|

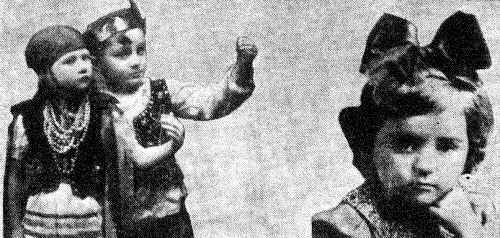

From right: Rachel Motzni, Yisroel Inselbuch and Tzivia Tunick

|

|

[Page 316]

In the Ghetto and in the Concentration Camp

by Getzel Reiser

Translated by Melissa Rubin McCurdie and David Rubin

Destruction

On Friday 27th June 1941 at 2 p.m. in Stolpce, after a difficult battle with the Soviets, the Germans occupied Stolpce. The shooting started at 8 in the morning and by 12 midday the town was already in flames.

The German tanks drove through the streets and the houses on both sides were burning. A few Jews stood and poured water on the cellars where their few possessions were hidden - they still thought that they would still need them. At dusk when the flames died down a little, it was noticeable in Yurzdike and Shpitalne Streets that a few houses had remained. When it got darker each one started to look for a corner where they could spend the night. At that time there was no particular fear of the Germans because, as it turned out, the tanks had moved on.

|

|

| Innocent Children From right: Rachel Motzni, Yisroel Inselbuch and Tzivia Tunick |

Early on Sunday morning, the Germans started taking us to work in small groups. Many had already tasted (experienced) their terrible beatings. Coming back from work we already heard the “good” news from Shpitalne Street, where they had taken out 72 men, stood them against the wall and shot them, before the eyes of their wives and children. They threw grenades into some of the houses and burned them together with the occupants. The number of corpses from that Black Sunday reached more than 200.

A few of the corpses from that Black Sunday were only found 6 months later when the Germans ordered the clean up of all the places of the burnt houses and they found human limbs, faces and rotten hands in the bottom of an oven[1]. The Chevra Kedisha gathered it all and brought it to the cemetery for burial.

A few days later, the Germans ordered the establishment of a Judenrat[2]. The first notice to the Judenrat was to establish forced labour. Men between the ages of 15-60 and women between the ages of 17-55 were forced to work.

Every day, quite early, 1400 Jews used to go out to the umshlagplatz[3] and from there to work. Each one had a number on a small square piece of cardboard. This indicated to which group of 100 this person belonged and this is how they arranged themselves, every morning, according to the numbers. Each one at his place.

The sonder-commando used to come and select skilled workers separately and hard labourers separately. They were divided into groups[4] according to the needs of each work place and these groups were sent to work under the supervision of German or Christian officials. Before they divided us into groups they used to count us every day. In this way we went to work every day but coming back from work as an entire group, was a big miracle. Many times, on our return, our group got smaller.

One day returning from work, they surrounded us on all sides and snatched 87 men from us (of free professions and other notable persons), who were pointed out by young non-Jews who were sitting with a German Gestapo man in a vehicle.

In the Ghetto it was said that they had been sent somewhere to work. Later women said

[Page 317]

that a Christian man brought regards from them that they are working in a soap factory near Orshe and they are asking that we send them food.

|

|

| Untitled Photograph of German soldiers standing among corpses |

At that time no one knew exactly what happened to them. Only when the rains started, some people came across a pit in Akintzitze Forest by chance. Only through the clothing did they recognize Chaim Dvoretzky, Moshe Bogin, the Rav Shleime Chari, Leizer Leib Shleif[5] and the others who were shot there together.

A second misfortune happened on Friday before Rosh Hashanna 5702. Suddenly at 10a.m. we were informed at all work places that everyone must immediately go to the umshlagplatz. Everyone came and arranged themselves into their respective group of a hundred. The sonder-commander came with 20 Germans with loaded guns.

He started calling the numbers of those who should come out of the rows. He chose approximately 18 people and added another two who were sitting in prison. These 20 people were taken and shot at the cemetery where our workers prepared graves for them.

Heart-rendering scenes played themselves out when these 20 people were marched past their homes and took leave of their parents, their brothers, their sisters, their friends and their neighbours. A similar scene played out in Yurzdikke Street where Rachel Bruchansky walked past. She was Yehoshua the wagon owner's daughter, an 18 year old capable and beautiful girl.

Among the 20 people were people from Stolpce: Shleime Harkavy's daughter and her husband, the abovementioned Rachel Bruchansky, Benjamin Bruchansky (Michal's), Noach Berenshtein, Mottle the son of Odess Masha Tov, Dovid Matte Reiness, Avrom Tribuch, Yehoshua Inzelbuch (Beryl Shoshe's son) and many of the refugees (escapees) who came into Stolpce. Harkavey's son-in-law, Yitzchak Weinrib worked in the command and was well acquainted with some of the main murderers, so he asked for mercy for his wife. When this did not help, he stood by his wife, of his own free will, and perished leaving a two-year-old orphan.

Zissel Rudztisky, Eli (Eliya), Yossel Ber's son, Shaul Meckler his brother-in-law and Beryle Tunik, Sholem, Yashke the butcher's son - this group was sent by the commander to a field to dig up potatoes for the command (the German command). Each one of them was longing to bring a few potatoes home to still their hunger.

The German noticed this. He informed their guard in their command and the murderer Reichel came down and he ordered them to be arrested. In a flash this information came to the Judenrat and at the same time to Nechama Tunik, Beryl's sister who worked at the German air force base. Because of her request a high-ranking officer of the commander came immediately, asking for them to be set free. They ordered him to run to the place where they took them to be shot but he came to the grave five minutes too late.

The Judenrat also tried to intervene on behalf of these three with the command and because of that, they arrested the whole Judenrat for 24 hours. The Press's son Witenberg, Witze Press's Yirmiahu Prass, the members Zeev Tunik, Tanchum Shulkin, Alter Yosselevich, Yehoshua Weinreich, Beryl Moshe Reisser, and Leibe Kumock.

In 24 hours they were chased three times from one cellar to another. In the corridor stood two rows of thugs and they beat them murderously with rubber truncheons. One tried to intervene with the Mayor Vanye Avdjez and he said faithfully that according to the information he received from the commander, he guaranteed that within 24 hours they would be released. The next morning they indeed freed them.

Coming back from there beaten and sick, they had to return to their work early. It had to remain a secret that they had been tortured.

Herschel Radunski, the grandson of Schmerel the Shames, worked at the air force base. He did something wrong. The murderers ordered him to dig a grave for himself next to the window. Through a miracle he then saved himself.

At this time we got to know from Swierzne that the murderers selected 30 people including the Rabbi and shot them (with the accusation of sabotage). In the meantime, tragic messages came from Turetz that there had been a massacre there. They had sent a few of them to work in the mill in Swierzne.

Before Pesach we found out that on Shoshan Purim[6] in

[Page 318]

Baranovich, there was a massacre - 4,000 Jews of the 12,000 Baranovich residents had been shot.

Among us various versions circulated, they said that we will also not be spared. A large number of ignorant and helpless Jews consoled themselves. Others used to tell of what they heard from the Germans at their places of work, that such things could not happen in Stolpce, because here almost everyone goes to work. And there is a lot of work. We are useful Jews and we have earned enough to survive the war.

In the meantime one needs to get ready for Pesach. The community baked Matzos at Shoshe Aginsky's house. At her house was an oven to bake matzos[7] from year to year. Near her house they put up a gate to the Ghetto. They began to talk about locking the Ghetto.

The boundaries of the Ghetto, it was determined, would extend from the yellow church, along the length of Yurzdikke Street and on the right side which was Potshtoveh Street[8]. The entire length of Potshtoveh Street was cordoned off with barbed wire along the pavement on the right side, and the middle of the road was left free for traffic, but unfortunately not for us Jews. We owned the small sandy street at the beginning of Yurzdike Street until after Yakov Leib's blacksmith shop.

In the meantime, we were confused, all the while preparing sheds to live in. Some others put up barricades.

