|

|

|

[Page 205]

by Ginzburg

Translated by Nancy Schoenburg

The District City of Bielsk-Podlaski was the place where my maternal Grandfather Avraham Yitzhak Shochet and Grandmother Sarah lived. It was the second city after my birthplace of Suraz from which I have childhood memories from the age of five to the age of Bar-Mitzvah. I would frequently come to the District City of Bielsk. Sometimes my parents would just bring me to visit the home for the aged, or to see a specialist doctor or for clothes sewn by an expert tailor in the District City.

Grandfather was the head shochet [ritual slaughterer] and a cantor in the Bielsk community, and according to the lists that I found written in his handwriting on a page of the Guide to the Perplexed,[2] he came to Bielsk from Pruzhany between the years 5626 and 5628,[3] as he was promised good salary conditions here that would allow him to manage his household with sufficient means.

He received his salary from the “Korobka”[4] on every animal. Every butcher was required to add in an amount of money, and from these funds he would receive his salary, like the rabbi. This was approximately ten years plus before the War.

He did not receive money from the synagogue. Grandfather would sign his name with the initials AYS, which stands for Avraham Yitzhak Schochet. Apparently, he did not use the title “Cantor.” He said that he was just a prayer leader. However, on the High Holidays[5] he prayed Musaf[6] accompanied by the choir. He also composed many prayers.

My grandfather was good-looking in appearance, tall and upright, an imposing figure. He was strict about cleanliness and was exacting in his attire. He enjoyed purchasing nice things for the house.

While he respected secular things, he was scrupulous in his religious observances. His tefillin [phylacteries] were made of one piece of fine work and kept their shapes and black color. The portions inserted in the phylacteries were written by an accepted scribe, excellent in piety. And he gave tefillin like his to his sons-in-law, both to my father and to my uncle.

In his strictness in doing mitzvot, it came to this that he ordered a set of glass cylinders for rolling the Passover matzos because with glass it is easier to guard the kashrut of Pesach. This was his tradition of all the traditions and mitzvot to be precise with them both on the “outside” and on the “inside” at the same time.

Of the furniture in his house, what stands out in my memory are the antique clock in the dining room and the bookcase beside it. In the bookcase were two sets of Shas [Talmud] which were prepared for his sons-in-law. The books of Talmud have lovely bindings by the Vilna publishing house, Romm Publishers. In the same bookcase I was especially drawn to three prayer books that were bound with a beautiful leather binding: one was by Rabbi Yaakov Emden, the second by Rabbi Yaakov Nissim, and the third by Rabbi Yisroel of Mecklenburg. Each one had a different commentary. And when I would come to the house

[Page 206]

of my grandfather, I especially loved to pray using the siddur [prayerbook] of Rabbi Yaakov Emden ben Zevi. It had a variety of prayers and customs. It was a comprehensive siddur. He had beautiful Chumashim [Five Books of Moses].

He was also active in communal matters in the community. And as my father related to me, they called him in the city by the nickname “Bismark of Bielsk.” That is how much they appreciated his communal service work.

Grandfather had two sons and two daughters. He did not succeed in seeing that his sons were G-d fearing and learned in Torah according to his wishes and the direction that he taught them. They did not learn at a yeshiva and preferred to study at home. Naftali, his younger son, went to America and there he renounced his faith. But Uncle Shabbatai had already apostatized in his youth; he did not however, Heaven forbid, get into a bad culture. He was an apecoris [apostate] according to ideas of those days. His way was to probe the nature of the Creator and to grumble about the evil in the world. Regarding that which touches on mitzvot [deeds] between man and his friend he was very careful. He was a person of principle. He was the manager of a lumber mill that had many workers. He was beloved and popular with the workers and business owners with whom he stood in matters relating to trade and money. But when it came to deeds between man and G-d, he was not strict. He only kept kosher in regard to food out of respect for his father the shochet. The relationship between himself and my father, the rabbi, was such that they both wanted to respect each other despite their different viewpoints. Grandfather also respected him for his honesty. My uncle would travel by train on Shabbat to visit his father and Grandfather agreed with that despite the fact that in the city they complained about it.

