[Page 470]

The Road to the Partisans and Liberation

by Dov Bargel

Translated by Monica Devens

On the morning of Erev Sukkot 1942, I escaped the ghetto with my son. From here on, a period of trouble and wandering, hell on earth, in the full meaning of that word, begins.

Our first stop was with a Ukrainian acquaintance, who received us warmly, fed us and gave us drink, and demonstrated honest participation in our great tragedy.

While we were with this good and nice man, we happened upon a Ukrainian woman who worked in the forest. She revealed to us that the Ukrainian Korets police were not far away and that they were setting up a hunt for Jews. They had already captured many of them and killed them. But the woman calmed us and promised us that she would not reveal our whereabouts in this place to anyone.

The heart prophesied evil for us because we suspected her, did not believe her words, and did not want to rely on miracles. We decided to flee from that place.

A Polish man of my acquaintance named Kotshinsky lived five kilometers away. We made our way to him. We went, gripped by fear and dread along unknown paths. We heard the rustle of the forest trees and our hearts beat with every whirring of the leaves. From afar, we saw light emerging from the window of one of the houses. We came close silently, slowly, we glanced inside and we saw our Polish acquaintance sitting at a table with his wife. Next to them sat a man whom we did not know. They were talking among themselves about Jews. The guest expressed that, should a Jew fall into his hands, he would immediately turn him over to the Germans. He made a terrible impression on us and we fled from the house. We remembered that the brother of this Pole lived not far away. Bent over and hunched, we laced our way in the darkness of the forest. We would have been happy had the earth swallowed us alive. After much work, we reached our goal. A black dog fell upon us who looked like a predatory wolf. The Pole came out of his house and, upon seeing me, whispered in my ear to flee immediately and not tarry because there were Ukrainian policemen in his house. They had come looking for his son whom the Germans had drafted for work and he had fled.

We entered the thick forest. Rain began to fall, we got wet and the cold ate at our flesh. It was Friday evening. The hours passed and the rain did not stop. We were tired and we looked for a place to lay our heads. We sat on the wet ground and supported one another. We considered our tragic condition. Woe to us that this is what our fate is. We trembled from cold and fear. We fell asleep and, when we awoke, morning was upon us. We looked at the pleasant surroundings, we looked at the beauty of nature, and we walked back and forth in order to warm ourselves.

We suddenly heard someone walking in the forest. This was the Pole, Kotshinsky.

[Page 471]

He moved with us, joined us in our sorrow, and brought us bread and warm potatoes. We begged him to save us and hide us in some place. He was afraid to hide us in his house because one could expect a sudden visit from the police at any hour and advised us to remain, for the moment, in the forest. While we were in the forest, I thought about the fact that two weeks had passed since we had fled from the city, we are wandering and meandering and we still hadn't come across a single Jew whom we could ask whether any of the Jews of Korets were still alive. We had to go deeper into the thick forest, perhaps we would happen upon a survivor or a refugee.

The Pole told us that Jews who had fled from Korets were a few kilometers away, in Lyubomirke. We happened upon abandoned hotels in the forest and we learned there that, in truth, people were living in them. And in fact we met a group of Korets Jews who had managed to escape. I found about 20 Jews, men and women. The meeting was very emotional and we cried bitterly about our terrible fate. I remember some of their names: Avraham Bardach and his children, the blacksmith, Meir Góralnik, Moshe Góralnik, and Zvi Rayzberg. I asked them what they were planning to do and they said that this was their place until the fury passed, that they would not continue wandering.

I was of the opposite opinion. I was convinced that, the farther we went from the surroundings of the city, the greater our chances of being saved.

It was a sad and cold autumn night. The cold really bothered us. We got up off the wet ground and went to find the home of a villager from among my friends. We saw light shining from one of the houses of the Ukrainians. We went in and to our great surprise, we found a Ukrainian policeman there. This one asked the farmer, who and what are we? I fabricated a story that we were thirsty and had come to quench our thirst. The policeman said: give them water, let them drink and go away. We left the house and looked behind us, was the policeman not shooting at us.

The moon lit up the sky. We walked and did not know to where until we arrived at the Sluch River. On its bank we spied a deep pit, full of stones. I said to my son, let's go down into the pit and lie there until morning. Tired and afraid, we fell asleep in this surrounding. I woke up to the sound of threshing as one of the farmers beat his grain in the threshing floor. I asked him how to cross the river and he showed us the correct way. We continued on our way and sunk into deep mud until we arrived at the bridge bent over the river. On our walk we happened upon a Jewish boy from Korets, Yossel Kachka, who was also exploring and looking for Jews. He joined us and we wandered together.

The road was messed up with swamps and lakes of water. Poor and wretched Poles lived in this area. We asked them whether perhaps there were Jews in the area. They told us that many Jews had left these places and were hiding, close-by certainly, in the nearby forest. We continued on our way and suddenly heard people speaking Yiddish not too far away. We followed the voice until we came

[Page 472]

to a large group of Jews from among the refugees of Korets. The group was about 30-50 men and women. Among them I found Yaakov Rubin and his son, Motl-Michael, the tailor, and his two children, Motl Shikher and his girlfriend, and others whose names I do not remember. We discussed among ourselves raising money to buy defensive weapons from the Polish population. Lamb to the slaughter was over. If the murderers attacked us - we would return fire and defend ourselves.

We set up our tent in the forest. We gathered trees, we lit a fire, we roasted potatoes, and we cooked cabbage roots that we found in the fields. We revived ourselves. We lived in the forest like this for four weeks. Once, on one night, hurried and frightened, Jews who had hidden in the forest in Lyubomirke came to us. They told us that the fact that they were found there was known to the Korets police. The murderers surrounded the forest and murdered many Jews. Aharon Schenker and his wife and children, Aryeh Barav, Yaakov Katz, Meir Góralnik, Moshe Góralnik, Sonya Finklestein, and Avraham Bardach and his children were among the murdered.

They told us that the police knew that we are here. This “news from Job” [=tragic news] sowed despair in our hearts and with every rustling of the leaves, our hearts shook like the movement of trees in a forest. The Poles in the area warned us that we should flee from the forest because the police were following us.

What should we do? Where can we flee away from the murderers? The enemy has locked us in. Rain was falling and soaked us through to the bone. Two months had already past since we fled from the city and we are wandering in forests and lakes of water and are being chased like wild beasts. We hadn't known even one night without insomnia. Our clothes were wearing out. And the most awful: the enemy had already murdered about 100 Jews who had fled and about 100 still are wandering and there is no end to their torment.

One night, we heard an exchange of fire. Our hearts actually stopped beating. With the last of our strength, we moved forward into the thick forest. We split into small groups and many left us without returning. We decided to walk on the swampy ground of the forests because we heard that there were partisans in the area. Perhaps they will take pity on us and add us to their ranks.

Along the way, the villagers told us that Yudel Kleiner, Moshe-Motl Kleiner and his daughter, Etel, were not far away. In one of the thick forests, we met Jews from Korets and Selashtesh. They spread out in the forest and slept under the sky. We discussed organizing and going to seek out the partisans, to accompany them in order to defend ourselves against the murderous groups that appeared in the forests. The roads that led to the partisans were filled with danger. We wandered in green forests, we sunk in deep swamps, and only a step was between us and drowning. Night fell. We didn't know which way to turn. We sat on the wet ground, lit a fire, and warmed ourselves. We sat like this until dawn. We continued our wandering until we reached Baber. We found many Jews there from the towns of Polesie [=region in Poland]. We went

[Page 473]

together to the houses of the Poles. They welcomed us, but they were afraid to let us sleep there for fear of the German and Ukrainian police who were searching for partisans and Jews. They had been warned by the police that anyone who let a partisan or Jew stay in his house would be punished to the greatest extent of the law and his house would be burned down.

November 1942 arrived. It was the height of winter. Because we saw no sign of partisans in the area, we started to think about a permanent settlement in the forest. We built huts which we covered with tree branches. They were called “karnikes” [=burrowing beetles]. It was impossible to completely stand up in them, but only to sit bent over. We lit fires on the ground, but it went out because water got in and our feet were always wet. These huts were really only graves for the living. In such a grave, there were generally about 20 people. The crowding was terrible and the dirt made a name for itself. Life was unbearable. Epidemics broke out and many got sick. And yet, despite everything, we thought ourselves happy because many Jews did not even have a hut like this and they sat day and night on the ground that was covered with snow and frost. Many died of hunger and cold.

