|

Source: Yad Vashem photo archives

|

Second World War Period

From September 1, 1939 until June 22, 1941

In the period between the outbreak of the war on September 1, 1939, until the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Vilna went through many changes of government and systems. Until September 19, 1939, there was great uncertainty as to the political fate awaiting Vilna in view of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, the complete collapse of the Polish state and the efforts made by the Lithuanian government in Kaunas to have Vilna returned to its rule. From September 19, 1939, until October 28, 1939, Vilna was under direct Soviet control. From September 28, 1939, until June 15, 1940, it was included in Lithuanian territory. From June 15, 1940, until June 22, 1941, it was part of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic.

First Days of Uncertainty

From the very first days of the war Vilna Jewry was uncertain of its fate. Simultaneously with the advance of the Wehrmacht masses of Jewish refugees fled to the city, bringing with them the first awful accounts of the cruel character of the Nazi conquest. On September 17, 1939, the Red Army crossed the eastern Polish border and annexed western Ukraine and western White Russia to the Soviet Union, in accordance with the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. A secret protocol to the Pact, which dealt with the interests of the Soviet Union and Germany in Lithuania, stated ‘both sides respect the interests of Lithuania in the Vilna area’, although in the amended Treaty it was laid down that Lithuania fell within the Soviet area of influence.

Period of Direct Soviet Rule

The Red Army entered Vilna on September 19, 1939. The Jews received it with mixed feelings,on the one hand they were saved from the German invasion, but on the other hand they were afraid of the anticipated political, economic and social changes brought by the Soviet regime. They had no illusions as to the attitude of the Soviets in matters of religion, Jewish national activity or the well-to-do class. In the very first days after the annexation arrests took place of political oppositionist activists, opening with the Revisionists and closing with the Bund. The number of detained was small, but enough to cause concern as to the fate of a number of sectors in the population. In contrast with the above was the fact that many Jews were accepted into the manifold branches of the administration and governmental and municipal services. Jewish communists, particularly young ones, participated in public activities including in the ranks of the militia. This short period in Jewish life in Vilna ended as early as on October 28, 1939, with the transfer of the city and its environs to Lithuanian rule.

The Period of Lithuanian Rule, October 28, 1939, until June 15, 1940

The transfer of power to Lithuania began with anti Jewish riots. On October 28, 1939, with the transfer of power, gangs of Polish and Lithuanian anti Semites began their rioting. A young Jew was murdered by the rioters and a few others injured. On October 31 the rioting increased and some 200 Jews were wounded. In view of the shortage of food the price of bread rose drastically and Polish and Lithuanian political elements used this to agitate against the Jews, accusing them of black marketeering, profiteering, and the hiding of food supplies. Gangs of Polish rioters broke into Jewish shops and plundered the contents. The riots spread throughout the city and Lithuanian policemen also participated. Young Jews who attempted to defend themselves were arrested by the Lithuanian police. Jewish community leaders, led by Dr Ya'akov Wigodski requested the Lithuanian authorities to stop the terror and when that was ineffective they turned to the commander of the Soviet garrison in nearby Wilejka, within the Soviet area. The Soviet commander sent tanks into the city and the riots came to an end, but the apprehension of their recurrence did not evaporate. On October 6, 1939, the Jewish community leadership demanded that the Lithuanian government guarantee the safety of the Jewish population in the city. Such a guarantee was given but the Vilna Jews, having learned from past experience not to depend on official Lithuanian protection, set up a self defense organization. All the Jewish political organs and the representatives of the refugees joined this body. Although the Lithuanian authorities agreed to arm the Jewish defense groups they conditioned this upon the agreement to act only within the Lithuanian forces. The Jews would not accept this condition and insisted on the principle of being independent in their own defense, thus remaining independently neutral. This way they hoped not to raise Polish ire against them, who, like the Lithuanians, had hoped to preserve their rule in the city.

In the days of the direct Soviet rule, before the city was transferred to Lithuanian hands, crowds of Jewish refugees flowed unhindered into the city, from the Polish areas under German occupation. Among the refugees were both unorganized individuals and family units, but mostly they came in orderly groups members of youth movements and members of khalutz training centers as well as a few yeshivas with rabbis and students. They left as soon as it became known that it was the intention of the Soviets to hand over Vilna and its environs to the Lithuanian government (the yeshivas were afraid more of the Soviets than of the Nazi terror). Members of the Zionist movements fled to Eastern Poland before the advancing German army. Later, they continued to flee to Lithuania and especially to Vilna. On the road, Jews joined the western Ukrainians and western White Russians who fled from the Soviets. Among these, members of Zionist youth movements and Yeshive students who insisted on continuing their life style stood out. By the end of 1939 some 10,000 Jewish refugees crowded into Vilna. A special refugees committee was set up chaired by Dr Ya'akov Rabinsohn. The representative of the ‘Joint’ in the city, Moses Bakelman also exerted himself greatly in assisting the refugees. The Rabbinic Rescue Committee, established in the USA and Canada, sent Dr Shmuel Schmidt to the city with the task of organizing economic assistance for the rabbis and to deal with their emigration.

At the beginning of 1940, the Soviets and the Lithuanians took special steps to deal with the illegal border crossings, but the infiltration of refugees across the border continued nevertheless. By the middle of June 1940, a short while before Lithuania became a Soviet republic, there were some 14,000 Jewish refugees in the whole of Lithuania, mostly in Vilna The refugees represented every political trend about 2,000 members of the khalutz movements belonged to the Khalutz Coordination (a body established to coordinate between the Zionist youth movements), about 1,000 Revisionists and members of Betar, about 3,000 members of Poalei Zion, about 550 members of the Bund, and over 2,500 yeshiva students, yeshiva rabbis and community rabbis. Most of the refugees saw in Vilna and Lithuania a temporary relocation station on their way to the ‘Free World’. A few Jewish national leaders in Poland found temporary shelter in Vilna, such as Moshe Kleinbaum (Sneh), Zerach Warhaftig and Menachem Begin. Jewish immigration offices, HIAS, HIZM, and the Eretz Yisrael Office, did their best to help the refugees to migrate to Eretz Yisrael, or to America or to any other country available. The Lithuanian government saw in these refugees a burden and did not hinder their efforts to leave, but the target countries placed strict quotas on the number of visas issued to Jews. Much formal and informal meetings and efforts had to be made in this respect. In the period when Vilna belonged to independent Lithuania, from autumn 1939 until the middle of 1940, about 1,000 refugees, mostly from Vilna, left Lithuania in various ways. The refugee problem remained a public issue also when Lithuania became a Soviet republic.

In the eight months of Lithuanian independence Vilna stood out like an island in a stormy sea of events that engulfed the Jewish communities those annexed to the Soviets and worse yet those under the German heel. Vilna remained the only Jewish center in Eastern Europe that retained contact with other Jewish centers throughout the world and drew to it Jews from the annexed Soviet area and also from the German occupied land. In the easy political climate created by the Lithuanian regime all the Jewish public bodies active before September 1939 were preserved in the city. The community council elected in 1939 provided all the services to the Jewish community within its power and the connections with other Jewish communities in Lithuania were strengthened. The separation from Warsaw, under Nazi occupation, furthered this tendency. Members of the Zionist youth movements and Zionist leaders who found themselves in Vilna because of the war continued on to the Lithuanian communities and strengthened the Zionist base. The Vilna Zionist Organization now became part of the Lithuanian Zionist Organization.

The increase in the number of yeshivas added to the religious life in the city. The yeshivas kept up almost full study activities, assisted by the JOINT and the ‘Rabbinic Rescue Committee’. The religious services continued on the same scale as before the war, the welfare services were expanded to assist the mass of refugees. Activities in the field of education and culture were intensive: thousands of children studied in the Jewish schools, YIVO continued its scientific work and literary circles and clubs continued their varied and lively activities. Three daily newspapers were published in the city containing many literary essays and publications. A historical society was established which collected evidence and details of harm and injury to Jews in the German conquered Poland.

