|

|

|

[Page 447]

Yitzhak Lichtenstein

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

In many of the artistic centers of the wider world I have met Jewish artists who have told me about the life and works of their teacher Yuri (Yehudah) Moiseevich Pen, the head of the art school in Vitebsk.

The first person from whom I heard about him was the artist Marc Chagall. In 1911 we were neighbors in La Ruche, that beehive of artists in Paris on the Passage Dantzig near the Porte de Versailles.

Yehuda Pen was born at the beginning of the 1870s [trans. note: Pen was born in 1854] in Novoalexandrovsk, in the Kovno Gubernia. He received a strictly religious education. From childhood on, he always followed his inclination to draw. People considered that sinful, but after much struggle he was allowed to enter the Petersburg Arts Academy and later to open his own art school in Vitebsk. Hundreds of young people studied in his school, among them many from the surrounding areas. Pen was very interested in the Jewish character, the Jewish environment, with Jewish customs, and especially with characteristically traditional Jewish picturesqueness. He created works such as “The Difficult Issue,” which shows a simple Jewish man who struggles over a sacred text, a Jewish woman with a Yiddish prayer book, so characteristic of our mothers and grandmothers. Pen's large painting “The Divorce” shows a whole gallery of different Jewish types in a dramatic scene of Jewish life. His painting “The Matchmaker” typifies his work, as do his paintings “In the Front Room of a Prince” and “A Letter to America”—and his characteristic “A Mother's Letter,” full of longing and loving sorrow. Open handles all of this in his realistic-romantic fashion.

[Page 448]

He knew how to work like a dedicated artist of his time.

The artistic world soon began to hear quite often about that Jewish place, Vitebsk—not only to hear but to see Vitebsk themes at art exhibitions, especially those of Chagall.

Our Jewish group in the Parisian art world derived great joy from the little shtetl motifs on the walls of the big-city salons. And Chagall was not the only Vitebsker in Paris. There wer also Abel Pann, Ossip Zadkine, Oscar Miestchaninoff. Each of them had his own style, and their works had nothing to do with Vitebsk, as if they had never been there. One cannot say that about Chagall and Yudavin. They would emphasize the little shtetl and even use the name Vitebsk in their titles.

It could be that sometimes Pann played with aspects of Vitebsk. But this did not amount to a characteristic expression. It was, in a certain sense, a faded reflection. Paris affected Pann far differently than it did Chagall.

Actually, Chagall was also influenced by the Parisian school, but far differently than the other artists from Vitebsk. Zadkine and Miestchaninoff had nothing at all to do with their home town, but in Chagall one can always find a certain nostalgia for Vitebsk. In Pann, only a pale reflection. But Zadkine and Miestchaninoff are far from those who remember their old home. They are artistic personalities who entirely freed themselves from anything like a Vitebsk motif.

Chagall did not only depict a type of longing. He celebrated, lamented, and, in a certain sense, even glorified. Just as Belz is in the popular song “Mein Shtetele Belz,” so was Vitebsk for Chagall.

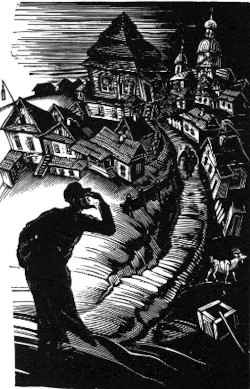

In 1912 one could see in the Parisian “Fall Salon” Chagall's macabre conception in a painting with a remarkably mysterious atmosphere. There is a crooked street with a corpse in the foreground. Glowing lights twinkle around the dead man in the gray, crooked street. A fiddler sits on the roof of a house with a shoemaker's sign—one of those laconic signs: a shoe on a stick. A street sweeper sweeps the street, while frightened people run in panic…In Chagall's macabre conception of a dead man in a

[Page 449]

small-town street, the whole world could see a Vitebsk motif. The frightening detail on the crooked roof and the little street with the corpse, the grotesque Jew with the fiddle revealed a kind of paraphrase of what I later found in the Latgale shtetl of Rezekne where I happened to be in the 30s. I went there to examine a neglected Jewish spot—and I found there traces of a Chagallian source. I found there echoes of Chagallian Jews standing on the heads of other Jews. I even detected the Jew with the fiddle. I found skulls of clay figures stuck onto Latgale shepherds. There were horses with riders. Sometimes the rider was a little person with a large pipe, while sometimes riding on the horse was a dog or even a grotesque bird. And sometimes it happened that sitting on the little man who was riding the horse was a dragon. There were baked clay whistles that one could buy at the fairs between Rezekne and Vitebsk, which was not far from Latgale.

This interested me greatly. I began to look around. I discovered that the Latvian art department had assembled everything that could be found in the Latgale fields. I later sought out that department and explained what I thought about the whistles. They showed me a huge collection. They allowed me to choose ten of these clumsy but original examples. I brought them with me to Paris, and I often thought of them as characteristic examples of something that had influenced Chagall and Zadkine.

These two artists, you should know, were two very different personalities. But whenever they are set next to each other—how can one say it?—one can say that they had similar sources.

Actually, it is a little more complicated. But the figures of the Latgale shepherds underscore my idea.

Ossip Zadkine was a sculptor, draftsman, engraver, and water-color painter, a bold artist of great ability. He had a strong inclination to innovation. He was born in 1890. Around 1906 he came to England and studied in the London Regency Street Polytechnic. Later, in 1909, he was already in Paris. He spent a half year in the local art academy. In 1911 he began to exhibit in the Parisian “Fall Salon.” At that time Zadkine

[Page 450]

lived in La Ruche, a neighbor of Chagall. But they did not seem to come from the same city. I had then come to La Ruche and I remember it well. A year later, already in Jerusalem, Abel Pann told me that Zadkine came from Smolensk, but he also knew him from Vitebsk, where he grew up. Pann himself was from Kreslavke, born in 1883. His family name was Pfefferman. He came from Pen's Vitebsk art school via Odesa to Paris, where he took part in humorous journals and participated in various exhibitions. Around 1913 he came to Eretz Yisroel and became a teacher at the Bezalel art school. At the time of the First World War he was in America. He returned to Eretz Yisroel and settled there, where he produces lithographs, mostly on Biblical themes in Israeli styles.

