|

First article title: Real Work Is More Important than Politics

Second article title: From Here and There (Reflections)

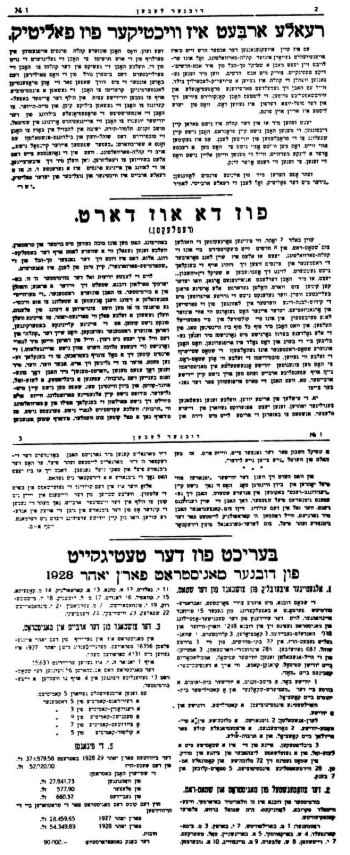

Third article title: Report of the Activities of the Dubno Magistrate for the Year 1928

|

|

[Column 603]

by Eliezer Steinman

Translated by Pamela Russ

[ ] translator's comments

The Scholar in His Town

Reb Yakov Krantz was born in the town of Zhetl, in the province of Vilna, and he died in Zamoszcz, Poland. He was the Maggid in Miedzyrzec Litovsk, and in Zulkiew [Zolkwa], Galicia. Of his sixty–four years of life, only eighteen were spent living in Dubno, and even in that time, he wandered from town to town and from country to country to give his lectures – nonetheless, his name and the city of Dubno are closely etched in the memory of generations.

[Column 604]

It seems that this city had a special merit, that its name should be part of this exceptional scholar's name, and Reb Yakov Krantz also had the great merit to become world renowned now with his own name and not with the name of his book Ohel Yakov [“The Tent of Yakov”], but actually with the name of his town: the Dubner Maggid.

We find that the Jewish scholars are named according to their compositions, such as: Rashi [Reb Shlomo Yitzkhaki], Rambam [Reb Moshe ben Maimon, Maimonides], Maharsha [Shmuel Eidels], Taz [Reb Dovid Halevi],

[Column 605]

Shakh [Reb Shabtia Hakohen], Node Beyehuda [Reb Yekhezkel Landau], Karti Ufalti, Shagas Aryeh [Reb Aryeh Leyb ben Asher Ginzberg], Mishna Lamelekh [Yehuda Rosanes], Maharam Schiff [Meyer ben Yakov Hakohen Shiff], Ohr Hakhaim [Reb Khaim ibn Attar], Alshikh [Moshe Alshikh], and more and more. And there are others, with names of the cities, such as: the Maharal of Prague, the Vilna Gaon, Rebbi Yisroel of Medzhybizh, the Miedzyrzecer Maggid, Reb Levi Yitzkhok of Berdichev, and Reb Nakhman of Breslau. The Dubner Maggid occupies a highly respected position among the scholars of the cities.

What are the differences between all of these? The greatest wonder is that if we would pay attention to all these scholars of the cities mentioned, other than the Vilna Gaon, the majority of these did not spend most of their lives in the cities in which they became famous. The Maharal, at the end of his life, already close to his eighties, took the Rabbinic seat in Prague; the Baal Shem Tov became famous before he arrived in Medzhybizh; Reb Nakhman was born and died not in Breslau; Reb Levi Yitzkhok became Rav in Berditchev after he held the Rabbinic seat in several other cities. The same is true for the Maggid of Dubno.

So, what is the reason for this?

We feel there is a reason for this.

The scholars of the cities were the majority of people whose main wisdom really came from the community's wells. [These wise men] appeared to the masses not as instructors or punishers, but as comforters and forgivers. They were more readily messengers rather than educators, and the more that was demanded of them, the more they would give, and with a new light they would shine upon the lives of the people and the individuals. They would remove a heavy burden from the soul of the people and reinforce the renewed souls. We find all these wonderful properties also in Reb Yakov Krantz. He was a man of Torah, but the main thing – he was a man of wisdom, a preacher of morals. But before anything else, he brought comfort. While standing at the tall lectern for a sermon, at the same time he came down to the people and saw the pain of the People of Israel

[Column 606]

and each individual person's anguish as well. He sat among the people and he spoke in his spirited language. He did not dress in a specific garb [with a specific title] – not a Rav, not the leader of the community, not a financial provider, not even a guide. He was a simple Jew who wandered on the roads, and did not admonish Yakov and Yosef about their sins, but showed them in their language that Yakov would be elevated even if he was small, even if his problems and enemies were many in number, because his faith and God's loftiness would not let Yakov fall – this was his protection [shield]. But along with the flow of faith that ran through his sermons, at the same time there was a call to the righteous senses that obligated one to admire the Tzaddikim [righteous scholars] and take revenge on the evil people. And an assistant to these senses was the merciful heart that provided justice.

The Dubner Maggid was the scholar of the heart. Mercy is the basis of the scholar of the heart. Just as Reb Yakov Krantz was not a Rav or a Dayan [religious judge], in the same way he did not usually sermonize or pass judgement on Jewish law. His heart was filled with mercy, and those merciful people are always humble. What makes one person consider himself loftier than the other? Is it the advantage of money and wealth, the advantage of strength and knowledge, or some other wonderful property? But a kind–hearted person does not consider himself great because of the virtues that he has – and not what another person has. If he is a real scholar, then he has mercy on those who are not so filled with Torah as he is; if he is a scholar or a sage, then he feels sorry for those who have been passed over by the light of Torah and charity. More so, the one who has mercy is always moved in his heart and he has no time to acknowledge his own importance.

