|

|

|

[Page 47]

by M. Y. Fiegenboim

Translated by Ofra Anson

On the first day of the German–Polish war, September 1, 1939, Biala experienced fire and blood. Vollia was bombed early Friday morning, in an effort to destroy the airplane factory. Bombs fell on civilian houses, including a Jewish house where all members of the carpenter, Abraham Itlbaum's family, lost their lives.

It was clear that Poland was not prepared for the war. The airplane factory had not been protected, and no Polish airplanes tried to intercept the German attack. Yet, there was hope that, after that day, which took Poland by surprise, things would change.

There were no signs of any of the government promises, “we are united, strong, and prepared”. Chaos and embarrassment increased all the time. German bombers flew freely in Biala's skies, wreaking havoc and destruction. People lay on the ground in the fields all day long, and started to move at night, after the German bombers had stopped their work. The first thing they did was to bury the day's victims.

The airplane factory was already in ruins, almost all the Polish army had left Biala, but the Germans kept bombing. Among the destroyed houses were: the beautiful house of Heartglass, the elementary school in Grabanover Street (the house of Motl Mowiness), Shimom Lichtenstein's house on Brisker Street, Papinski's house on Janaver Street, and others.

German tanks entered the town, shooting, on New Year Eve, turned to Brisker Street, and drove to the Brisk Road. A Polish officer, with his small company, opened fire on the tanks by the new market. As a result, most of the huts in the new market caught fire.

Within two weeks, it was clear that Poland had lost the war. Naturally, the future under the German occupation frightened the Jewish population. They found some hope in the information that the Russian army was marching west and that, according the German–Russian agreement, the border would be at the Wisla, which meant that Biala will be in Russian hands.

Indeed, the Russian army occupied Biala on September 26, 1939, and kept moving west.

Succoth was celebrated heavy heartedly. They were pleased they did not fall into German hands, but feared the future.

The Russians did not bother to make order in town. They left it to the local population. Several committees were established, all by Christians. Remembering their bitter experience of 1920, Jews avoided cooperation with the new regime.

Shops were often closed, and soon there was a shortage of basic ingredients. People started exchanging goods; in front of each open store was a long line, and people bought anything they saw.

Succoth was not a happy holiday. At the end of September, the radio reported that the border would not be by the Wisla River but by the river Bug. The information soon spread among the Jews, and the fear was enormous.

Although the Russian soldiers denied the truth of this information, there were signs that they were going to withdraw to the east. They started to load valuables on trucks. Even from the Jewish hospital, expensive medical instruments were confiscated.

Some thought to leave the town and move to the other side of the Bug River. It was a real possibility, because the Russians did not restricted population movements to the east. Yet, as mentioned, the Jews of Biala had had bad experiences in WWI and in 1920. Then, those who stayed in the town had a fearful time, while the refugees really suffered. Nobody, of course, could imagine the horrible end. They suspected that the times would be difficult; but when had Jewish life in Poland not been difficult?

They knew that life under the Russian regime would not be easy, and everybody lived in hope that Germany would quickly lose the war, and that a free, open, world would lie ahead. On the other hand, moving to Russia would put the refugees in a camp that was vulnerable to a variety of difficulties and hazards.

The greatest fear was that it would be impossible to leave Russia after the war. Those who decided to leave town had one answer to all questions:

[Page 48]

”We do not want to live with the Germans, and even less with Hitler's Germans!” About 500–600 Jews probably left town, most of them men who left their families behind, assuming that the Germans will be after men rather than the women and children.

Those who left for Russia came from all social strata. Most of them never had any connections to Communism. Those who were known to support the Communist regime, stayed in Biala.

One cannot blame Biala's Jews for staying in their hometown. If the leaders of the Jewish Federation did not know about Hitler's extermination program, how could the Jews in this small town know about it?

The End of 1939

On October 10, 1939, the Russian army left, and the German army entered town. The Jews were so frightened, that many, who had not decided to leave town before, left now.

A few hours after the Germans entered the town, they started taking Jews as hostages (the head of the town's administration provided the list). Christians wearing white bands were seen on the streets, and their first duty was to capture Jews for forced labor. The Germans were never short of work, and the Poles were happy to provide them with Jewish labor, even with more than they asked for.

The German regime ordered everyone to open the shops, and tried to get the town functioning. For few days, they did, indeed, succeed. There was a curfew the whole time the Germans ruled the town and for Jews the curfew lasted longer hours than it did for Christians.

The local government was, for the moment, in the hands of the army. It seems that at this point they did not have any orders concerning the Jews. Indeed, Jews received traveling permission to go to Warsaw and Lodz to bring merchandise. Trade started to flourish, and, free from the heavy Polish taxes, the Jews felt some relief, forgetting the threatening reality. Yet, the relief lasted a short time. In November 1939 the Gestapo arrived and started the Via Dolorosa which led to the total destruction of the Jews.

The Gestapo settled in the palace of the factory of Raabe in Vollia. Its first contact with the Jews was a demand for a contribution of several ten thousand Zlotys. In order to expedite the contribution, they arrested a number of Jews and tortured them. They were released when the full sum had been paid.

The Gestapo on the street aroused panic among the Jews, who abandoned the streets. Abraham Lubeltzik, the printing house owner, died from a heart attack when he heard that the Gestapo were on their way to him.

In Beith Hamidrash the Gestapo found the janitor, Joel Greenglass, standing alone in his Talith and Tephilin. They forced him to climb on a ladder they had brought, and made other Jews carry the ladder on their shoulders in the streets around the town.

When the Gestapo entered town, an additional several dozen Jews left the town. Leaving town was more difficult now, as the borders were guarded. Among those who ran away was Biala's Rabbi, Tzvi Hirshhorn.

Any Jew that accidentally met the brown murderers was brutally beaten. They robbed Jewish stores, and took money out of drawers. The economic life of the Jews stopped. The Germans started to eliminate Jewish businesses. The big Jewish stores were confiscated, their merchandise taken on trucks, their owners put in jail until a large ransom had been paid. Workshops and working tools of Jewish artisans were confiscated.

|

|

[Page 49]

In an effort to save their property, some Jewish merchants gave their businesses to Christian acquaintances, ensuring their ownership in legal contracts. Only a minority of these Christians kept the contract, most of them did all they could to get rid of the Jewish owners. There was nothing the Jews, who were already helpless and without civil rights, could have done.

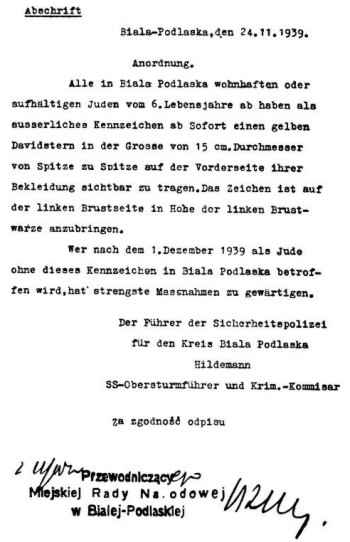

In November 1939, the Gestapo's commissar, Hildeman[a], ordered that each Jew above the age of 6 has to wear a 15cm yellow Magen David patch on the left side of his/her chest. This was later replaced by a white band, with a blue Magen David, on the right arm. Leaving town with no permission from the Germans was forbidden.

One day, the members of the last community committee were called to the Gestapo. They were ordered to organize a “Jewish Council” immediately. The council, which included more members than the original committee, was based in the community hall on Brisk Street.

The Germans now had an agent to which they could turn with their demands. There was a constant stream of demands to the “Jewish Council”, which took a lot of resources from the Jewish population. Beside money, they also had to supply hundreds of workers. The workers were never paid for their work, and were often beaten during work. The “Jewish Council” had to organize the workers and to pay them for their work, knowing that otherwise they would have no source of income to support themselves and their families.

The occupation activated all the local governing institutions, and the Polish administration largely cooperated. The latter took revenge on the Jews for Poland's defeat. They took every opportunity to make the Jews be aware of them.

