|

|

|

[Page 373]

|

|

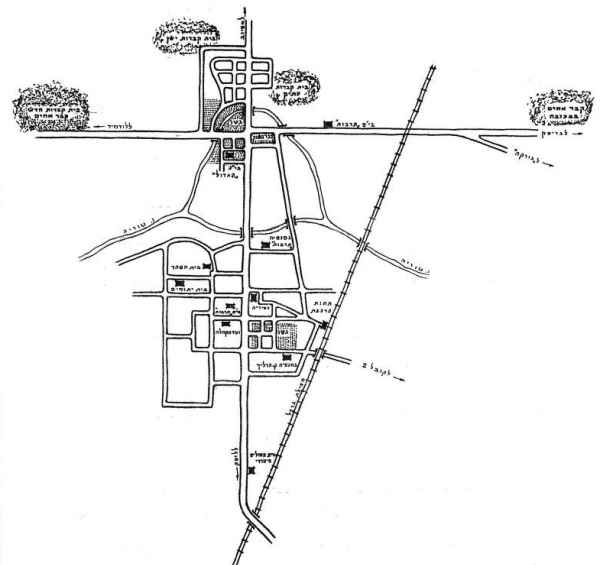

| A Sketch of the City of Kovel |

by Baruch Avivi

Translated by Ala Gamulka

My little hometown! How you enraptured me at all times, at all of my life stations, from childhood to this day?

I saw towns in Poland even more beautiful and larger, but you are most beautiful of all; I knew that there were long and wide streets in those other towns, tall and magnificent houses, blossoming gardens and shiny asphalt roads…

Your small streets, old wooden houses, stone covered roads and the sands in long trails are dearer to me.

I still see the narrow lanes snaking along the length and the breadth of the town, the wooden bridge connecting the “city” with the “sands”, the Turia River streaming slowly. In its clear waters can been seen bodies of many children. We are all children of dear Kovel.

With youthful tremor I remember the Great Synagogue, the Houses of Learning, the Shtiblach of the Stolin and Trisk Hassidim, the Rabbi's “courtyard”, the Hebrew primary schools and the High School– the pride of our town. They are all etched in my heart and I will never forget them.

Does the small house on Matseyev Street, built by my father, in good days, still stand? It was on the crossroads of four streets– Brisker, Trisker, Matseyever and Lutsker.

The many years that have passed have not dimmed your image. Every corner in town, from the beautiful train station to the distant “Gorky”– are all dear to me, then and now…

I was away from you, my hometown, in Vilna, Warsaw and Tel Aviv, but I never forgot you. I would return to you in my dreams and when awake.

How could I forget the good and innocent Jews, the dear children I educated to love Eretz Israel, my childhood friends who did not merit to reach the shores of our country?

I remember my last visit with great sorrow and pain. It was just before WWII. One could smell fires and fears grew of what would happen.

[Page 375]

My heart predicted evil events. Old men and youth walked as if they were shadows on the empty streets. One could detect great fear in their eyes.

The quick goodbyes in the train station where fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, relatives and friends stood close together. There were unpleasant –looking soldiers there, as well. I was offered hands for shaking and looks filled with love and blessings.

Suddenly, my late mother could be heard shouting: “Son, when will we meet again?”

She and the other people accompanying me did not know, neither did I, that this was our last meeting. We would never see each other again…

by Meir Ben–Michael

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Kovel, the city of my childhood, the city of my young dreams, was absorbed gradually in my memory.

Here the country road began that led from Lutsk, ascended up the hilly “viaduct” and descended to Lutska Street, ran through the comfortable life of the Jews and municipal hospitals; here was Cuperfein's oil press and here was Armarnik's mill – set out over Fabryczne, Koleyove and 3rd of May Streets [that] became smaller among the dozens of shops on both sides of the street and ended in its sandy part near the Turya [River], dropped into the city across the bridge, meandered farther through Warszawer Street, diverged in Ludmirer [Street] where the Kovel Jews would be led to their eternal rest, turned onto Brisker [Street], faraway to Gorki and disappeared in the distant gardens and orchards of Maciever [Street].

[Page 376]

Here were your residents, several small industrialists, more merchants, [people from] various professions – doctors, lawyers, teachers, technicians, hundreds and thousands of retailers, artisans, workers, dear Jews who toiled all year long.

Kovel of the struggle for an income, for daily bread; in a fight with Polish anti–Semitism, of the limits of a precarious economic situation.

The city of merchants' associations, of retailers' unions, of artisans' associations, of a people's bank, of a merchants' bank, of the interest–free loan fund; of widespread social work that itself supported dozens of organizations and institutions like an experienced state system:

Of Linas haTzedak [society for the homeless], where poor Jews received help from doctors and the necessary medicines without cost; of Beis Yesoymim [home for orphans], where small babies were raised; of Moyshev Skeynim [old–age home], where the old people lived out their lives in dignity; of Bikur Khoylim [society to provide lodging for the needy and visitors to the sick], of the Jewish hospital, of Hakhnoses Kale [society to assist poor brides], of Gemiles Khesed [interest free loan society], of Maos Khitim [help for the poor to celebrate Passover];

Of the ORT [Obschestvo Remeslenovo i. Zemledelcheskovo Trouda – Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor] school where young girls learned a trade; of TOZ [Towarzystwo Ochrony Zdrowia Ludności Żydowskiej – Society for Safeguarding the Health of the Jewish Population] and its summer residences where hundreds of malnourished Jewish children were healed in fresh air.

The city of diverse educational systems, in which all communal [political and religious] leanings were reflected:

Of the first kindergartens, of the increased number of public schools, of the Herzlia and Dr. Klumel school; of the Tarbut gymnazie [secular Zionist secondary school] and of the Polish–Jewish middle school; of the [elementary] school of Tsysho [Central Yiddish School Organization – secular socialist Yiddish schools]; of the large Talmud Torah [free school for poor boys], of the dozens of khederim [small religious elementary schoolrooms], of the Yeshivus [religious secondary schools];

Of People's Libraries, of Hebrew reading rooms, of the leftist Peretz Library, of literary courses and evening courses, of the dramatic societies, of the theater rehearsals of Khalat and Tarn;

[Page 377]

the choir, of the very talented Kalmen Lis' songs celebrating Volhynia; of Asher Frankfort, the untiring fighter for Hebrew culture; of the weekly newspapers; of the Tanakh [Torah, Prophets and Writings] circles and the Torah Society, where overworked Jews would find relief [studying] a page of the Gemara [Talmudic commentaries].

The city of pious Jews, of the Trisker [rebbe's] court, of the large synagogue, of Pruszanski's house of prayer and the Komerczeske synagogue at the Zamd [the Sands – the newer part of Kovel]. Of the shtiblekh [one–room synagogues for specific groups such as Hasidic sects or occupations]: Trisker, Lubavitcher, Ruzhyner, Stepaner, Neshchizer; of Reb Welwele, of the old Grabowicer, of Nukhem–Moshele, of Efroim the religious judge, of Rabbi Lanke, of the heads of the yeshivus [secondary religious schools], of the Jewish melamdim [religious school teachers], of Reb Shmuelik Goldberg, of Yosl the melamed [teacher], of Reb Motle, of Reb Pinkhas, of Fidta and of Reb Nisl Farber.

The city of the Jewish civic club, of the Zionist community center, of the illegal meetings, of the communist youth;

Of the political effervescent life; of the widespread Zionist movement: of Et Livnot [This is the time to build], El Hashomer [On the Guard], Mizrakhi [religious Zionists], Hitakhdut [Zioinist Socialists], Revisionists, Poalei–Zion [labor Zionists], Hahalutz [Pioneers], Hashomer Hatzair [Young Guard – Socialist Zionist youth movement], Tzairi Mizrakhi [Mizrakhi Youth], Betar, Hahalutz Hatzair [Young Pioneers], Freiheit [Freedom].

