|

|

|

[Page 182]

by A. Lando

In Memory of My Brother Moshe, may God avenge his blood

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

The chesed institutions, from then and always, had a great part in the tractate of life in communities of Israel in each and every place, a faithful expression of the importance that Jewish thought ascribed to the attribute of mercy for the existence of the world, as is said: “at first God intended to create it (the world – A.L.) with the attribute of justice, but saw that the world could not endure and gave precedence to the attribute of mercy and partnered it with justice.” (Rashi on the first verse in the Torah).

So too was the matter in the community in Lida, which from the time that it was founded, established many and various institutions to extend a helping hand to the poor and the broken; permanent and standing institutions, in their purpose and their organization, from generation to generation, and some of them transient and changing, according to the need of the time. And the oldest among them that is known to us is –

Society of Undertakers (or, Holy Society), and, in the language of the members among themselves – “the Society.”

Indeed, you have no society in Israel that merited in the modern time (from the time of the first literature of the enlightenment) so many accusations of contempt as this society. And nevertheless, there is no disparaging the value of this institution on its own, and its merits in the independent lives of the Jewish community.

The initial purpose of the Society of the Undertakers was – the bringing of deceased Jews to a Jewish grave, and maintaining a cemetery. Who would volunteer for this important, yet unpleasant, activity, if not for the veil of holiness that the communal tradition has given it? And within the fulfillment of this holy duty, significant material power is given into the hands of the “Chevra,” since for its services it had the custom of collecting a variable payment from the heirs, all according to the financial situation of the family, and by these means it served the needs of the community and the need to assist individuals. It was a kind of indirect tax whose value to the community was great, especially from the time that the autonomy of the Jewish communities in Lithuania was nullified and the official right to impose direct taxes on its members was removed from them.

The Society's ledger was kept in Lida until the Second World War,[1] and included lists and protocols from 1831 until 1897. By the way, a previous ledger was mentioned in it, which was lost at the time of the fire in 1888 (before “the great fire” that was in 1891).

Details of the organization of the Society are known from that ledger, according to fixed and established regulations and, apparently, according to a tradition that was many years old. Every new member was obligated to bring in, within a limited time, 90 guilder (“gilden,” “zloty,” an antique Polish coin – 15 Russian kopeks), that is to say, 13.50 Russian rubles, a not insignificant sum in that period. Until he became a member with full rights, the new member passed through several stages:

But the men of the Society did not engage only in the burial of the dead. From the ledger mentioned above we see that many, for example, engaged in the care of the poor who were ill. And according to that which is remembered by us from the recent time, the means of the Society were used to strengthen various communal institutions, such as an “Elders' Residence,” a “Talmud Torah,” and the like. In another place in this book, we mentioned the matter of the acquisition of a new building for the Jewish hospital in the [18]60s.

There was a tradition in the Society of the “strengthening of the community,” and for the sake of drawing new members, to hold two banquet for the members each year: “The Great Banquet” in the month of Cheshvan, (it seems to me, for the Torah portion “Chayei Sarah”)[2], and “The Small Banquet,” on Shemini Atzeret.

Appropriately for an organization of the social weight of this one, the “Society” had its own synagogue, one of the most spacious and beautiful in the city. Among the worshippers in this synagogue were also those who were not from the Society of the Undertakers (just as there were Undertakers who would worship in other places), and among them some of the learned of the city and its notables.

The Lida Elders' Residence, which was located for only a few years “after the fire” in a new two-story building, even before the new Great Synagogue was established anew, testifies to the social sense of the communal leaders of the city. In the edition of “HaMelitz” from July 12, 1895, we find the article of the regular Lida correspondent, Zalman Yudelevitsh, about this important event, in this language:

“The foundation of the “Shelter for the Elders” (age sixty and up), a large and splendid house with spacious rooms and pure air. The elders will rest on distinguished beds, spread with clean quilts and pillows. Also the clothing that is on them will always be clean, and their daily meals will be given to them three times a day, besides the tea party twice a day.”

Maintaining the elders in this institution, according to what they convey to us, was free, and its budget was the responsibility of the Society of the Undertakers, the “Korovke” in its time, in the recent time, the Community Council and… special collections.

There was a Jewish hospital in the city many years ago, since there was always the worry for the sick Jew lacking means (the wealthy always preferred care at home). And in this the Jewish community without a doubt surpassed its Christian neighbors. Indeed, meagre were the means of the Lida community in the first days compared with the many needs, and it is no wonder, therefore, that the conditions in this important institution were far from satisfactory, especially from the time that the concepts developed and the recognition of the importance of hygienic conditions increased. And therefore, only when the community had the chance of a side income, in the year 1880 (burial monies in the amount of 3000 silver rubles, loaned at 10% interest), most of the total was dedicated to acquiring a new building for the hospital that served the Lida Jewish community until our time – when it became, according to an agreement between it and the local authorities, a municipal hospital, in which Jews and Christians alike were accepted.

Welcoming guests, a quality in which the Lida-ites excelled from time immemorial, found its institutional expression in the house for welcoming guests – which was intended in its time to provide overnight lodging to passers-by who did not have the means

[Page 183]

to pay lodging fees. In the last decades the number in need of this act of kindness diminished. But nevertheless, this mitzvah was not neglected, and an observant Lida landlord, the blacksmith Shmid, hosted this aforementioned institution – at the time of need.

“Kosher food:” The worry for the Jewish soldier found also in Lida “crazy ones” of its own from the time that Jewish soldiers appeared in the city. Indeed, in our time, not everyone would grasp the importance of this worry – to provide kosher food to the Jewish soldier. But one must remember that in those years, many were the Jewish soldiers that preferred to forego eating for the week and not to be defiled by treif food from “the king's foodstuff”[3] In an edition of “HaMelitz” from September 24, 1891 (that is, a few days before the outbreak of “the great fire”), we read about the founding of the soup kitchen for the army men that returned that same hour from summer maneuvers. The correspondent tells us about the local rabbi's (Rabbi Reines) sermon on the occasion of the opening of the fundraising campaign for the benefit of the new institution, on the topic: the love of humankind. He likewise informs us that the military authorities revealed a good understanding of the establishment of the kitchen.

It is not known to us who the bearer of the institution was, but in the year 1895 we read in that same periodical from March 12 the expression of “thanks and blessing to the honorable Sir Yitzchak Dzimitrovski for “his efforts in the matter of the kosher vat for the military men of the children of Israel.”” The writer knows to tell us that 4 soup kitchens were opened for the soldiers in all ends of the city, and daily there were given to them “bread to satiation without money, a full bowl of stew, a meat cutlet in the morning, and at night stew in fat without meat.”

The figure of Reb Yitzchak the Levite Dzimitrovski, may his memory be for a blessing, (Itche the White), was well-known in Lida. A learned Jew, honest and innocent. A childhood friend of Rabbi Yisrael Meir [Kagan], may his memory be for a blessing (the author of the Chofetz Chaim). The matter of “kosher food” (the name that Reb Yitzchak coined for the institution of his care), was not his only activity. In that same year, 1895, we read in “HaMelitz” about a second endeavor tied to Reb Yitzchak's name. And this is the language of the report:

“From Lida they transmit that not long ago a society was founded, “Tiferet Bachurim,” whose purpose is to plant sacred feelings among the tradesmen. Each and every day more than one hundred youths will be assembled in their special house, and they will listen to a lesson from the mouth of the honored Reb Yitzchak the Levite Dzimitrovski. The number of listeners continues to grow. If only other cities will see it and do likewise, to plant Mussar and knowledge of God in the hearts of the young tradesmen.”

|

|

|

|

But the life work of Reb Yitzchak remained “Kosher Food,” in which he continued, it seems to me, until the years of the First World War (1914-1915). He died at a good old age in the year 5691 [1931].

