|

for the city council election

|

|

[Page 239]

by M. Piltzmacher

Translated from Hebrew by Theodore Steinberg

Social movements were a consequence of the time, the circumstances, and the conditions in which people lived. And yet, the social movements were the forerunners, the standard bearers for new developments that the community needed, that the community craved, for which it fought, and especially the means by which it fought. They mirror the peculiarities of the time, the way in which people lived.

The first half of the century is rich in events, in social and political changes in relationships and consequently in gradual changes in the whole way of life.

When we take a look at our city of Ostrowiec, its Jewish way of life, its battle in the last fifty years: until its fall, until the destruction of the Jewish settlement by the Nazi bandits, we see before us a progressive Jewish social development that fascinates us with its rapidity.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century Jewish Ostrowiec was thoroughly religious at all levels of the people. Of course, there were always classes: the upper class of the aristocratic rich, the Chasidim, the learned, who looked with scorn from above on the “simple crowd.” But the “crowd” showed little rebellion and understood its miserable existence as “God's punishment,” for which people had to beg “forgiveness,” but they dared not rebel…

The poor, or the “commoners,” which consisted of a small number of manual laborers, workmen, had for their relaxation, so that they could feel at home among their equals, formed “fellowships,” minyanim for prayers. From those they derived their spiritual pleasures, their devotional satisfaction. For other things that really had no time. Their labor left them time only for their prayers, for a “bor'chu” and a “kedushah,” for a couple of quick bites, and then back into harness. The worker, no matter how long the day had been, had to set aside some hours at night to work in order to still the hunger of his household. When we take a look back to that time, hardly fifty years ago, a shudder seizes us.

|

|

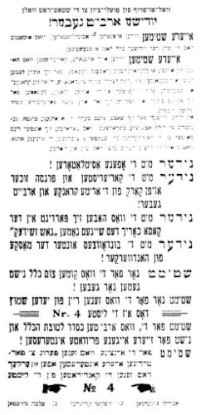

| Voting call from the Po'alei Tzion for the city council election |

|

JEWISH EMPLOYERS YOUR VOICES will prevent assimilation which has long enmeshed the Jewish community everywhere

VOTE for those who work for the common good and not for their own private interests!

|

[Page 240]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the revolutionary movement in czarist Russia against the autocratic rule of the czar over the huge empire joined with the movement for Polish independence–and this also reached Ostrowiec..

Then the socialist movement hit the Yiddish streets, under the influence of the movement for Polish independence and under the double lack of rights of Jews as Jews and as socialists.

With the arrival of the socialist movement on the Jewish street, there simultaneously began enlightened cultural activities, and there were efforts to eliminate illiteracy in the working masses.

This movement had to put up with immense difficulties. First of all, for the traditional-conservative factions in the Jewish world, this appeared to be a “desecration of the sacred,” God help us…

And when the nascent, primitive workers movement at that time undertook strikes in order to better the situation of the journeymen, who were paid by the hour and never knew definite working hours, and in many cases these journeymen worked for their boss for meals and lodging–one can easily understand what displeasure these “pushy socialists” brought to their bosses (who were basically working men).

Even more severe was the displeasure among the clerics. There then began a wave of provocations, denunciations, and terror, that

|

||

| Election propaganda for the city council election in 1927 | ||

|

Do you want your economic and cultural rights to be properly defended in the city council? |

|

||

| Election propaganda for the city council election in 1927 | ||

|

For the Jewish National Bloc In Ostrowiec Jews, Voters! The elections for the local city council will take place on Sunday, May 12. |

[Page 241]

was protected by the czarist Okhrana. Masses of workers were confined to prisons and sent to Siberia. Workers organizations, which were illegal, responded with terror. From time to time, the czarist functionaries who had served the czarist Okhrana and who had done terrible things to the revolutionary and local provacateurs, fell as victims.

This mutual terror lasted until the war in the Balkans, and it ended finally in 1915 when a patrol from the Polish Legion shot, in a spectacular fashion, the greatest informer of that revolutionary time, Avram'le Racimora.

After carrying out this revenge murder, the patrol withdrew, and Ostrowiec remained on the track of “no man's land,” between the Russian and Austrian armies. There was not a single Jew in the city then, I think, who did not consider this a deserved punishment…

At the time of the First World War, when all of Poland was occupied by the German and Austrian armies, when the people were forced to live under the regime of the Austrian occupation forces, there was enough time and employment–not really. In their hopes for the near future, after the war, new ideas started to hatch among the young people, new aspirations. It seemed like a new dawn when a new day was beginning.

The first thing that was legally possible was cultural work, even though that did not lack oversight by the occupation forces.

At the end of the winter in 1916, a group of upper-class young people, students, office workers from the biggest Jewish undertakings, some former

|

||

| Party fragmentation among the Jews of Ostrowiec, as in all of Poland, for the city council election |

||

|

JEWS OF OSTROWIEC! VOTE IN THE ELECTIONS! On Sunday, May 12, consider to whom you trust your livelihood for 4 whole years, so we ask the following:

1. Until now, who has defended the Jewish city interests?

|

|

||

| Party fragmentation among the Jews of Ostrowiec, as in all of Poland, for the city council election |

||

Remember, this is the last hour in which you must decide the fate of the city economy. There is no more time for politics, but everyone, men and women, should go and vote for the non-aligned list.

whose candidates will keep watch over Jewish interests. Leading these candidates is Leyzerr Bergelman, etc.

|

[Page 242]

fighters from “the fifth year” began to consider doing cultural work.

The upper-class young people were attracted to Zionism, which at that time in Poland had become an intense, separate movement that radiated national hope and romanticism. This really tempted the young people.

There were no powerful tensions among the various schools of thought in the young people. Ideologies had not yet crystallized. Rather, everyone was united by the desire to do cultural activities.

The first of these new cultural workers were Noson Ehrlech's older son, Leyzer and Yechiel Levi (Shmuel Levin's sons), Simcha Mintzberg, Leyzer Mintzberg, Avraham Malech, Velvel Eisenberg (from Drildsz, Reuben Shpielman's son-in-law), Edelman (from Apt, who had a shoe workshop on Koscielna Street), Yechezkel Zeigermacher's older son, and others whose names are hard to remember. These were all intelligent people and the most important workers at the very beginning. Later, with the growth of social awareness, there were many new workers.

The Library–The First Cultural Institution

The first important institution that was created was the Jewish library. And in order to make that possible, a drama circle was created under the leadership of Velvel Eisenberg. The first performance consisted of sketches, one-act plays, among them Sholem Aleichem's “A Piece of Advice” and “It's a Lie.” Later on they performed “The Yeshiva Bochur,” which was done with great elan and was very successful.

The library was organized by the pond, in a fine location. This was the new home for cultural young people in Ostrowiec.

Formally and officially this “Jewish Library” was without parties or class differences. But in fact, the city young people dominated the institution and turned into a base of Zionist activities.

This situation lasted until the fall of 1917. At that time there was in Ostrowiec a youth revolutionary movement that was both illegal and conspiratorial. Their revolutionary work consisted of distributing propaganda materials about socialism and against the Austrian occupation. At the same time, they undertook to influence the “Jewish Library” to take a position in favor of the simple working people and to oppose upper-class influences.

Under the growing revolutionary wave against war and foreign occupation, against the hunger

|

The election for the Ostrowiec city council will be on Sunday, May 12.

|

[Page 243]

that the war had caused, stood the consciousness of the young worker group, whose influence rapidly increased.

With the collapse of the Austrian Empire, the library was a dominating factor for the Jewish working class. The cultural bond of the till then united Jewish cultural movement was divided and was defined by a variety of ideologies.

The Distribution into Parties

The Zionist camp itself was divided into: General Zionists, Mizrachis, and “Shomrim,” which were mainly under the leadership of the aforementioned people.

The Jewish worker camp at that time split into two party-groups: a Zionist Workers board and a Bundist, which, as time passed, fought more and more, and both–each in its own way–fought with the bourgeois Zionists. And never mind that there was no “leftist” Po'alei Tzion, the Ostrowiec Po'alei Tzion sharply distinguished itself from their bourgeois-Zionist ideological partners.

The Po'alei Tzion consisted of young workers who had revolutionary fervor, and the “Bund” consisted of former revolutionaries from “the Fifth Year” who were like an inactive volcano. They were more moderate in their thought and played the role of “the intelligent” and “old revolutionaries.”