The city of the first strikes, where the worker activist, Pesakh Szpringer, was led to jail in chains.

The city of Jewish folksiness, of Pesya the katshkes [raiser of ducks], Chava the pipkes [tobacco pipe], of “beautiful women,” of the “tall Jewish woman,” of Yosl the water–carrier, who sold simple water from the Turya [River], and “Warsaw” water [water from Warsaw] from the pump on Listopadower Street and which in Soviet Kovel immediately began to sell “Moscow” water; of Khil with his eternal yoke on his shoulders – “Well then, Khil, what day did the second day of Rosh Hashanah fall 10 years ago,” – the city of the thin, stuttering Hershele with the typical appearance of a recluse – a goo–ood, a goo–ood, good night –.

The city of the dear young Jews. Apprentices, employees, workers, of the Turya [River], in your water the young

[Page 378]

girls and men learned to swim, you did not move, lay a fathom deep; of Lag B'Omer [holiday usually occurring in May celebrated with excursions and bonfires] excursions, where hundreds and hundreds of young people walked through the streets with white and blue flags and spent the day in the surrounding woods; of the First of May demonstrations, where the young demonstrated their wishes for a better life, of the young sports organizations, Makabi, Hashmonai, Bar Kokhba, Krima with its football–gymnastics and other divisions.

The city of the youth circles for Yiddish literature, Jewish history; of Ohel Shem, where Hasidic young people in their last year at the middle school drew spiritual nourishment from the ancient wells; how hundreds of young people would disappear in the evening at the premises of Hahalutz and Hashomer Hatzair as well as Betar, Tzairi Mizrakhi and the Peretz Library.

And here, my small section of Lutsker Street, from Kaliyeva to Krulova Bane. On a summer night under the starry heaven, or in the frosty, dry winter evening, the Kovel young people occupied its kingdom. They strolled, taking up the entire width of the sidewalk. It was crowded, narrow, friendly. Here, one heard Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, Russian. They spoke about the synagogue, about work, about politics, about love, about serious things. They bickered, they discussed. The air became full of a song, vigorous noise. Sometimes a couple separated, went apart [from the others], moved aside. The first innocent declarations of love were heard by the trees on Monopoliove Street and from Vulka [Street].

The city of the last years, just before the Second World War. Difficult economic conditions, intensified anti–Semitism, the hopeless situation of the majority of the young Jews, Kovel and the devil at the entry of the German beasts.

Kovel in the days of the Polish–Russian War – how you grew overnight, my city, how at once your streets became wide, thousands and thousands of Jewish

[Page 379]

refugees from deep in Poland flowed ceaselessly through them, escaping from the Nazi troops.

How you accepted [the refugees] so fraternally, my home. Your Jews [accepted] them into your homes, gave them a place to sleep, brought them a meal, warmed them with words of consolation.

And thus, almost doubled [in size], you welcomed the Red Army, which brought them salvation from the Hitler beast.

Kovel in the years 1939–1941, the period of adapting to a new life, an economy built on a new foundation, total changes in the social–communal life.

Kovel in anxiety because of the new Hitler victories. The Soviet military went through the empty street toward the border. The 22nd of June 1941. The city was awakened by the first German bombs. War. The Trisker Rebbe blessed the Soviet tanks on Brisker Street.

The German troops entered your streets with force, Kovel, my city. The wild blood–thirsty beast already held you with its nails, my city.

– Escape, my brothers, hide, save your babies! –

Amalek had come again. Wild German murderers, wild blood–suckers, boundless bandits ruled over you and with them the Ukrainian murderers, your neighbors for 100 years, they defiled you, killed your children, drove them to work, looted Jewish possessions, locked [the Jews] in the ghetto, set their [annihilation] as their goal.

Kovel of the march of the martyrs. They drove your starved and defiled children through your streets, here at the Brisker highway, here in the village of Bachuv, here they had them undress, stood them near the prepared pits, here the volleys were heard. One after the other, dozens, hundreds, thousands fell. An entire city perished al Kiddush haShem [as martyrs]. The German murderers shot, the wild Ukrainian supplemented them with pitchforks.

[Page 380]

Kovel with its large synagogue that remained as a remembrance after the Holocaust, where many of the tortured Jews wrote their last words on its walls with their blood.

Kovel with its only large mass grave near Bachuv where, immediately after the war, the dear hands of several of your devoted children fenced in and erected a wooden matzevah [headstone].

But Kovel, my city, you have not yet perished.

Among the many millions [of people] in New York, in noisy Paris, in Buenos Aires and in distant Australia, you still live, my home. At memorial evenings, in a yahrzeit [memorial] candle, in a deep moan, in memories that are handed down to children, Kovel, my city, you continue to come into our memories.

More than anywhere, you live in Israel, where your children are building a home for themselves; where they will be able to live without terror or fear, as free, proud people and Jews.

You Live Forever, Kovel, My City

Footnote

[Page 381]

by Dr. Y. Glicksman

Translated by Sara Mages

The journey to Kovel in those days - October 1939 - wasn't the easiest thing to do.

In theory, there was a rail service. But in reality, no one knew when the train would leave. Those who wished to travel - walked slowly to the train station and waited for several hours. Sometimes they waited for a day and sometimes - for an entire day. Rovno's train station - as in other cities that were occupied by the Soviet army - was besieged, day and night, by thousands of people. Masses of people lay on the filthy floor of the train station and shivered with cold.

It was a large population of refugees, most of them Jews, who were uprooted from their homes and wandered from place to place. They, their children and their wives, couldn't find a place to rest in. No one cared for them. The hunger sucked the marrow of their bones and diseases spread

Finally I got to enter the train car. The train drags itself from Rovno to Kovel for 14 hours instead of two hours in normal times. The glass windows are broken, and despite the crowds and the congestion it is bitterly cold in the car. The car isn't lit at night and we're immersed in darkness.

Here our feet are stepping on Kovel's soil. The NKVD (the former G.P.U) seized the most magnificent building in Kovel. It wasn't easy to enter this building, and it was especially difficult to get an audience with the city's officer. Various officials interrogated me for the purpose of my visit.

The next day, at dawn, I reported by the prison's gate with a food parcel for Victor Alter. I saw a long line of mournful sobbing women. These were the wives, sisters, and old mother of Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian prisoners.

[Page 382]

All of them held baskets and packages and waited, in the cold and in the rain, for the time of “delivery.”

I was lucky that I came on “delivery” day. However, the people who stood at the prison's gate told me that there was no assurance in the matter. Sometimes, after many hours of standing in line, they scatter those who wait and don't accept their packages.

At times - so I was told by the waiting women - they do accept the package, but a shortly after the prison guard returns it to inform you that the prisoner was not there.

Then, terrible thoughts start to haunt you: maybe the prisoner is dead? It's being told in the city that night after night corpses are taken out secretly from the prison. However, it's possible, that they “just” took the prisoner to another prison. Or, maybe they sent him to a concentration camp? Who knows? The family will never know.

Very quickly I tasted the flavor of the Soviet prison in Kovel. It was a small empty room in the basement of the NKVD building. It was bitterly cold in this dungeon. For two days I lay on the cold floor in a state of semi-consciousness. I couldn't sleep in the cell because a light bulb, which was lit day and night, was hanging over my head. The light bulb was strong, about 250-300 watt, and blinded my eyes. The bright light stabbed my eyes and caused them great pain. I felt like they placed me next to a spotlight.

The only window in the cell was covered with a thick screen, and a beam of light painfully penetrated inside. Therefore, I wasn't able to distinguish between day and night.

