|

|

[Page 399]

by M.Y. Fajgenbaum

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The war that broke out between Poland and Germany on the 1st of September 1939 bloodily burst into Biala on the first day. The first bombs from the German airplanes fell on Wolya [a suburb of Biala] on Friday morning; they were targeted at the airplane factory there. Simultaneously, bombs also fell on civilian houses, and among them, a Jewish house in which the entire family of the cabinetmaker Avraham Tajtlbaum perished.

The population witnessed the disorganization and chaos that ruled in all areas on the first day of the war. The airplane factory was almost undefended and no Polish airplanes were seen that would disrupt the German air assaults. However, it was hoped that this was only the beginning and that a radical change would come quickly.

There was no sign of the Polish government, which had trumpeted for the war by bragging that they were “united, strong and ready.” The chaos and disorganization increased from day to day. The German bombers flew freely across the Biala sky and sowed devastation. The population lay in the fields throughout the day and when the German bombers ceased their work at night, the population began moving and, first of all, buried the victims of the day.

The airplane factory already lay in ruins for a long time; there were almost no more Polish military in the city. However, the German bombers did not stop their rampage. Among the destroyed houses were: the magnificent house of Hartglas (burned and later taken over by the Germans), the Folks-shul [public school] at Grabanower Street (Motl Weine's house), Shimeon Lichtensztajn's house at Brisker Street, Papinska's house at Janower Street and so on.

Erev [eve of] Rosh Hashanah, several German tanks entered the city and while shooting went through Brisker Street in the direction of the Brisker highway. A Polish officer and a small group of soldiers opened fire on the tanks at the new market. As a result of the fight the majority of stalls at the new market were burned.

The Polish Republic ceased to exist after two weeks of war. The idea of life under German rule, threw the Jews into a desperate mood. Meanwhile, Biala was not occupied and remained “no-man's land.”

On one desperate day, hope suddenly began to glimmer for the Biala Jews that the Russian Army was marching west because, in accord with the German-Russian Pact, the Russian Army would occupy the Polish area to the Wisła [Vistula]. That is, Biala would belong to Russia.

The news actually was confirmed. The Russian Army occupied Biala on the 26th of September 1939, moving further west.

The holiday of Sukkous [Feast of Tabernacles] was celebrated by the Biala Jews with mixed feelings. They were happy that they had not fallen into the hands of the Germans, but they were haunted by an unease about the future.

The Soviet regime did not rush to bring order to the city; a certain restraint on their part was noticed; they left the initiative in the hands of the population. Various committees arose in which Christians were exclusively represented. Meanwhile, Jews avoided any cooperation with the new regime, remembering well the bitter experience of 1920.

The shops were closed more than they were open. The lack of raw materials was felt immediately and an exchange of goods among the population began. Long lines of buyers filled the open shops and bought everything they saw.

The Biala Jews were not destined to celebrate the holiday. At the end of September, the radio news reported that the boundary between Germany and Russia would be the Bug River and not the Wisła. The news spread in the city lightning fast and threw terror into the Jewish population.

[Page 400]

Although the Russian military personnel denied the news about withdrawing in conversations with the population, we began to notice signs of their withdrawal to the east: they began to remove from the city everything that was valuable in their eyes and load it on trucks. During this activity, they did not even treat with respect the Jewish hospital, from which they removed valuable medicine, equipment and instruments.

For the Jewish population, the question actually became whether to leave the city and go to the other side of the Bug [River]. This was possible because the Russian regime did not disrupt the exodus to the former Polish eastern areas. However, the Biala Jews had had bitter ordeals in this area during the First World War and in the year 1920. Then, during the era of transition, the Jewish population suffered with fear, but those who left suffered greatly in unfamiliar areas. Understand that no one then, even in their fantasy, imagined the terrible end that Germany would bring to the Jewish population. They anticipated a difficult life, but when had the Polish Jew had an easy life?

They knew that life under the Soviet regime was not easy. Everyone lived with the hope that the war would not last long; it would end with Germany's defeat and they would find themselves in a freer and more open world. However, those who went to Russia would first of all be transformed into a large group of refugees that was immediately exposed to suffering. The strongest were afraid of the idea of being hermetically sealed within the borders of Soviet Russia from which they could not leave after the war. However, those who decided to leave the city had one answer: “We do not want to be with the Germans and, particularly, not with the Hitler Germans.” It is estimated that 500-600 Jews left, the majority men who left their families in the city because it was assumed that the German persecutions would mainly be turned against the men.

Jews from all strata left for Russia. The majority of them had never had any connection with communism. A number of Jews remained in the city who qualified as sympathizers of the Soviet regime.

We cannot have any complaints against the Biala Jews as to why they did not leave their birth city for Soviet Russia because if Jewish leaders of the largest Jewish world organizations did not know of Hitler's plans of annihilation in regard to the Jews, how should shtetl Jews have known?

The End of 1939

On the 10th of October 1939, the Russian Army left the city and the German Army arrived in its place; this threw great fear on the Jews so that many who could not decide to leave the city earlier now did so.

Several hours after their arrival, the Germans took Jewish hostages (using a list provided to them by the mayor). Christians wearing white armbands appeared in the street and their first task was to grab Jews for work. The Germans had no lack of work and the Poles again zealously provided more Jews, even more than had been requested.

The German regime immediately ordered the opening of the shops and endeavored to have the city return to its normal appearance, which actually happened over the course of several days. A curfew was brought in that lasted until the Germans left the city. The Jewish population had less free time to move in the streets than the Christian population.

|

|

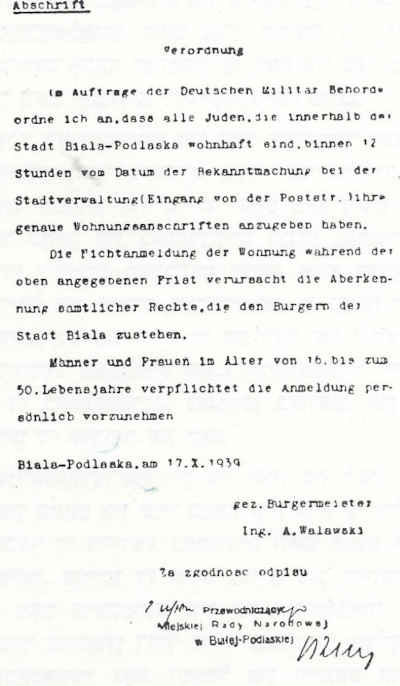

| Order for the Biala Jews to report their addresses to the city hall |

Meanwhile, the managing committee of the city was in the hands of the military regime and it appeared that they still did not have any anti-Jewish instructions.

[Page 401]

So, the regime gave Jews permission for trips to Warsaw and Lodz, for which Jews left and began to bring back various goods. The trade blossomed. Freed from the heavy chains of the Polish finance regime, the Jews breathed more freely, forgetting

|

|

| Prohibition against leaving the city |

where there were. However, the bustle of trade lasted a very short time because in November 1939, the well-known Gestapo entered Biala and a long-lasting era on a road of suffering and terrifying death began for the Jews.

The Gestapo was quartered in the chateau of the Raabes factory on the Wolya. Its first contact with the Jewish population was the demand for a monetary payment of several tens of thousands of zlotes. In order to force the payment to be paid quickly, the Gestapo arrested a number of Jews and threw them in prison where they were continually tortured. The Jews were freed from prison after the payment of the appropriate sum.

The appearance of the members of the Gestapo in the street brought panic to the Jews and they would run from the street. The printing press owner, Avraham Lubelczik, hearing that the Gestapo was coming to him, had a heart attack and fell on the spot.

The Gestapo found the shamas [synagogue caretaker], Yoal Gringlos, who stood forlorn in his talis [prayer shawl] and tefilin [phylacteries] in the house of prayer; they led him out to the street, brought several Jews with a ladder, on which the shamas had to sit in his talis and tefilin and the Jews placed the ladder with the shamas on their shoulders and had to go through the streets of the city.