Shneur Velman, Wolf from Selashtesh, Malka and Azriel Link, and Zelig Charif with his son were together with me and my son in the hut.

The inhuman conditions left their mark on us. The wretched began to fall like flies. Yudel Kleiner, age 55, Yaakov Rabin, age 30, a woman by the name of Shifra from Korets, a young girl from Rokytne, Kozyol, age 20, and many others were the first to die. My son and I became sick as well and we lay under the open sky on the snow-covered ground. My illness was so life-threatening that for a long time I was unconscious. But God took pity on me and did not give me over to death.

We lived like this for four months, from September 1942 when we fled from the ghetto in Korets to the end of that year.

January 1943 arrived, winter was severe and cruel. A lot of snow fell and the cold went down to 25-30 degrees, almost to strength running out due to the wretched living conditions. The Polish population that had been supportive of us stopped because the Germans punished the Polish villagers and burned them up.

Nonetheless, the desire to live overcame everything. We wanted to live and to be able to see the defeat of the Nazi murderers, the greatest haters of the Jewish people and of humanity in general. We wanted to remain living witnesses to the great Jewish tragedy. This hope invigorated and strengthened us in the terrible struggle with the ravages of nature.

On the morning of one winter day, a time when there was an awful snowstorm, we all got up, all the refugees from Korets and the surrounding towns, we got up and decided firmly - to go and search for the partisans. We put our hope in them.

[Page 474]

Finally we were able to reach the partisans. They were in a village that was populated by Poles. They welcome us. A partisan guard spoke with us and asked, where are we from and where are we headed. We told them everything. They brought us into one house and presented us to their leader. We asked him to add us to the partisan ranks and we would fight together against the Nazi murderers. And how great was our disappointment when he refused to accept us because we had no weapons. He chose only those of us who had a weapon in his hand. And these were: the brothers, Moshe and Motl Kleiner, Yisrael Fuchs, Itta Shapira, and a few others from our city. The large majority of us were forced to return to the forest.

However, due to the fact that the partisans were wandering around not far from us, strength and confidence infused us. They would visit the Polish villages frequently. In the village of Vinnytsya, they got rid of a Ukrainian, an agent of the Nazis. This murderer caused Jews a lot of troubles. They caught him, shot him to death, him and a few other murderers. The partisan movement continued to expand. The towns bustled with the weaponry of the avengers and redeemers. Jewish youth flowed to the ranks of the partisans of their own free will. Lyuba Vilner, Yaakov Yatum, Berel Basyuk, and Herschel Esterman were among the first volunteers. Tragically, they were killed by the enemy after a short time.

When the Germans learned that there were partisans in the villages of the Poles, they set heavy fines on the inhabitants, burned down houses, and carried out great slaughter of the local population. Rumors were widespread that the Germans were intending to set a trap in the forests to discover Jews.

This evil rumor alone grabbed us with a sort of insane mood and we decided to flee for our lives. We swallowed enormous areas without stopping. We passed on paths where no one had set foot before. We arrived at a hut with no doors and no windows. Dry hay was strewn on the ground. There was a stove inside with straw on it. We got on top of it, covered ourselves well so that no one could be seen. Suddenly, we heard footsteps coming closer to us. I saw a woman with a child standing and looking inside. This was a Jewish woman from Korets, my neighbor from those days. It was Riva Finkelstein, the daughter of Yitzhak Horenstein, and her husband was Siyoma Finkelstein. The Germans had murdered the husband a long time ago and now she wandered alone and lonely with her only child. She told us that Germans were near and had already managed to murdered some Jews. Riva left us because she was going to look for refuge with a Polish family whom she knew and my son and I continued our wanderings. We returned to the forest near the village of Vinnytsya. We met there Jews who had fled from Korets and from Selashtesh. We learned from them that the Germans had murdered three young men from our city: Berel Basyuk, Moshe Yatum, and Michael Kaminstein.

All the huts were already taken and we were forced to erect a hut for ourselves. While

[Page 475]

|

|

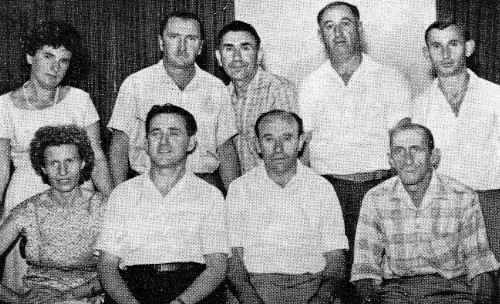

A Group of Partisan Fighters in Israel

First row standing (from right to left): 1) Shalom Raver, 2) Shmuel Kaufman, 3) Itta Kersch (Shapira), 4) Simcha Gildenman, 5) Azriel Beitchman. 6) Yitzhak Feiner

Second row sitting: 1) Yisrael Fuchs, 2) Chava Schorin, 3) Zvi Pe'er, 4) Yaffa D (Chimenes), 5) Leah Beitchman (Feiner), 6) Esther Feiner |

we were occupied with work, we had an exceptional surprise: we had a visit from two women of our city - Batya Gilman and Sarah Shikher, the daughter of Alik Rosenberg. Her husband, Yosef Shikher, and their small child were murdered by the Germans on Erev Shavuot 1942.

After a few days staying with us in our hut, Sarah Rosenberg-Shikher left for a nearby settlement in order to bring food, but she was not able to return to us. Anonymous villains murdered her on the way. Batya Gilman left us, too. I remained with two Jews, sick from cold and hunger.

I felt that all hope was lost and if I did not find shelter in a warm house, maybe even for a day or two, I would not be able to hold on any longer. A Polish acquaintance became my fate and my aid, who brought me into his home, gave me underwear, fed me a warm meal, and offered me a bed. Someone who has not experienced these trials cannot imagine the joy that sleeping in a bed gave me. After months of “sleep” on the cold and wet ground, however, the hours of happiness passed very quickly.

[Page 476]

On the second day, my generous benefactor told me that the Germans were moving around in the area. He hitched his wagon and told us that he would take us to a safe refuge. We traveled for six kilometers and came to a high mountain with a dilapidated hut next to it. The farmer told us, you will sleep here, and I will bring you food tomorrow. He returned to the village and we remained alone. The place was desolate and terrible. There was no living soul to be seen. We were sure that the end had come. But we never thought of suicide. The thirst for life was very great and we decided to adjust ourselves, somehow, to these terrible conditions. With my weak and limp hands, I cut branches from the trees and started a fire to warm the body, frozen from cold. Darkness fell. The darkness was terrible. I fell to the ground and lay next to one wall and my son lay next to the opposite wall. In this manner we fell asleep for a short while. Suddenly I heard a shout and sighs from my son. The fire had gone out and darkness reigned in the hut. I went to him and he shouted that his hands and feet hurt from the dampness and the cold. I tried to calm him down, but he called out that death would be better than life like this. I lit a fire to see what had happened to my son. I was seized with fear when I saw that his entire body was covered with insects and bugs and between them a large snake sprawled the length of my son's body. I picked up a log and began to fight these pests. I overcame the snake, I crushed his skull, and I threw him into the fire and burned him up.

I got sick again and couldn't stand. We were both sick and we thought that we would lose our lives in this place and no one would know where we were buried. The food was finished and we were literally starving. The Pole had stopped bringing us food because he was afraid for his “hide.”

The appearance in our hut of three Jews from Selashtesh brought us a spark of hope. They appeared happy and joyful and encouraged us not to be downfallen because the end of the Ashmadai [=demon] was approaching. The winter of 1942-43 came to an end. On one of the nights, we heard that many people were approaching our hut. These were Jewish acquaintances from Korets and Selashtesh. They told us that the Germans were following them and so they had fled to here. We welcomed them as guests and brought them into our hut. Yaakov Pikovskiy, (he was ill) Yossel, the shoemaker, and his wife from Selashtesh, Meir Krautopfsich and his son, a boy from Selashtesh by the name of Gorfinkel, and one woman, Netka, with her 16-year-old daughter were among those who came. The congestion and crowding were unbearable. But what could we do?