The tax office resumed work, and started to collect the debts of the Jews. The clerks Gerach and Kunitzki were particularly active collectors. A Jew that did not pay his debts immediately was arrested and tortured.

The head of the apartments office, Bieletzki, used to walk around the streets and confiscate Jewish apartments for Christians, who suddenly found out that their current apartments were too small for their needs. They happily helped the Germans to load the Jews' furniture onto trucks; Tchibulski, the jail keeper, was particularly enthusiastic.

Germans and Poles alike asked delegates from the “Jewish Council” for presents every time came to the town's office on some errand. The worst were the head–of–civilians, Antony Wallawski, his deputy Stephen Shzapan and the head of the apartments' office, Bieletzki.

In addition, these people encouraged the movement of Jews into the ghetto, the smallest and the narrowest possible.

At the end of 1939, Jews from Suwalki and Serock were brought to Biala. These Jews were taken from the market places in their home towns and were taken to other cities in the Lublin Region. They were not allowed to take anything before they were pushed into trains. The refugees told the locals about the inhuman tortures they had already suffered during the few months of German occupation.

About 2,000 refugees came to Biala. The local Jews took in most of them to their own apartments, the rest settled in Beith Hmidrash and the Hassidic prayer houses. Some refugees went to Warsaw and other cities.

1940

At the beginning of 1940, Jewish war prisoners from the former Polish army were brought to Biala from Lublin. They originally came from the far east of Poland.

The road they were taken through was full of their blood and the graves of their fellow Jewish soldiers. They were brought from Germany to Lublin, and from Lublin to Biala they walked by foot. On their way, the Germans shot many of them with their automatic guns. They were locked in Pizitz camp on Brisk Road.

The Germans built Pizitz camp, using the Jewish workers supplied daily by the “Jewish Council”. When they started building it, the head–of–civilians, Wallawski, told the Jewish workers that the camp will host Jews, who will arrive at the beginning of April. The workers felt desperate.

The jail was full of Jews who suffered real abuse. Jews were in jail for not paying the contribution or tax; others because they supposedly hid their merchandise; artisans for supposedly hiding the things they had made. For hiding merchandise, the merchants Josef Gitlman, Fishl Wulos, and Moshe Itzhak Biderman sat in Lublin jail.

Jews started to work a little, and got 2 Zlotys for a day's work. This was not enough for living.

Some turned to illegal trade, and were able to make a living. Although Jews were forbidden to travel by train, some risked their lives and went to Warsaw, dressed as Christians, to bring in some goods.

During the day, until sunset, some shops were open.

[Page 50]

Most people could not get anything there, as trade was very limited. A trusted client, however, could get almost everything.

New decrees were constantly imposed on the Jews. Their last economic positions were destroyed by the Germans. Even their small stores were closed and their goods confiscated. Only a handful of shops remained on Grabanover Street, and the Germans often changed the owners. Even the smallest store was marked by a large Magen David, which had to be bought from the local regime for a large sum of money.

Two large placards, hung at the entrance to Grabanover Street from the market side, declared: “Epidemic – danger! Arians are not allowed in”. Jews were not allowed in the Market Square, which made access to the post office difficult. Jews tried to avoid the post in any case, because standing in line exposed them to all sorts of hassles. The “Jewish Council” managed to establish a branch of the post office, which also had a telephone. Every day two members of the council went to the German post office and dealt with the needs of the Jewish population.

On the eve of the high holidays, the Jews of Vollia were ordered to move to town, and Vollia became free of Jews.

The use of balconies was forbidden. If the balcony was made of metal, it had to be dismantled. Jews had to give the Germans all the metal they had, while the Poles had to hand in only 3Kg.

The refugees that settled in the synagogue and Beith Hamidrash lived in terrible conditions. The cold winter afflicted them bitterly. All the wood from the Jewish quarter had been used, trying to keep warm. The wood from the floor and the windows of the synagogue and Beith Hamidrash, the wooden fences, and even the trees from the cemetery.

They were pleased when the short winter day passed and the long night came. People locked themselves in, told each other the news, and waited for Germany's defeat.

Although the German–Russian border was well guarded, some succeeded in crossing into Russia. They reported home that many of those who left for Russia desperately want to return to Biala. They were tired of being refugees, and they thought that on the German side of the border the Jews' economic situation was not too bad.

In May 1940, a train from Russia carried refugees who returned to Poland. Among them were many Jews from Biala. They were amazed how well the Germans treated them.

During the war in West Europe, the Germans repeatedly told the Jews that Germany was winning.

One morning, the Gestapo called the “Jewish Council” in. The stood in line while Gestapo Kot read to them a report from a German newspaper, saying that Weitzman–troop has been recruited in Israel to fight Germany. For that purpose, a Jewish state, headed by the King of England had been established. When he had done reading, Gestapo soldiers came into the room to beat the members of the “Jewish Council” with their sticks.

In March 1940, all the Jews were ordered to register for forced labor. Many got a note from a doctor that they are not able to work, and brought the notes to the “Jewish Council”.

The sad, forced labor episode started in June 1940. Jews from Miedzyrzec, and later from other cities, were brought to Biala. Pizitz camp filled with Jews, who worked in construction. Most of Biala's Jews managed to arrange easier work that was still considered as forced labor and at the end of the day they returned to their homes. Only a few of them worked in construction, mainly in the town itself.

The German engineer Greenfield managed the construction. The supervisors were SS police and their helpers, ethnic–Germans (I am not sure what the writer means. He may refer to fact that the SS first recruited the unemployed and bandits, O.A.).

Jews were looking for ways to avoid forced labor. It was not too difficult, because every German had already found a Jew who dealt with freeing Jews, and the slave trade of Jews began. Naturally, not everybody could afford to pay the large ransom. Indeed, the poor stayed in the camps until the middle of the autumn.

While on one hand the SS freed Jews from the camps and the work for a handsome payment, on the other, trying to disguise these illegal actions, worsened the conditions of work and in the camps. One day, the SS Shwach came to the worksite, and, with no reason, shot Jewish workers from Miedzyrzec.

One early morning in July 1940, there was a surprise search for Jewish men. They were taken to the camp on Artillery Street. One might have thought that all Jewish men would be taken from town. The women had a hard time; they could not even go out of their homes, because the curfew was still in effect.

When all men were gathered by the big ditch next to the 9th battalion, the Germans inspected their work cards. Most of the men were sent back home, others were taken by train to an unknown place.

Similar searches took place in other cities in the Lublin region the same night. They soon learnt that the men on the train were taken to forced labor in Belzec.

The “Jewish Council” worked hard to free Biala's men from Belzec. Yet it took time.

[Page 51]

Young Mordechai (Motl) Hofer was one of the victims in Belzec.

The “Jewish Council” established the employment office in the autumn of 1940. The Jews who worked there were: Emil Weinberg, Adek Slobovski (from Warsaw), Tuchshneider, Dova Kreiselman Levi (son of Yitzhak Levi), Chamilevski, Tzimeman (Sulwalki), and a young woman from Serock. Although the “Jewish Council” hired and paid the workers in the employment office, it had very little influence on them. Slobovski, for example, used his position to for blackmailing his Jewish customers.

The employment office served only Jews, but the German, Lehman, a former worker of the airplane factory, managed it. The Jews used to say that he is not a bad 'Goy'. He used to take money from Jews, but did not inform to the Gestapo or to the “Special Nazi Court” for misbehavior, and punished them himself. Sometimes he beat Jews bitterly, but they were thankful he did not hand them over to the Gestapo. Sometimes Lehman beat Jews for no reason, but the Jews said the he was nervous and needed to show that the employment office had a real Nazi orientation.

There was a case of young Jewish men who were taken to the Gestapo for not coming to work on time. The “Special Nazi Court” sent them to jail for years. Young Sigelman from Garnzcarska Street was one of them.

After a while, the employment office did not have to make an effort to recruit Jews for work. On the contrary, Jews were begging for work, they needed the few Zlotys they could earn. They also did not want to be identified by the Germans as unemployed; the work was hard, but it was more convenient than staying in the camps. At least they could come home after a day of hard labor and being beaten.