Dr. Yechiskel Sirkin and the family of Velvel, the ferryman, occupied Yakov Leib's old blacksmiths shop as their home.

Velvel and his son Reuven were already dead after an attack by Latvians. Alter, the teacher, built a new barrack next to the blacksmith's shop. In this way, everyone was occupied keeping watch over the tradesmen and improving the ovens themselves and the plates on the ovens. Each one was planning to make a bunker, a little hiding place under the oven, or just a generally concealed cellar – each for his own family, in case of need, heaven forbid, one should have a place to hide oneself.

Even though life in the Ghetto was materially very difficult, you would see in the evenings, young couples going for a walk. Saturdays, some of them went to pray. Sundays, they didn't work for the Germans, but of their own free will, they worked to make the Ghetto more habitable for them. With the permission of the authorities, the Judenrat built a two-story house in the Ghetto. Another house was built from the remaining old bricks from the burned out houses in the form of a long trench that had, in the middle, a corridor with many small rooms.

In each little room, there was a family with a separate oven on which to cook. The women used to argue in the common corridor. The children would fight with one another and the parents were also drawn into the conflict.

The urge to want to live was very strong. We didn't hear of any instances of suicide. The enslavement was great. The cold detachment and calculated lack of communication of the Germans prevented us from thinking of evil, because each one used to think that it couldn't get worse than the present and perhaps at the price of need and pain, they would save their lives. In addition, they received words of comfort from the Shtetl Rabbi, Rav Yehoshua Lieberman “Of Blessed Righteous Memory”[9] Being enslaved to their work, and bound to their families, no one wanted to think about anything bad. Some knew that there were a handful of youth that were occupied with various secret plans. They were even preparing weapons in secret for an uprising or preparing to escape to the forest. At that time, one had hardly ever heard of Partisans. Perhaps a few people did know something about them.

Suddenly, the 26th August 1942 arrived. At 2p.m. we were informed “as quick as lightning”, at all workplaces, through the Judenrat, that everyone must come to the Ghetto immediately. It became chaotic as each one ran to ask the Judenrat. They themselves were also shocked. It didn't take long and everyone was standing in four rows. The sonder-commander gave a half an hour to collect some possessions - we were travelling for work for not longer than 6 weeks. They counted out 500 men who had to march to the train station immediately. We were divided into two groups – 270 men to Baranowicz and 230 to Minsk. We arrived in Baranowicz late at night. We slept the night at the station in Falesk in the room where the canteen once was.

Early the next morning, a German in Gestapo uniform arrived. He chose 30 tradesmen: cabinetmakers, builders and carpenters. He took us to Potshtoveh Street in the service of the SD where we were arranged and sorted again, they left 9 men in that service and the remaining 21 men were sent to Kolditzeve.

A new chapter begins for the Stolpce people in Baranowicz. We are still naïve and remain waiting until breakfast. Then we will receive an order, where (to go) and what to do.

In the meantime, at breakfast, we meet up with Jews from Baranowicz, Lechevicz, Meitshet and Horredicz.

We heard from them that they had a similar experience to us. At first they took the men, and then shot the women, children and old people. We understood that this was not a good sign. It's

[Page 319]

hard to believe and as we are still here as guests and strangers, we don't think about anything.

The first day after work, they took our 9 men to the Baranowicz Ghetto. The Judenrat, whose head was Mulye Yankelevicz, established a place for us to sleep, in the quartermaster's office opposite the Jewish Council right at the gate at Sadoveh Street. From here we went together with the Baranowicz Jews, four in a row, to and from work, guarded by a Gestapo patrol.

In the meantime, we came to know the details of the first massacre that took place on Shushan Purim in Baranowicz.

On the third day after our arrival in Baranowicz, on 29 August 1942, the work details were encircled as they marched out to work and about 700 men were sent away to Molodetsneh. At the action, heart-rending scenes are played out. One girl was shot in the middle of the street for wanting to step out of her row. After working for a few weeks, we were longing to meet with our 240 Stolpce brothers, who worked in Aleph Tet. (Organization of Tet Aleph Dalled Camp) at the Falesk station.

In return for our skilled tradesmen's work we received permission from our superior to go and meet them. He gives us the final instructions: arrange ourselves in threes in three rows and march close to the pavement. We came, saw everyone and marched back in the best order without any patrol. In Alef Tet camp, we met another group of 80 men that were brought from Stolpce on the 11 Sept 1942, Erev Rosh Hashana 5703.

In the meantime, we find out about a current resistance initiative that was organizing itself in the Baranowicz Ghetto. The work details that were returning from their work, were smuggling in weapons. More than once, these groups were thoroughly searched when they returned from work to the Ghetto. The Judenrat decided to build a bakery on Arle Street in an unfinished large house.

To this end, the Judenrat turned to the superior of the SD to select 2 specialists to complete the building of the bakery. The purpose of building the bakery was: firstly, under the oven, they prepared a big bunker for machine guns; secondly, by bringing flour into the Ghetto instead of ready-baked bread, it would be easier to smuggle more weapons into the Ghetto.

All these plans were disrupted on the 22 September 1942, the day of the second massacre in Baranowicz, which took place exactly on the morning after Yom Kippur. The bloodbath lasted for a week and two days later, we heard that on the 12th Tishrei 5703, corresponding to 23 Sept 1942, the first massacre took place in Stolpce where we lost our dearest and best[10].

On the first day of Succoth, they made the Baranowicz Ghetto smaller. After the working day, they brought the remaining Jews back into the Ghetto on Potshtoveh Street. The next day, which was Sunday, we didn't go to work. The weather was beautiful, and the will to live among the survivors became stronger even in the worst moments.

From the chimneys in the Ghetto, smoke is rising again. Women are peeling potatoes, baking latkes, the young people are walking in the street, and the mood was a little better. Early the next morning, everybody was again standing next to the gate in their rows. It was noticeable how many of these work details had become depleted.

The important work details together with the SD, marched to work. The remnants of the people huddled together, one to the other. They were trying to smuggle themselves into the departing rows but were unsuccessful, as they were beaten back under a hail of rubber truncheons and sticks.

At that moment, a man came from the field commission and asked all the remaining inmates to arrange themselves in fours. A sense of urgency arose and everybody was pushing themselves to be first. Seventy percent were women, and the man from the field commission added 300 men and they went out through the gate.

Immediately, began the murder of the elderly and children. Approximately 600 people were murdered, amongst them, elderly men, women and children. When we returned to the Ghetto at nightfall, it again became very quiet as if nothing ever happened. It didn't take long and the chief executioner, whose name was Amelung, may his name be erased, was preparing his plans to travel home on leave at the end of December, so he wanted to finish off the Baranowicz Ghetto.

On 17 December[11] quite early, a disturbance began again in the Ghetto. Some were already running to the barbed wires. The Ghetto was surrounded by police and the first gunshots were heard, and the first victims were already lying on the ground. The work details at the gate were being sorted. The more skilled workers were left behind and were transported to the workshops and Baranowicz now remained Jew-free.

Next day, we read about it on the placards all over the town. In fact, there remained in the Baranowicz environs another 800 Jews but they remained confined at their work places day and night. Approximately 200 Jews, most of whom had free professions, were sent into hell of Kaf Tzadik at Kolditzeve. This was a good 17 km from Baranowicz and there they found 21 people from Stolpce. Later, they brought another few skilled workers from Stolpce to that place. There the Jews were undertaking a hunger strike. Every week, a Minyan[12] of Jews would die there.

[Page 320]

The Colony S.D. numbered 113 Jews. They put them in the house of the newly evicted baroness on Potshtoveh Street across from the workstation so it would be easier to guard. There we stayed for 10 months.

In the meantime we received information that the group of 250 Jews, in the direction of Fledboi, was already liquidated.

The oldest among us, Goldberg of Blessed memory, prepared a plan of escape for us. He was in contact with Christians from the town and with Partisans and almost every day he would travel into town. He had many opportunities to escape into the forest but he wanted to lead us all out together. Frequently he claimed that the way is secure. He had even organized four non-Jewish guides, which would cost half a million Roubles.