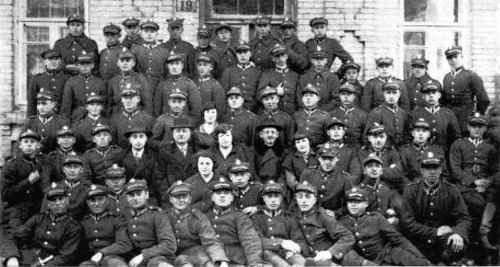

The worry of the Jews for the Jewish soldier in the Polish army, in the modern era,

[Page 184]

|

|

Seated from right to left: 1. The teacher Nizvodsky; 2. The functionary Michael Stoctor (the medic); 3. Not identified; 4. Ze'ev Sokolovski; 5. Not identified; 6. Elchanan Yishayahu Kaminetzki. |

found good expression in the festivals of Israel, when festive meals were held for all of those soldiers who were unable to travel for vacation to their homes and on the festivals were forced to remain in the barracks in Lida. The luxurious Pesach seders, with the participation of local functionaries, left a great impression on the soldiers that participated in them.

The Jewish Home for Orphans was established at the conclusion of the First World War, while war actions were still continuing between Russia and Poland. In the city tens of children who had been orphaned wandered around, and they did not have any remaining relatives who could take them in and see to their education. To the praise of the communal workers (and in the main, the women communal workers) who tended in this new and important institution, it must be noted that they fulfilled their duty with great dedication and effectiveness. In the pleasant two-story wooden building, on Kamionka Street (May 3rd) in which the institution resided, the little orphans found a warm refuge, which provided them with not only a place to live, food and clothing, but also a little warmth and tenderness, which were essentially lacking. Here they saw also to their education, in the Jewish educational institutions that were in the city, until their emergence into independent lives. The name by which the new institution was called upon its founding, “Herzliya,” would testify to the spirit that its founders sought to prevail within it.

Over the course of time the Jewish Women's organization in Lida accepted the institution under its auspices. The women were not satisfied with the special fundraising campaign that they conducted regularly for the benefit of the institution, they also personally visited it frequently, and oversaw the work arrangements in it and the care of the children. A special affection was known for the institution by the Lida public, and the Chanukah banquets that they held between its walls, with implementation by the children themselves, always won great success, and also, respectable income.

Maot Chitim (flour for Pesach) is an ancient activity in all the dispersions of Israel, intended to provide food needs for the festival of Pesach for the poor of the community, and so it was also in Lida. Already in the month of Adar the activity began, with the religious groups engaging in the mitzvah, which were concentrated around the Rabbi of the city, and many needy families got a holiday table thanks to this special, one-time help.

And thus was a pearl in the mouth of Idel Gilmovski, one of the Lida jesters of the generation: “When the festival of Pesach is approaching, I have nothing to worry about except for a turkey. For matzot, I have nothing to worry about: would it ever enter your mind that they will leave a Jew to remain without matzot for the festival of Pesach?” So he expressed, humorously, as was his way, his appreciation for this fine activity of mutual aid.

“Beit Lechem,”[4] “Giving in Secret” - This activity came to extend help to the needy in the form of sending food packages, each week throughout of the year, especially to those families who became impoverished due to the socio-economic changes and who were embarrassed to hold out a hand to request aid. A son of our city, Mr. Yaakov Levin, told us about the activities of this organization, “Beit Lechem,” in a separate note.[5] Mr. Yaakov Levin served as secretary of the organization for years.

The Gemilut Chasadim Fund – These were next to almost every synagogue in the city, for the assistance of the worshippers who were in need of a small short-term loan in order to overcome a temporary difficulty in payments, for special needs in the family, in the event of an illness, and the like. These funds were also next to various secular organizations, and likewise there were private Gemilut Chasadim funds.

And as an example, a Gemilut Chesed fund that was administered by Reb Yossi the Sofer, may his memory be for a blessing (Yashe the Scribe). Reb Yossi's son, Mr. Sol Finestone, may he be distinguished for long life, from New York, who visited in the city of his birth before the Second World War, founded this fund and placed his father as its trustee and administrator.

We will mention at this opportunity a son of our city, Yehudah Shifmanovitsh, may his memory be for a blessing (who was one of the founders of the glass factory “Gavish” in Rishon Letzion), who passed away in the year 1937 and was brought to rest in Lida. Before his death he bequeathed half his wealth to found a Gemilut Chesed fund in Lida, and as trustee of the fund he appointed the local rabbi. Meanwhile the war broke out…

[Page 185]

We brought the few details that we remember about the Gemilut Chasadim fund in Lida that reflect the relationship of the members of our city to this mitzvah: “Now when your brother sinks down [in poverty] and his hand falters beside you, then shall you hold him… and he is to live beside you.”[6]

“Craftsmen:” I wonder if many of the members of our city and our generation still remember a society in Lida with this name. This was a society of one man, and his name was Reb Yitzchak Yeruchmanov, may his memory be for a blessing. He was the initiator, he was the fundraiser, he was the collector, and he was the one who engaged daily in this sacred work, which was to gather abandoned children who lacked education, to see to their education in Torah and in work. Memories of this dear personality are listed in this book, in a different section.[7]

Tending the Sick: This society was the creation of Reb Neta Shluvsky, may his memory be for a blessing, and its goal is testified to by its name – help and caring for impoverished sick people. Previously the matter was among the duties of the Undertakers' Society, and apparently over the course of time the need was felt to found a separate institution to increase the activity. There was a special Shabbat for it, for “the strengthening of the Society,” (if I am not mistaken, this was Shabbat “Vayera,”)[8] in which the members were invited to a shared festive meal, discussed the activities that would be done, and on the plans for the future.

“TAZ” was a society born of the modern era, a branch of the TAZ Society in Poland that acted greatly for the protection of the health among the Jewish population in Lida. Among its main activities there must be mentioned the summer colonies for children from families lacking means. There were representatives of various groups, without party differences.

Outside of the societies with names that indicate their character, on the Jewish street in Lida there acted tens of “private” philanthropists and charitable women, to whom all the broken-hearted found their way. Who did not know Rache the Krupnitze (Rache the Groatser)? In any case, many downtrodden women knew her abode in the market, in the cellar of Meir Steinberg, in which was her dwelling place along with her groats shop (from here is her mentioned name). She did not conduct fundraisers, and did not print announcements. But when a woman came before her in an hour of need, she found in her an open heart, and also, the open bag of groats and the open bag of flour. And within an hour, Rache went from shop to shop, and in her hand was a red kerchief that got fuller and fuller with coins of varying amounts, and the woman did not go out empty-handed.

Moshe Kalman the Butcher found a special field in which to define himself. When Reb Moshe Kalman sat at his table on Shabbat, he couldn't free himself from the disturbing thought that at this hour there sat on Kamionka Street, in a white building, behind a lock and bolt, Jews who were driven crazy by the circumstances of the time and were sentenced to imprisonment. And if on all the days of the week it was bitter for them, the feeling of loneliness was sevenfold bitter on the day of Shabbat. If they sinned, they earned their punishment. But to also take from them the feeling of Shabbat – that is a sin for us. What did he do? He took two large baskets and every Shabbat in the morning he would go to every Jewish house and request challahs, half-challahs, or even a slice of challah, for the Jewish prisoners. And when the two baskets were filled, he would direct his steps up to Kamionka Street, with difficulty carrying his heavy load, to the municipal prison, a place where the jailers knew and favored him, and the gates of the bleak institution were opened before him. Ren Moshe Kalman was a sickly Jew, and weak in the legs. Nevertheless, all his days he did not stay his hand from this mitzvah that he chose, in his seeing it as a special mission, or in the language of the members of his generation, his portion of the world to come. We will conclude this meagre survey (meagre – compared to the great number of the tzedakah societies of various kinds and private philanthropists that functioned at various times among the Jews of Lida and which, to our sorrow, did not survive in our memory), we will conclude it with an additional example of the worry that the Jews of Lida dedicated to the poor of the city, which we found in the periodicals from the year 1881.

The subject of discussion was a society that called itself “Bread for the Poor,” whose purpose was to bake bread and sell it cheaply – “2 kopeks a pound,” for the poor of the city.