I wasn't given food for two consecutive days, and furthermore, I wasn't even given a drop of water to wet my throat or wash my hands. No one was interested in my fate. No one asked me for my wish. Dead silence reined around.

On the third night, at dawn, an NKVD officer entered the cell and started to scream: Pack your bags! Get dressed fast!

He took me out. It was four o'clock in the morning. At that time the police was very active in Kovel. The streets were still as if life was taken from them. Six soldiers armed with rifles that their bayonets pointed upwards surrounded me.

Finally we arrived to the prison. They put me on the third floor in room number 33. It was a very large room, intended for several dozen prisoners. However, I was in it alone. All the glass windows were broken and the winds raged in the room undisturbed.

To my delight, there were a few crumbled and worn strew mattresses in the room. The lightest touch

[Page 383]

raised plumes of dust. The mattresses were very dirty and full of fleas. I made a “king's bed” from these mattresses.

In spite of that I couldn't undress because the cold was unbearable and ate my bones. Rain and snow blew through the windows.

I must comment that the regime that prevailed in the Soviet prison in Kovel wasn't typical to Soviet prisons in other locations. The regime was much more severe in other Soviet prisons.

Translator's Note

An important consultation of Jewish and Polish socialist's leaders was held in Kovel a few days after the city was occupied by the Soviets. A memorandum, which was written in this meeting, was given to the Soviet mayor. A wave of arrests came in response to the memorandum. Alter was arrested on 26 September, 1939.

Dr. Y. Glicksman, the brother of Victor Alter, describes his journey to Kovel to visit his brother who was incarcerated in the Soviet prison in Kovel. His words, which are given with a few omissions, were taken from the book “Henrik Ehrlich and Victor Alter,” which was published in 1951 by “Unzer tsayt,” New York. Return

by Yaacov Kobrinski

Translated by Sara Mages

The school year 1940-41 in the “Vocational High School No. 3.” This school replaced the school named after Dr. Klumel, and its language of instruction was Yiddish. We - I, who was given the task to continue as the school's principal, and the teachers: Genia Liar, Ester Pomerantz-Shalita, Baruch Toyeb and Aharon Rosenstein of blessed memory, and may he live long, Yakov Shalita, who lives with us in Israel - were a group of modern “Anusim” [1] within the walls of this school. The rest of the teachers were new, “party” members, and despite the fact they were good honest people and were friendly to us - there was an atmosphere of “keep your tongue.” It was better to be quiet about the recent past. Besides that, we were sure that special duties were also given to a number of students from the higher classes and to a number of parents - and this required us to be very careful and caused alienation.

And here, two weeks before Yom Kippur 5702 [1941], the superintendent, Moshe Tabachnik, appeared at our school every day. He was very interested to know, if we properly managed the propaganda that the students should come to school on Yom Kippur (on Saturdays the studies were like in other schools). He also hinted that it will be a test to the teachers' educational skills… I felt, that the students were excited and confused, and waited for an unofficial hint from me. We knew well the feelings of the others without saying a word. Two days before the holy day, I released myself from my administrative duties, and participated in the games during the big break. Between the games and the small talk about this and that, the student received a hint that they should come to school, but they won't be forced to write or eat. My dear holy sheep didn't fail me. The teachers stood the test, and the lessons were designed so there was no need to write. But, there's no rule without exception. Rabbi Moshe Teverski zt”l came to my house a few days before Yom Kippur and asked me with tears: “How is

[Page 384]

it possible that my son, a fifth grade student, will desecrate the sanctity of the day?” And my advice was: “As of today your son is sick with dysentery, and I promise him a certificate of illness from the school's doctor for a week.”

Etched in my memory is the graduation party on Saturday night 14 June, 1941. We sat at a social gathering, the lovely and pleasant - the students of the sixth and seventh grades with their parents, delegates from other classes, and almost every faculty member. There were, of course, also representatives of the authorities who gave routine speeches. A seventh grader blessed in moving words, and handed me the class' gift - an elegant volume of Shalom Aleichem's children stories, which was published in Yiddish by the Soviets in Kiev.

My turn came to speak. In this occasion I didn't want to appear before my acquaintances and friends from the past with routine words. On the other hand, I wasn't allowed to appear before my superiors as “political unconscious.” Therefore, after a few heartfelt words about our life together at school, I said that we need to be grateful to the regime, the person who represents it, and the precious treasure that he had given us - peace! “Put before your eyes what's happening across the border, just 50 kilometres from here, and you'll understand how lucky we are!”

I confess: that at that time my mouth and my heart weren't a hundred percent equal, because I was very worried about the future. What we feared the most, come to us, the dreadful journey eastward of the German soldiers, may their names be blotted, started exactly seven days after this party. Except for half a dozen, or maybe up to ten of those who attended that party - no one survived.

May their souls be bound in the bond of everlasting life.

Translator's Note

by Yehoshua Frankfurt

Translated by Sara Mages

The Soviet occupation brought a big change in the Jewish street in Kovel. It wasn't the character that was known to us from the years before the war. There was an atmosphere of depression. Many Jews were forced to close their stores and their workshops, and sat, almost, idle.

The new regime brought in its wake a total change of values. People moved about gloomy and anxious, wondering and looking forward. They knew that they had to look for new sources of income, but they weren't ready for it in any way, especially, mentally.

However, this wasn't the only change that took place in the Jewish street. It wasn't the economic

[Page 385]

insecurity that burdened the hearts of our brothers in the city. What depressed their spirits the most was the political insecurity and the denial of freedom of speech.

The new regime, and with it the first wave of arrests, quickly made it clear that it was necessary to learn the theory of silence. They had to remove from their talks on current events many topics that were close to their hearts. And the most important thing: they could no longer trust their “closest friends,” because, this time, the words of our prophet: “Those who destroy you and those who lay you waste shall go forth from you…” were fulfilled. There were informers, who, for so called “ideological reasons,” saw themselves as emissaries, and brought words of slander to the attention of the new rulers.

The voice of most of the Jewish community fell silent. The public life, which pulsed in various forms, has been paralyzed. Most of the Jewish youth, who was educated in the national spirit either in the network of Hebrew schools or in the Zionist youth movements, was sentenced to a double decree: On one hand they weren't allowed to speak Hebrew and had to break away from the realization of the Zionist vision, and on the other hand, they had to recognize Yiddish as their national language, and to integrate into a new way of life, which was foreign to their spirit and belief. This youth wandered gloomy and disappointed.

It should be noted, that not everyone accepted the new situation. There were those who met secretly to refresh their Hebrew and talk about forgotten times, and there were also those who weren't satisfied with these secret meetings. They left their homes and fled through unknown roads to Lita and Romania, in order to emigrate from there to Israel.

This was, in general terms, the face of the Jewish street at the end of 1939. At that time, the Soviet authorities decided to include the local population in the elections to the “Supreme Soviet.” The Soviets decided - as it became clear later - to try to pull to their side the most important local people, famous people, that their influence was also known outside their place of residence.

The goal was twofold: First, to prove to the outside world that the residents of “Western Ukraine” saw the Soviets as “liberators” not “invaders.” Second, to show the local residents, that even their former leaders support and cooperate with the new regime. They also had another trend: to show, that the Soviet regime wasn't only based on communists, but also by people who had other views in the past, people, who officially ceased their affiliation with their former political party, and now are called “nonpartisan.”

As fate would have it, the choice in Kovel fell on Asher Frankfurt z”l. For some reasons, the Soviet authorities decided that he was the suitable man for the “Supreme Soviet.”

The story began in the deepest secrecy. One night, some time before the preparations for the elections, a man dressed in the NKVD [1] uniform appeared at Asher Frankfurt's home at midnight, and invited him to join him.