One morning, two men appeared and looked into our hut. They held loaded rifles and aimed them at us. They asked us, what were we doing here and who are we. We told them everything. It turned out that there was no reason to fear because they were partisans. The next morning, we heard a great noise and immediately afterwards, fire and smoke were seen from the direction of the village of Vinnytsya. We learned that Germans had come to the village looking for Jews

[Page 477]

and partisans. They set a few houses on fire and demanded that the Poles reveal to them where the Jews were hiding. However, it must be said in praise of them that they never turned a Jew over to the German murderers.

Our situation became serious because bands of Ukrainian murderers, who knew the pathways of the forests and the silent places, began to operate. I continued to wander with my son in the forests covered by lakes of water, perhaps we would encounter partisans along the way. We went 30 kilometers and came to the village of Pipleh. We saw human footprints in the snow. We happened upon a group of women and men, counting about 50 people. These were Jews from Korets and the surroundings. I found Pesach Kertzer and his son, Wolf Shtadlan and his brother, the Velman brothers, Chaim-Abba Gutman, Asher Adelman and members of his family, among them. They told us that there were Russian partisans in the village of Baber, about 20 kilometers away. We plodded through mud and snow and arrived at the village. But, unfortunately for us, we found scorched earth. The Germans had erased the village from the face of the earth because they knew that it served as a center for Communist partisans.

In inhuman conditions - fear, cold, hunger, and epidemic - we lived through the winter of 1943 until March. The spring approached, the snow melted, the water covered the fields and also came into our huts. Nature revived, the earth brought forth grasses and flowers, the trees flourished and celebrated. The creations of nature gave joy and praise to the Creator. This splendor aroused mixed feelings in us. Sorrow and joy were mixed up. We were happy because we hoped that, with the coming of spring would come our liberation. Nevertheless, on the other hand, sadness gnawed at our hearts, remembering wonderful Korets, remembering that we had lost that which was most precious to us, our loved and unforgettable families. I remember that my son brought me, in the darkness of the hut, a flower that he had picked. I said the “Shehechiyanu” blessing over it and cried with a broken and torn heart that we Jews had lost so much young life because of the German “civilized” animals.

In May 1943, we learned that Russian partisans, under the command of Kovpak, were in the Polish settlement of Matshulinke. All of us, our youth, our elderly, our children, arose and went to this place. We came upon a partisan guard. We announced to them that our idea was to join them. Their commander appeared, a doctor, and asked us, what are the motivations that have brought us to join them. We answered: we want to fight the greatest enemy of the Jews and of all humanity. The doctor chose the healthiest young people from among us. He declined to accept anyone over 40. The pleas of parents who wanted to go with their sons were of no avail. With a broken heart, I parted from my only son and remained alone and abandoned in the world.

These young men from our city were accepted by the partisans: Moshe-Wolf Milrod, Motl Shikher, Motl Kleiner, Moshe Kleiner, Chaim Bargel, Berel Huberman, Perelmuter, Herschel Esterman,

[Page 478]

Avraham Esterman, Moshe Powonzak, Wolf Shtadlan, and many young men from other cities. A few of them remained alive. The great majority fell as heroes at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains fighting the German fascists. As I have mentioned, these fell in those hopeless battles: Lyuba Vilner, Yaakov Yatum, Motl Shikher, and the brothers, Motl and Moshe Kleiner.

Although we were rejected as fighters, we worked with the partisans in the fields that they had conquered. They also employed Jewish tailors, shoemakers, and blacksmiths. Yisrael Fuchs, Yaakov Glozband, Berel Lipin, and Zelig Charif worked with them. And so we lived with the hope that soon we would be saved from the Hitler exile.

The “Days of Awe” came. Although all the days of the year had been awful days, three minyans of Jews, men and women, gathered in the hut where Asher Adelman and his family lived. It is impossible to describe in words the holiday prayer in this hut. The prayer, “U'netaneh Tokef,” took on a very concrete meaning. With a torn and agitated heart, we wished each other that we would be saved, we, the small handful of Jews, for whom fate had been so bitter, that every one of us was like Job, that we had lost our sons, our daughters and our wives, that our home was destroyed and plundered, that we were harassed and chased like wild beasts, that there was no shelter for our bodies and we lived in pits and caves like ancient people, that there was no bread, that our bodily strength continued to decline and we didn't have the strength to stand, and all around us, fear, terror, and darkness. We cried a lot about the bitter Jewish fate. We were Jewish believers and we remained tied to the world of the Holy One, Blessed Be He. We had not sinned against God and we were not uninspired by Him. Why did the Almighty make our lives so miserable?

Cold winds began to blow, the winds of autumn. The trees dropped their leaves. The forest was exposed. The Jews who were in the forests began to prepare for the winter of 1943-44. In our area, truly, partisans moved about, we saw them, and they seemed to us as angels of salvation. That inspired confidence. We got rumors that the Germans had begun to retreat and that the Soviet army was advancing and crushing the Nazi enemy. However, bands of Ukrainian nationalists started to appear in the villages, they rioted against the Jews and killed many of them. There was a fear of remaining in the forests and we advanced following the partisans. While I was walking in the forest, I saw a cart, hitched to two horses, and two Russians, singing and happy, on it. They stopped and asked me who I was and where I had come from. I told them all my “genealogy.” They told me to get on the cart and they told me the good news that the Red Army had conquered Kiev [=Kyiv], and that's why they were so happy and joyful, and now they were going to the headquarters in the village of Vinnytsya.

I happened to meet a Polish acquaintance who welcomed me and invited me to stay at his house until the day of liberation. He told me that there were Jews in the village. I went to look for them and I found

[Page 479]

Yitzhak Feiner and his family, Berel Lipin and his wife, and several other families. I felt myself happy that I found myself among Jews of our city.

At daylight on January 4, 1944, men and women from the neighboring village came to us and told us that a vehicle with 20 soldiers on it had come to the village, but they didn't know if they were Russian or German. Later, we learned that they were Soviet scouts. How great was our happiness to see them and to be saved from the German murderers. There were also Jews among these scouts, who had been sent to the front. They became very emotional to see us because they were convinced that no trace of the Jews remained. We spent a few days in the company of the soldiers until they left us to advance to the front.

I met Yitzhak Feiner, Berel Lipin, and many other Jews from other cities. We put together a list of Korets Jews who were still alive and were wandering in the forests. The number reached 75 men, women, and children. We decided to leave the forests, whatever might be, to follow the Soviet army, which already had control of the entire area. The Soviets welcomed us and gave us food and drink. They showed us the way to Korets and, after many hardships, we returned to the destroyed city.

* * *

[Page 480]

This is How I Took Revenge Against the Murderers …

by Zvi Pe'er

Translated by Monica Devens

From the first moment that the unclean feet of the Germans stepped onto the ground of Korets, I prayed, when will the time come when I can take my revenge on the Ukrainians who murdered our parents and children with the sadistic pleasure of wild beasts. In truth, these descendants of Petliura were the first to begin the blood sacrifices. Apparently, they waited for this window of opportunity when restraint would be released and they could do to the Jews what their hearts desired.

The Ukrainians were sent by the Germans to capture Jews and to torture them with all manner of hard and contemptible work. During work, they beat them and tortured them with no hint of mercy. Once I sat in Beila Reizberg's house and looked out the window. Suddenly I heard a Ukrainian shout: Jew, stand up! I stuck my head out and saw Baruch Goldberg with a little Ukrainian boy standing next to him. This disgusting insect abused Goldberg, tore out the hair of his beard, kicked him everywhere, and dragged him by force to the river. Baruch walked like a dumbstruck sheep and the little murderer - after him. My blood boiled, my patience was at an end, and I wanted to help Goldberg, whose face was filthy with blood. When the little murderer saw me, he fled for his life and in this manner, I saved Goldberg from certain death. I stood on the bank of the river and sought to steep in its waters. As I went into the water, I saw two Germans accompanying the Ukrainian boy coming to meet me, they grabbed me and took me to the church. On the way, their blows amazed me and I cannot describe the vast cruelty that these human beasts revealed. When I got to the church, I saw a Jewish man lying on the ground upon whom a Ukrainian was dancing, jumping, and leaping while singing: “Ukraine is not yet lost!” I asked the murderer, why are you torturing this man? He looked at me with his murderous eyes and said: wait, wait, in a little while your fate will be like the fate of this Jewish leper. I looked at the victimized Jew and saw that it was Meir Serota. He was completely covered in blood and mud, and I only recognized him with difficulty. I was sure that I, too, was going to have this bitter and cruel fate, but there was no escape because the area was surrounded by Ukrainian police.