The word “philanthropy” we are sometimes accustomed to express with a tone of contempt. Indeed, we must not forget the fundamental meaning of this word – the love of human beings. And how much mental energy, how much feeling, did they invest in these acts of tzedakah and lovingkindness for the benefit of the Jewish community, the bearers of conscience of the community, which, according to the degree of their ability, they attempted to bind wounds, to diminish pains, and to fix, to the degree possible, that which disrupted the defective world order which their hands were unable to change. And if times and new ideas arrived, they gave wings for them in Jewish society for a fundamental repair in the Jewish lives and for repair of the social order in general, behold their inspiration also came to them from the same ancient source – the love of Israel, the love of humanity.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yaakov Levin

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

In the public life of our city Lida, the social institution by the name of “Beit Lechem” held an honored place for the support of the poor.

Thanks to the initiative and the devotion of individual activists, the exalted institution held on until the outbreak of the Second World War. Each week, on Thursday, at 5:00 in the afternoon, the distribution of support to the poor of our city began with the help of volunteers – members of the committee who were chosen at a public assembly.

The place of the distribution was a room that was next to the prayer house of “The Undertakers” that we received for this purpose from the synagogue gabbai. The basis of the existence of “Beit Lechem” was:

[Page 186]

Apart from the weekly distribution, there were also urgent exceptional occurrences: a whisper alone in the ears of one of the members of the council about a Polish family that was found in a difficult situation was enough. The help did not delay in coming on the same day.

There were instances when they did not transmit the support directly to the one in need. They sought ways for the “package” would arrive at the place circuitously, so as not to hurt the honor of the family, to prevent offense and bloodshed… in such a way tens of Lida families were saved from hunger and anguish.

The portion of the weekly distribution contained: a. groats; b. meat; c. potatoes; d. salted fish, bread. In special instances also butter and milk.

On each Shabbat eve we would turn in “A Voice Calls for Help” in the weekly newspaper “Lida Week” (which appeared every Shabbat eve under the administration of the Editor Mr. Bernholtz, the Director of the “Tarbut” school), to arouse and seek the help of the public to support the “Beit Lechem” institution with a generous hand.

I remember, once before the festival of Pesach, the cashier of “Beit Lechem,” Mr. Benjamin Landa, may his memory be for a blessing (owner of the Grand Hotel), appeared at my place, and let me know that the institution's fund was empty. And the festival was getting close. “There is no other choice but to go out to collect donations from “the whales of the city.””

I left my business and together we put our feet on the road. We started from Sovalski Street: the first house that we entered was the house of the Shapira brothers, may their memories be for a blessing (a casting factory), and without our needing to speak much, they extended to us a fine portion: “Please don't publicize the amount…” Afterwards, the “Erdel” factory, the casting factory “Banland,” the “Drot Industry” factory, the “Metal” firm, the Pupko and Pfeffermeister beer factories, the sawmills and flour mills – within a few hours there was in our hand a respectable amount that was enough for the purchase of all the needed groceries for the distribution of the approaching Pesach festival.

In this way help came to the poor unfortunate people.

Twelve years I worked as a volunteer as the secretary of the “Beit Lechem” institution in Lida. I had a great privilege in remaining alive and being able to bring up these memories of our city Lida. These lines will serve as an eternal monument to the exalted devotion of the other people of Lida.

by Yehudit Ganuzowitz

Translated by Roslyn Sherman Greenberg

The society “Toz”, which was founded not long before World War I in Peterburg, started their activities in Lida at the end of the 20's. Their goal was to raise the hygienic conditions of the Jewish population and they branched out to do preventive work, although not always enough, in view of the need. Their director was especially interested in the welfare of the children. Poor mothers were given all the necessities for the birth of their babies. There were distributions of Fishtran which was a resource against tuberculosis and other childhood diseases.

In the summer months, the “Toz” set up summer colonies for the children. First the colonies were in Roshlaki and later in Mailaikietshizne, and were called half-colonies because the children would come in the morning and return home in the evening. In the last year before the war the children would gather each morning near the office of “Toz”, which was on Suvalki Street, in the house of Tziderowitz, and there a bus would come to take them to the colony. In the evening they would return by foot with their teachers.

In Novoyelenie, not far from Lida, “Toz” established a colony where children would stay overnight. From poor cities and shtetls children would come there to rest and have a good time. In a large, two-story wooden building, which stood in a pine forest, separated from the surroundings, in summertime happy children's voices would resound in play, laughter and song. There they would bathe in the nearby stream and take part in numerous discussions and lectures with their teachers and educators.

The committee of “Toz” in Lida consisted of : Dr. Zartzin, female Dr. Ogushewitz, the teacher Peresetzki and others. The Secretaries were Chana Chasman and Sonia Verskaya.

by H. Jijemsky

Translated by Jack Shmukler

Lida was among the first cities to found a division of the organization “ TOZ “for the purpose of safeguarding the state of health of the Jewish population.

The founders were (fem.) Dr. Ogushewitch, Dr. Zartzin, and Mr. Peresetzki – Later on Yablonski, Rudi and others were elected onto the committee.

The organization commenced operations by opening a consultancy service for breast-fed children, in one of the houses of the Jewish hospital. Dr. Ogushewitch was the consultant for “Drop of milk “and Miz Sonya Verskaye was the first social (sister) worker as well as the secretary. Later on as the scope of work increased, my sister Gite Khasman (later Gite Nyeprovska) was employed as social worker, and after that my sister Miriam Khasman and myself till my departure for Eretz Israel in the year 1938.

The main purpose of the “Drop of milk “was to instruct young mothers how to care for and bring up the new – born children. At first only the mothers from the poorer section of the population would attend – They would receive garments as well as medication and other products for the breast-fed children. But within a short space of time the activities (services) of “TOZ “expanded rapidly and the mothers and children from all sections of the population frequented the “Drop of milk ““ TOZ “also branched out in the field of prophylactic work.

The activities of “TOZ” were growing apace, and in time they hired large premises – At first from Mr. Levinson, then from Mr. Tziderowitch and lastly from Mr. Frenkel in Polkovske street. A Dental practice for the treatment of school children was opened where they were treated free of charge or only a token payment.

|

|

|

|

| Summer camp for Jewish children from Lida organized by “TOZ” in Rashlaki |

A milk kitchen was opened where they prepared bottles of food to feed the breast fed children and every working mother, or those who couldn't afford it, would receive – each morning, prepared bottles for the entire day.

“TOZ” had ties with all the school administrators wherever Jewish children were taught. Doctors from Toz examined the children and the weaker ones were sent to vacation camps. They also distributed cod liver oil and other medicinal preparations. They also had a food program where the school children, would receive on a daily basis, a bulke with milk or cocoa. During holiday months Toz organized a summer camp. At first they used to hire rooms, afterwards Toz constructed their own buildings. The poor children would take part in social activities till 4 – 5 in the afternoon. They would enjoy the outdoors and fresh air. They were supervised by qualified teachers and educators.

In Novoyelna “TOZ” built a double storey building in the middle of a pine forest. At this camp the children would socialize and enjoy themselves for a whole month far from city life. It was one of the most beautiful places where the poor children could enjoy themselves, thanks to the work of “TOZ”.

“TOZ” became immensely popular and the majority of the population from all walks of life – mothers, breast fed children, pregnant women, school children, rich or poor all enjoyed the benefits of the various branches and services offered.

It was a place where all sections of the population could meet and mingle – “TOZ” truly became a major social factor.