At the same time, when Zadkine and Pann lived in Paris, another Vitebsker arrived—Oscar Miestchaninoff. Around 1911 he finished up at the Paris Art Academy and began to exhibit in Parisian salons. Miestchaninoff was not only a sculptor, he was also a true collector of art. He was among the first to recognize such artists as Chaim Soutine and Amadeo Modigliani.

Miestchaninoff was also greatly interested in older art and he owned fine examples of antique and characteristic examples of modern art. The fact that he was so interested in Soutine early in his career was fortunate for us, for it allowed him to collect a number of Soutine's early paintings.

Oscar Miestchaninoff was a gifted artist. His sculptures are in many museums. After 1944 he was in America. He was among those who took part in few exhibitions. He belonged also to the Jewish artists who were interested in the art center of the Jewish Cultural Congress in New York. He exhibited regularly in the annual show of the art center, which was founded in 1948.

The proclamation of the State of Israel and the revival of Jewish art in America were for Miestchaninoff signs of a Jewish renaissance.

I well remember that he could not rest until he had engaged me in a conversation about our shining artistic interests. And I remember, because it was interesting

[Page 451]

|

|

[Page 452]

from a variety of standpoints, and the opportunity was also interesting, because Miestchaninoff seldom showed his own feelings. He was more of the silent type. For me it was extraordinarily interesting to learn about the continuity of Jewish feelings in such an artist. I had often thought that Jewish feelings were entirely subsumed by international concerns. There were plenty of examples of this. This is not the place to discuss them, so I just want to underscore my happy surprise. And Oscar Miestchaninoff was the cause.

The writer Moyshe Broderzon used to tell me often about the artist Lissitzky, about whom he had beautiful, romantic memories. It was a great pleasure to hear how a writer received such joy from an artist.

Lissitzky's name was actually Lazar, but he used only the first initial of his Yiddish name, so he was known as El Lissitzky. He was born in 1891. He was a student of the Russian painter Malevich. Between 1922 and 1925 he lived in Germany and Switzerland. In 1925, together with the artist Hans Arp, he published an art book called “The –Isms of Art—1914-1925.” As one can see from the title, this was a work about the various “Isms” in art from 1914 to 1925. In this art book, he reveals his artistic self. There he stresses his constructive character, a kind of connection to architecture.

In the 20s, Lissitzky devoted himself largely to graphics. He would ornament books, make posters, concern himself with typographical innovations, book displays, and photomontages. At that time Lissitzky issued “Pro dva kvadrata” [“About Two Squares”}, which was also published in Dutch. In modern art, the Dutch art movement was recognized as an important branch of abstract expressionism and of ultra-modernism in Constructivist Art. And Lissitzky must be considered a Constructivist. He can also be included in other “Isms” that have a connection with architecture.

Lissinsky is now in the Soviet Union. Also active there is Shlomo Yudovin, the graphic artist of remarkable works on Jewish themes.

Shlomo Yudovin was born in 1894 in Beshenkovitch, a small shtetl near Vitebsk. His parents soon moved to Vitebsk. From childhood on he showed a talent for drawing.

[Page 453]

|

|

In 1908, when he was 14 years old, he began to study in Pen's art school, where he remained for only a short time, not more than two years. In 1910, Sh. An-ski took him to Petersburg. Yudovin there went further in art school.

In 1913-1914, Yudovin participated in An-ski's folklore expedition. As part of that expedition he travelled to Jewish cities and towns and collected interesting material about Jewish life. The images he collected greatly influenced his important artistic work.

From 1916 until the present, one can see Yudovin's work in our important art exhibitions. And he uses interesting themes from Jewish life that adorn books by Jewish writers.

In 1918, after the Bolshevik Revolution, Yudovin returned to Vitebsk, where he remained for five years, in 1923. In 1919

[Page 454]

he organized in Vitebsk a special exhibit of Jewish folk art. In 1926 the Vitebsk city council published in White Russian an album, “Vitebsk in Engravings,” containing Yudovin's Jewish motifs.

In 1927, the Leningrad Art Academy invited Yudovin to participate in the exhibition that it had organized. Everyone considered his shtetls to be an important contribution.

Yudovin belonged to the modern graphic artists, who regarded their work with professional concern and used rich sentiment and clarity of form. His many works on Jewish themes show this very clearly. It is possible that Yudovin was perhaps for the most part the closest to the Vitebsk art teacher Pen.

Themes of Vitebsk can also be found in several other artists. But these are isolated themes, nothing more. Yudovin's woodcuts sharply portray the characteristic aspects of the city of Vitebsk, with its houses and its streets. Especially vivid are his portrayals of Vitebsk's Jewish characters. It was not for nothing that the critics said that his art carried a deep Jewish-national character.

In the last couple of decades, one could often see in various exhibitions in Amerioca the pictures of Binyamin Kopman. In these exhibitions one could see the interesting development of an aspiring artist. One could see the zig-zag path of a creative artist—from William Blake's biblical mythologizations of the Tanach to the romanticization of Daumier. And this was only one stage. Others came later, more zig-zags of creation in a sparkling era.

The artist Benjamin Kopman was born in Vitebsk in 1887. He grew up in Yekaterinoslav. Later, when he was 13, he returned to Vitebsk. He remained there a short time and then came with his parents to America. In the short time that he was in Vitebsk, he studied in Pen's art school.

In America, Kopman studied in the New York “National Academy of Design.” But he actually had nothing to do with the academic expectations of that institution. He was attracted to such artists as the French Expressionist Honore Daumier and the tragic Jewish Expressionist Chaim Soutine.

[Page 455]

Kopman had a restless intellect. His spirit could not be satisfied by his accomplishments. He would stop at one point, then change directions, all the while finding new outlets for his thoughts.

Kopman came to America in the first years of the current century. Modern art had not yet been Americanized. In 1913 there came something that could be considered an invasion of global modern art. This was the “Armory Show,” the ultra-modern exhibition in the armory on Lexington Avenue. The impression it made was remarkable and its influence was colossal—not only in New York, but in the furthest corners of America where there were influential artists.