Suddenly, a German officer came to me and shouted: come here, Jew! And he immediately put me to cleaning the bathrooms. He liked my work and he asked me if I would like to continue working for him? Obviously, I said yes. He equipped me with a suitable certificate and sent me to work behind the sugar factory, a place where there was a warehouse full of explosives. The entire area was strewn with grenades and bombs. My work was to travel with the Germans to nearby villages, to bring food from there, and to cook for 40 Germans. My first thought was

[Page 481]

to poison the murderers, but I considered what this matter would profit since with this deed, I would bring about a holocaust and an end to the remaining survivors of the Jews of Korets. I continued, therefore, with my work and fulfilled my task faithfully.

Nevertheless, I knew that this life was given to me as a gift and that, sooner or later, they would bring me to Kozak and my fate would be the same as that of all my brothers. Therefore, I did not give myself false hope and I began to think about fleeing, not only in order to save my life, but rather in order to take revenge against these horrible murderers. While we were still in the ghetto, we organized a partisan unit of 12 men. We had a little “weaponry” - Purim toys, wooden guns. With these “powerful” instruments of war, we went on our way and in our hearts the firm decision - to kill, to eliminate, to slaughter as many murderers as possible. We were thirsty for the blood of the plunderers.

We walked in the fields of Golovanitsya [=Holovanivsk?] and came out to the Yuzfovka road. We saw on the horizon a few pairs of bicycles approaching us. These were Ukrainian policemen. Motl'eh Reizberg and I decided to let them approach and when they got close to us, we shouted: “Hands up!” They were surprised and obeyed our command to throw down the bicycles with the gun bag that was on the back.

[Page 482]

Motl'eh aimed his wooden gun at them and threatened them that if they lowered their hands - they were responsible for what would happen. I went to the bicycles and took two rifles. Motl'eh put the rifle on his shoulder and gave the Ukrainian his wooden gun while teasing: look, look at with what a Jew can put the fear of death in you. - Correct, one of them said, only a Jewish leper is able to do something like that. - Have no fear, Ivan, Motl'eh said, I will kill you with your rifle, but not with bullets because it's a shame to waste a bullet on a dog like you. And like that we finished them with the rifle butt, one after another.

We hurried to get to Yuzfovka. When we got to the forest next to the village, we became aware of two houses. We woke the gentiles up and forced them to harness the horses. We took the reins in our hands and turned toward the village of Hoshcha. When we got close to there, we saw that Ukrainian police were chasing us. We decided to cut through the village and whatever would be, would be. We traveled at such a speed that the policemen were frightened and scattered in every direction. We broke into the police building and found boots, uniforms, and weapons, enough to equip an entire company. The most important things for us were the certificates, typewriters, and telephones.

We took all these possessions, crossed the Sluch River, and we sent the two gentiles who were with us in the cart to a “rest home” in the Garden of Eden … Darkness fell and we hid in a forest not far from the village of Mys Chekhova. We waited until sunrise in order to continue on our way. When we started out, we heard the rattling of cart wheels and horses' neighing. We were convinced that either the Germans or the Ukrainians had followed in our footsteps and were chasing us. Carts of gentiles loaded with huge vats revealed themselves. We jumped from where we were and ordered the gentiles to get down from the carts in order to inspect what was in the vats because, most likely, they were hiding explosive matter in them. We found milk that was going to the Germans. They broke out in tears because the Germans would murder them if they didn't supply them with milk. We gave them a letter that said that the milk had been taken by partisans. The letter was stamped with a seal that we carved out of a large potato. In this manner, we freed the gentiles from their fear of the Germans.

At nightfall, we continued on our way. At 1 in the morning we heard the sound of steps and immediately after it: “Stop! Stop! Who's there?” (in Ukrainian). We loaded our weapons and prepared to meet the enemy. However, it became clear that these were partisans. We shouted at them: don't fear, brothers, we are partisans of the captain “Dyadya Misha.” We asked to join them because all the time we were working on our own initiative, but because we were hungry, because it had been three days since we'd eaten, we arranged to meet them at a particular place the next day, and in the meantime we went to the nearby village to get food.

[Page 483]

We came to the village and woke up the “Sołtys” [=head of the village council]. This one, when he saw us, changed his colors like a chameleon, became pale and red alternately, because he knew what to expect. We instructed him to prepare food for such and such many people, emphasizing that anyone who did not immediately fulfill our commands - we send him straight to the Garden of Eden … we asked him to send two men with him to bring the food, but he said there was no need for that. We understood that he wanted to cry for help and we immediately eliminated him. We entered the animal pen, slaughtered a fat sheep, and cooked it until morning to prepare provisions for the journey. We left the village at dawn and waited for the partisans who should be arriving, in accordance with our agreement. They came on time and we continued walking with them. In the afternoon hours, we came to a forest in which 140 Jewish families were hiding. We had to find a secret place for these families so that they would not die from hunger or from attacks by the enemy. We decided to go to the “Pinsker blottes” [=huge mud mess]. On the first night, we had to pass under a bridge upon which a train passed and it was liable to be heavily guarded. We succeeded in getting the Jews over peacefully. With our weapons in hand, we approached a lone house in the forest. We took two oxen from the farmer and some loaves of bread. The adults ate the meat and the bread was given to the little ones so that they would not die of hunger.

And so we continued night after night. During the days, we lived in hiding. We got more weapons day by day. We took every pistol that we found with a gentile and no one dared to stand up to us. The conditions of our lives were cruel: the first snow served as a pillow for our heads and the next snow that fell served as a blanket.

But we had a great comfort: we had started to take revenge against our enemies with all our strength and might. We liberated Jews from concentration camps and we sabotaged the Ukrainian murderers. And thus we continued until Brynsk - hungry, thirsty, and tired.

In the forests of Brynsk, we began to feel the hunger in all its horrors and wonders. The weapons helped us get food where there were settlements. But in these places, there was no trace of a settlement nor was there any sign of a living soul because the Fascists had burned the villages that were along the border. And should Soviet planes approach us with the intention of parachuting food and ammunition to us, unfortunately, they were not able to save us because we were surrounded by four German battalions. However, this fact did not scare us and we continued with our war until we reached a place where there were many storerooms full of food, which the Germans had brought for the border patrol.

When we returned to full strength, we began to pave an airfield in order to permit the Soviets to bring us food and explosive materials. Paving of the airfield only took a month because a lot of people worked on it. The first planes supplied us with a little weaponry and a little explosive materials that helped us to punish the murderers.

[Page 484]

In one village, we spread out in the houses because we decided not to add to the “arukh galut” [=long exile] in the forests. I felt that the owner of the house was a close associate of the Jews and I told him that I was a Jew from Korets. He hugged me and, after I promised him that I wouldn't let his neighbors know, he told me that there were Jews hiding in the nearby forest and that there were Jews from Korets among them. I asked him to take me to them. He was hesitant to go with me out of fear of his neighbors, but he showed me the way. The place was unfamiliar to me because it was several hundred kilometers from Korets. Still, that fact didn't deter me. I took a machine gun with me, I got on a horse, and I came to a village. Suddenly, I heard people speaking Yiddish. I looked hard and saw two young women in front of me. In order not to frighten them, I spoke to them in Yiddish, I asked them to come closer and not to be afraid because I was a Jewish partisan. I asked them: where are the Jews hiding? They got scared because they suspected that I was a Ukrainian spy. One of them said to the other: “Dead once, but not twice.” They were already used to these things. In order to test whether my words were truthful, one of them brought a “siddur” out from under her shirt and said to me, if I could read it, it was a sign that I was a Jew, and if not, that I am but a spy. I took the “siddur” and, with a bitter voice, choked with tears, I recited “kaddish” for the elevation of the souls of my wife and son. The girls cried with me, a crying that split the heavens, and told me to join them.