If he did not have pleasure from his sons in regard to education as he had wanted, he found compensation from the marriages of his daughters. They were wise students, Shomrei mitzvot [followers of the commandments] in the way of the honorable leaders. In that same era there were his young scholars by his table until they were settled in the rabbinate or in trade.

The older son-in-law was my late father (z”l) the rabbi who ate kest[7] by his father-in-law, my grandfather, for eight years. After he received his ordination for the rabbinate from the Rav Shmuel Moheliver,[8] he was accepted as a rabbi in Suraz, which is near Bielsk.

For his younger daughter he took my uncle Reb Shmuel Katz as his son-in-law, and he was a shochet in his area of Bielsk. Grandfather thought that this son-in-law would be a rabbi, but it turned out otherwise. Grandfather was removed from his position because of his age and my uncle received the status of his father-in-law. He had to step down from his father-in-law's table. My uncle, Reb Shmuel, made for himself set times for Torah, even though he was working as a shochet. After his hours of work, he would sit and immerse himself in Gemorrah and its commentators, The Rishonim[9] and The Achronim.[10] He would also make new interpretations of the Law through pilpul[11] of Jewish Law. He was accustomed to writing down his new, personal interpretations and preparing them to be printed in a book. For his sharp-wittedness and his theories, he was accepted also in the home of Rabbi Moshe Aharon[12] and went to him to have a pleasant time for hours with the words of Torah. Many times he joined with the rabbi in a clarification of Halachot and ruling on Jewish law. He was also a test examiner of students at the Talmud Torah.

Bielsk was the District City; in contrast to my town of Suraz, it was in my eyes like a capital city. Its streets were paved, the stores were lovely and the city clock tower in the middle of the marketplace gave weight to its antiquity and loftiness. The beit midrashes in the city are very much etched in my memory. At that time there were five beit midrashes. The most beautiful was Beit Midrash “Yafe Einayim,”[13] which was in the center of the city. It was named for the famous book by Reb Aryeh Leib Yellin,[14] known for his marginal notes in the Romm Talmud from Vilna. He wrote the commentary “Yafe Einayim.” The congregation built the beit midrash.

[Page 207]

Professor Louis Ginzberg mentions Rabbi Yellin in his book on the Yerushalmi [Jerusalem Talmud]. He wrote about him that he [Yellin] was one of the first to engage in a comparison of texts between the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds.

The above-mentioned beit midrash was not just the center of prayer; it was also a meeting place for the study of Torah. During the day there were a few people studying Torah, but in the time between mincha[15] and ma'ariv,[16] they would come in from all ranks of society – artisans, shopkeepers and simple Jews and everyone studied. Each one sat according to his level of knowledge, in the group of Menorat HaMaor, Ein Yaakov, Mishnayot, up to Chevrat Shas[17].

Saba [Grandfather] did not live long after they dismissed him, and the house and everything he had passed to the possession of my uncle, with the exception of one room and the remaining furniture of Savta [Grandmother]. She lived with her daughter and son-in-law. All of this transition of authority from one to the next did not interrupt our visits to Bielsk. But in place of Saba's house, it was Uncle's house. However, the atmosphere changed. Instead of a spirit of the elderly and seriousness, a younger spirit came in as well as a younger life.

There were no schools in Bielsk, except the non-Jewish state school that the Children of Israel avoided. Only a few sent their children there. In those days there was no uniform curriculum for the cheders.[18] The curriculum in cheder was just prepared by the melamed [teacher] himself. Of course, there was a cheder with Hebrew studies, Chumash[19] and Tanach.[20] The special cheders were those that learned Gemara[21].

Homes did not have electricity or water. The bathhouse that they had was beside the spring and the plumbing that they arranged was not so modern that the water came into the bathhouse. The bathhouse was not managed by a public entity. The community leased it out to a bath attendant, and everyone who came there would pay.