He used to say that he had money for this purpose. But we needed to stay united. In the meantime we got to know that amongst us are two friends of whom we needed to be wary. The Germans found a doubt in their Jewish ancestry and any day they could be freed. We started to hide our activities from them. On the other side, a young group was established who collected guns, which engaged in various complicated exercises but they were capable of gathering some weapons.

They did not want to take in any new partners and held secret meetings. At any moment they were prepared to escape. Goldberg tried to come to an arrangement with them but they denied it completely. Everything was useless.

In the last days of October 1943 we received information that the last few Jews from Aleph Tet are being taken to Kolditzeve. There they found 240 people from Stolpce and a few from Baranowicz. In the vehicles in which they transported the Jews to Kolditzeve, they transported tar for heating on their return journey. To unload the tar they took our workers, who told exactly that they found photographs in the vehicles of families from Stolpce.

For this purpose they set up ovens in Kolditzeve heated with straw and they chased the Jews into the ovens and burnt them.

Hearing this shocking news, we became frantic, what does one do?

Goldberg called a meeting of 7 people to decide what to do. We decided that on the coming Sunday 17 November at nightfall we had to escape. Each evening when he returned from the town he used to give us a report that everything is in the best order. He already had four guides. The fifth guide would have to be appointed by a comrade from amongst the youth. On Tuesday the comrade travelled to town and returned satisfied. Everything is in order. In the meantime at noontime young comrades discussed with us that we cannot wait until Sunday because it will be too late. It would have to happen immediately on 3 November and we cannot wait until everyone returned from work. The first ones left as soon as it started to get dark in the evening.

It became noisy, a lot of chatter: Noah went, Zalman, Hillel, Feleh, Soveh, Chana, Zaturnsky and his wife and a 6 year-old child.

Our messenger ran to inform them at the workstation and from there a few also escaped. It became disorderly there and people stopped working. A German came in and he was shocked. A strong guard of White Russian police encircled the workstation and our house across the street. Those who were brought from the workstation were badly beaten. Immediately there arrived a chief thug with his retinue and he issued an order that we should arrange ourselves in two rows and he shouted: “You want to run to the Partisans, you yourselves want to become Partisans. Such swine.”

He counted us, 77 remained and 36 had escaped. His order was to send everybody to Kolditzeve the next morning.

After he left it became chaotic and a cry broke out, we all already knew what Kolditzeve was. “It is better to die here than to live in Kolditzeve.”

The guard outside told us sternly; “Go to sleep.” We remained in the beds and we spoke quietly. Some said they are sending us there to get rid of us. Others again said that there would be a selection. Nevertheless the night was a sleepless one and one of farewells.

In the morning quite early everyone was already dressed and waiting not knowing for what. A few looked through the windows in fear to see if the vehicles are coming to transport us to the pits in Baranowicz. Around 8 in the morning, one of the thugs came to us quite calmly. He ordered that all the skilled workers go to the workstation to pack up tools to prepare themselves because in the afternoon we are going to Kolditzeve. The unskilled men would remain in the house – another shock.

The last ones were afraid that they would be regarded as useless and that they would shoot them all.

Some wanted to commit suicide. The only thing that they could think of was to go up

[Page 321]

to the attic and hang themselves. I thought to myself would I be able to allow such a death? No. I controlled myself and I felt that I would not be able to carry out such an act. I became hopeful again as usual that if my fate is to die then I want to experience the taste together with my dearest and best.

In the meantime there came news from the workstations that Simcha the carpenter cut his throat with a knife – he already knew the taste of Kolditzeve. For 45 minutes he suffered and it was shocking to see until they appealed to the head hangman that he should shoot him in order to alleviate his pain.

In the afternoon they packed us into three trucks, counted us and we left. An hour later we were already in Kolditzeve. They pushed us through a gate guarded by White Russian police. The place was fenced off with barbed wire. There we met up with 130 heavily guarded emaciated Jews, depressed, torn apart and hungry. With joy they ran out to welcome us. They were living in a horse stable.

Approximately an hour later at 6 in the evening we heard a loud whistle calling everybody to line up on the parade ground in three straight rows and they counted us - there were over 200 men. All this had to happen at a fast pace. For the smallest wrongdoing one would be hit on the head with a rubber truncheon. We heard an order: “Run to the kettles and go in rows to the kitchen.” Next to the kitchen there stood before us 500 arrested Christians and then it was our row. At a distance there stood a commandant who took care of the arrangements.

When it was our row's turn to receive the little bit of watery radish with beetroot, rubber truncheons were raining down on our heads.

As we were returning from the kitchens they counted us again and in this way they continued to count us six times a day. After the last count they locked us in a barrack for the whole night.

The people pushed together on the bunks. There was still not enough place. Some of us snuggled up between acquaintances on a bunk and the remainder laid themselves out on the cold earth. The people of Kolditzeve said that our coming here did not augur well for us. The mood was a depressed one. The camp looked like a railway station. You had to be dressed at all times, prepared for all kinds of trouble, stand here and run there. The night was a difficult one and you could choke from the air.

We barely survived to see the next day. As soon as the door opened everybody ran out to catch their breath. They were already ringing and everybody is standing in formation.

4 November 1943

They count us in case someone remained lying fainted in the barrack - it is no excuse for them because a Jew does not have the right to die a natural death.

After the counting we go to the kitchen for breakfast – a little water with a paste made of flour to thicken the soup. We swallowed it quickly, again parading again counted and they swore at us insulting our mothers a few times. The commandant announced: All skilled building workers to their work. The remaining ones were chased back into the barracks. We were taken to a big building. Here they were building a huge prison. We are set to work. We would have been satisfied working hard with bricks and mortar and eating absolutely nothing as long as we were allowed to live. But this didn't last long.

At 10 a.m. a policeman arrived. He ordered us to stop working and to arrange ourselves in the rows. He leads us back to the camp. As we came nearer we saw all the Jews standing arranged on the parade ground shocked and confused. We joined their rows. A commandant runs up and says: Whoever has money and watches should give them up immediately. And if we find them on anyone he will be shot immediately. Those who were standing there before us had already surrendered everything. From a distance we see a group of murderers with rubber truncheons and sticks in their hands, approaching us. Our feet are breaking from fear. A moment later rubber truncheons are raining down on our heads. They begin collecting useful ones and tell them to arrange themselves in 3's - one behind the other.

A hundred meters in front of us they put together the un-needed ones in a group. There came an order, nobody wanted to be the first. A hail of rubber truncheons and sticks hit them on their heads until the young Rabbi from Slonim put himself in the front and our Leib Ahre Gruness (Shaye Gruness' son) placed himself in the second position in the first three. The cry is huge. The heart is petrified and everything became dark before our eyes.

We stood like this in the cold field in a cutting wind, frozen and shivering.

Our lives became terrible. We hear a cry to those who were chosen to die - “March.” They go proudly. They are fulfilling the mitzvah of sanctifying the Holy Name.

When their figures disappeared on the other side of the gates they told us to take the kettles and go to lunch. On our way the chief says “We have now finished with the Jews. You 100 men are no longer Jews. You will beat off the mark of shame that you carry. You will put a badge on like all the other obstinate ones, a white stripe 15cm x 5cm on your right breast”

[Page 322]

back to back with the same stripe at the back. We expect honest work.”

In the meantime a few tailors go to the chief to try to save the tailor Leibovitch, showing that without him, it would be difficult to manage the workshops. The chief, not thinking long, climbs into the vehicle and brings back Leibovitch. He climbs out of the transport half-dead and shaken. He was already naked, lying with his face in the ground in the third group of six waiting to be shot, when the chief went to bring him shouting out Leibovitch! Leibovitch got up and ran to him shocked and the chief told him to get dressed and he ran to the heap of clothes but didn't find his own things. He grabbed short small clothes and boots. When he returned to the barracks, he fell in a faint. They tried to revive him and put cold compresses on him and he came to six hours later.

The same also happened to the young boy Gorelik. Lusia, Yisrael Moshe Mowsowich's daughter from Swierznie, worked for the chief and pleaded for her cousin Gorelik, whom the police found cutting boots with a knife. He was severely tortured and he lay unconscious for 48 hours.