[Page 386]

It's easy to imagine the reaction of Frankfurt and his family members. They stood frightened and alarmed, and asked the “man in uniform” what he had to take for the road. Are they arresting him, does he have a warrant for his arrest or for the entire family, etc…However, they failed to get a hint from him about the purpose of his visit. His only answer was: I was ordered to bring you to a certain place, and that's all. When Frankfurt z”l asked to take a bundle of cloths with him, the “man in uniform” said that they should hurry and there's no need to take anything.

A small elegant Soviet style passenger car, one of the few that appeared in the city at that time, was waiting outside. Later we found out that the car belonged to the secretary of the Communist Party in the region.

The car stopped next to the NKVD building. Frankfurt z”l was brought to a room in which three people sat. Of them, only one was known to him personally. He was the secretary of the local Communist Party. His wife served as a “politruk” [political commissar] in the United Jewish High School.

Frankfurt z“l was surprise that the reception was somewhat warm. The officials' serious “tone” disappeared immediately, and he was invited to sit with a kind smile. They asked for his forgiveness that they troubled him at night. Tell us about yourself - one of them turned to him. “What I should tell you?” asked Frankfurt z”l. They answered: “Tell us the story of your life.” Amazed and full of hesitation Frankfurt started to tell them the story of his life. After the first few sentences, one of the men remarked, that even the “high ranking officials” in Moscow would be proud of his pure Russian. Indeed, this wasn't an exaggerated compliment, since in addition to his religious education he was also educated on the knees of the Russian culture, and he spoke this language during his many years of studies in Kiev and Odessa.

His story lasted for two hours, and before he finished the three men rose to their feet and thanked him for his words. They immediately informed him that he would be invited to another meeting, but he shouldn't tell anyone about this meeting.

The reason for this meeting hadn't been told to him, and when he saw that the meeting was shrouded in secrecy, he realized that he had to be patient, and wait until they reveled its meaning to him.

The elegant car was waiting outside. To Frankfurt's surprise, the “man in uniform” saluted him, opened the car door, and invited him to enter. The family was happy that he was brought back home.

The next day he went to his work as a school principal. At that time the authorities consolidated the two Jewish high schools the city - the Hebrew High School and

[Page 387]

Klara Erlich's high school - into one high school whose teaching language was Yiddish. As stated, Asher Frankfurt z”l was nominated as the principal of the united high school, and Mrs. Klara Erlich was appointed as his deputy. In theory, this was the official management, but in fact, the decisive opinion on fundamental issues was given to the “politruk,” the wife of the secretary of Communist Party in the city. Officially, her role at school was to guide in matters of sports and military training, and she also organized the activities of the Komsonol [2] among the high school students. In fact, the “politruk” acted as the institution's “mistress.” Her attitude to the teachers and the management was the attitude of a master towards his servants. She tried to emphasize her power, loved to explain the basics of the Soviet education, and the primacy of the Soviet educational methods.

The morning after the mysterious meeting, the “politruk” welcomed Frankfurt z”l as before. She didn't give him a clue, even though she knew something. However, there was a high degree of respect in her attitude towards him. Suddenly, she began to listen seriously to his words, to answer with Amen to each word that he had spoken, and consulted with him about the arrangements that she was going to regulate. And lo and behold: previously, she served as a consultant and master - suddenly, she became docile and was willing to take advice and guidance.

Several days later, in the middle of the night, there was another knock on Frankfurt's door. The “man in uniform” appeared, and in a faint voice invited him to come with him. Again, he was brought to the NKVD building. The same “trio” sat and asked him to continue his story. He was asked a few questions, mainly about his past activities. It was difficult for him to distinguish the responses to his answers, because the light in the room was directed at him, while the three men, who sat across the table, were almost immersed in the shade.

Two hours later, they stood up, thanked him for his story, reminded him to maintain the confidentiality of the meeting, and that he would be invited for the third time.

In those days, the attitude of the “politruk” towards the principal improved. It became more dignified and more flattering. She started to show interest in his health, was worried about his comfort, and reacted badly when he was interrupted. She arrived to school early, greeted him with a smile, and left the building only after he left. The tension in Frankfurt's heart increased. In addition to the “trio” other people, who usually didn't present themselves, also attended the next meetings. Their faces weren't familiar to Frankfurt z”l, and made an impression that they were men of power from elsewhere. Frankfurt z”l was forced to retell his life story a number of times. At the end of his words he was asked a several questions, they praised him and parted from him.

In one of these meetings they questioned him at length with two questions: The first -

[Page 388]

why he founded the Hebrew High School, and the second - under what circumstances did he make the agreement with the Ukrainian minority in the region before the elections to the Polish Siejm [3]. There was a hint in it to the well known case in the Polish Jewry about the “Minority Treaty,” which was arranged by Yitzhak Gruenbaum. Its aim, among others, was to increase the number of minority delegates in the Polish Siejm.

Asher Frankfurt z”l conducted the negotiations with the Ukrainians in the Wolyn district. He was known to the Ukrainians as one of the opponents of the Polish regime, and the Polish desire to dominate Wolyn. This point was extremely important for the “trio.” They dwelled upon it many times, and kept on asking him if it was true that he didn't approve the Polish regime in Wolyn. In addition to that, they showed an “understanding” for his answer about the founding of the Hebrew High School. His explanation was that as a national Jew, he saw the need to establish a Hebrew High School which will educate the young generation in the national spirit, train it for his immigration to Israel, and prevent its assimilation. Later also told them, that despite difficulties and obstacles that the Polish authorities set up, he continued to struggle for the existence of the Hebrew High School. He didn't give up even when his school wasn't given state rights, when at the same time, the second high school in the city, that its language of instruction was Polish, received these rights.

Frankfurt's story, on how at one time, before the elections to the Siejm, he was offered to place his candidacy in the B.B.W.R [4] list, the Sanation's [5] list under the leadership of Colonel Koc, the assistant and advisor of Marshal Rydz-Śmigły, in order to attract Jewish votes in favor of the ruling party. He was promised that in addition to providing a place in the Polish Siejm, he will receive rights and recognition for the high school, or the post of the director of the government's high school in the city whose director was Mr. Gura.

However, he had been told explicitly, that if he didn't agree to the proposal, the high school will be closed, or he would be dismissed from his post as director.

In response to his refusal to support the“Sanation,” Frankfurt z”l was suspended from his position as the school's principal for a period of time. He was forced to pass a test in the Polish language at the University of Vilna. He was reconfirmed by the authorities as the school's principal only under the pressure of various public factors.

These words found an attentive ear and were accepted by the Soviet “interviewers.”

One night Asher Frankfurt z”l was called again to the secret meeting, and in the presence of a number people (among them the regional Communist Party secretary, and a representative of the government from Kiev), he was told that it was decided to present his candidacy for the upcoming elections to the “Supreme Soviet,” meaning, as a candidate of the “nonpartisan” who was recommended by the Communist Party.

[Page 389]

He doesn't need to deny his past affiliation with the Zionist organization, but, he should declare in public meetings that he sees the Soviet regime and the Soviet system of government, the right solution for the nations of the Soviet Union, including the Jewish nation. Frankfurt z”l tried to say, that the matter wouldn't be well received because he's known by many as an ardent Zionist. Also, personally, he doesn't find himself worthy and suited for this supreme notable job. The answer to his words was short and sharp: comrade, your candidacy has been approved by Comrade Khrushchev (at that time, Khrushchev served as the secretary of the Communist Party in Ukraine, and was its leader).

The answer blocked the way to all sorts of questions and additional inquiries. To the amazement of those present, Frankfurt z”l asked to give him time to think about his answer. They couldn't understand how a man dares to ponder a decision from high above. He promised to give his answer on the next day.