There was a separate purification place [i.e., a mikvah] for women, though the bathhouse was for everyone. However, they took turns according to the day, a turn for women only and then a turn for men.

We would come by train to Bielsk. We would travel from our home to the station in Steblow. The station in Bielsk was in the city and there were also carts. Bielsk was near Bialowicz by the forest. Every Saturday they would bring money for the treasury of the kingdom from Bialowicz to the District City of Bielsk. The forests belonged to the king. The tenants would sell the wood and the money would be brought by car and deposited in Bielsk in the Treasury Building, which was a special building with police protection. That was the only automobile that would come to Bielsk and its environs. They did not call it an “auto” but “Chortu Braiki,” that is The Lilith -- the female demon. When they brought the money there, in the name of security, as I recall, all the people would go out to see the auto.

Bialowicz was a property belonging to the Czar. They would come there not to rest but for hunting. I remember that they would say about it that people came up there from Petersburg.

Prisoners would clean the streets. A prison was located there. I do not recall whether there were any Jews there. They would guard them so they would not escape. All year long the prisoners would clean the streets. I do not recall if it happened every day. There were separate walkways made of wood that were higher than the street and these the prisoners would clean as well. I do not recall if they sprinkled water over the footpaths.

My grandfather lived on a side street not far from the shuk [marketplace]. Not far from there lived

[Page 208]

non-Jews. They lived outside the city. One could not say that the city was Jewish and the non-Jews were an attachment. However, the gentiles were concentrated on the outside streets and in the center there lived only Jews. The non-Jews were engaged in agriculture. The Jews were mainly shopkeepers, wood merchants, doctors, butchers, bakers, artisans. There were no factories.

There were many craftsmen, even Jewish street cleaners. I did not know any Jewish builders; perhaps there were some individuals. There was Shimon the tile-layer. He got my attention, a sign that he was the only Jew [performing that craft].

Every Thursday was market day. They would bring in the merchandise, and there were customers in the stores, and those selling their wares.

There were tradesmen who were managers of commerce with Bialystok. Some like them would bring to Bielsk products made in Bialystok. The merchant would order products by letter, which would be sent to them by train.

Since it is a duty to tell about Bielsk and to preserve her image for the generations, I called up my memories of her. I hope that my words will not be a repetition of those that have already been told but will add a personal touch to filling out her image and complementing her charm.

Notes

(From “Sefer Reshonei Ramat Gan” [The Pioneers of Ramat Gan],

Published by the City of Ramat Gan)

Translated by Sarit Sachs

Chaim Radilevsky is the “White Crow” of the group called “The Maagal” [The Circle], not just because of his profession as a pharmacist. As is known, pharmacists wear white, but it is also because he is very far from Bialystok, the city where the group Maagal originated.

He is a man of Bielsk and there he was also a pharmacist and a truly active Zionist. When his friends one day delivered a present to him, they pointed out that next to a picture of businessmen from Bielsk was a list of all the activities that he fulfilled: Vice President of the community, member of the Zionist Committee, member of the Hebrew School committee, delegate to Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael [Jewish National Fund], member of the City Council.

He made Aliyah [immigrated] to Israel in 1921 and immediately started working in his profession. He worked in a Kupat Holim [healthcare clinic] in Tel Aviv, as its first pharmacist. And within the domain of Kupat Holim – on Mazeh Street – they created a room for him using fabric as a partition. And there was his first pharmacy in Israel. Somehow he got in touch with the “Maagal” [Circle] people (perhaps thanks to the textile connection between Bialystok and Bielsk –Bielsk was also a city with a textile industry. And maybe it was just by coincidence?) He purchased a five dunam plot of land and planted an orchard. He kept on working at Kupat Holim, but he settled in Ramat Gan, and enthusiastically devoted himself to his orchard, where he worked at night.