The Dubner Maggid did not know at all that he was the Dubner Maggid whose name would resonate for many yovels [one yovel (jubilee) is 50 years]. He did not recognize his own spiritual characteristics. It probably did not even occur to him that he was the only one in his generation, and certainly not – one in many generations. He did not have time to be impressed with himself.

[Column 607]

His essence was thoroughly infused with the wonder of the Holy Creator, with the People of Israel, with the lessons and commentaries that were kept in his mind as if in a drawer. He was the strongbox for the seekers of truth, the father of the new homiletic, and with his new parables that sprouted with fine tales of life, he laid the building blocks for the new Yiddish literature that reflected reality. But he did not know that. There are some Gaonimwho know themselves, and there are some who are totally naive. He was completely artless. He was either the smart simpleton or the simple scholar – somewhere in those terms. His great humility also fed off his tremendous sincerity. In his talks with the Vilna Gaon, he compared himself to a poor man, without any particular recognition, no great welcome. And he was not seated at a table, but he stood like a poor man at the doorstep, or somewhere in a corner. He was not given a special plate, a spoon and fork, but he carried everything with him that might come into use, without any order, without a sooner or later, a piece of baked chicken, or a piece of herring. He ate the leftovers. “That is why he is not competent to write a sefer [religious book] about the portions of the Torah in order, but he jumps at every novel idea that comes from Heaven, be it from the Parsha [portion] of Balak, or from Yeshayahu. He sustains himself from the opportunities of life. He also considers himself as a guest in transit that jumps onto every wagon he meets and goes wherever the wagon driver is going.”

All the parables of the Dubner Maggid express

[Column 608]

a complete moral lesson. But the parable for himself as the poor man – does not fit. He was rich in spirit, and an exceptionally organized person. He did not just grab onto something and say it, but everything was weighed and measured. In the majority of his parables there are poor people, because his heart and spirit were with them, and with the poor nation. He was close to the simple people, one of the Jewish people. I imagine that the Dubner Maggid did not shout at the podium, but spoke proudly. He gave blessings and did not thunder. The humble person does not like to provoke. No, he was not a loud person, but the voice of the people – the people spoke through his throat. He spoke not only to the people, but from the people. Every honest prayer leader fears the congregation who sent him up as a representative [for the prayers], hardly sensing his own obligation as it should be.

The heart of the Dubner Maggid trembled, but the heart of the people was filled with pride, hearing his beautiful words. At that moment, the people heard their own voice, the voice of their forefathers across the entire Exile, the voice of the future generations that await liberation and redemption. Reb Yakov Krantz was a full–rich voice for his people. A voice of a bride and groom, a voice of the prayers, and a voice of the dances on Simkhas Torah. A voice of the nests and tides, a voice of joy and a voice of happiness.

The Maggid of Dubno means a Maggid for the people. Dubno merited that a Maggid of the people should live there. And so the capital of Dubno was a city and mother for Israel.

Translated by Pamela Russ

[ ] translator's comments

The Parable with Diamonds and Herring

In a town, there once lived a successful merchant, who was a scholar and a very smart man.

[Column 608]

He noticed that there were wealthy people living in the town, really rich people. He opened a diamond store for them and he had many customers. But some time later, he settled in a small town and many poor people lived there, paupers really poor people, sadly, poor devils, so sad. So the smart merchant went and opened a store for them. Not an ordinary store, but a store of herring, of salt, of kerosene, of other basic material. And the hands that used to hold diamonds, these same hands now held herring and some kerosene. And just as the merchant was satisfied with the other store, he was now happy with this poor store. No, he was even happier. He bore everything with joy.

That's how it went, until a friend of his from the larger town approached him and said to him:

“I don't understand. How is this fitting for you, for a diamond and jewel merchant to deal with herring and salt and with other simple things?”

The good and smart merchant replied:

“It's not good that you don't understand. Listen as I explain what this is: In the large city, there were people with lots of money, with their own diamonds, and they were very knowledgeable about expensive jewelry. But here live poor people, simple workers who sadly work and struggle very hard. They don't need diamonds and they don't understand anything about that. What they do need – is a small piece of herring, some salt, and a small piece of bread.”

This allegory, the Dubner Maggid sharply imprinted on the mind of the arrogant scholar who was preparing himself for the ordinary people with this scholarship.

The Blind Man and the Seeing Man

It is told:

The Dubner Maggid was asked why a rich man would give a contribution more readily to a blind, poor man, or a lame man, or a limping man, before giving a contribution to a poor man who is a scholar.

The Dubner answered briefly and sharply:

[Column 610]

That is because the rich man himself is not certain that he himself could one day become blind or lame. But one thing he is certain: He will never be a Torah scholar.

A Fool Does Not Know What He Is Missing

The Dubner was asked:

Why is the Maggid seen going to wealthy people, but you never see the wealthy person going to the Maggid?

It's simple. The Maggid knows well that he has no money, so that's why he goes to rich men. But the rich man does not know that he is missing Torah, so he never comes to the Maggid.

A Court Case with a Horse

Once, a modern person said to the Dubner: “So, let's test each other, and we'll see who is right.”

The Dubner looked at the rude person and said, in his usual manner:

“Young man, I'll tell you a parable about this:”

“Once, a Rav was riding with a wagon driver to Vilna, and the horse had to pull the wagon across a very hilly road. The driver went down off the wagon so that it should move more easily for the horse. Immediately, the Rav also went down off the wagon. And the driver said to the Rav:”

“‘You can stay in the wagon. You are a passenger and you paid for the ride.’”