And Kopman then lived in the mysticism of William Blake, of his “Anglicized” Bible—at least so it seemed to me when I first saw Kopman's paintings.

The group of painters from Vitebsk hold an important and prominent place in Jewish art. I seek artistic relationships among them. I think about their original influences. I find them in an original environment, the Vitebsk of their childhoods. Artistically their material is substantial. In a certain sense it was a good beginning for a creative continuation.

Yitzchak Charlash

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

Early in the morning of January 15, 1892, a ship made its way into the foggy harbor of Philadelphia. Formerly this ship had been used to transport oxen, but this time it brought from Liverpool hundreds of Jewish immigrants from Russia. Among them was a young man who bore “twenty dream-filled years on his back.” He had “a few German gold coins in his pocket, along with some addresses of landsmen in Philadelphia.” He came to America because in his homeland he did not choose to “serve the emperor.”

The young man came from Vitebsk–from a family of gravediggers, from cemeteries, from generations who belonged to the Chevra Kadisha. Their earnings came from the purification room at the old cemetery in Vitebsk. Consequently, their family name was Kobrin, from “kabren” [gravedigger]. The young man's name was Leibe, or Lyova (which became Leon in America) and he was his father's favorite son. In Vitebsk his father dealt in fish, stopping at lakes where Jewish fishermen worked for him. He was a well-off man, and his son was intelligent, with a heart full of “Weltschmerz.” He was attracted to Russian literature, and he dreamed of the redemption of the world and freeing of humankind.”

When Leon Kobrin came to America, he spoke only Russian (and already wrote Russian stories). He knew no Yiddish. “Yiddish Jargon was so foreign to him, so distant…” that the fact that he would be one of the progenitors of “some Yiddish theater” and on of the builders “some Yiddish literature” in America even he could not have dreamed of. When, for the first time in his life, he saw in New York

[Page 457]

|

|

[Page 458]

London's “Worker's Friend,” it was a huge curiosity in his eyes–a newspaper in “jargon”?

Actually, he knew he knew about Shomer and Blaustein's “jargonish” storybooks that were read by Jewish servant girls; he even knew that there were serious writers of “jargon,” but he had never read anything by them. The only work that he had read was Mendele's “The Nag,” but he had read it in a Russian translation that was published in “Vochsod.” And now here was a newspaper in “jargon” with such modern words as “palliative,” “revolt,” “class warfare,” “bourgeoisie,” with such spiritual and witty language as used by the “Crazy Philosopher” (Morris Winchevsky) in his “Battered Memories.” Such fine poems from the same Winchevsky, which were both revolutionary and sincere, made a strong impression on the young man from Vitebsk, who had always dreamed of being a writer in the language of Turgenev and Tolstoy, Pushkin and Nekrasov.

And so Leon Kobrin in America became a writer of “jargon,” something of which he could have had no inkling earlier. Certainly this did not come easily. Without knowing Yiddish, with no spoken tradition, without a Yiddish inheritance, without Yiddish literary influences, without a shaping environment, he naturally had to work very hard and suffer before he succeeded in taking hold of that “strange jargon” and making in into an instrument for artistic creation. However, his unconscious creative urge did not allow him to rest. The unwritten subjects tormented him in reality and in his dreams. The heroes who crowded his memory demanded actualization, and his need for an income urged him on: to a score of employments, including sewing shirts, making cigars, and making forms in a candy store. But Kobrin adapted. He struggled, and he wrote Yiddish. For this he adapted!

Almost a whole literature Kobrin wrote in the course of five decades of creativity. Hundreds of stories, numerous novels, more than thirty pieces with which he fed the Yiddish theater in America over two decades, hundreds of essays and newspaper articles, twenty or thirty volumes of translations that he and his wife Paulina Kobrin made of Tolstoy and Dostoevski, Chekhov and Gorky, Turgenev and Artzybashev, of

[Page 459]

Goethe, Shakespeare, Hugo, Zola, Maupassant. Surely not all of these works of Kobrin maintain their freshness, interest, and value fifty years later, but many of them have withstood the test of time. People still enjoy seeing “Riverside Drive” on the stage. The drama of “Ora di Bord” can still hold the reader in suspense, and from the chapters of volume “From a Lithuanian Shtetl to a Tenement House” can still give much pleasure. Especially–from a cultural-historical standpoint, Kobrin is one of the few figures who created a literature from chaos, actualizing people and characters out of dust–true creations ex nihilo.

This pioneering time with its literary creation story in Yiddish-speaking America has always been tied, as if by magic, with the creative spirit of Leon Kobrin. He always wanted to show what a wasteland Jewish America had been in those distant years of the gray dawn and how the pioneers had “with their blood and spirit shaped the foundation” for a Yiddish literature, for a Yiddish theater, for a Yiddish press, and especially for a Yiddish cultural life in this country. Two series of descriptions of this sort Kobrin put out in New York in the 20s: “The Memories of a Yiddish Dramaturge,” which was published in two volumes in 1925, and the “Pages from a Spiritual Jewish Life in America”, which Kobrin revised later in 1945, shortly before his death. He lengthened it and began to publish it in the “Tog” newspaper. The writer's death unfortunately ended the series. But the writer's widow took over everything that remained from this series and (in 1955) published it in book form with the title “My Fifty Years in America.”

This was an odd book. Actually, it only deals with Kobrin's first two years in America, from his disembarkment from the ship in January 10 1892 until his debut with a Yiddish story in the “Philadelphia City Newspaper” in the spring of 1894–but what a two years! That was the time when every day another thousand Jews came to this country from Russia. Modest merchants and businessmen, sedate, upstanding citizens, small-town paupers were there “in purgatory” transformed over night. People went around the streets like monsters in the gray dawn: with sewing machines on their backs and with stools in their hands. Jewish “Psalm-reciters” began to speak

[Page 460]

of “unions” and “strikes” and “scabs.” People sewed shirts and pressed pants and rolled cigars for two dollars a week. Girls from higher class families began to speak of the “social revolution.” Domestic middle-agers looked for “boarders”, who could not be “cockroaches.” In the lines at the “bosses,” where newcomers went to seek work, people crowded, spoke in Yiddish and in Russian, and also in English. Heaven and earth mixed together. And in the general confusion, a way was laid out for social-democrats, anarchists, trade unionists. Jewish intellectuals held fiery speeches and put out party-based newspapers. Yiddish poets wrote revolutionary poems. Jewish idealists built co-operatives and founded communes. This was the era that was described in Kobrin's “Fifty Years in America.”