Jewish economic activity-on the other hand-weakened in comparison to that of the period proceeding September 1939. The new border closed important Polish markets from Vilna merchants and struck hard at international connections. There were beginnings of economic connection with Lithuania, but within the short time little was achieved.

In the spring of 1940, the Lithuanian government ordered a reduction of the Polish presence in the capital, and many of the yeshiva students living there were transferred to towns in the vicinity. The Mir yeshiva, students and rabbis, moved to Kedainiai, the Kletsk yeshiva moved to Utena, and the Radon yeshiva was divided between Utena and Eisiskes.

The Lithuanian-Soviet Republic, June 15, 1940 until June 22, 1941

Vilna Jewry had had a taste of direct Soviet rule in the early days of the war, from the 19th until the 28th September, 1939. In those days they quickly learned of some of the characteristics of the regime: they witnessed the arrest of political opponents including Jewish public figures, the persecution of organizations having a national bent, and the oppression of people of means. The first period was too short to leave a lasting influence on Jewish life, but in the Lithuanian Soviet period radical changes took place in every aspect of Jewish life in Vilna and the surrounding area. At the end of June 1940, the communal institutions, public organizations and Jewish political parties were dissolved. Only members of the Communist Party and the Comsomol continued their activities, as part of the new regime and encouraged by the authorities. The Soviets began with arrests and some of the political opponents were exiled to Siberia. Before the elections to the new state institutions, which were intended to ratify the annexation of Lithuania to the Soviet Union, the Soviets conducted a vigorous propaganda campaign. The Jews and other national minorities were promised freedom from nationalist oppression who ‘exploited the masses for their own political and class benefits’. After the abolition of the previous political institutions the process of nationalization of banks, industrial plants, wholesale business and real estate began. During the nine months of Soviet rule 265 out of 370 Jewish-owned businesses in Vilna were nationalized. The process of nationalization of large industrial plants and wholesale business was fast compared to the pace of nationalization of the retail trade, but eventually the shopkeepers and the peddlers were forced to end their affairs, in particular because of the heavy tax burden imposed upon them. The Soviets also nationalized apartments, mainly large ones rented out, and their owners lost both the property and the income. Artisans were encouraged to form co-operatives (Artel). Indeed, most of them preferred this form of organization as against working for wages in large enterprises and thereby losing their independence. Considering the character of the regime, some of the members of the free professions, especially lawyers, had to change their occupation. The system of independent legal practice did not exist in the Soviet Union, and most of the Jewish lawyers sought work in other fields. The employment of Jewish teachers and doctors was basically altered: they now became employees of the state or the city but were able to continue in their work without much hindrance. Many Jews were integrated into the marketing and consumer chains belonging to the state or the cities. Jewish wage earners mostly continued to work in their usual work place, though there were occasional cases of workers leaving in order to better their positions professionally or materially. Most of the Jews previously unemployed now found work. The authorities emphasized that point in the propaganda and noted the fact that the regime offers security to the workers. To conclude, the changes that took place in the traditional Jewish economy were basic.

Jewish education underwent an accelerated process. Educational institutions which until June 1940 were under the aegis of the community and public bodies, such as the Zionists, the religious and the Bund passed into the hands of the state. In September 1940, with the opening of the new school year, the Jewish educational institutes were opened according to the Soviet system with Yiddish as the language of instruction. Subjects such as Tanakh, (Bible), Hebrew and Jewish national history were taken out of the syllabus. A few Jewish schools, mainly those having a religious bent, were closed and new ones opened instead. During the Soviet period Vilna had some 50 state educational institutes using Yiddish as the language of instruction: 4 kindergartens, 18 primary schools, 10 high schools, 4 trade schools, and 14 evening schools for adults.

The YIVO institute also went through reorganization in the spirit of the regime. The Bund and the Zionist leaders of the institute were defined as ‘Enemies of the People’, research and publications on Jewish national subjects were stopped, and the institute was mobilized to train Yiddish teachers for the Soviet Jewish educational system and was required to place its library at the disposal of Yiddish studying students in the upper high school classes. These changes altered the original Jewish character of YIVO. In January 1941 it was transformed into the ‘Institute of Jewish Culture’, an integral part of the Academy of Sciences of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic, with Noah Prylucki at its head. A chair in Yiddish was dedicated in the department of linguistics at the Vilna University. These steps surprised the Jewish public and the world. On the one hand, it was impossible to ignore the harm done to original Jewish research and publication and on the other hand the Soviets extended great help to the language and Yiddish culture, according to the well known expression ‘Yiddish culture in form and Soviet in content’.

The Jewish newspapers were also Sovietized. The ‘Vilner Kurier’ was closed. The Zionist Vilner Togblat, whose editor, Dr Wigodski was known for his Soviet sympathy, and its vigorous fight against anti-Semitism, continued to appear for a while, but on August 20, 1940 it too was closed as well and in its place appeared the communist Vilner Emes. It also appeared for a few months only. Subsequently, Vilna Jewry could only read the ‘Der Emes’ which appeared in Kaunas and provided a literary platform for Yiddish writers in Vilna. Jewish literature had a ‘Half Hour in Yiddish’ devoted to it in the official Vilna radio, 3-5 times a week.

The local theatre enjoyed a rich activity. Jewish actors, both local and from among the refugees, appeared in the framework of the ‘New Yiddish Theatre’, which was officially named the ‘State Jewish Dramatic’ theatre. It had a Jewish marionette theatre attached to it.

Great changes took place in the religious life. The authorities abolished the legal position of the rabbis in matters such as recording births or officiating at weddings and transferred these tasks to an official government office. The public nevertheless continued to require the services of the rabbis, the kosher slaughterers, mohels and other religious ministrants. A Brith Milah was done within the family circle or in the synagogue. Bar Mitzvah ceremonies were held as before. In spite of the wide anti religious propaganda and the heavy taxation, the synagogues remained open and filled with worshippers, particularly on Saturdays and festivals. Charitable and beneficiary activities took place within the synagogues. The Polish yeshivas which were officially closed by the Soviets divided off into small groups in various townships and attempted to continue to study in secret.

The Zionist organizations were disbanded and most of their members halted their activities, either because of fear of punishment or because of a genuine desire to adapt themselves to the new regime. The attempts of the members of the Bund to find a common language with the authorities was disappointing, they were presented as perpetual Trotskyite enemies of the Soviet state. A few of the Zionist youth movements organized underground activity. Their members held penetrating discussions on their ideological stance and the search for organizational means suitable for the new reality including smuggling members to the free world. A number of youth organizations connected with Betar decided, on their initiative, to disband, although the members continued to keep in touch personally. Members of Hashomer Hatzair faced a quandary either join the new regime or hold on to their independent ideology even when that involved creating an illegal organizational framework. Their efforts to receive recognition of the Hakhshara training kibbutzim failed. Members of Freiheit also faced the question as to their path. Their attitude towards the Soviet regime was more reserved than that of Hashomer Hatzair, The ‘Khalutz Coordination’ in Vilna included also the movements Gordonia, Akiva, Zionist Youth and the Hekhalutz Hamizrakhi. Members of the movements who elected to continue their activities, divided off into small groups meeting in secret in private homes. Some dispersed outside the city.

After Lithuania turned into a Soviet republic, the Jewish leadership feared the complete halting of the exit of Jewish refugees, which, by then, had already been reduced. But the international effort of Jewish elements and others made continued emigration possible by various means. In negotiations conducted in Moscow and London, the Soviet authorities agreed to permit movement through the Soviet Union of Jews holding entry permits to Eretz Yisrael or entry visas to other countries,. Between 1,600-2,400 Jews entered Eretz Yisrael through Odessa and Istanbul, a few hundred came via India and Trans Jordan, 2,000-2,200 Jews left Vilna for Moscow, Vladivostok and continued from there by sea to Suruga and Kobe in Japan, a further 1,600-2,400 people left for Moscow, and continued through Kiev to Istanbul as an intermediate station on the way to Eretz Yisrael. The remainder, at most a few hundred, left Moscow, using Laissez passer documents, for Iran and passing through Trans Jordan to Eretz Yisrael. The exit of Jews stopped in the spring of 1941, just before the decision of the authorities to grant Soviet citizenship to the refugees as well. In total, some 5,000-6,000 Jewish refugees left Lithuania, mainly from Vilna, in the period between autumn 1939 and April 1941. These emigrants were spared the fate of their brethren who remained in Vilna and in the areas under the Nazi conquest.