“The Rav answered: ‘But the horse can have a complaint against me, that it is a huge hill, and he can summon me to Jewish court. I might win, but I do not want to go to Jewish court with a horse.’”

They Are All Right

The Dubner once said:

“It's a strange thing with the chassidim. If I am speaking to a chassid from Kotzk, he wants to offend the Rebbe from

[Column 611]

Monastrycz. If I am speaking with a chassid from Medzhybizh, then he wants to defame the Rebbe from Rydzyina. One does not believe the other. I, however, believe all. They are all right…”

The Wise Man and the Evil Man from the [Passover] Haggadah

They once asked the Dubner this question:

“What is the difference between the question that the Wise Man asks in the Passover Haggadah and the question that the Evil Man asks? It's almost the same thing. If that's the case, why should they call the Evil Man Rasha, and why should they push him away and almost curse him? What does the Wise Man say? He says: ‘What are the witnesses, and the laws, and the behaviors that our God has instructed you?’ ‘And what does the second Son who is called the Rasha, say?’ He says: ‘What is the worship that you are doing, what does it mean?’ There is really very little difference in their words.”

The Maggid replied:

“I will present you with a parable for this. Once, the Sultan dreamed that he lost his teeth. He asked his wise men to interpret this dream. One wise man said to him: ‘The dream means that your wife, your children, and all your good friends will die within your lifetime.’ The Sultan became very angry with these words and he demanded that this man be put into prison. After that, the Sultan asked another wise man, and that wise man replied: ‘The dream shows that you will live a long life and that you will outlive your wife and children, and all your court friends.’ These words pleased the Sultan greatly. Only later did these wise men realize that the only difference between the two messages was the tone and manner of speech. The first wise man delivered the message in a negative way, but the second wise man expressed the same idea in a positive manner.”

[Column 612]

“From that,” concluded the Dubner, “you see the difference between the first two sons of the Haggadah.”

From this parable and moral ending, you can see the Dubner's manner of Mussar [admonishment], and his manner of speaking to the people. Always better to take a positive outlook rather than, from the outset, complaining in a negative manner.

A Peasant in a Handsome Coat

Once, a peasant came to town to buy a few things. It was a cold, winter day. The peasant was wearing a warm, old fur coat, and under the coat he was wearing old, shabby clothing, and on top of that, he was wrapped in rags, all to keep warm. He sees a store with beautiful, warm clothing. He looks, and says to himself: “If I would put on that beautiful coat, I would look like a dandy, no worse than Prince Enescu.”

The peasant goes into the store and asks for a nice, black coat, just as the important people wear.

The smart storekeeper soon sees what size the peasant needs and so he gives him a coat and takes him into a separate room to try on the coat.

The storekeeper waits a minute, then another minute, and the peasant does not come out of the room. He goes into the room and sees how the peasant is struggling to get into the coat – but he is not succeeding. The peasant begins to shout: “What kind of coat did you give me? It is not my size. Are you making fun of me?”

The storekeeper replies:

“I am not making fun of you, but you are making fun of yourself. The coat is exactly for you. But before you put on such a coat, first you have to toss off your own fur coat and all the rags that you are wearing.”

[Column 613]

This is the parable, this is the story.

And what is the moral of the story?

The moral can be a simple one, like this: If a person does not toss off the coarseness from himself, then he can never become a respectable person…

But the Dubner made the moral a deeper one. He placed the moral onto the People of Israel, and with his warm melody, he began to say:

“And here is the moral of the story, which is telling us this

[Column 614]

The Holy Torah and its commandments which God, may He be blessed, gave to us, was appropriately created for our use, according to our nature and our needs. But we place all kinds of rags onto ourselves, all kinds of bad habits and bad sins. Then we complain that the Torah does not work for us, and that it is difficult to keep all the commandments. Rabbis! Leaders! First, let us throw down the rags and only then will we be able to see that the Torah is perfect for us…”

Original Footnote

[Column 613 Yiddish] [Column 174 Hebrew]

by Yitzkhok Aizik Feffer

Translated by Pamela Russ

In the year 1880, when I was eighteen years old, after my marriage to Khaya Laya Rinzberg, I left my hometown Olyk, not far from Dubno, and settled in Dubno proper.

Unlike the regular life of the youth in that period, who for years used to eat kest [regular meals as part of the dowry] at their father…in…law's home, and who spent regular time at the Beis Medrash [Study Hall] and in the kloizen [small Chassidic circles or courts], I went to work in trade, being certain that I would earn a living from that.

At that time, the main business for the Jews of Dubno was stores and shops. Rent for one such store was generally about six ruble a year, and the value of an average shop was between eight and ten ruble. If there was about twenty ruble worth of material in a shop, the merchant was considered to be a wholesaler. Taxes did not bother the merchants and shopkeepers. They paid government tax (“promislovi nalog”; “guaranteed taxes”) of about 30 kopeks a year, according to the number of candles the women used to light and bless on Friday night. The taxes were not paid directly to the government, but to the collectors (“zborschtchik”), such as Reb Moti Waldman

[Column 614]

who would collect the leasing taxes from the government, collecting the debts with the help of other collectors, all of them our Jewish brothers.

The Russian authorities in the city were represented by few officials, the highest of which was the chief of police, along with his two helpers, inspectors, and 2…3 policemen (“desyatnikes”; “of ten men” sergeants), who maintained order. Among these, I remember the old policeman Kuzma.