The next meeting was attended by the “trio” and the representative from Kiev. Again, Frankfurt pleaded before them that the public wouldn't approve it, and besides that, his frail health prevents him from accepting this honorable and responsible role. Their answer was that the matter has been decided and it was impossible to change it. The meetings of the “Supreme Soviet” are being held twice a year, and a special rail car will be made available to transfer him and his family to Moscow for the meetings. Also, he will not have to worry about the school. A special office will be arranged for him in the city, and he will receive representatives from the entire region during a few office hours. He was promised that they'll take care of his needs, and it won't be difficult to fulfill all of his wishes in regards to his duties.

From now, everyone started to treat him with great respect. He was invited to parties with representatives who came from other locations. “Visitors,” accompanied by the local “party” secretary, came to the high school to meet Frankfurt z”l. They treated him with politeness, whereas the local “party” secretary and his wife, the “politruk,” literally worshiped him.

At that time, the Soviet authorities started to hold preliminary meetings in the workplaces to select the candidates for the “Supreme Soviet.” In one day, meetings were held in the railway workers chamber and in the liberal professions (teachers, clerks etc.) chamber. The meeting of the railway workers went well. Frankfurt's candidacy was presented by the chairman (a member of the Communist Party from the outside). He read Frankfurt's biography without mentioning, even in one word, his Zionists activities. He praised Frankfurt's resistance and struggle against the Polish government and his good relation and close ties with the Ukrainian people.

It wasn't the same at the meeting of the intelligentsia. This meeting was turbulent.

[Page 390]

The chairman of the meeting was shocked when panic broke out in the hall when he announced, on behalf of the Communist Party, his support for the candidacy of Frankfurt z”l.

Many of the Jewish and Ukrainian communists in the city participated in this meeting. During the Polish rule, they were political prisoners for many years, and couldn't accept the fact that the Communist Party will present the candidacy of an ardent Zionist to the “Supreme Soviet,” even on the behalf of the “nonpartisan”.

Veteran communists came on the stage - to the chairman's embarrassment - and expressed their vigorous opposition to the proposed candidate. However, there were also those (surely few in number) who immediately understood the situation, and started to praise the candidate and found him fit.

Suddenly, a former political prisoner got up and opened his statement on behalf of his friends, the political prisoners. While he was talking, the chairman emitted the following sentence: “You claim that you appear on behalf of a group of communists, however, we don't know, yet, what kind of communists you are.” It was a meaningful warning.

During his speech, the speaker called in the direction of Frankfurt z”l, who was sitting on the stage next to the chairman, to declare in public whether he completely renounce his Zionist past, and sees a grave mistake in his political views in the past.

Frankfurt interjected and replied immediately, that he doesn't deny his past activities, and he's not willing to see them as a mistake.

Panic rose again in the hall. The chairman, who wasn't ready for such a sequence of events, loudly announced the postponement of the meeting.

Intensive debates started in the government circles. One day, Frankfurt z”l was rushed (this time it was during the day and not at night) to the secretary's office who informed him, that the Communist Party reevaluated the situation, decided to grant his request, and will not present his candidacy to the “Supreme Soviet.” From then on, he could continue to serve as the principal of the Jewish High School.

A heavy stone was lifted from Frankfurt's heart. He remained in his position until the Nazi invasion. It's interesting to note, that with the outbreak of the war with the Germans, the Soviets offered Frankfurt z”l to leave the city in a special train that was intended to evacuate the government institutions in the city and the region.

Frankfurt z”l didn't accept the offer because of his poor health (he suffered from angina pectoris), but he advised everyone he knew to leave the city and not to stay with the Germans.

Translator's Notes

[Page 391]

by Monia Galperin

Translated by Sara Mages

For a certain period the city was in a state of interregnum – between two successive regimes. There was no rule in Kovel. The Polish Army was destroyed, defeated, the fighting subsided and it was quiet on the war front. In the race between Germany and Russia we didn't know which of them will enter the city first. Those, who saw in their astrology that the Germans might enter the city, were horrified. They packed their belongings and got ready to escape to Russia.

A day or two later, a squadron of planes appeared in the city's skies, and when they flew low we clearly saw that they were Soviet planes. A wave of joy passed over the city's Jews, but our joy wasn't complete because the Germans were already in Luboml.

At four in the afternoon we received a notice that we've nothing to fear because the Soviet tanks will arrive to the city's gates within a few hours. There was no end to our joy. Many of the city's youth left for Hulova to welcome the Soviet Army. The first tanks, on which our youth sat and sang with joy, arrived to the city at five in the afternoon.

The Russians came from the direction of Lutsk. Trucks, full of Russian soldiers, traveled on both sides of the road from the viaduct on Lutska Street to Brisk Street. The city's Jews welcomed the soldiers of the Red Army with enthusiasm that is hard to describe in words. The city rejoiced all night.

The first act of the Red Army was the opening of the prisons. Political and criminal prisoners were released. The political prisoners, who were arrested for the crime of Communism, took the power in their hands. We saw then a strange picture – office managers sat in their offices in prison uniform because they haven't had the time to prepare their official uniform. Many of Kovel's Jews, who sat in jail during the Polish period because of their affiliation with the Communist Party – enlisted to the police after their release.

In the early days the administration was very flawed and the city greatly suffered from lack of sources of income. However, the situation slowly improved and all the healthy men and women were called to work. The professionals were given jobs in the cooperatives and the non–professionals were given jobs in various offices. Each had to identify himself with a work card. Those who didn't have this card – were given the evil eye.

A short time later the Soviet authorities gave an order that everyone must be counted and get a Soviet identity card. The city's Jews received the order willingly and reported to the census in an organized manner.

[Page 392]

At that time there were many refugees from Poland in the city who didn't want to get a Soviet citizenship. The authorities let them be and didn't take revenge on them.

Half a year later, notices were posted in the city that those, who want to return to Poland, need to register in a specific location and special railcars will take them to their place of residence.

At that time, a rumor spread in the city that the Jews who live on the German side of Poland, especially in Lublin, engage in various businesses and live well. For that reason many of the Jewish refugees registered for the departure from the city because, as we know, the Russians banned trade.

At the end of the census the Russians collected, in one night, all the trucks in the city. They came to the homes of those who participated in the census, put them in the trucks and sent them by train to Russia.

Life went on in the city until 1941. One Saturday night, when all of us were in the cinema, we were shocked by the news that a war broke out between Russia and Germany. On Monday morning the city, and the surrounding area, were bombed. It was the real proof that war broke out even though all of us believed that it would happen later.

Most of the young men were recruited to the Red Army. The Soviets placed a train with a lot of cars in the train station to transport the residents to Russia. Many filled the cars and waited for the engine to arrive. But two days later, when the long–awaited engine didn't arrive, the Germans bombed the train, the train station and the city itself. Many lost their patience and returned to the city, but those, who had strong nerves and stayed on the train, were rewarded with an engine who took them to the interior of Russia and thanks to that they survived.

I was recruited to the Soviet Army and worked, with others from Kovel, as an electrician in Gorki. The German bombardment intensified from day to day and Gorki was also bombed. We realized that we were in great danger and decided to escape from the city in a car. We arrived to Kamen–Kashirskiy, from there to Sarna and advanced eastward. The road was difficult and dangerous and we were bombed all the time until we arrived to Poltava.

In Poltava an order caught up with us that those, who came from the Ukraine, would be release from the Red Army and must proceed on foot to the depths of Russia.

And so began the terrible days of wanderings, without a home, without a shelter, without heat, without food and water. The front line wasn't known to us and when we arrived to Pirtin we were captured by the German. The Toker brothers, Eli Schnitzer, Petkovsky and others, whose name I don't remember, were captured with me.