His widow (he died in 1958), Chaya Radolsvky [Possibly a misspelling of Radilevsky. An internet genealogy site has her maiden name as Redaitsky.] relates:

“The first few days in that place were difficult. We created two rooms made of cement, as was the fashion in those days because it was cheaper to build from cement than with bricks. For two years we lived without doors or windows, but the orchard blossomed. Chaim Radilevsky believed, as did most of the people who settled in Ramat Gan, that an orchard on such a small plot would be enough for an income when he would grow old.”

And his only daughter Ruth, who is married to a lawyer named Pojarsky, adds:

“I remember the hot days of picking the fruit. Father brought in workers to help and the work was done as feverishly as in a real orchard.”

But the fate of this orchard was as the rest of the orchards in Ramat Gan. It turned into a plot of land and on that lot today stands a large building. The Radilevsky Family created a two-story dwelling next to that building, and the mother and her daughter with her family live on the second floor.

Editor's Note:

Chaim Radilevsky appears in a photograph on page 171.

by Carmon

Translated by David Ziants

Reviewed by Andrew Blumberg

Every year before 1st May [International Workers' Day[1]], the Polish authorities used to arrest all communist elements and then release them after that day. This fact also came to pinpoint communists and to conduct a Polish-security selection in the city. Therefore, as long as the Communist Party of Poland was underground, its strength could be estimated by the number of prisoners on various occasions. There were quite a few Jewish prisoners in Bielsk. If my memory does not deceive me, according to the above indications, none of those who were suspected, of communism in Bielsk, came to Israel.

It is difficult to know, and in fact I don't know an iota about the fate and deeds of the communists in Bielsk in later years. But one of these people became very famous, far beyond the borders of Bielsk and even beyond the borders of Poland. We know a lot about him from Kibbutz Lochamei haGeta'ot [the Kibbutz of the Ghetto Fighters][2], even those who did not know him by face. This is Yoseph Levartovski.

He was much older than me and I never saw him, but I had heard about him and know his family. He has two sisters who live in Israel.

Yoseph Levartovski's father was a devout thick-bearded Jew. He was a longtime resident of Bielsk, and he had what the Poles called “olirania” [it seems from two Polish words, olej=olive and rani=wounds, i.e. he suffered from olive colored wounds or scars] - but not referring to the oil factory called “Shemen” [a well-known cooking oil factory in Israel whose name means “oil”] or oil from an olive press. The son Yoseph was, when he was young and in his youth, a member of Po'alei Tzion S'mol [lit. Workers of Zion Left – referring to the more radical left wing branch of this political socialist movement]. In the early [nineteen] twenties, Poalei Tzion S'mol negotiated with the Comintern [Russian Коминтерн – Third International, or Communist International, was an association of national communist parties founded in 1919] about the Po'alei Tzion S'mol party joining the organization. Nir- Rafalkes[3] was in Moscow for several months for these negotiations, and the negotiations ended with nothing. Poalei Tzion S'mol was willing to accept some of the basic theses of the Comintern, but on one condition: that the independence of the party will be preserved and that, in principle, the right of the Jews to immigrate to the Land of Israel would be recognized. Nir conducted the negotiations with Zinoviev[4] and Kaminev[5], and the history of these negotiations is written in a book that was also published in a Hebrew translation.

When nothing came out of all this, the matter influenced many people and caused a split in this party.

This happened in the early [nineteen] twenties, in 1921 it seems to me, and I learned the stories later on, more from hearing from others and study, rather than from my childhood memory. A small faction left Poalei Tzion and Yoseph Levartovski among them. Since then he hardly visited the town, because his life was underground [in hiding], and in Bielsk he had to be concerned of imprisonment. He was very active. His family may have known all the time where he was, but among the public not an iota was known and he was never seen in town.

Once, in Warsaw, when they were about to arrest him, he jumped from the second floor and broke a leg, so he had to lie in hospital for several weeks. People said that ever since, he was many [lit. seven] times over careful because there was still a mark left from this fall. This mark heightened his profile and the authorities stepped up their search for him.

The Polish authorities considered him one of the main organizers of the communist youth, and not just only the Jewish youth. For camouflage, Levartovski used all sorts of

[Page 211]

underground nicknames. He also spent some time in Russia, but the place where he was educated and where his worldview and opinions were shaped was Bielsk. Were he alive today, he would have been about 75-80 years old.