The arrival of the Gestapo caused several dozen Jews to run from the city. This time, however, it was difficult to smuggle oneself across the border because it already was well guarded. Among those escaping was the Biala Rabbi, Rebbe Zvi Hirszhorn.

Every Jew who encountered the brown [shirt] murderers on the road would be murderously beaten. They robbed the goods from the Jewish shops, even taking the money from the cash drawer.

The economic life of the Jews was paralyzed. The Germans actively undertook the liquidation of Jewish positions. The large Jewish businesses were requisitioned; the goods were taken out to trucks and the owners were thrown in prison, demanding high payments from them. The workshops and the tools were taken away from the Jewish artisans.

A number of Jewish merchants, wanting to save their existence, gave their businesses to Christian acquaintances, assuring themselves with various agreements. A very small number of these Christians kept the agreement, but the larger number of them immediately tried to get rid of the Jews. Understand, this was not difficult to accomplish because the Jew already was without rights and helpless.

In November 1939, the Gestapo Commissar, Hildeman,[a] ordered that every Jew, starting at age six, from the 1st of December 1939 must wear a yellow Mogen-Dovid [Shield of David – Jewish Star] of 15 centimeters [almost six inches] on the left side of their chest. The sign of disrepute was later traded for a white armband with a blue Mogen-Dovid that had to be worn on the right arm. Jews were forbidden to leave the city without the permission of the German regime.

One day, all of the former members of the last-elected kehile authority [organized Jewish community] were called to the Gestapo. The former dozores [members of the Jewish community council] were ordered to immediately organize a Judenrat [Jewish council].

[Page 402]

Other members who previously did not belong to the who previously did not belong to the kehile were attracted to the Judenrat. The Judenrat officiated at the premises of the kehile at Brisker Street.

Then the Germans had an address to which to turn with all of their demands. The Judenrat would constantly receive orders for various goods, which reached high sums of money that had to be covered by the Jewish population. Orders for hundreds of Jewish workers would be sent to the Judenrat and understand that the workers were not paid for their work, but very often they would be beaten while working. The Judenrat had to organize a labor office so that it was able to provide the demanded number of workers every day. The Judenrat had to pay a number of the workers for their work because they simply did not have the means to live.

The occupying regime quickly assumed the entire state apparatus and the former Polish officials helped them a great deal. These officials let out on the Jews their entire rage at Poland's defeat. Where they had the opportunity, they let the Jews feel it.

The tax office quickly became active again and it began to demand all of the ordered taxes from the Jews. The officials Gerech and Kunicki particularly excelled at this. If a Jew did not pay the tax debt quickly, he was thrown in prison and tortured there.

The Pole Bielecki, who went around every day requisitioning Jewish residences for the Christians whose previous apartments were suddenly too crowded, dealt with the establishment of the housing office. Christians heartily helped the Germans in clearing out the furniture from the Jewish houses; Cibulski, the prison guard, particularly distinguished himself in this.

Every Pole who held the office, who had a connection to Jews and where the representative of the Judenrat took care of various matters, asked for gifts from the Jews just like the Germans. Their requests had to be met. In this area, it was particularly good to fill [the requests of] the mayor Antoni Walawski, his aide, Szczepan Szczepanski and the above-mentioned official from the housing office, Bielecki.

In the ranks of these Christians were found the early initiators and inspirations for imprisoning the Jews in a ghetto and this was a smaller one.

Jews from Suwałki and Serock were brought to Biala at the end of 1939. These Jews were gathered in the middle of the markets in their cities and as they stood, they were taken out of their cities in the Lublin Województwo [administrative district]. The Jews were not permitted to take anything with them and from the market they were driven into the train wagons. We learned from the Jews what kind of inhuman torturing they had already gone through during the few months of German rule.

Two thousand refugees were brought to Biala, of which the Jewish population took a large number into their residences; a very large number were quartered in the synagogue, houses of prayer and Hasidic shtiblekh [one room synagogues]; and a number of refugees left for Warsaw and other cities.

The Year 1940

At the beginning of 1940, Jewish prisoners of war from the former Polish Army who were from the former Polish eastern districts were brought to Biala.

The road that led the prisoners of war to Biala was marked with a bloody harvest [of bodies] and with the graves of their comrades. The imprisoned were brought from Germany to Lublin and from there, on a frosty day, they began to drive them on foot from there to Biala. On the road, the German escorts made the ranks of the prisoners more sparce by firing on them with automatic weapons. The prisoners of war were interned in Poczice's barracks on the Brisker highway.

In these barracks, the Stormists [Sturmabteilung – Stormtroopers] began to build a camp with the help of the Jewish workers whom the Judenrat would provide there every day. The mayor, Walawski, decided to inform the Jews that this camp was being built for the Biala Jews, where they would be driven at the beginning of April. Such news, understand, brought despair and dismay among the Jews.

The prison was full of Jews, who were truly harassed. Who was not in prison then? One as a payment, another for taxes; merchants for not willing to say where they had ostensibly hidden their goods; artisans for not willing to show their hiding places for goods that they had ostensibly made. In connection with uncovering hidden goods, they brought from Lublin to the jail the Biala

[Page 403]

merchants Yosef Gitlman, Fishl Wlos and Moshe Yitzhak Biderman.

Jews began to work sometimes at forced labor and received a salary of two zlotes a day, which was not enough on which to live.

Oprowizatsia-kartn [ration cards] were implemented, from which the Jewish population would receive almost nothing. A portion of the population found a solution; they traded illegally, looking for income wherever they could. Although it was forbidden for Jews to travel on the trains, Jews would take the risk of a trip on the train to Warsaw. They would dress like Christians and bring goods from Warsaw.

Several shops were open during the day, but since they did not receive anything officially, what were they permitted to sell? However, the trusted customer could receive everything.

Edicts were constantly harming the Jews. The last Jewish economic positions were liquidated by the Germans. Even the small Jewish shops were closed and the goods were taken from them. Several Jewish shops remained on Grabanower Street, where the owners were changed each time by the regime. The smallest shop had a sign with a large Mogen Dovid that was bought at the administrative district for a large payment.

At the entrance to Grabanower Street from the market and from Prosta Street, two large linen banners were hung with the inscription: “Plague – Danger! Entry is forbidden for Aryans.” Jews were forbidden to set foot on the Wolnoszczni Square (market).

With the Jews forbidden to appear at Wolnoszczni Square, it became difficult to approach the post office. In addition, the Jews had, in general, no desire to stand in a line at the post office and be exposed to various harassments. Therefore, the Judenrat made great efforts that it be allowed to organize a post office division. The efforts succeeded and a post office division arose at the Judenrat where there also was a telephone. Every day two Judenrat members would go to the German post office and there take care of the postal matters for the Jewish population.

On the eve of the Days of Awe, the Wolya Jews were ordered to enter the city and Wolya was cleared of Jews.

Jews were forbidden to use their balconies. If the balconies were made of metal, they [the balconies] were taken, along with all of the metal that the Jews had and

|

|

| Prosta Street. A sign on Hershl Sznajman's house with the inscription: “Jewish quarter” [Photographed winter 1944/45] |

given to the regime (Poles had to provide only three kilos [6.6 pounds] of metal).

The situation in the synagogue and in the houses of prayer to which the homeless Jews had been brought was sad. They lived in terrible conditions. They particularly strongly felt the cold winter. Every crumb of wood in houses of prayer disappeared. The refugees tore out the floors, took down the double windows; the fences in the Jewish quarter disappeared and even the trees at the cemetery; everything was devoured in the fires at which the refugees tried to warm their limbs.

We were very satisfied that the cold winter day quickly left and the long night ended.

[Page 404]

We would board ourselves up in the houses, where we told the news of the day and waited for the defeat of the Germans.

Although the border between Germany and Russia was heavily guarded, several Bialers succeeded in smuggling themselves across to the Russian side. We learned from them that a large number of Bialers refugees wanted to return home because the life of a refugee became tiresome, particularly as they heard there [in Russia] that the Jews on the German side were living and it was not bad economically.