A fantastic picture remains of the previous ninety years in America, as Kobrin describes in his book. Things that would be unbelievable in a normal time were the reality. Without tradition, without style, without discipline, driven by instinct or by need, behaved in eccentric ways. Their conduct–impulsive. Their movement----reflexive. As if everything around them was characterized by the grotesque.

Moyshe-Leib's Rivke at home in Vitebsk was “a woman with five skirts…as full of health as a barrel is with wine.” She lived prosperously with her husband, the wealthy grain merchant. She cooked tasty foods for their full meals. She was a leader; she prepared a fine place in the world to come; and in her free time she devoured storybooks in “jargon” that she would obtain from the hunchbacked book peddler. But in the course of time the crowd turned on the business of Moyshe-Leib, her husband. So Rivke with her husband, with their two children, with her mother turned up in America. Moyshe-Leib became a cigar maker, and Rivke joined the anarchists (the “commune”–as her mother said). She fought against “exploitation” and against the “damned trinity: religion, state, moneybags” and steeped both daughters–one 8, the other 6 years old–in the spirit of anarchism.

They sit by the table–as Kobrin paints the grotesque scene–and the children–two blond girls with braids and blue eyes, small, dressed in white–two blond dolls. All of a sudden

[Page 461]

Rivke's face lights up and she asks one of the blond dolls:

“Sophie, do you believe in God?”

“No,” responds the child.

“Why not, Sophie? ”

“Well, who created God? God has no parents, and without parents, no one can be created,” says Sophie in an childishly earnest way.

“And who believes in God?” continues Rivke.

“Foolish people and hypocrites who get business from the belief in God.”

“And who else, child?” Rivke goes on.

“All of the capitalists who want people to be foolish and to believe in God.”

“Why do the capitalists want that, Sophie?”

“Because foolish people are afraid that God will punish them if they ‘revolt’ against the capitalists.”

“And will you make a revolution when you grow up?” her mother asks.

“Yes, Mamma, for the commune, for the anarchist commune, Mamma.”

Enthusiastic and triumphant, Rivke is about to cry from naches and pride.

And then there is the tragic end of Comrade Jack Piotr Kropotkin. At that time–Kobrin relates–when a Jewish social-democrat had a child, people gave him the name of a famous revolutionary. Consequently, there was a good crop at that time of Karl Marxes, Bakunins, Lasalles, Chernishevskis, Perovskis, Zhelyabovs. But there were also some who could not wait until they had children, and they gave themselves names of famous revolutionaries. One such young man, a social-democrat, a Chasid named M. Zametkin, called himself Herbert Spencer. Another one, an anarchist whose name was Jack, called himself Jack Piotr Kropotkin. He was a young man who already had a bald head, was over six feet tall, with broad shoulders and a pair of powerful red paws, with a flat, obtuse face, with little ears.

[Page 462]

It turns out that this “consequential anarchist” loved a certain “Genossia,” but she did not return his love. She had devoted her maidenly attention on others. The loving Jack Piotr Kropotkin fell into a dreadful jealousy. In his heart he struggled strongly with this “barbaric” view of the woman as his property. And when he felt that he could not uproot her from the “Philistine petit-bourgeois,” he went into his room, turned on the gas, and departed this world.

Here the “divinely innocent”, sickly naivete runs through like a red thread through a score of descriptions of the “rank and file” of the mass of anarchists and socialists in the book. Such is the burning young woman who is inflamed and excited by M. Zametkin's lecture, so that she sobs and cries aloud: “Ay, ay. When will the socialist revolution come!” So, too, is the excited young anarchist who advises his impoverished friend not to hurry to buy a ship ticket for his brother in Russia, because today or tomorrow the socialist revolution will come and poor people won't have to buy tickets for ships at all…

And not only the “rank and file”. The leaders, too, that time were eccentric, hysterical. The famous M. Zametkin came from New York to Philadelphia to deliver a talk about Tolstoy's “Kreutzer Sonata.” He spoke Russian, and naturally he translated each of Tolstoy's words with a revolutionary meaning. Kobrin thus describes the “Chekhovian impression” that the then legendary socialist speaker made on him:

“He had his coat over his shoulders, one arm in a sleeve and the other free. He went back and forth on the stage with a clog on one foot and a bag on the other. He flamed and protested against the capitalist system. From time to time he gave a nervous pull to the loose sleeve on his arm or a tug to another part of his clothing–mostly to the back of his pants…Everything in him spoke-even his clothing flamed and protested…”. In his voice and in his whole manner of speaking there was something that led his listeners to hysteria. He spoke in a warm baritone, which from time to time took on a deep bass sound, especially when he wanted to emphasize something…”

[Page 463]

Then, in a bass undertone he would say, “Yes, yes, my dears. Yes, yes.”

When after the lecture–relates Kobrin–people would go for a glass of tea, Zametkin had both clogs on his feet. But the coat, with one arm in the sleeve, stayed over his shoulders. And the night was cold and wintry. When someone asked Zametkin why he wore clogs, he answered, “Calluses, my dear, made my shoes. New shoes, my dear, on their third day–such calluses that my eyes pop out of my head!…Nu, so I had to speak today, so I put on slippers. Otherwise my calluses wouldn't have let me speak today.” And he adopted the lowest notes of his baritone: “Yes, yes, my dear. And another thing. We have to quickly bring to a close the current capitalistic system.” In the socialist system, Zametkin offered, people will make shoes from fine leather. They'll be well made and won't cause calluses.

The young man understood–says Kobrin–everyone understood that Zametkin was right: people needed the revolution quickly! And later on as everyone was singing, in the stillness of the cold winter night, the leader's voicer rang out like the voice of a Russian deacon: “Stand up, rise up, you working folk.”