These two incidents showed us exactly what “reviving the dead” really means.

Here begins our new and final chapter in Kolditzeve. Instead of our clean beds in Baranowicz, here we had a wooden bunk with a pile of straw and a camp of lice, fleas and mice. We ate the meat of dead horses. We endured a few lonely terrible days and everything struck us anew.

Once, returning from work, we started discussing an escape to the forest as a group. We started making plans of how and to where (we would escape).

At the end of December, it was decided that we would wait until the coming of the dark nights and then we would quietly cut a hole in the wall under the wooden bunk that leads into the tannery. From there, opening the door that leads onto the barbed wire, a stretch of five metres. We would cut the wires and go across the mud. In the planning it looked fine and good but in reality, what kind of difficulties! People gave different opinions. What? To go to a certain death, then its better to wait here – was also a consideration. However, after a long and difficult discussion, it remained agreed upon by everyone that we must escape.

In the case of us being caught, we should prepare little bottles of poison. Barre Neifeld took the responsibility of preparing the poison. There was a panic where to find little bottles. They were also producing little bottles in the town. There was a shoemaker who always kept a little bottle of poison in his pocket. Once, the bottle opened in his pocket and poured over his foot. His pants were burned and his undergarments, and his foot began to rot. The plan of escape was postponed.

Later, there was another delay. They brought a dentist and his wife and child to us in our barrack who had been in hiding the shtetl of Gorodzie with Arian papers. They complained to them in the barrack, that they had no connection with Jews, and they were detained by mistake and they will certainly free them. In the meantime, it disturbed our plans.

However, we felt that the earth had begun to burn under our feet. Before this, a few of our workers talked with some of the policemen[13] that we should organise together and run away from here. Twelve police agreed. It was agreed upon that at a certain time they would occupy the whole courtyard under their control. We would harness horses and wagons loaded with guns. They would put down dynamite and immediately after leaving, everything would explode together with the murderers.

However, during the last days, the police retracted from the plan, not wanting to risk the lives of their families.

In the middle of March 1944, a Jew from Baranowicz was arrested. They questioned him about what we are talking about and what we do in the evening hours when everybody gets together. When they saw that he didn't want to say anything, they beat him to death with rubber truncheons.

A day later, a tailor from Slonim, who was at the head of our organized plan, was arrested. Fearing that our plan would be thwarted, at midday, we held a secret gathering and everyone decided to go to the forest immediately.

On 22 March 1944, the carpenters knocked out a wall, and at 11p.m. we left the compound. In pre-organized groups, we ran in different directions. We crawled one after the other, on our stomachs, in deep mud which doesn't freeze even in winter. We travelled rapidly, wanting to put as much distance between ourselves and the murderers as possible.

Our feet were breaking from weakness, but the impetus drove us and gave us strength. We could hardly

[Page 323]

believe and were afraid of the thought that we were free. We imagined that this was all a dream. We went past a non-Jewish house and we wanted to know where we were, but we were afraid to ask. Two of us decided to go and ask. The peasant answered that we are only seven km from our camp. According to our judgment, we should have been 25 km away. It appears that we got lost because the area was unfamiliar to us. The day began to dawn and we didn't know where to hide, and wondered where to spend the day until we came to a small hill. There we found pits and decided to stay until nightfall.

Our group numbered 32 people. At midday, we heard a few shots. Later, we became aware that the murderers were running to look for us and they came across another group of ours of 17 people. In that group was a man from Stolpce, Moishe Raizer, Yakov the painter's son. There, a shoemaker was provoked, seeing the murderers from a distance, so he shot himself with a revolver that he had and in so doing, revealed the whole group. Our group remained until dark. Two of our group volunteered to go and get information from the peasant's house, which could be seen from a distance. They told us we could confidently enter the house.

A watchmaker from among us promised the peasant a watch if he would give us all a piece of bread, and two boiled potatoes. We swallowed it down, stilled our hunger a little, and we hid ourselves in a horses stable huddled together until 11p.m. The peasant showed us the way and we allowed ourselves to continue our journey. Some of us already had swollen feet and couldn't walk but the impetus carried us and in a few hours, we came to a small wood. From a distance, we again saw a peasant's house and went to the window to ask directions. The peasant told us that today, three thousand Cossacks from Horredicz who served the Germans, passed through looking for us. He advised us to stay over somewhere in a little wood and not to dare move out. The peasant also gave us a bread for everybody. We debated what to do and decided to stay over in the little forest.

The next night, we went by chance into the same house and the peasant told us that the Cossacks had already turned back. He again gave us bread and we went away. During the night, we came to a place where, quite early, we suddenly met a patrol of two Partisans. They didn't receive us very nicely and kept on asking us what we are doing here and from where we have come. When we told them our story, they interrogated us: how did we manage to stay so long in Kolditzeve helping the Germans to produce armaments in order to fight against the Partisans. When we heard them speaking, we were shocked and frozen; not enough that the Germans are murdering Jews, should Partisans also shoot Jews!... After a short exchange with them, they asked us if we could perhaps give them a watch or a little money. With that it appears, they were pacified and we were overwhelmed with joy, that we were able to buy ourselves out with this. Later, we got to know that according to Stalin's decree of 1943, nobody was allowed to be shot in the forest.

In order to reach the right Partisans, we still had 50 km to go until the Naliboke plains.

After seven days of suffering from cold and hunger, wandering the whole night with our last strength and swollen feet, we reached the first patrol of Bielski's Partisans. This was at 2 o'clock at night, 1 April 1944.

There we met two Jewish Partisan groups: In Beilski's group there were 1200 people exclusively Jewish, in Zarin's group there were 600 Jews. In both groups there were people from Stolpce.

In Zarin's were: Yaakov Levin his wife Sonia and their son Dutke, Daniel Horenkreig, with his wife and two daughters, Peishe Epshtein from Swierzne and Pekker Yaakov with his son Joshua, Meishel Tunik Etke's son. (Yaakov Pekker and Meishel Tunik died just before the liberation in a battle with the Germans. His son Joshua Pekker fell as a hero in the War of Liberation in Israel). Eliezer Reizer and his son Yisrolik, Dovid Slutzak with his wife Freda, Mendel Eisenberg, Eli Bruchansky (Shimon Chatzkel's son) and his sister, Sholem Ruditzki, Etel Uskern, Isser the carpenter's son from Uzde[14].

In Bielski's group were: Malbin who recently lived in Novogrudek, Yone Bernshtein, Tamar Amrant-Rabinowicz, Luba and Chana Axlerod, Rivka Kantarowich, Tsvi Stolevitski (Eliakum the scribe's son), Esther Bercowicz with her brother, Beryl Krinitzner (Berel Faive's wife), Yaakov Koshtzewicz (Yisroel Akiva Rosovsky's son-in-law who lived in Rubzevich), with his daughter Lieba Tzuker and her husband Zalman Aginsky. Nine of the people of Stolpce in our group, that means, the group that worked in Baranovich at the S.D. labour camp until the transport to Koloditzeve in November 1943. Baruch Ozer Akun's three sons who were carpenters: Zalman, Hillel, Beryl and Mosie Sargovich (Hillel the carpenter's son-in-law), three carpenters who were not born in Stolpce (refugees), two brick layers, Getzel Reiser and Moshe Reiser – Yaakov the bricklayer's sons.

[Page 324]

These are the Stolpce people we met in Kolditseve; Leib Aaron Gruness, Velvel Slutsak a leather worker, Yoseph Charne (the Swierzne leather worker), Chaim Kaplan (Shifra the bathhouse attendant's son), Yona Bernshtein, Yaakov the bricklayer's two sons Nochum and Eliahu and their brother-in-law Meir the tailor.

