transferred to the Shalom–Aleichem school.

When, in 1920, Tarbut activities evolved in Rovno, some children transferred from this school to Tarbut Gymnasium. This migration increased, especially after the Yiddish Spirit, which was unwelcomed by Zionist or traditional parents, dominated this school.

Still, it has to be said that from this school many educated children emerged and found their place in professional school like ORT or in Hebrew or general school, in Chalutz ranks and other youth movements that saw their future in Eretz–Israel.

by Shmuel Rosnak

Translation by Naomi Gal

A Zionist atmosphere surrounded the majority of the Jews in Volhynia, which was annexed to Poland at the end of World War One. Polish was not yet the spoken language, but although as time went on it became more and more part of everyday life – the Polish Authorities had a hard time uprooting the Zionist and Hebrew roots that went deep into the Jewish soil in Volhynia and Polesie. The schools' net, that the Zionist begun founding under the Russian and Ukrainian Regimes and went on prospering and evolving under the Polish Regime, stood like a wall, despite the different winds blowing from al sides. The Hebrew School found its way into the hearts of the Jewish students and their parents and served as a basis for original Hebrew Culture, satisfying the Zionist yearning, after the Russian Schools were closed and the old Cheder ceased. Education Institutions teaching in Hebrew sprouted all over.

Tarbut Company, founded under the Russian Regime, continued to exist in Ukraine and later in Poland and played a prominent role in the area of Hebrew–National culture and education. The kindergartens, elementary–schools and the gymnasiums, and the Hebrew night–classes,

[Page 206]

diverse circles and courses – they all became the Zionist voice of Volhynia. From them were born the fulfilling Chalutz and they educated the young generation toward pure Zionism and Aliya – to build and renew. Those who were close to Hebrew education during the twenties and the thirties in Poland would testify that the Hebrew Schools created an educational–Zionist ideology that did not take into consideration accepted pedagogical regulations while giving–up the mother–tongue (Yiddish) and striving to teach the Hebrew language, spirit and culture to the growing–generation, to train it for pioneering and fulfillment.

There were Hebrew Schools in some of Volhynia towns and villages before the Polish Occupation, and they had some educated and visionary teachers. A considerable number of the teachers, who before taught in Corrected Cheders or in private Hebrew Schools, transferred to Tarbut Schools in an effort to adapt to Tarbut's educational spirit. There were some teachers who studied in teachers–seminaries founded by Kahanshtam and Tcherno in Kiev and Krakow and lately Vilna, too. There were also teachers who were educated in Western–Europe, most of them from Galicia. With time, the ways and systems merged and these schools integrated their desired character in Tarbut's framework. Hence, the Hebrew elementary and high–schools found their pedagogical and organizational frame. Tarbut's regional council that was subordinated in Rovno to the Central Zionist Chamber and later on as part of Warsaw's Tarbut Center, was very active sustaining and developing Volhynia's schools in every aspect.

Zionist Rovno was in a Hebrew–Zionist tension all that time. The Hebrew prestige grew especially when Tarbut Gymnasium was created in the school year of 1919–1920 (after it had already Hebrew kindergartens and elementary–schools), which became the head of the educational–cultural endeavor of Volhynia's Judaism and grew into a Zionist and cultural center for the whole region. This gymnasium had a power of attraction and an example for all the surroundings. The teachers from the outside received a spiritual and pedagogical inspiration from it and the parents' faith strengthened to believe that indeed, there are those who provide a holistic Jewish Education.

In the pedagogical conferences that took place in Rovno every now and then, most of the region's Hebrew teachers participated, striving toward loyalty to the spirit, the tendency and the wholeness of the educational ideology, as well as integrating meaningful content in the didactical and ways of learning in general. The realistic and Eretz–Israel orientation in Ludmir's school, which became an agriculture school – was the peak of this wish and the basis of cultivating this kind of educational institutions, if it were not for the tragic end of the whole Jewish population. Even a Tarbut publishing–house was created in Rovno with plans for the future, since the need was felt, and a storage for Tarbut Hebrew books was established in Rovno to satisfy the demands of the teachers and the students.