Those days, Jews were still paid 3–4 Zlotys a day. In the carpentry factory, a worker could get up to 10 Zlotys a day. The Christians who worked there could not make that kind of money. On top of this, Jews returned home with bags full of wood they could sell. By comparison, the price of bread was still quite reasonable, 0.75–1.00 Zloty for one kilogram.

Jews were employed mainly by the army or by German firms. Among them were: “Benz”, “Mayer”, “Seeger–Werner”, “Stuag”, and “Zid”.

”Mayer”, “Seeger–Werner” operated in the airport. Pay was low, beating was frequent. “Benz” was the worst from this respect. Lehman, the manager of the employment office, used to send those who deserved punishment to “Benz”.

”Zid” employed Jews to build sheds for the Sicherheitspolizei (SIPO) on Jonava Road. Here, too, Jews worked for low pay and high suffering.

”Stuag” fixed roads. Work was hard and dangerous. They worked with boiled tar that gave off a gas that burnt their face. They did not have any safety equipment and workers were often brought to the hospital in a serious condition.

Jews also worked in large firms owned by Polish and Ethnic–Germans such as Zawudski's sawmill and the carpentry originally owned by Herzl Tcharni in Raabe's factory and in Housheid's carpentry, located in Pizitz's sawmill.

Jews tried to build factories and hand them over to German civilians that came to Biala to confiscate Jewish property. Thus, a brush factory was built on Garnczaska Street, managed by the expert Munia Suchartzik from Miedzyrzec. At the beginning, the “Jewish Council” managed the factory, but it was soon taken over by the German Wanzura, the brother in law of Fritz, the deputy Head of the region.

Wanzura also got the soap factory of Sara Gele Goldfarb in Vollia, and made it into a big factory. The professional managers were the Jewish refugees Bibrovski and Wolf Weitzman. He did not settle for these two, and took the Jewish printing houses of Lubeltzik and Hochman, and made one big printing house on Pilsudski Street.

Biala's Jews had “equal rights” in the working sphere, and even got governmental positions. They worked also in the regional administration and other German positions as couriers, drivers, and mechanics as well as working for the army. For the army, Jewish work was crucial.

Although the employment office supplied all the demand for working men, the kidnaping of Jews continued. There were Germans who simply enjoyed walking the streets and chasing Jews. The kidnapers did not need Jewish work, they just wanted to abuse them.

1941

At the beginning of 1941, the German made an expulsion attempt. One winter morning, the gendarme and the police went out on the streets, kidnaped several Jewish women and elderly persons, and took them to Opole, near Rossosz. A few days later all of them returned to town. It was difficult to understand what the Germans were trying to do.

The war epidemic, typhoid, started to spread in the Jewish quarter. Houses were crowded, and sanitary conditions were poor. The yards were also filthy, because it was not suitable for so many residents. The sanitary department of the “Jewish Council” could not keep up with the needs.

[Page 52]

The “Jewish Council” was responsible for the Jewish hospital, which was always crowded. At the beginning of the German occupation, there were no Jewish physicians in town, and the Christian doctors were not allowed to treat Jewish patients. In the summer of 1940, three Jewish doctors came: Dr. Bergman (from Kattowitz), Dr. Hochman (a German refugee who arrived via Warsaw), and Dr. Rubinstein (from Warsaw). The surgeon Dr. Gelfish came in 1941. There were two medics: Haiim Musawutz (Kobriner) and Berish Weisman (from Lomazy).

Attached to the “Jewish Council” was the “Social Jewish Self Help” committee, supported by the regional help committee located in Lublin. Moshe Rodsienek was the chair. They tried to help the poor by providing hot meals and free medical help. Yet, the resources they had could not meet the needs. The committee sat in Jacob Kornbloom's home, on Grabanover Street. Its kitchen used the house where Yitzhak Fogel's bakery used to be, on Proste Street.

In the spring of 1941, the Germans started to build army buildings quickly, mainly air force bases, in Biala and around it. Jews were employed, and the working condition were better than a year earlier in the working camps. It was clear that the Germans were planning an offensive to the east.

New regulations were imposed on the Jews such as: Jews were not allowed to leave their residence. The Christians were ordered to avoid any contact with Jews, because Jews are dirty, full of lice, and spread typhoid.

Jews could not ride carriages or wagons pulled by horses.

Jewish dwellings were confiscated, and they had to pay rent to an office specially established for that purpose. Rent was collected punctually, and the Jews had to renovate their homes and clean the yards and the streets.

|

|

The synagogue and the Beith Hamidrash were confiscated too. As refugees and other homeless Jews occupied these buildings, the “Jewish Council” had to pay the rent. When the “Jewish Council” deducted the costs of toilet cleaning from the 53 Rent, a German controller that came especially from Lublin

[Page 53]

slapped Jacob Aron Rosenboim, the chair, in the face. Still, the “Jewish Council” kept deducting the costs from the rent.

One of the new rules dictated that Jewish workers will get 20% less for their work than Christians. At the same time, the cost of food increased, and one kilogram of bread was now 6 to 8 Zlotys.

After Passover, the town filled with German soldiers going east. It was clear that they were getting ready for more bloodshed, the German–Russian war was about to start. The Jews hoped that this war would bring Hitler's end closer, but they feared the new struggle. Meanwhile, the cost of living increased, bread was now 12 Zlotys a kilogram.

On Saturday night, 21 of June 1941, the German army crossed the border to Russia. Hopes died soon, and the Jews feared the future.

During the first few weeks of the German–Russian war, Russian war prisoners were transported to Biala. When they went through the street, the asked for a piece of bread or for matches. After Moshe Gonski and Akiva Urberg were sent to Auschwitz (and died there) for giving some bread to war prisoners, nobody dared to help them. For the same 'sin' the Nazis arrested the Polish woman Byernatzka, but she was saved.

The Russian war prisoners suffered terribly in the German prison, but the Jewish war prisoners suffered even more. The Germans made every effort to identify the Jewish prisoners and kill them.

One working day, repairing the Brisk Road, a van full of Russian war prisoners passed the Jewish workers. One of them started shouting in Yiddish: “Friends! They are going to shoot us!” The Jewish workers recognized the son of Goldberg the shoemaker from Janaver Street.

By the order of the regional government, the “Jewish Council” set up a Jewish police, which the German called “The Jewish Police Service”. They were “decorated” with hats similar to those used in the Warsaw Ghetto. The police were responsible for order in the Jewish quarter; to keep people away from the main street of the quarter, Grabanover Street; to bring the Jews who did not want to work to the employment office and to maintain an appropriate level of sanitation in the quarter. Later, after the “Jewish Council” built a jail for tax refusers, the Jewish police were responsible for arrest and preventing prisoners from running away.

The following persons served in the Jewish police: Jacob Goldstein (commander), Heinech Bialer, Asher Rosenzweig, Motl Finkelstein, Moshe Preter, Haim Freidman, Fishl Lebenberg, Jacob Tokarski, Hana Leibson (a saddler from Vollia), M. Hartzman (secretary, the former accountant in Raabe's factory). Tzimeman, a refugee from Sulvalki, became the commander after Jacob Goldstein was shot.

In the autumn, the “Jewish Council” moved from Brisk Street to Grabanove Street, to the house of Jacob Kornbloom. The purpose of the authorities was to restrict Jews to a given area of the town.

One November morning, the German Police went out to the Miedzyrzec–Biala Warsaw road, and shot each Jew they happened to see. Among the murdered was Berl Jelaza, a flour Merchant from Biala. The shooting may have been connected to the order that restricted Jews to the Jewish quarter.

Many could not keep that law, and see their families go hungry. They tried to go out to make some living, risking their life. Indeed, some never returned, leaving their family in tears and sorrow.

On Christmas Eve, the “Jewish Council” was ordered to collect all the furs from the Jewish population. The office of the “Jewish Council” became a fur warehouse. Not all Jews hurried to give their furs to the Germans. A few chose to burn it or to destroy it in other ways, although, if caught, they could have been sentenced to death.

A few days later, the German police searched Jewish houses for more furs. This operation had one victim: a short fur was found under the coat of one man, probably mentally ill, and he was shot.