While permitting emigration with relative ease, the Soviet authorities also took vigorous action against what was termed political opposition and disloyal elements both among the local population and among the refugees. In November 1940 the ministry of internal affairs (the NKVD) defined the categories of the ‘Enemies of the People’: Zionist leaders and activists (chiefly Revisionists and Betar members), leaders of the Bund, Jews who had participated in the struggle for Lithuanian independence, and refugees possessing entry visas to foreign countries. All the above were listed and subject to constant surveillance. They were called in for frequent interrogation by the NKVD. In June 13-14, a week before the German invasion, some 16,000 inhabitants of Vilna and other Lithuanian places (according to official Soviet documents), among them about 3,500 Jews, were exiled to far off places in the Soviet Union. The Jewish community was severely affected. In view of the mass exile there was anticipation that there would be a show of solidarity among the affected national groups. But the reality was different. The non-Jews pointed at the presence of Jews in the NKVD ranks and the Jews as a supporting component of the Soviet regime. This attitude fed the anti Semitic feelings and had tragic consequences in the Holocaust.

The German attack and the occupation of the city, June 22-24, 1941

On the first day of the Barbarossa Operation, Vilna was bombed and the rumor in the city was that the Germans were close by and the Soviets are preparing to retreat. The Jews were in a state of panic. The following day, June 23rd, the bombing intensified and the Soviet officials, Jews among them, abandoned the city by train and other means of transport. Many others, who did not find transportation, marched on foot towards the east in the direction of Minsk. In particular, the ones who left were mainly connected to the Soviet government bodies and were afraid of revenge by the Nazis and by the local population, as well as groups of Khalutz youth. The road taken was most dangerous. Transport vehicles and columns of marchers were targets for bombing from the air. Many were killed near the city, and others stumbled on German army units who were advancing at a furious pace. Many refugees were stopped at the previous 1939 Polish Soviet border. Finally, less than 3,000 Vilna Jews succeeded in reaching the Soviet interior. Others, those who did not fall casualty on the road, returned to Vilna, already in German hands. The reasons why such a limited number of Jews made it to the Soviet Union may be that little was known of what was taking place in conquered Poland and the danger facing the Jews under German rule and the almost total absence of means of escape in view of the complete collapse of the Soviet military and civil framework.

The Number of Jews in Vilna before the Shoah

The census of 1931 gave the number of Jews as being 55,000 in a total of 195,000 city residents, and in 1937, there were 58,000 according to official statistics. After the annexation of Vilna to Lithuania, various estimates give a figure of 70,000 souls (including the refugees). During the period of Lithuanian and Soviet rule (in the years 1939-1941), some 5,000-6,000 Jews emigrated , a few thousand were exiled in the middle of June 1940 to the Soviet Union , some 3,000 fled to the interior of the Soviet Union at the German invasion, which leaves approximately 57,000 Jews remaining when the German army entered the city. They faced a new reality of a struggle for their actual existence.

Period of Military Rule-until August, 1941

On June 24, 1941, two days after the beginning of the invasion of the Soviet Union the Wehrmacht entered Vilna and set up a military government which lasted until August 1, 1941. The period of military control may be divided into two parts: 9 days of joint Lithuanian German control, from June 24 until July 2, 1941 and after that the beginning of direct German military rule. During the days of the joint rule, the Lithuanians, who were a minority in the city, attempted to establish their hegemony over the city's Polish majority. They expected the Germans to support them in their efforts as also in their plans to suppress the Jewish population. The ‘Frontas Lietuvio Aktivistu’ (LAF, The Lithuanian Activists front), which represented all the political parties active in independent Lithuania, and had kept in secret contact with Nazi Germany even during the period of Soviet occupation, hoped to lead Lithuania to full independence with the aid of the Nazis. Before the German invasion, the Front issued a proclamation in which they abolished the right of Jews to live in the land of Lithuania and demanded their immediate exit. In the beginning the German military government recognized the rights of the Lithuanians both in the state and municipal sphere, and supported them in the struggle against the Poles and to impose a Lithuanian content on the city. Although in the beginning of July 1941, the joint Lithuanian German administration was abolished, and the German military closed many of the institutions established by the Lithuanians and limited the authority of dozens others. The Germans followed a basic policy namely, to avoid giving independence to the population in the Baltic lands and the other conquered areas in the east which were to come under direct German rule. Vilna, its Jewry, and of all Lithuania fell under German civil authority within the framework of the Ostministerium (The Ministry for the East).

In the first days of the occupation, the Lithuanians were engaged mostly in their struggles against the Poles, but very soon joined the Germans in harassing the Jews, enacting anti Jewish edicts and participating in the policy of mass murder of Jews. Lithuanian ‘Partisan’ units were disarmed but reorganized as regular police formations and placed under direct German command. A few members of the interim Lithuanian government were appointed advisors to the civil governor. Although the hope of Lithuanian nationalists to attain an independent Lithuania with German help was dashed, they did not lose faith in their expectations of changes in German policy and did not break off their connection with the new ruling authorities. The collaboration of political nationalist elements and other large population groups in the murder of Jews continued.

At the beginning of the occupation the Germans tasked units in the Wehrmacht with the execution of the anti Jewish policy. These units were attached to the military city government as well as the Einsatzskommando 9 which reached Vilna on July 2, 1941. On June 24-25, 1941, 60 Jews and 20 Poles were taken hostage. The German explanation given was that this was to ensure compliance with their orders, Until July 22, 1941 the Jewish hostages were kept in the Lukiszki prison (in Lithuanian Lukiskis), only six were freed, the remainder murdered. On July 26, the kidnapping of Jewish men for forced labor began. Many of the men did not return home and later it transpired that they were executed. Lithuanians and Germans breaking into Jewish homes for plunder became a common occurrence. Jews were thrown out of their jobs, chased out of the queues waiting at the food shops, and on July 5th separate food shops were set aside for them, and permission was granted to buy in the markets only in the late evenings when most of the fresh produce had already been sold. Travel on public transport and walking in the main streets was forbidden. According to an order issued on July 3, Jewish men and women of all ages were obliged to wear, a yellow badge, of 10 centimeter diameter, on the front and back of their clothes. A few days later, the order was changed obliging everyone, over 10 years of age, to wear a white armband on the sleeve 10 centimeters wide with a Star of David imprinted on it. Wehrmacht soldiers and Lithuanian police continued to snatch Jews off the streets for work in the army camps and suchlike while cruelly maltreating and degrading them. The plunder of Jewish property became systematized. Large businesses and industrial plants had already been nationalized under the Soviets, and after the German conquest the Lithuanians began to confiscate the small plants, workshops and shops that still remained in Jewish hands. The Jews were accused of hiding goods and rioters searched their homes, while stealing valuables and household articles. According to an order issued on July 21, Jews were forbidden to sell or transfer property to others or to change their abode.