This is how the local authorities were, and their relationship with the people was very good.

There was a prison in town called “dvoryanskaya turma” [“the nobleman's prison”], a large room where they detained criminal citizens by day, and then they went home at night to sleep in their own beds…

In the year 1880, the southwest train was already working, which at Radziwill cut across the Austrian border and from there went to Brody and beyond … to Lemberg. During the summer, in town, people rode in kibitka [Russian carriages] and in the winter … in peasant sleds.

The population in Dubno a hundred years ago, as the old people would recount, was … a small Jewish settlement. They would

[Column 615]

describe the place as “Dubno near Murawiez” in the 80s of the former century … about 5,000 souls, and they earned a living as shoemakers, smithies, harness makers, tailoring, carpentry, and masonry. As Jewish workers, there were chimneysweeps, limestone workers, dyers, folk doctors [barber surgeon], haircutters and shavers, and those who did drawing of blood, leeching and cupping. Jews also worked as furriers, porters, transporters, and watercarriers from the river. On the other hand, the peasants (“Poleshukes”; [Poleshchuki, is the name given to the people who populated the swamps of Polesia] in the area did the wood chopping, as they were “rented” by Jewish homes to chop wood for the winter. They would do this in the summertime and store the wood in the ovens by the houses.

There were no roads or sidewalks in town, so they put boards from one house to the next on rainy days. In the marketplace, in the center of town, was the City Council building, and in their yard was residents' garbage and waste. The city owned two mills. One … the watermill of Shloss (Shlossmill), and the other … of the Princess Szubalowa and her daughters. Jews earned a substantial living and comfort from both mills.

Once a year, there was a horse fair under the name of “Kontrakten.”

There were thick forests in the area, such as the Smyg, on the road to Kreminyc [Krzemieniec], and Jewish forest merchants of Dubno employed hunters, and they chopped down the pine trees, the oak trees, and the fir trees to export out of the country. At that time, Reb Aron Aronstajn was well known. He employed four hunters. His sons…in…law were Reb Nissel Wajnberg and Reb Shmuel Halevi Horowyc, descendants of the Shelah Hakadosh [Isaiah ben Abraham Horowitz, c. 1555[1][2] … March 24, 1630, also known as the Shelah Hakadosh, after the title of his best…known work; was a prominent rabbi and mystic].

The family Bratz (the son of Reb Tzadok) and the family Marszalkowyc belonged to the higher class of people in Dubno, who were blessed with wealth and fine character. The Bratz family was wealthy and they were generous spenders with an open

[Column 616]

hand. The largest textile business of in town belonged to them. They built up a beautiful kloiz for relatives and Torah scholars.

In the 80s, only traces of the Berlin Haskalah [Enlightenment] were still evident. But Chassidus also made roots in town, even though not everyone embraced it. In Dubno, there were shtiebelech [plural of shtiebel, small informal synagogue] of the Karliner and Ruzhiner chassidim, of the Ostrower, Olyker, Kotzker, Trisk…Stoliner, and Trisker, whose rabbis were descendants of Reb Motele Czernobyler [of the Czernobyler dynasty].

The Kotzker chassidim, loyal followers of the Rebbe [spiritual leader] Reb Mendele, were small in number. They followed their Rebbe, and studied Gemara [Talmud], Peirushim [rabbinic elucidations], and Tosafos [classic commentaries on the Talmud], prayed at later times, and did not travel to their Rebbe, but regularly sent monies [as a token, redemption] every year. The four main pillars of the Kozker chassidus in Dubno were: Reb Berish Shmarye's (Roitman) outstanding scholarship. His parents settled in Dubno at the beginning of the 18th century; Reb Beryl Yekhiel's, originally from Poland; Reb Leybish Teumim and Reb Berish Avigdor's, from the residents of Dubno.

There was no organized life in Dubno during that period. The city did not have a decent hospital, other than the “hekdesh” [disorderly designated area], and also did not have a place for care of the elderly. In the large synagogue, there was a small room that was called the “community room” in which two tax collectors sat, whose job was to collect money for the most urgent expenses, such as: for the baths, cemeteries, and so on. They also were busy with community issues. The Kazioner Rav was Reb Meyer Pessye's, who would write out birth and death certificates. Reb Pinkhas Pessye's, author of the book “The City of Dubno and Her Rabbis” was a grandson of Reb Meyer and earned a living as a shopkeeper. After Reb Meyer, the next Kazioner Rebbe was Reb Khaim Zalman Margolioz, and he also

[Column 617]

investigated the history of the city, even though he was not a native born Volyner, but came from Lithuania.

There were six shokhtim [ritual slaughterers] in town at that time. Among them were: Reb Meyer son of Yosef the shokhet and bodek [examiner of the meat] and a specialist at sharpening the knives; Reb Sender son of Lippe, an expert on sircha [any adhesions on the lungs which may render the meat non…kosher]; and Reb Yakov Shub, son of a simple harness maker, but a God…fearing man and a great Torah scholar, and of the Zinkower chassidim. The tax…farmer was Reb Borukh Cohen. The head of the Jewish court was Rev Dovid Tzvi Auerbakh, frail because of his old age.

Dubno had many houses of worship, kloizen [private study halls], and study halls.

The sexton in the large synagogue was the wealthy man Reb Meyer Szumski, an influential man appreciated by the aristocracy. Businessmen prayed there along with the ordinary people. This was a house with thick, tall walls, strong walls, and domed windows, and inside were wide, strong columns. Close to the synagogue, there was a small patch of earth, walled in, marking the bride and groom who were slaughtered under their canopy by Chmelnytsky's animals in the year 1648. The Holy Ark was a work of art made by wood carvers, and years later it was completely covered with pure gold. Precious curtain covers [of the Holy Ark], woven with gold and silver and handicraft, were often found in synagogues and on Simkhas Torah night [last day of Sukos holiday, celebrating with Torah scrolls], they put a white satin cover sewn with pearls over the Holy Ark.