When the war broke out and Poland was occupied, he was in Bialystok and stayed there until 1941, the year of the outbreak of the Russo-German War. With the outbreak of this war, Levartovski fled to the Russian provinces.

In 1941, the Russians began to reorganize the communist underground in Poland, which after the reorganization was called the PPR. (Polski Partia Robotanica – Polish Workers' Party). At the beginning of this reorganization, Levartovski was parachuted by a Soviet military plane to Warsaw, where he began to reorganize the communist underground, primarily in the Jewish Quarter and after this in the ghetto. In 1941, negotiations began on the establishment of a Jewish fighting military organization, with the participation of the Communists, the Bund [another Jewish socialist political movement] and others; among whose participants was also Anatek Zuckermann[6], and at that time Levartovski represented in the negotiations, the Jewish communist organizations in Warsaw and in the ghetto, but in 1942 his tracks were lost.

To this day, the Polish press writes about him at every opportunity. Apparently, he was caught, imprisoned, severely tortured and executed. His wife and son remained in Poland. There he is greatly admired and held as one of the founders of the communist underground and the new Communist Party there.

Translator's endnotes:

Translator's footnotes:

Translated by Ronen Gilinsky

One of the more interesting types [of people] in Bielsk was Simcha Bagan. He was a young man who “went his own way,” distinct, so to speak, from the public, when we're speaking about what was called his spiritual world. Something within him told him to devote himself to the Jewish sound. He was not a musician and certainly not a conventional musician, but his soul was playing in a language of musical notes and was not able to be without it. Amidst the atmosphere of melancholy and shame, the worry and anxiety about what was coming to Bielsk, there was Simcha Bagan walking and humming to himself songs and melodies in which the pain of the nation, its identity and hopes, would come to him, and he would shudder and groan for them. It was as if he did not belong to Bielsk and to the increasingly narrow and shrinking horizon ahead.

Simcha knew most of the songs that were being sung by the nation in Yiddish. At that time, a period of seething anger in the Russian Empire of 1882-1905, the people were beginning a popular rebellion against both national and class subjugation. And all of that was reflected in the songs of the people and classes, which were splitting and bursting forth from the throats of concerned parties, and which had the common denominator of rebelliousness, rage, and sensitivity. These songs broke out by themselves among the Jewish nation as well, as expressed by Morris Rosenfeld,[1] Winchevski,[2] Raisen and others in songs for hundreds and in powerful poetry, tune and word. Simcha knew all of them almost by heart, text and musical notes, and his entire soul was filled to the brim with them.

That very same era was also a special period of time in the rebirth of the nation - the Bilu'im,[3] the Second Aliyah[4] at its beginnings; the Jewish Yishuv[5] in The Land [of Israel] that was awakening and making itself heard in the sounds of Zion, yearning for her and for gathering the nation into it. All of these were spreading and were being sung in a large variety of notes of song, the sounds making up numerous inspirational tunes. These songs, from “B'Machrashti,”[6] “Seu Ziona,”[7] “Shoshana Chakhlilat Einayim”[8] in Hebrew to the poems of longing of the Hebrew poets of the Middle Ages, had different meanings from Yiddish songs in that all of them were about nationalism and nature, a homeland and a past renewed. These Simcha Bagan also collected in his soul, and his soul melted over their sounds day and night, hour after hour.

He was a neighbor who lived next to my grandfather, in one of the huts that he rented out. And I would listen to the man, becoming filled with longing like him, and together with him I would become immersed in a world where all is good, where the whole world is forecasted for fulfillment, where everything is far away from this world of ours - the gloomy, heavy and materialistic world that had consumed me to the point of fear and depression. It is hard to express how grateful and thankful I was for him.