In May 1940, a train arrived in Biala with those repatriated from the Russian side and among them were many Biala Jews. Those returning were truly surprised by the good behavior toward them on the part of the Germans.

In the course of the decisive battles in western Europe, the Germans did not forget the Jews and they were reminded that Germany was victorious.

On a beautiful morning, the Biala Judenrat was called to the Gestapo. There the Jewish councilmen were arranged in a row and the Gestapo man Kot read the news from a German newspaper that a Weizmann Legion to fight against Germany had been created in Eretz Yisroel. Therefore, a Jewish land would be created there with the English king at the head. After reading the notice, Gestapo members with sticks entered the room and severely beat the Jewish councilmen.

In March 1940, the Jews were ordered to register for forced labor. Many of the Jews tried to obtain certificates from doctors that they were not capable of working and placed the certificates with the Judenrat.

In June 1940, the sad chapter of forced labor began for the Jews. Jews from Mezritch [Międzyrzec] were brought to Biala and, later, also from other cities. The camp at Piczic's, at the barracks was full of Jewish workers. The Jews were employed with repair work and lived in the camp in the most terrible conditions. The Biala Jews were spared. A very small number of them worked at the repair work in the city itself. Every day, after the work, they would return home. The majority of the Biala population had

|

|

| Notice forbidding the use of balconies |

[Page 405]

made provisions for workplaces that were recognized as forced labor by the regime.

The repair work was carried out under the leadership of the German engineer, Grinenfeld, who had his headquarters [in Biala]. The work suppliers and guards for the workers were Stormists, with their aides – the volks-Deutschen [ethnic Germans].

Jews did not intend to suffer in the camps and began to look for ways to find their way out of them. They did not have to look for long because every German had already found a Jewish go-between who was occupied with freeing Jews from the camps and a trade of slaves from the camp began. Understand, that not everyone was able to pay such a ransom price, so the poor remained in the camps until deep autumn.

On one hand, the Stormists freed Jews from the camps for a fat reward, but on the other hand, wanting to erase the traces of this commerce, they tried to maintain a strong regimen both at work and in the camps. One day, the Stormists guard went to the meadow and, for no reason, shot several Jewish workers from Mezritch.

On a July morning in 1940, the Jewish population was surprised by an extensive search for the men. From all sides [of the city], Jewish men were led in the direction of the barracks at Artilerisker Street. It gave the impression that they planned to take away all of the Jewish men from the city. The women experienced hours of shock and could not even move because it was still early and because the curfew forbid going out in the street.

When all of the men were assembled at the large pit at the 9th Pulk [regiment], the Germans went to work: carrying out a selection among those assembled. They examined every work card and decided: home or remain on the spot. The majority were freed and those held were led away to a train and from there in an unknown direction.

As on the same night, similar searches were carried out in most of the cities in Lublin administrative district, it was quickly learned that those held had been taken to Belzec for forced labor.

The Biala Judenrat spared no effort to extract the Bialers from Belzec. However, this succeeded only after a certain time. Among the Jewish victims who fell there during the work was the Biala young man, Motl Hafer.

Autumn time 1940, the Judenrat was freed of the burden of providing workers because a labor office was created that was occupied with this matter.

|

|

| Order to deliver up all mealses |

[Page 406]

|

|

| Announcement to register for compulsory work |

Working as officials at the labor office were the Jews: Emil Wajnberger, Tuchsznajder, Edek Slobodzki (from Warsaw), Doba Krajzlman, Lewi (a son of Yitzhak Lewi), Chrielewski, Cymerman (from Sulwalk) and a young woman from Serock. Although the officials were sent by the Judenrat, from whom they would receive their salary, the Judenrat had a very weak influence on them. The official Slobodzki particularly made use of his office, and extracted a great deal of money from the Jews.

The volks-Deutsch, Leman, a former worker at the municipal airplane factory, ran the labor office, which was designed only for Jews. Jews would say of him that he was a fair “gentile.” His “goodness” consisted in that he took money from the Jews and this already was a good trait. He did not turn over any Jewish workers who had transgressed to the Gestapo or to the Nazi sondergericht [special court] only he alone would teach a lesson on the spot. He often battered Jewish workers until they were bloody. Jews accepted this as love, rather than falling into the paws of the Gestapo. Very often, Leman beat Jews without any reason, but Jews explained it as being a result of his nervousness and with wanting to show that the labor office was a true Nazi office.

There was an instance when several young Jewish men were transferred to the Gestapo for not reporting for work punctually and the sondergericht sentenced them to a year in prison. Among those sentenced was the young man, Ziglman, from Garncarsker Street.

Later, the labor office did not have to strain to force the Jewish workers to work. But the opposite, the Jews themselves demanded employment from the labor office because they needed to have a few zlotes that could be earned while working. They also did not want to appear jobless to the Germans. In particular, after all of the hard labor conditions, the situation became more favorable than in a labor camp. After an entire day of work and after all of the blows received at work, in the evening they came home and had a warm environment.

At the time, they began to pay the Jewish workers for their work. A worker would earn about 3-4 zlotes a day. The Jewish workers would do piece-work in the carpentry factory and earn approximately 10 zlotes a day. The Christian workers who also worked there could not produce such earning. Every night the Jewish carpenters would bring sacks of wood from the work and sell it in the Jewish quarter. The price of bread, in comparison to other articles, was still cheaper (from 75 groshn to one zlote a kilogram).

The Jews were mainly employed by the military and by German firms that carried out various work for the military. Among those firms were: Benz, Maier, Zager-Werner, Stuag and Zid.

The firms Benz, Maier and Zager-Werner carried out their work at the airfield. The remuneration from the firms was little, but the workers would receive plentiful blows. The Benz firm particularly excelled in the area of beating Jews. The leader of the labor office, Leman, would send Jews to the firm who to him had sinned.

At the Zid firm, the Jews were employed in erecting barracks for the security police at the Janower

[Page 407]

highway. The reward here also was weak and there was no lack of blows.

The Jews were employed repairing the highways by the Stuag firm. The work was difficult and terrible. The workers would pave the highway with heated tar, which would emit gases that would burn their faces. For this work, the Jewish workers were not given any means of protection and a very large percentage of them would be brought to the Jewish hospital in serious condition.

Jews also worked in the large enterprises that belonged to the volks-Deutschen and to the Poles, such as: in the sawmill and the carpentry shop of Zawidzki that was located in Hercl Czarne's sawmill and the Raabes factory; in the carpentry shop of Hauschild, that was located in Piczic's sawmill.

Summer 1940, when they began to take Jews for forced labor and send them to labor camps, a group of Biala Jews wanting to assure themselves of a workplace to avoid forced labor erected a brush factory at Garncarsker Street under the leadership of the Mezritch tradesman, Munye Sucharczik. At the beginning, the Judenrat led the factory, but it was soon taken over by the German, Wanczura, a brother-in-law of the vice district administrator, Fritsh.

This German Wanczura also took over the soap factory of Sura Gele Goldfeder at the Wolya and turned it into a large enterprise. The professional leadership was found in the hands of the Jewish refugee, Bibrowski, and his helper was Volvish (Volf) Wajcman. This enterprise was not really for the Germans; he requisitioned both Jewish printers, Lubelczik's and Hochman's, and erected a large printing plant at Pulsudski Street.

The Biala Jews had “equal rights” in the area of work and even received “state posts.” Thus the Jews worked in the administrative district and other German offices, such as: messengers, mechanics, drivers. Who even speaks of military workplaces? There, they literally could not go without Jews.

Despite the fact that the labor office provided Jewish workers for all German workplaces, they would still grab Jews for work from the street. There were Germans who could not give up the pleasure of walking through the streets and chasing after Jews. These Germans, in general, did not need to have Jews to work, only to bully them.

The Year 1941

At the beginning of 1941, the Germans arranged an expulsion rehearsal in the city. On a winter morning, the gendarmerie and the security police went through the city, grabbed a few old Jewish people, women and men, and took them to the village of Opole, near Rososz. Several days later, all of those taken out came back. It was difficult to understand what the Germans intended with this.