News came, that in the occupied territories in east Poland, Jews were being tortured and murdered. Among the victims were Jews from Biala who left in 1939, and considered as survivors. Sara Cohen (from Preter family), who returned from Slonim, brought the news about the terrible slaughter the German did to the Jews. This was the fate of Moshe Orlanski, his wife and their children, the husband of Sara Cohen, and others.

The town was full of German offices, and each one of them dealt with Jews. The fate of a Jew that these offices were interested in him was bad.

On Pilsudski Street, there was a station of the SD (the security services). Its commanders were two SS German and Glat. On top of the “presents” they demanded from the Jews, they ordered the “Jewish Council” to report what Jews were thinking and talking about. The “Jewish Council” tried to avoid reporting. When the pressure on the “Jewish Council” forced them to give a report, they said that the

[Page 54]

Jewish population worries about the coming winter, how to get survival supplies such as potatoes, fire wood, and so on. When the SD people heard the report they started shouting: We know: the Russians have reconquered Minsk, Vilnius, and Riga, this is what the Jews are talking about. They sent the “Jewish Council” back after beating them.

In the German gendarme was a man by the name of Apple. He probably was a carter before the war, employed by a Jew. He spoke good Yiddish, with juicy curses. The Jews called him “Yankl Face”. He used to pick on Jews, and every day he caught one to beat up. If he found a piece of meat in a Jewish house, he would make a real pogrom there. He would break everything he could lay his hands on, and beat up all family members. When the Jewish shoemaker Baruch Freiner, who was friendly with him, asked him: “Apple, what do you want from us? He used to answer: “I do not understand. You are beaten and killed and you are still here?!”

In the gendarme was a Polish police corporal by the name of Derwantzki, who enjoyed a special status because he spoke German. He had ways of blackmailing Jewish traders. He used to visit Jewish homes, but his demands could not be satisfied. And after he took everything, he handed the Jew to the gendarmes.

The defense police, located on Grabanover Street, used to scream in the middle of the Jewish quarter. Two were particularly cruel: Peterson, whom he Jews called “the yellow murderer”, and a stupid person whom the Jews called “Pesil”. The defense police had a smithy in the new market, and if they took a Jew to work there, they would treat him in such a terrible way that he would not forget it for weeks. When these two were on the street, the streets emptied immediately.

The defense policemen would break in at night, rape women, and rob the house.

Next to the regional administration was a special police, named “special services”. For a while, Gzimek was their commander. They gave the Jews a lot of trouble. They used to come to hunt people for work, and while doing that hit and harmed many.

The agents of the criminal police were also after Jews. They knew who is involved in trade, and blackmailed them. Agents Constantin Baldiga, Wolanski, and Golencyovski in particular. In 1941 /2 Baldiga shoot to death Weisberg the carpenter (son of Hanan the carpenter) and a young Jewish refugee from the former east Poland.

The Polish police also bothered the Jews nonstop. Jews had to bribe them to keep away from them; for the Germans, Jews were always guilty, and, after all the confiscations, they had next to nothing. Yet the Polish police officers knew exactly where to search.

The clerks from the regional administration constantly asked the “Jewish Council” for expensive presents. They always promised that no new decrees would be issued, but they themselves planned the new ones. The “Jewish Council” members knew their promises were worth nothing.

The Gestapo caused the least of the problems for Jews. They did not kidnap Jews for work, and did not come to beat up Jews. The Gestapo did contact the “Jewish Council” to take its last coins. Thus, the “Jewish Council” was always in deficit. Some Jewish artisans got a lot of work from the Gestapo. The Gestapo set up a tailoring workshop, where the brothers Nahman and Joel Subman, Meyer Rietz, and Aron Wolkowitzki work regularly. The Gestapo regularly employed the shoemakers Baruch Freiner and Nehemia Dorfman. The Gestapo supplied the materials.

Once in a while, these employees got some information from the Germans. The used to share it in secret with people close to them. They knew who had been put in Jail in Raabe's factory, or who had been shot to death in the forest.

One of the first Gestapo prisoners was Michash Hofer, the pharmacist. It seems that the Gestapo itself did not know the reason for this arrest, but did not want to set him free. Hofer used to spend the days in town, but at night had to return to jail. After the Gestapo took all his most expensive belongings, and after many months, he was released.

1942

By the beginning of 1942, the Jews of Biala were depressed, desperate, and without hope. It was their last year in their hometown. Their life became harder before the final deportation.

One winter, in late afternoon, the “Jewish Council” was informed that the defense police had put two young men who worked there in the cellar. In other words, they were sentenced to death. One of the men was the son of Hanan Reich. The police officer who put them in the cellar claimed that he saw them sawing a piece of wood to take home. The “Jewish Council” tried to save them. The police demanded 10,000 Zlotys, a fortune. Still, the money was collected and handed over, but only one young man was set free. Reich had already been shot and died.

[Page 55]

Everyday, Christians reported about dead Jews lying behind the town. Germans who happened to meet them had shot them. The worst was the gendarme Leon Bush, an ethnic–German from the Posen area.

Next to the church of Vollia, Gendarme Bush killed the boy who worked for Liptche Adelstein, the butcher. A few weeks later, on Shidorska Street, he shot to death the wife of Pinie, the bagel baker, from Miedzyrzec Street.

On the first week after Passover, ten Jews were arrested. All had been punished in the past for breaking Nazis rules. They spent the night in the Polish police station, and the next morning were taken to the Jewish cemetery on Janeva Street, where they were shot. Among the murdered were: the butchers Yurberg and Adelstein, the Sulvalki refugee Bernstein (the brother of Osip Bernstein the photographer), and others.

Similarly, on a June evening, the Polish police arrested Jews and the Gestapo shot them in the morning in the Vulka forest. Among the murdered were: Haim Freidman (nicknamed Beznosek [nose–less, O.A.], Nahum Tenenbojm's son in law, and Jacob Goldstein, the commander of the Jewish police who had been arrested a day earlier by the gendarmes.

Young Moshe Lichtenbojm (the grandson of Leib Mednick) was among those arrested in the Polish police station. He was arrested because he answered back to a Christian woman who insulted him. His parents, who saw the evening arrests, understood that an execution was planned. They did everything they could to free their son, but to no avail. One can imagine their anxiety when they had to return home when the curfew started, without their son. Early next morning they went out to the street, and heard that indeed, all prisoners had been shot, but their son stayed in the Polish police station. Overjoyed, his mother became hysterical. The redheaded police officer, Peterson, had arrested him; the Jewish policeman Moshe Preter knew him. Preter begged Peterson to free Moshe Lichtenbojm, but he refused. It seems that he just wanted Lichtenbojm to suffer, because he asked the Polish policemen to put him in a separate room when the Gestapo come for the others. Thus, with the others he agonized through the night not knowing that he will be saved. Indeed, he said they knew they were going to die, and spent the night confessing.

Meanwhile, Jews from Janeva were killed in Wulka Forest, among then Leibl Rodsinek from Biala, who tried to save Janeva Jews. A Christian woman, Konopka, was supposed to help him, but actually betrayed him.

Shooting became more frequent. All the Jewish prisoners in Lublin were shot. The Germans did not even cancel the discussion of their cases in court. The case of Noah Weinstein (from Prosheki village in Biala region) is an example of German cynicism. He was arrested for leaving his residence, and transferred from Biala jail to Lublin. His two daughters did all they could to save their father. They hired the famous lawyer Hofmakel–Ostrovski, who had connections with the German law system, for an unimaginable sum of money. Noah himself was not present in court; he was found not guilty, but never came home. The lawyer informed his daughters that he had been sent east.

In the middle of all this, the regional government sent the “Jewish Council” an order to provide a list of candidates to immigrate to Israel and to America. The “Jewish Council” did not advertise it, but the few who knew about it hesitated to register. The “Jewish Council” did not believe that the Germans would deal with Jewish immigration in the middle of the war. In general, Jews avoided putting their names on German lists. Since the regional administration did not repeat the order, the “Jewish Council” ignored it.