The first leaders from the Po'alei Tzion movement in the city were: Itzik Berger, a leader with a high level of revolutionary consciousness and social responsibility. This young man, from the lower class, was the heart and soul of the revived worker movement in Ostrowiec. Thanks to his tireless efforts in all aspects of party, professional, and cultural activities, he suffered at age 20 from tuberculosis. In mid-1920 he went to his brother in America, where he died a year later.

His nearest and closest co-worker from the time of the German occupation until leaving Poland were Hersh Kudlowicz (today–a teacher in the Worker's Circle School in Cleveland) and the writer of these lines. With the growth and strengthening of the Po'alei Tzion movement, more intelligent leaders from the Chasidic middle class arrived, such as Feivel Shteynbok (who died in Brazil), Meir Blankman, and others. Teachers and students from high schools also came, such as Kestenberg, Hersh Zamietshkowski, Yakov Kofer, Sonia Kantor, Moyshe Weiss Felger, Yechezkel Rutman, Shlifka and the younger Zeliger.

When the Po'alei Tzion movement was prominent in Ostrowiec and its neighborhood, other participants were the well-known medic (unlicensed), a revolutionary from “the Fifth Year,” Avramtshe Beinerman and then his brother-in-law Nachman Alman, who came from Tarla. Both were killed by the Nazis.

The “Bund” was led by Avraham Shertzman. His wife, Roza Teyblum (neither of them from Ostrowiec), Itsche Zinger (“Itsche Shabtai Meir's”), Velvel Fotzontik, Yitzchak Vogshol, and Itzik Grobber (who died in Toronto, Canada).

The Po'alei Tzion had their club, the “Workers House,” a workers' kitchen, a library. They dominated the professional worker movement in the Jewish world by ninety percent. They led with folk school, evening courses, and popular courses of learning for workers. For the summer months–a camp for children 4 to 12 years old and a very fine drama club that was led by Birkenwald and that performed the most recent literary pieces from that time, under the influence of the “Vilna Troupe.”

Later on the “Bund” also created a theater group under the direction of Itzik Grobber, who put on good theatrical performances.

Religious Parties

When we try to delineate Jewish parties, the Mizrachi Party (1918) stands out. It was led by Reuven Mandelbaum, Moyshe Lederman (Duvid'l Garber's son), a very talented and intelligent person, a councilman and city councilman

[Page 244]

and member of the community council in the Jewish community, Shmuel Vestel, Leibush Halshtok (Ettele Chanah Ever's son-in-law), Shia Kuperman, and–from the younger folk–Asher Birnboym (now in Brazil).

There was also the “Agudas Shlomi Emunei Yisroel” under the leadership of Shaul Kestenberg, Pinia Rosenman, and Alter Morra.

The “Mizrachi,” like the “Agudas Yisroel,” created a modern school for children, where the teachers thought that they were in competition for their “profession”, and they tried to fashion a professional organization to defend their interests. They even tried to go for help to the “Central Office of the Professional Workers' Union,” which took no notice for the following reasons: first, because the teachers were independent, not working for a specified boss; second, because the professional workers' movement did not consider it proper to defend the old or the new “modernized” religious study.

|

|

by Moshe Rosenberg

Translated from Hebrew by Pamela Russ

[ ] translator's remarks

It is still difficult now to make peace with the idea that Jewish Ostrowiec, with its yeshivos [religious schools], Talmud Torahs, and Zionist youth organizations, that buzzed with such pulsing life, went down and no longer exists. The memories swim past, one after another.

I remember the first gathering of the Zionist youth. The meeting took place in a location of the right-wing Poalei Tziyon. At that meeting, the active Zionist Dr. Shibber came out. In his lecture, he explained the goals of “Hechalutz,” and called for the self-realization of the goals of Zionism. He underlined that the only one who could join “Hechalutz” is someone who was prepared to change his life goal and immigrate to Israel in order to build our own Jewish country.

Soon after ending his richly filled lecture about 50 friends registered, and the Ostrowiec “Hechalutz” was established. The youth, who until now had a comfortable lifestyle, were thirsty for activity and tasks, and yearned to become productive and find physical work.

In fact, there were very few opportunities in Ostrowiec to get to a working position. The large steel factory “Zaklady Ostroweicka” [“the Ostrowiec steel mill”] was locked to the Jewish youth. The Jewish youth was only able to profit from the factory by hearing the signals at specific hours and adjust their clocks to that. Wanting to actualize their ideals, the first “chalutzim” who registered had to go out into the “Hachshara” places that were created in other cities in Poland.

But the older chalutzim did not agree to allow their children to leave home and go to a strange place. It was difficult to explain the meaning of this to them.

I remember a few incidents that happened because children left their home. The blond Zalman Joiczarzh went to the police with a report that they robbed him of his daughter Bashe. The secret agent Wikerek then came to the location of the “Hechalutz” to find out where Bashe was. I remember a second incident that is almost unbelievable. The shochet [ritual slaughterer] of the town Szenne, and his wife, came on Friday night to the ”Hechalutz” location out of breath from their long walk. The shochet took out his knife, placed it on the table, and cried out: “Slaughter us, because we have nothing to live for any longer, now that you stole our daughter Bashe from us!” Bashe had joined the Ostrowiec ”Hechalutz” because there was no such organization in Szenne. The “Hechalutz” had sent her away to a “Hachshara” and after that she immigrated to Israel, and after some time, she brought over her parents. With the knife that he had asked them to slaughter him, today he is slaughtering fowl in the Tel Aviv area. Thanks to the “lost” daughter, the parents remained alive.

I remember all kids of cultural and political projects that the group of the Ostrowiec “Hechalutz” undertook. We brought over all kinds of performers for outings, such as Jacques Levi, and Menachem Kipnis and his wife Zeligfeld. We carried out a very bold project that had many expenses:

|

[Page 246]

|

|

| Kibbutz “Geulah” |

We invited the chairman of the Jewish “Kala” [club], Yitzchok Gruenbaum, of the Sejm [Polish government] to deliver a lecture. In order to carry out the project, we borrowed money from a lot of people. A day before the gathering, we suddenly received a telegram that Gruenbaum had to delay his coming to our town, because he had to attend a conference with a Polish minister. The announcement unsettled us very much because this also forced us to close the location of our organization. We went into debt, which we were not able to pay back.

We then sent a special representative to Warsaw, friend Yisroel Hercyk [Yisrael Libai in Israel], so that he could come to an agreement with Gruenbaum. He found the famous leader still asleep. Gruenbaum explained to him that the conference would stretch until three o'clock and then after that he would be ready to go. Not having any other means of travel, he took a special taxi and rode with the lecturer on a snowy day. He telephoned us that Gruenbaum would come to us that evening. We prepared a festive welcome. The “Hanoar Hatzioni” [“Young Zionist”], and other delegates, went into the Kunów forest to await the esteemed guest. Because of the frosty weather, one flat tire after another happened. We waited in the forest until 10 o'clock, and the taxi had not yet arrived. Meanwhile, the crowd that was sitting in the hall had become impatient and demanded back their money from the tickets. The lecture began at 11 o'clock at night. The hall became filled, and Gruenbaum spoke about the theme of: “the political situation in the country.” After the speech, a banquet was organized and it went until early hours. After covering all the costs, more than 200 zlotys were left in our cashbox.

by A. Halevi

Translated by Sara Mages

The Society for Gemilut Hasadim

At the end of the first decade of the current century, the youth held a meeting in which it was decided to establish a Society for Gemilut Hasadim[1]. A committee was elected in the composition of: Mendel Blankman, Issachar Fisch, Gutman from Stodolna Street, Eliezer Mintzberg (Shraga's brother) and me. We received the first amount of money for the loans from grandfather Pinchi Mintzberg, Hirschel Fisch and my father. At the beginning of the summer of 1914, the society's capital reached 100 rubles. From time to time our parents gave us loans for the expansion of the operation. The amount of loans we distributed to the needy reached up to 6 rubles per person, and in special cases up to 10 rubles. The loans were given without interest, but we collected one percentage from the borrower to cover the expenses and to increase the capital.