We entered a thick forest and walked a path that wasn't really a path. When I arrived and found a large congregation of Jews, I became aware that it was Friday because I saw the Jews praying next to a campfire, which was lit within a small hut. The Jews stood around it and their faces were sooty. The children asked for food and the wretched parents cried bitterly because they had nothing with which to feed their children.

I asked them if there were Jews from Korets among them. They answered that the Schorin family from Korets was there, but that they were a little distanced from this place. A boy brought me there. I found Mrs. Schorin as she was lighting two sticks instead of candles. Her grandchildren slept around the fire. There were another 40 people there - hungry, thirsty, and worn out. She told me that these little ones were her daughter's children and that she and her husband were no longer alive.

I spoke to the people in order to strengthen them, that there were many partisans in the area. I stayed with them all night. I left the next day and after a few days, I returned with a cart full of everything good. The matter was life-threatening, but I saved a lot of Jews from dying of hunger.

When the Jews recovered from the hunger and disease that afflicted them, we began to move toward Ukraine. Our general asked all the Jews that were hiding in the forests to come out from their hiding places and join us. On the way, we took our revenge against the Ukrainians, we expelled them

[Page 485]

from their homes, barefoot and naked, and we set their homes on fire. And anyone who uttered a word - we burned him and his home.

With our own eyes, we saw how the Ukrainians caught Jewish toddlers and smashed their skulls with wood because “for a small Jew like this, there's no need for a bullet.” I was sorry that I didn't have enough time to stay in this place to take out all my anger against these murderers. We had to advance as commanded. I was lightly wounded and I was sent to a hospital in Rovno [=Rivne]. When I got out, the commander asked me if I would like to go to the border or to fight the Nazis. I told him that I wanted to fight the Nazis, but only in the area of Korets because I know the murderers well whose hands spilled the blood of the Jews. He did as I wished and sent me to Korets. I was appointed commander of a company of 32 men. We went into a village, and just as we heard a shot, we immediately incinerated him and his men. Later, the order came not to kill, but rather to expel the inhabitants to a place we thought good.

Nevertheless, however many we killed, we still couldn't put out the fire of revenge that burned in our hearts. Only someone who saw what the Ukrainian rampagers did to the Jews - only he can understand us. We were crueler than wild animals. We lost the feeling of mercy and our own humanity. When we saw the blood of the Ukrainians, our hearts became lighter. We felt that, in this way, we were fulfilling a holy obligation to our martyrs. We were hungry for the blood of the murderers. The smell of their filthy blood calmed us, quieted our tumultuous and raging blood.

And if you ask how I became a wild animal - let me tell you what the Ukrainians did to me: they tied me to a tree with a wire and I remained bound hand and foot for four days without food or water. But that wasn't all. They spit in my face, beat me, and lit a fire under my feet that licked at my body and covered it with awful wounds. And so that I would not escape from the fire, they set a guard to watch over me until I died. Miraculously, I was saved by a Ukrainian shepherdess, the sister of two Ukrainian policemen, who listened to her insistent pleading, killed the guard and saved me from death.

Small, very small, was the revenge that we took against our enemies. We were very far from fulfilling the command: “Now go and utterly destroy any remnant of Amalek from under the heavens.”

* * *

[Page 486]

Wandering

by Yakov Pe'er

Translated by Monica Devens

The Germans did not begin murdering right when they entered the city. They suppressed their Satanic goals very deeply and aroused in us the delusion that surely they had no intention of harming us.

However, the murderers revealed their true intention quite quickly, that the central point of their coming was to kill, to eliminate, and to destroy the Jews of Korets. On one bright day, SS companies arrived and began to snatch young people for work or to assemble them in one of the courtyards and beat them murderously.

My father worked in the German slaughterhouse. One day, Papa came with terrifying news because he had heard rumors that a slaughter of the Jews would take place the next day. We decided to hide in the slaughterhouse, which was out of danger.

We lived next to the house of Azriel and Malka Linik. I went to their house in order to take his son, Gershon, with me. His daughter, Sarah, was at the house at that moment. As I waited for Gershon to return, I saw that the street was filling up with German policemen. Sarah broke out in a terrifying voice: Papa, we're lost! When I heard her voice, I jumped to the garden with Gershon and we began to run in the direction of the river. Sarah jumped, too, and hid in the garden next to their house, but a “goya”[=gentile woman] discovered her and turned her over to the Germans.

The Germans shot at us, but they didn't hit us. We went into the “Feines” neighborhood in the new city that was mostly populated by Christians and we mixed ourselves together with them. We're still walking and two armed German police are coming towards us and shouting: Jew, stop! There was no escape so we made as if we were walking towards them. However, when they looked the other way, we escaped into the first courtyard. They chased us and we ran like madmen. Suddenly, I lost Gershon and I was alone, but when I got to the end of the city, I found him.

We spent the entire night in the attic of the slaughterhouse. In the morning, we heard that people were coming and calling loudly for my father: Herschko! At first, we were afraid, but when we heard that the voice belonged to the neighbor of the slaughterhouse - we calmed down. He told us that the Germans had taken several thousands of the Jews of the city for execution, but that those who remained alive would continue to live and no one would harm them. We could return to the city in quiet and without fear.

We didn't want to believe him. I said to my father, I will go and determine whether what he says is true. When I came to the city, I saw many Jews coming out of their hiding places - those who came up from a basement and those who came down from an attic. I found a wax seal on our house, meaning, the house was empty of Jews.

[Page 487]

I endangered myself and took the seal down. I didn't find my mother or my two brothers there. They had been taken the day before to the Kozak forest. Everything was turned upside down and destroyed. A huge pain took hold of me at the sight of the destruction and loss. From great distress, I fell into a deep sleep and I prayed that I might sleep forever because what's the point of life like this after those I loved the most, those most dear to me, were stolen from me forever. In my sleep, I heard noise and crying. When I woke up, I saw my father standing next to me lamenting the terrible destruction.

This was after the first “action.” After this slaughter, the ghetto was created in Shkolna Street. We lived in the Serota house together with Dvora and Faiga Kaftan. Our house served as a center. Misha Gildenman and his son, Yaakov Yatum, and Lyuba Vilner came to us and we began to think about acquiring weapons and about establishing a partisan unit. I served as a secret liaison.

A German captain, who was responsible for a camp of Russian prisoners, was also invited to our house. He knew my father because he used to buy meat for the prisoners at the slaughterhouse. This captain was a friend of the Jews and used to spend time with us in the evenings.

Once he appeared at our house and loudly announced: tomorrow all the Jews are lost because, following an order of his superiors, he had sent all the prisoners to dig pits in Kozak.

We didn't want to believe him. We sent a Ukrainian by the name of Hwadko Bachuntsik together with me in order to ascertain whether this awful news was correct.

On the way we had to pass by two villages: Vozdov [=Hvozdiv] and Kozak. The Ukrainians actually went crazy with joy. They danced in the streets and rejoiced: tomorrow they're killing all the Jews! Tomorrow we will bring all the possessions of the Jews and fill our houses with them!

When we got to Kozak, the “goyim” [=gentiles] told us that they had indeed seen Russian prisoners being transported in the direction of the Kozak forest and that, a day earlier, they had commandeered all the digging implements in the village. A lot of Ukrainian policemen were in the village and they didn't let us advance. We got to the place by side paths and we saw that, in fact, Russian prisoners were there and were digging long and deep pits …

On our return to the city, when we got to the wooden bridge, I met a gentile, one of my acquaintances, who began to shout: don't you see what's going on in the city? Don't return! Get up and flee! And, truly, I saw that many Jews were fleeing the city, they were running on the bridge, the Germans were shooting at them, they were dropping and falling into the river, and the water was getting red from their blood.