The Germans sorted us out and separated us from the non–Jews. The barbarians undressed us, took our clothes and gave us rags to wear. They took our shoes and we walked barefooted.

[Page 393]

The prisoner camp contained about 15.000 men. There was only one well and we had to stand in line all day to get a glass of water. The non–Jews received flour and potatoes every other day. The Jews didn't even get that. The Germans, who advanced to the front, looked at us as strange creatures because they were sure that a single Jew wasn't left in the world. The situation was uncontrollable. Each of them abused us and beat the living daylights out of us with their rifle butts.

One day they arranged us in groups of 12 men. Each group was given two kilo of bread. We divided the bread among us and a march of 45 kilometers to the west began. An order was given that we should walk in straight lines and everyone who will stray from the line – would be responsible for his death. We were tired, broken and exhausted, and it's clear that we weren't able to comply with the command. Eli Schnitzer was the first to stray from the line and was shot on the spot, in front of us. He, may he rest in peace, remained lying on the road and we weren't able to bring him to a Jewish grave.

From Pirtin we came to the town of Boryspil. When we arrived two German officers came towards us. Each held two drawn pistols in their hands and they started to “harvest” us. It was a terrible massacre and only 50 survived out of a group of 150 men.

It was in the months of September–October. Snow and torrential rain fell and it was terribly cold. The non–Jewish prisoners were placed in a barn and we were abandoned outside. We stood for about two hours exposed to the intense frost. Those, who have not yet reached the point of exhaustion, started to dig a pit with their hands. We went down to the narrow and dark pit, one on top of the other, and so we lay all night.

In the morning we continued to march down Via Dolorosa – in the road of suffering and torture until we arrived to Vasilkov airport. The barbarians didn't end their acts of murder and extermination, and when we got there only thirty men were left.

We stayed in Vasilkov Camp for a week without food and water. The hunger and the thirst were terrible. When I saw that all hope was lost and I was going to die of starvation, I took a gamble and jumped over the fence to the Ukrainian prisoner camp. I was lucky that no one realized that I was among them. The next day I saw from a distance how the Ukrainians attacked our young men, undressed them, left them naked and stole all they had.

In this situation, it's not surprising that our young men literally begged the Germans to shot them. More than that: when they saw a man falling from the murderers' bullets, they envied him and said: Look please and also see. How lucky is this man! But the Germans, may their names and memory be blotted

[Page 394]

out, pretended to be “righteous” and said: Gott behüte! – Germans don't shoot humans. Germans don't do such repulsive acts with their hands. The murderers knew that they have someone to rely on because the Ukrainians will carry out the murders in no less “talent” than them.

Boryspil was the last stop for the Jewish prisoners. All the Jews were eliminated there. From here on, only the camps of Ukrainians prisoners kept moving forward. Ten thousand men marched in each convoy and I, the lucky one, was one of them. The convoy moved in the direction of Kiev.

For the first time I felt sort of a “pleasure” in walking. What was the pleasure? The convoys of Jewish prisoners were escorted by mounted Germans and the unfortunate had to adjust their steps to galloping of the horses. Those, who lagged running behind the horse, were hit on the head with rifle butts and pickaxes' handles. The Ukrainian convoys were escorted by Germans who walked along them. For that reason I said that I felt kind of pleasure walking.

At night we arrived to a place near Kiev. We were brought to a large identification field. My eyes were blinded by the big bonfire. The woodpile reached the height of a two story building. I was told that they were only looking for Jews. We lined up in rows of five men. They brought each row closer to the big fire, took a good look at the prisoner's eyes – and those suspected of being a Jew – were taken out of the row and shot on the spot. Those, who were only wounded, were thrown to the field and their screams were horrifying.

We were only given a slice of bread and soup. The bread was moldy and it was impossible to eat it and the soup was foul water. We arrived to a train station and they loaded us on the cars. Two hundred men crowded in each car. The density was terrible and many suffocated on the way. Fortunately, I stood next to a window and somehow enjoyed some air. Many jumped out of the cars, but they were shot by the Germans. There were those who managed to escape. We arrived to Shepetovka. I decided to escape, no matter what. I took advantage of the chaos that arouse during the unloading of the prisoners – and escaped to the forest. I ran like a hunted animal through fields, swamps, pits and virgin forests until I arrived, after a great deal of wanderings, to Kovel.

I came from Lutska Street and passed by the viaduct. I entered the first Jewish house that I came across and asked what was happening in the city. I was told that a ghetto hasn't been established yet and the Jews still live in their homes. I arrived to our house on Ludimir Street and the members of my family were frightened when they saw me because I looked different. I was injured, dressed in rags and my bones protruded from hunger. I didn't feel the change in me. After a month of illness I started to think about a job.

[Page 395]

The director of the department of labor in the Judenrat was Moshe Perel z”l. When he learned about my return he sent someone to call me for a private matter.

I went to him. He invited me to his room. He talked to me very kindly and coaxed me to get a supervisor electrician job in the new barracks that were being built behind the new cemetery on Ludimir Street. In those days there was a lack of certified electricians in the city. Aharon Zimmerman, the only certified electrician, was exhausted from all the work.

The Germans didn't accept the excuse that there was a shortage of electricians. They appeared in the Judenrat, created havoc, broke furniture, beat the members of the Judenrat and shouted: “give us electricians!” Moshe Perel was very happy when I accepted the job at the barracks. When I went to work on Ludimir Road I didn't see single Jew. Each time I walked by the cemetery I stopped and peeked inside. There was a lot of neglect. The Ukrainians cut off the trees and when they fell they broke the stones. I looked at this destruction from afar, but I couldn't help. I remember that one day the wife of Leib the undertaker came towards me shouting loudly: “who gives permission to the hooligans to defile and desecrate Jewish holy places.” She asked me to “influence” the Ukrainians not to desecrate the cemetery. I approached the gate. Not even single tree was left in the cemetery and the stones were cracked and broken.

A short time later I got a job at the Municipal Electric Company and worked there until the establishment of the ghetto. One day, an order was issued that all the professionals must obtain a work certificate and concentrate in the ghetto in the “sand dunes.” I went to the Community Council (the Judenrat) to get the certificate but I couldn't find it. There was disorder this area. There were those who had two certificates and those – who had none. There was a lot a pressure to get a work certificate and the members of the Judenrat were powerless to satisfy the all the demand. Having no choice, they closed the office and left. A lot of disgruntled people broke doors and windows, burst inside and grabbed the certificates. The thirst for life was so great that the owners of the certificates imagined that it was a barrier against disaster, kind of an alliance with the Angel of Death.

I stayed with my brother who lived at the house of Yehazkel Perelmuter z”l on Listopadova Street. Yitzchak Boxer z”l, one of the leaders of the Judenrat, lived with my brother. When I got there I found Boxer as he was making himself a lot of cigarettes. I asked him the reason for it, and he “innocently” told me that the “Gebietskommissar” called the members of the Judenrat for an urgent night meeting that would probably last till morning. The poor man didn't know that he was summoned to “Heaven.” This was the final road for him and for all the Jews of Kovel…

[Page 396]

by Zalman Poran (Prossman)

Translated by Sara Mages

September 1939. The great bloody erupted, thousands of refugees streamed eastward and many of them arrived in Kovel. All the rainbow colors of Polish Jewry “decorated” the city's streets.

The first to notice this horror of humans, uprooted and hunted like wild animals, was Reb Nehemiah Ber, may Hashem avenge his blood.

