[Page 169]

On My Brother's[1] Death

by Isaac Berkovitz

Unrhymed translation by Harvey Spitzer z”l

I shall remember your face, my dear brother.

In my dream, I'll see your face from time to time.

This poem, in which there are tears and rage,

is formed from the rents of my heart.

I remember your daring soul

When we broke out of the narrow camp –

how determined you were!

My heart overflowed with so much pride after you.

And when the mourning overpowered us,

for we remained – the remnant of our people.

We were disgusted with life in this world

and then the commandment to live grew stronger.

We won't go to the slaughter like a flock of sheep,

although we have no other consolation.

Let's go out to battle,

to fight, to kill, to take revenge.

The murderer of your mother and sister will soon come to know you.

He will feel your fist – the enemy.

And he has drunk from the cup of your wrath

which is burning like fire.

Let's go to the people

who have drawn their swords to the enemy.

We will extend aid to these brave ones

And so we fought among their ranks.

Indeed, dear brother, we didn't know

and suddenly we heard

that there aren't many admirers

also among our friends.

If, from the hands of the enemy, you had fallen as a hero,

I wouldn't have cried, I wouldn't have shed tears.

For each of us waited his turn

for when he was to die.

But your friend[2] killed you

at whose side you went to fight,

because you didn't humiliate your honor

and you didn't forgo to those who cursed your people.

|

|

|

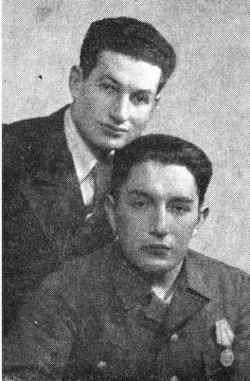

| Isaac Berkovitz (right) and Yosef Melamed (left) in Moscow at the end of the war |

|

And the hand of the murderers was raised

To kill you because you were ready to fight

against your enemy – who was also their enemy

on whom you declared war.

And also then you knew your way –

You didn't run away from the battlefield.

And alone you showed your murderers

that your blood would not be shed in vain.

And their contaminated blood diluted with your blood

was washed away at the same moment[3]

And for many days your enemy continued to tell

about the Jew who knew no fear….

Your memory, my dear brother,

will not depart from me as long as I live.

Your image will always be before my eyes

and my heart will weep forever.

Sleep, my dear brother, in the foreign land

which betrayed its children!

Cursed be that land – a cruel mother

who gave birth to your murderers!

I will bewail your death today

standing on the threshold of our homeland.

My agony will never be silenced

and your fire is burning in my blood!

|

Translator's Footnotes

- Although the brother's name is not given in the present text, Isaac Berkovitz has written about his brother Michael in the chapter “In the camp and the forest” (Original text Pages 140-145), and a description of Michael's death is given on page 145. Return

- Your friend – you are fellow partisan. Return

- Many non-Jewish partisans were hostile to the Jewish partisans and this seems to be the case here, where a Gentile partisan cursed the Jewish people and Berkovitz came to blows with him and was killed, while also killing some other Gentiles, as is alluded to here (“their blood mixed”). Return

[Page 170]

And You Shall Tell Your Son[1]…

by David Levin

Translated by Ann Belinsky

It is more than 20 years since the Holocaust and many concepts have become rooted in it, and even we, those who saw it and lived through it in all its cruelty, find difficulty in explaining the phenomena and even more, our behavior and that of our parents and those close to us.

Judenrat. – Can we, remnants of the Steibtz Ghetto, show restraint and admit that the term, Judenrat, is identified with all the negativity that was exposed so disgracefully in the ghettos? How can it be that the first Judenrat in Steibtz, which included the honorable of the congregation and its elders: my grandfather Yitzhak Yosselevicz, Wolf Tunik, Yeremiahu Pras, Tanchum Shulkin, Berl-Moshe Reiser, Lieb Kumak, and others, is it possible, that this Judenrat would appear and its memory be recounted as it is described in Holocaust literature?

I was 11 years old when the Germans invaded our area, and as far as I can remember – the Germans turned to one [of the townspeople], who was appointed by them as Mayor, and ordered that he would “recommend” the establishment of the Judenrat. This same Gentile too, could not understand the intentions of the Germans and recommended 12 of the community's dignitaries.

And thus after a brief action, the members of the Judenrat objected to a murder committed by German soldiers. For this, members of the Judenrat were arrested and thoroughly beaten, until my grandfather and the other too became sick for many days.