The blossoming of Zionism and culture in Rovno moved some leaders, writers and poets to visit her, get to know her closely, and thus, the city enjoyed the visits of VIPs, the greatest of these generations: H. N. Bialik, Shaul Tchernichovsky, Berl Katznelson and many messengers and different entrepreneurs, who all appreciated Rovno's rich cultural–educational endeavor before the Holocaust. Perhaps, when they saw the huge cultural undertaking that took place there, and understood its importance, they guided in some degree its direction and goal. There was mutual–influence in these visits and Rovno was intoxicated by them.

[Page 207]

Besides the Hebrew education and cultural institutions, there were social establishments that had educational programs and were valuable for several reasons. “Centos” “ORT” and “Taz” took care of the health and education of the masses' children, particularly the orphans – to heal and prepare them for life, and hence, complemented the work of the educational institutions. For example, the summer–camp endeavor and the boarding schools all year long and other activities of training and educating the children who were supervised by these institutions. Rovno's Zionists and Tarbut activists worked in these institutions and found there another venue to help the Jewish child and improve education in general. By the way, most of the children in these institutions received their education in Hebrew Schools and learned Zionism.

But there were shadows among the many lights. With time, the influence of the Polish Culture on education became more prominent and the use of the regime's language became more widespread in Rovno, too, and it introduced doubts in the young generation's soul. In certain circles they began speaking Polish (instead of Russian), although the children of these families knew Hebrew and were frequenting national youth movements. The street influence was felt, especially with youth who studied in general schools, where the teaching language was Polish. But this did not change the young generation's opinion and did not uproot its yearning for Eretz Yisroel. And in Rovno's soil, which proved to be very fertile for Zionism and Hebrew, all the youth national movements grew roots that attracted most youngsters, and only a small part was carried away with the bustling stream or stood aside.

It has to be said that the economic and political situation, on top of the yearning of the generation and the hope for a nation and redemption, pushed Rovno's Jews, similar to other places in Poland back then, to Zionist thought; and it's only natural that the idea appealed to the young generation who received a National–Hebrew education. And the road from yearning to pioneering fulfillment was not long. The rails led the toddler to Hebrew kindergarten and from there to elementary school and to the Hebrew Gymnasium, and beside studies – to a youth movement and sport association. The last stage for those seeking higher education was the Hebrew University in Jerusalem or the Technion in Haifa. Indeed, most of Rovno's youth that made Aliya turned to labor and building the land in different areas. Quite a number of young people completed their education in higher education schools in Europe and arrived in Israel afterwards, since their path was Zion and this is where they made their lives.

As for the language – the moderate attitude of certain circles among Polish Jews about the teaching–language and the demand of some leftists' movements to prefer Yiddish rather than Hebrew, were helpless against the growing force of the Hebrew education. The attitude of the Polish Government toward the existence of National Schools in the border–regions became less flexible, they were quite demanding and gave no monetary support, aiming to weaken the influence of schools where Russian was still the teaching–language. The Poles hoped to instill slowly the Polish language and culture into the Jews' lives and to withdraw them from agreements made with other minorities in the border–regions, and one of the ways was through education. However, Rovno's net of Hebrew Culture, as in all Volhynia, proved its strength and huge influence in educating for Zionism.

by Shmuel Rosnak

Translation by Naomi Gal

The rich cultural activity, including the Hebrew education institutes that were founded in Rovno and in all of Volhynia, which was under Polish Regime since 1920, demanded a framework that would include all the institutions, supervise and guide them. While Rovno's Zionist Center Chamber still existed, this role was filled to a large extent by the cultural office annexed to the chamber, but once the chamber missions were transferred to the Zionist center in Warsaw, and meanwhile a growing number of institutions in the region (there was hardly any village or town without a Hebrew School) had problems that needed solutions – it was decided with Tarbut Center in Warsaw to organize in Rovno a Chamber for Volhynia Region, with a regional committee and delegate to them the supervision of the institutions, and be responsible for the communications with Poland's Center.