A few words about Velvel Slutzak; he worked as a tanner as a very skilled tradesman and the police were exceptionally pleased with him. He was a strong man. Once he did not complete a job exactly at the appointed time so the Germans came to ask about the work so he asked them: leave me and I will finish the work in the late hours after my workday. From the beginning they agreed to this but later they reconsidered: no we must punish him. Two White Russian policemen approached him from behind as he sat working grabbed a 15 cm long needle for leatherwork from the table and pushed the needle into his shoulder. He almost fainted but from shock he asked for a little water and wanted to continue working. He felt he was being drenched with blood and he came to the barrack. There Dr. Levinbuk tried to stem to flow of blood but he became sick and in great pain he passed away.

It is worthwhile to note the following about Chaim Kaplan: he was the man responsible for the carpenters. He could move around more freely than others. He used to be able to go to the nearby villages with a pretext that he is going to provide and prepare material for the work. Once when he was returning from the village the police noticed he is carrying a bread in his sack so they called him to come over to them. They set a big angry dog on him until it tore him to death.

Quickly they instructed two Jews to cover his body with snow. He lay there covered until the snow began to melt in spring then the police again took two Jews, told them to dig a grave in the middle of the yard and they buried him there.

While Leib Aaron Gruness was walking in the first row with courage in the last death march, he took up the command casually calling out “Shema Yisroel”

G-d our King we will revenge for the spilt blood of Your servants.

|

|

Seated from right: Feiga, Freidl Reiser,Toibe and Yossef Russak, Getzel, Shaul-Ber, Minah, Leib Meir Reiser Standing from right: Eliezer and Sara Yessel Reiser |

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 325]

by Shmuel Leib Aginsky

(may his memory be blessed)

Translated by Libby Raichman

In 1941, when the Nazis confined the Stoibtz Jews to the ghetto, the hardship and the suffering was enormous. The Germans beat and killed, and life was intolerable. A few Jews tried to run into the forests, but they were not familiar with the area.

In the Stoibtz ghetto there were those who smuggled in guns and bullets. We hid them in Leizer Zaretzky's cellar - in total 13 guns and 2000 bullets.

I turned to the gun collectors and explained to them that being experienced and knowing the route to the Partisans, I was prepared to go with them to the forest. It was decided that at 12 midnight, they would bring the guns to the back of the stable of Yankel Berel, the carpenter, that bordered the fence of the ghetto.

Leizer Zaretzky the wheelwright, cut the wires of the fence and Yosef Harkavy and I went out first.

We were really lucky, and fifteen men and three women left the ghetto. We followed the Setzkiye Highway to the Zadvoriye railway line. As we had to cross the tracks, our friends sat down to rest near Kaveloyishtshinne Street while Yosef Harkavy and I went to survey the surroundings.

At a distance we noticed a few Germans and along the length of the railway line and peasant guards were also standing there with sticks in their hands. So, we lay down next to the line and as soon as a train came into view, we crossed the line behind it. We were noticed, and they tried to find us with flares, but we had already reached the nearby forest.

We avoided the wide roads where the Germans marched and travelled. We walked the whole night until we reached the former Russian border. There we stopped in the forest for the whole day, and at night we passed through the village of Prushvenovve.

Not far from there, in a hamlet, lived an old Christian lady, a good acquaintance. I went with Yosef Harkavy and Ezriel Tunik's son Hirshel, to find out from her from what was happening in the district.

When the old Christian lady saw us, she came out looking fearful and did not answer our questions. We noticed however, that 3 revolvers were protruding from the second room of her house. We loaded our rifles and I said to Ezriel: switch on the flashlight! To our astonishment, there were 3 Jews there: one from Stoibtz and 2 from Warsaw. Shniur Bernshtein, the son of Itshe Bayle Etkes, recognized my voice. The other 2 were Yosef Reich and Hershel Possesorsky. They told us that they had been working for the Germans at the railway station and fled into the forest, taking with them 5 pistols that they stole from the Germans. By accident, Possesorsky was wounded in the foot, from his own loaded revolver. They had been lying close to the old Christian lady who brought them medicine from Uzre. We decided to go on our way together. We made a sort of stretcher from wood for the wounded man. We walked for 4 kilometers until we reached Mogilne. Approaching the Niemen River, we saw that the bridge had been burnt down so we made a sort of raft out of wood that carried the wounded man and the women across the river. The men crossed the river naked. We did not go into the village. We lay behind the village of Motetzky the whole day and gathered food. At dusk we went back into the village and from there, arriving in the first village, we took a wagon for the wounded man. In this way we went in the direction of Pesotshne. In this village, we met up with the Partisans. They allocated us, 3 to a house. They gave us food and allowed us to rest for a day, and then we went on our way to Zshukov's military detachment. When the Partisans at the detachment learned that Jews were arriving with guns, they received us with joy. After resting for a couple of days at Giltzik's Partisan detachment, we told them that we wanted to turn back to Stoibtz again, to rescue people and bring more guns.

A group assembled, consisting of 6 people from Stoibtz and another 6 Christians and eastern-Jews -- that meant Jews from eastern White Russia. We reached the village of Prushvenovve travelling in 2 wagons and went to a peasant farmer with whom we were acquainted. He asked us: how did we travel into the village that has been full of Germans for the past 2 days.

Somehow, we left the village and travelled into a thick forest. We remained there for a night and a day. Our group was displeased with me – why did I bring them to the Germans? So, Harkavy and I proposed that we should take a vote – who wants to go to Stoibtz and who wants to turn back. Only 6 voted for the proposal to go to Stoibtz. The other 6 acquired a horse and cart and turned back to the detachment.

On the way to Stoibtz, we sent a pregnant Christian woman to Stoibtz with a letter to Yakov Levin. He

[Page 326]

wrote to us, that after we left Stoibtz another slaughter took place. They only left behind “necessary” Jews. They would have liked to join us, but it was impossible to cross the railway line. However, we spent 2 days and 2 nights near Artzechier village, and nobody came. On the last night we went into the village and took 6 horses and pelts and wagons and took them to the detachment.

We sent a letter with the Christian woman to tell them where we were. Yache Altman forwarded the letter to her husband Kushe Altman in Baranovicz and as a result, 50 Jews from Baranovicz joined us in our detachment in the Yoveshtzer forest. Amongst them were also a few Jews from Stoibtz.

In January 1943, a Stoibtz group left to free Jews and acquire guns. The group found itself in the village of Faharelle, 12 kilometers from Stoibtz. The courageous partisan Possesorsky, dressed up as a peasant farmer from the village, with bread, a piece of butter and eggs and reached the Swerznie sawmill. Jews worked there and he said that he wanted to buy wooden boards. After giving the German guard a couple of eggs, the guard then allowed him into the sawmill. At lunch time, the Jews took Possesorsky into the camp.

A heavy snowfall and a storm that night, gave the Jews an opportunity to cut the wires of the fence and 250 Jews went free. Half of them went to other forests and those remaining came to us. As soon as we heard about this, riders were sent out to bring in, those who escaped. In the meantime, we harnessed all the horses that were in the village and went out to meet the escapees and put them into the wagons.

We took 30 wagons from the peasant farmers in the village with the promise that they would be returned. The promise was fulfilled.

When the Germans found out what had happened, we had already travelled 50 kilometers deep into the forest. When we arrived at the detachment, the managing committee called us together and complained because we had brought 125 people, and not one gun, to which we answered and stressed, that we would not send anyone back, but that we would go out in groups and find ways to acquire guns. At the head of one of the groups was the famous partisan Possesorsky.

On the way he met a partisan belonging to a group of Murder-Commandos. Possesorsky had a German farm-hand with him who he took from the Germans when he fled into the forest. The commander demanded that he hand over the farm-hand. To this Possesorsky replied: You are a hero to take away what is mine; to show courage, take from a German but not from me. The commander gave him an ultimatum of 5 minutes, and if not, he would put a bullet into him. Possesorsky did not believe that he would shoot him. That murderer shot him dead.

At the head of one group stood the young hero Ozer Mazze, who always advanced ahead under a hail of bullets, until he fell. When they received some arms, the Jews who were freed formed a company of fighters.

Stoibtz Jews were not able to sit idle and they again sought means of freeing Jews from murdering hands. A group of Stoibtz fighters organised themselves; their leaders were: Lachovitzky, and Vishniyo from Baranovicz. They were well-informed and very familiar with the roads to travel and their destinations.