[Page 189]

by A. Lando

Translated by Jack Shmukler

Who among those born in Lida at the end of the last century or the beginning of the present does not remember the fear that descended, when in the middle of the night the loud sound of the firemens' brass horn would penetrate the tightly closed shutters, the half dressed men and women, terrified, milling around in the night darkened street, looking up at the red tinged sky, trying to guess where the fire was. Here and there a fireman would appear, fireman's hat in one hand, buttoning up his uniform coat with the other as he hurried on his way. After awhile one would hear the rattle of steel rimmed wheels on stone cobbles – The wooden water barrels on two wheeled carts were on the way.” Where is the fire?” The firemen race off in the direction of the red painted sky. (There were no telephones in those days)

If rumour had it that it was a brick house then we would be somewhat reassured. The situation was much worse when fire broke out in a neighbourhood with wooden buildings and in particular structures with thatch roofs (there were still such houses in Lida at the time). It was horrifying to see such a fire. If a thatch roof caught fire, it was pointless to pour water; the roof should be pulled down with steel hatchets, as soon as possible and the burning straw and embers put out on the ground More than once it happened that a ball of burning straw would break away from one roof, and carried by the wind = like a bird of fire – land on another roof made of shingles or straw. In this way the fire would spread from house to house and in a few short hours the whole street was up in flames. (Smoke) Some of the old-timers (may they live to be a hundred and twenty) still remember the big fire of (1891) when almost the entire city was destroyed. That was not the first fire in Lida, there were a number of previous fires.

In the past Lida endured many wars and each time the fires left the city in ruins. In olden days: - when Duke Vitavt captured the castle (it was unlikely that Jews lived there at that time): later on when the Tartars attacked the region in 1506; after that when a large army of the Russian Tzar Aleksey Mikhaylovitch captured the castle and city in 1659

On a summer evening in the year of 1679 a horrendous fire broke out (cause unknown) and in a matter of 1 hour 38 houses belonging to Jews and Christians were burned down. Many of the people (townsfolk) both Jews and Non Jews who didn't manage to get out of the burning houses, perished in the flames and many others received severe burn injuries.

Another huge fire occurred in Lida in 1843 . It started in the public baths and rapidly spread to the surrounding areas. The entire synagogue courtyard, a part of the market place and the whole of Vilna street burned down.

The most horrific fire within living memory that occurred in Lida broke out at the end of the first day of Sukot in 1891 . Nearly the whole town went up in smoke. About a thousand dwellings. Almost all of them Jewish (only 17 belonged to Christians): 400 residential houses, 600 “Cold Buildings”, barns, shops. “The Big Fire” would be long remembered by the Jews of Lida and was used as a basis for dating events – “so many years before or so many years after the big fire”.

In that same fire – not counting the old wooden built shul – nearly all the kloyzes (houses of prayer) with the exception of the tailor's burnt down. The city “Ratush” which was situated in the market place – a colonnaded building that was built in the 18th century and served in later years as a guard house – as well as a timber structure built in the gothic style which was used as a firemen stable – were also destroyed in the fire.

Lida's volunteer firemen group(Fire brigade)

So go and sign up

For the fire brigade

And put on a red uniform.(a Jewish cabaret song )

[Page 191]

|

|

|||

| Fireman's orchestra | Fireman's course in 1926 |

|

|

| Firemen in Lida |

|

|

| Cast metal emblem of the 40th anniversary of the firemen in Lida 1832-1932 |

[Page 192]

by Abraham Gelman

Translated by Phillip Frey

|

Until quite a bit of time after the first world war the Lida Firemen's-Command was composed of 4 or 5 pairs of horses, wagons with water barrels and several hand-powered extinguishers. We must remember that at that time there were still enough wooden houses in Lida, easily combustible. Roofs, partly tin or of thatch, or many covered with wooden shingles, and fires were no rarity. I'll mention several instances of the worst fires.

The fire on Zavalne street began at the ritual-slaughterer's house, which spread and more than 30 Jewish houses were burnt down, nearly all uninsured, except for the slaughter's house, mostly the houses of poor Jews.

A severe fire that claimed two human fatalities, took place in the oil-factory. The fireman-Mair Gorelik was severely burned in its course.

I recall also the fire in the old “Nirvana” cinema (In Dluskin's courtyard) which threatened a severe threat to the wooden structures of Lida Street.

Several tens of meters for there were great stores of wooden materials from Gedalioh Feinstein's carpentry.

An indirect victim of the improper construction of the wagons was Elie (Eltschik) Lande (son of Benjamin Lande of the “Grand-Hotel”): wishing to jump up on a wagon, which was moving, in order to ride along to the fire, as was the custom, he slipped and was killed.

In short, the time came to modernize the equipment. Max Poliatshek, one of the most able members, dedicated himself to the matter with much energy, partially neglecting his private business, and finally, after several years of exertion, the Lida Fire Team was outfitted with fine motorized equipment, 4 trucks, with water tanks, a motor-pump, etc.

Formerly there were assigned five paid firemen, who lived on the site, and order that they could right out on the first call. The volunteers naturally came along later, each from the place where he found himself at that moment. The five appointees learned to drive and that understandably increased the possibility of getting to the place on time, before the fire was able to spread.

All of this cost a lot of effort and money, and since the town administration was always had a deficit, they had to look for outside support. The firemen used to put on shows, balls, dance evenings and the like. Here must be mentioned the firemen's' orchestra, which helped a good deal (The conductor-Shloime Zalmen Miednitski). There was also a special monthly payment for the firemen's-command

In the years 1935-1936 a womens' section was added to the firemen's association, whose function was to provide emergency medical help in a palce or in the event someone had been injured or burned at a fire. This was a group of 15 young women, under the direction of Ms Svaviatitski (from May 3rd Street (Drei Mai Gas)),who had completed a special course.

The workouts by the members used to take place weekly and were obligatory. The members of the orchestra (which also had to participate in the regular firemen's practice.) had twice-weekly exercises.

The firemen's-association had its own club, which carried on cultural activities.

A bit of disharmony in the firemen's cooperative activity between Jewish and non-Jewish firemen in Lida was Caused by the Grablis brothers and another pair of Polish members, anti-Semitically disposed, who wish to get control of the association. The Jews wouldn't allow it, and after many court sessions, often stormy, a decision was reached which divided the association into two commands: “Group 1” was responsible for the city area up to the railroad tracks and “Group 2”, under the direction of Mikolai Grablis on the Slobodke area, on the other said of the train tracks. This was a small and less well-schooled group. In that area there were nearly no Jews. In cases of a severe fire on Slobodke, the first, city group, was not just one time called out by the Burgermeister,Zadurski,or by the police-chief.

September First, 1939

In the first days of the Polish-German war, the members of the firemen's association found themselves day and night in the locales of H. Miklashevitsh, Zamkova street, and the wee called out every short time, after the bombardment by the murderous German airforce on the Lida population, which suffered dead, wounded and many fires-up till the 17th of September, when the Polish might and the Polish army abandoned Lida. More than 30 hours the town remained without any sort of control.

By the initiative of the Jewish populace, the town Fire-Command stood on watch not to allow any attacks, robberies or thefts. On the train station stood full truckload of various merchandise, which had recently arrived for Lida merchants, and part were stolen by the Polish population., who lived nearby, on the farm and on Slobodke. The Lida firemen were armed with cold weapons and often chased the robbers and theives. What can several tens of people do against thousands! Therefore we had an interest mainly, insofar as possible, to prevent pogroms on Jews and murders, until a measure of order was restored. Rumors were circulating, that the Russians were going to assume power.

When the Russian army took the town, a new firemen's-command was created, one that was paid, on the Soviet pattern, under the direction of a “Politruk” (A Russian Jew). Many of the former Lida firemen joined the news command. Many of them were, with the outbreak of the German-Soviet war, evacuated, with their trucks, to Russia.

[Page 193]

by T. Tsigelnitzky

[our volunteer translator wishes to remain anonymous]

The Butcher's Synagogue was one of the most beautiful synagogues or Beit Medrashim on synagogue hill. Most significant were the artistic drawings created by the renowned Lida artist, Tager, who created them according to the directives of the active leaders of the Butchers' Synagogue. The Shamesh of the synagogue was R'Zundel – a slender Jew with a small thinly whiskered black beard. Always on the run – never had any time. He did everything even though he was the shamesh of the Butcher's synagogue. It was quite a job to make a minyan during the week. He would be quite a sight He would stand at the entrance with his Tallit and Tefillin and would stop every passerby and tell them they need only one more person for a minyan. No one could say no to him – tell him they have no time – before they knew it they were already inside in the Beit Medrash. Zundler had a two part task – to stand in the door blocking the exit after all the work to get the person in all the while still getting someone to come in – 8 more Jews. And again he repeats the same thing. Only one more Jew is missing and the proof is that I (Zundler) am already in Tallit and Tefillin; all ready to pray. Because of all that effort on Shabbath and Holidays his task was not so arduous. Butchers on their own came to pray. Dressed in holiday garb you felt you were among your own and had a common language. During the “layen” period, the men would speak in Polish telling each other tales of the week past –, who bought a bargain at market (a calf at a good price) who got a good bid for a cow. The chatter went on until the Gabbai interfered by asking for quiet in order to pray. The congregants go in to pray.