At the beginning of July 1941 the Germans decided to set up a Judenrat (Jewish council) in Vilna. On July 4th, German officers of the military government searched for the community rabbi, and as he was not found, they placed the task of forming a Jewish representation within a day on the synagogue beadle, Haim Meir Gordon. The beadle reported this to a number of public personalities and a number of community activists. Rabbi S. Frid and the Zionist leader Dr G. Gershoni requested elucidation of this order from the Lithuanian authorities. The Lithuanians, who had hoped to have Jewish affairs left in their hands, replied that the Jews are expected to choose a representation of 10 members who would deal with them only and avoid any connection with the Germans. Dozens of public personalities from every shade of the political spectrum met that evening. In the meeting they heatedly discussed the creation of a Jewish representation. Dr Gershoni spoke with feeling of the difficult situation in which the community found itself and the need, especially in this fearful hour, of appointing a responsible and devoted committee. The delegates knew only too well that the framework for the establishment of the committee was being dictated by the Germans and that it would have to function under conditions hitherto unknown and not experienced. Not everyone was convinced by the excited speech by Dr Gershoni and his compatriots, and strong moral pressure was needed to convince them to assume public responsibility. The first Judenrat numbered 10 members, each of them a known figure within the community and among the various political groupings in the Jewish quarter. The Jewish public saw in the Judenrat their trustworthy representative which would work to ease the burden of the oppressive orders and represent their interests. Sh. Trotski was elected chairman with Antol Frid his deputy. Dr Ya'akov Wigodski, the well known leader who was active before the war in the anti Nazi struggle was not appointed to the first Judenrat out of fear that his public appearance would attract German attention and he would be harmed by them.

Immediately after its establishment the Judenrat attempted to deal with the most difficult of anti Jewish persecutions, such as the abduction of Jews for forced labor, or the expulsion of Jews living in the high streets from their homes. In order to halt the arbitrary abduction of men from the streets and their homes, the Judenrat took upon itself the task of providing the forced labor demanded by the Germans on a daily basis and evenly applied.

The first Judenrat as originally constituted did not last many days. In an order on July 15, 1941, the German governor of Vilna demanded it be enlarged to 24 members. The discussions and arguments on the character and tasks of the Judenrat and actual participation in it were renewed with the publication of the order. The anti participation delegates argued that the Judenrat was but a means in the Nazi hands to further oppress the Jewish people, whereas the ones favoring its existence saw its importance as a loyal and experienced national representation able to face the Nazis and the Lithuanians and alleviate, albeit a little, the worst of the distressing situation. The enlargement of the Judenrat was completed on July 24, 1941, and it largely represented the various political and social groups, excepting the Communists and the Revisionists. Among the members were the previous community head, Dr Ya'akov Wigodski, the jurist Shabtai Milkonowicki, and the Bund leaders Grisza Jaszunski and Yoel Fiszman. The enlarged Judenrat was indeed trusted by the public, who saw in it a loyal and efficient representation who struggled in their interests.

Mass Murder in Ponary

In anticipation of the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Nazi headquarters allocated the leading role in the elimination of the Jews in the conquered areas to the Einsatzgruppen and the Einsatzkommando units, while depending simultaneously on the collaboration of the local population. From July 4, until August 9, 1941, the task of murdering the Jews in Vilna was placed upon Einsatzkommando 9, belonging to the Einsatzgruppe B. The unit entered the city on July 2, 1941, and on their way they added a section of the German Police (ORPO). After two days of organization they began organized killings. In addition, 150 Lithuanian policemen and members of gangs were mobilized (Lithuanian nationalist anti-Soviet partisans secretly assembled in anticipation of the Nazi invasion).The extermination was conducted in a single continuous action: Jews were taken off the streets or from their homes, imprisoned in the Lukiszki prison, and from there taken to the Ponary killing fields and executed.

In Ponary, a wooded area some 10 km. south of Vilna, the Soviets had dug huge pits for the storage of fuel containers. The dug out earth was laid around it in a high embankment and hid the ditch from sight. The Einsatzkommando with their Lithuanian collaborators chose Ponary as the suitable site for their mass murders.

The prisoners were kept in the Lukiszki prison for periods which stretched from a few hours to a few days, in accordance with the absorption ability of the killing site. Once at Ponary, they were first taken to the waiting area, a few hundred meters from the ditches, there they were registered, forced to undress and to hand over their valuables. They had their eyes covered with bits of clothing, and then marched in line to the ditches. When standing in front of the ditches machine guns opened fire on them and then the bodies were flung into the ditches, often wounded ones or unharmed in body. After some time, the machine guns were changed to rifles to ensure better marksmanship. If the shooters noticed someone moving within the ditch, a further shot ensured the kill. The victims were covered with a thin layer of sand and then the next group of Jews was brought to the place. The murderers kept improving their system and achieved a kill rate of 100 persons per hour. At various times, Soviet prisoners were also executed in Ponary. It should be noted that the Einsatzkommando 9 murdered Jews outside Ponary as well. On July 11, for instance, they shot dead dozens of Jews in the approaches to the city in retaliation for shots fired at German soldiers from an unidentified place.

In July 1941, the Ponary victims brought via the Lukiszki prison were mainly forced laborers picked up on their way to or from work. The Judenrat now faced a difficult dilemma: when it took upon itself the task of providing forced laborers in order to stop the random abductions off the streets, they did not know what had happened to the men who had disappeared. As time went on, the anxiety grew as to the fate of these men, and it quickly transpired that the organized groups of laborers were the target of the Zonderkommando and its local collaborators.

It should be noted that the German military and civil administration as well as the Lithuanian one were not at ease with the activity of the Sonderkommando, mainly as this interfered with the regular supply of Jewish labor to industry and services. The Judenrat exploited this difference of interests between the various German authorities and requested of the employers of the Jews in the army camps and other essential services to provide their workers with passes (Scheine) which should stop them from being kidnapped in the streets. These efforts were successful and the authorities did indeed issue such passes but the murderers did not always respect them. At first, Einsatzkommando 9 concentrated on hunting down men only, both because it would hide the intention behind their actions (the explanation given to the Jews was that the men were sent to work in remote places) and also to eliminate that part of the population who may become a danger in the future. Besides the random kidnapping it was obvious that there was a systematic hunt for political leaders, rabbis and members of the cultural elite. Lithuanian police units subservient to the Einsatzkommando 9 were given orders to prepare lists of Jews belonging to these categories. The early elimination of the leadership and elite was intended to break Jewish resistance and ease the carnage work. The Einsatzkommando did not always work by the book in Vilna in systematic finding and killing special selected groups. At times they snatched Jews randomly and for no apparent reason, whereas on other occasions they carefully collected the victims from lists prepared beforehand. At dawn on July 14, for instance, the Germans and Lithuanians collected rabbis from their homes according to a previously prepared list. Later on, as is known, women and children were also taken and killed.

In the period July 4-20, 1941, approximately 5,000 Jews were executed in Ponary by Einsatzkommando 9 and their Lithuanian collaborators. Afterwards most of the members of Einsatzkommando 9 left Vilna for the east in the direction of Minsk. The remaining group continued in the city until August 9, 1941, and continued its murderous activities, though on a reduced scale. Their place was taken by Einsatzkommando 3 of the Einsatzgruppe A.