Other than the large synagogue, there were kloizen of Trisk, Olyk, and Stolin chassidim, and also of the hat makers. Day and night, you could hear the voices of Reb Avrohom Mordekhai and of Reb Aron and the sons of great rabbis learning Torah and reciting prayers. There was no yeshiva [religious school] in Dubno, but there were many students of Talmud and small schools for young and old, with teachers for the very young. Whoever wanted to study Jewish law and Mishna [Talmud] … always studied in the Beis Medrash [Study Hall]. One warmly remembers

[Column 618]

the teachers of the young: Reb Fishel, Reb Yoel, and Reb Leizer Poliak; the teachers of Chumash [Five Books of Torah] and Rashi [primary commentary] … Reb Naftoli and Reb Leizer Berish'es; the Talmud teachers : Reb Itzik Leyb, the blind one Reb Avremele, and Reb Yosi Gutman.

In the Dubno region there used to be many trade fairs. On the 20th of every month there was a market day in Olyk; on the 15th of every month … in Mlinow; on the 10th … in Merwycz; and on the 20th … in Berestecko.

Traveling to these types of fairs was physically and mentally challenging. All of the roads were twisted, muddy, with ditches and hills. You would leave at dawn and get back in the middle of the night … everything for a livelihood.

Another source of livelihood for many families in town, left behind from the Polish rule, were the inns and temporary [“drop in”] houses.

In the 80s, in Dubno, there were a few leftovers of the Enlightenment generation, among them … Reb Avrohom…Ber Gotlober, the publisher of the magazine “Haboker Ohr” [“The Morning Light”]. There were no schools in Dubno at that time, therefore, when a Jew needed to write something in the province [government], or just to compile an address in Russian, he turned to Yossi the writer, who, with a professional handwriting, put everything on paper. Also, the young Pinkhasowyc knew how to put together requests with a nice Russian handwriting. There was one more like that in town, Khaim the writer, a man of the Enlightenment, who would always [write] satirically about the mud and dirt of the Jews that would always be removed on the eve of Passover. He used to say: “Wait, dear Jews! Wait! When the Messiah will arrive, all the holidays will be nullified, and then you will sink in dirt until over your heads, and all year round….”

In town, there was a whole institution by

[Column 619]

the name of “Potcht” [“mail”] … Leyb Silsker, with his horse and buggy. When letters were amassed, he took them from the town to the train station and from there … beyond…

In the year 1882, Dubno was boiling as a kettle: Czar Alexander III was coming to visit the town!

The homeowners took to beautifying their houses, they whitewashed the walls, cleaned up the garbage

[Column 620]

and washed the roads. The Czar really did come to town with great pomp, and with his successor Nikolai. Near Reb Avrohom's kloiz the community elders gathered, rabbis, and those who worked in the religious Jewish world, with decorated Torah scrolls in hand. But the Czar and his escorts only drove by the town and only visited the old castle. No one even glanced at the Jewish delegation…

Translated by Pamela Russ

In Dubno, which had three mainland entrances and exits, there were three suburbs: Surmicze, Zabramye, and Pantalye. In these suburbs, there lived primarily Ukrainians and a few Jews, but in the city proper, the majority of residents were Jewish. In general, the city of Dubno was a Jewish one. In the surrounding villages, the population was a mixture of several peoples: a large part was Ukrainian, Czech, and a few Germans and Poles. These Ukrainians always took part in all the pogroms, most of them against the Jews. The Jewish resistance was weak. Jews would hide in their houses and the Ukrainians would, undisturbed, do their work as part of the pogrom – murder and looting.

Between one pogrom and another, the Jews sat quietly in the town, li69ved with their worries about a livelihood, guarded all the mitzvos [religious commands from the Torah], and decrees and laws of the country. The majority earned their piece of bread in an honorable manner, and there were also many social statuses: the intelligentsia (intellectuals and academics), merchants, craftsmen, laborers, wagon–drivers, and porters.

The economic life in town was divided into a few sectors: industrial, handwork, laborers, those without income, and so on. In the trade sector, there were grain merchants, who bought wheat and corn from the farmers, and sold him the milled [ground products]: hops merchants who bought this item from the Czechs

[Column 620]

in the surrounding villages, dried and sorted it, in order to be able to sell it to the beer brewers in the country. A significant part of the material was also exported to Germany, Austria, suburbs, and so on.

Another section was comprised of shops, wholesale and retail merchants of food, clothing, manufactured items, confection, haberdashery, and so on. The majority of them earned a living from the non–Jewish population that used to come into town from the surrounding villages, would sell their agriculture products, and buy whatever they needed in the Jewish stores.

There were also the booth owners in the city market (toltczok) and around the market, they used to sell manufactured items, haberdashery, and food. The peasants would also bring their fare here and would sell them through arrangements with the market, or in the market directly.

Industry in the city was small and primitive. The main work was – with the hops projects. It was primarily women who worked there, but few were Jewish. Maybe ten percent. The workers there were specialists, the management, and supervisors – all Jews. The work was seasonal.

A significant portion of the Jewish population in town was employed in handwork. The vocations: tailoring, hat making, seamstresses, shoemakers, carpenters, smithies, wood turners, locksmiths. All of these

[Column 621]

activities employed workers, organized from the professional unions. A significant number belonged to the Communist party. The other salaried workers who were employed as trade employees, were not organized.