When I left Bielsk, Simcha Bagan was still single, lacking work and very often at the threshold of his poor mother's house, and living a life of stress and poverty. But in all of this, I never saw him embittered, lowering himself to the level of cursing the world or going into a silent rage that would be a disaster for him and for others. Just the opposite, in hours and days such as those, Simcha would dive into the sea of rich Jewish sound, bringing out of it all kinds of heart-wrenching melodies of longing in a chain of song.

What began with Jewish folk songs did not stop for hours until they arrived at the edges of the deepest level. And then his little room was filled with the highest emotions, an uplifted man, his soul enriched and humming.

More than once, I was reminded of Simcha Bagan and wondered about the richness of the variety of his vocal sounds

[Page 213]

and speech that was preserved and stored in it. From where did he get this strength to compress within his heart so many [deeply felt] expressions of yearning and soulful experiences from above and still remain as one of the people of Bielsk? Together with this, it is heartbreaking that such strength would be wasted on small worries of the day without leaving a memory of the treasure that was stored within him. I am sure that if Simcha had lived in a different public-setting, someone would already have “discovered” him and preserved him as a living encyclopedia of Jewish folklore, as he reflected in the speech and sound of his era of many difficulties, of uncertainty, upheavals and suffering.

Upon the death of Simcha Bagan, or more correctly, with his disappearance from my world, a tomb of forgetfulness came down upon me, causing me to forget the treasure trove of the people's knowledge which no institution in our nation has succeeded in preserving for the future. And I have lost a multi-colored source of expression of a rich soul.

In distant remembrances of my memories of Bielsk, Simcha's musical personality and talents stand out as something rare that is not common in our lives. He was the kind of person with a rich soul and like an expression that is difficult not to be remembered and to be mentioned.

Translator's and Editor's notes::

Translated by Nancy Schoenburg

He was wretchedly poor. One of the children of bitterly poor people. It is doubtful whether he had completed elementary school, that is to say, whether he had been allowed any years to devote to learning. While his family was in need of every grush [small coin of little value, like a penny] that the boy could bring home as compensation for the time that his labors took up, it was compensation for his time spent doing errands, services and other usefulness that the boy could derive from selling his strength in Bielsk.

It is almost certain that he was not studying, except for a few of his early childhood years. I remember him as always distanced from children his age, from the things they were busy with, from their merriment, their studies and games. He was immersed in and busy with various errands for his parents and, per the request of his parents, for others. And here, despite all that, Binyamin grew suddenly, matured. And here he was a youth, a young man speaking languages and seasoning his speech with quotations in languages and literary issues of nations and the treasures of their philosophy. Where did Binyamin get all this? No one knew and none of us had sensed it.

Anyway, when I remember him now, I see before me a small grocery store, happiness remaining in it hour upon hour, in helping his father most of the hours of the day, while the small children born to his father by two wives were at home waiting for their piece of bread. [The children were] from the first wife, Binyamin's mother, and the second whom he married after her death. But when evening would arrive, Binyamin would disappear, shutting himself up in various places and occupying himself diligently reading and studying. You would not see that in a regular person. This is how Binyamin came to learn Hebrew perfectly and how he succeeded in absorbing rich literary treasures from many generations. This is also how he suddenly appeared as a young man entering into conversations in Polish, in Russian, and German with all of them spoken fluently and the literature of each one of them given to him by himself.

Binyamin was thin and gave a poor appearance. His outward impression was so unremarkable, that

[Page 214]

it would seem to you that he was totally boring and forgettable, not worthy of attention. However, when he opened his mouth and began to converse, you would not be able to tear yourself away from him, and all the sources of his language [all the words he spoke] were engraved in your heart as something thrilling; you were not able to separate from him.

We could sit for hours listening to what Binyamin was relating. This was a small, thin fellow who did not belong to any party, movement or society. He never had time to make personal connections and to be integrated into any social framework. He was the center; around him people created a frame of keen attentiveness, listening, for the time available, just by the force of his rich personality.