Lithuanian Units Participating in Arresting and Murdering Jews

The German authorities changed the Lithuanian law-and-order units into police battalions (Pagelbines Policijos, Tarnybos Battalionas), and these were vigorously used against the Jewish population over a long period and tasked with mass murder. A central role in the enforcement of the Nazi anti Jewish policy was fulfilled by the Security Police (Saugumas) commanded by Aleksandras Lileikis and his deputy Kazys Gimzauskas. They had under their command a body of some 100 policemen in civilian dress who searched for hidden Jews, and while the ghetto still existed, prevented attempts at breaking out and further attempted to stop the issuing of false documents to prove that the bearer is not a Jew. They were also active in handing Jews over to the Lithuanian murder squads ‘Ypatinga Burys’ which were active in Ponary. The Lithuanian Security Service, ‘Tautos Darbo Apsaugas Battalionas’ which was composed of over one hundred men, and was under the command of Martin Weiss and August Herring of the German Security Police, were responsible for the transport of the prisoners from the Lukiszki prison the killing grounds, guarding them before the killing, and guarding the area while the ‘Ypatinga Burys’ carried out the murders, and after the deed covered the ditches with soil. Their commander was a Lieutenant, Balys Norvaisa with Balys Lukosius second in command, who was later replaced by Sergeant Yonas Tumas.

|

|

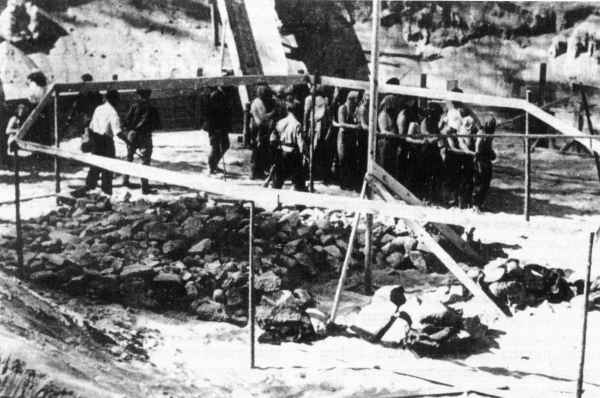

| The killing fields at Ponary near Vilna Source: Yad Vashem photo archives |

The Period between the Establishment of the Civilian Administration until the Creation of the Ghetto on September, 1941

The city administration passed from the hands of the German military to the German civilian rule on August 1, 1941, by the ‘Fuhrer's Order’ of July 17, in the matter of political administrative arrangements in the eastern conquered areas. Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and parts of White Russia were included in the Reichskommissariat Ostland, with a further subdivision into Generalkommissariat (provinces) and Gebietskommissariat (counties). Lithuania became a province divided into five counties, one being the city of Vilna.

With the appointment of the SS as the security authority in the area, it was in fact established as the supreme power over the civilian and economic authorities and strained the relationships between the various arms of the German administration. The multiplicity of authorities caused a plethora of regulations regarding various activities including those affecting the Jews. Thus for instance, the Wehrmacht stores were tasked with the production of equipment and other necessities needed for the front. Military men ran plants and workshops and were interested in utilizing local skilled labor, including Jews. The SS officials and other factors in the civil administration, on the other hand, looked askance at the intervention of the army in dealing with the Jews. By the end of July 1941 a General-kommissar was appointed to the General-kommissariat, Otto von Renteln, who had his seat in Vilna. With the setting up of the German civil authority, the Lithuanian institutions having national state functions were dissolved.

The German civil administration, the Gebietskommissariat Vilna, set a number of essential goals before itself: the imposition of law and order in the city, maximum exploitation of local labor for the German war effort and the prevention of enemy activity against the rule of the conquerors. Its broad powers included dealing with the Jewish problem. The Brown Folder prepared at the beginning of September 1942, by the Ostministerium, contained basic instructions for administering the area in general including directives for dealing with the Jews. The overall responsibility for dealing with the Jews in Vilna was placed upon the governor (Gebietskommissar) Hans Christian Hingst. Franz Maurer, his assistant, was in charge of Jewish affairs. The executors of the Jewish policy were in direct contact also with the police HQ and the SS and with the police security units and the SD among them the Gestapo IV section.

August 1941 Edicts

On August 6 the Vilna Jews had a 5 million Rouble fine imposed upon them. Franz Maurer ordered 3 members of the Judenrat to his office and demanded that by 9 o'clock the following morning, they were to deliver 2 million rubles and the remainder during the rest of the day. He threatened that if they do not appear with the first payment as demanded they will be executed. The frightened Jews organized street and area committees for the collection of the money. The response to the Judenrat appeal to donate money and valuables was generous but the full sum was not achieved in the time limit and Maurer, who was not satisfied with the partial payment, continued to threaten. At the beginning he refused to extend the time limit for making the payment, but eventually he relented and allowed the continuation of the collection, and the members of the Judenrat who had been taken hostage were released. The ransom was collected within a few days and the Germans received some 1.5 million Roubles, about 16 kg. of gold and many watches.

On August 12 Gebietskommissar Hingst issued a decree which contained many regulations: Jews were forbidden to buy in the market place during the daylight hours, dire punishments for dealing in the black market, curfew during the night hours, confiscation of all sorts of vehicles etc. The murders continued during August 1941, although in smaller numbers than in the previous month. According to the reports by Einsatzkommando 3,144 Vilna Jews were killed in the days between August 12 and September 1, but it is possible that the real number was greater.

During the summer Vilna Jewry came to the conclusion that the main chance of immunity lay in working for the Germans or the Lithuanians, who needed Jewish labor (it must be remembered that at that time the bitter fate of the ones taken to Ponary was as yet unknown). Jews who received Scheine from their workplace felt relatively safe and everyone anxiously searched for workplaces which issued such Scheine, and these were occasionally respected by the Jew hunters. At a later date, the Judenrat too came to this conclusion for saving people, albeit only partially, by working for the German economy, and a separate Judenrat department allocated labor as demanded. The Germans and the Lithuanians handed their demands for workers to the Judenrat and these were immediately supplied. Many Jews found a workplace directly, not through the Judenrat, but rather by personal connections or by bribing employers. In addition to the Scheine, the work also provided opportunities to meet non Jews and buy foodstuffs, thus easing the hunger reigning in the ghetto.

Dr Ya'akov Wigodski, one of the outstanding leaders of Vilna Jewry, died in August 1941, aged 86. From the very beginning of the conquest he stood out by his dignified attitude to the German pressure and served as an example for other public figures. He tried to prevent the members of the Judenrat from sending workers for labor outside town without knowing what will befall them. He was arrested on August 24 by the Germans, possibly because they did not relish his courageous stand. Dr Wigodski was already ill during his imprisonment and the harsh prison conditions hastened his demise. His death was a heavy loss to Vilna Jewry, who was much in need of great leadership in those distressing days.

The Great Provocation

In the days between August 31 and September 3, 1941, 8,000 Jews, men, women and children were murdered in Ponary, in an act that was named ‘The Great Provocation’, which was connected with the preparations for the creation of the ghetto in Vilna. On August 31, two Lithuanians entered a house inhabited by Jews and fired on a group of Germans who were milling around in the square outside a cinema. The two conspirators quickly disappeared and the Lithuanians accused the Jews of the act. They themselves, together with German soldiers, broke into the house and killed two Jews who were accused of the assumed deed. Immediately after that, the kidnapping of Jews in the area intended for the ghetto began. Work Scheine were not honored, and their owners were included among the kidnapped. The Jewish population was placed under curfew to facilitate the kidnapping. People were taken out of their homes by the Germans and the Lithuanian collaborators and concentrated in the Lukiszki prison. This place, which already had a history of malevolent treatment by the Lithuanian guards in July, once again became a place of robbery and ill-treatment by the Lithuanian guards. The prisoners were taken to Ponary on foot or by truck, taken to the ditches in groups of ten, shot by the Lithuanians (under German command), and fell into the pits. Some were only wounded and were buried alive. Six wounded women managed to crawl out of the pits in the dark and with the help of local peasants returned to Vilna and were hospitalized in the Jewish hospital. The Vilna Jews learned from them, for the first time, of the horrors of Ponary. In this Aktzia the members of the Judenrat were also killed. On September 2, in the course of the kidnappings, a member of the SS, Horst Schweinberger, entered the offices of the Judenrat and took with him 16 out of the 22 in the place, 10 of these were members of the Judenrat including the chairman, Shaul Trotski. They were all taken to Ponary and murdered. The Germans did not touch four other members of the Judenrat in the office: deputy chairman Anatol Fried, A. Zeidsznur, Grisza Jaszunski, and Yoel Fiszman.

In the first days after the Aktzia, with rumors of the erection of the ghetto in the background, the remaining members of the first Judenrat with other Jewish activist figures kept in touch with the Lithuanian city authorities in an attempt to find out what was intended to be the future policy. But the Lithuanian officials had no influence whatsoever on the Nazi policy vis a vis the Jews.