Most of the Jewish population worked, and a few artisans still had their workshops. On the other hand, only a few merchants kept their business. In the Jewish quarter there were still 20–25 small shops, most of them on Grabanover Street.

Under these conditions, it was only natural that smuggling flourished. The artisans who worked for the Germans or for the Christians and brought in basic products as part of their pay; the workers brought different things from their workplace.

The most commonly smuggled commodity was flour. Flour was smuggled together with the regular supply of flour with the food stamps. With these supplies, they also smuggled groats. The secret service knew about it, and because they were handsomely bribed, they made sure it continued. The bribery increased the costs of the smuggled flour and groats.

The “Jewish Council” got potatoes, a most important basic product, from the Polish “rolnik”. Yet, although the potatoes were supplied by government order, presents were still needed.

The butchers smuggled meat. This was dangerous, and the secret services did not support them. On the contrary, they were looking for them. Often, the butchers' fate was horrible. Meat was thus extremely expensive, and only a few could afford it.

The life of the educated Jews was very difficult. Except for the physicians, they had lost their economic basis. The transition to a lower social class was hard, especially as it was accompanied by beatings from the Germans. They sold everything that they had accumulated during years of work. The educated refugees had it even harder in the strange environment.

[Page 56]

They did not know anybody in the employment office, and could not get appropriate working positions.

A rabbi from Philipova came to Biala with the Sulvalkian refugees. After the death of Rabbi Moshe Utshen (died of typhoid in the winter of 1940/1) people turned to him with their Halachic questions. He had a reputation of a great scholar and of a person of the world. Yet, his influence was limited, because there was no synagogue or Beth Midrash in the Jewish quarter.

In the high holidays, there were places where several large Minyanim prayed. On other days, small Minyanim prayed three times a day in private homes.

There was no cultural activity in the Jewish quarter. Each person was completely absorbed in his own troubles.

The big “Tarbuth” library moved from Wolnosci Street to Brisker Street. Jacob Aron Rosenbojm, the chair of the Zionist Organization, devotedly guarded this treasure. The “Bund” library moved first to the home of Elijahu Hofman (Bobkes). He cared for it as best he could, but had to move it from his small home to the cowshed as the number of residents in his apartment kept increasing. Mrs. Liuba Tuchshneider ran a kindergarten on Grabanover Street. It supposedly had a permit from the supervisor of the Polish school system.

Many teenagers studied at home, aiming at taking their final exams after the war.

Despite the prohibition on reading newspapers, Polish and German papers were smuggled into the quarter. The Germans used loudspeakers to repeat the news broadcasted by the German radio. Children brought the news into the Jewish quarter.

Illegal publications came into the quarter sporadically. A person got a brochure from a Christian acquaintance and brought it in.

News Kidnappers

The cold, short winter days, quickly passed. People would sit at home at night, counting Hitler's failures. The Germans built a loudspeaker in the municipal park, broadcasting political news several times a day. The loudspeaker attracted the public, but the Jews avoided the risk of being found listening to the news.

Since there was a lot of interest in information regarding Hitler's failure, they sent the children to the loudspeaker, and they brought in some news.

Children stood in the bitter cold, their eyes and noses dripping, but their brains ready to absorb as much information as possible. At the end of the broadcast, when the children returned to the Jewish quarter, the adults were waiting for them with questions. The children, however, refused to answer. Each of them had his own audience, and only they would get the information.

I would like to write about one such audience circle. One 11–12 years old boy, Neta Osenholtz, specialized in collecting news from the loudspeaker in the municipal park. Before the war, he had attended both the Heder and the Polish elementary school. He was very thin, literally skin and bones, with burning eyes and a sharp brain.

He used to sneak out to the loudspeaker a few times a day. Dressed lightly, he listened jumping from leg to leg to keep warm, and take in the information. In the evening, he would repeat what he had heard and take part in the adult's political discussions. People were amazed at his ability. Being weak with malnutrition, his voice trembled, but he remembered in detail all the headlines, including those from the Far East, and presented news of places no one had heard of. His political knowledge and understanding were outstanding.

People that knew nothing about politics used to come to hear Neta. They came to see how such a weak boy “maneuvers” battle ships, airplanes, and other armaments.

When he was called home, he could not leave the political debates. His mother used to complain, “Well, Neta, I am busy breaking my head trying to find how to get some wood, or something else for the home, and you are doing politics?…”

When Neta went out of the room, people would say each other, “Well, go find such a boy among the Christians! No Christian boy knows so much about current politics.”

There were two other “new kidnappers” and talented politicians in Neta's information circle.

One of them was Haim Silberberg, the young son of Joel Silberberg the dentist. He was about 20 years old, unhealthy since birth, and a frequent a visitor to physicians. Just before the war, he graduated from high school, where he was one of the best students. He was exempt from forced labor because of his health condition. Yet he worked hard. He examined thoroughly the German newspapers, searched for hints and analyzed the information. His room was full of maps to follow the war. Occasionally his mother raised hell, fearing that if the police found the maps in a search, they would punished.

The second was Moshe Lichtenbojm, grandson of Leib Mednick, about 18 years old. He studied in a Heder, and general studies privately. Before the war, he had entered the family business, but was interested in politics. He, too, was well informed on the war fronts. His duty was to get the German newspapers in different ways, and to share it with young Silbeberg.

Moshe had a problematic leg since childhood, and he too was exempt from forced labor. Despite the exemption, he went to work in the carpentry of the ethnic–German, Krakovski.

[Page 57]

He had to pay few hundred Zlotys to get the job, but he did it on purpose: Krakovski had a radio, and Moshe was eager to listen to news from abroad. He got friendly with the ethnic–German, who had been a communist, and spent considerable time in his home. There he could listen to news from London.

He was also in touch with Jewish young men who served in houses of Nazi officers, who fully trusted them and gave them their house keys when they went on vacation to Germany. He used to spend the night in these houses, as they were the safest place to hear foreign radio broadcasts. Moshe was indeed full of foreign information. When he started sharing this information people did not let him go for hours.

Moshe did not want to rely on the information brought by Neta, and he did not have the patience to wait for Neta to return. He used to go to the loudspeaker in the park by himself. He succeeded at first, but later was beaten up a few times for his curiosity. After the restrictions on the Jews got tighter, you could find him at the gate of Israel Shaulkes, trying to hear something from the park. When the time for broadcasting came, Moshe used to sneak out of the workshop to listen.

The first expulsion

On Saturday, 21 Sivan, 5702, (6.6.1942), a rumor was spread in the city that all the Jews in Biala must leave the city. It was later learned that the “Jewish Council” had received an order from the district government, that all the Jews who are not employed by the Labor Bureau must be present at the train station on Wednesday, June 10, for transfer. The order applied to all the Jews in the district. All the country towns will be emptied of Jews and all the working Jews from the whole district will be concentrated in Biala.

The representative of the “Jewish Council”, Yaakov Aharon Rosenbaum, dared to ask the messenger Lipkov: Where will the people be sent? He replied: To the West. The representative of the Jewish Council asked again: We know that the Jews from the West are sent to the East, so why the Jews of Biala were so favored that they are sent to the West? Lipkov was embarrassed for a moment, but immediately came to his senses and said: “Don't you see the situation of the people in the synagogue and the other houses of prayer?” Rosenbaum replied: “Indeed, we would not object at all to the improvement of the situation of these people, but we know that the government is not interested in that, therefore, why do you care if these people die here?”

The messenger did not expect such an argument at all. And as he did not have any better answer, he muttered: “You, Rosenbaum, see everything in black colors; In this way, there can't be any cooperation with you”.

The “Jewish Council” began a vigorous action to repeal the decree and began to appeal to anyone they could. The Gestapo wondered that such “work” was not handed to them.

The “Jewish Council” learned that the decree was originated in Lublin, but they did not set a quota for the deportees. The district government was interested that the “Aktz'ya” (the roundup of the Jews before sending them to the camps) will be as large as possible.