I remember: that at the head of the Judenrat stood Vitenberg, a pleasant man, educated and honest, who came to us as a refugee from Central Poland. When the Germans executed 20 people who had been randomly caught on the “parade” yard, Vitenberg tried to resign. He and his deputy Wertheim tried with all their might to lighten the anxiety and the suffering of the Steibtz townspeople. I knew these people well, they would come to our house, and my grandfather's house, to deliberate and consult. They took the advice seriously and willingly looked for ways to help.

Even the Judenrat after the massacre, the same above Judenrat that guarded my father, so that he would not leave to the forests and would not take others with him (I attacked one of them with my fists, and punched his face because they stopped us from escaping), I think they were convinced that their actions were for the best for those remaining in the ghetto. They were sure that the survivors would remain alive in the ghetto. They wanted to save, as many as possible and not only themselves, and like those who hampered the rescue operations, they did it not out of malice, but to save.

Did We Go Like Sheep to the Slaughter?

Did we go like sheep to the slaughter? I will not compete with greater and cleverer people than myself, and according to my humble opinion, I will answer this painful question from within the trembling of my soul.

Over a period of a few years, I saw powerful countries collapse. I observed in full splendor the defeat of the Russian, German and Polish armies. Were they heroes in their victory and their defeats? Were not thousands of humiliated and depressed Russians led, accompanied by very few sentries? And the Germans? When they withdrew, were they not led, depressed, by Jewish partisans sons of the same inferior race in their eyes?

Indeed, not only we were led like sheep to the slaughter, for the defeated are not difficult to lead. And how were we led?

The Germans conquered our town on 27 June 1941. They cast their terror immediately with their arrival, and in the first days, they killed every man they came across, without any “check” of his Jewishness. Afterward, the humiliations began: prohibition of walking on the sidewalk, wearing identification ribbons and the Star of David, and forced labor.

What was our feeling? And what were the possibilities of resistance and the chance of success?

It was at the height of the war between Germany with mighty countries, and then they claimed: is there a sense in defending ourselves when the conqueror is “Mighty in Sovereignty.”[2] The hope of ending the war, and the feeling of “temporariness” of humiliations, strengthened and encouraged the possibility to endure them. Thus, a sort of philosophy was created, which said that the less that we disobey the humiliating orders, there will be more chance of getting through these events and the end of this period.

Despite being cut off from the rest of the world, rumors of mass annihilations came to our ears. These rumors indeed were always accompanied by excuses and “reasons” for murder. Reasons, so to speak, which, for some reason, did not seem logical that we too would drink from the cup of affliction. After all, in our town, there are many places of work which are essential and important to the Germans: the railway, sawmills, etc.

In the summer of 1942, young people began to smuggle weapons and tools of arson and destruction into the ghetto. In most homes, benzene bottles were also prepared to set on fire and burn down the houses.

On one of the summer days, the Germans demanded hundreds of youth for work outside the city. The youth demanded active resistance, to destroy the ghetto, to take out the few weapons they had, to burst out and escape, for, in any case, there was no sense in sitting in the ghetto, whose end would be annihilation.

The argument was animated. In the ghetto at that time, there were families with children and old people, and the question arose: is there logic in awakening the anger of the victors and to cause annihilation, while hope still exists that the war will end soon, and with it, the cancellation of the terrible edicts.

Details of the argument are not clear to me, but I remember the great emotion. In the end, the youth gave in and hundreds of them left according to the German order. When letters were received from those who were sent, and it was even confirmed that they were in a work camp – the area was prepared for another group to leave. Thus, the Germans were able to carry out their scheme and the “slaughter”, which took place on 12 Tishri 5703 [23 September 1942].

Even then, and during the whole time before, many efforts were made to hide from the evil eye. And indeed, hundreds of the ghetto inhabitants hid from sight, but the murderers – with meticulous searching found and discovered almost all those in hiding. There are also cases known of opposition and of burning down houses – but these were isolated incidents.

The weapons that were stored by other young people – some were found later and some were certainly buried and hidden somewhere to this day.

The hope that “the danger will pass” – is what lulled the ability to resist. And apart from that, the calculated German methods, which were supported by a huge organization searching for ways of destruction and their improvement technically and psychologically, were the elements that abolished the urge to resist. But, in another framework, both the partisans and the army of the Allies, and afterward here in our country [meaning Israel], the same Jews carried out acts of heroism and sacrifice, of honor and praise, in the establishment of the state.

Translator's Footnotes

- Exodus 13:8. Return

- First words of a traditional song, Ki Lo Naeh, from the Passover Haggadah, describing and praising G-d. Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Stowbtsy, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Jan 2024 by LA