At a distance of 100 kilometers from the camp, a large group went out, but on the way, we separated into 2 groups: Lachovitzky with 6 residents from Stoibtz, went towards Baranovicz, and my group remained to provide food for the detachment.

The first group came to the cemetery in Baranovicz. There they met a Jew who advised them to go to the bathhouse where they would find another Jew who would help them.

So, they left their guns in the attic of the prayer house at the cemetery. The Jew at the bathhouse received them well and gave them a room in their camp. Israel Machtey (Reuven the tailor's son), undertook to go into the enemy camp, so he put on a dark fur and a fur hat and smeared his face with soot to look like a railway worker. He went to the Palyesse railway station, where Jews from Stoibtz worked. He had in his possession, 4 hand grenades and a revolver. It was a matter of life or death.

On arrival at the railway station, at 8 o'clock on a winter's night, he approached the German, the guard, and said that he worked on the trains and that he had come from Stoibtz where a Jewish woman had given him tobacco for Hirshl Tunik (Feige's son), and that he wanted to deliver it to him.

They allowed him to go into the kitchen and he gave Hirshl the tobacco, and a letter, telling him that he should take a certain group of Jews out.

During the day, only 7 people left work and came to us, to the place where we were. The 7 were: Hirshl Tunik with his 2 sons, Leibe

[Page 327]

and Fyve, the 2 brothers Meir and Elimelech Machtey, Aharon Melamed and my son Tzvi Aginsky.

We did not rest, and we again organised a group of 8 members from Stoibtz. I was the guide of the group and Yosef Harkavy was the commander. The others were: Boaz Akselrod, Moshe Esterkin, Kushe Altman, Moshe Vineshtein, Shniur Berenshtein, Avraham Shulkin.

Our task was to burn down the sawmill in Stoibtz (that belonged to the Jew Kitayevicz) but was now managed by the Germans and Kitayevicz was now very useful to them.

They were called the heroic 8, whose aim and task was to rescue Jews. We were given the freedom to leave for 12 days. On the way we came across a camp of Germans and our situation was very bad. We were already 3 kilometers from Swerznie and 5 kilometers from Stoibtz. Somehow, we quickly and stealthily crept into a farmer's barn and lay there for a whole day. The Germans rode through endlessly the whole day, a day that seemed drawn out like a year.

We could hardly wait for nightfall. At 11pm we left the barn on our way to the railway line. Yosef Harkavy and I went to spy out the area and those remaining lay in wait. The two Germans who stood on guard, did not notice us, so we returned to our friends and crossed the railway line and made our way to the Stoibtz-Mir Highway and entered the Krugletze forest. From there we sent a peasant farmer to Stoibtz. He promised us that he would go as far as the Stoibtz sawmill and see what was happening there, but he did not return very quickly. The Germans beat him severely and arrested him. When they released him, he came immediately and told us, how the Germans are guarding against partisan attacks.

We decided to go to the Nalybokke forest, and to our misfortune we came upon a camp of a hundred Poles. They disarmed us but we immediately turned towards the Stalinske Brigade and when we showed our papers and where we were going, they returned our arms and our papers from the Polish headquarters and they also added that they would not hinder us and would help us in any way they could.

We went looking for Jewish groups in the small forests. We were told that Jews from Mir were in the Birshtanne forest. On our arrival there, amongst them we also found a few Jews from Stoibtz. They asked us to take them away from there, because, from amongst the village peasants close to the town, they sensed great hatred towards them. It was impossible to take everyone, as we ourselves did not know where we were going. About 12 Stoibtz residents came with us like: Yakov Levin with his family, the two Akselrod sisters, Horenkrieg with his family, Maishl Tunik (Etkes), Eli Bruchansky and others. We led them to the Nalybokke forest. We promised the remaining Jews that we would return quickly and take them out, because we had to get permission from the Russian military detachments to bring in more Jews into the forest. After travelling for about 50 kilometers, we learned that a group of 300 fleeing Jews, including women and children had arrived from Minsk. When we found their camp, we presented ourselves to their commander Zorin, and described what our task was. In answer to our request to allow the Stoibtz families to remain with him, he explained, that without guns, he could not keep anyone because they themselves have no rifles. So, we gave him two of our rifles and promised that we would bring additional guns for his division. In this way we managed to leave our Stoibtz people temporarily in Zorin's division.

We were a group of 8 Jews, well-armed and provided with papers of recommendation we arrived at the Rubzevitsh district and looked for Jews in the forests. I knew the area well so I went to an acquaintance, a farmer, and he indicated to me, the places where Jews could be found. When I arrived there, all the Rubezhvitz Jews with whom we were acquainted, rejoiced. They told us that quite close to them were a few Stoibtz Jews. There we met: Rivkah Kantorovicz, Sholem Ruditzky, Yankel Shmerkovicz (Berre Izis son-in-law), and Chilke, a refugee who lived in Stoibtz. They complained that the Russian partisans came often and tortured them. They were naked and barefoot. At night we went to a village and brought them clothes, bread and meat from there, and we promised to come and take them away from there.

As we made our way around the forest, we informed the leaders that there were groups of Jews in the forest. The commander of the entire district assembled the Jewish detachments, and the order was given to take in the Jews in the small groups, into their divisions.

Wagons were sent out to gather the Jews in the small forests. We still tried to cross the railway line to unite with our divisions, but we were showered with a hail of bullets. We left for the Stalin Brigade where we were welcomed as good guests. We used to carry out the most difficult tasks. Maishl Esterkin remained in the camp

[Page 328]

and 7 men from our group left in the direction of Chotevve. Hundreds of “white” Poles went out to fight with the partisans. A group of 30 partisans were surrounded; their guns were taken from them and thrown into a cellar. As we were of the last, 2 Russians told us that we were in danger, so we began to run into the forest. I was the first to run to the left and 2 more after me. The others ran to the right and fell into the hands of the bandits. They fought until their last bullet and fell like heroes. Regrettably, there we lost 5 Stoibtz heroes: Yosef Harkavy, Boaz Akselrod, Kushe Altman, Maishl Vineshtein, Shniur Bernshtein as well as a Christian.

Avraham Shulkin and I and another Christian, crossed over a huge swamp and on arriving at the detachment (division), we found no one because everyone went to fight against the Poles. Only women and the sick remained.

After a few days, we, a group of friends, went out to look for our Stoibtz friends, but we did not even find their bones.

The Red Army soon liberated all the partisans. Avraham Shulkin fell at the front lines of battle. I found my 16-year-old boy Tzvi, who I left in the forests.

I came to Stoibtz again and stood devastated on the graves of our most beautiful and best relatives and friends. The town had been burned down. We felt like living orphans at every step. Every step was dipped and soaked in Jewish blood. We looked for a way to run further. In Poland we did not find any peace for our broken spirits.

We came to the Land of Israel to fight for our own land. My son Tzvi Aginsky joined the Jewish Army as a volunteer and was wounded. Now he has the rank of Reserve Officer in the brave Jewish Army.

|

|

Sitting from right: Tanchum Esterkin, Moshe Esterkin, Shlayme Aginsky Standing from right: Getzel Reiser, Moshe Borsuk, Shmuel Leib Aginsky, Mendl Machtey |

[Page 329]

by Yosef Reich

Translated by Esther Libby Raichman

Yosef Reich, the author of the book “Forest in Flames, was a refugee from Warsaw, who experienced the cruel times in the Stoibtz ghetto and later in the forest. He eternalised the memories of those times in his book that was published in 1954 Buenos Aires (publishers Yidbuch).

In the confined framework of this “Memorial Book”, we bring only a few fragments of the above–mentioned book that should be read by every son of the town.

Editorial board.

On the 27th June the Germans occupied Stoibtz. During the first 2 days, the Germans did not bother the Jews.