One case, which started with sadness and ended well, was engraved in my memory. Before the holiday of Passover of 1914 we gave a carter, the neighbor of Issachar Fisch and Henelh Roenman, a loan of 6 rubles and received earrings from him as collateral. I always kept the cash box and the collaterals, and when we checked the accounts we discovered that the earrings were gone. We were astounded and didn't know what to do. According to the advice of Mendel Blankman, who was the oldest among us, we turned to my father for help. My father ruled that the treasurer should give 30 rubles, and the society would add 20-30 rubles as compensation to the borrower for the loss of the collateral. Blankman and I were assigned to approach the carter to negotiate

[Page 247]

with him. We were happy when we learned from him that the collateral was not lost, but was returned to him on the eve of the holiday to allow his wife to go to the synagogue on the holiday, because without earrings in the ears it was impossible for a woman to be seen in the synagogue. The society won 30 rubles because my father refused to take back the money he gave me, because charity money is not returned.

The activity for the refugees

In the summer of 1915, with the defeat of the Russian army near Wisła, many Jewish refugees, who were deported by the Russian army, arrived in our city from Ożarów, Lipsko, Ilza and Raków. At first, the refugees were housed in Batei HaMidrash next to the Great Synagogue and in the Hasidim's prayer houses. We worked day and night to provide them with food. After a few months we realized that it is not enough to give charity to the refugees, we have to give them constructive help. In the month of Kislev 5678 [1917], my brother Yehiel, Fruchtgarten and I, started to work on a plan for constructive help, such as teaching a profession, providing work, etc. I was assigned to speak to the city's residents and explain to them the need for constructive action, but I failed and all our efforts were in vain. Then the three of us decided to leave the committee for the refugees.

The library

We left the committee, but it was difficult for us to relax, we could not sit idly by and we were thirsty for action. We had 100 rubles, the capital of the Society for Gemilut Hasadim, , an amount that can be used as a basis for buying books for a library. We contacted Shmuel and Ezra Bomshtein and submitted a request to the Austrian military government to grant us a license to establish a library. Sometime later we received the license.

|

|

| Hashomer Hatzair |

|

|

| The “Gordonia” branch |

The library had to be at the disposal of all the Jewish youth in the city, regardless to their party affiliation. I think it was one of the few institutions in our city that were shared by all the parties. Under the library's sign we carried out Zionist activity and people of the Bund[2] - socialist activity.

The basis for the library came from the money of the Society for Gemilut Hasadim and the books we collected. However, right at the beginning an incident happened to me that could have caused the explosion of the institution. As the library's secretary I had to order the books, and I ordered 90% books in Hebrew. The matter raised the anger of the Yiddish speakers. A meeting of readers, members of the institution, was called, and I remember that in response to attacks on me I answered: who is reading books in Yiddish? Then, it was decided that the orders will be carried out by all the members of the committee.

The library existed from the end of 1915 to the beginning of 1919. A sad affair from the history of the library remained in my memory to this day, and it is - the takeover of the library by the members of the Bund. One bright morning, two members of the Bund appeared at my place and asked for the library's key to hold a workers' meeting. I gave them the key, and as usual in such cases, they had to return it to me at four o'clock so that I could exchange books for readers. The appointed hour has passed and I did not receive the key. I went to the library (it was at the Shitrsky's house at that time) and found the door closed. I knocked on the door and there was no answer. Sometime later, I received a reply: “The library is ours.” Those days were the days of lack of government in the city, only the Council of Farmers, headed by Pole named Punczak, managed the affairs. We approached him with a complaint and asked for the settlement of the dispute. After many meetings and debates, it was decided that the hall and the Hebrew library would belong to the Zionists, and the books in Yiddish to the Bund. This matter tainted the relations between the Zionists and the Bund to such an extent that my friends, Schwartzman and Idelman, who were members of the Bund, no longer spoke to me.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 248]

by Moshe Blajberg

Translated from Hebrew by Yechezkel Anis

[ ] translator's remarks

The year was 1927. We were a group of 13–15-year-old youths, graduates of the Mizrachi school, suffused with a Zionist awareness imbued within us by our teachers. Our longing for the Land of Israel found expression in the Hebrew language that we spoke among ourselves and in the Hebrew books that we devoured, everything from poetry to prose.

Meanwhile, there was a great crisis in the Land as the yeridah [dropping out] of new immigrants was increasing from day to day. The Grabski Aliyah[2] had failed, with some of our own townspeople among the returnees. The better-off merchants were bitter and spoke ill of the Land, while the younger idealistic ones returned despondent and withdrawn. Their conscience bothered them over their inability to weather the crisis.

They would occasionally visit the small meeting hall of the National Guard [HaShomer HaLeumi], soon to be called the Zionist Youth [HaNoar HaTzioni], and teach us some of the songs that came out of their ordeal. It was amid this atmosphere that the Zionist Youth became a bustling center of yearning for Aliyah to the Land.

Our ideological teachers and educators

It is only proper that I mention some teachers and a few others who left their imprint upon us and indirectly led to our organizing ourselves into a dynamic group of 200 Zionist youths who wielded a large influence over the town's other young people.

I am reminded of our teacher, Alter Yehudah Erlich z”l, who gathered around himself a small circle of students whom he would take out at dawn to the Kunow forest. There he would recite before us the poems of Bialik and Tschernichovsky. When he made Aliyah – we were then 10- or 11-year-olds – he left behind a great void that increased our longing for him and for the Land. We followed the occasional pieces that he would contribute to various Hebrew literary publications and with pride would brag that our teacher was a recognized, practicing writer.

I should mention as well another teacher, M.Y. Peker, whose fiery words and poems laid the foundation for the formation within our school of the Chaver group, which eventually became the National Guard. He even provided each of us with a hand-written membership card.

Another distinguished teacher was Genia Levy z”l who, in spite of the ideological differences among us, instilled in us the desire for a life grounded in justice and self-supporting labor.

The precious Yid, Reb Yehoshua Kuperman z”l, a Mizrachi man whose rendering of Kol Nidrei on Yom Kippur night would leave us all trembling, had no small influence on our future paths as well. We used to swallow up the conversation between Minchah and Maariv among the Mizrachi shul goers, when Reb Yehudah would pronounce with his dark, burning eyes: “Do not despair. Years ago, many Jews who emigrated to America came back as well, but those who remained – today they are Rockefellers!” His words were prophetic, for the few of our townspeople who managed to stick it out in the Land eventually struck roots and if they persisted, even acquired considerable assets.

Engraved in my memory is a wonderful picture of Simchat Torah hakafot at the Linas Tzedek shul. Leading the sixth hakafah I see Avramele Malach z”l proudly marching with a Torah scroll in one hand and a Simchat Torah flag produced by the Jewish National Fund in the other. He supported us in every Zionist activity that we conducted in the town. An opposing memory involves a certain Ostrovtzer named Meir'l Chazans who scribed a pathetic pamphlet in ridiculous language entitled “The New Tower of Babel.” In it he unleashed a tirade against Herzl's State of the Jews. How bizarre it sounds when I read it today.

The first meeting hall we used for congregating and organizing was on Malinska street – the hall of the Zionist Organization, who kindly availed their facilities to us. Its leaders began taking an interest in us, particularly one of its more active members, Leibl Klajner z”l, who became the head of our group. In one of the rooms there we discovered a veritable treasure – the ten-year-old library of the Young Guard [HaShomer HaTzair, a Socialist-Zionist youth movement], together with scouting gear and camping equipment. On every pamphlet was inscribed the name M.M. Kuperman, a name that was to become legendary. The son of Yehoshua Kuperman, who headed the Young Guard, M.M. Kuperman made Aliyah in the 1920s, dug and paved roads, but then became disillusioned and switched sides to become a leader of

[Page 249]

the anti-Zionist Palestinian Communist Party [PKP].

I recall the day that the Yiddish newspaper Haynt [Today] was nowhere to be found in our town. It was during the 1929 Arab riots when dozens of Jews were massacred. The reason for the paper's sudden disappearance from our town was an article reporting that the PKP had signed a secret memorandum of understanding with the riots' leader, the Mufti of Jerusalem. Among the signatories was our townsman, M.M. Kuperman. The paper was hidden by all so that his father would not have to see the report and suffer distress.

