|

|

55°49' 25°30'

Kamajai (Kamai in Yiddish) is located in the eastern part of Lithuania, about 13 kilometers south of the district administrative center Rakishok (Rokiskis), on the banks of the Seteksna River. Forests, fields and villages surrounded the town. Its beginnings go back to an estate with the same name mentioned in historical sources from the sixteenth century.

Until 1795 Kamai was included in the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom. At the time of the third division of Poland by the three superpowers of those times, Russia, Prussia and Austria, Lithuania was divided between Russia and Prussia. As with most of Lithuania, Kamai became a part of the Russian Empire, first in the Vilna province (Gubernia) and Vilkomir district and from 1843 in the Kovno Gubernia and Novo-Alexandrovsk district. In the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century Kamai was a county administrative center and this status extended to the period of Independent Lithuania (1918-1940), and then later in the Rakishok (Rokiskis) district.

The town held weekly markets and three annual fairs.

During World War 1, from 1915 to 1918, the town was under German military rule.

Jewish settlement before World War I

Jews began to settle in Kamai in the seventeenth century. In 1766 the town had 216 taxpayers. In 1847 there were 453 Jews in Kamai, and according to the all-Russian census of 1897, the population had risen to 1,105, of whom 944 were Jewish (85%).

The market place was in the center of the town, with four alleys branching out from it: the synagogue alley, the mill alley, the bridge alley and the Meshchansky alley that led to Panemunik (Panemunelis) where the railway station was located. Migrants to South Africa and America departed from this station. There was a tavern in the middle of the market.

At that time most Jews worked in trades. Some were shopkeepers, others engaged in the flax trade, in taverns and peddling. A few sold eggs, with a market extending to Riga. Jewish fishermen bought leases to fish in the lakes in the surrounding areas. A local Jew ran the post office, and a Jew owned the town pharmacy. There was no doctor, but a paramedic, Hayim Shalom, provided medical services. He was also able to prepare medications; this angered the town's pharmacist, Yoshe-Ber Garber, who informed authorities, and the paramedic was sent to jail. Garber later sold his pharmacy to a Lithuanian and emigrated to America.

Skilled workers in Kamai included three tailors, two glaziers, two shingle technicians, two blacksmiths and two shoemakers. People came to Rakishok to buy well-tailored suits. Only the barber was not Jewish. There were also musicians (Klei Zemer) who would travel to play at weddings.

In general the Jews were poor. Occasional fires exacerbated their poverty and only a few Jews remained prosperous.

The three annual fairs were major events in the life of the town. Because the majority of the population was Jewish, fairs were not organized on Sabbath days. This arrangement was supported by peasants from the region who wanted to trade with the Jews at the fairs. Many farmers, butchers, horse traders, rich and poor would come to the fairs. Jewish housewives made cakes and baked goods, and the income derived from these days enabled the Jews to earn a basic living.

Sometimes peasants caused disturbances in town, and the Jews feared pogroms. Christian hoodlums would get drunk and break windows in Jewish homes, and even assault Jews on the streets. Once a Jewish youngster challenged some hoodlums and inadvertently injured one of them. Panic broke out, and police from Rakishok arrived to investigate the case, but the shooter was not caught. On another occasion hoodlums from three neighboring villages arrived to instigate a pogrom against the Jews. The Jews called the Cossacks in from the nearby garrison to disperse the rioting crowd. On one occasion, Lithuanian leaders intervened in favor of the Jews, after receiving promises of support for their national and political activities.

Kamai suffered frequently from fires. The worst fire occurred in 1915 when almost the entire town burned down, and many Jewish families became homeless. Neighboring communities such as Rakishok sent aid to the victims. As a result of the fire most of the Jews left the town, and only ten families remained. After the war some of the former residents returned home.

Kamai Jews were divided between Hasidim and Mithnagdim, praying in different prayer houses. In addition, an old Beth Midrash accommodated worshipers during Yamim Noraim (the High Holy Days). For many years the building was left unfinished, without a roof and a floor.

From time to time there were interruptions in reading of the Torah in the prayer houses to collect money for heating from the worshippers. Another method for collecting money for the maintenance of the synagogue and the bathhouse was to take the men's Tallithoth on Shabbath in order to extract a pledge.

Before World War I a yeshivah was opened in town. The yeshivah was established by Rabbi Eliezer-Ze'ev Luft, the rabbi of the Mithnagdim, who also gave lessons, and Rabbi Yisrael-Zisl Dvoretz, who inherited the position of the town's rabbi after Rabbi Luft left. Rabbi Luft was a student of the Telz yeshivah and supporter of the Musar (Ethics) movement. More than fifty boys attended the yeshivah, which had “food days” – three meals a day at the home of a different wealthy family. The yeshivah became well known in the surrounding areas, and boys from the neighboring communities also joined it.