[Page 194]

by Yitzchak Ganuzovitz (Ganuz)

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

I will mention my Grandfather, Reb Eliyahu Baram, or Reb Eliyah the Professional, as they called him in the city. A noble figure of a God-fearing and righteous[1] Jew is revealed before my eyes, in whom manual labor, keeping the mitzvot, and folk simplicity were joined together, and crystallized his character and his personality.

Grandfather was short-statured, his shoulders were broad and a little hunched, since his burden of carrying the public weighed on him, and he leaned into these shoulders of his without dropping the burden. He had a builder's arms, which it seems were smelted from iron, which had learned to grasp wooden beams already in his youth. He had a white beard that descended to its full length, yellowed at the roots from much “smell tobacco” [snuff], and its end was hidden in the opening of his coat.

Reb Eliyahu Baram was born in Lida in the year 1856 and passed away in the year 1934. After the great fire that visited the city and turned its wooden houses into a mound of ruins, he was, with his cousin Reb Matia the professional and his cousin Reb Eliyahu, among those who built as contractors its new houses, especially the streets that descended from the central “Vilna Street” towards the Lidzika River and kissed its quiet and muddy banks. The houses were built with his own hands. With his own hands and by the hands of Jewish and Belorussian professionals from the adjacent villages that he hired as contractors for a daily wage, in order to fulfill what is written “and the wages of a hire shall not rest with you overnight.”

His brothers and his father were all builders. Their praise is on the beams of a house that stand straight, on a tiled roof that is built as it should be, on a beautiful balcony that captures the eye, and its open door that rotates on a hinge, inviting every Jewish guest passing by to come and enter.[2]

Reb Eliyahu belonged to the “Tehillim[3] Society” and to the “Chevra Kadisha” in the city. On Shabbat, in the early morning hours, a time when silence prevailed in the Jewish streets and all of them were sunk in deep sleep after a week of hard work, he would walk around in the streets and awaken the residents: “Jews, get up to say Tehillim.” When they delayed in getting up he would return and awaken them a second time. On days of ice and snowstorms, days of strong autumn rains, days of changes of government and fear, riots in the city - he stubbornly continued this walking of his without hesitation and without fatigue.

In the days of the war with the Poles they conquered the city with their defeat of the Bolshevik garrison, and began to riot against the Jews, who were suspected of communism. In those days, and these were the days of Pesach, 39 Jews were murdered by them in the various approaches to the city, and most of them next to the Maloyskszczyzna Bridge (among them: Letuta, Koren, Movshovitz, Rozenstein, Kamionski, Morshtein, and also Jews from outside of Lida). Every Pole had the right to point out that a Jew was a communist. Among these that informed the Poles on those that were taken out to be killed, was the notorious daughter of the Pole Tovlevitz – the pig slaughterer from Lideska Street. Then many Jews were also murdered on the roads that led to the city, and Reb Eliyahu was travelling with waggoners, gathering the murdered dead bodies and bringing them for Jewish burial.

In the first days after the conquest of the city Reb Eliyahu Baram turned with Rabbi Aharon Rabinovitz to the Polish ruler, and requested that they be permitted to take the dead bodies of the slain Jews out of the Christian cemetery and bring them to a Jewish grave, and that they would turn over to them the bodies of the Poles that were buried in the Jewish cemetery. The Commandant asked the Rabbi: Who are you? The Rabbi answered that he was the Rabbi of the city, and the second was the representative of the society that takes care of the cemetery. The Commandant did not answer them at all, and commanded the soldiers to take the two of them with them.

The soldiers were armed with their weapons, led the two of them by way of the central street in the direction of the Yashmentis area, and a suspicion stole into the heart of those being led that they were being led to be killed.

As they passed across from the house of Simlevitz, who was a judge and an educated and enlightened Polish person, he stopped them and asked the soldiers where they were leading these Jews. They answered that the Commandant had commanded to kill them.

Free them – he requested - I am a Polish judge and a pious Catholic and I ask you to free them. Do this on my responsibility and I will contact the Commandant.

He invited them to his house and after a discussion the soldiers left and went away from the place.

After some time Reb Eliyahu sent a few of his Jewish workers to check the broken tile roof of Simlevitz's house, and as a sign of thanks and appreciation they covered the roof anew. The judge wanted to pay for this work, but Reb Eliyahu refused to accept the compensation.

The rough, manly voice of my grandfather, that rang out like hammer strikes on iron nails, I would discern immediately in the hustle and bustle of the alley. From afar I would hear as he drew near to our house, and I would stop the heat of the game, and run home. “Mother, the hat, where is my hat, Grandfather is walking.” I knew that if Grandfather met me with a bare head, he would chastise me with harsh words, with a short but penetrating a moral rebuke. “A goy goes without a hat. We, we are Jews.”

A malignant disease brought Reb Eliyahu low but it did not crush him. With faith he would die a tzaddik. On one of the wintry Shabbat days in the afternoon he sat in his house, which bordered on the “Tiferet Bachurim” kleizl, head bowed over the head of the table, and whispered his prayer, his face was pale and drooping, gripped by the agony of the illness. His eyes bulged out of their sockets after long months of suffering and insomnia. I entered to visit him straight from the kleizl, and I was a student in Grade 2 of the elementary school who was already beginning to be proficient in the paths of the Hebrew language. The structure of its sentences and the combinations of its words were beginning to become clear to me each and every day.

Sit – he said to me – sit here next to me. His voice was shattered, weak, entirely rasping. I agreed and sat myself next to him. He picked up in his hands the prayer Siddur that lay closed before him and offered it to me. Terror gripped me at the appearance of his hands that were as white as the snow outside the window. Their bones and their veins protruded as if they were going to burst out and cry bitterly about the strong body of a person that was shrinking more and more in the face of the storm of the destruction.

He opened the Siddur to a place that opened without leafing through its pages, yellowed from many years and much use. Read - he whispered to me - read here!

I began to read. One sentence, a second sentence. Slowly but surely, and clearly, I pronounced the verses in the book of Tehillim that he opened before me. I read in the Sephardi pronunciation that flowed for me from school. He pondered a little and suddenly closed the book as he had opened it.

[Page 195]

His voice wore something of the metallic quality that was known to me, and he finished his verse that was mixed with satisfaction and endless happiness: “very good, my grandson, very good. Now I can die already.”

My grandfather had already been preparing to die for some time, like a person who is packing his suitcase and waiting for the bus in the proper place in the bus station, who expects the coming of the one that will take him to his desired destination. He prepared shrouds for himself in advance. From his savings he paid for a tailor, so that his sons, God forbid, would not need to bear these expenses. To mark the occasion of the acquisition of the shrouds he prepared a kiddush in his house. Like a minyan of worshippers, his friends from the synagogue assembled in his house, raised a cup of drink, and wished him length of days of health and happiness. Someone told about one of the elders of the city who three times ordered his shrouds for himself when they wore out from being in the closet for too long, and this one their owner is alive and well, his moisture has not fled,[4] his strength is with him, and his hand is extended to give tzedakah to every poor and needy person. Grandfather sat at the head of the table. His head was bowed and his face was as pale as his white beard, which was somewhat unkempt. His eyes were shining and tears as large as drops of rain before a snow were flowing onto his wrinkled cheeks, falling down onto the pages of the thick Siddur that was before him, which were absorbing the happiness and the grief together.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yitzchak Ganuzovitz (Ganuz)

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

The religious youth association “Tiferet Bachurim” was founded in Vilna at the end of the 19th century and in that same period it was founded also in Lida. Its aim was to organize the novice workers and to bring them closer to Judaism, to Torah, and to tradition. After about twelve years a group like this also arose in Lida. Its first initiators were Reb Yitzchak the Veisser (Wise One), a scholar and learned person, and so too his two students, young men who were shoemakers who were known for the sharpness of their intellect, the purity of their way, and their knowledge of Talmud.