On the 29th June 1941, early in the morning, we were surprised and astonished to hear loud shooting very close to us. Through the windows we saw the flames of the neighbouring houses burning and the first thought that came to mind was a pleasing one – that these were probably “ours”, returning from battle with the Germans. When I came outside, I was bitterly disappointed. The place was full of Germans, everywhere, whose appearance and manner did not suggest that there was someone in the vicinity who could have troubled them. In their hands they had automatic rifles ready to shoot. Their guns were aimed at men whom they had brought from different locations who were unprotected and scared to death.

Those who were brought in were united with the men from the camp, who were there earlier at a place on my right, surrounded by the SS guards with their guns raised. I wanted to go back into my house, and instinctively I shuffled to the left, clinging close to the wall of the stable, but it was already too late. Immediately two Germans emerged alongside me, and pushing me with the barrels of their rifles, they handed me over to another German who took me to the left, to a group of men who stood to one side, removed from the street and closer to the field. Our little group was smaller than the one that stood to the right and the attitude of the Germans to us, was not as severe as it was to them. It did not take long before we were taken behind the town to a field, where we were kept under guard. Constant shooting could be heard from the village and we were tormented by the question – what is happening there? We tried to find out something from the Germans who were guarding us. From their conversation, it appears that shots were fired through a window on Lenin Street (Minsk), at a marching military procession, and as punishment for that, the street was destroyed. After detaining us for a few hours, they freed us, and with all my strength, in one breath, I ran into the town.

Arriving in Lenin Street (Minsk), I was shocked at the devastation caused by the Germans in such a short time. This most beautiful and bustling street in the village, was turned into a cemetery that was full of unburied dead people. Not a living soul could be found to ask something or to find out anything. The only houses that were not set on fire by the Germans were devoid of people; everything there was abandoned, and Germans were also nowhere to be seen. All around it was quiet and still; one could not hear a sound or see any sign of life; everything was congealed and shrivelled, only the bodies of the dead men lying around everywhere, and the skeletons of the remnants of the houses that were still burning like candles for the souls of the dead, told of the crimes that were committed here.

With a trembling heart, I went closer to the place where my brother–in–law lived. A lock hung on the door and I sighed more lightly with relief – they probably went away somewhere – I thought – and perhaps were saved from death. I went out into the street, as if by someone's command, turned around and went back into the courtyard; I touched the lock again to see if it was properly closed and I looked into the window of the house. I looked around on all sides and did not notice anything unusual, but going further into the courtyard, I saw 3 dead people lying in the corner of the stable. Among the wooden beams that lay strewn around, leaning with his head on the wall of the stable, with a backpack on his shoulder, with a small blood mark on his left temple, laid my brother–in–law Noach Fish. His death must have come so very unexpectedly and sudden, that he became congealed and petrified in the same pose and with the same expression as if he were alive. He did not look as if he were dead, rather like a wax figure. Next to him, with their faces to the ground, lay his father–in–law Yitzchak Bloch and his brother–in–law, Stashek Bloch. A couple of metres from the trio, embracing, and with their hands intertwined, lay the dead bodies of the engineer Chaitowicz and his wife; this was the only woman found amongst the

[Page 330]

large number of people who were shot when the Germans first entered the town of Stoibtz. Then the Germans were still “gentleman like” and had respect for women. She probably did not want to leave her beloved husband.

In the middle of July 1941, the attitude of the military division that had just passed through Stoibtz, was worse than the previous one, and did not make the same impression as the first motorised storm trooper divisions. Many of these Germans liked to tell us about the fate that awaited the Jews. Most expressed themselves with brutal joy. A small part – casually, and many even with regret, all of them repeated the same: “we are the first, with us it is still not so bad; after us come the second, and they are worse for your Jews; then come the third, the last, then you are completely finished”. Some used to illustrate the word “kaput[1]” with appropriate gestures that presented graphically, how we would be “kaput”. At that time, I understood the word “kaput” in a more symbolic sense – finished – with your regime, with your rule, but not physical extermination. But as the tragic reality revealed, they knew what they were talking about and were well informed.

At the end of July 1941, the torture and plunder of the Jewish population took on a more organized character. A variety of signed demands was issued, with the arrival of the “local command headquarters” for example: labour duty for men between the ages of 14 and 60, and for women between the ages of 16 to 50, about wearing armbands with Stars of David; about the prohibition of purchasing from Aryans etc. What was strange, was the way the selection of the Jews for work, was organized. This was the picture that presented itself: In the centre of the town, opposite the town court, at the end of Minsk Street, was a huge square. This open square was on a higher level than the entire surrounds and gave the impression of being a specially erected platform. The Jews of Stoibtz would have to assemble at this place, at 5am every day. Poles like signposts with inscriptions were laid out across the entire length of the place, with numbers from 1 to 100, from 100 to 200 etc. until more than a thousand. Next to every pole, 100 people stood, spread out in 2 rows; men, women and the youth were segregated and stood in separate columns. Around the square were spectators from the local Aryan population. Amongst them were those who were simply curious who came to enjoy the magnificent scene, and also those who came “on business”, who waited to be allotted Jewish slaves, to work.

It did not take long before the local commander and his aides appeared, the “special commando” for Jewish matters. The leader, a folk–German from Latvia, who spoke good Russian, came out into the square like a wild animal that had just been released from a cage. He ran out wildly amongst the rows of people shrieking, screaming and hurling abuse, that cast a fear over everyone. For the slightest offence, and also for no reason, he slapped people. His slaps resounded and echoed over the entire place and we therefore nicknamed him “the slapper”. After this, the distribution for labour began. First, the German demand for Jewish workers was completed; they were used to lay railway lines, build roads, and to load train carriages to serve the military transports that were passing through. The women were used mostly for cleaning and washing laundry. Some Germans would come to select workers themselves and take them away with them immediately. Then some tried by different means, to fall into the hands of “good” Germans. By doing this, there were often fatal mistakes because the bad Germans often turned out to be good, and the “good” Germans, were bad. When the selection of Jewish workers for German requirements, was complete, they began to attend to the needs of the White–Russians who were of two kinds – for private persons, and for the town administration. The private person (only White–Russians benefitted from this privilege, not Poles) received Jewish workers to build houses and barns for them, and to assist with home maintenance and with their private undertakings. The town administration received Jewish workers to carry out all the heavy and dirty work that was necessary for the town. A special brigade of Jewish women was assigned to sweep the streets. Until the arrival of the Germans, Stoibtz was, by the way, a very clean town because every resident kept the area around the piece of ground where he lived, clean. The Jewish women had to sweep for everyone and most of the Aryans of Stoibtz, now being free of work, lived like nobility and enjoyed to the full extent, and undisturbed, the assets that they had pillaged from the Jews.

Today, 25th July 1941, the Jews of Stoibtz who had been choking and suffering in the hell that was created for them by the German torturers who had become so familiar to them, were shaken up by a new calamity that

[Page 331]

descended upon them. The demons of the Gestapo came into the town to do their “rounds” and they tore 90 new Jewish lives to shreds. It happened in this way: for a few days, I had already been working building a new road, together with another few hundred Jews, a kilometre behind the town. The work was very difficult and the pace, murderous. The road had to serve the march–through of the German military and had to be ready in a few days.

As we were walking back home, we reached the town, but here a tragic surprise awaited us, that made us forget about hunger and fatigue, and in one blink of an eye, knocked out of our heads, all sweet fantasies of the rest we had earned. In the middle of our path stood sudenikes[2] who had been awaiting us earlier, that stopped us and met us with a hail of blows. They sent away the Germans that escorted us and placed us under their authority. Accompanied by beatings and verbal abuse, they arranged us in rows. After that an elegant automobile arrived, and members of the Gestapo stepped out, and a selection began. They noted and considered everyone and made eye contact with each one and asked about their profession. Any one that they suspected of being intelligent, was removed from the row, and taken with them; and they were suspicious of Jews, on whose faces they noticed an alert expression, a grimace of protest or a dignity, an erect well–kept figure and a proud appearance. I heard one Gestapo say to another, pointing out a tall, thin youth that stood next to me, “that long one has such restless eyes”, and he was taken from the line. The first person that the Gestapo chose as a victim and removed from the line was the Stoibtz slaughterer, Reb Shlayme Ha'ari. This was a rare type of slaughterer and a rare type of person who was conspicuous, and distinctive in his appearance amongst tens of thousands. He was tall and broad with a fine blond–black beard and a pair of black burning eyes. Standing in the line, he was a head taller than the rest of us and gave the impression of being a strong oak, among undeveloped trees. After the selection of the best and most capable of us came to an end, we were beaten with sticks on our heads and chased further. After walking a distance, the same process of selection began anew; this was carried out by other Gestapo members. This was repeated three times and each time our rows were depleted by a few persons, and amongst those remaining, the number of those beaten and wounded grew. On that day, the same process was repeated amongst other groups of Jewish workers. Aside from this, various other people were removed from their homes, according to a list. All these people disappeared forever, without a trace. The place, and the manner of their death, remained the secret of the German hangmen.