M.M. Kuperman's image fascinated us and so when his wife visited Ostrovtze after they were expelled from Palestine to the Soviet Union [where they met their end as Trotskyites], we invited her to speak to us about her husband and their experiences in the Land. She preferred to remain silent, but did join us in singing the Zionist songs of the time.

Our tenure at the hall of the Zionist Organization did not last long: a fire that broke out on one Shabbat devoured the building and everything in it, including our precious treasure, the library and camping gear. Our group was left without shelter, and so we would congregate on the ruins of the hall, with the sound of our singing carried into the distance. Many curious youths ended up joining us and our numbers steadily increased.

All sectors of the community were represented among us: the wealthy, public school children, even the poorest of the poor whose hard-working parents were very far from anything Zionist.

Our group conquers the Jewish street

I can recall an encounter I had with a Jew named Shmali Baruch Leizers, a Bundist [Yiddish-Socialist]. He was a porter who, perched on a curb in the marketplace, would devour the Bund newspaper – the Volks-Zeitung [People's Times] – from beginning to end. People used to say that after the Shabbat morning prayers he would walk to the railway station, a distance from town, in order to bring back the Volks-Zeitung, the only Yiddish paper to appear on Shabbat. At the time, the Bund had already disappeared from our town. When its national leader, Beinish Michalewicz, died, Shmali dropped everything and traveled to Warsaw so as to attend his funeral.

This same Shmali approached me once and said, “Granted I'm a sworn opponent of Zionism, a non-believer in the Land of Israel, but I would greatly appreciate it if you would accept my son as one of your group. I see you as the only youth group in town that knows how to attract the young and make them into menschen [decent human beings].” It goes without saying that we accepted him happily. There were many others like him.

By the way, that Shmali, in spite of his anti-Zionism, did not get any satisfaction from the 1929 Arab pogroms. Instead, he would tell us, “You have no business being in the Land of Israel. The imperialist English rule there and they're the ones who are responsible for everything going on. Take your revenge on them!” He suggested that we send dozens of youths to India in order to join the civil uprising there and increase the mayhem.

As our numbers grew from day to day, we found ourselves in need of our own meeting place. This turned out not to be so easy. No landlord was willing to rent out space to a youth group, given the noise and singing. After several runarounds, we ended up finding a place further out of town in a Gentile neighborhood, on the way to the Siennien forest, not far from the pig slaughterhouse. It was quite bold of us, but the new building afforded us ample space: a large courtyard for outdoor assemblies and several rooms for nighttime activities.

Each evening boys and girls would stream to our new warm headquarters [in winter, carrying coal and wood for the kindling stoves] and enjoy themselves until late at night singing and dancing, learning Hebrew and geography of the Land, attending various talks, and practicing their scouting skills.

All holidays and Jewish occasions were celebrated in the confines of our headquarters where we injected content and meaning into our lives. I remember a certain Pesach eve, with frost still on the ground, when a minyan of us made our way to the hall at dawn for pidyon bechor [redeeming the firstborn]. We kindled the stove and in the warmth it provided we spent that Pesach eve in accordance with Jewish custom. We imagined ourselves as characters in I.L. Peretz's story, If Not Higher, when the Tzaddik of Nemirov, masquerading as the peasant Vassil, brought firewood to a sick Jewish woman, lit her stove and stayed to recite selichot [penitential prayers] by its flame. In our case it was not the prayer of one man, but of many youths who had found new meaning in their lives.

On Shabbat the place hummed from early in the morning. In the afternoon we would read aloud from Hed-haken [“The Nest's Echo”], a pamphlet that we produced each week. It was edited by our leaders with the active participation of Avraham Rozenman, who already then exhibited talent both in writing and in speaking. I recall a communal gathering in the old shul at the time of the 1929 Arab pogroms. For the first time, Avraham appeared in the name of the town's youth and delivered a fiery speech on the implication of those events. His call for massive Aliyah to the Land left a deep impression upon those assembled. After that, he would represent us at all kinds of communal gatherings.

[Page 250]

We would produce a special edition of Hed-haken for special occasions. For the 50th birthday of Yitzchak Gruenbaum [a Zionist leader and member of the Sejm] we produced an edition in his honor and were even able to present it to him. Standing at the edge of the forest leading to Kunow on a cold snowy day, our entire group with its officers waited until late at night for Gruenbaum to arrive in town for a lecture. He was delayed due to a stormy session of the Sejm where he delivered a forceful speech against the anti-Semitic government.

An assortment of emissaries from the Land, representing all movements and streams, would visit our group. We drank up their accounts of events in the Land and they found in us a source of support for their activities in town.

We participate in local elections

As an organized youth group, we developed various social activities in town. We participated in the Zionist Organization's choir. We established a drama group and arranged an annual dance party whose proceeds went to the Jewish National Fund, even though we were too young to actively take part. Soon the town's authorities began taking notice of us. Viewing us as nothing more than a scout group, they did not look kindly upon our political activities. They knew that we represented Yitzchak Gruenbaum's party in the Zionist Organization and tried numerous times to challenge the legality of our activity.

The height of their harassment came with the 1931 elections for the Polish Sejm. The ruling party at the time, headed by Poland's revered liberator, Jozef Pilsudski, reneged on its promise of equal rights for Jews and other national minorities in Poland. Yitzchak Gruenbaum, from the podium of the Sejm, demanded our rights as citizens equal in every regard. Every speech he delivered served to encourage the Jewish masses, regardless of party affiliation, in their struggle against the oppressive Polish government.

It was in this climate that the 1931 elections for the Sejm began to take place. Amongst the Jews, the leaders of the ultra-Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party, together with assorted other machers [lobbyists], called for supporting the list of the ruling party, which bore the number 1. The Zionist Organization, with Gruenbaum as its head, appeared as a separate list, but found itself suppressed in most of Poland's provincial towns. No one would dare conduct a campaign in the light of day, and at night every campaign placard was destroyed by bands of thugs working for the government's list.

It was then that we Zionist teenagers mobilized ourselves into action. We operated at night so that by the next morning the whole town would be plastered with giant campaign posters and the paths covered with the number 17, that of Gruenbaum's list. One night, we broke into the Agudat Yisrael headquarters and seized all their campaign material as well as a printing press.

The government's secret police began pursuing us. I can't forget how one night, after returning from a grueling round of posting campaign placards, we were accosted by those thugs who laid in ambush ready to tear us apart. We began to flee, with them in pursuit, until we reached the street which housed the old shul and beis-medresh. We took refuge there knowing that these toughs would never dare enter our house of worship. We emerged victorious from that election campaign. Over 1,000 votes were cast in our town for Gruenbaum's list.

The first olim from Ostrovtze

From merely singing and dancing to Zionist songs, we proceeded to the next stage: attending hachshara [preparatory camps] for settling the Land and then ultimately making Aliyah itself. It was hard leaving behind the bustling life we had enjoyed, but all our desires were directed exclusively to the Land. Thank God that we had the foresight to leave school and family behind and to make Aliyah – before the great scourge…

On the deck of the ship, I already decided to direct my first steps in the Land to those few of our townspeople who had not abandoned it.

[Page 251]

I wanted to see them and let them know that there was a next generation in the town that thought like them. Once arrived, I sought out these people whom I didn't even know, as I was only 8 or 10 years old when they made Aliyah.

I met with Yechiel Levi z”l from Kibbutz Ginegar and gave him regards from his nephew. Standing before me was a Jewish farmer, a cattleman by trade but also a distinguished educator. He very much enjoyed our meeting and let me know it as we walked the length and breadth of Kibbutz Ginegar, which lies along the edges of Balfour Forest. I mentioned to him the letter that he had sent to his pious father, so detached from the problems of the Land, but which his nephew had shared with us. In it he spoke of the drought that they were suffering and of the rat scourge that consumed every good inch of field – simple words etched in pencil on “simple paper, gray as ash” [as in the well-known song, Two Letters], but which for us served as a complete treatise regarding the conditions of the Land.

I went to Jerusalem and visited the home of Shraga Feivel Mincberg z”l. Such joy and embracing of two fellow townsmen who didn't even know each other! I remembered him from my childhood, from the times he attended the Linas Tzedek shul on Shabbat. But now I was meeting a different Shraga Feivel, a laborer at the Dead Sea Works in Sodom who returned to Jerusalem every Friday. He had become the spokesperson for the Dead Sea workers organization. Towards the end of his life, he became active among Tel Aviv's workers as well.