These young men were Reb Eizel the Shoemaker and Reb Mordechai Kalmanovitz. In “Tiferet Bachurim” after the work hours they used to hold evenings of homilies and lessons in Tanakh, Talmud, the history of Israel, and also discussions on matters of Mussar and society. Teachers of halakha from the yeshiva of Rabbi Reines took an active part in these lessons, and among them was also the teacher and writer Pinchas Schiffman Ben-Sira.*[1]

I would like to tell about the kleizl as I remember it from the years before the outbreak of the Second World War. The kleizl bore the name of the youth association “Tiferet Bachurim,” because members of this association founded the kleizl, and the elders of its worshippers in the [19]30s were among its founders from that time. The Beit HaMidrash was found on “Peretze” Street. “Peretze” Street was for the name Y.L. Peretz, for indeed practically all of this street was settled by Jews. After the First World War at the time of the Polish regime, they changed the name from “Politcheina” or “Policeskaya” to the name “Peretze.” The previous name remained as an anachronism that only the elders of the generation used, as a cloudy memory of the brick house that was at the top of the street, which in the days of the Tsar's regime served as the place of the headquarters of the “Politziya,” which was the local police.

The kleizl “Tiferet Bachurim” which was built, approximately, in the year 1910, dwelt in a wooden house with one story and a “shalke” - an apartment in the attic. The kleizl was in another part of the house; in its second part there lived a few families. One entered the small courtyard by way of a narrow gate, and a bench stretched for the length of the courtyard was parallel to those arriving. On Shabbatot and festivals this yard was full of children who came here with their parents to say their prayers, and the sound of their play, their conversation and their speech echoed from here to there.

A large wooden bima stood in the center of the Beit Midrash, near the amud. In between the bima and the Aron HaKodesh, on the ceiling that was above them, was an opening in the shape of a rectangle, and there was the women's section. The women sat in a room that was in the attic, blocked by a divider made of carved wooden boards that surrounded the opening, and listened to the gaiety and the prayer. On the Aron HaKodesh was a parochet whose light blue color was already faded. It was nearly certain that the Aron HaKodesh was full of Torah scrolls, for indeed on top of it lay a collection of small Torah scrolls; these were the Megillot[2] that they used to take down from there twice a year. Once at the fixed time for reading, and a second time for Simchat Torah, the time that the Gabbai would honor youths and children with them for the hakafot.

Two long tables stood along the length of two walls, the western and the southern walls, which served, in addition to being a fixed place for the worshippers, as a place for learning for the Mishnah society, and at a time of need also as a place for refreshments, or for the collection of donations in porcelain bowls on the day before the day of judgement.[3]

Above the table on a shelf that protruded from the wall, stood a large silver menorah whose eight branches shone with warm bright light on the long cold Chanukah evenings, a time of frost flowers and traces of ice covered the small windowpanes of the kleizl's windows.

In a corner of the western wall stood a stool, and on it was a bucket of water and a cup made of copper hung on a small piece of string, a basin and a towel, and anyone who needed to wash their hands could come and wash. A large potbellied oven was also there, with benches around it. A guest that came, or a needy person who would chance upon this place and not find for himself a place with one of the “householders” would spend his night here on the bed of these benches, next to the broad and beloved stove. In the years [19]39 and [19]40, a time when Jewish refugees arrived

[Page 196]

in their multitudes from the regions of western Poland, in their fleeing from the Nazis, a number of families always found here a refuge and a shield.

Next to this wall there also stood the closet of “names.”[4] Worn-out pages from holy books, sections of moth-eaten ancient books, tatters of lamentations, supplications, and books of Mussar soaked with the tears of their learners and devotees. Ragged books of Mishnah and Kabbalah whose letters were faded with much time, and among their yellow-grey pages you could find a white hair that fell sometime from the beard of a diligent one, in the heat of the moment, and in a torrent of words of contemplation, argument and debate. And above all, “the way of the world precedes Torah.” Letters that are printed in curly handwriting proclaim this on an announcement hung inside this cabinet.

Reb Eizel the Shoemaker was the spiritual image of the kleizl “Tiferet Bachurim.” He was a short person with a noble countenance, with a white beard that descended its full length. Eizel the shoemaker's livelihood and sustenance was from the work of his hands, and only from this. He was proficient in his work and a master of argument in the sea of the Talmud and the decisors. He had a gentle soul, and was quiet and modest in his ways and his contacts with people.

On Shabbatot most of the time Reb Yaakov Eizikovitz, a young person with a clear and pleasant voice, would pray before the amud. With the conclusion of the prayer children would gather around him and sing “Anim Z'mirot” together with him:

The head of Your word is truth,

Calling from the beginning,

Every generation with those who seek You.

When they reached the word “truth” they would stop the melody of their song and voice this word with a loud and boisterous yell, together with the whole congregation of worshippers.

Simchat Torah was the most especially beloved for us, the children. On the evening of the festival the kleizl was full from here to there. Here Reb Binyamin Baram the glazier was arriving. He only entered the entryway of the house, announcing with a yell of happy gaiety and satisfaction: Holy Sheep!! And the children would respond to him: meh!!

In the drawer of the bima table were percussion instruments and cymbals. On this evening they would take them out. With the devotion of the joy of the dancing, with the Torah scrolls hugged in their arms, striking these cymbals with the beat of the song:

Compassionate father, hear our voices,

Help all Jews,

Compassionate father, hear our voices,

And among them,

Let there be redemption,

Let there be salvation,

Let there be redemption.

May the Messiah come!

The circle spins and goes with tapping feet, with clapping hands, with a song of yearning that erupts from the depths of the heart and soul and faith as strong as life – our righteous Messiah will surely come.

|

|

| The Ein Yaakov Society of the Chassidim of Liady (5687) [1927] |

Translator's Footnotes:

[Page 197]

by Chaim Amitai

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

Reb Yosef Vinkovski, known as “Yashe the Medviedz” (The Bear)

His form stood tall as a sturdy oak. I remember him when he reached the age of seventy and more. His broad body and his head that matched his body's dimensions, almost without a neck, merged into one block. He would step slowly and surely, with his feet placed in heavy boots during the course of all the days of the year. He had blue eyes; he was nearsighted and cross-eyed, so that I never knew in whose direction his gaze was turned. At the time of prayer he would bring the siddur really to his eyes, and from the mouth of the one with a sturdy body a thin voice would emerge. When they heard his voice without seeing him, it was possible to suppose that it was the mouth of a child that was speaking. Despite his nearsightedness his self-confidence was immeasurable.

On one of the days, between Mincha and Maariv, a group of worshippers sat around the great oven in the butchers' kloiz, and brought up memories from days gone by. Among them sat the “Medviedz,” and told what once happened to him. All of them sat open-mouthed, and with attentive ears, and he spoke in the way that one tells a story to children:

“This was on a cold and snowy winter day. I travelled to one of the villages to buy a cow for slaughter. Upon my return at night I entered an inn that stood on the main road. In order to warm my bones, I took a quarter of spirit, and after a short rest I arose to continue on my way. The innkeeper approached me and whispered into my ear: it is not worth it right now to go out the road to get home, because the famous robber, whose name already escapes my memory, when out to the forest for his night's work.

I looked at him and did not answer. I went outside, I searched and I found a rock that was to my liking, elongated, comfortable to hold, and one end ended with a point. I threw it into the winter-wagon, sat, lashed the horse, and went out on the road. After an hour of travelling in the undergrowth of the forest, someone grabbed hold of the horse's rein and stopped it.