The Establishment of the Ghetto

The preparations, both practical and ideological for, the establishment of the ghetto, were set in action before the ‘Great Provocation’.

|

|

| Map of Vilna Ghetto |

In a document dated August 18, 1941, the German Ostland administration detailed the basic policy regarding the Jews: the establishment of ghettos in the areas holding a Jewish majority, forbidding Jews from leaving the ghettos and providing a minimal food supply (enough to keep alive), the setting up of an independent Jewish administration in the ghetto with a Jewish police force to keep order, the isolation of the ghettos from the outside world by cutting off mail and phone connections. During August 1941, the local German administration decided to establish a ghetto in the city in keeping with these principles.

The Great Provocation was but a small Aktzia in this policy, meant to reduce the Jewish population in the area intended to serve as the ghetto and to enable to the Germans to squeeze into it the Jews from the other parts of the city. The Germans decided to set up two ghettos: Ghetto A, the large one, based on the streets Straszun, Oszmiana, Yatkever, Rudnicki, and Szpitalne. Ghetto B, the small one, based on Zydowska (Yiddishe Gas), Szklara (Glezer) and Yatkever streets. The transfer to the ghettos was put into the hands of Lithuanian police units.

On September 6, 1941, the city Jews were ordered to remain in their homes and were forbidden to leave for their work. The move from the houses began and was carried out with great cruelty. The Jews were permitted to take with them only as much as they could carry. During the day the Germans changed the direction of the ghetto by adding or subtracting streets in whole or partially. Thousands of Jews were not transferred to either of the ghettos but were taken directly to the Lukiszki prison. A few hundred workers, possessors of Scheine from work places, proving that the are essential workers, were returned to the city, whereas the others, estimated at 6,000 souls, were brought on September 10 and September 11 to Ponary, their property was confiscated and they were executed. The remaining Jews were forced into the two ghettos some 30,000 into Ghetto A and 9,000-11,000 into Ghetto B. Many died shortly after the transfer as a result of maltreatment or because of the difficult conditions.

The transfer of the Jews to either of the ghettos was random, without any consideration as to their belonging to any particular part of the population, but it soon transpired that the Germans had a specific purpose for each ghetto. On September 15, they began to transfer people who did not work-the elderly, the sick and orphan children in the orphanages, from Ghetto A to Ghetto B and Scheine possessors with their families from Ghetto B to Ghetto A. On September 15, some 3,000 residents of Ghetto A who did not possess Scheine were moved to Ghetto B. As they left Ghetto A, some 2,400 were taken to Ponary and murdered there and then and about 600 were put into Ghetto B. It was said that this was done to hide the German intention to eradicate Ghetto B earliest. The inhabitants of Ghetto B soon became aware of the German program and began surreptitiously to infiltrate back into Ghetto A.

The forced abrupt congestion of thousands of Jews in a small area created a housing crisis. Every room, corridor, storeroom, attic and basement turned into living quarters and many were left out in the courtyards under the open sky. Before the transfer to the Ghettos, as mentioned, the first Judenrat was executed, and in the absence of a guiding body to allocate living space, violent elements took possession of property and housing of victims taken to Ponary. In the first days, in addition to the terrible physical conditions and the economic distress, a heavy feeling of calamity descended upon the inhabitants of the Ghetto: many now occupied the apartments but recently emptied of those taken to be murdered in Ponary.

On September 7, the day after the transfer, the Germans created a separate Judenrat for each Ghetto. Antol Frid, deputy chairman of the first Judenrat and a survivor of the ‘Great Provocation’, was ordered to form a new Judenrat in Ghetto A. He included three survivors of the previous Judenrat Grisza Jaszunski, Yoel Fiszman, Szabtai Milkonowicki, and G. Gochman connected with the Bund. The shock of the past weeks' events destroyed the belief in the Judenrat, and Antol Frid labored hard to renew the public support and faith in the Judenrat. A few public figures promised to assist the new Judenrat, which had begun its activities under more difficult conditions than its predecessor. The Judenrat in Ghetto A consisted of five departments in the beginning a food department under Jaszunski, a health department under Milkonowicki, a housing department under Gochman, a labor department under Yoel Fiszman who was also responsible for relations with Ghetto B, and administration headed by Frid himself. The Germans also formed a Judenrat in Ghetto B consisting of five appointees, headed by Isaac Leibowitz, his colleagues were unknown to the public and subsequently, Leibowitz formed an unofficial leadership of a few known and respected people. The Ghetto B Judenrat was divided into departments similar to those in Ghetto A. The Ghettos had a joint department of education under S. Gezundheit.

The underlying reason for the erection of the ghettos was the German program to limit the Jewish population through starvation and the creation of intolerable living conditions. The Judenrat and the activists assisting it did their best to maintain minimal living conditions for the Jews and thus enable them to survive. Their first consideration was the easing of the hunger which reigned throughout the ghettos and the prevention of plagues. Ghetto A saw the establishment of a hospital and both ghettos had clinics and sanitary services. The medical staff, doctors and nurses, treated the sick with extraordinary care, despite of the shortage of equipment and medicines. The food department shared out the foodstuffs brought by the Germans into the ghetto, made efforts to acquire additional food from elements outside the ghetto and opened public kitchens. The housing department did its best to bring order into the allocation of living space and took care of those who were living in the open in the streets and courtyards. The Judenrat also paid attention to education and opened schools and libraries. Ghetto A had some 3,000 registered pupils at the end of September 1941. Special frameworks were established for orphaned children whose parents died in the mass executions. The employment office provided laborers to meet the German demands. Despite the hard and demeaning work in many places, the Jews acknowledged the importance of the work and continued to consider the Scheine issued to the workers a sort of guarantee against falling victim to an Aktzia.

A special role in the Vilna ghetto was played by the Jewish police. Immediately after the completion of the transfer to the ghetto, the Judenrat published, under order of the Germans, a call to the young Jews to join the ranks of the Ordnungsdienst (Security service). Preference was given to ex servicemen, officers were given command. Frid appointed Ya'akov Gens, an ex officer in the Lithuanian army commander of the ghetto police (Later on, Gens had a central and contentious role in the Vilna ghetto). His deputy, Yosef Muszkat, a lawyer, was a refugee from Warsaw, who arrived in Vilna in the autumn of 1939. Gens, Muszkat, a few other officers in the police and many of the policemen were in the past members of the Revisionist party and Betar organizations which had more ex army personnel and officers than other groups. It is reasonable to assume that Gens and his officers accepted into the police ranks men known to them personally. A struggle took place in the ghetto as to the public function of the police. The Bund members of the Judenrat took exception to the fact that the police was run by members of Betar, and introduced their own man, Herman Kruk, into the top echelon, but he did not find himself at ease within the police. Tension existed between the Judenrat and the police. Ghetto B had a separate police force. The Judenrat appointed the lawyer Fabiarski commander. In the second ghetto the Judenrat exercised control over the police and unlike the police in Ghetto A, it did not have a party coloring. In both ghettos the Judenrat saw the police forces they established as bodies which were meant to secure the population struggling for its survival and provide essential basic services.

The Yom Kippur Aktzia on October 1, 1941

On October 1, at noon, Germans and Lithuanians broke into Ghetto B and the seizures began. The synagogues, filled with worshippers, were the first targets. Within a short time, 800 Jews were collected and taken out of the Ghetto. After an interval of a few hours, the pursuit was renewed and another 900 were taken. That day, the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators took some 1,700 Jews to the Lukiszki prison. The Aktzia came as a surprise and there was initially no difficulty in seizing Jews, but in the afternoon many tried to hide and the pursuers had greater difficulty in finding them.