Last but not least, there was Eliezer Halevi of Kibbutz Geva, may he live a long life. The elder of the group, he was the leader of the Zionists in our town and a well-known accountant – who left it all behind to make Aliyah. On the day I came to visit him, he had just finished his shift baking bread. He took me on a horse-drawn wagon to harvest green corn for the cattle shed. He showed great interest in everything that was happening back in his home town. He was a man of progressive views – a dreamer and a visionary. He left an indelible impression upon me as I took my first steps in the Land.

Those of my peers from the Zionist Youth who succeeded in making Aliyah formed a community of sorts in the village of Kefar Saba that we called Kibbutz HaMefales [“The Leveling Kibbutz”]. For a time, a dozen of us dwelled there together, seeing the kibbutz as a natural extension of our former lives. With time, however, the group broke apart and each found his own path in life while remaining faithful to the purpose of his making Aliyah.

I find it only proper to mention a few of them, and thereby bring this chapter of the Zionist Youth to a close. I will mention the active members of our town's group who made it this far, finding their place in the constructive and productive Jewish settlement of our Land:

On the way to the South, along the coastal road in the direction of Kibbutz Negba, stands an abandoned army camp which, during the Second World War, was occupied by the Polish Anders Army from which many Polish Jews were allowed to desert.[3] Amongst them was Tzvi Landau z”l who settled for a time on Kibbutz Usha. Alongside this army camp stands a modest marker, upon which is written: “Here fell our comrade Shlomo Rubinsztajn, commander of Kvutzat Nitzanim, in battle with the Arabs as he defended members of the farm on their way to work.”

Shlomo Rubinsztajn was a member of our group's youngest contingent. The son of hard-working parents, he made Aliyah on the illegal immigrant ship Asimi and joined Kvutzat Nitzanim. Following in the footsteps of his predecessors from our group, he became a leading member of the kvutzah, managing its orchards. It was in those orchards that he and his comrades fell defending the kvutzah from Egyptian invaders who overran and occupied it for a short time. Its members [including my brother Yechiel] were taken captive after a fierce battle between a few dozen Jewish youths and hundreds of Egyptian soldiers, armed and equipped with tanks and artillery. After spending half a year in captivity, they returned to reestablish Nitzanim as a thriving agricultural settlement. There one may find a memorial to those who fell in its defense, including its local commander, our fellow townsman, Shlomo Rubinsztajn z”l. The memorial stands atop a hill overlooking the settlement as an eternal testament to those who fell in its defense.

Translator's Footnotes

by I. Birnzweig

Donated by Avi Borenstein

Like in every Jewish town in Poland, Ostrowiec was also home to various youth organizations and movements from all streams, yet the different branches of the Revisionist Movement particularly excelled in their public activity, such as the Brit HaTzohar [Union of Revisionist Zionists] and Brit HaHayal [Revisionist Zionist Association]. The lectures held every Saturday at Brit HaTzohar by Adv. Friedenthal, who is now in Israel and by the late teacher Rabinovich, May G–d Revenge his Blood, were renowned among the youth movements and many came to hear them.

Among the figures who stood out the most in these organizations activities, were the Chairman Yisrael Rosenberg, May G–d Revenge his Blood, Shmuel Zussman, who represented the movement before the municipality and the community's committee and Secretary Moshe Goldfinger, who is now in Israel.

The Jews of the town experienced an exceptional experience when Zeev Jabotinsky appeared in Ostrowiec. The film theater was too narrow to hold all the masses that came to hear the leader and the nearby streets were filled with Jews listening to the speech from speakers installed especially for the occasion. Mr. Friedenthal had the tremendous privilege of receiving the distinguished guest and opening the lecture. Y. Rozensweig had a big part in the success of this event, after investing numerous hours preparing it. The lecture was followed by a party with festive tables at the home of Mr. Heine, the richest man in town and father–in–law of the Rabbi from Gur, who offered him his spacious and luxurious apartment. We sat there with the great leader until the early hours of the morning, listening to his words without feeling time pass.

Brit HaTzohar was established in 1927 by a group of youngsters headed by Yaakov Orbach. It evolved into an active and strong body that took part in the town's cultural and political activities.

Two years later, Shmuel Grossman and Eli Mintsberg established the Beitar Movement, which quickly developed and included most of the town's youth within a short time, mainly thanks to teacher Rabinovich, who contributed valuable cultural contents to the movement's activity, many ran to the lectures and cultural balls that he hosted. Beitar also organized summer camps, defense sports training, trips and more. When members of Beitar walked the town streets wearing their uniforms, they were considered by all as the start of the Hebrew army.

After the Nazis began WWII in 1939, an underground Command Center was established by the honorable Messieurs P. Shar, Rabinovich, K. Waldman, S. Goldman, Bluma Grossman and Rachel Steinbrat. Brit HaHayal was organized thanks to Captain Yakir Goldberg (Har Zahav), who came especially from Warsaw for this purpose. He managed to gather a number of young Jews after their service in the Polish army and lectured to them about the purpose of Brit HaHayal. Adv. Tzisel agreed to assume the role of commander and together with the rest of the Command members – Yaakov Zeltser, Eli Levi and others – managed to infuse the acknowledgment that all military veterans should take advantage of their military experience to benefit their brothers, wherever they may be and should protect Jews and their property from Antisemitism. However, they considered getting to the Land of Israel as their main goal, whereas at the time it was closed to Jewish immigrants. Many of them came to the Land of Israel as part of the Aliya Bet [illegal immigration by Jews], which was organized by Mr. Zaitsik from the Center and took part in protecting the Jewish settlements from Arab thugs.

The Nazi evil put an end to this vibrant life and our precious youth was destroyed.

Let these lines serve as a memorial for all the members of the movement who did not live to see their idea victorious in free Israel. May their souls be bound in the bond of life.

Translated by Sara Mages

Ha-Tsfira[2]

Iyar 5677 [April 1917]:

On the intermediate days of Passover was a general meeting for the association “Hebrew Biblioteka.” From the report it appears that there are now 566 books in this library, of them 252 in Hebrew, 212 in Yiddish and the rest in Polish. The income for half a year was 1037 rubles, and the expense- 1006 rubles.

15 Tamuz 5677 [5 July 1917]:

Our city's Zionists turned to the committee of Linat Tzedek[3] society to allow them to paste Zionist signs at the concert of the cantor Sirota which was held here by the aforementioned society. The committee did not reply. But, in a private conversation that one of the Zionists of our city had with the secretary of Linat Tzedek society, A.S., the latter explained that it is impossible to paste Zionist signs because it is an impolite. He also added that Warsaw should not be made into Jerusalem and to bring too much Judaism into Poland. Finally, we learned that Mr. Y.P., chairman of the aforementioned society, ordered his secretary to reply to the Zionists only after the concert…

12 Marcheshvan 5678 [28 October 1917]:

Yosef Czesler participated as a delegate from Ostrowiec in the Third Zionist Conference in Poland which took place in Warsaw.

19 Tevet 5678 [3 January1918]:

In the last few days our city was visited by our delegate to the Zionist Conference, Yosef Czesler from Warsaw, who gave a report from the third conference and lectured on the topics: “The influence of Zionism and Hebrew literature,” and “The vocation of the youth at this time.” The last two lectures were at the municipal theater. The speeches made a great impression and a Zionist association was founded in our city.

4 Shevat 5678 [17 January1918]:

[Page 254]

On 14 Tevet [December 29], a public meeting was held in the library hall by the temporary committee of the Zionist association. Mr. H.S. Mintzberg was elected chairman. After those gathered rose to honor the memory of the great author, Mendele Mocher Sforim[4] z”l, Mr. Riba spoke about Eretz Yisrael, and with thunderous applause a suitable decision was made unanimously.

13 Iyar 5678 [25 April 1918]:

On Monday, the intermediate days of Passover, the founding meeting of Mizrachi took place in our city. Mr. Y.M. Rappaport, who was elected chairman, opened the meeting and called those gathered to work. The number of members is reaching eighty.