Stop! Give money and your blood will not be on your head!! I heard from within the darkness. I took the stone in my right hand, I got down from the wagon, approached him, gripped his fur lapels, got close to him so that I could see him, and hit him quickly on the head with the rock. He fell without emitting a sound from his mouth, and I continued on the journey. The next day I heard them telling in the butchers' shops that they found the robber killed in the forest and a rock was stuck in the top of his head.”

At the end of the First World War at the time of the outbreak of the struggle between the Bolsheviks and the Poles, he had already come close to heroism, and maybe above that. Among the Polish commanders was a well-known General by the name of Heller, whose soldiers were notorious as antisemites. One of their beloved pranks was to catch bearded Jews and cut the beards with a dagger. More than one or two had his beard removed along with the skin of his face.

On Kreiviyah Street on one of the mornings the “Medviedz” walked to pray Shacharit, with his tallit and tefillin under his arm. Two “Hellertzikim” clung to him and began to bother him and scream that they would cut off his beard. When one of them came near him to grab his beard, the old man caught him, lifted him up, threw him onto the ground like a twig, and yelled in his thin voice: “I will kill you [both].” The second pulled out the dagger and approached him, and in the blink of an eye the second one also already lay stretched out on the ground. By chance an officer riding on a horse happened by, the Commander of the Police. The two were shocked, did not dare to get up, and continued to lie there. The old man, being near-sighted, began to yell at the officer too “I will kill you if you come near me.” The officer calmed him, and said that he had come to save him. The old man calmed down, and continued on his way to the synagogue, as if nothing had occurred.

The Eccentric “Meir Yenkil Tarshinski” Known as “Penbook”

He always used to sit with his wife Raiza on a wooden beam that at some time had served as a butcher's block. After it went out of use they set it down next to the opening to the house and it served as a resting place towards evening between Mincha and Maariv.

Once when I was passing him at an hour that already approached the age of heroism, he looked at me and sighed deeply. “Why are you sighing Reb Meir Yenkil ?” I asked him. “Hah, my son!” He sighed again “I am getting older.” Yesterday I already felt the signs of old age. I went on foot to one of the villages to buy an animal and here after a walk of 21 kilometers I felt the need to sit and rest. Thus, thus, the powers get weaker and weaker.

In the days of the First World War, the time when the Germans first bombed from planes, a bomb struck Zundel the waggoner, may his memory be for a blessing, and cut off his leg. The panic in the city was great, for this was the first time that they felt it was possible to be killed by a person also from the sky.

I met Meir Yenkil on his walk from the market and he was carrying in the hem of his long coat a heavy set. I asked him “what happened in the market?” No emotion was showing on his face, as if it was normal to see airplanes every day. Quietly he answered me “You understand? Zundel the waggoner stood in the market and ate bread certainly without washing his hands. The “teitzlach”[1] came from above and took off one leg. I ask you, what is it their business if he fulfills the mitzvah of handwashing or not? What? Are they appointed over kashrut and the mitzvot by order of the Master of the Universe? They are heroes above, as a matter of fact, I would want to meet with them below on the earth, and then we would test our powers. They are heroes in the heights, psshh, a big stunt.

A Father and His Son – Zundel the Waggoner and His Father

The father was one of the Cantonists who served Nikolai the First for 25 years in the army. A quiet person, sad, perpetual grief was poured over his face, apparently that 25 years of his service in the army imprinted their stamp on all the days of his life. The son Zundel was taller than his father by a head and a half, ornamented with a white beard, much whiter than that of his father. Blue eyes as bright as a child's, always smiling, always walking behind his father like a calf behind a cow. Together they prayed, together they sat on the wagon, and together they ate. They never saw that one would eat without the other, and because of that “Zundel and his Father” became famous in the city.

[Page 198]

Reb Gershom the Shoemaker

He was a Jew at the age of seventy years or older, and the skin of his face was yellow like an old parchment, his beard was white, his eyes seemed to be always smiling, he knew very little about the doings of the great world. It was accepted that in the Shabbat Mincha prayer he would pass before the ark with the same niggun and the same voice for the course of twenty years.

Once on the first day of Pesach after the night of the Seder, he appeared in the shoemakers' Kloiz shaken and much paler than his perpetual paleness. With panic-stricken eyes he approached the basin, washed his hands, wiped them with the towel that was hung behind the bima, while whispering the “Asher Yatzar”[2] blessing. His mouth trembled and mumbled something about “Elijah the Prophet.” From his words it became clear that when his wife Temah went on the night of the Seder to open the door for “Pour Out Your Wrath” and when he announced “Blessed is the One Who Comes” there suddenly appeared in the doorway a figure of a person wrapped in lambskin above his head, approached the table, took the cup of “Elijah the Prophet” and emptied it at once, afterwards he emptied his own cup and also Temah's cup, and disappeared. With a trembling voice Reb Gershom continued: “we were so afraid that speech was taken from our mouths. When he took his cup I understood that he was Elijah the Prophet and recognized his cup, but when he emptied our cups I did not imagine that he would be a drunkard like that. The whole night I did not shut an eye, and even now I cannot calm down.” The worshippers calmed him down and told him that there was a sign of blessing in the matter and he should not think about it anymore. But members of the young generation knew whose antics these were.

In the neighborhood with Reb Gershom there lived a few Christian families, and members of these families were no less expert in the customs of the Jews than the Jews themselves. Among them was one non-Jew whose name was Mishka, and he was the hero of this prank. Afterwards Mishka regretted his deed, and he would tremble like a blowing leaf, for he was afraid lest the matter would become known to the authorities, and then he expected a severe punishment for insulting the religion, but the matter was hushed up and was very quickly forgotten.

Yaakov the Etcher (Yankele the Turner)

This was a person with a pale face, almost transparent, from his eyes were always seen fear and worry, which nested in him still from the beginning of his youth, when he learned the work of turnery. He worked in a workshop whose owner in the winter used to slaughter a calf or two and preserve the meat with garlic and all kinds of spices in a wooden barrel. The cold and the ice would freeze the meat which due to that would be suitable for eating all through the winter season. One time they slaughtered a calf, and hung its rear part in the vestibule, next to the exit, on a pole resembling a yoke, so that the meat would cool. Electricity in that period was not spoken of, one didn't yet hear about it, and in most of the houses of the poor they would use pieces of wood to light the house. On one of the evenings when he was preparing to go out of the house, Yenkil opened the door wide to go out; but the door that was opened flung the block of meat that was hung forward, and it swung back and struck Yenkil on the head with the closing of the door.

Complete darkness prevailed in the vestibule, so that Yenkil did not see a thing, he thought that someone was standing before him and struck him a blow. He immediately lifted his hand and stuck forcefully. By means of this the block of meat again moved forward, returned more quickly, and with a strong movement struck him another blow. Then Yenkil began to battle with his two hands against the unseen, and each time he felt that the concealed one made his blows more and more astounding without uttering a sound, while he, on the other hand, groaned with great pain. He decided in his soul that this is certainly a demon “Malachei'tzik,” and began to scream “gevalt![3] Hear Oh Israel!! A demon, a demon is here!”

All the neighbors that lived near the place came running, and lit up the dark vestibule with pieces of wood. What was revealed before their eyes? Yenkil lying fainted on the ground, and above him the block of meat hung on the pole, swaying.

Many years after Yenkil already had a family and took care of children, the joinery work was not enough to ensure his existence. Then he used to plant cucumbers in the summer on a plot of about two dunams. When the plants had only sprouted in his garden, he would put up a hut and sleep among his cucumbers. On moonlit nights he couldn't sleep and would pass from bed to bed in order to see how the cucumbers were growing. He believed that on nights of the moon the cucumbers grew. With affection and tenderness he would gather the cucumbers and organize them for sale. It was a pity for him to part from each cucumber, as if each one was a part of his body.