Having no choice, I returned to the new city, where there had not yet been a slaughter of the Jews. I found Lyuba Vilner and Yaakov Yatum in the home of one of the gentiles. They told me that Papa had gone to the village of Tatravka to get weapons and tomorrow we would all go out to the forest and join the partisans.

Azriel and Malka Linik came late in the night and said: we must flee immediately. The Germans already caught Gershon and we only escaped by a miracle.

[Page 488]

We all walked by way of the fields until we got to a farm. We saw that a Jewish boy was running to greet us. This was a Korets child. His name was Mumeh Shtekelis. He begged us to take him with us.

The owner of the farm brought us into his stable. There I found Michael Polichuk, Yossel Fajgowt, and a Jew from Warsaw who had lived for a time in our city.

The owner of the farm was afraid to let us stay there for any length of time and we were forced to go. We lost Azriel and Malka along the way. When I went to gather food in the houses of the farmers - I didn't find them when I returned. Thus I stayed with Mumeh only. We were two Jewish boys in an area where murderers roamed everywhere. We reached a second farm. The mistress of the house looked at me and I didn't understand the meaning of her scrutiny. After a few minutes of confusion, she asked me: are you a Jew? Don't be afraid. You're not alone. Other Jews are hiding close to this place. She took me by the hand and brought me to the hiding place. There I found Itta Shapira, Mitzia Vilner, Yesha and Fanya Molier. I told them what I had seen of the city going up in flames. They said to me: stay with us and when we move on - you will go, too.

After a few days, we decided to go to the village of Mys Chekhova. Along the way, we found a large group of Jews from Korets and from Zhvil [=Novohrad Volynskyy]. They were armed with one rifle only. These Jews aroused great pain. They were hungry and almost naked because their clothes had become shreds. We decided to return to Korets and bring the clothes that we had hidden before we fled from the city.

Next to the village of Istzia we happened upon a large group of Ukrainians who wanted to stop us. We escaped, but they caught “Nyuma Bilkele” and I don't know what happened to him.

Having no choice we abandoned the plan of returning to the city and getting the clothes. The cold was at its height. We camped in the forest and lit a campfire. The daughter of Serota sat opposite me. She said to the participants: look, please, the forest guard is approaching and he has another “someone” with him. We didn't pay attention to what she said and we said to her that it was a matter of no consequence. But suddenly she shouted: we are lost! And only then did we see that armed German and Ukrainian police surrounded us. Miraculously, we all managed to hide in the thick forest before the murderers could activate their weapons. Running through the trees, I happened upon Mumeh Shtekelis and his nephew, Herschel Shtekelis, but I lost them afterwards.

Once again I remained alone in the world. I looked for a way to connect with the partisans and my goal was to get to the village of Lavitshe, where organized and strong partisan units operated. Alone I got lost and wandered in the forests until it seemed to me that no human had ever walked there. I was subjected to storms and tempests and terrible cold. It is hard for me

[Page 489]

even today to understand how I withstood all this. As I was walking in the forest, I suddenly saw some kind of small campfire. But it was light shining from one of the houses. I decided to go in. The mistress of the house welcomed me and said to me: stay with us overnight. While she was still speaking with me, two Jews from Selashtesh entered. They told me that Jews from Korets were hiding not very far away. And, indeed, I found Glozband and Dvora Kaftan, and other Jews. They decided to walk to the village of Lanchyn. I joined them. When we got to the village, we saw that the residents were fleeing into the forest together with their cows. I asked them to explain and they said that the village was surrounded by the German army that had come to kill their animals. We fled for our lives.

Near the village of Lavitshe, I felt like my strength was leaving me. I sat on the ground and pondered, from whence would my help come? I will die and the dogs will tear my body to pieces. I summoned the last of my strength and, by crawling on all fours, managed to reach a house. They served me dinner, but when I left, I felt that my weakness was increasing. I couldn't stand up. With great effort, I crawled to the forest and sat on the cold ground like one dead. I was certain that this was the end and there was nothing to do, but wait for death.

However, the ways of life are mysterious. When the world became dark and I began to leave life - a bright light sparkled. With sunrise, I saw a small “sheygitz” [=gentile boy] going out to the field with his flock. When he saw me, he began to run as fast as he could in the direction of the village. I was sure that he was running to call the police, but I was wrong. He returned with an old gentile woman. She asked me where I was from and immediately returned, bringing me warm food and winter clothes. In the evening, her son-in-law came with an axe. He chopped down trees, lay them next to me, and started a campfire. I stayed in this place for six weeks and every day, the gentile woman brought me food and her son-in-law lit a fire so that I would not freeze from the cold.

Little by little, I managed to reach the village of Lavitshe, which was full of partisans. I found Itta Shapira there. She fed me and I stayed with her for a period of time.

After a while I went to a certain gentile to hide in his house. When I went out in the morning, I saw a large and numerous army surrounding the village. This was the Soviet army. One of the officers approached me and said: don't be afraid, my boy, the Nazi monster is defeated - we have liberated you!

* * *

[Page 490]

“To Be My Vengeance and Recompense” …

(Deuteronomy 32:35)

by Simcha Gildenman

Translated by Monica Devens

After the huge action that took place in May 1942 in which 1,500 Jews of Korets were killed, among whom were my mother and my 13-year-old sister - my father z”l began to exhort the Jews of the city to flee to the forests.

Shortly after, we went out to the unknown - to swamps, evergreen forests, and hard and difficult hazards of nature. We were a small group - my father, my cousin Siyoma Geifman, the sisters Dvora and Faiga Kaftan, Herschel Pe'er (Khavkes), Leizer (Lazik) Gershfeld, Avigdor Zayka, Moshe Milrod, Noach Reizberg, someone from Mezhyrichi whose name I do not remember, and the author of these pages. We had two pistols only.

We came in contact with the partisans and they showed us the way leading to a group of Jews. Our plan was to join these Jews and, with combined forces, to transfer the families across the front line. This group of Jews was armed with rifles and hand grenades. However, the goal was not achieved because, next to Klosova [=Klesiv], the Ukrainians discovered us and called the Germans. A powerful battle erupted between us. This was my first baptism of fire. I threw the grenade that was in my hand and two Germans were killed and one seriously wounded from the explosion. We lost Noach Reizberg in this battle.

Some of the Jews scattered and I remained with my father, Siyoma Geifman, Herschel Pe'er, and some other people from Berezne and Ludwipol [=Sosnove]. We decided to organize ourselves like a partisan unit, but we knew that our Jewish names would be a stumbling block for us and so we decided to change them for foreign names. Everyone got a nickname. I stopped being Simcha and got the name “Lyonke Semyonov” and I was known like this for a long time in the forests. Herschel's name was changed to “Grishke” and my father, whose first title was captain, was changed to “Dyadya Misha.”

We joined the large company of General Suvorov, which operated in the surroundings of Kiev [=Kyiv] and Korosten. I served as a scouting officer.

And here I must tell the story of my odyssey, the great journey, full of strength and drive, from Kalynkivits to Odesa, a distance of 2,000 kilometers.

And this is how it was: we had a direct wireless connection by means of airplanes. The camouflaged airstrip of the partisans was in the area of the city of Narowlya in White Russia. The airplanes would land at night, bringing with them weapons and food, and would take the wounded with them in return.

[Page 491]

In 1943, Khrushchev came to us on one of these planes and, close to his coming, the Germans bombed the airfield. We fled to the forests and Khrushchev stayed with us for two or three weeks until he was able to return to Moscow.

In April 1943, we got a notification on the wireless from the main command of the partisans signed by Voroshilov that, along the Kherson-Odesa line, scattered partisan units were wandering without any contact or connection to the command and, therefore, one of the partisans had to be sent to bring them a wireless device and, in this way, create a connection between these partisans and Moscow.

Because I served as the scouting officer, the lot fell to me. Voroshilov sent us from Moscow a young woman, an expert wireless operator who was also expert in “Morse alphabet.” There were twelve partisans under my command and we started out, each one carrying eight kilos of explosive material. The order said that we had to get to the target and return to our base within six weeks.