Zionism had its supporters in Kamai. There was one subscriber to the Hebrew periodical HaTsefirah. Rabbi Yisrael-Zisl Dvoretz was a delegate representing the Mizrahi party at one of the Zionist Congresses, and brought home a thermos flask, that caused a wondrous uproar in the town.

The 1905 revolution against the Czar was felt in Kamai. A clerical student, Jurgis Semeiskis (spelling uncertain), left his studies and organized a large meeting at the market square which had been decorated with red flags. The chief of the local police (Pristav) and three of his men were forced to remove their police hats and even to carry a red flag. A Cossack unit was rushed to Kamai to quash the riot. They looked for Semeiskis but he had disappeared, so they completely destroyed his house. With the establishment of Independent Lithuania, he returned to Kamai and became a headmaster of a school, but some time later he was assassinated for political reasons.

In 1915, when the German Russian front neared the town, most of the Jews left. Only ten Jewish families remained, and subsequently the German military sent them to perform forced labor on the railway line in Rakishok.

The rabbis who served in Kamai were:

Dov ben Avraham, in 1785

Bunim-Tsemakh Silver

Avraham Hirshovitz, from 1884

Eliyahu Gordon, from 1899, a learned man and a preacher, he wrote several books, later moved to Vilna. He was replaced by a young rabbi, a student of the Telz yeshivah, Eliezer-Ze'ev Luft (1871-?), the founder of the yeshivah in Kamai together with Rabbi Yisrael Zisl Dvorin, he arrived in Kamai in 1906, later emigrated to Eretz-Yisrael.

Meir Fain, emigrated to America.

Yehudah-Leib Siger, the last rabbi of the Kamai community, was murdered in the Shoah.

The Hasidic community had its own rabbi, Leib, the “Old One,” born in Ponevezh. They also had a Shohet, Avraham-Leib Atlas who was a learned man.

Hasidic controversies arose often in Kamai.

During the period of Independent Lithuania (1918-1940)

After the war the Jewish community of Kamai needed aid. In 1919 the YeKoPo organization in Vilna spent 2,500 Marks on community support. At the beginning of 1920 the sum was increased to 9,000 Marks, and at the end of that year to 12,000 Marks. All this money was spent on food.

According to the first census performed by the new Lithuanian government in 1923, 336 Jews (153 males, 183 females) lived in the town.

Following the passage of the Law of Autonomous Minorities by the Lithuanian government, the Minister for Jewish Affairs, Dr. Menachem (Max) Soloveitshik, ordered elections to community committees (Va'adei Kehilah) to be held in the summer of 1919. In Kamai a Va'ad with five members was elected. The committee worked in all fields of Jewish life until the end of 1925.

At that time the Kamai Jews made their living mainly in the small trades. The weekly market days on Wednesdays and the three annual fairs still provided a source of income.

According to the government survey of 1931, there were eleven shops, all belonging to Jews: two butcher shops, two textile shops, two restaurants, one haberdashery shop, one flax business, one grocery, one leather shop and one sewing workshop.

In 1937, ten Jewish skilled workers provided services in Kamai: four shoemakers, three butchers, two tailors and one baker.

In 1939, eighteen telephones were listed; three were in Jewish homes.

|

|

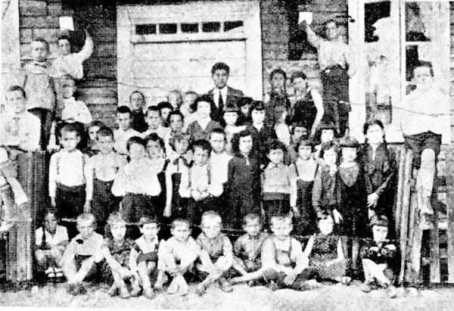

| The Hebrew school |

At the beginning of this period Jewish children continued to study at a Heder, but later a mixed Hebrew school from the Tarbuth chain was established with about 50 to 60 students in five grades. The teachers were Miss Jeruzalem from Shavl (Siauliai) and Ya'akov Harit from Dusiat (Dusetos) who subsequently became the headmaster. The school taught arithmetic, Hebrew, Jewish history, nature, Jewish prayers and customs, Lithuanian history, singing and gymnastics. The school also had a performing choir. A large number of graduates continued their studies at the Hebrew gymnasiums in Ponevezh (Panevezys) or Vilkomir (Ukmerge).

The traditional Heder remained open with about twenty boys.

The Zionist movement was active and among others things, established a large library with Hebrew and Yiddish books. The local Zionists bought Shekalim and took part in the elections to the Zionist congresses as shown:

| Congress No. |

Year | Total Shkalim |

Total Votes | Labor Party

|

Revisionists | General Zionists

|

Grosmanists | Mizrakhi | ||||||

| 16 | 1929 | 9 | 9 | 5 | — | 1 | — | — | — | 3 | ||||

| 17 | 1931 | 19 | 15 | 12 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 2 | ||||

| 18 | 1933 | — | 59 | — | 52 | 4 | — | — | 3 | |||||

| 19 | 1935 | — | 98 | — | 92 | — | 1 | 5 | — | |||||

The Hashomer Hatsair youth organization had an active branch in the town.