War illness – typhus – spread widely in the Jewish quarter. It reigned in the Jewish houses where there was crowdedness and where they lived under difficult hygienic conditions. The courtyards also were polluted because their sanitary facilities were not suitable for such a large number of residents. The sanitation division at the Judenrat could not catch up with the cleaning.

The Biala Judenrat also had the Jewish hospital, which was over-crowded, under its control. At the beginning of the German occupation, in general, there were no Jewish doctors in the city and the Jewish sick were forbidden to see Christian doctors.

Summer 1940, Jewish doctors came to Biala: Dr. Bergman (is supposed to have come from Katowice), Dr. Hochman (a refugee from Germany, came from Warsaw) and Dr. Rubinsztajn (came from Warsaw). In 1941, the Warsaw surgeon, Dr. Gelbfisz, came to Biala. The feldshers [traditional barber-surgeons] Chaim Musawicz (the Kabriner) and Berish Wajsman (from Łomazy) were active.

A help-committee existed at the Judenrat under the name, Jewish Social Self-help that would also receive subsidies from the Jewish regional help-committee in Lublin. At the head of the committee was Moshe Rodzinek. The committee endeavored to ease the need of the poor by distributing lunches and distributing medical help without cost. However, the financial means of the committee were too small to be able to free the need on the Jewish streets. The committee was located at Grabanower Street in the house of Yakov Kornblum. The committee kitchen was active in the former bakery of Yitzhak Fogel on Prosta Street.

In spring 1941, the Germans began to rush to build military objects in Biala and its surroundings and mainly air bases. Jews were employed in all of the works and this time their conditions became more favorable in the work camps than a year earlier. It was clear to the population that Germans were preparing for a jump to the east.

[Page 408]

In the middle of the preparation for the war, a number of edicts against the Jews again were issued, of which we will here enumerate only a few of them.

Jews were forbidden to leave their residences. Christians were forbidden to permit Jews to enter their houses and, in general, have any contact with Jews. This was motivated by the fact that Jews were covered with lice and typhus would be spread through them.

Jews were forbidden to travel in coaches and by horse and wagons.

All Jewish immovable estates were confiscated and the Jews had to give the rent money to the guardianship that was organized for this purpose. Even the owners of the houses were obliged to pay rent for their apartments. The guardianship collected the rent regularly and the Jews had to remodel the apartments at their own expense and clean the streets and courtyards.

The confiscation law also was valid for the houses of prayer and the synagogue. As the homeless were living in the latter, the Judenrat had to pay rent for them. The Judenrat dared to subtract from the rent the expenses that were connected with cleaning the toilets near the synagogue. For such daring, the Judenrat representative, Yakov Ahron Rozenbaum, received a slap from a German comptroller, who had come specially from Lublin about this matter. However, the Judenrat was stubborn and again subtracted the expenses.

Among the fresh anti-Jewish edicts was an order to pay the Jewish workers 20 percent less than the Christian ones. The earnings of the Jewish workers decreased and the scarcity grew. A kilogram of bread now cost six zlotes and in time the price reached eight zlotes.

After Passover, the city was flooded by the German military, which kept on storming to the east. We saw that the last preparations for a new bloody struggle were ending. It was clear that it was the threshold of the war between Germany and Russia. This feeling of war evoked a hope from the city Jews that the war between Germany and Russia would speed up Hitler's end, although they trembled at the prospect of the fresh, bloody turmoil. Meanwhile, the prices on all goods rose sharply. The price of bread in those days reached 12 zlotes a kilogram.

Shabbos night, the 21st of June 1941, in the middle of the night, the German Army crossed the Russian border and began to push east. The hope of the Jews quickly faded away and the fear of the next day increased.

During the first weeks of the war between Germany and Russia, Russian prisoners of war would constantly be brought to Biala. The prisoners would ask for a piece of bread or matches when they were led through the streets. However, no one filled their requests because the Jews paid very dearly for a piece of bread.

|

|

| Announcement about petechial typhus illnesses that mainly spread among Jews |

[Page 409]

Moshe Ganski and Akiva Jurberg, arrested for offering a piece of bread to the imprisoned, were transported to the Auschwitz camp where they perished. The Polish Biernacka was arrested for the same sin, but they succeeded in extracting her from the Nazi talons.

The Russian war prisoners were terribly treated in German captivity. However, cruelty was the fate of the Jewish-Russian war prisoners. The German rulers made the greatest effort to find Jews among the prisoners and to annihilate them.

Once, when Biala Jews were working at repairing the Brisker highway, a freight train passed by with Russian war prisoners. Seeing the workers, they began to shout. Suddenly, one began to shout in Yiddish: “Comrades! We are being taken to be shot!” The Jewish workers recognized one of those shouting, the son of the shoemaker, Goldberg, from Janower Street.

In autumn, the so-called Jewish ordnungsdienst [ghetto police], who were provided with complete clothing and a hat on the pattern of the Warsaw ghetto, was organized by the Judenrat at the order of the administrative district. The task of the Jewish police consisted of: keeping order in the Jewish quarter, which was mainly expressed in not permitting walking on Grabanower Street, which was the central street in the quarter; providing to the labor office Jews who were in no hurry to go to work; watching over the sanitary conditions in the quarter. Later, when a “prison” was created at the Judenrat to hold arrested recalcitrant tax payers, the ordnungsdienst was busy with arresting the accused and with guarding the “prison” so that the Jews would not “run away.”

Yakov Goldsztajn (commandant), Hinekh Bialer, Asher Rozencwajg, Motl Finklsztajn, Moshe Preter, Chaim Fridman, Fishl Lebnberg, Yakov Tokarski, Lajbzon and Chonen (a saddlemaker from the Wolya) belonged to the ordnungsdient. The secretary was M. Hercman (former bookkeeper at the Raabes factory). After the commandant, Goldsztajn, was shot in the summer of 1942, the refugee from Sulwalk, Cymerman, was designated in his place.

In autumn, at the order of the regime, the office of the Judenrat was moved from Brisker Street to Yakov Kornblum's house on Grabanower Street. This was done with the intention of ousting the few Jews who lived outside the designated boundaries of the Jewish district.

On a November day, Thursday, the security police went to the Warszaw highway between Biala and Mezritch and shot every Jews they met. Among the murdered was the flour merchant, Berl Czelaza, of Grabanower Street. It seems this was because of the order that forbid Jews to leave the area in which they lived.

And how could the Jews remain sitting at home and watch how families were dying of hunger? They actually ignored the dangers and started on their way, where a bullet often reached them and they

|

|

| Confiscation of immovable property |

[Page 410]

never came home. Jewish houses drowned in the sadness and tears.

Christmas Eve, the representatives from the Judenrat were called to the district headquarters where they were given an order to collect all of the furs from the Jewish population. The Judenrat reported this order to the Jewish population and the office of the Judenrat was transformed into a fur camp. Not all of the Jews hurried to give their furs to the Germans and they burned or destroyed them in another way, although they were threatened with death.

A few days after the passage of the period to turn over the furs, the security police set out on a search of Jews. Men and women were stopped and they were taken to the security police. It was learned from the first freed Jews that the search by the security police was for Jewish furs. The search gave rise to a Jewish victim: the security police

|

|

| Prohibition on the use of horse drawn coaches |

found a fur under a coat of a Jew, probably someone abnormal, and he was shot.

Rumors reached Biala that the Jews in the occupied eastern area of the former Poland were being tortured and annihilated by the Nazis. And that among the victims were Biala Jews who had escaped from their homes in 1939 and considered themselves saved from the Nazi talons. We learned from Mrs. Sura Khohan, (née Preter), who returned from Slonim, about the frightening slaughter of the Jewish population that the Germans had carried out there. Among the murdered in the slaughter were several Bialers who had gone there in 1939, such as: Moshe Orlanski and his wife and child, Sura Khohan's husband and so on.

The city was full of German officials and they all were busy with the Jews. Woe to the Jew with whom these officials interested themselves.