Along the way, we met many people who wanted to join the partisans. From them we learned that there were unlimited possibilities to sabotage the German strongholds. However, we were forbidden to take any action. In one place, they showed us a ton and a half of “trotil” (explosive material) that the Soviets had left when they retreated. We decided that, on our return, we would work out a plan to use this explosive material.

We got to the place and found 40 partisans there. The wireless operator stayed with them to show them how to use the wireless and we returned in the direction of the base. The fact of the existence of the explosive material pestered us. Look, an opportunity to take vengeance on the murderers of Jews was given to us. Fate invited me to avenge the blood of my 13-year-old sister who cried out from the pit in Kozak that she wanted to live.

We returned, therefore, to the place where the explosive material was stashed and we decided to stay there for two weeks and carry out sabotage actions. This was not far from Kherson. The partisans did not operate in this place. There were two coal mines there, which the Germans used for their war machine, and we decided to blow them up.

We got to talking with some of the local workers and learned from them that, on Sunday, work stopped. We brought almost 200 kilos of “trotil” to the main corridor of the mine and, in an instant, it turned into an avalanche wave. This was a hard hit for the Germans. Manufacture of their weapons in the area was almost paralyzed. The impression of this operation was tremendous and the Germans sought a stratagem to destroy us.

They set a trap for us in the shape of a young Christian man who appeared one bright day in our camp and announced that he had fled German captivity and his only wish was to join the partisans. He made a good impression on us and we did not suspect his sincerity. We accepted him, but still

[Page 492]

we treated him with caution. This young man was convinced that we were the command of a large partisan unit.

My people were exhausted from the huge effort and we decided to stay at one of the nearby farms. We set up a guard roster for the night. The guard switched off every two hours. When I was standing watch, I saw the young man coming to me and saying, I got up just now and I am prepared to stand watch in your place.

I believed him and I lay down to rest. After a short while, I heard that someone was waking me. One of the members said to me fearfully: there's no one standing watch. I immediately understood what had happened. I saw that my pack had disappeared, my automatic rifle was gone, and so was the young man.

I woke up all the partisans and I asked the owner of the house whether he knew where the young man had gone. He answered that that one had gone to a nearby farm and would immediately return. When we went outside, we saw that this young man was coming to meet us at the head of a German company, who intended to surround us. I saw that we had fallen into a trap. Luckily, there was a tall building and we managed to hide in it and to escape. We still had another 300 kilos of explosive material and we decided to use it. We waited a few nights in order to make the Germans think that we had left the place and, after we had rested, we blew up two trains.

One night, we gave ourselves a break and we lay down to sleep. When we got up in the morning, we saw that the fields looked as if they were covered in a blanket of snow. But we quickly understood that there were millions of notices, written in German and Ukrainian. When I took one notice in hand, I saw that it was written as follows: a Bolshevist gang, headed by a Jew from Korets named Lyonke Semyonov (in parentheses it said Simcha Gildenman), has appeared on the fields of Ukraine. This Jew has caused severe damage to the German army and the Ukrainian people. For his head - alive or dead - we offer a prize of 50 desitinas of land, two horses, a cow, and a sack of salt.

When we saw the notices, we decided to return to the base. We were sure that the rumor of these notices had reached there, too, and that they were probably worried about us.

We were young and full of imagination and, thus, we decided not to return to the base in our tattered clothes, but rather in nice clothes and riding on handsome horses, all in order to make an impression.

In the surroundings of Korosten, in a nearby village, we knew that the Germans had 150 milk cows for Gestapo headquarters and, in addition, 25 war horses. Germans guarded this camp, but they were few in number and their watch was somewhat weak. We decided, therefore, to steal the cows and the horses. We approached the place and saw that the watch was relieved every two hours. We waited impatiently for five hours. When the watch changed, one of us approached and, with a knife, murdered the German sentry. We went into the barn and we took the cows and the horses out.

[Page 493]

The Germans felt this, began to shoot at us, but were afraid to approach because they were few in number. The journey with the spoils took all night and we arrived at the base in the morning. They knew about the notices that the Germans had published and they feared for our lives. And furthermore, instead of six weeks, we had been gone for more than three months.

This operation was the biggest that I carried out during the time that I was a partisan.

Obviously, we were not always crowned with victory. The Nazi enemy extracted a lot of blood from us. Buzye Melamed was among those who fell in battle with the Germans. He was active with General Kovpak's unit. He participated in the great “march” from Polsiya to the Karpatim [=Carpathian Mountains]. Kovpak suffered great losses in the Karpatim [=Carpathian Mountains] and the young man from Korets, Buzya Melamed, fell in one of the battles.

* * *

[Page 494]

In the Storm of Battle…

by Chaim Bargel

Translated by Monica Devens

Summer 1941. The Nazi forces, armed with frightening tools of war, plundered, murdered, exterminated peoples and regimes under them, and there was no savior. In the skies of the handful of Jews - who remained in the area of the German conquest and wandered over paths that brought them eastward - there began to appear signs heralding a terrible storm that was coming to be felt.

The only path that remained for escape was closed by the cruel enemy. We were hungry, plundered, and broken. The fateful question nested in the heart: who knows what is ahead for us? The roads teemed with convoys of the conquering army. The Ukrainians felt that restraint was lifted, no law and no judge, and they accompanied us with mockery and ridicule.

We saw clearly what awaited us. Anyone with open eyes had no illusions or fantasies. The Nazis struck the gates of Moscow and had reached Stalingrad. The Soviets retreated when the enemy extracted much blood from them. It seemed that the Nazi flood would wipe out everything and those who made calculations about the end prophesied that the end of days had come.

Nevertheless, despite everything, we were not taken by the mood of “and tomorrow you and your children are with me” because the life force sizzled in us and it eradicated the spirit of gloom. We thought about flight and making connections with the partisans. From time to time, we were able to get information about what was happening in the area. From this information, we learned that there was an opening for rescue.

The Germans kept us alive as “useful Jews” and even my father, despite his advanced age, was not executed. But we knew very well that we were as raw material in the hands of the Nazis, leaving us alone as they wished, finishing us off as they wished, and thus we took advantage of the window of opportunity and prepared to flee. Knowledge about the digging of pits in Kozak for the final elimination of the ghetto sped up carrying out the flight plan. Two of my friends, Moshe Milrod and Mordechai Shikher, preceded me and fled to the forests, but I was held up a little because it wasn't easy to convince my father to leave home. Abba came back from the street and said that Ha-Rav Nisan Bashkin was comforted by the writing in the holy books that “even if a sharp sword was placed against a man's throat, he should not refrain from praying for mercy.” With great difficulty, I convinced my father that, in a time of trouble like this, we should not put our hope in quotations - and we went on our way.

We suffered much evil until we reached the partisans. We ran towards them full of joy. This was a company from Kovpak's unit. We found a lot of Jews among them, including Motl Shikher and Moshe Milrod. The meeting was very emotional.

[Page 495]

|

|

Partisans in the Mountains

The Artist: Chaim Bargel |

[Page 496]

The staff of the company headquarters asked us what we wanted. We asked them to let us join them. The medical examination found us fit to join them as fighters, but they refused to accept my father because of his age. I was completely tied to my father and I could not leave him alone in wild surroundings, where the Banderovits gangs roamed and plotted against the lives of the Jews. But my father was overflowing with feelings of vengeance and, with a voice choked with tears, said to me: “Don't worry about me, my son. Go and take revenge against our enemies!”

My first baptism of fire was in the village of Vilietchka [=Wieliczka]. We burned this village of plunderers and executed many murderers. From there, we continued to the southwest. We rested during the day, however at night, cruel battles, steeped in blood, exploded with the German forces and the Ukrainian police. We advanced on faulty roads, in swamps and pits. We blew up bridges and we penetrated, truly, the lion's den. We sabotaged German military facilities and we ambushed the reinforcement that was sent to the front.

In the beginning, I was not in the same company as my friends, Milrod and Shikher, but afterwards, I joined them. In our meetings, we would bring up the memory of our friends and our families and we were proud of that, that at least a few were able to be counted among the fighters who were protecting human dignity.