The gentlemen elected to the temporary committee: A.Y. Mintzberg, A, Alterman, M. Szajner, B. Tropper, Y. Eiger, A. Baumfeld, A. Halshtok, M. Herceg, D. Brandspiegel, L. Zuran, Y.L. Goldstein, M. Kuperman, and M. M. Niskier. The committee planted in the name of the association eleven trees in “Ostrowiec Garden” of Mizrachi that the association has just founded. The Mizrachi organization set as its goal to start a broad propaganda in favor of the Mizrachi idea. On the seventh day of Passover, Mr. Rappaport gave a lecture that made a great impression on all those gathered.

Shavon HaMizrachi[5]

In the Mizrachi conference, held in Warsaw on 28 Nisan 5679 (28 April 1919), Mr. Y.M. Rappaport participated as a delegate from Ostrowiec.

Mr. M. Katz participated on behalf of Mizrachi in the general conference of Mizrachi held in Opatów.

17 Tamuz 5679 [15 July 1919]:

HaRav Y. L. Grossbart of Staszów visited the cheder[6] “Or Torah” of Mizrachi in Ostrowiec and prepared a curriculum for it. This cheder has a good reputation in the whole city and the number of its students has increased. The Mizrachi association already has 178 members and it has almost no opponents in the city.

|

|

| HeHalutz HaDati |

24 Sivan 5680 [10 June 1920]:

When the happy news of San Remo came to our city, on that day all the inhabitants of our city stood in the streets in groups and only talked about it. On the Shabbat, most of the city's Jews went to the synagogue and recited Hallel. Our member, R. Mandelbaum, spoke on current affairs. A special celebration was held on Lag BaOmer. All the balconies were decorated with blue and white flags. In the afternoon, a procession of all the national parties was held, and thousands of people marched under the Mizrachi flags. A public meeting was held in front of the community building. Now we started to collect funds for Keren HaGeula [Redemption Fund].

23 Heshvan 5681 ([4 November 1920]:

A general meeting of our members was held on the intermediate days of Passover. The meeting was opened by the chairman Moshe Lederman. In short and enthusiastic words he called the members to work. From the report it appears that despite the hardships of recent times, a decent amount was collected for Keren HaGeula and Keren Kayemet LeYisrael [JNF]. The members expressed confidence in the outgoing committee whose members are: chairman -Moshe Lederman, his deputy - Shmuel Westel, secretary - Yehusua Kuperman, treasurer - S. Westel,. The committee members: B, Stein, Tzvi Kleiman, Moshe Katz, Yakov Monheit, M. Szajner, E. Blumenstock, L. Hertz, Asher Birenbaum, Yakov Weintraub and L. Halshtok called the members to devote themselves to work. The meeting closed with the singing of Hatikvah.

The committee immediately opened the Mizrachi cheder.

12 Tevet 5681 [23 December 1920]:

On 4 Kislev [15 November], HaRav Rozenblum visited our city and spoke at Linat Tzedek hall. On the second day he lectured in the synagogue before a large crowd. His passionate speeches left an indelible impression.

28 Second Adar 5681 (7 April 1921):

On Purim eve the Mizrachi cheder held a Hebrew party at the theater hall. It was attended by members, students of the cheder and evening classes' students. The hall was full to capacity.

The teacher, Mandelbaum, opened the party in Hebrew. The play Shalom Aleichem Yehudi was presented in three acts and the play David and Goliath in five acts. Songs were sung in an uplifting spirit, and to the sound of the singing of Hatikvah the gathered left the hall. The audience saw for the first time that the Hebrew language lives in our children mouth.

With the participation of the teachers, and the female student Egar, we published a one-time newspaper called Or Torah, as the name of the cheder. In general, our work is progressing.

[Page 255]

Last Saturday our member, Brandspiegel, gave before the members meeting a report from the previous conference. The members expressed total confidence in the central committee in general and the decisions of the conference in particular.

4 Iyar 5681 [12 May 1921]:

On Sunday, 25 Second Adar [4 April], we called the foundation meeting of Tze'irei HaMizrachi in our city which was held at the Mizrachi hall. The member Brandspiegel opened the meeting with a short speech full of enthusiasm, in which he explained to the assembled the fundamental principles of Tze'irei HaMizrachi and their roles in the near future. Decisions were made after heated debates and a temporary committee was chosen that included the members: Brandspiegel - chairman, Topol - secretary, and the members: Algazi, Kesenberg, Hertz, Y. Bliberg and A. Bliberg.

The talks and lectures on various topics, held under the management of the member Brandspiegel, work out well and with success. On the Sabbath, Rosh Chodesh Nisan [9 April], he gave a lecture on the subject, Tze'irei HaMizrachi and their development. Many members participated in the discussion after the lecture. In general, a large and tangible movement is seen in our city in favor of our lofty idea.

10 Sivan 5681 [16 June 1921]:

On Sunday, 30 Nisan (8 April), we called the members of Tze'irei HaMizrachi for a general meeting. In the attendance of close to sixty members, the member D. Brandspiegel opened with a lecture on the Mizrachi idea and explained the roles of Tze'irei HaMizrachi.

The member, Stanovic was appointed chairman of the meeting, and the member Katz blessed the meeting in the name of the Mizrachi committee. The chairman read the resolutions of the conference of Tze'irei HaMizrachi representatives. From the report of the committee's activities, given by the secretary Topol, it appears that next to our association there is a Hebrew library named Seferot [literature], whose number of books and readers is increasing. Every Saturday, there are conversations with the participation of many members. There were several parties in Hebrew in which many of our members excelled. We collected about ten thousands marka[7] for the benefit of Keren Kayemet LeYisrael, our delegates in Keren Hayesod [UIA] and in the Eretz Yisrael office fulfilled their duties. A month ago, several people from our city immigrated to Eretz Yisrael, We already received letters from them informing us that they celebrated Passover, together with other guests at the Mizrachi Hall in Jaffa, and in three days each of them earned eight pound sterling. More than sixty people signed up for a trip to our country, among them a respectable number of young people.

The member, D. Brandspiegel, lectured on the necessity of learning the written and oral Hebrew language, and at the same occasion many members signed up for evening classes. The member, A. Birenbaum, talked about the classes for artistic training. The members elected for the committee: D. Brandspiegel - chairman, A. Bliberg - secretary, Topol - treasurer, Blumenstock - delegate for Keren Kayemet LeYisrael, A. Birenbaum - our city's delegate for the HeHalutz fund, Stevanovic, Kesenberg, Y. Bliberg and Algazi.

The member, D. Brandspiegel, gave the closing speech that aroused the gathered for work and activity.

The meeting closed with the singing of Hatikvah and with spiritual uplifting.

1 Tamuz 5681 [7 July 1921]:

On the first and second day of the holiday of Shavuot we held public meetings in which the following members lectured: the chairman Mr. Lederman, the secretary L. Halshtok, the teacher Mandelbaum, B. Stein, Brandspiegel, Kuperman and M. Katz, on current affairs and the political situation of our country. After the speeches this decision was unanimously adopted:

“The meeting expresses its confidence, that victory will finally be on our side, and that the gates of Eretz Yisrael will open immediately. We are all ready to make an aliya to our country, to cultivate its desolate soil and build the ruins of our country in the spirit of our Torah.”

21 Menachem Av 5681 [25 August 1921]:

On 25 Tamuz [31 July] a mourning party in memory of our great leader, Dr. Herzl z”l, was held by Tze'irei HaMizrachi organization. On the stage hung a picture of Herzl and the Mizrachi flag flew next to it. After we sold a cow for the benefit of Herzl Forest, D. Brandspiegel opened the party in Hebrew and gave the permission to speak to the teacher Wolman, who lectured about “Herzl and his history.” A memorial service was held and the choir sang mourning songs. The members Mendlbaum, Halshtok and D. Brandspiegel also spoke. The students recited various readings and the choir sang songs of Zion. The meeting closed with the singing of Hatikvah.

2 Marcheshvan 5682 [3 November 1921]:

Tze'irei HaMizrachi movement is well known in our city. We participate in all fields of work. Thanks to our member Mr. Lederman, member of the city council, A decent number of members of Tze'irei HaMizrachi were added to the population census committee. On Saturday, 1 October, our members spoke at the synagogue about the census.

|

|

| HeHalutz HaMizrachi |

[Page 256]

On Rosh Hashanah, before the reading of the Torah, the member D. Brandspiegel lectured at the Mizrachi hall about HeHalutz HaMizrachi fund. Among others, he emphasized that we want to fulfill our ambitions - we must work for this fund that enables the immigration of the religious members to Eretz Yisrael. His words made an impression and at the same occasion decent sums were donated.