Not less, and possibly more fantastic is Kobrin's description of the eccentric, self-willed union leader Yosef Barondess. There he stands on a Shabbos afternoon in the Valhalla Hall on Orchard Street and delivers a talk. The hall is packed. People are standing head to head. They are all newcomers, modest newly arrived merchants and businessmen who have now become “shop workers.” Quietly, in a distracted tone, measuring his words, Barondess speaks to them in ringing tones.

“Workers, there in our home, in accursed Russia, with its czar, you dealt with the Gentiles in the market and suffered agues with kosher threads…It seemed, therefore, that however little you received there in the ‘sweat shops’ from your ‘cockroach existence,’ it was quite a lot. Let me tell you that in America, they call this ‘starvation wages.’ You could work ten times as much If you would be donkeys! You are in America, not in Shnipishak

[Page 464]

and not in Tuneyadevka. And not in Blotevka. Here you can live like human beings! Eat like human beings! Dwell like human beings! Dress like human beings! And look like human beings, not like beasts, like oxen, like donkeys.”

The speaker takes a drink of water from the glass on the table near him and continues:

“Nu, how can you achieve all of this? What I mean is–how can you escape being beasts of burden? Only if you are union people, my dear Jews, if you are united in your unions! Jews–my dear Jews–” a tear appears in is speaking voice–“I work and work. I work for you twenty hours a day–do you hear? Twenty hours every day I work, Yosef Badoness, for you. Why do I do this? So that you should be proper union members with better working conditions, so that you can live better and not be beasts of burden. No more beasts! Workers, my Jewish brothers, help me to fight for you! Don't let me fight alone! Stand with me in the battle against your bosses, against the little cockroaches! Donkeys, beasts, I am fighting for you! I am leading your battle!”

There was a hurrah in the hall, which mixed with spirited applause. The speaker spoke on, all in the same sentiment. Suddenly in a corner of the hall there was a commotion. The presider of the meeting, who was sitting behind the speaker, tried to calm the crowd down. Barondess called on him to sit down in his place, and he cried out, “Barondess needs no presider when he stands on the stage!…Quiet there! When Barondess speaks, it must be quiet!…A little courtesy, you boors!” And the hall filled with applause.

And as people remember, Yosef Barondess and his “donkeys” and “boors” built up the Jewish trade unions in America. It was fantastic, fascinating,

But the essence of that bizarre time stood not in the externals, in the twisted and grotesque, bug in the internals, in the deep, pure idealism that moved everyone and everything from its pioneering beginning. Leon Kobrin saturated his work with that. He brought it out by depicting the people from the masses, and by describing the figures of their leaders (Johann Most, Emma Goldman, M. Katz, Leon Moiseyev, Zametikin, Barondess, and others). And he shows it by describing his own

[Page 465]

first, uncertain steps, groping in darkness, in that crazy but excellent pioneering time.

In Kobrin's sharp descriptions of people in his “First Fifty Years” there are two moments that make a particular impression on the reader. The first image is the description of the creative urge that tormented him in his distant youth. Certainly it is difficult for a writer to examine his own writing laboratory. He thinks that he sees everything so plainly and clearly that he can see no other side, and he becomes ensnared in the internal tangles of his soul, which are often concealed from him, as they are for his attentive reader. For Kobrin it was completely different. He does not deal with the latent triumphs of his own spirit. He tells only, simply and openly, how the process developed in his creative years. And we so much enjoy his simplicity and openness that we believe his every word.

So he sits there, Kobrin, one early morning in 1892 in Philadelphia by a sewing machine in shirt factory and stamps a sleeve. He works mechanically, and before his eyes pass heimish pictures and heimish images. Each of them seizes him with nostalgia for his home, and the pictures, that he bears in his memory, are bound up with the most beautiful and happiest hours of his young student years. He sees in his imagination the fishermen who worked on his father's lake in the Mohilev District. He spent the last two summers before he left for America with them, and now they all, as if they were alive, swim before his eyes. They eat together. They spend time together, and they catch fish together. Here they pull the nets, and here is a sparkling fish caught in a net. His heart dances with happy excitement…and suddenly–a pain in his hand that extends to his shoulder. The needle of the sewing machine pierced his hand. Every morning he was free of being a sleeve-sewer in his whole life, but every morning he was shaping the embryo of his well-known novel about fishermen–“Yankel Boyle.”

Another time, however, life played a devilish trick on him, costing him both his job in a “shop” and his subject for a story.

He worked in a bakery, in a dark cellar, without windows, with damp, black walls, in heat and in stifling air, in

[Page 466]

dirt and filth, from eight in the evening until five or six in the morning. Three workers were there. The head baker–a short, fat little man, with a red beard and a face covered with flour; the “second hand”–a tall young man with a white cataract in his eye; and he, Kobrin, the assistant. He was already an anarchist and was seeking a subject for a story in Russian that would then be translated into Yiddish for the “Freier Arbeter Shtime.” During those long, flour-coated hours in the bakery, he decided to take his subject from the bakery and to make the head baker, with his family, the hero of the story. Naturally the hero had to be a former wage-slave, whom people had aggravated and made into a revolutionary. And so the young writer wove in his fantasy the forthcoming story. He described the head baker and laid out his whole life, as if on the palm of his hand, and then, he thought, he would have his hero cry out, “Enough! I'll spend no more nights in this stinking grave so that my boss can sleep peacefully in his soft bed.” Suddenly he heard a cry from his “hero”: “What are you doing there like a golem? Are you dreaming? Mix the dough! Move! Get out from there! Go to hell!” Things grew dark before his eyes and in his excitement he told the red Jew the whole story, including what he, the “hero,” was going to say in his revolutionary speech against the owner in the story. As the baker listened to what the young man said against the owner, he stared at him with flaming, murderous eyes: “Against the owner, R' Zissel, my landsman, you're speaking–a bloodsucker?” And he threw him into the chest of flour. Kobrin was no longer a baker, and his dream of the revolutionary tale was also demolished.