The Judenrat and the Jewish police in Ghetto B were not required to participate in any way in the Aktzia. The opposite was the case in Ghetto A. There the Germans demanded that the Judenrat bring one thousand Jews without Scheine to the Ghetto gate before evening. They threatened that if the demand was not fulfilled, they would enter the Ghetto and gather the Jews by themselves, as they did in Ghetto B. Not having a choice and after much hesitation the Judenrat decided to gather the people using the Jewish police for this. The Jewish police announced throughout the Ghetto that anyone without a Scheine should present himself at the Ghetto gate, but by the appointed hour only 46 men appeared. The Germans retaliated by commanding all the Ghetto Jews without distinction to immediately gather at the gate and announced that they will choose the victims themselves. They immediately entered the Ghetto and assisted by the Lithuanians pulled people out of their houses. The Scheinless men suspected the worst and hid whereas many owners of Scheine did appear being certain of their safety. Some 2,200 Jews gathered at the gate and all were taken by the Germans and Lithuanians to the Lukiszki prison.

|

|

| Program of shows by the Vilna Ghetto Theater for 1943 Source: Yad Vashem photo archives |

The Jews from both the Ghettos were kept at the Lukiszki prison until October 2. A few hundred were freed thanks to the intervention of representatives from their work places, who requested that high priority essential workers be freed. A few dozen more were freed thanks to personal connections or bribery. All the others were taken to Ponary and killed.

All the sources at our disposal show that the Yom Kippur Aktzia signaled a change in the attitude of the Judenrat towards the German demands: until that date the Judenrat fulfilled demands relating to the economy and the supply of workers only, but in the above Aktzia they crossed the line and consciously participated in the collecting of people and handing them over, in spite of being well aware of the fate awaiting these outside the Ghetto. Thus, the Judenrat laid down a new rule: foregoing some of the Jewish population in order to save others. This behavior brought about bitter arguments within the Judenrat and among the Ghetto inhabitants. The head of the Judenrat, Antol Frid and the chief of the Jewish police, Gens, overcame the opposition to this policy but the price was the creation of a gulf between the Judenrat and the Jewish police and large sections of the Jewish public. In October 1941, organized opposition to the policy of the Judenrat did not appear as yet.

After the Yom Kippur the belief was strengthened among large sections of the Jewish populace that safety lay only in working in secure places and the holding of a Scheine was the only way to save life.

The Liquidation of Ghetto B

Following the Yom Kippur Aktzia, further Aktzias followed quickly, and by October 21, 1941 the Ghetto was completely liquidated. In the night between October 3-4, a further 2,000 of its inhabitants were sent via Lukiszki Prison to be murdered in Ponary. The cover story told by the Germans to avoid opposition was that they were being sent to another ghetto in the area which was short of working hands. Most of the Ghetto B residents, who were not part of the working population and who feared for their lives, seized this story like a drowning man holding onto a straw, and willingly responded to the German call to report. That night an unusual event occurred: a group of Jews noticed that they were being led in the direction of Lukiszki prison. The men lay down on the ground and refused to move. The Germans opened machine gun fire at them and some dozens were killed on the spot. Others succeeded in escaping, but as they didn't find shelter outside the Ghetto they infiltrated back again. The researchers see in this event the first passive mass opposition by the Vilna Jews.

On October 15-16, the days of Simkhat Torah and Succoth's Isru Khag, an additional Aktzia took place when 3,000 Jews were led to Ponary and there were put to death. Ghetto B now held less than 4,000 Jews. Filled with growing fear and the expectation of the imminent liquidation of the Ghetto many attempted to steal across to Ghetto A. The final Aktzia in Ghetto B took place on October 21. Germans and Lithuanians inspected thoroughly each house and each possible hiding place. Hundreds who had prepared themselves hiding places were discovered and led to Ponary with all the others. The bloody harvest totaled over 2,500 souls. Individuals remained concealed in hideouts (Malinas), and later infiltrated by various means into Ghetto A. The Germans transferred to Ghetto A groups of Jews useful for work. This brought to a close the tragic saga of Ghetto B.

Continuation of Mass Murder in Ghetto A

The hunt for Scheineless Jews was renewed in the first Ghetto, while organizational changes took place in the organization of the supply of Jewish Labor. In the first months, a number of German and Lithuanian authorities dealt with the matter of Jewish labor, but from October 1941 the German Labor Office at the Gebietskommissariat in Vilna dealt with the requests for workers, their placing in various work places and the issuing of Scheine. The certificates issued by work places were cancelled and only the new Scheine issued by the Labor Office were now valid. The color was yellow and three close family members were included in it. The term ‘Yellow Scheine’ became of great importance in the following events in the Vilna Ghetto, and the registration anew of employees in workplaces about to issue the new Yellow Scheine created much tension in the Ghetto. The employers, including German army units were requested to supply to the labor Office lists of Jewish Labor needed. Hopes were raised again that the lucky holders of Scheine and their families would have immunity from Aktzias. Many tried by all means to be included in the lists of essential workers, either through personal connections or by bribing the foremen or the employers. The German Labor Office issued over 3,000 Yellow Scheine, and some 400 were handed to the Judenrat to be given to its employees. Out of about 28,000 Ghetto residents, only 3,000 workers and 9,000 family members, 12,000 all told, saw themselves as temporarily safe. The Ghetto became a seething place of thousands without Scheine who turned their anger against the Judenrat which had received 400 Scheine for its employees. The request by the chief of the Jewish police, Ya'akov Gens, for the Germans to grant employees of the Judenrat and public bodies in the Ghetto extra Scheine was refused. In order to exploit to the full the possibilities latent in the Scheine, false registrations of weddings took place in the Ghetto, and women and children were added to bachelor worker's records.

On October 23, 1941, the Jewish police published an order demanding owners of Yellow Scheine to register that very evening with the Ghetto police in order to receive blue tickets for their families. Before dawn, large German and Lithuanian forces encircled the Ghetto. Residents without Scheine made frantic efforts to find hiding places in the Ghetto and some even broke through the fence in their efforts to find some refuge outside. Early in the morning the Jewish police called out to the owners of the Yellow Scheine to report, together with their families, at the gate to leave for work outside the Ghetto. The Judenrat employees, together with their families, were ordered to assemble in the theater hall near the Judenrat building. Germans and Lithuanians carefully inspected each house and possible hiding places. Many bunkers were discovered and whoever refused to come out was shot on the spot. The hunt in the Ghetto continued all day, and 5,000 Jews were brought to the Lukiszki prison, all to be murdered in Ponary within two days. The workers, together with their families, remained at work that day, and returned to the Ghetto in the evening. On the morrow after the Aktzia, the Germans published a notice to the Scheinless inviting them to move over to Ghetto B where they will continue their existence and even promised to find them work. Some 1,500 were deceived into believing the Germans and moved to Ghetto B. On October 29, they were taken to Ponary and murdered.

Despite the German and Lithuanian efforts to deceive them, thousands of Jews without Yellow Scheine remained in Ghetto A after the October Aktzia. On November 3, the Germans ordered the Scheine owners to move to Ghetto B together with their families for three days, after which they will be returned to their homes in Ghetto A. While passing from Ghetto to Ghetto the Scheine were carefully inspected and anyone whose Scheine did not appear to fit the details was set aside. The Judenrat workers were also transferred together with the other Scheine possessors from Ghetto to Ghetto and Ya'akov Gens together with his men checked them during the passage. There are differences of opinion as to the behavior of Gens and his men in this affair: critics blame them for separating children from their parents and thus sealing their fate, whereas his defenders tell of him adding orphan children to families with Scheine and thus saving them from certain death. In the meantime the Lithuanians, under German eyes, combed the Ghetto A and searched for anyone secreted there. A number of bunkers were detected, in spite of their being well camouflaged: dozens of Jews found there were immediately killed. On October 5, the Scheine owners were returned to Ghetto A and many Jews who had hidden in Ghetto B joined them. About 1,200 ‘illegals’ were caught at the gate to Ghetto A, transferred to Lukiszki prison and executed a few days later in Ponary.