It was obvious that no other town but Rovno would do as the seat of the regional committee, since Rovno was historically the center of the Volhynian's border–region, where

|

|

The members of the Committee and Tarbut Activists – 1919 |

there were already many cultural institutions and where the cultural forces were concentrated. The representatives of the cities Lutsk, Dubno, Austrvaah, Kovel and others understood this well and when they convened at the end of 1920, they elected the first committee that included: Haikel Witz and Yahushua Berger from Lutsk, Itzhak Gitlis and Yaakov Borek from Kovel, Pessah–Lieb Hirschfeld and Yosef Shpitalnik from Rovno, representatives from Dubno, Austrvaah, Ludmir, Korets, Sarny, Zdolbuniv and others. A special place was given to Tarbut activists like Shmuel Rosnak, Lavish Harif and others. Lavish Harif was invited to serve as secretary and director. Menahem Rivolov succeeded him for a while. The committee and its members and some Rovno's activists

[Page 209]

managed to do a lot for Volhynia Regions' education and cultural institutions.

One of the important action of the Regional Committee was to find and hire teachers, who were in great demand, for schools and kindergartens. The committee took part in Poland's Tarbut conferences and protected the rights of the Hebrew institutions that were under its influence and supervision. It was vital in negotiating with the authorities about the existence of these establishments. The committee was very helpful when it organized a conference of the high–schools' teachers and its activists in Warsaw, December 1922; it was dedicated to founding elementary schools where they were needed and managed in different ways their development and existence.

A local Tarbut Committee was founded in most of the towns and villages, and these local committees relied on the Regional Committee, accepting its instructions and guidance, since the committee served them loyally while supervising them. There was no doubt about the benefit of the regional committee which had a large impact on the cultural life of the Jews in Polish Volhynia. It became a supreme institute for culture and Zionist spirit in the region, and Rovno, its main city, was the place from where the Jewish voice emerged and was heard in the near and far surroundings.

The fast growing Tarbut activities in Rovno were manifested in institutions and establishments it continued to found. One of them was the endeavor “The Hebrew Morning for Children” in Purim 1920 for all Tarbut institutions in Rovno, which assembled hundreds of children and their parents and the city's Zionist community. To memorialize this morning, which was very successful “Mishloach Manot” was distributed to the children and special thank–you letters were given to the teachers of the institutions, which stated:

“To the principals of the cultural institutions, the teachers of middle and elementary schools, kindergarten teachers and the Hebrew Shelters in Rovno.

A warm greeting, and blessings for the revival of our fatherland that will soon arrive and on the knees of our ancient and living culture we will thrive. These blessings are sent to you from Rovno's Cultural Office adjacent to the Zionist Union. You succeeded, dear friends, in your important step, when you promoted the revival of our language and culture for everyone to recognize. The time's obstacles did not deter you and will not deter you in the future from your huge and important work, the work of educating a generation strong in its body and soul for our glorious future.

Blessed you are to the people, the builders of the people! Be strong and courageous!

| The office: M. Kadosh | Tarbut's Seal, Rovno's Branch: Y. Berman |

In the short time of Menahem Rivolov's sojourn in Rovno and his tenure in the Zionist Central Office in the regional committee, an important plan was executed for publishing Hebrew books, mainly for the schools, where the need was great, a partnership with Ahiassaf Publishing House in Warsaw was formed and some books were published, but due to the period's conditions and lack of manpower, the endeavor was liquidated in its second year.

Fondly remembered is the activity of the Regional Committee, which grew at the time I had the privilege to witness it, until I was summoned to serve in Tarbut Center in Warsaw.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Rivne, Ukraine

Rivne, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 May 2018 by JH