Kovpak's company advanced to the south. It had many victories, but they cost a lot of lives. The situation was serious and dangerous. The Nazis threw significant forces at the battle against us. The aerial bombardment caused much loss of life and equipment. Our scouts had informed us that the Germans were gathering large forces arranged to attack.

Moshe Milrod's life came to an end in the autumn of 1943. The night before, the three of us sat in the forest next to Ternopil [=Tarnopol]. The night was cold and rainy. The trees were bare. Moshe felt strong discomfort in his heart. It seemed that he had foreseen his soon-to-be end. But he saw in the sacrifice of his life something that had no escape because the Nazi Molech would swallow many more human sacrifices before it was overthrown and defeated.

With daybreak came “zero hour.” The two sides were arranged for a major attack. Moshe Milrod sat behind a “Maksim” machine gun and I assisted him. The enemy planes appeared and slowed down. The explosions plowed the area and the machine guns clattered without pause. It was impossible to lift up one's head. The command had been to not open fire. The shelling went on for a long time. The blood harvest was large. The wounded shouted, but we were powerless to save them.

When the enemy planes disappeared from the horizon, I got up and I wanted to say something to Moshe, but he lay still, without movement, and his hands were attached to the machine gun. The murderer's bullet had pierced

[Page 497]

his head and exited through his jaw. A large blood stain reddened his black curls. It was hard to stop the tears that choked my throat. Only a few moments before the bombing ripped out stalks of grain from growing, camouflaging the machine gun, and he said with great sadness: “look how much bread we are destroying with our own hands!” It was difficult to come to grips with the idea that Moshe no longer existed.

At dusk, we buried him among the bushes.

At that time, Mordechai Shikher was in another section of the front. I met with him one night. I told him that Moshe was gone. He received the awful announcement with absolute silence.

The Germans followed us ceaselessly. The bombing became heavier day by day. Through battles and heavy losses, we succeeded in sabotaging the enemies' oil facilities. Many Jewish young men fell in these battles. Motl Kleiner was wounded in his arm. I carried his canteen and his belongings and, from time to time, I changed the bandage on his wound. He was patient and controlled his pain.

One night, while we were retreating, he disappeared in the darkness and we never saw him again. In one of the battles, we were forced to leave our post and a squad remained there for covering fire. Moshe Powunczak, a young man from Lodz who had come to Korets with a convoy of refugees, was with this squad. This brave young man did not leave the machine gun until the last bullet was used.

We suffered significant losses in a battle in Delyatyn. Moshe Shikher fell in this battle, too. A tragedy befell us: when we crossed the Prut River, we stumbled upon a German ambush that killed everyone. Only I remained. I escaped and, under cover of night, I rolled down a steep wall into the river. Happily for me, the water was shallow in this place and I did not drown.

These are the ends of my stories about my life as a partisan. In reality, I stood before much more difficult and severe tests than I have the ability to describe.

* * *

[Page 498]

As a Paratrooper With the Red Army

by Zahava Me'iri (Serber)

Translated by Monica Devens

When the Red Army came into our city, the youth of Korets were drafted, and I among them, to the Komsomol [=Communist Youth League].

One day before the Germans entered, I left the city with the Soviet Army and came to Dnipropetrovsk [=Dnipro], where I met my aunt who lived in Krivorog [=Kryvyy Rih].

I had made up my mind to join the Red Army. The Germans were advancing at frightening speed and the danger of falling into the hands of the enemy hovered over me. On the other hand, I, too, wanted to contribute my part in the defeat and rout of the Nazi enemy.

The Komsomol Secretariat sent me to Rostov and there I was drafted into the army. Due to the seriousness of the situation, every young person with suitable fitness was drafted. After I went through a strict and meticulous physical and psychological examination - I was found fit for the Air Force. From there, they sent me to Stalingrad along with 200 other young women, non-Jews.

In Stalingrad, I passed a parachuting course that lasted half a year. After that, I was transferred to Leninsk (on the other side of the Volga) and there, too, I trained for six months. The training was extremely difficult. They would make us jump from a height of 100 meters.

When the German Army advanced towards Stalingrad, I moved with the Red Army to Sverdlovsk [=Yekaterinburg] and I found myself at the airfield in Aramil (near Sverdlovsk).

With the conquest of Rostov by the Germans, I started to operate as a paratrooper. I parachuted near Rostov for an operation behind enemy lines. I was there for two weeks, I came in contact with partisans, I gave them weapons and ammunition, and also important documents and orders.

Once a very serious and dangerous “incident” happened to me, where I only remained alive by a miracle. We sent a transmission to our headquarters that they should send a plane to get us. The transmission was heard by the Germans and when I flew in the plane, four German war planes came to meet us. An aerial battle between our plane and the enemy planes developed. Our plane was hit and began to burn. We were forced to jump. We jumped at a distance of a few hundred meters and, from afar, we could make out our burning plane. The enemy planes split because they were afraid to cross our defensive lines.

Headquarters feared for our lives because they had lost contact with us and thought

[Page 499]

|

|

Korets Red Army Fighters

Standing (from right to left): 1) Fraydel Gelfenbeun, 2) Chaim Fuchs, 3) Mordechai Berman, 4) Yesha Narbus, 5) Zahava Me'iri (Serber)

Sitting (from right to left): 1) Yosef Lazabnik, 2) Nisan Tsenter, 3) Mendel Brautman, 4) Ronis |

that we were lost. In the early morning, our forces found us. During the jump, I was seriously wounded in my leg and I lay in a hospital for about a month.

After I left the hospital, it fell to me to learn to drive and I began to work at an airfield. I drove an autostartior. This auto would approach an airplane and, by touching it, the motor would begin to work. This was very responsible and dangerous work because, although we were 60 kilometers from the front, the German bombers would visit us frequently. There was always an army doctor in my car whose task it was to give medical help to those wounded by the bombing.

In this fashion, I did my part in defeating the enemy. I felt myself to be a free person to whom was given the ability to take revenge with weapons in hand. The Soviet authorities tried to influence me to remain in Moscow and even equipped me with party membership. But my desire was to emigrate to Israel and, with the help of the escape activists, I emigrated.

* * *

[Page 500]

From the Horrors of Those Days …

by Yitzhak Kleiner

Translated by Monica Devens

On June 22, 1941, with the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, a public meeting was held in Korets under the auspices of the Soviet authorities, where they announced the outbreak of the war. And immediately after the announcement, convoys of the Red Army began to flow to the front.

About two weeks after the war broke out, Korets was bombed from the air by the Nazi air fleet. In this bombing, several Jews were lost whose names, unfortunately, I don't remember. Several buildings were destroyed, among them the homes of Asher Shikher and Sukenik.

About ten days, approximately, after the bombing, Hitler's army entered Korets. This entrance was accompanied by cannon fire, which did not cause noticeable damage, neither to property nor to lives.

In the first days, quiet reigned in the city and we waited with great tension as to what the day would bring. We immediately understood that this was the quiet before the storm. Not even a week had passed when the Germans began to draft Jews for work - for all kinds of work: mopping the floors in the soldiers' residences, from which the Jewish families had been thrown out; polishing shoes and bringing food and ammunition. This draft was accompanied by awful abuse: in normal times, a cart was drawn by a pair of horses, but the Nazis decreed that the best “horses” were Jews with long beards, and so they hitched six or eight “horses” like this to each cart. A German soldier sat on the cart with a whip in his hand and would whip the Jews as if they were horses.

The Jews cried bitterly, their legs failed, a lot of blood flowed from their scarred faces, but by the end of a work day, no one was let go, even if he was on the verge of death. And in fact, many of these “horses,” the best of the Jews of Korets, died even before the end of the day.

My grandfather, Yudel Kleiner, was among these “horses.” A God-fearing Jew who worked hard all his life and had never hurt a soul. When they freed my grandfather from being a “horse,” he would go to the neighboring villages and glaze windows in the homes of the Ukrainians in order to get a loaf of bread or some potatoes as payment for his work because there was no food and hunger bothered him a lot.

On the day before Shavuot 1942, we woke up early in the morning to the sound of shouts and shots. After a few minutes, the door of our house burst open and they took us outside. The corpses of many Jews, whose warm blood flowed like water, were scattered in the streets.

[Page 501]