Finally–about Kobrin's understanding of his experiences in the those weeks and months when Paulina Segal, “the beautiful assistant of Emma Goldman,” came into his life. Love that radiates in poverty has been depicted by many writers before and after Kobrin. But love that hid and celebrated that poverty has not often been pictured. Kobrin described it with and tact and with moderation, simply and clearly and sincerely, without exaggeration and without artifice–it gives pleasure, cleanses the soul, and strengthens one's faith in people.

[Page 467]

On that night–Kobrin relates–when for the first time in his life he met Paulina Segal, he invited her for dinner to the best restaurant that was then to be found on East Broadway, and “he went on a spree”: it cost him six whole nickels…and the next day, when he came, as usual to the anarchists' office at 11 Pike Street, he no longer felt the hardness of the bench on which he slept, nor the difficulty or sadness that had bothered him the day before. Nor did he mind the messiness of the ugly people who surrounded him in the office. His soul was fine and light–says Kobrin–and we believe him with our whole heart.

And later, on their honeymoon, when they both lost their jobs (she in a coat factory, he at making cigars) and they had no more than five cents for bread, they had a story. A story about snow and sleet and a covering of bearskin, a story about love and a roll with herring and clearing the street of snow, but we will not tell that story; people should rather read it themselves to see the writer's fine mixture of dream and truth, of poetry and prose, of the gentle interior and the hard exterior.

A truly artistic and colorful work is Kobrin's “My Fifty Years in America.” It is a shame that there are no more descriptions from his later years, from the same pen.

In her forward to the book, Paulya Kobrin writes that she is fortunate to present the book as a gift to the Yiddish reader, and her husband and companion of fifty years–a last flower, a last, a last, but one of the finest and most fragrant flowers in the bouquet of Kobrin's works. The Yiddish reader will surely be grateful for this beautiful gift.

E. Golomb

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

In the fall of 1909, just after I graduated from the pedagogy program in Grodno, I arrived

In Vitebsk as a teacher in the local Talmud Torah. This was a reformed Talmud Torah. That is, it was not like the old, traditional Talmud Torahs from the old style but a modern school with a broader program of Jewish studies. Such reformed Talmud Torahs were at that time in the larger cities, where the directorship was put into the hands of modern people. In Vitebsk, the new directors of the Talmud Torah were a banker, Finkelshteyn, whom we seldom saw at the school; three doctors—Neifach, Lieberman, and the well-known Zionist leader Dr. Bruk. I think there were others. Among them were Mrs. Bernshteyn. Her husband was an optician on the corner of Mohilever Street and Smolensker Road, near Lutshesse. Of course, these directors chose to change the old teachers and bring in modern studies and modern teachers.

When I arrived late in the fall, all of these changes had already been made, but the school still was not operating because of a cholera epidemic in the city. Actually it was not very severe, and it did not affect the more intelligent and cautious sectors, but since November the schools had been closed.

The Talmud Torah had two departments. The upper department was in the center with several overfilled classes and several teachers. In the first section, near the train station, was a department with two classes and two teachers. In the third section was a small Talmud Torah with one teacher for two classes. (Because of poverty, this is how it was often done.)

[Page 469]

The program of the Talmud Torahs was the same as in almost all elementary schools: first, Russian, arithmetic, and a bit of Russian history. Jewish studies had a much looser program: Chumash, Tanach, together with prayers, and often Hebrew, even taught in Hebrew. This depended on the teacher's ideology. The directors seldom interfered in programmatic matters. Yiddish was seldom taught—and then it was illegal. In the community Jewish schools, the war between the Yiddishists and the Hebraists was already aflame. In the Talmud Torahs, the war was not so severe. In the general studies we should also number studies of science, which the reactionary government regarded with suspicion and as useless because the progressive teachers (like the intelligentsia in general) saw in the spread of scientific knowledge a path to liberating the people. This is not the place to discuss the connection between knowledge and liberation, although for people in the Americas it could perhaps be new and interesting. But this was a fact: the popularization of scientific knowledge helped greatly in bringing about the revolution.

People introduced prayer to the Talmud Torah only at the end of 1912, against the will of the teachers. And this was actually the reason that the teacher Nigdin and I left in protest.

Among the teachers, two older ones remained from earlier: Briskin, a Jew with a large family and not much money, taught Chumash and general Jewish studies; the second was Dande. He taught only general studies—a Russified Jew, a former governmental rabbi. Among the younger ones, outstanding was Zalman-Avigdor Chrapkov, or Chrapkovski. He supported a large family of brothers and sisters along with a widowed mother. They lived in a basement apartment. He was very capable. He was cheerful and happy, full of jokes and artistic ideas. Many years later, I heard, under the communists he had become a great and widely known activist.

Of the other teachers, I will recall only Dande, an older Russified person, who had his “pedagogical principles”: the whole new pedagogy, which dealt with “development-shmevelopment,” was not worth a cone of gunpowder. A teacher should enter the classroom with a ruler in his hand so that the students could see it with their very own eyes—so that the teacher could have good discipline. That

[Page 470]

was the goal. The most important subject in learning is handwriting. If you teach a child good handwriting, he can become a bookkeeper. And what can you do with your “development-shmevelopment” if your students cannot even sharpen a pencil correctly? A good child always has his pencil sharpened evenly, with a sharpener—If you want to write a judgment, write with the edge. Understand?...

He taught me Torah very often and was proud of it. We encountered each other frequently in the small division, where he taught general studies as well as Jewish subjects. He had “good” discipline—the children trembled before him, and kept their heads down. Was he not correct about his pedagogy?

There was nothing outstanding about the other teachers—it was a time of general reaction. More interesting were some members of the directorate whom I knew. These were Mrs. Bernshteyn and Drs. Lieberman and Bruk. Mrs. Bernshteyn lived near the small division, where I taught two classes simultaneously and had terrible problems with discipline. Almost every day she would come to console me, to cheer me up, so that I should not take the problems to heart: never mind—others have it worse…She was generally cheerful, laughing. Often I would find on my table a book. The attendant would tell me: Mrs. Bernshteyn left it for you. Even today I am grateful—she made my difficult experiences easier in the first year of my teaching.