He puts aside his business, why should he have a wife, why should he have children. With great enthusiasm he begins to organize the relief work for the masses of refugees. He confiscates the building of “Talmud Torah,” installs a soup kitchen, gathers foodstuff from the silo and the winery – from the rich, the municipality and also from the Christian residents.

|

|

Our respectable Jews with the city's rabbi, R' Nachum Moshe'le, at the lead, move heaven and earth: Is it possible? Have you heard such a thing? A non–kosher kitchen! They feed the Jews carcasses and treif [non–kosher food]. Reb Nehemiah, who wasn't afraid of these words of rebuke, calmly answered: On the contrary, please, open a kosher kitchen and I'll close my non–kosher kitchen. However, as long as there is no other kitchen – I'll not close my kitchen. When it comes to saving life, I'm sure that God would forgive me.

R' Nehemiah's house takes the form of a train station. Various refugees run around there day and night: simple Jews, rabbis, authors, public activists from Greater Poland

[Page 397]

and even nuns. Everyone is seeking shelter at R' Nehemiah's house in the hope to revive their soul.

R' Nehemiah confiscates buildings by force and places refugees in them. He surprises his neighbor, Gitel Prosman, a widow with three orphans who lives in a narrow room, a very small room, and to this “palace” he stuffs eight refugees. The poor accepts it all with love and her lips mumble silently: R' Nehemiah knows what he's doing.

R' Moshe Schiffer is a laborer who lives in “Kovel Vtoroi,” At midnight someone knocks on the door to his room. Who is knocking? – R' Nehemiah! He came to ask for the well being of a sick refugee who, as he was told, is bedridden for several days without food and medicine. R' Nehemiah carries in his bag a loaf of bread and a bottle of medicine. He must discover the whereabouts of the sick refugee and give him treatment and healing despite late hour and the grave dangers that lurk in the city's streets.

The Red Army captured Kovel. R' Nehemiah welcomes the Soviets with fanfare. Now salvation will come to all who suffer. However, soon came the disappointment, and again, the burden of social welfare rests on the shoulders of R' Nehemiah. Again, he provides help to the miserable and the hungry until the German murderers took his life.

I know, from reliable sources, that R' Nehemiah walked to the pit of death upright and with Jewish national pride.

by Freida Rosenblatt–Buchwald (Paris)

Translated by Sara Mages

In 1939, when the Red Army entered Kovel, there was also a change in the field of education.

Three kindergartens were organized. Two – on the “dunes” [the area of the new city where the Jews lived], and one – in the city. Another kindergarten, of only one class, was established in the city a year later.

The large kindergarten, No. 1, which contained three classes, was managed by Sonia Margolis–Gelman. The teacher of Kindergarten No. 3 was Sugia Imberg. I forgot the name of the teacher of Kindergarten No. 4.

The education work in these kindergartens was conducted in Yiddish, but a respectable place was dedicated to the study of Russian songs and also for readings in the Russian language.

The fourth kindergarten, which was marked by the serial number 2, was managed by the writer of these lines

[Page 398]

and its language was Russian. This kindergarten was a mixture of different nationalities and outside the Jewish children it also contained Ukrainian, Polish and Russian children. The latter were children of Soviet citizens who came to the city with the Red Army.

The pedagogical and the administrative work were conducted under the supervision of the Municipal Department of Education (“Garana”) which was directed by the supervisor, Ida Merzan (today in Poland), who was an expert in kindergarten affairs.

The tuition was very small. The parents paid according to their ability because each kindergarten was given a decent budget to meet its needs. The children stayed at school until six in the evening and received three meals a day. The kindergartens were well organized and the toddlers spent their time in a cultural atmosphere and under reasonable conditions.

Most of the pedagogical and technical staff in all the kindergartens was Jewish. The young teachers, who have completed their education, worked on their own and performed miracles in the education work during the two years of Soviet rule in Kovel.

The ruling spirit in all the kindergartens was Soviet–patriotic and the trend was to empty the kindergartens from their national Jewish content and give them the character of Russian schools. The Jewish cultural heritage, which was woven with great devotion by many generations of Kovel's Jews, faded right before our eyes

Apart from Sonia Margolis–Gelman, the director of Kindergarten No. 1, and the writer of these lines – all these young kindergarten teachers were killed by the German murderers.

I will light a memorial candle for my beloved and unforgettable friends who worked together with me until the last days of the Jews of Kovel: The warmhearted Meika Gelman who was always smiling; the lovely Rozek Lifshitz, wife of Moshe (Moske) Gelman; the talented Asia Atlas who was devoted to her work; the young and cheerful Neche Sass who didn't know what sadness was; the gentle Yenta Tesler who wanted to leave the city when the war broke out. When she came to see me before I left she told me with a sad face “it's difficult for me to leave my family”; Sima Imber, the beautiful and talented principal. I will also bring the memory of the elderly women from the technical staff: Mrs. Wilkomirski, Berger and others that unfortunately I forgot their names; the nurses Tania Kutzin and Heinech.

In the years 1939–41, I directed Kindergarten No. 1 which was located on Prison Street across from the orphanage. The kindergarten was housed in a beautiful building which was full of light and surrounded by a big flower garden. Sixty to eighty children attended this kindergarten.

[Page 399]

|

|

[Page 400]

As stated, most of the children in this kindergarten were Jewish and the rest – the children of Soviet officials, and also Ukrainian and Polish children. All the work was conducted in Russian.

The children were divided into classes. Stasya, who was once the director of Maclerz–Szkolna [Polish Educational Society], worked in the toddlers' class. The second class was directed by Asia Atlas – a teacher of high professional level.

This kindergarten had an accountant, a storekeeper, a nurse, a doctor (who visited twice to three times a week) a technical staff, a cook, maids, and even a security guard who also worked as a gardener. The garden was full of flowers and the playground was the most favorite place for the children.

The work stood on a high educational level. The care for the child was felt in the daily work of the teachers and the technical staff. The children loved the kindergarten and willingly visited it. However, there was no a trace of Jewish education in it. Weekdays and holidays were dedicated to the introduction of Soviet patriotic spirit in the hearts of the young students.

In the picture we see the children of Kindergarten No. 2 during a large Soviet celebration in 1941. Here are Karteplie's grandchildren: Gita Guberman (daughter of the lawyer Yakov Guberman); Ruth (granddaughter of Yisrael Pruzansky); Sokna, her brother and her nephew – the children of the Porshtler brothers; Shapira's son; the daughter of Ester Murik, and the daughter of Riva Chasis. We also see the teacher Asia Atlas, the Berger friends, Schneider the music teacher and others.

As I was told, all these children, apart from a small group of Russian and Polish children, were murdered.

Shrinka Gvirtzman, the graceful daughter of Siake and Yasha Gvirtzman, left for Russia together with her mother but died of meningitis in far away Shakira before the end of the war.

In 1940, at the advice of the Soviet authorities, many Jewish families left for the depth of Russia. Some were hesitant to take their children to such distant places. They took them off the railcars at the last moment and gave them to their relatives “till the storm blows over”. Two of them attended our kindergarten and perished together with all the children. One was the three year old daughter of Riva Chasis–Rubinstein and the second – six year old Ruth, daughter of Liza Pruzansky and granddaughter of Yisrael Pruzansky.

Ruth was very talented and sang and danced well. She's standing before me in her colorful Ukrainian custom and I look at her delicate face.

[Page 401]

She was the one who danced and sang in that Soviet ball. She welcomed the guests, greeted them in Russian, a language which was still new to her, and also gave a speech.

The audience was very moved by the performance of the little artist and the chief administrator took her in his arms and kissed her. Full of glamour, her face flushed, she escaped from his arms and like a pure cherub flew, in one jump, on the stage and continued to dance and sing. Dozens of Jewish toddlers, who were dressed in colorful clothes, sang and danced with her.

This was her “swan song” – her last dance.

by Leuba Galman-Goldberg

Translated by Sara Mages

When the war broke out I lived in Warsaw. I worked as a counselor at a summer colony of a large Jewish orphanage.