After all the efforts of the “Jewish Council”, it became clear who would be allowed to stay and who would be deported. The right to stay was given to all those who had work cards as well as merchants and artisans, that were approved by the district government, along with their wives and children up to age 14. These women and children had to receive tickets imprinted with the seals of the Labor Bureau and the district government to prove their right to remain in place. Each deportee was allowed to take with him a package weighing only 10 kilograms. Anyone who disobeyed the order was subject to a death penalty.

The government instructed the “Jewish Council” that the entire “Aktz'ya” be run by it and by the “Jewish Order Service“. If they do not take control of the situation, the government will be forced to intervene, which will lead to undesirable results.

On the third day, the “Jewish Council“ announced the Jewish population about it through street ads, and set the collection point in the synagogue courtyard.

Already on Saturday, when it was realized that it is possible to be saved from the expulsion with the possession of a work card, many of the Jews invested many efforts in order to obtain such cards. And indeed quite a few succeeded, for large payments, to get these “cards of life“.

Singles who had been dating girls for several years and did not want to marry during the war, hurried to get married in order to save their brides from expulsion as married women. Fictitious weddings were also held to save the daughters of Israel.

There were those who did not find a way to be legally rescued and decided not show up and hide during the “Aktz'ya”. Many escaped ahead of time to the villages, to Christian acquaintances and to the nearby Mezerich. Those who decided to wander, began to prepare for the journey and packed their packages.

In the country towns of the district, the Jews fled to the forests. They did not even intend to be present for the transfer.

On Tuesday afternoon, the Ministry of Taxation showed its aggressiveness. Almost all of its officials, accompanied by policemen, raided the Jewish Quarter to collect old tax debts and even those not yet imposed by assessment for 1942. They demanded huge sums that had to be paid immediately, as in case of refusal they threatened imprisonment followed by a transfer to the transfer lots on the next day.

That day, Yaakov Malina went to the district government to settle some matter. At dusk, it was learned that Malina was taken out of the city by car and shot by the detective Baldiga.

These were tragic hours for the families. Neither the parents knew what to advise the sons nor the sons to their parents. No one had the courage to say to another: Stay home, do not go to the lot, because behind every command the word Death cried out!

On Wednesday, June 10, at 5 A.M., about 700 people had already gathered in the synagogue courtyard, wearing their best clothes and carrying packages. People flocked there from all over. The “Jewish Order Service”, which was enlarged specially for this purpose to 50 people, went from house to house

[Page 58]

and mentioned the obligation to be present at the synagogue courtyard. Those who belonged to the happy ones who remained in the city walked freely in the Jewish Quarter, where no inspection was carried out.

Representatives of the government came to the synagogue courtyard and watched what was happening. They released from the courtyard handicapped, sick and women with children, and announced that patients, who were unable to be transferred, would remain in their homes. Such a gesture, of course, reinforced the impression that the people were only being transferred to another city. The gesture convinced some of those who decided not to show up, to take now their package and go to the synagogue courtyard.

At 2 P.M., when the synagogue courtyard was already filled with Jews, the crowd was led by the “Jewish Order Service”, accompanied by several gendarmes, to the train station, where they were handed over to the “special service” of the district government. Some weak Jews were brought to the train in cars.

It is difficult to mention all the people of Biala who marched to the train. Some of them are engraved in memory: desperate and very exhausted marched the well-known and beloved Moshe Cava. The good-hearted teacher Hillel Meir Heiblum marched by him. In the rows also marched the merchant Yosef Gittleman and his family, Fintche Eidelman with his wife and child, Herzl Charni and his wife.

The Jews were forced to wait near the train until the next day, since, apparently, the “Aktz'ya” was carried out before the wagons have been prepared for the deportees. The “Jewish Council” brought them bread and coffee several times.

On the morning of the fifth day, a freight train arrived and at 11 the people were already locked in the wagons. The train moved from its place accompanied by an S.S. man and several Ukrainian guardsmen in the direction of Lukow.

The “Jewish Council” wanted to know where the Jews had been sent. The “Jewish Council” in Lokuw learned that the train had turned in the direction of Lublin. From the “Jewish Council” in Lublin it was learned that the Jews were sent in the direction of Chelm, while in Chelm they announced that the train passed through the city on Friday evening in the direction of Wlodawa. The last news was received from Wlodawa. From Wlodawa it was announced that they knew nothing and they asked not to be asked again such questions in the future.

Therefore, the information route was cut in Wlodawa. And since such an answer was obtained from there, it was easy to suppose, that the people in Wlodawa knew for sure what happened to these people.

The news of these continuous rumors became known to the district government. So, they tried to find out what the “Jewish Council” knows, but the “Jewish Council” replied: We asked the people to be present for the expulsion but we don't know where they were sent, you should be the ones who know about it and not us.

In fact, the “Jewish Council” finally learned where the people were exiled. It turned out that the last stop of their travel was Sobibor, 37 kilometers from Chelm, in the direction of Wlodawa. Sobibor was known before the war as a tiny station in the forest around Wlodawa, from which trees were transported.

Later on, they heard that many Jews had been brought to Sobibor and were kept there in locked wagons, on side railway tracks in the forest, for a few days without food and without water during the summer hottest days. Later on, the bodies of the dead were removed from the wagons and were burned there.

Weeks have passed and the thought of the displaced victims did not stop. It was obvious that the German government became the heir to the little property that the victims left in their apartments. The abandoned apartments were emptied completely.

The month of July passed relatively quietly, and then came the month of August that was full with bloody events.

On Monday, August 3, in the afternoon, Aaron Brodach was arrested by the district government. At the same time, the “special service” began searching for Menachem Finkelstein. When it could not find him, it imprisoned the chairman of the “Jewish Council”, Yitzhak Pizich, as a hostage, threatening to shoot him if Finkelstein was not found. After a while, Menachem Finkelstein appeared at the district government office, and Yitzhak Pizich was released. The news about the imprisonment of these two Jews made a strong impression in the city, because it was known that both of them had influence in the district government, and they had a strong support in the form of the two reporters, the engineers Davos and Neulinger. Indeed, relatives and friends always warned them of the consequences of contact with the Nazis, from whom they had obtained, from time to time, some kind of a favor for a Jew.

Immediately after the arrest of Aharon Brodach, the “special service” searched his apartment. During the search, his sister and wife Haya of the Feigenbaum family and her two sisters were arrested.

All that day, the families of the detainees made efforts to find out something about them, but without success. No one knew what to say, but everyone tried to calm down the others; They thought that this is nothing but a misunderstanding that will soon become clear. Thus, the day passed when nothing happened, and the time of the curfew for the Jews at 7 o'clock in the evening arrived. The families of the detainees were forced to return to their homes with mixed feelings of anxiety and anticipation.

The end was tragic. On the same day, all the detainees, women and men, were shot. People in the city whispered that in doing so, the Germans wanted to erase the traces of contact they had with these Jews, and that Neulinger, the reporter from Passau (Germany), had a big part in this murder.

At the midnight before Tuesday morning, suddenly the footsteps of soldiers were heard rushing through the streets of the Jewish quarter. As soon as dawn arrived, the wild roar was heard: “Mener Reus!” (Men get out). The entire Jewish Quarter was surrounded by gendarmerie, defense police, Polish police, Gestapo and Goring soldiers - pilots, all armed with machine guns and hand grenades. Gravanover Street was filled with men who were chased to the end of the street (towards the new market). Those who lingered on the way received blows from rifle butts. After a while, the Germans began to check the work cards. The check lasted several hours and all the men were released afterwards.

However, this almost “innocent” check claimed 19 Jewish victims, among them: Zalman Levrant, Yukel Listgarten, Friedman (from Poland's country towns, a former prisoner of war) and others. Many of those who came back alive from the check, were beaten there till bleeding.

[Page 59]

This “Aktz'ya” was conducted by the Gestapo soldier Peisker[b] and by the German gendarme Leon Bosch, who especially excelled in this bloody work.

The events in the city began to happen very quickly.

On Friday, August 7, the “Council of Jews” announced that by an order of the government, all Jews must leave their apartments and move to the small quarter, as previously planned.