Binyamin was as well-versed in Hebrew literature as he was in Yiddish and its literature, and just as he knew the foreign literature that they needed to hear. His “autodidactic” [self-taught] talent and his enormous perseverance were astonishing. His way of life, his grey existence, and the living conditions that surrounded him, did not give him an impetus for knowledge and the richness of understanding. Of his own accord, from his personal strength, Binyamin was pushed to treasures of thought and the idea of human society. From some inner drive in his soul Binyamin drew great investigative power and became who he was. And to this day, I am not able to explain to myself why and how Binyamin followed and searched again and again and revealed to himself horizons far beyond his own life and the lives of all those surrounding him.

There are people who know how to create, to sing, to tell and put together words of literature and articulate poetry and action. Binyamin abandoned all of these, although to this day I am not sure that if he had continued he would have become a creator, an author, thinker and speaker on many things important to man. He did not do that; he was not able in the reality of his life to think about composing in print for perpetuity, but there was something more within him than that. Binyamin himself was a wonderful creation and his life was nothing but a consistent and continuing expression of the human need to investigate, to know, to deepen, to encompass. In this Binyamin was something special in the world of mankind, and in the world of Bielsk he was a rather unique man who is difficult to forget.

Editor's note

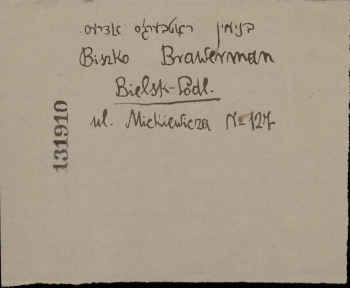

In the book An Unchosen People by Kenneth B. Moss (Harvard University Press, 2021), I read about a young man from Bielsk Podlaski who wrote under the pseudonym Binyomen Rotberg. The book explores the cultural and political environment in the shtetls of Europe during the escalating antisemitism of the interwar period. Central to the book are two works by Rotberg: an autobiography written in response to a 1934 contest organized by YIVO's Max Weinreich, and Rotberg's response to Weinreich's subsequent analysis of the submitted autobiographies. In his response, Rotberg concurred with Weinreich's assessment that “every Jewish young person feels himself to be without a future” in Poland because of their dire situation.The description of Binyamin Bushka-Braverman reminded me of what I read about Binyomen Rotberg. Was Rotberg's real name Braverman? To look for more information, I visited the website of the Center for Jewish History (of which YIVO is a part) to examine scans of his works. While scrolling through one of the PDF files, I came across a handwritten card that says in Yiddish “Binyomen Rotberg's Collection.” Below this, in English, it reads “Biszko Brawermen, Bielsk-Podl.,” with the street address “ul Mickiewieze No. 127.”

|

I emailed Kenneth Moss to inquire if he had identified Binyomen Rotberg as Binyamin Bushka-Braverman. In his response, Moss copied Dr. Rona Yona and Dr. Kamil Kijek, scholars who had previously worked with him and researched this question. Kijek stated that prior research had determined with 99% probability that Binyomen Rotberg was indeed Binyamin Bushka-Braverman, but finding this card served as conclusive proof. Both he and Yona explained that the information on the card would have been submitted by Rotberg/Braverman himself. Participants in the YIVO contest were required to provide their true identity in a sealed envelope so they could be contacted if they won a prize.A subsequent search turned up a postcard in another file. It was sent to YIVO with the same return address as above on the front and signed on the back in Yiddish as “Binyomin Rotberg (B. Braverman).”

|

Braverman's fate remains unknown. No record of his death or survival have been found, and this biography makes no mention of a life after Bielsk.The last paragraph states that he was not able to leave a lasting legacy, but the enduring significance of Braverman's written works is evident in their continued use and relevance nine decades later. His work, and on a larger scale An Unchosen People, speaks not only of antisemitism, but of dramatically conflicting Jewish responses to it. They included competing ideas of Zionism vs. Diasporism as an answer to the question of the future of Jews in Poland.

Understanding this period of time, and its similarities to the global wave of antisemitism facing us today, might help us make decisions and take actions necessary for a better future.

Andrew Blumberg

December 12, 2024

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 30 Jan 2025 by LA