9 Adar 5682 (9 March 1922):

On Saturday night, 6 Shevat [4 February], there was a lecture in our hall on the subject: “Our role after the Third National Conference.” The members Biranbaum and Brandspiegel, our representatives in the conference, gave a report about its meetings. At the end of their speeches they roused the members to actual work.

We approached the opening of the reading room and, in general, it is necessary to recognize among our camp the desire to act in all areas.

1 Nisan 5682 [30 March 1922]:

Two weeks ago was the annual general meeting of Mizrachi members.

The chairman M. Lederman and D. Stein gave a detailed report of the committee's achievements in the past year. A new committee was elected to which the following members entered: M. Lederman -chairman, M. M. Nihoz - secretary, M. Sheiner - treasurer, Y. Kuperman, A. Zilberberg, S. Wastel and M. Langer.

The counselor, Mr. Zukerman, who visited our city, brought great benefit to the development of our association. He lectured on Shabbat Kodesh at the city's Beit HaMidrash and his words made a great impression on the city's Jews.

Our existing school is developing in a very desirable way. A fourth department will be open in the summer. On Purim we held a Hebrew ball by the school students in a rich program.

We are starting to collect the organization's dues from our members and hope that the collection will be successful.

|

|

| Ken Hashomer Hadati in Ostrowiec, 24 Iyar 5695 [27 May 1935] |

1 Nisan 5682 [30 March 1922]:

In Ostrowiec, the Shlomeim threatened that if a protest meeting will be held against the orthodox delegation in Jerusalem to Lord Northcliffe, riots and blows would break out. The City Rabbi, the genius and famous tzadik, intervened in this matter, and after a long conversation with the leaders of Mizrachi, a decision was made to draft a resolution that would also be signed by the Shlomeim. Such a decision has been made with the rabbi's consent, but, the Shlomeim did not want to sign it… Then, the police commissar announced that the Shlomeim came to him and informed him that Mizrachi and “thugs” will hold meetings that would reach to beatings. When Mizrachi leaders explained the matter to him, and showed him the approval of the community's authorities, he gave them the license to hold the meeting. At that time, the leaders of Agudat Yisrael came to him and informed him that Starosta[8] Bapet did not give a license for such a meeting last Saturday, and began to slander the community's authorities… The commissar asked the Starosta by phone, and the latter allowed them to hold the meeting. The leaders of the Agudat Yisrael saw that they were not successful in delivering incriminating information, and turned to the rabbi with new incriminating information, because during the meeting “they will talk about God and his Messiah…” The end of the matter was that the rabbi himself came to the synagogue on Saturday morning and read the wording of the decision by himself:

“Since they say, that irresponsible people spoke against Eretz Yisrael in the name of the ultra-Orthodox Jews, and since we also belong to the ultra-Orthodox, I inform that they told a lie. We all want Eretz Yisrael.”

But with that the matter did not end. The ultra-orthodox Jews held a protest meeting, and on Saturday night there were heated arguments between the members of Mizrachi and the Shlomeim at the rabbi's house. The rabbi announced that he does not belong to any party, nor did he allow anyone to bless the Shlomeim on his behalf…

13 Nisan 5682 [11 April 1922]:

The visit of the counselor, the member Elimelech Zukerman, in our city left a great impression. In a large public meeting in the Beit HaMidrash HaGadol, Mr. Zukerman spoke on Zionism and the people. His speech, which lasted about an hour and a half, received special attention from the audience. Our member, Mr. Y. Z. Wiener, lectured after him on the obligation of the people to Zionism.

Before the member Zukerman left our city, we held a committee meeting with his participation, and by virtue of its decision we are already arranging the collection of the organization tax from our members.

Dos Yidishe Folk [The Jewish People]

5 Elul 5677 [23 August 1917]:

The local Zionists joined to organize and establish a Zionist association, at which evening courses would be opened for Hebrew language, the Bible and Jewish history.

Translator's Footnotes

Tze'irei HaMizrachi was an organization of young members of Mizrachi founded in Poland in 1918. Return

Translated by Sara Mages

“Der Jude[1]”

Tuesday, Ki Tisa

[2] 5679 [1919]There are about 5000 Jewish families in our city and most observe Torah and tradition. A broad social-philanthropic activity is underway. However, so far nothing has been done to organize the poor Jews in an organizational framework so that foreign parties wouldn't speak on their behalf.

We have different parties, and each one tries to speak on behalf of all Jews. The orthodox stand at a distance, but all Torah and tradition observant Jews have the duty not to remain indifferent, but to take the initiative to organize the orthodox in the association Shelomei Emunei Yisrael[3], as is customary in all towns where such an association doesn't exist yet.

The notice as follows, on behalf of the city rabbi: With God's help, bless be He, I've heard that people slandered me for being against the association Shelomei Emunei Yisrael, I must reveal and announce that this is a complete lie. On the contrary, I reply to anyone who asks me that now it is a sacred duty to join the aforementioned association, because the association was founded for the God-fearing and the ultra-Orthodox, and I command everyone to join them - the writer for the sake of truth HaKadosh Meir Yechiel HaLevi of Ostrowiec.

4 Menachem Av 5679 [31 July 1919]

On Monday eve, the Rabbi of Ostrowiec entered to one of the cars of the train that traveled to Radom. With the rabbi also traveled the Rebbe of Wachock with his Hasidim. When the train moved from its place, two armed man ran to window of the car where the rabbi was, snatched the shtreimel[4] from his head, gave him a few blows, and ran away. The Hassidim, who were in the train, asked the official in charge of punching the tickets to delay the train and stop the rioters. But the train kept going. From Szydlowiec they called Skarzysko to ask them to arrest the rioters and to take the shtreimel from them. But no one answered.

|

|

| HaRav HaGaon the Admor of Ostrowiec accompanied by his entourage in the summer house in Otwock |

Translator's Footnotes

by Yehoshua Urbas

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

The news that the war had broken out spread like lightning through the streets of Ostrowiec and caused terrible turmoil. Life was suddenly paralyzed.

There was a stampede in the city. Parents ran to their children–children ran to their parents. People also ran to stores to stock up on food, fearing the hunger that was to come.

On the streets people began to dig protective trenches where they could take shelter in case of bombardment.

In the course of a few hours life, which had been so normal, was completely overturned. It could no longer be recognized…

Soon the first mobilization was carried out. Special couriers appeared in the streets and distributed among the inhabitants calls to appear for the army. Because there was no time to accomplish this by mail, special couriers were sent.

So a notification came to the home of the Falkman family for Yonatan, who was twenty-five years old.

There was no one at home except for the little children. The mother and sixteen-year-old Ezra, who helped support the family, were at work.

Yonatan came to eat his lunch. It was twelve o'clock, the time for his afternoon break. He took from his shoulders the yoke with the buckets and began reading the notification.

“Yes, it's calling for me!” he said, and his face, with its wide nose, gave a start and lost for a moment its natural ruddiness. He sank into thought…

Finally he began to eat his lunch, cutting a piece of bread, small, as usual, dipped in borscht.

Then he stood up and began to pack his bag, the same bag that two years earlier he had emptied after regular military service.

Into the bag he put a photograph–a photograph of his fiancée Malkah, some envelopes, writing paper, and shaving equipment. He also wanted to take with him a picture of his mother, and he deeply regretted that his mother had never been photographed. She never had because she was an observant and God-fearing woman.

While he was packing, sixteen-year-old Ezra arrived. He was terrified. The packing gave him a fright. It is known that the departure of his brother Yonatan for the army affected him terribly…

In such a family, where there was no father, there was among the children an especially deep relationship with each other and with their home.

After the packing was finished, Ezra said, “Come. I will go with you to the train, Yonatan…”. He said this in such a voice that he sounded like a breaking dish.

But they did not leave then. They waited for their mother.

But they could not wait long. The notification called for those who were mobilized to appear at the train station at precisely two o'clock.

Her children did not know where to look for her. She, their mother, was never found in a single place, because her work required her to be in different places.

Ezra ran to search for her among the neighbors but–without results.