A division of the S.D. [Sicherheitsdienst] (Security Service) was located on Pilsudski Street (Mezritcher), which the S.S. people, German and Glet, led. In addition to the gifts that the division would demand from the Judenrat, it also demanded reports from the Judenrat about what the Jewish population thought and said. The Judenrat did not hurry to provide such reports. Once, when the S.S. men were insistent in this matter, it was written in short that the Jewish population was full of concern about the oncoming winter, how to obtain potatoes, firewood and other needed things. The S.S. men, hearing such a report, entered a wild rage and began shouting: the Russians have taken back Minsk, Vilna and Riga; are the Jews talking about this? The members of the Judenrat were escorted out of the office with blows.

A volks-Deutsch named Apel was located at the Biala gendarmerie. This gendarme was surely a wagon driver for a Jew because he spoke Yiddish well, constantly adding small bits of wagon-driver curses. The Jews gave him the nickname, Yankl Morde [chin or snout]. This gendarme would apply pressure on the Jews and there was not a day on which he would not catch a Jew in a sin and batter him. If he found a piece of meat in a Jew's house, he would carry on a real pogrom in the room. He broke everything with an axe and threw it out through the window and then beat those in the house. When the Jewish shoemaker, Borukh Frajner, who was friendly with him, asked him: “Apel, what do you want from us?” He would answer: “May you know of cholera! With all of your bag and baggage, there is no end to you!”

[Page 411]

The Polish police przodownik [leader] Drwencki (came from Pomer), was active at the gendarmerie and he was a privileged person there because he spoke German. This Drwencki had his methods of blackmailing the Jews who he knew were involved in commerce. He was a constant visitor of the Jews, but it was difficult to satisfy his appetite by giving him the most beautiful and best. After everything, he would turn the Jew into the gendarmerie.

The Biala security police, who were housed at Grabanower Street, literally in the heart of the Jewish quarter, rampaged. Among them, those who stood out with their special cruelty were: one Peterson (nicknamed “blond murderer” by the Jews) and another, with a fat head, whom the Jews would call Psil [idol, graven image]. The security police had a forge at the new market and woe to a Jew who these two security policemen would take to the forge ostensibly to work. Such a person would remember his visit there for long weeks. When the two security policemen were noticed from afar, the street would empty of people.

The Biala security policemen would attack Jewish houses at night and rape the women there. After doing this disgraceful act, they would loot the residences.

A special militia was active at the administrative district, which consisted of volks-Deustchn and was called the sonderdienst [special services]. Their leader for a time was one Grzimek, who caused great problems for the Jews. The sonderdienst would come to the Jewish quarter to grab Jews for work and, in addition, they heavily beat them.

The agents of the Biala Criminal Police also exerted influence over the Jews. They knew which Jews were employed in trading and smuggling and they constantly blackmailed them, extracting giant sums and items of worth from them. The agents Constanti Baldiga, Wolanski and Golenbiowski excelled here. In addition to being a blackmailer, Baldiga also was a murderer. In the winter of 1941-42, he shot the first two Jews in the city, the carpenter, Wajsberg (the son of the carpenter Khanan) and a young man from the former Polish eastern sector.

The Polish police also constantly reminded the Jews of their existence. Here, too, the Jews stood with their pockets [wallets] and paid so that the Polish policeman would overlook [things] and stop bothering them. What Jews then were [considered] legal in regard to German law? What did a Jew still possess in his house after everything had been confiscated? And a Polish policeman knew very well where to look…

The officials at the Biala administrative district would constantly demand presents from the Judenrat, which reached great sums. Their conduct in relation to the Judenrat was cynical. They constantly assured them that no more edicts would come, but actually they themselves created and issued anti-Jewish orders. The Judenrat knew well the worth of their assurances.

Of all of the exterminators, the “most tolerable” for the individual Jew was the Gestapo. It did not grab Jews for work; it did not come into the Jewish quarter to beat Jews. It was in contact with the Judenrat, sending orders there for giant sums, extorting the last groshn from the Judenrat, which was constantly a debtor. Several Jewish artisans were swamped with work for the Gestapo. In time, the Gestapo arranged a tailoring workshop [in its facilities], where the brothers Nakhman and Yoal Zuberman, Meir Rajc and Ahron Wolkowicki customarily worked. The constant shoemakers for the Gestapo were Borukh Frajner and Nekhmia Dorfman. The materials were provided by the Judenrat.

These artisans from time to time would get a hint of news from the hangmen about Jews and confide it to a few chosen people in the quarter. They would know who had been brought to the Gestapo prison at the Raabes factory or who had been taken out to be shot in the Grabarker and Wulker forests.

One of the first Jewish arrestees at the Gestapo prison was the Biala resident, the apothecary, Michasz Hofer. The Gestapo probably did not know itself why they were holding him, but it did not want to free him. Hofer would be in the city the entire day, but he had to return to the prison to sleep. The members of the Gestapo extorted valuable items from Hofer and after many months they freed him from prison.

The Year 1942

Dejected, resigned and full of apathy, the Jewish population strode into the new year of 1942, which was the last year for them in their city of birth. The suffering before death was even more difficult and the rope around the neck was drawn even tighter.

On a winter night the Judenrat was informed that two young, Jewish men had been thrown into the cellar, where they had worked, by the security police. One of them was the son of Khanan Rajch. It was already known that there was the smell of death [associated with this]. The young people were supposed to have sawed a board there in order to take the wood home. This was

[Page 412]

noticed by a security policeman who threw them in the cellar. The Judenrat began its efforts to extract the two young men. The security police demanded a sum of 10,000 zlotes that even at that time was a very serious sum. Yet, the sum was collected and was given to the security police. However, only one young man was freed because in between Rajch had already been shot.

Every day, Christians would come and tell of the murdered Jews who lay outside the city. They had been shot by the Germans who saw them there. The record of the carrying out these executions comes from the gendarme, Leon Busch, a volks-Deutsch from the Poznan region.

Thus, the gendarme Busch shot two others at the Wolya, near the church, including Liptshe (Adlersztajn), the son of the [female] butcher. A few weeks later, the wife of Pinyele, the bagel baker from Mezritch Street, perished from one of his [Busch's] bullets at Szidorska Street.

During the first week after Passover, tens of Jews were arrested, mainly those who were once punished for violating the Nazi laws. After spending the night at the Polish police post, the Gestapo took them away on the Janower highway in the morning and shot them there, near the Jewish cemetery. Among those shot were: the butcher, Yudl Jurberg and Adlersztajn (his wife Tsvya), as well as the Sulwalker homeless one, Bernsztajn (a brother of the photographer, Osif Bernsztajn) and so on.

On a June evening, the Polish police carried out arrests among the Jewish population. That night, the arrestees were imprisoned in the Polish police post and, in the morning, they took them out to Wulker forest and shot them there. Among those shot this time were: Chaim Fridman (nickname Beznozek [without legs]), Nakhum Tenenbaum's son-in-law, and Yakov Goldsztajn, commandant of the Jewish ordnungsdienst, who was arrested the day before by the gendarmerie.

The young Moshe Lichtenbaum (Leibe Mednik's grandson] was among the arrested Jews at the Polish police post. He was arrested during the day because of a sharp answer he gave to a Christian who had insulted him. His parents, seeing the evening arrest, immediately understood that fresh executions were being prepared. They began to make efforts to save their child. It is easy to imagine the mood of the parents who had to return home at seven o'clock (the curfew time for the Jews) without their son. They went outside in the morning and learned that the Jews arrested the day before had actually been shot. However, their son remained at the Polish police post. They began to shake with joy. Moshe Lichtenbaum had been arrested by the ruddy security policeman Peterson who was known by the Jewish policeman, Moshe Preser. He asked the murderer for hours that he free Lichtenbaum, but he could not prevail on him. This Peterson, however, it appears, wanted the young man to go through a struggle with death and ordered the Polish police to come to take the Jews to the Gestapo, imprisoning Lichtenbaum in a separate cell. Thus, the young man and the Jews who had been shot went through their last suffering before their death, [Lichtenbaum] not suspecting that he would be saved. This Lichtenbaum said that it was clear to everyone that they were going to their death and they spent their last hours reciting the vide [confession of one's sins].