At the beginning of August 1941, a new local administration came to Stoibtz that received the name “the Viennese” because the commander and most of his men came from Vienna. The take–over of the regime by the Viennese was splendid and evoked good hopes among the Jews of Stoibtz. After taking office, the new commander, a Viennese professor, in the role of Ober–Lieutenant, summoned the members of the Jewish Council, asked them to sit down, and spoke to them in a friendly manner and with sympathy. He was angry about the “barbarism” – that Jews had to wear special signs and he promised that he would try to revoke the “disgraceful” (his classification) decree. In the meantime, he made the first gesture and brought in lighter rules for the requirements for labour duties for Jews, than those that were issued by the former command headquarters. In this vein – only men between the ages of 15 and 60 were obligated to work, and women between the ages of 18 and 40. The members of the Jewish Council returned from the command headquarters in good spirits and were moved by the courteous and decent attitude of the commander. In these days of good hope, I worked at the headquarters as a tailor, working in the room of the new Sonder–fuhrer (special leader) for Jewish matters, named Koch, and I had the opportunity to see close up, the later execution of tens of thousands of Jews from the entire surrounding area. Now, for the first time the Jewish Council was approached, to carry out its actual role.

With regard to this, the residents of Stoibtz were agitated that the “refugees” had seized all the power on the Jewish Council, so they came to an agreement and the Jewish Council was reorganized with this in mind. As to the “refugees”, the chairmanship of the Jewish Council was now awarded to a new delegate who was a Stoibtz resident. Until then, the chairman of the Jewish Council was, a certain Vittenberg, a refugee from Lodz. He was a young man of about 30,

[Page 332]

an honest man with a good character but he had no qualification to be a social leader. He received the nomination for this position from the Germans, because of his attractive appearance and also because he could speak German well. This was a young man from the “golden youth” who could sooner be admired for his elegant manner and handsome appearance, than for his ability to be involved in social activity. It was a pleasure and a satisfaction to see him alongside the German rulers, always clean. Even in the worst times, he did not lose his manly splendor and charm and in the current period, the Germans with their race–theory, looked ridiculous. By chance, this elegant young man was placed in this position, for which he did not have the skills.

Pross, the new chairman, was a remarkably clever, capable and energetic person, a good merchant, inclined to big speculative business enterprise. Stoibtz and her Jews were too few to absorb all his energies and too small an objective for his ability. He understandably, soon became the actual head of the Jewish community. All the others were merely silent witnesses compared to him. The people of Stoibtz placed great hope in Pross. They believed that he, who before the war had conducted such huge business, and “involved with worldly matters”, would also find a solution with the Germans; but how could the sharpest mind help, the finest internal mechanism, the best head, when each and every German, the stupidest or the dullest, could at any time, at any moment, crush him. It could be, that the wisdom of an old and experienced people, with the ability to analyse too much, who with their thoughts, weighed and measured every possibility, was a misfortune for the Jews. In this lawless, Hitlerish time, one had to act according to one's instinct, like an animal, because being able to foresee, curbed the desire and restrained every act of defense and revenge.

The Jewish Council re–organized the work procedures in this respect – that every workplace should be as stable as possible; sending people to work should not be chaotic and incidental as it had been until then; every workman should be able to apply himself to the designated task directly, and should not be forced, as he had been until now, to arrive every day before noon at the work–exchange. This was a good outcome and a relief for the workman; however, it also had harmful side–effects because the conditions and the dangers in slave–labour (the workers were not rewarded at all) were not the same everywhere.

August 10, 1941. The days of good hope for the Jews of Stoibtz came to an end. The illusions about the “good” command administration vanished. Things happened that no one considered things that astounded and shocked the Jews of Stoibtz, like the outbreak of war, something that was inconceivable to the senses. The “good Viennese” were transformed overnight into the most terrible, bloodiest murderers. On that day, without any reason, they shot 2 Jews; they beat a large number of Jews murderously, at their work, in the street and in the houses. Again, old people and children had to go to work. Jews were forbidden to walk on the sidewalks, and instead of the commander's promise to abolish the compulsion to wear armbands with Stars of David, came the obligation to wear yellow patches on the shoulder and on the chest, as well as other decrees.

The biggest blow, one that was most shocking, was the arrest of the members of the Jewish Council who were reportedly, to be shot. This all happened so suddenly and unexpectedly that one's brains were spinning, and one almost went mad – not so removed from the physical shock as from the bizarre nature of the events. It was as if domestic animals were suddenly transformed into wolves, or as if dead objects had started to move.

The members of the Jewish Council were not shot and after being held in custody for two days where they were beaten and threatened with death, and where they were duly psychologically prepared to carry out their tasks in the newly developed conditions.

The command unit soon became infamous outside of Stoibtz too. Koch and his aides drove around like “tourists” in the surrounding towns and shot thousands of Jews. We used to see how they would drive out with empty trucks and returned with trucks full of the belongings of the Jews who were shot. Then we heard news that so many hundreds of Jews were shot in Turetz, Kletzk, Niesviezsh, Gorodie, Swerznie and other places.

Koch became as rich as Croesus and lived like an Eastern prince. The times when he slept on a cloth of peasant linen filled with hay and pleaded with me to find material for him for a suit – were already long past. Aside from Koch, amongst the “Viennese” there were hangmen, whose

[Page 333]

bloody images were tragically engraved in the memories of the Jewish population of Stoibtz. One of the most revolting amongst them was the “ginger”, by the name of Reichl.

This was a crude German soldier of about forty or more, a freak of nature, a sadist and a vampire, a very cruel character. Blood, tears and human pain, were his pleasures.

He was allotted a group of Jewish workers, and he became exclusively in control of them, and they served as material for his criminal instincts. Whoever fell into his hands, that person had already earlier, taken leave of his life, and if someone came out alive, that was a miracle. The “ginger” was the bloodiest nightmare for the Jews of Stoibtz on “calm days”. Not one day passed, that amongst the group that worked under his supervision, some sort of calamity did not occur – that someone did not return battered, broken limbs, whipped. Quite often, some workers did not return at all, because they were tortured by the “ginger”. The “ginger” never tired, was not idle in his work, he could not be bribed like the others. He did not need any gold, he did not need any other expensive items – all he needed was blood, the tears of his victims, his delight in their suffering, in their pain, and in their fear. This was the food for his sadistic inclinations. He did not take his eyes off his victims for one minute, but like a vampire he sucked their marrow and their blood. He was ingenious and inventive in torturing his victims, and he had a personal attitude to them. This is what once happened – he beat up one of his workers until he was certain that he was no longer alive but after that, his victim nevertheless, got up and continued to live. Reichl became so “moved” that he took him into his home, gave him food, and a pair of shoes as a gift. From then on, he generally had a better attitude to that worker than to others and favoured him.

Yet, with all these characteristics, the “ginger” did not possess the proper qualifications to be a mass murderer according to the volume demanded by the Germans, according to the German technique. It is paradoxical but it is possible, that precisely this sadism was an obstacle to becoming one, and he therefore, occupied himself only with small jobs. In his tally, he did not have tens of thousands of exterminated Jews, like his comrade Koch, but barely a few score.

Every decent and cultured German is capable of becoming such a criminal. All he needs is to receive an order and an appropriate dose of “ideological” justification that this is necessary and useful for the greatness of the Fatherland.