When Warsaw fell in October 1939 we brought the children back to the institution. Some were sent back to their relatives and those, who didn't have a relative or a savior, remained in the institution under the management's supervision and care.

On 25 November I returned to Kovel which has already been under Soviet rule. The main train station was decorated with pictures of the leaders of the revolution, Soviet government personal and many flags. Uniformed soldiers ran all over the place. However, there was also an unusual movement of masses of civilians, Jewish and non-Jewish refugees, who arrived to Kovel from Western Poland on their escape from the Nazis.

Immediately after my arrival to the city I noticed that all the shops and businesses were closed. The shopkeepers sold their entire stock and didn't receive new merchandise. The only stores, which were opened and sold various goods, were the government stores and long lines snaked by their doors. It was impossible to get anything without a line. Obviously, the grocery stores “won” the longest line.

The only place where it was still possible to buy something was the market. Women, whose husbands were exiled to Russia or were in captivity, and the refugees sold all sorts of things to revive their soul.

All life in the city had been transferred to new tracks.

Craftsmen, who previously worked separately, organized in cooperatives: sewing, shoemaking and hairdressing. In addition, the banks have changed their way of working.

There was no longer a question of current accounts, loans and investments. A large government bank was created from all the banks. Each institution had an approved budget and all the proceeds were given to the bank. All the previous bank employees continued to work at the government bank. Among them were: Moshe Perel, the kindhearted Rachel Fisher, Monik Goldberg, Fira Efrat and Aharon Sokolovsky, who excelled in their devotion to their work.

The various factories, meaning, the flourmills, tanneries and olive presses were nationalized and their owners were exiled to small towns around the city. Among the deportees was Yosel Shochat and others. Denziger and Zimerman were exiled to Siberia. The Siberian exile was also imposed on political activists who opposed communism in the past, such as the “Bund” activist Steinman.

However, not everyone had won the grand “prize” to reach Siberia. On the way, near Tambov, the Russians began to eliminate the deportation trains. Aharon Tsuperfain, hy”d, was killed on the spot and Noah was wounded. The guards thought that he was dead and left him there. When he woke up, he somehow managed to stay in a village near Tambov where he recovered from his wounds. He immigrated to Israel in 1950 and passed away in 1953. May his memory be blessed.

As stated, many refugees who tried to settle in the place “until the danger is past,” gathered in Kovel. The city suffered from a terrible shortage of housing and it was necessary to house the refugees in synagogues and various public institutions.

There were also thousands of Ukrainian refugees in the city who arrived from the other side of the Bug River. According to an agreement between Germany and Russia, the Bug was set as a final border between the two countries.

Residents of rural villages, who were fascinated by the stories about the good life in the kolkhozy, loaded their belongings on their wagons and left to enjoy the wealth of the collective farms in Russia. However, the disappointment wasn't late in coming. They returned in masses and got stuck in Kovel.

To find a solution to the problem of unemployment and severe overcrowding, the authorities started to enlist people for work in Russia. They also announced the registration of those who wished to return to Poland.

Those, with a Communist outlook, registered to work in Russia. They wanted to help the “Socialist Homeland” in its desperate struggle against the Nazi monster. However, when they realized that this help was expressed in hard labor in mines with criminals - their enthusiasm faded and they returned to the city.

Different was the fate of those who expressed their wish to return to Poland to reunite with their families.

They never reach their destination. One night, they were collected, loaded on freight cars and exiled to Siberia. Despite their terrible living conditions most of them survived and a few even managed to immigrate to Israel.

Those, who remained in the city and received Soviet citizenship, gradually found a job and earned a living. A revolutionary change occurred in the occupation of the city's Jews. Suddenly, there were Jewish railway and factory workers. The educated received jobs in the various services - schools, hospitals and government offices.

With the entry of the Soviets, a number of Jewish Communists, refugees from Warsaw, established schools in our city. The Chief Inspector was an army officer and a former teacher. His deputy was Tabachnik-Mirsky, a native of our city. The comptroller of schools was Chaya Mendelson z”l, and the kindergartens - Ida Merzan.

All the schools were divided according to the origin of the students. The language of teaching at the Jewish schools was Yiddish, the Russian children were taught in Russian and the Ukrainian children studied in Ukrainian. I remember the impression that Talmud Torah had given me when I visited the school in the past. The big gray building, the yard empty from trees and greenery, the bearded teachers and the students that poverty and suffering were reflected from their eyes. But now, a different spirit hovered over the children. Singing emerged through the open windows. They were dressed in clean clothes and the girls were decorated with colorful ribbons.

The school teachers were: the talented principal, Aharon Shnitzky z”l, the principal of the Yiddish School of “Poalei Zion Left” in Warsaw (on Karmelicka Street); Lea Diamnt a teacher from Warsaw; Teitlker; Neumark z”l; myself and the nurse Mina Bidnick.

The students studied, drew, cut and paste pictures. Each class published a newspaper, danced and sang.

Also the image of the yard had changed.

The neglected yard turned into a vegetables garden. Each class had a number of beds that the children cultivated and guarded,

I remember the May Day procession. Our school received an award for a fine walk and there was no end to the children's delight.

Of course, all the religious holidays have been canceled and studies also took place on the Sabbath and on the holidays.

Our first celebration took place on New Year Eve 1939-40.

The Ministry of Education sent a Christmas tree to each school. The children decorated it in good taste and joy. The parents, Tabachnik the schools' supervisor, and soldiers attended this party. The children acted, sang and danced. The soldiers played the accordion.

It was strange to see the children of Talmud Torah dancing around the Christmas tree which is the symbol of Christianity.

I don't remember who initiated the unification of children from different nationalities, but the Ukrainian school on Meziov Street invited the students of the first grade to the party.

Military officers took an active part in all areas of life. They lectured at schools, kindergartens and in the parents' meetings. They told about the heroes of the revolution and the war in Finland. There wasn't a single party in the city without the presence of the representatives of the Red Army. They also invited the children to perform before the soldiers at the camps.

In our school, apart from the regular studies, there were also classes for working youth who hadn't finish elementary school, and classes for the illiterate. The teachers were sent, in turn, to rest-houses in Kiev, Kharkiv and Crimea. The children took field trips to Russia.

On each vacation the teachers took classes in sociology and Russian pedagogy. They also had to study the book “Kartki Course V.K.P.B” [Vsesoyuznaya Kommunisticheskaya Partiya bol'shevikov] by Stalin. From time to time, the teachers were invited to the “politrukim” [political commissars], the men of the Communist Party who tested their knowledge in the history of the Bolsheviks. Clerks and laborers had to study Stalin's book in all the institutions.

This activity was conducted with great energy until the outbreak of the war between Russia and Germany. In its wake, the Soviets were forced to evacuate the city. During the evacuation, the teachers tried to save the children in various ways. One successful experience was done by the teacher Zechindy whose husband worked in the municipality on behalf of the Soviets. She transferred the “Komsomol,” the students of the Jewish Gymnasium, to Russia, and indeed, all of them survived and most of them are in Israel.

During the Soviet rule in the city, the Jewish youth was filled with faith in the lofty ideals of Communism. They dreamed of pursuing further education in the universities of Kiev and Kharkiv, and believed, wholeheartedly, in the omnipotent power of the Soviet Union. No one imagined that the Soviet troops would leave the city for a long time, too long for the children of Kovel and her Jews… They were proud of the rights that the Soviet regime had given to them after they have been abused by Polish rioters.

Therefore, the youth's world darkened when the Nazis entered the city. In an instant, the Nazis canceled and trampled all the rights that the Jews had acquired, and not only that, they also denied them the right to live. From pride and hope they've sunk into the abyss of despair.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kovel', Ukraine

Kovel', Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 09 Aug 2019 by JH