Finally Yonatan embraced the children, said goodbye to his sisters–

[Page 272]

Yocheved, Reizel–and his brothers–Yerachmiel, Chaimke, Pinchas–held them close, then took up his bag.

The way to the train station was not long. Ostrowiec, after all, was not such a big city.

It was somewhat divided in two: one part of the city was the market, with its surrounding Jewish area. The other section began behind the hill, the long, broad avenue that led to the Christian quarters, to the park, to the factory, and to the train station. It was about two kilometers.

But on that day the two brothers looked at the road for a long time. The road was troubled…because no one knew where it would lead?…

On the road the two brothers were silent. Each thought about himself…

Yonatan, who was being mobilized, thought about the situation, about his mother and the children whom he was abandoning, who would be left hungry. As he was thinking, Yonatan saw himself at home, helping his family. Soon after the family had been left without their father, who had died an unnatural death, the whole burden of feeding the family had fallen on the shoulders of seventeen-year-old Yonatan. At home were the children with their helpless mother, who in this terrible situation did not know where to turn. Consequently, he, Yonatan, had not learned a trade, because he had to go to work immediately so he could earn money. He became a watercarrier. He bought a yoke and began with two buckets, huge buckets. At first the other water carriers really did not like him, because they feared the competition. But later they found him to be a good friend: --he had increased the price from five groschen to seven groschen for two buckets. At first, he did not like being a water carrier, but later he got used to it. He felt about his profession like most manual laborers that he was serving a purpose in order to earn money and to exist.

In the evening, when he returned home after a workday, he gave his mother the money he had earned. At the same time, she returned home with the little money she had earned. Both of them–she and Yonatan–left home early in the morning, he with his yoke and buckets and she with a can in her hand. He carried water that he drew from the well on the street, and she carried milk in her can. She got milk at the dairy and carried it to the homes. For each liter of milk that she sold, she made a profit of two groschen. She did this until ten o'clock. Then she went home and made something for the children to eat. Then she was off again, this time to another job, taking in laundry from one or another household.

And so things went on for several years.

Ezra, the younger brother, now accompanying his brother to the train station, also thought about home: he remembered the time when Yonatan went away for military service. For a year and a half, he was abroad. That was the hardest time, as he recalls…His mother, more than ever, talked to their father…she was immersed in her thoughts…They had to relinquish their home, which consisted of a room and a kitchen, and go to a smaller room that held only their beds. Moreover, their long table was not there. In no way did it fit…Nu, so the children began to do their lessons at the little table. The days passed painfully. Nights–hungrily. Many evenings ended with cries from the little ones, Chaimke and Yocheved, who did not understand, who could not understand, that sometimes one had to go to bed without an evening meal. So, when Yonatan returned home oh, then everything changed. Life was as it had been. Their mother was happier. So were the children. They also began to make a soup in the morning. “A frugal soup.” He, the big brother, went with the children to a

[Page 273]

bookstore. Once he borrowed from them a “necessary book” from neighbors…Their home was clean, warm, as it had been before. With Yonatan home, the house was heimlich and good. Now…Now they were taking him away again. For how long?

“How long do you think the war will last?

Yonatan did not answer.

Ezra, understanding Yonatan's thoughts, wanted to comfort him, to say something, but his tongue would not move.

Then, as they approached the train station, he said, “Don't worry, Yonatan. I will look after them…I will begin to work hard, harder than before, so that Mama and the children will not go hungry…”

Yonatan arranged his bag on his back, looked at his brother, thought directly about him. And it seemed that now, for the first time, he saw his character, that of his little brother. He wondered at his body–so thin…so small and emaciated.

Yonatan heard what he said, saw how the blood rushed to his face.

At the station, when he hugged his little brother, clutched him, he said, “I know that you will do it. You are already a man, not a child. You are no longer a child. It is not permitted…Now you have become a man. You will pay attention to our home…I have taken our father's place. Now you must take my place. And…when I return, perhaps you will be as tall as I am, and also a good earner…”

They said goodbye and kissed.

And Yonatan went to the train.

Many people were already standing by the train, a big crowd: aside from those being mobilized there were many others–fathers, mothers, men with suitcases in their hands, women, children, old people.

Women appeared with flowers in their hands for the called-up soldiers.

Peasant men and women–with warm bread–accompanied their sons with all their goods.

Alongside the train stood officers. At the station door–an orchestra played various military marches.

This was the first train of mobilized soldiers, all men who had been discharged–a train that had to go from Ostrowiec to the already engaged army that had begun the defense against Hitler and Germany.

Mothers were soaked with tears, their scarves fluttering in the wind.

“You should return. You should return!” yelled Ezra to Yonatan as he guided his steps to the train.

Suddenly, as he approached the train as Yonatan was already on the last step, with his right hand grasping the handle of the door, at that moment was heard the shrill whistle of the alarm siren, cutting through the air with a terrible sound that made everyone shudder. Everyone, without exception, began to run. Over their heads appeared German airplanes. They filled the sky. The noise of the airplanes mixed together. There was total confusion. After the first explosion, people ran wildly, sought somewhere for protection. It was a mob, a tumult. People fell over each other, then got up and ran.

The chaos increased when a cloud of smoke encased the whole platform after the first explosion.

After that explosion, Yonatan jumped from the train and landed on the stone platform, where Ezra grabbed his hand, and they ran away from the train.

After the second explosion, they separated, lost.

“Yonatan, Yonatan!” screamed Ezra.

Running into the crowd, he ran around seeking his brother.

The clatter of the wagons deafened him. He did not see the falling, the loud rolling of the train cars. His eyes were blinded by the thick clouds of smoke and dust that came from the bombs.

[Page 274]

“Yonatan, Yonatan,” he called, bent over and protecting his head with his hands.

But Yonatan did not hear.

Yonatan was already laid out on the earth.

His head, Yonatan's, covered with thickly grown, long black tufts of hair, lay with his face up, his mouth half open: blood seeped from his half-open mouth. His pack, his military pack that was on his back, between his shoulders, with its leather straps had cut deep into the flesh of his arm as he fell. He breathed heavily; his breath rattle. Near him lay a piece of a destroyed wagon.

When Ezra saw him, he ran to him and fell with his face on his body: “Yonatan!” He tried to rouse him, as one shakes someone who has fainted when trying to wake him…

Yonatan did not respond.

Ezra, despairing, hit his head against the stones.

Then he pulled himself together and tried to help his wounded brother, tried to ease his pack, to ease the strap on his arm. And in the confusion he called out for help.

But his cries mixed together with the other terrible cries of many people.

Tearing the young man away from the wounded was the first task when “first aid” appeared on the ruined platform. A horse-drawn ambulance from the “Red Cross”. came and began to remove the wounded.

The ambulance, after the wounded were loaded, began to move.

Ezra followed it.

The ambulance picked up speed.

Ezra did, too.

The ambulance disappeared from his sight.

Ezra continued to run in the same direction.

Out of breath, sweaty, breathing hard, with blood-flecked clothing–the blood of his brother Yonatan, whom he had embraced–young Ezra arrived at the hospital yard.

The wounded, who had been placed in the ambulance, were now on the floor, in the corridor, while places were prepared for them in the hospital rooms.

Ezra tore a path through the people who were arriving and began to seek his brother among the wounded.

“There he is!”

His cry, the sudden cry of a boy, a shocking, spasmodic cry, drew the attention of the hospital personnel: a nurse, a medic, and a doctor.

The nurse, a concerned young woman, took the boy by the hand.

“This is no place for you.”

She led him into the corridor.

But that did not help. Ezra could not help himself: however often he was led out, the boy always managed to appear near his wounded brother.

Finally, when the hospital personnel, with the help of the police, had cleared the courtyard of the desperate visitors, freeing up the way to the door, Ezra could not get through. But he could not go home…

He remained standing by the hospital window, listening closely to the voices of the wounded. With his eyes on the door, waiting, at every opportunity, to everyone who came out–the nurse, the medic, the doctor–he asked the same question about his brother Yonatan Falkman's condition…

“He is wounded…”

The nurse took pity on him and came out to him several times to give the latest report on his brother's status.

Finally, she grew tired and said, “Young man, go home. With your crying, you're not helping the wounded at all…”

This only increased his suffering.

Night fell, a very dark night. Tired, weak,

[Page 275]