He did not get to make aliyah to Israel; he would become a symbol of the devoted farmer, and it is a pity that he did not get to do this…

Avigdor the Waggoner

He was a thickset Jew, he went about always with a ¾ length long cloak and high boots, beard white as snow, shorn nicely and neatly, cheeks ruddy as a child, a sharp, clever gaze as if to say: me you will not fool. When he fixed his eyes on a person his gaze penetrated completely. I met him in his eightieth year of life. He was very fond of children, he loved to gather them around himself and tell them stories, what he heard and what happened to him in his life. All the stories centered around one topic, how he travelled from Lida to Vienna in a wagon by way of Vilna, for in his time there was not yet a train. “Malachei'tzik,” a kind of demon, was always involved in his stories. I want to tell one of his stories:

Once on a dark night, he travelled in a dark and tangled forest, a cold and stormy wind really cut into the hands and ears like a knife. The sound of a bleating calf reached his ears. He got down off the wagon and here he saw a crouching calf in the middle of the road. He wanted to pick it up but it was beyond his strength. Finally he exerted himself and with toil and great effort he loaded it onto the wagon and went. After a few kilometers a wheel suddenly fell off the wagon. He got down off the wagon, with difficulty and great toil he reattached the wheel, for he was alone. Again he travelled a few kilometers and a second wheel came off. He was alarmed, got down and again affixed the wheel, but his heart pounded like the blows of a blacksmith on the anvil. Who know what was expected for him ahead? He was afraid to turn his head to look at the calf. Suddenly he heard a huge laugh rolling across the forest like thunder. He turns his head and sees that the calf has disappeared and is not there.

We children were very impressed by this story, and with the evening of the day we were afraid to go out of the house.

He married four or five times in his life. Once when he was going out of the rabbi's house with the new wife, their fingertips woven together, and hands swaying like the pendulum on a wall clock, I heard that he said to her: “Do you hear Tamar'eleh, if you will be good I promise you that I will always take from the daughters of your city…”

[Page 199]

Once, in the last year of the First World War, when he was walking from the Shacharit prayers, tallit and tefillin under his arm, he approached me and said: “Do you hear, child? When the Angel of Death will come to take my soul I will grab him by the throat and I will choke him, once and for all he will pass away from us.” He was then 85 years old. A short time after that I met him in the market when he was teetering on a wooden leg. I was afraid, because I didn't know about anything.

“What is this Reb Avigdor? What happened?” “It's like this, my boy, I got a wound in the leg and they cut it off me. You understand? I expected the Angel of Death to come from in front, but he the trickster stole up slowly from behind and caught me by the leg. Go wise up!” A short time after this he died.

The Star Gazer

His name I never knew. He always spoke in a whisper as if he counted each and every word. He is etched in my memory from the days of childhood: a tall Jew, like “Og the King of Bashan,”[4] a pale face, on his nose were a pair of eyeglasses for shortsightedness, he always carried a long coat upon himself, a pair of boots. His walk was always the same, whether he was hurrying or going slowly. Each and every step was a meter. His eyes were always lifted above, he was always sunken in thoughts, engaged with himself. On Friday before candle lighting he would walk along the storefronts to announce the coming of Shabbat. He would bang with a wooden hammer on the doors and from the massiveness of the knocking it was as if he was frightened and continued on.

On the two sides of the corridor of the great synagogue were two prayer houses for the Shacharit, Mincha and Maariv prayers. Evey week the worshippers there were porters, waggoners, and just bitter-hearted Jews who were engaged in the saying of Tehillim. There was not yet electric light; big tallow candles stood on a stand that was in front of the Shaliach Tzibur[5] and they lit up the whole house. The lights of the candles flickered all the time like a demon's dance, for the worshippers did not stand in one place but walked back and forth from end to end the whole time. The troubles were what accelerated them, and by means of this a wind was created. The shadows that were in the perpetual movement threw fear upon the small orphans who came to say “Kaddish” for the memories of their parents who died before their time and left them to groans.

In the first year of the First World War, between autumn and winter, before the evening prayer, the “Star Gazer” entered the prayer house. He washed his hands, and in saying “Asher Yatzar” murmured between sentences: “Who created the human” he broke a leg, “and created in him hollow body organs” he simply slipped from the horse “it is revealed and known before you” the English King.

Those who paid attention to his words thought his sense had departed from him. After two days when the newspapers arrived from Warsaw, the main headlines in the newspapers were: The English King George V fell from the horse at the time of a parade and broke a leg…

Until today it is not clear to me from whence and in what way the matter was known to him? And there was not yet radio in the world at that time for the use of the masses…

Translator's Footnotes:

by Mark Iliutovitz

Translated by Rabbi Molly Karp

Orphaned of parents and orphaned of family (a complete orphan). They knew to tell that at the time of the First World War he rolled into Lida with the wave of refugees. Who his parents were, who his relatives were, no one knew, and he himself did not know what to tell. He remained solitary, without a redeemer, on the streets of the city. Merciful Jews, children of the merciful, fed him, and in the end the holy congregation of the city of Lida accepted him. He was wretched, and in addition to that he was struck by fate. With one eye he did not see at all, and the second eye saw only with the help of thick glasses.

In his dress one recognized the coat of a Polish landlord, the jacket of some anonymous person, Berl's pants, Chaim's shoes, and Dovid's hat.

The stick, this was his personal property: a thick and strong stick. He didn't receive it from anyone, and he himself did not know how it reached him.

On the festivals he used to visit in the houses. The heart would shrink to see the orphan, who could not help himself. They did not stint, and they gave to him. And he, too, was not stingy. He blessed each one with an abundance of blessings.

On Purim he would sing his famous song:

Listen, Jew, listen, Jew,

today is Purim,

tomorrow is out,

give me a cup and throw me out.

Sometimes someone would dress him, suitably for Purim. His cheeks red, his lips with lipstick, a fine mustache, nu, and a beard – this was really a beard. It seems to me that he resembled “Santa Claus” more than a Purim player. Nevertheless – Moshe the orphan did not invest funds. This was the “presumption” of Yenta Pupke the haircutter, who was known for his extreme hygiene (before he shaved a customer he would wash his hands with soap and water). Moshe the orphan suffered a lot from unemployment. He was idle for days, months and years. They gave him donations, but not work. They simply did not believe that he was able to do something.

Once, on erev Rosh HaShanah, he turned to Mr. Yosef Iliutovitz, owner of a wine and beer factory, and requested work. He promised that he would do everything all right.

And indeed he approached the work with all seriousness. He took off his overcoat and hung it on a nail. Afterwards came the turn of the jacket, and finally he rolled up the sleeves of his shirt. He chose for himself in the yard a 500-liter barrel, rolled it, and stood it next to the pump. He connected a pipe to the pump, and its other end to the barrel. He checked the connections and after he was satisfied with everything, he approached the pump: he spit into the palms of his hands, an ancient act in labor, and began to work his muscles. The handle of the pump went up and down, and water began to stream plentifully into the barrel. Moshe had strength – “two horsepower,” if not three. The happiness was spread across his face: finally he has work.

He worked an hour, two hours, and almost didn't stop to relax. The factory owner approached to see how many barrels he had already filled. It became clear that even the first barrel had not finished.

“Boss, it seems to me that this is a magicians' barrel, I am already pumping a number of hours and the barrel has not yet filled.”

After checking, it became clear that Moshe forgot to close the barrel's spigot…

[Page 200]

by Yehudit Ganuzovitsch, of blessed memory

Translated by Phillip Frey

Already at age six Jewish children, both boys and girls were sent to kheder (elementary school, both literally and actually a room). It was custom with us , especially regarding boys, that the child was wrapped in his father's prayer shawl and brought to the melamed (teacher). One of those present used to throw a handful of coins over the child's head, all were wished mazl tov and the child was told that an angel was dropping them from heaven, and if he would study well they would always throw gold coins and that he would be successful in everything.

My first melamed was “Flashke”. I've forgotten his real name, but I remember his nickname well.

That nickname for a melamed had its flavor and reason, such that on a frosty day a Christian brought him a wagon-load of wood and forgot a flask on his porch. The melamed chased after him in his torn shoes running over the snow-covered street, without a coat, and holding the peasants flask he was yelling: “Flashko, flashko!”