The Jewish quarter that was formerly located between the streets: Gravanover and the alleys of the synagogue (except for a few houses facing the new market), Yanaver (only its right side), Froste (from the courts onwards) and Tzmentarna, will now be limited, as in a square box, between the streets: Gravanover, without the alleys of the synagogues (from Volnoshchi square to Froste), Froste (only the left side, from Gravanover to Pashkodenia), Yanaver (only its right side) and Pashkodenia, only its right side (from Yanaver street to Froste street).

In this narrow cage, there was a real suffocation, and people housed in barns and pens, because what choice they have in such a horrible situation.

The “ Jewish Council” tried to persuade the representative of the SD Glat, and he promised to work to repeal the decree, and indeed, it was canceled shortly afterwards.

In a conversation between the SD representative and the representative of the “Jewish Council” A. Rosenbaum, the SD representative said that this decree would surely be repealed, since other measures are being planned against the Jews. He didn't say what is the nature of these measures. However, as time passed, this mystery was solved.

On Monday, August 10, a rumor spread in the city that there were wagons near the train station, that will carry about 400 people from Biala to Lublin. The rumor has indeed been confirmed when people from the train station called all the German offices and asked to know when are the Jews taking off. Everywhere they received the same answer, that they knew nothing about it.

On Wednesday morning, August 12, a search was made for Jewish men by a foreign protective policeman, with the help of a Ukrainian militia. The detainees were brought to a collection lot in Volya. Among the detainees were many workers in government and German workplaces, and efforts were made to free them. The “Jewish Council” announced about this search to the SD Vida, and he went to the collection lot in Volya and released all the detained Jews.

Only a few hours passed and panic arose in the city again, as the search for men was renewed. At the same time, an order was received from the district government, that the “Jewish Council,” the “Aid Committee” and the “Disinfection Battalion”, should stand in the district government courtyard.

The reporter Lipkov went to those who gathered at this place. He ordered the women of the “Aid Committee” and the “Disinfection Battalion” to return to their homes and he immediately disappeared. A truck with a foreign police officer and several Ukrainians stopped there. The Jews were loaded on the truck and were taken to the train station.

There was despair in the city, as it was clear that with the exile of the “Jewish council”, the city was abandoned and the end of the tragedy was close and certain. They were sure there would be an immediate manhunt for the men, as there were still many missing for the number of people abducted in the morning search. And indeed, the search resumed shortly.

The abduction of 400 Jews was not easy because most of the Jewish workers were already in their workplaces. Therefore, the search continued all day, and when evening arrived after nightmare day, a dead Jew with a shattered head was lying in the gutter on Narotovich Street, and in the room was lying dead Bracha Adlerstein (the bride of Moshe'le, the bartender), who did not let a Ukrainian, one of the participants in the “Aktz'ya”, to rape her.

It was later known, that in the morning, the SD member Vida managed to free the Jews because the one who was in charge of the “Aktz'ya” was not in place but when he returned to the collection lot and saw that they were released, he ordered to detain them again immediately. He went to the German offices and presented to them, apparently, his power of attorney to carry out the search, and again he encountered no disturbances. On the contrary, they assisted him.

At 9 P.M., the freight train left for Lublin, carrying about 400 Jews inside the locked wagons, including most of the members of the “Jewish Council” and the “Aid Committee”.

Here, apparently, the “other measures against the Jews” that were mentioned earlier by the SD member Glat, began to be in force. First, they got rid of the “Jewish Council”, which, although it usually brought them gifts, at the same time this “Jewish Council” was too active and demanded too often to repeal various decrees. They also dragged the members of the “Aid Committee” and other institutions, thus helping the foreign protective policeman to fill the quota of abducted Jews, who had to be brought somewhere.

In August, the member of Hashomer Hatzair in Biala, Godya Steinman (the youngest daughter of the well-known Hebrew teacher Yaakov Steinman) was arrested. It was said that this talented girl was engaged in illegal activity and that messengers from the movement met in her apartment. The Gestapo arrested her following the imprisonment of a Polish railway worker, who was arrested on a train after illegal literature was found in his possession, and it is believed that he gave Godya's name and address. She spent a short time in the cellars of the Gestapo prison. The experienced killers seem to have realized that they will not be able to extract any information from this weak-bodied girl, despite the tortures she is going through. The Jewish tailors who worked there, heard about the torture she suffered there, and it was even learned from them that they had taken Godya Steinman out by a car to an unknown direction and there she was shot.

[Page 60]

At the same time, Galika Lichtenbaum (the daughter of Leiba Madenick) was arrested and shot by detective Baldiga. It is rumored that this was caused by a popular Germany, from which Galika demanded a repayment of a debt.

There was a panic in the quarter every evening because of rumors that at night there will be a search for men. Each went to sleep in his own workplace, leaving his wife and children to their fate.

The German extermination machine was already in full intensity at the time, and in the early stages of the extermination of the Jews, it made an effort to concentrate the Jews, in order to facilitate its work.

The military government informed the Jewish workers that anyone who wanted to work for it must stay in barracks under German supervision. The military government also began to provide food for its Jewish workers. The Jews did not want to lose their jobs and therefore had to agree to it. Every day in the evening one could see such a spectacle: the workers came to their homes from work only for a few moments, and immediately gathered again in the courtyard of the synagogue, where they were held in a military order and marched to the barracks. Anyone who wanted to spend the night at home, was hit the day after about forty blows with a stick.

Only on Sunday would the workers be released from the camp to see their families.

In the meantime, one of the 400 exiles in the direction of Lublin, the former prisoner, Grossman, returned to the city. A new picture of the tragedy unfolded from his words.

It was learned that the 400 people had been brought to the Majdanek camp, a few kilometers behind Lublin. There they received camp clothes to put on, but immediately afterwards, an order to return their clothes was received. Officials from the train management came and selected from among them about 350 people for the construction work of a new train line in Golomb, between Demblin and Pulaw, in the Lublin district. In the Majdanek camp remained about 50 people, most of them were old people, among them: A. Rosenbaum, Yitzhak Pizich, Moshe Rodzinak, Moshe Chaim Wiesenfeld, Israel Bialer, Shmuel Kreiselman, Yaakov Shlomo Zeidman, Yaakov Wolwell Herschberg, Berl Goldberg (pharmacist), Hanan Weisberg and others.

The work at Golomb was done in unbearably difficult conditions. Hard work, poor and little nutrition. For every slight negligence they would have been shot dead. Among others who perished there: Fishel Kantor, Eliezer Lerner and Blumenkrantz (the son-in-law of Yukel Listgarten).

Near Rosh Hashanah, almost all the Jews returned from Golomb.

The wives of the expelled members of the “Jewish Council” began to beg for the return of their husbands. The German officers promised them to fulfill their request, but the promises were not fulfilled. In the meantime, Eliezer Tselniker was appointed as the new chairman of the “Jewish Council”, and he, along with several remaining members of the “Jewish Council”, tried to carry out some action.

An order has been issued that on Saturday, September 19, that the “Jewish Council” of Biala, Yanaba and Konstantin, will appear before the SD representatives.

By Saturday afternoon, they already knew the results of this “visit”: The “Jewish Council” in Biala was required to collect from the Jewish population a few kilograms of gold. The reason was: thanks to this gold, the SD would be able to protect the Jews of Biala from the government. The “Jewish Councils” of Yanaba and Konstantin were informed that by Friday, September 25, all Jews in these towns must move to Biala.

On Tuesday, September 2, the SD member Glat invited the wives of the two members of the Jewish Council, Pizich and Rosenbaum, who were constantly urging him to return their husbands from Majdanek.

When these two women entered to SD member Glat's office, they found there the new chairman of the “Jewish Council”, Eliezer Tselniker. In his presence, he asked the women how much it was worth to them to pay for the release of their husbands because there was a possibility of their release. The women replied that their husbands were worth a great deal but unfortunately, they did not have large sums of money that they could pay for their release. The women tried to convince him to bring back all the Jews of Biala, but Glat did not want to hear such an offer at first. Finally, after prolonged pleas from the women, he agreed to try to help with the release of all the Jews. In return for this help, the women undertook to pay him a sum of 45,000 gold coins. He emphasized that the money should be transferred to him as early as possible, as he would probably have to travel to Lublin on Saturday or Sunday to transfer the gold collected by the “Jewish Council”, and meanwhile he could start talking there about the release of the people. In doing so, he remarked that everything should remain a serious secret, that if not, the women will be responsible to their lives.