There was also a sector that lived from its own labor: wagon drivers, porters, [horse] cab drivers, water carriers, and water drivers. These worked hard in the summer and winter, but provided for their families in a most respectable manner.

The intelligentsia lived nicely and comfortably: doctors, engineers, lawyers, teachers, nurses, and others.

There were a number of season workers, such as those who were matzo bakers [for Passover]. The matzos, baked in Dubno, had a reputation because of their high quality and were sent to other cities in the country. The season of matzo export began right after Channuka and stretched until Purim. It was only after Purim that they started baking matzos for the local residents and for the others in the area.

Among the unemployed, there were Jewish youths who also did not have an opportunity for education. It was difficult to find work. Not all of them wanted to take on any type of job. A large portion was actually embarrassed to go to work, the majority – girls, and they became a burden to their impoverished parents.

Those who were poor and those completely without any means were not a small number in the city. They did not have enough bread to eat each day. Businessmen would borrow for them, and each week they would run around to collect some products and money for the needy families so that they would not be without challos [braided bread especially for Sabbath], bread, fish, and meat for Shabbos [Sabbath]; and for Passover, they should not be without matzo and other essential items. The businessmen also collected for the needy families for the other holidays. This work was conducted very discreetly, so that no one should know who were the needy ones.

As winter approached, a panic befell those families who did not have the means for daily life.

[Column 622]

The concerns to acquire the following were great:

All these districts lived their lives economically, each at his own level. Also, the synagogues, Batei Midrashim [Study Halls], shtiebelech [small, informal places of prayer], were divided into various categories. There were Study Halls for almost every vocation: tailors, shoemakers, hat makers, shoemakers, wagon drivers, and so on. There were also shuls [synagogues] and chassidic shtiebelech: Olik, Stolin, Bresslau, and Trisk [names of various chassidic groups]. Here there were people of all classes and districts. Each shtiebel and its chassidim [followers of that chassidic group] were loyal to each other in general and in their private lives, in joys and in pain, but during a Kiddush on Shabbos [festive event following morning Sabbath prayers], during Shalosh Seudos [the evening meal on Sabbath day], Melave Malka [festive meal following the end of Sabbath], on the Jewish holidays, and especially on Simchas Torah [last celebratory day of Sukkos holiday], everyone celebrated as one family – young and old. Also, the children and the youth that would come every Shabbos to the Beis Medrash, became connected through games (with nuts) during the pauses while reading the Torah, and other games around the Beis Medrash.

There were general synagogues in town that had no connection to workers, vocations, or living quarters. From these came the large shul which was attended by the lovers of cantors and choirs. The beadles of the large shul always tried to have a famous cantor, excellent director, and first–class choir. Because of that, they would come to the large shul from all districts and all corners of the city, just to hear the singing.

Education and Training

In the city, there was a whole collection of learning institutions, starting from cheder [very young boys], to Talmud Torah [older boys], teachers in the homes, yeshivos [religious schools for boys], government public schools (“powszekhne”), the Hebrew school “Tarbut,” the Polish–Jewish gymnasium [high school], and the Polish government gymnasium. At the beginning of 1920, there was also a Russian gymnasium and a Hebrew–Russian school.

[Column 623]

|

|

First article title: Real Work Is More Important than Politics Second article title: From Here and There (Reflections) Third article title: Report of the Activities of the Dubno Magistrate for the Year 1928 |

[Column 624]

Children aged four began their learning in the cheder. The children of the rabbis also went to school here until they began studying Gemara [Talmud], and then they went into higher level cheders, where they labored with Gemara and Tosefos [commentaries]. Some of these boys later studied in the yeshiva of Reb Avrom Mordkhe's school, founded by HaRav Gutman, of blessed memory. In this Talmud Torah, that had its own house, children studied free of charge. It was HaRav Rozenfeld, of blessed memory, the founder of the Talmud Torah, who supported them.

A large number of young girls and boys did not attend the government public schools (“powszekhne”), because the traditionally religious parents did not want to send their children to a school that had classes on Shabbos and on religious holidays.

The wealthier Jews sent their children to the Hebrew “Tarbut” school. Not everyone could afford to send their children there. So, some studied in the cheders, in yeshivas, and had private classes at home with a tutor. This was less expensive.

This system also existed for the private Jewish gymnasium, where the school fee was steep. Therefore, many youths, even capable ones, could not afford any form of education.

In the Polish government gymnasium they accepted hardly any Jews. In order to get in there, you needed exceptional skills, means, and connections. But even with all these in place, many Jewish students were refused simply because they were Jewish. The percentage of Jewish students there reached only 3%.

In spite of all these difficulties that I have described, the Jewish youth was not illiterate. A fine youth evolved, a Zionist youth, a party youth, a pioneering youth [for Israel], with ideals to achieve the Zionist dream and immigrate to the Land of Israel. Sadly, very few of them merited this.

Parties and Organizations

In the city, there were many parties and organizations, from the extreme right to the extreme left: Beitar, Gordonya, Tzeirei Mizrachi, Hachalutz, Hachalutz Hatzair, HaShomer Hatzair, general Zionists, “Bundists” and communists.

[Column 625]

Dubno between World Wars

The first Olim [immigrants to Israel] from Dubno who came to Israel at the beginning of the 1920s came from Hechalutz [Zionist youth movement in Eastern Europe]. In their club, there were lectures on cultural and educational themes about Israel. At the same time, they created the Hachshara, training program for Israel life. Other than these evenings where the lectures were given, the youth gathered together at the center for friendly get–togethers, discussions, talks about the situation in the Hachshara, and how life looked in the Land of Israel. Also, trips were organized to the Hachshara points and colonies. The Hechalutz was a very large movement.