Dr. Lieberman was a man of rare religiosity. He would pray three times a day. On Shabbos he would visit the ill, which three rabbis gave him permission to do. On Shabbos he would go around with a non-Jew to whom he would dictate prescriptions. When he was in our neighborhood, he would come into my class, sit for a while, and have a friendly conversation, speaking Hebrew and assuring me that I was complaining for no reason: he saw that I really wanted to be a good teacher…

A man on even a higher level was Dr. “Zvi ben Yakov Bruk.” This was the name on the little plaque on his door. But we used to call him, in the Russian manner, Grigory Yakovlevitsh. At that time he had no family. For a long time,

[Page 471]

his mother had lived with him. She would beg him, “Hirsch, go eat”—not Grigory and not Zvi. He was one of the first Zionist activists in Russia, a constant attendee at Zionist congresses, a deputy in the first Russian duma (parliament). Along with all the other radical deputies who in Vyborg signed the proclamation to the population after the government had dissolved the duma, Dr Bruk did not dare to take part in the country's political life. Dr. Bruk only participated in community activities. He was especially involved in the literary community. This was a legal activity that had open lectures and meetings at the merchant's club. There were meetings almost every week. Bruk was the permanent presider. He was dynamic, impulsive, good-natured, funny, a master at discussions. Especially he got off badly with people who ruffled his ideology. I remember that once a Jew came, a writer in Russian, Okuniev, who wanted to flatter the community, He spoke sympathetically about those who “don't chase after gold coins,” who live together with their suffering people, and so on…I remember how Bruk gave him a piece of his mind: “We don't need Jews who come to compliment us.” He said it with such fire and heat! I remember that he had to read a lecture about Bialik. He asked me to come with him in the evening lest he forget a Hebrew word as he was preparing. I arrived before him. His large apartment was in turmoil: in one room there was a committee meeting, in a second room a play was being rehearsed, here people were having a discussion…Who had such a free and comfortable apartment as Dr. Bruk? When he finally came from his rounds, he barely asked to be left alone for an hour in his study.

He was skillful at sitting around with friends over a glass of coffee and telling jokes and Yiddish stories. One such story about the “Gelvaner (Gelvan—a little shtetl in Lithuania) with pointy heads and keen minds who wanted to create a “Fellowship of Watchmen for the Morning” I remember to this day. But for such lighthearted moments he had little time. We, a group of young men, would often come to him: we wanted coffee. He would excuse himself: he was too tired out, he had to rest. Take a fiver and go yourselves. “You don't need me, but I will pay. Take a fiver and go yourselves, in good health”…

[Page 472]

After working at school, I would often meet him as he rode in a droshky or a sled. He would always stop for a chat.

“Where are you headed, Doctor?”

“Where should I go? I go to their homes is where I go. But sit near me. We'll travel and talk. I'm lonesome.”

“Go on. You're tired out. I'll eat—” I would invite him, but it did not help.

“That's news, that I'm tired. I dare not eat when I'm tired, but if you'll go with me, you can rest before you eat.”

How could one refuse? On the way he was seldom in a good mood: “Such poverty! Such poverty! Since the rich don't call me, only the poor…When I come to a sick person, I don't know what to do first, to write out a cure or leave a ruble for bread or wood.”

And he often left both things for his patient, the prescription and the bread. On one cold, winter day I saw him traveling without his winter fur hat.

“Doctor, where's your hat? It's cold,” I said to him.

“I have such luck with poor people. Nu, early in the morning I've already been to a sick poor person who had nothing at all in his home. What could I do? I gave them my hat so they could pawn it. I'll go later and redeem it. What could I do?”

One time, traveling in his sled, he spoke in this way to his driver and told him where he was going, without getting a response. “It's always like this,” said Bruk, The Gentile drivers, when they drive me, are silent. They know that I give Jews an extra ruble.”

As we arrived, he paid the driver, who said, in Yiddish, “Thank, Doctor.”

“Ah, you actually are a Jew. So why so silent? I thought you were a Gentile.”

“Don't think about it, Doctor. I'm a little deaf…”

“Well here's another ruble. Go in good health.”

People in the city told stories about him, how he rescued a child who was suffocating from diphtheria by sucking out the mucus, and so on.

[Page 473]

One Friday evening I came to him about something. He was lying on a sofa, hardly breathing, gasping.

“What's wrong, Doctor?”

“God finally sent me a rich patient and she turns out to be an idiot. I wrote her a prescription for iodine and she took the prescription and drank it all down at one go. I barely saved her. Who has the strength for this?”

“Nu, I'll come back another time. Rest.”

“No! I haven't seen a newspaper today. There's a new “Rezviet.” Read it to me.”

In Vitebsk there was a Yiddish theater. This was in the fall. Lipovski's troupe had played in a summer theater. Outside it was already pretty cold. But Bruk would go every evening to be in the theater, and not alone—our whole group of young men went at the expense of the wealthy man. He really was not wealthy, but he loved the fellowship.

His waiting room was interesting. He cured me. I had developed a nervous stomach from my discipline problems. Not wanting to take advantage of Bruk, who would surely not take money from me, I went to another doctor (Sheinis or Sheinin—I don't remember). As a treatment he told me I should have a cook and a nurse, and I should not work…As if! I sought advice from the best of my fellow teachers, from Chrapkovski. He persuaded me to go only to Bruk. I came for the first time to his waiting room, a room full of Jews who groaned and moaned from their woes. Near me on a round table lay a parchment with “A Song of Praise, to Zvi ben Yakov” in the style of a chapter of Psalms written by the well-known Hebrew writer Mordechai ben Hillel HaCohen when Dr. Bruk had left Gomel to come to Vitebsk.

There was no nurse there to receive the ill. The ailing themselves went in order. From his “cabinet” (in Russia, a doctor did not dare to have a sign or an office, only a “cabinet”) one could often hear how the doctor yelled at a patient, “Don't groan. I'm sicker than you are…” or “I've told you should say 'yes,' not 'oy.'”

He opened the door to the waiting room and saw me: “You, too? Just wait. I'll take you after everyone else.

[Page 474]

After a little wait, I entered his “cabinet.” He asked me to let him rest a bit, while we had a conversation: “How's your work? What do you have to say about this or that article?”