Among the personages born in Kamai were:

Professor Shemuel Atlas (1898-?), son of the Shohet of the Hasidic community Avraham-Leib Atlas, a graduate of the Slabodka and Ponevezh yeshivoth and the University of Berlin. He was also a lecturer of philosophy and Judaism in many institutes and universities, in Cambridge, Oxford, Cincinnati and New York; he published many books on philosophy including The Contemporary Relevance of the Philosophy of Maimonides (1964).Rabbi Yitshak Agulnik, a graduate of the local yeshivah, he served as rabbi in Posvol.

Aharon Agulnik, his brother, head of the famous yeshivah in Novogrudek.

Rabbi Yisrael-Nisan Kark (1867-1938) served for forty years as a dayan (religious judge) in Kovno and as the chairman of the Mizrahi party in Lithuania until his immigration to Eretz-Yisrael in 1927; he was a delegate to the twelfth Zionist congress. He died in Tel Aviv.

Shemuel Her (1887-1950), writer and teacher, in Eretz-Yisrael in 1927, he published many books in Yiddish and Hebrew including The History of Talmudic Literature (Tel Aviv, 1937). He died in Tel Aviv.

|

|

|||

| Professor Shemuel Atlas | Rabbi Yisrael Nisan Kark |

|

|

| Shemuel Her |

During World War II

In June 1940 Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union, becoming a Soviet Republic. Following new regulations, a number of shops belonging to Jews in Kamai were nationalized. All Zionist parties and youth organizations were disbanded. The Hebrew school was closed. Supply of goods decreased; as a result, prices soared. The middle class, mostly Jewish, bore most of the brunt, and the standard of living dropped gradually. At this time about 50 to 60 Jewish families still resided in the town.

The Germans entered Kamai on June 26, 1941, four days after the beginning of the war between Germany and the Soviet Union. Jews who owned transport tried to escape to Russia but most were stopped in Rakishok. There they suffered abuse and torture together with Rakishok Jews, and eventually were all murdered together with them.

Before the Germans entered Kamai, Lithuanian activists tried to take over the government institutions in town. The Soviet police resisted, and according to rumors, 15 Lithuanians were killed in the fight. This enraged the activists even more, and following the retreat of the Soviets, they instigated a pogrom against the Jews. They abused Jews badly and looted their property. Many of the Jews were beaten and tortured and a few were murdered before Germans were even seen in town.

With the Germans invasion, the situation of the Jews worsened. They were expelled from their homes and were told to gather at the Beth Midrash. There they were kept without food and water. By some miracle they managed to get some food. After a few weeks, the men were transferred to Rakishok. Women and children were sent to the Antanose village, about 5 km. from Obeliai where they were all murdered. Men were murdered in the Velniaduobe forest about 5 km. from Rakishok, together with Rakishok Jews and those of the surroundings towns. Mass murders took place between 15 and 27 August, 1941.

Only a few Jews survived, who had managed to escape to Russia at the beginning of the war.

|

|

| The mass grave near Antanose village |

|

|

| The plaque

on the monument carries an inscription in Yiddish and Lithuanian:

“Here the blood of 1160 Jewish women, children and men was spilled, killed cruelly by the Nazi murderers and their local helpers in 1941.” |

|

|

| The mass grave and the monument in the Velniaduobe forest |

|

|

|

The inscription on the plaque of this monument, in Lithuanian and Yiddish,

reads as follows:

“On this site, on August 15-16, 1941 the Hitlerists and their local helpers murdered 3207 Jews, men, women and children. Let their memory live forever.” |

Sources:Yad Vashem archives, Jerusalem, testimony of Bela Pasternak; testimony of David Cohen

YIVO, New York, Collection of Lithuanian Jewish Communities,

file 1541, page 69755

Oshri, Hurban Lite, pages 321, 324

Bakaltshuk-Felin, Meilakh (Editor); Yizkor book of Rakishok and Surroundings (Yiddish), Johannesburg, 1952, pages 292-305

Gotlib, Ohalei Shem, page 142

Julius, Rafael, Kamajai, Pinkas HaKehiloth-Lita (Hebrew), Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1996

Masines Zudynes Lietuvoje, Vol. II (Lithuanian), pages 213-214

Di Yiddishe Shtime, Kovno, 1.7.1932

The above article is an excerpt from “Protecting Our Litvak Heritage” by Josef Rosin. The book contains this article along with many others, plus an extensive description of the Litvak Jewish community in Lithuania that provides an excellent context to understand the above article. Click here to see where to obtain the book.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of the translation.The reader may wish to refer to the original material for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 07 Aug 2011 by OR