In the Youth Hechalutz, which was under the direction of the Hechalutz, there was education for the youth up to eighteen years old. After that, they moved up to the Hechalutz. Young boys from all areas were members. This was a lively, energetic youth who wanted to work, learn, and preparing for Aliyah to Israel.

Gordinia [Zionist youth movement based on Aaron David Gordon] did not have a large number of members. They would assemble in a small center. But it was not dull there. Everything bubbled with life and efforts to fulfill the dream of A.D. Gordon – to make Aliyah and build the land of Israel.

The Shomer Hatzair [Guardians of the Youth] was a large, strong organization to which the “better” youth belonged, the majority gymnasium students, matriculated ones. In their club, there was multi–branched political, cultural, and educational work for the Hachshara and Aliyah. There was also a library with fine books – Hebrew and Yiddish. The youth was drawn there to enjoy the treasury of books.

Every summer the Shomer Hatzair organized colonies in a cultural and beautiful fashion.

In the Tzeirei Mizrachi, there were only a few tens of youths, without a fixed location. With time, they joined other youth organizations in town. It was A. Blass who directed the Tzeirei Mizrachi.

Beitar went on as a proper organization, because of their uniforms and slogans that said to conquer with gun and sword, the entire Israel, on both sides of the Jordan. They had small groups for the Hachshara and few of them went on Aliyah.

[Column 626]

|

|

| Top: list of family names and some sort of set of numbers to match 2nd from top: expenses – inventory 3rd from top – report of wood export 2nd from bottom –The Dubno Maggid, article in the “Dubno Life” [great Rabbi in Dubno, 1741–1804] Bottom: “Life in Dubno” – article |

[Columns 627-628]

|

|

| Page 627 – continuation of article: – “Life in Dubno” author's name L. Lerner Page 627–8 bottom article: “A Letter in the Report” editor's and publisher's signature on left, Yitzchok Sh. Rubenshtein Page 628 bottom, articles by Dawid Kagan, dentist |

[Column 629]

|

|

| The words on the banner say “Matura” [secondary school certificate] and “Prywat” [Private] on one side, “Gymnasium w Dubne” on the right. The inked date at the top is 1926. |

The general Zionists were active in the Zionist regions. Prominent businessmen of the city were connected to the Zionist movement, participated in the congresses in other countries, were active in Keren Kayemet and Keren Hayesod, and helped the poor Olim to fulfill their dream of immigrating to Israel.

In Dubno, there was also a large, beautiful sports club that included all the areas of Jewish youth “Hakoach” (formerly “Maccabi”). The majority of those who belonged to the club were the youth of various Zionist organizations. Other than the sports activities, Hakoach also had a first class wind orchestra, a good football team, and sections for other sports activities. The great hall in the center of the city attracted many

[Column 630]

adult and young lovers of sport. The events during the national holidays and the activities in the beautiful clothing, orderliness, and with the orchestra, evoked great enthusiasm from everyone.

All the organizations, even those with opposing principles, on the day of Lag be'Omer [33rd day of counting the Omer in the spring after Passover; celebratory event in memory of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai], were all united. Each movement, under its flag and banner, was present in the close by village of Palestinis, in order to celebrate this holiday, in the fields and forests.

When the “White Book” of the British Mandate was published, in which it locked the gates against Jewish Aliyah, all the above mentioned Zionist organizations protested as one – in the streets

[Columns 631-632]

|

|

|

|

[Columns 633-634]

|

|

|

|

[Column 625]

in their centers – against the proclamation, or against other anti–Jewish proclamations in Poland and around the world.

The city of Dubno, with its Jewish streets, synagogues, learning centers,

[Column 626]

parties, organizations , and institutions, with its lively Jewish life, – was erased in the years of the Second World War, all turned to dust.

|

|

Name of photographer on bottom of photo: Anshel Bitelman |

[Column 637]

by Binyamin Hoz and D. Karin

Translated by Pamela Russ

[ ] translator's comment

( ) remark in original text

1917. Giant Russia awakens. The dictator regime of the Czar is changed into a democratic system. The nation celebrates the liberation. The masses of Jews in Russia, particularly in the large centers, participate in the general euphoria. News comes from all sides that here and there the Zionist flag has been raised. Jews are presenting Israel as a salvation for their needs. Rumors of these events carry to Dubno, a typical Jewish town that did not follow the newer times. During that period in Dubno, there were no recognized Jewish organizations with independent activities. Some tens of respected Jews, who consider themselves Zionists, purchase the shekel [Israeli currency] and contribute to the national funds – but there was no real activity there.

The only light in those conditions is the Hebrew school, which thanks to the efforts of two elderly Zionists, was changed over into an important culture center. Tens of boys and girls study the Hebrew language there, also the history of the nation and its literature, and [develop a] love for the old-new Fatherland. All this continues, without stop, by the devoted teachers.

But the majority of the youth was busy studying a page of the Gemara [Talmud] or with worries of earning a livelihood. The new winds had not yet reached them. Only in the hearts of individuals was unrest brewing, we have to do something for Zion, but for now they do not connect themselves to any concrete task.

In the local Russian gymnasium [public school], that returned from its wartime migrations to the Kharkow region, there are some students with significant experience of Zionist activity. Slowly, a group of students in the Hebrew school befriends them. After several meetings, they decide to create a movement for Israel. A young group is set up, and takes upon itself the name “Hechalutz.”At the beginning, the group numbered 12-15 comrades [friends].