At the same time, a group of Janower Jews were shot in Wulker forest and among them the Biala resident, Leibl Rodzinek who had made efforts to free the Janower Jews. Rodzinek was also supposed to be helped by the Christian woman, Konopka, but instead of helping him, she handed him into the hands of the Gestapo.

There was a series of shootings. However, German cynicism went so far that they did not stop the court hearings against the murdered Jews. Thus, for example, there was a court hearing for leaving his place of residence for the Biala resident, Noakh Wajnsztajn (from the village of Proszeki), that took place in Lublin. At that time, he had been transferred from the Biala prison to Lublin. His two daughters did not rest and did everything to save their father. They engaged the well-known lawyer, Hafmakl-Ostrowski, who had access to the German courts and, therefore, they were asked to pay really legendary sums. The Jew was not present at the court hearing. With joy, his daughter heard the verdict freeing him and they waited impatiently every moment to see their father. However, there was nothing for them to await. As the lawyer told them, their father had been sent away to the east…

In the middle of the hardships, the Judenrat received an order from the administrative district official, Lipkow, to put together a list of candidates who wanted to travel to Eretz-Yisroel or America. The Judenrat did not issue placards about this announcement, but individuals learned of this and thought: be listed or not be listed. In the circles of the Judenrat this was treated with mistrust for the entire matter. They simply said:

[Page 413]

the Germans would not become involved with a Jewish exodus during the full fervor of the war. In general, the Jews did not strongly like to appear with their names on the list that were being provided to the Germans. And as long as the administrative district no longer applied pressure for the list, the Judenrat forgot about it.

The majority of the population lived from their work. A number of Jewish artisans still carried on with their workshops. On the other hand, the official merchants remained an insignificant percent of the employed. Twenty or 30 small shops were found in the Jewish quarter, mainly on Grabanower Street.

Naturally, smuggling occurred on a large scale in the Jewish quarter to obtain even more food. Jewish artisans would work for Germans and for the Christian population and from them they would receive various products. The Jewish workers would also bring various goods from their workplaces.

The main article smuggled was flour. This article would be obtained in the Jewish quarter, along with the flour that was designated on the bread ration card. Nearby, various groups were also dragged along. The agents of the criminal police knew about the smuggling and were well paid for this and, consequently, made sure that the business would not be harmed. Understand that these costs made the price for bread and cereals more expensive.

Potatoes, which were a very important food, were provided by the Judenrat, which would receive the potatoes from the Polish rolnik [farmer] according to the instructions of the regime, but here, too, they had to give gifts.

The butchers would smuggle in meat. However, smuggling was very risky and they did not have the help of the agents of the criminal police, but the opposite, the agents would beat them fearlessly. Very often, the butchers would cut [the meat] very badly. However, it is clear that meat was very expensive and only a small part of the population could permit themselves the luxury.

The Jewish intelligentsia, besides doctors, lived in very difficult conditions because they lost their economic base. The change in status that befell them was not easy, in particular because the adjustment took place under German blows. They sold everything in their houses that they had acquired over the course of years of work. Particularly difficult was the situation for the members of the intelligentsia who were refugees for whom their surrounding was completely unfamiliar. They did not even have any contact with those who had influence at the labor office who would have made it possible for them to receive the appropriate workplaces.

The Filipówer Rabbi, who had been brought with the Sulwalker Jews, was living in Biala. After the death of Rabbi Moshe Utszen (died of typhus in the winter of 1940/1) all of those who had need of a rabbi turned to this rabbi. The Filipówer Rabbi had the reputation of a scholar and also was well versed in worldly knowledge. Taking into consideration that there was no house of prayer in the entire quarter, not one kloyz [small synagogue], not any religious institution, it was understandable that the rabbi's influence on the life of the quarter was minimal.

During the Days of Awe, there were places where large minyonim [prayer groups of at least 10 men] prayed. There were also small minyonim in private apartments that prayed three times a day the entire year.

There was no cultural activity in the Jewish quarter. Everyone was busy with themselves and with coping with their daily hardships.

The large Tarbus [secular Zionist] library was moved from Wolnoszczi Square to the premises of the kehile at Brisker Street. Yakov Ahron Rozenbaum, the chairman of the Zionist organization, carefully protected the treasure. At first, the Bundist library was moved to the apartment of Elihu Hofman (Bubkes [nickname meaning nonsense]). He took great care of the books, but because of the constantly growing crowdedness in his apartment, he had to take the books out to the stall. Only Mrs. Liuba Tuchsznajder's Froebel school [kindergarten] at Grabanower Street existed in the quarter. The school ostensibly had the permission of the Polish school supervisor.

Many young people studied with perseverance at home and prepared to take exams as soon as the German chains were thrown off.

Although it was forbidden for Jews to buy newspapers, they would receive Polish and German newspapers in the quarter. The radio news, which the Germans would broadcast through a megaphone at the market orchard, would be gathered by children and delivered by them in the quarter.

Illegal publications came into Jewish hands very often, but it was difficult to see an organized hand in this. A Jew simply received a page from a Christian acquaintance and would bring it to [other] Jews.

News Gatherers

The short, frosty winter days would pass. At night, we sat imprisoned in the houses and

[Page 414]

considered Hitler's defeat. The Germans installed a radio location in the Biala city garden that would give political news several times a day. One was drawn to the radio loudspeakers, but Jews were afraid to risk it because if they were caught listening to the radio their lives were insecure.

As the passion to hear the news of Hitler's defeat was great, they had an ingenious idea: they would send small children to the loudspeaker to grab the ether-waves and they would delight the Jews with a little news.

Children stood outside in the frost; their small noses and eyes dripped, but the childish minds strained to take in even more news. When the radio broadcast ended and the children returned to the Jewish quarter, the adults were waiting and overwhelmed them with a flood of questions. However, the children did not want to answer because each of them had a circle of news-takers and they did not want to tell [the news] to strangers.

We will describe one such group here. Among other news gatherers was a small boy, Nota Osnholc, who specialized in catching the radio news near the radio loudspeakers in the market orchard. [He was] a child of about 11 or 12. Before the war he went to a Polish public school and to a kheder [religious primary school]. He was an emaciated child, really skin and bones, with a pair of glowing eyes and a sharp, very sharp, little mind.

Several times every day, this child would leave the Jewish quarter discretely for the radio megaphone. Badly dressed, there he would jump from one foot to the other in the cold and take in every reverberation from the wide world.

So this young boy would give an overview of all of the news he had heard that day on the radio to his group every evening and take part in the political conversations. They would sit and gape, hearing the child relating the war communications. [He] never ate his full; his small voice vibrated weakly, but he enumerated all of the places of the battlefields clear and exact, even from the Far East, with the ringing names so strange to our ears. The child's mastery of politics was astonishing.

In the circle for which the child Nota was the news bringer, people who had no idea about politics would come at night. However, they marveled at the young boy who breathed hard, had no strength to speak and yet how he “operated” the fighting ships, all kinds of airplanes and other heavy weapons.

When they would call for Nota from his home, it took a long time until the child could tear himself away from the political debates. And Nota's mother would complain: So, Nota, what will be? I do not know how we will get wood or something else for the house and you are busy with politics? And when the child would leave, people would often call to him: so, in fact, is there such a child among the Christians! Who has such a child who can be so clear about all of today's political problems as this child?

The circle to which the child, Nota, would provide the radio news, also had two other news gatherers and very talented politicians.

[One of them was] Chaim Zilberberg, the youngest son of the dentist, Yoal Zilberberg, a young man of 20. Sickly from birth and a constant client of doctors. He graduated from gymnazie [secondary school], where he was one of the best students, just before the war. Chaim Zilberberg was freed from forced labor as someone who was sick. He would diligently study the German press the entire day and would find what was unsaid between the lines, from which he would construct his political theses. His room was filled with maps, on which he would follow the war operations. His mother would often make scenes about the maps, afraid that during a search there could be a bad outcome with such material; how does a Jew come to have maps?