By the end of the Aktzia 12,000 souls remained in the Ghetto, possessing yellow Scheine and a further 8,000 Jews without Scheine. Leaving for work began again, but the allocation of housing was changed. Workers in the security depots (called the Gestapo workers), workers in the captured arms stores and workers in the military hospital were housed in three separate housing blocs, and near a few plants housing blocs were raised for the workers. The Judenrat was convinced that the separation of the workers in housing areas would strengthen the image of the ghetto as an essential productive unit, and assisted this process. The Jews who did not work and lived illegally in the Ghetto saw this as a dangerous move and great tension was created in the Ghetto as a result.

In the night of December 3, some 70 Jews, members of the underworld, were arrested. On December 4, some 90 Jews having a criminal record were arrested and taken out of the Ghetto. The arrests were made by Lithuanian and Jewish policemen according to lists prepared by the Judenrat, seemingly to rid the place of unsavory elements who might spoil the image of the Ghetto in the opinion of the Germans. Be that as it may, the fact remains that this was a planned precedent in which Jews were handed over to the Germans by the Jewish police.

Jews employed in service work at the various security services (who were called, as mentioned above, Gestapo workers), enjoyed a number of advantages. They were permitted to register in their Scheine, in addition to wife and two children up to age 16, their parents, brothers and sisters. In the Ghetto they lived in two separate blocs. Their extra rights were envied by many and the demand was great for work in these places. But soon it transpired that the extra immunity was a fiction. In the night between the 15th and 16th December, 1941, all the Gestapo workers and their families were commanded to leave the Ghetto. The people did not suspect anything, quite the contrary. They assumed that something was about to happen in the Ghetto and their employers were ensuring their safety. They were taken to Lukiszki and there they learned that only 200 from amongst them would be returned to the Ghetto and their previous employment. The remaining 300 were taken to Ponary.

Approximately 1,000 Jews worked in the Kailis fur plant producing for the German army. The plant was outside the Ghetto and the workers with their families lived in a number of houses nearby in a kind of work camp. The plant manager, Oskar Glick, was a Vienna Jew posing as an Aryan under false papers. In January 1942 a fire broke out in the plant, and in the investigation by the security services his real identity was revealed and he and his wife were executed.

After the many Aktzias, the Germans knew, nevertheless, that there were thousands of ‘illegals’ still left in the Ghetto. The Judenrat and the Jewish police were aware of the danger and searched for ways and means to legalize all or at least, some of them. The Germans on their part exploited the efforts of the Jews to achieve immunity as a means to sow illusion among the Ghetto inhabitants and thereby dull their awareness of the process of extermination. This happened with the affair of the Yellow Scheine. From the beginning of December 1941 the Jewish police issued Pink cards to family members of holders of Yellow Scheine (who had received blue cards on October 23, 1941, as mentioned above), as well as to professionals among the ‘illegals’, to past public leaders, rabbis and members of the elite. The issuance of the Pink cards was completed by December 20, and immediately after that, Germans and Lithuanians entered the Ghetto and caught anyone without a Yellow or Pink Scheine. The inspection continued until December 22. Hundreds of Jews hid, but despite the improved camouflage efforts many bunkers came to light. The concealed in a bunker in 13 Szpitalne Street refused to leave when discovered and attacked the Lithuanians. Two youths from the bunker, Moshe Hauz and Barukh Goldstein, died in the fighting. 400 Jews found in hiding places were sent to their death in Ponary. The Pink cards Aktzia completed one of the tragic chapters in the Shoah of Vilna Jewry: out of 57,000 Jews in the city at the beginning of the German occupation, 34,000 were murdered by the end of 1941. A further 3,000 Jews escaped to White Russia during the Aktzias, where Jews still lived a relatively quiet life, or found shelter outside the Ghetto, mostly under assumed identity and with false Aryan papers. Some 20,000 ‘Legal’ and ‘illegal’ Jews remained in the Ghetto.

Ways of Dealing with the 1941 Aktzias

The fact that by the end of 1941 some 60% of Vilna Jewry found their deaths by the various mass Aktzias raises a number of fundamental questions: how did the Jews understand the Nazi policy towards them? did they take in the possibility of complete extermination, or was it that they believed that such a horror after each Aktzia would not be repeated? When did they learn the truth about Ponary? How did they relate to the misleading Nazi policies and the separation of essential workers from the other Ghetto residents? What possible realistic means of defense did the Jews possibly have to oppose the Nazi war machine, considering the animosity of wide sections of the population in the city and the vicinity? We shall try to answer these questions one by one.

In the first months the Jews had no knowledge of the executions taking place in Ponary, and they mostly believed that the missing persons had been taken to work somewhere else, but as time went by, more and more rumors were heard of the events in the killing fields of Ponary. At the beginning of September 1941, with the return of six wounded women from the Ponary death pits, the first parts of the bitter puzzle came to light. The stories of the escapees from the death pits did not reach the public the Jewish doctors who tended them kept the news from spreading in the fear that the Germans would harm these survivors in order to silence them, whereas those who did have the facts given them, among them public figures, found it difficult to accept the facts and to comprehend the full implications of the horror of Ponary. In October a few more women who had escaped from Ponary returned to the Ghetto. The Jewish police warned them not to speak of what they had experienced and seen, fearing that their story would bring a disaster on the Ghetto. The bewildered Ghetto residents could not ignore the partial news about the events in Ponary, but they found it difficult to believe that it is possible for mass murder without distinction to really take place.

The Judenrat and the HQ of the Jewish police held deep and thorough discussions as to the attitude to be adopted in view of the proven knowledge of the murders in Ponary. The head of the Judenrat, Antol Frid, was of the opinion that it was impossible to prevent the extermination of a part of the Jewish population, but also that it may be possible to save some by having them employed in essential German plants serving the war machine and thus keeping the Ghetto alive as a ‘Working Ghetto’. The workers, possessors of Yellow and Pink Scheine agreed with this perception of their situation. Some Scheinless persons attempted to hide in various bunkers in the Ghetto or with non Jews outside by posing as Aryans holding false papers. During the Aktzias there were a few incidents of spontaneous opposition, mostly by individuals.

The Relatively Quiet Period, from the Beginning of 1942 until 1943

For a period of over one year no mass Aktzias took place in Vilna, although the murder of individuals and the killing of the elderly and sick continued in Ponary. The death sentence was imposed on Jews caught outside the Ghetto without the appropriate documentation, on smugglers of food, on Jews who tried to live outside the Ghetto using false papers and a borrowed identity, and on others who disobeyed the various orders of the German authorities.

On July 17,1942 the Jewish police, acting on German orders, collected a group of the elderly, the sick and invalids, and brought them to the Ghetto prison, and then to the disused convalescence home of the Women's Health organization in nearby Pospieszki. On July 22 a further 40 elderly and sick were arrested: 8 of these were taken to Pospieszki and the rest freed. On July 26 the Jewish police handed over the Pospieszki prisoners to the German security police and their Lithuanian assistants who took them directly to Ponary and executed them. After this event, Gens spoke to the brigadiers (Jewish leaders of working groups) where he tried to explain the action and justify himself. He told them that he refused to hand over children but was forced to submit regarding the elderly and the sick.

Despite the murders mentioned, limited in scope, the Jews considered the period as being stable and calm compared to the endless shocks they knew in the first half year of the invasion. The 20,000 Jews still remaining in the city hoped they could continue their existence and the leadership concentrated on organizing the internal life of the Ghetto. In the period of ‘relative calm’ new forms of Ghetto living came into being, and changes took place in the organization of the Judenrat and the Jewish police.

The new re-organization after the great Aktzias was followed by internal strife between the Judenrat, the Jewish Police and remaining political public figures. Alongside the five members of the Judenrat (Antol Frid, Chairman, Grisza Jaszunski, virtually considered his deputy, Shabtai Milkonowicki, Yoel Fiszman and G. Guchman), a council of heads of departments existed. At the beginning of 1942 the Judenrat extended its activities and added to the administration and existing departments (food, health, housing, work) four new departments social services, education, culture and finance.

|

|

| The theater play “Shlomo Molcho” in the Vilna Ghetto, June 1943 Source: Yad Vashem photo archives |