Only then did he consider me and say, “You were at Sheinin's? Did he say thus and so (as if he had been there)? A real wise man. You can't do what he said. Do you know what? I will heal you “in a woman's way.” Instead of compresses, wrap a towel around you…and so on…If that doesn't help you, I'll cure you in a medicinal way…”

Jews once had such doctors. In Tel Aviv there is, by the way, a side street that bears the name of Dr. Bruk.

In the work of directing the Talmud Torah, he seldom mixed in.

There were no great accomplishments in the pedagogical work in the Talmud Torah. But there were even fewer in the elementary school for Jewish children, although one of the best teachers was there, Yakov Gershteyn, who later was one of the pillars of the Jewish educational system in Vilna. The bureaucratic lackadaisical spirit brought no fresh winds, no modern pedagogical thought. In a sense, the Talmud Torah was much freer and more advanced: lackadaisical routine did not rule there, and the teachers had more freedom. The children were even allowed on a free Shabbos to come to their teacher and he would read to them a story by Sholem Aleichem! Not all the members of the directorship knew about such heresies. Perhaps not all the teachers did either—and certainly not the chief director.

How hard was the reaction to such small matters: the newspapers brought the news that Tolstoy had died in a dramatic way: an old man running away from home, he died in a small railway station. I decided in class, where I taught Russian, to tell my students about him and to read them one of Tolstoy's children's stories. But first, in the morning, an inspector was there. He wanted to observe an arithmetic lesson, so Russian would come later. After the lesson, we had a friendly talk, and I told him that in the next lesson I would present Tolstoy's death. He said to me:

[Page 475]

“There's no rule against that, but you are still young. Why should you being like this. Better to omit that…”

He wanted to keep me from making a mistake. This was at the time of the awful reactionary environment.

The elementary school was a state school. It was supported by funds raised by the tax on kosher meat. All of the teachers were “institutionalists,” which means that they were all former students from the “Government Jewish Teacher Institution” in Vilna. That institution was supported by the government (with special Jewish funds) from 1873 until the evacuation of Vilna in 1915. The aim was to prepare teachers to Russify. In order to separate them completely from Jewish life, they were kept for five years in a closed dormitory. Of Jewish studies, they were given a little of the “ancient Jewish language” (Hebrew), but of course they were taught the “ancient language” in Russian, and they also learned a little of the “Bible.” Most of the graduates emerged, naturally, as bureaucratic Russifiers, although there were also a small number of exceptions. One such was the aforementioned Yakov Gershteyn. Some years later in the archive of the Teachers Institute, which was absorbed into the Vilna YIVO, I found a record of one of his transgressions: while he was in the Institute, he liked to bring together friends to sing “songs in jargon [Yiddish]”. But in the elementary school in Vitebsk he could not show his love for Yiddish. But when he came to the Literary Society, he felt far differently: he was tall, healthy, with a loud, clear voice, always happy, always good-natured…Later on I came to Vilna to work with him in the Teachers Seminar the whole time that I worked there. I never remember him being in a bad mood, unless someone from the large Seminar chorus, which Gershteyn led, sang a wrong note. In 1907 Yakov Gershteyn was arrested for taking part in the illegal teachers' meeting in Vilna. The teachers' conference continued its work in prison and there developed a resolution about a Jewish school in Yiddish. Yakov Gershteyn belonged to that order of men who did not know how to change. He died in the Vilna Ghetto in the same house where he was born and in which his mother was also born and died. Throughout his life, he never changed his ideas, and he always

[Page 476]

presented them with his smile, with his high, silver laugh that could make walls tremble. But in the Vitebsk elementary school, he could never show his attachment to Yiddish.

An opposite kind of person as the leader of the three-class Jewish folk school, Yunavitsch. His school—a cheerless building, with large inscriptions on the walls, verses from Chumash or from Tanach, all in Russian. He would speak only Russian, with true Russian expression, in the Muscovite style. He hated Yiddish the way a religious Jew hates pork. I remember that once he had invited us for a glass of tea: he had hears that we young teachers were hanging around with the Literary Society and that we often spoke Yiddish among ourselves… ”I can't understand that,” he said to us. An old-fashioned, marinated assimilator.

And this was not only in the time of the great dark reaction. At the same time, in the “underground” of Russian life, the coming revolution was being prepared.

In 1910, there were summer courses in Vitebsk for teachers, led by professors from Petersburg whom the Minister of Folk Education had chosen from the universities. How much courageous zest these couple hundred Russian teachers had and how much love for the people, for the simple peasant and for his soul, showed the beautiful, deep Russian intelligence. I remember even now, our intimate private conversations (there was barely a minyan of Jewish teachers) with a Professor Dushetshkin (literature), Moltshevski (chemistry), or Liovshin (history), and others. How much loyalty and love for the simple people they had! The worst impression was made on everyone by the apostate Shochor-Trotsky (mathematics). He had such fine phrases for one and all, and how deeply everyone hated him. There were a lot of Jewish apostates there…they are not worth remembering. At these same summer courses, I became friendly with a couple of teachers from the women's gymnasium at Aleksandra Varvorina. We often got together, especially in the laboratory of the physics teacher Vladimirov, from whom we learned so much. They were typical of Russian folk intellectuals—faithful, generous, regarding their work as a duty to. “sanctify the people.” Perhaps they sowed in us young Jewish teachers the seeds of faithfulness to our people and to their peoplehood.

[Page 477]

Forty-three years later we are a bit older, experienced in where the world is headed, having worked in all the countries where Jews live, but we cannot forget those first three years in Vitebsk—my first three years of teaching. Almost fifty years later I recall the streets of the city, I remember people, events, a great deal of hardship and also a little teacherly success. I remember our walks on the boat on the little Vitba River. I remember how we ran for tickets to see the first time a man flew in an airplane.

When I was young, starting as a Yiddishist, a true Yiddish school system was just a dream. Wherever and whoever took the first steps, hesitant first steps, then stronger, raging controversies over the language…

We saw such broad horizons for the future…Now…we look back—a sea of blood, killing, and destruction. Lives and dreams—all killed, and in a cold world from a cold Yiddishkeit one writes Yizkor Books.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vitsyebsk, Belarus

Vitsyebsk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 06 Apr 2025 by JH