The other one was Moshe Lichtenbaum, Leibl Mednik's grandson, a young man of 18. He studied in kheder [religious primary school] and studied worldly subjects privately. Before the war, he was harnessed in the business of his parents. He was also dedicated to politics with his entire being and was clear about every battlefield. His work was dependent on the German press, which he received through various ruses and shared with the young Zilberberg.

Moshe also was freed from forced labor because he had a problem with a foot from childhood on. However, he gave up his privilege and settled into his work as a carpenter in the workshop of the volks-Deutsch Kraskowski. Entering a workshop had cost him several hundred zlotes and he did this with a purpose. There was a radio in the house of the volks-Deutsch and Moshe was a strong enthusiast for hearing a little radio from abroad; as a result, it was the right decision for him to go for the instruction as a carpenter. He became friendly with the volks-Deutsch, who was an old communist and [Moshe] very often spent time with him in his house. There he would

[Page 415]

manipulate the radio and receive a great amount of news from London.

This young man also remained in contact with comrades who worked for prominent men as house workers and in whom the brown [shirt] tyrants had trust, leaving them the keys to their residences when spending time in Germany on furlough. Moshe was the first to make use of these places to listen to the radio from abroad. He would spend entire nights there and what could be a better place for hearing the radio from abroad than in a Nazi's house? Moshe was really “stuffed” with news from abroad. When Jews would take him into a small group, he spoke for a long time before they let him leave.

Moshe did not want to leave the radio news to the young boy Nuta. Mainly, he did not have the patience to wait until Nuta would give the report. He himself ran to the radio loudspeaker in the municipal garden. He was successful at the beginning, but later he had his bones severely broken for wanting to listen to the radio. When it was very difficult for a Jew to approach the radio loudspeaker, Moshe could be found standing at the gate of Yisroel Shualke's courtyard and one would see how he strained his ears to catch something from the loudspeaker. In the middle of the busiest work in the workshop, he would disappear when it came time for the news from the radio.

The First Expulsion

Shabbos, the 6th of June 1942 (21st of Sivan 5702) a rumor spread in the city that all Biala Jews had to leave the city. We later learned that the county district had informed the Judenrat that on Wednesday, the 10th of June, all of the Jews who were not employed by the labor office had to appear at the train to leave. The order concerned all of the Jews in the county. All of the provincial cities would become free of Jews and all of the working Jews from the entire county would be located in Biala.

Yakov Ahron Rozenbaum, the representative of the Judenrat, dared to ask the consultant, Lipowski: Where are you sending the people? The official answered: To the west. The representative of the Judenrat again remarked that he knew that the Jews from the west were being sent to the east, so why had the Biala Jews become so displeasing that they were being sent to the west? The official remained embarrassed for a while, but he regained his composure and said: “You see in what conditions the people are living in the synagogue and in the remaining prayer houses.” To this

|

|

From the right: Wowtshe Rozenbaum (Lodz), Asher Fajenbaum, Moshe Fajenbaum, Shimshon Justman, Yosef Ejdlman, Shlomo Cyker, Itshe Kanier (Serock), Yakov Brodacz, Chaim Zavl Milbaum, Zilie (Euzial) Fajenbaum, Berl Sznajderman, Moshe Lichtenbaum, Benedict Kraskowski; From the front, sitting: Frei (Grodna), Yehosha Fajenbaum; From the back, standing: Szulman (eastern section), Zile (Euzial) Gutenberg |

Y. A. Rozenbaum responded: “Yes, true, we would not be against bettering the situation of the people, but we know that, in general, this is not in the interest of the government, so why does it bother you that the people will die here?”

The official had no right to a place in the discussion. Not having more to say, he answered: “You, Rozenbaum, see everything in black; therefore, with that attitude any collaboration with you will not be possible.”

The Judenrat began an energetic action to repeal the edict and boarded up all thresholds [houses]. At the Gestapo, they asked why they had not been entrusted with such “a piece of work.”

The Judenrat succeeded in learning that the edict had come from Lublin, but it did not provide any number of how many should be deported. The administrative district was interested that in the deportation numbers should be more specific.

After all efforts by the Judenrat, it became clear who could remain and who must leave. All of those who had work cards as well as merchants and artisans who were employed by the administrative district had the right to remain, along with their wives and children up to the age of 14. These

[Page 416]

women and children needed to receive separately stamped receipts from the labor office and from the captain to legitimize themselves for the regime. Every emigrant had the right to take up to 10 kilograms of hand luggage. For not conforming to this order there was the threat of death.

The regime, for its part, informed the Judenrat that the entire action had to be led by the Judenrat and the Jewish ordnungsdienst [ghetto police]. If they could not control the situation, the regime would be forced to engage with it and that could lead to unwanted consequences.

On Tuesday, the Judenrat, through notices in the street, informed the Jewish population of everything and designated an assembly point at the synagogue courtyard.

On Shabbos, as soon as it was clear that one could escape from the expulsion with a work card, a large part of the population began to make an effort to obtain such a card. Many succeeded by making high payments to receive a card for living.

Young men, who had gone around with young women for years and did not intend to get married during the time of war, quickly got married in order to save their brides [girlfriends] from expulsion and thus legalized their brides as their wives. Fictitious marriages also took place in order to save Jewish women.

There were those who could not legally save themselves; they decided on the spot not to appear and to hide during the time of the aktsia [deportation]. Many ran away illegally in time to the closest villages to Christian acquaintances and to neighboring Mezritch. Those who decided to leave began to prepare for the road and to prepare packs.

In the provincial shtetlekh [towns] of the county, the Jews ran to the forests. In general, they did not have in mind to appear for the migration.

Tuesday afternoon, the taxation office in Biala also showed what it was capable of doing. Almost all of the officials, accompanied by policemen, started going through the Jewish quarter demanding of the Jews the required and also even more unevaluated taxes for 1942. They demanded extremely high sums that had to be paid immediately because if not they threatened arrest and appearing the next day for the deportation transports.

The same day, Yakov Malina went to the administrative district to take care of some matter. At night, we learned that Malina was taken away outside the city in an auto and shot by agent Baldiga.

Tragic moments took place in families; parents could not cope with their children and children not with their parents. No one had the strength to say to the other – remain. Because death called out from every order.

On Wednesday, the 10th of June, 700 souls in their holiday clothes with packs of various sizes assembled at the synagogue courtyard. People streamed there from all directions. The Jewish ordnungsdienst, which had been enlarged to 50 people specially for this purpose, went from house to house and reminded people about the obligation to appear at the synagogue courtyard. Those who belonged to the lucky ones and remained in the city moved freely in the Jewish quarter, where no controls were enforced.

The representatives of the regime arrived at the synagogue courtyard and watched the scene. They sent home some of the crippled, sick and nursing women. They ordered that the sick, those not capable of being transported should remain at home. Understand that this strengthened even more the impression that the people were only being evacuated to another city. Many who had decided not to appear, now took their packs and came to the synagogue courtyard.

At around two o'clock in the afternoon when the synagogue courtyard was full of Jews, the group along with Jewish ordnungsdienst, accompanied by several gendarmes, was led to the train where it was turned over to the sonderdienst [special services] of the administrative district. A number of weak Jews were brought to the train by auto.

It is difficult to list all of the Bialers who marched in the procession to the train. Several faces have remained etched in my memory: Moshe Kawa, known and beloved by everyone, went, resigned and prematurely old. Near him walked the good-natured teacher, Yoal Meir Hajblom. Among the lines could be noticed the merchant Yosef Gilman and his family, Pintshe Eidlman and his wife and small son, Hercl Czarni and his wife.

The Jews had to wait at the train station until morning because it seems the deportation had been carried out early and no wagons had been prepared for the people. The Judenrat brought bread and coffee to the train several times.