On Wednesday, the first groups of Yanaba and Konstantin Jews were seen. Wagons loaded with Jewish families flocked to Biala. In Yanaba remained a small group of Jews who worked there in “Vigoda”.

Some of the 3,000 displaced Jews lived with relatives and acquaintances, and some remained for the time being with their packages in the street, in the open air.

On Thursday evening, Glat visited in the quarter. He promised to provide apartments for the displaced, and for the time being ordered the baker Yitzhak Pratar to distribute bread to the refugees and promised him that on Monday he would return him the flour.

Glat saw there the women Boltsha Pizich and Chaya Rosenbaum, who had been waiting for him all day to hand him the money. He told them to come to his office at 7 PM.

The “Jewish Council” has already supplied the gold it has collected. It was impossible to know whether this quantity of approximately 2 kilos would be considered as satisfying in the opinion of the SD people.

At 7 PM the women were already in the SD office and handed over the sum of 45,000 gold coins. Glat reiterated his promise to the women that he would be in Lublin on Saturday and he hoped to be able to release the men. Meanwhile the curfew began and he gave them permission that allowed them to walk down the street during the curfew.

[Page 61]

It was clear to everyone that the expulsion was imminent. In the Lublin district, the expulsion encompassed all the Jewish settlements. However, the Jews of Biala did not assume that a total destruction was about to happen.

The county government has spread rumors that the expulsion is not intentional at all to the Jews of Biala and that only the refugee Jews from the small towns were intended to be displaced. The Jews of Biala believed these rumors, although they knew that the expulsion of the refugees will include also quite a few of the Jews of Biala. But they had a solution for that as well. They have learned a lesson from the previous expulsion of the Jews of Biala as well as from the great expulsion in Mezrich: they need to hide. Therefore, the construction of the hiding places was in full force. They did not save money for this purpose, and a hiding place was created in every house.

Those Jewish refugees from the towns, who were qualified for work, lined up at the Labor Bureau and demanded that they be given jobs. It was known that in the previous expulsion of the Jews of Biala, this was a matter of salvation. Hence, they did not save money to get a work card.

On Friday, the eve of Sukkot, there was a nervous and crowded traffic in the district. The closeness of the danger was felt everywhere. The panic intensified following the news that various officials had come to receive works they had ordered and had not yet been completed from Jewish artisans.

Throughout the day, the “Jewish councils” of Yanaba and Konstantin collected gold from their townspeople, and in the evening handed it over to the SD.

At noon, the workers of many workplaces came to pick up their clothes because they had been gathered in camps. There were talks of 7 camps that will be set up in the city: 1. At the firm “Stoag”; 2. At the firm “Tzaid”; 3. At “Ostaban”; 4. At the “supervision of the water farm” (the only camp where there will also be women); 5. At the airport; 6. In the military bakery; 7. Under military rule. The last camp will be the largest. In this camp, all the workers of the private firms who have a permit to employ Jews will also eat and sleep.

The Jews were divided into three types: one type –campers; the second type - those who prepared hiding places, among them were few that were about to hide with Christians. Among those who were preparing to hide were also campers, who did not want to part from their relatives; The third type were Jews who had no hiding place, or did not want to hide at all and were ready for anything.

The second and the final expulsion

On Saturday, the first day of Sukkot (September 26, 1942), at 5 AM., gunshots were heard in the Jewish Quarter, and it was clear that the bloody events had begun.

A. In the collection lot and on the streets

As it was later learned, the expulsion “Aktz'ya” began before 5 AM. When the gunshots were heard, there were already quite a lot of Jewish victims.

The “Aktz'ya” was attended by the Gestapo, the Defense Police, the Gendarmerie, the Polish police and Air Force soldiers, who surrounded the quarter at 10 o'clock at night.

As soon as dawn began the rise, they started the expulsion of the Jews from their homes and walked them to the “pig market”. There they were ordered to sit on the ground.

|

|

| Order for Jews to leave Biala |

They broke into houses in which the people were not in a hurry to open the doors. Like raging animals, the Germans entered the houses and brutally beat the people, and even used their guns and shot down casualties. Patients who lay in their beds and could not go to the collection point were shot in their beds. The SD member Glat ordered the man from the “Jewish order service”, Heinech Bialer, to enter a Jewish apartment in Haim Gotel's yard, on Froste Street, and check if there are any Jews there. Bialer entered the apartment and found Jews there and told them to hurry. He informed the SD man that he did not find any Jews there. However, Glat did not believe him and entered the apartment and found several Jews there,

[Page 62]

who have not yet been able to hide. He immediately went outside and shot Bialer right on the spot.

The Jews on the street, who went to the collection point, were severely beaten, some of them were even shot.

The three Grodner sisters came to the street with their little brother and hurried to the pick-up point, and here the protective policeman, Patterson, appeared in front of them, and when he saw the younger sister, an incredibly beautiful girl, he said: “It's a shame to take a girl like that to Mezrich, it is better that she stays here”. A shot was heard and the girl staggered and fell to the stone floor with a shattered head. The two sisters with the little brother were hurried to the collection point.

In the collection lot, the Jews sat depressed and terrified. At every moment, the Germans chose a Jew, led him aside and shot him dead. A long mass grave was created near the house of the Christian Shidlovsky.

Jewish blood flowed through the houses, on the streets and in the collection lot. There were dead bodies of Jews everywhere.

The protective policeman Patterson, the gendarmerie Bosch, and the Polish Police Chief Kukzewski raged with extremely cruelty.

Many hiding places were immediately exposed by the executioners. Those who were hiding were led to the collection lot while being beaten aggressively, which caused some of them to fall.

When there were already enough Jews in the collection lot, they began select people who were capable to work for the camp in the airport, and for Malashowicz (the former Polish airport, near Terespol).

Terrible spectacles took place on the lot: the people were beaten to death constantly and women and children were shot for no reason.

Here they brought the young man from Sarotsek, Zusha Goldberg (a friend of the above-mentioned Godya Steinman) who worked all the time for the protective police, and there they were very pleased with him. Only a few protective cops, that were led by Patterson, resented him for not letting them steal from the warehouses. It is impossible to describe the path of torment that this young man went through until he died. He was beaten and wounded with poles, then his eyes were punctured and again he was beaten aggressively, tortured and abused.

The young man withstood all these tortures with heroism, did not ask for mercy, only hurled harsh words at his tormentors: “You are heroes only against defenseless Jews, but the world and Jews within it will still show you your heroism when you will be defeated in this war!” This infuriated the torturers even more and they intensified the torture until he died.

The people at the collection point were demanded to hand over the money and jewelry, or else they will face a death penalty. Since they assumed that they were being sent to the extermination camp in Treblinka, they did not take anything with them. Later on, they regretted it, because the Jews were loaded on wagons and were drove to Mezrich.

However, only the elderly and children were seated in wagons, the young people were ordered to line up and walk to Mezrich, and only when many empty wagons were left, the young people were loaded on them as well.

And so, wagons full of oppressed and frightened Jews flocked, without them knowing where they were being led. At the end of the Biala district, in the Voronezh forests, many Jews removed from the wagons, they were led to the forest and were shot there.

The victims of the streets of Biala, and the bodies of the dead of the houses, who were thrown out of the windows, were led by the Christian municipal workers to the cemetery. After lying there for a few days, they were buried by the Christian workers.

At the Jewish hospital, where about 15 patients were hospitalized and two compassionate nurses treated them and did not want to leave them - the Gestapo broke in and ordered the nurses to give the patients good food...

The Christians took advantage of the darkness of the night and took over the houses

|

|

| Jewish cemetery at the time of the Expulsion |

[Page 63]

|

|

| Christian population ordered to hand over to the Gestapo goods plundered in the Jews quarter |

of the Jews, and took everything they saw. They also stripped off the clothes of the dead bodies that were rolling in the streets.