[Column 638]

Their first achievement – to prepare the candidates in practicality for their voluntary aliyah [move to Israel]. With the help of several old Zionists, a blacksmith's shop and a workshop for wagon repair, are created. It is from there that the settlers make their preparations, training themselves for physical work. In the evenings, they meet to talk about Israel and works of the National Fund. During the holidays, they organize for agricultural work with the farmers of the surrounding villages. All these tasks are not done in large numbers, since the number of comrades is small.

1920. The Polish Bolshevik war breaks out. Dubno is taken over by the Russians. Some of the comrades of the Hechalutz find work in the Soviet institutions and projects – and leave their organization, while the other section maintains the unity and collaborative work. With the recession of the Bolsheviks, part of the Hechalutz group goes along with them and remains in Kiev. Every single activity stops in the Hechalutz.

When the Polish-Russian agreement is signed, the comrades return from Kiev to Dubno and they renew their Hechalutz work. In the year 1921, anti-Jewish arrests begin in Israel, and aliyah goes on hold. Also, with the new Polish government there are now opportunities for work, but the Hechalutz falls apart because of the inactivity and the incapacity of the comrades to make aliyah.

For four of the devoted Chalutz comrades, who are devoted to the movement at all times, the idea is created of increasing the education work in the organization and to address the youth at a younger age. The question becomes: Should they organize a general youth organization Maccabi, or create a unit of Hashomer Hatzair, which already existed then in many cities of Poland and Galicia? Ambassadors are sent to the closest city of Lutzk, because there already

[Column 639]

was the Hashomer Hatzair. They return filled with ideas, and decide to create this organization in town.

In August 1921, the Hashomer Hatzair is officially established in Dubno. The four founders, thanks to their connection with the students of the Russian school, are successfully able to integrate tens of young boys and girls ages 13 to 17 into the organization. The first goal: to set up behind the town gymnastic and scout-type skills. The friends are divided into separate groups. Each leader directs one group. On designated days, when they are free of studies, they meet outside of the city or in a friend's house. There is no defined program, but they touch on various subjects, discuss actual themes, but the Israel problem dominates. Of course, they also talk about other social problems, and they set up activities for Keren Kayemet [Jewish National Fund]. The younger ones receive an education in the spirit of exploration.

Meanwhile, there is no connection to any specific center, there are no instructors nor directives from Warsaw. Thanks to the expanded activities, we also gain experience, work improves, and we set roots. The activities of the Keren Kayemet strengthen. The Zionist shekel spreads just as does the Zionist ideology.

The first Hebrew-Yiddish library, with a large reading room, is created in Dubno. Opening festivities take place as well as other events, all with their own efforts. These groups serve as propaganda for Zionist thought and to enlighten the Jews about Israel. If at the beginning parents were worried to have their children register in these organizations, thanks to the prolific activity of the Hashomer Hatzair, they become loyal members of the movement and help them as well.

Efforts are now being made to receive an official government permit to make all activities legal. The issue goes on and on. The local government begins to interfere. Once, during an expedition outside of the city, the police surround the “Shomrim” [members of Hashomer Hatzair] and with the help of the Polish patrols remove all evidence and disband all the participants. The madrichim [counselors] become upset at

[Column 640]

the government. One of the comrades takes the entire blame upon himself and he alone is taken to court. The others are freed but the police find only this one man guilty in organizing illegal youth activities and conducting communist activities. With great trepidation the Jewish populace follows the trial and the joy is great when the youth is given a clean slate of any of the guilt. The police, however, are still following the activities of the organization. They [the Hashomer Hatzair] are starting to look for new foremen for work.

The meetings are held in the homes of comrades, the culture-educational work becomes more intense. Efforts are made to legalize a local Tarbut [secular Hebrew-language school] society. After receiving a permit, the library and the reading room are given over to the new institution. Under the banner of the Tarbut, many events and activities take place.

1925. The organization stands on solid ground. New, younger energy evolves, those who are fit to participate. A connection is made with the central [office], instructors and lecturers often come from Warsaw.

With this first group of comrades, their idea was that the time had come to make their long-time dream happen – to move to the Land of Israel. They start to prepare the necessary paperwork. During the years of 1925-1926, the first group of madrichim leaves to Israel, except for Eliyahu Makharok, who died prematurely. He, who gave all his strengths to the movement, did not merit fulfilling his own dream.

After them, the steady flow of young pioneers from Dubno who wanted to move to Israel does not cease. Soon after its establishment, Hashomer Hatzair focuses all its work on the Land of Israel, and almost all of their comrades-new immigrants join the kibbutzim [pl. kibbutz].

The activities of Hashomer Hatzair continue to grow. They also accept children ages 8-10. Many of the non-partisan youth are influenced by the blessed work and also join Hashomer Hatzair or Hechalutz, which had renewed its activities. Hechalutz profits a lot from

[Column 641]

the help of Hashomer Hatzair but they go their own way and mainly work with the non-partisan youth. Also, from their league, tens of youths also make aliyah to Israel. Unfortunately, the opportunities for moving to Israel were limited, the number of certificates - very few.

1939. The outbreak of World War Two terminates the dreams and hopes of hundreds of youths who …

[Column 642]

want to build a new life in the old home. The members of Hashomer Hatzair and Hechalutz experience the tragic fate of Polish Jewry. Only a few individuals were successful in saving themselves as they fled to Russia or by joining the partisans. That year, a heroic chapter in history of the Dubno Jewish youth was severed.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubno, Ukraine

Dubno, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 Jan 2020 by JH