Early Thursday, a freight train arrived and by around 11 o'clock in the morning, the people already were in the closed wagons. The train moved from the spot in the

[Page 417]

company of a Stormist and several Ukrainians guards, in the direction of Łuków.

The Judenrat, at any cost, wanted to learn to where the people had been sent. They learned from the Łuków Judenrat that the train left in the direction of Lublin; from the Lublin Judenrat – in Majdan Tatarski – came the news that the people had gone in the direction of Chelm. And Chelm reported that the train had passed through the city on Friday evening in the direction of Wlodawa. The last news came from Wlodawa, from which they reported that they knew nothing and that they should not be asked such questions again.

At Wlodawa, the thread was torn. And because such an answer was given from there, it was surmised that in Wlodawa they did know what had happened to the people.

The administrative district also learned about the constant rumors that there was news from the people who had been sent away. It, therefore, tried to tap the pulse of the Judenrat, but the Judenrat answered: “We called the people to report for emigration and where you sent them, you know and not us.”

Actually, the Judenrat learned where the people were being sent. It came to light that the last train station of their wandering was Sobibor, 37 kilometers from Chelm, in the direction of Wlodawa. Before the war, Sobibor was well-known as a small train station between forests in the Wlodawa area, from which wood would be transported.

Later, we heard that many Jews had been brought to Sobibor and they were left sealed for several days in freight cars without food and without a drop of water on a hot summer day on a side train line in a forest. Afterwards, the bodies were thrown out of the train cars and burned there.

Weeks passed and the thinking about the uprooted victims did not cease. It was natural that the German regime became the inheritor of the few possessions that the victims had left in their apartments. The apartments that had been left were thoroughly cleaned.

The month of July passed relatively calmly and the month of August arrived, which was so rich in bloody events.

On Monday, the 3rd of August, in the afternoon, Ahron Brodacz was arrested at the district administration. At the same time, the sonderdienst began to search for Menakhem Finkelsztajn. Not being able to find him, it arrested the Judenrat chairman, Yitzhak Piczic, as a hostage, threatening to shoot him if Finkelsztajn did not appear. After a short time, Menakhem Finkelsztajn appeared at the district administration and Yitzhak Piczic was freed. The news about the arrest of the two Jews made a strong impression in the city because they knew that both had been visitors at the district administration and had “support” in the person of the officials Engineer Debus and Naulinger. Relatives and friends warned them of the consequence of maintaining contact with the Nazis, with whom they would from time to time have success in obtaining a favor for a Jew for a good reward.

Right after the arrest of Ahron Brodacz, a search was carried out in his residence by the sonderdienst. Consequently, his sister and his wife, Chaya Fajbenbaum, and her two sisters were held.

For an entire afternoon, the families of the arrestees made every possible effort to learn something, but without success. No one knew what to say, but everyone was calmed, believing that this was a misunderstanding that would quickly be clarified. Thus the day passed without any success until the curfew arrived for Jews, seven o'clock at night, and the families of the arrestees had to return home with mixed feelings of fear and hope.

The end was a tragic one. That same night, all of those held, the women and the men were shot. They said in the city that this was the German officials wanting to erase the traces of their contact with these Jews and that the official, Naulinger of Passau (Germany), had a hand in the murders.

In the middle of the night, on Monday into Tuesday of the 4th of August, we suddenly heard heavy military steps in the streets of the Jewish quarter. As soon as the sun began to come up, we heard the wild Gebril: Mener raus [men, out]! The entire Jewish quarter was surrounded by gendarmes, security police, Polish police, Gestapo and Goering's troops – the pilots, all armed with machine guns and grenades. Grabanower Street was full of men, who were chased to the corner of the street (in the direction of the new market). Those who were late were accompanied on their way with blows from rifle butts. After a time, the Germans began to check the work cards. The checking lasted several hours and all the men were freed.

However, these almost “innocent” checks that

[Page 418]

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Plan of the Biala Jewish quarter during the Nazi regime |

morning cost the Jewish population 19 victims. Among them were: Zalman Liverant, Yukl Listgartn, Fridman (from eastern Kresy [“Eastern Borderlands” of Poland], a former war prisoner) and so on. Many of those who returned alive had been severely beaten and bloodied during the check.

Faisker,[b] the Gestapo man, led this aktsia and the volks-Deutsch, gendarme Leon Busch, excelled particularly bloodily.

On the part of the accused, witnesses such as the shoemaker, W. Ivanicki, former Biala vice-mayor appeared. After he gave his testimony, Faisker stood up and gave the following statement: “I expected that Jews would appear here against me. I can also understand the appearances of Poles as witnesses against me. But how does Ivanicki come here? This Ivanicki, who was a Gestapo confidant who denounced tens of Poles to the Gestapo and brought about their death – how dare he appear in court against me?”

Ivanicki was arrested on the spot. The court sentenced him to 10 years in prison, to losing his rights as a citizen for 15 years and the confiscation of his possession on behalf of the state treasury (provided by Yehosha Wajsman – Israel.)

The events in the city began to unwind with particular speed.

On Friday, the 7th of August, the Judenrat announced that according to the order of the regime, all Jews had until six o'clock in the evening to move to the smaller quarter, according to how it had earlier been planned.

The Jewish quarter that was located between the streets, Grabanower and the synagogue courtyard alleys (except for several houses bordering on the new market), Janower (only on the right side), Prosta (from the court on) and Cmentarne, would now be enclosed like a four-corned box between the streets (without the synagogue alleys – from Wolnoszczi Square to Prosta), Prosta, only on the left side (from Grabanower to Przechodnia), Janower, the right side until Przechodnia and Przechodnia only the right side.

There really was the threat of suffocating in such a narrow cage. Although the quarter was not closed, people already lived in stalls, so that it was an instrument of torture deciding where to go.

The Judenrat still tried to intervene with the S.D. representative Glet, who had promised to try to have the order revoked and it was actually soon withdrawn.

In a conversation between the S.D. [Sicherheitsdienst – Security Service] man and the Judenrat representative, Y. A. Rozenbaum, the former blurted out that the order would certainly be revoked because other mass means were being planned against the Jews. However, what kind of mass means these were, they could not learn from him, but time lifted the veil of this mystery.

On Monday, the 10th of August, a rumor spread in the city that freight cars were standing at the train station in which 400 men would be taken from Biala to Lublin. This information was confirmed because all of the German offices were telephoned from the train station and they were asked about the Jews who were supposed to leave. Everywhere they answered that they did not know anything.

Wednesday, in the morning of the 12th of August, a search was carried out for the Jewish men by an unfamiliar security policeman with the help of the Ukrainian militia. The detained Jews were taken to an assembly place on the Wolya. Among those held were many workers from the Wahrmacht [German armed forces] and from the German workplaces, which made efforts

[Page 419]

to free them. The S.D. representative, Wida, announced the search to the Judenrat who left for the assembly point at the Wolya and freed all of the Jews.

|

|

| Restriction on movement for Biala Jews |

It did not take long and there again was panic in the city because the search for men was resumed. An order came simultaneously from the district administration that the Judenrat, the aid committee and [those in] the disinfection colony should appear immediately at the square of the district administration.

To those assembled at the square of the district administration, the official, Lipkow, asked the assembled women of the aid committee and of the disinfection colony to go home and he disappeared. A vehicle with unfamiliar security police and a few Ukrainians arrived at the square. The Jews were loaded into the vehicle and they were taken to the train.

Despair reigned in the city because it was clear that with the removal of the Judenrat, the city had been abandoned and the end of the tragedy was approaching. We were sure that a search would soon be made for men because many were still missing from the number that had been caught during the morning search. It really did not take long before a new search began.

The catching of 400 Jews was not easy because the majority of the Jewish workers were already at the workplaces. Therefore, the search persisted an entire day. And when the nightmarish day turned to night, a dead Jew with a smashed head lay in the gutter at Narutowicz Street and in a small room lay a woman who had been shot, Mrs. Brukha Adlersztajn (Moshe'e the saloonkeeper's daughter-in-law), who would not let herself be raped by a Ukrainian who took part in the deportation.