|

Translated by Pamela Russ

|

|

[Column 437]

|

||

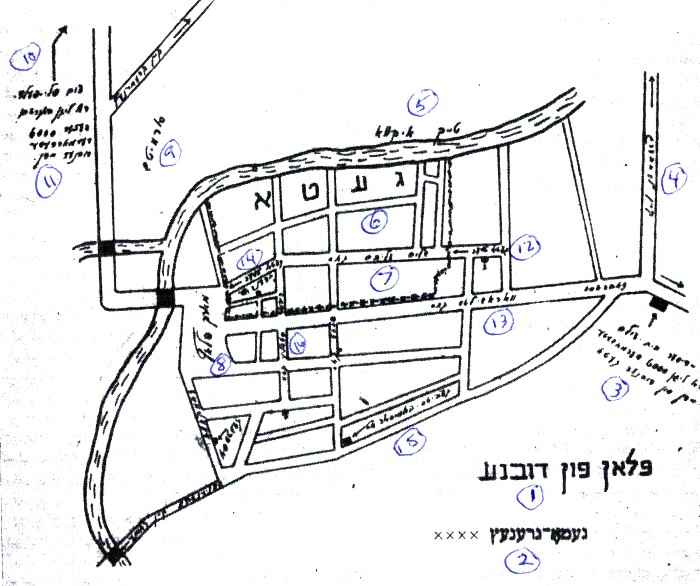

| Legend

Translated by Pamela Russ |

||

| 1 | Layout of Dubno | |

| 2 | Ghetto border | |

| 3 | Cemetery; here lie 6,000 dead from the Dubno ghetto | |

| 4 | To Lemberg | |

| 5 | Ikwa River | |

| 6 | Ghetto | |

| 7 | Shalom Aleichem Street | |

| 8 | Market place | |

| 9 | Surmicze | |

| 10 | To the airfield | |

| 11 | Here lie --- 6,000 people killed ---- | |

| 12 | Ghetto gate | |

| 13 | Wroclaw Street | |

| 14 | Ghetto gate | |

| 15 | Exchange Commissary Office | |

| 16 | Solomon Street | |

by Simcha Shtibel

Translated by Selwyn Rose

…and there was a river in Dubno and its name was Ikva.

This story about it is not because it belongs to the family of world famous and well–known perennial rivers – world atlases may not even record it; even the people of Dubno themselves, Jews and Christians alike, showed it little interest. Apart from a few Jewish families whose livelihood depended on fishing or the flour–mill whose wheel was driven by the river's flow – what was it to them?

|

|

And the Christians, on whom Nature had bestowed an abundance of her treasures including plenty of water, had no particular need of the Ikva.

Me? My eyes were not envious of them because of that. I felt no envy or jealousy for their “treasures” and their water, for what is the value of an abundance of water without the pleasures the water brings? For we – not they – have the prayer for “dew and rain” in our liturgy and we – not they – have the songs of our pioneers about water!

For them the Ikva is simply – a river. They exploit it as if it were nothing. And they have no affection or feeling for it. Only occasionally, on summer days the old grandmothers will visit it, their legs spread and bared to the knees, standing like storks in its shallow waters as they wash their dirty laundry, or in the autumn when the farmers' wives come to soak their sheaves of flax in the water; or during the off season when the field laborers come to harvest the reeds, dry them and weave them into all manner of baskets for sale.

The river was not even a topic of casual conversation. Only on rare occasions was it mentioned with anger because a victim drowned in its eddies, or if the town was under siege by an enemy and they were unable to cross its waters.

[Columns 447–448]

Only we, the children of Dubno loved the river and hugged it to us; for us it was – all year round – an inexhaustible source of joys, pleasures and enchantments.

And on that we will talk…

And when the time comes for the fierce battles between the stubborn winter, zealously guarding its domain, and the attacking spring, slowly sending its advance platoons of salvos of rays shot from the sun's arsenal, striking and tearing at the hair of the wonderful crystal–bearded winter; and the warming gale–force winds whirling relentlessly, tearing at the thick, pure white dressing of snow and leaving behind tattered and blackened drifts to cover it's nakedness – then it is the turn of the river. There is nothing like the importance of the battlefield between the winter and the spring…

With the coming of those early spring days no “hero” could control the impulse to fly to the suburb of Surmicze to get closer and feast his eyes on the perennial struggle, and there is no Hassid who would not rejoice at the disappearing winter that had prevented us, the children, the many pleasures of the river. During the long months winter had ruled with unbridled authority on our river. The glorious chamomile that grew along the banks and turned them green and the noisy frolicsome waves were conquered and covered by the relentless ice.

Indeed, we were ungrateful – we the children. We did not give the winter its rightful due from the not too distant past when that same ice–covered stream provided us with hours of healthy happy entertainment on it. Now with the warm spring breezes, completely forgotten were those time on its surface from our galloping dizzy hearts, skating on the ice of the broad stream, with the wind humming pleasant tunes in our ears and the sun's rays dancing on the surrounding snow–covered fields igniting them in a blaze of color. The game was exciting and a child whose parents were unable to provide him with skates never despaired – there was always a friend who would loan him his own or give up just one of his own for the sake of a friend so both of them could hold hands and skate together as one making both as happy as can be… breathing the cold, fresh air, rejoicing and flying… the sight was unforgettably exciting.

But with the coming of spring and the thaw, an abundance of water began to flow from the fields in strong currents from all directions as if rushing happily towards the battle, trying to find a way into the swelling river. Its wall, that was trying to remain stable, succeeded in the beginning in pushing the charge of bursting waves back with disdain but slowly cracks started to appear and the charging waves, with their incessant pounding on the wall created cracks and destabilized the foundations. Then chunks of the banks were ripped away and fell into the raging waters overcoming the defenses and forces of resistance chasing after the escaping clumps of ice, tossing them aside as if they were as light as feathers, crashing them one against the other, grinding them and turning their solid state into their original state – water. Then the waters spread, swallowing everything up, piece by piece over a limitless area as far as the eye could see…and then – not the sun's happy and dancing rays and not the clear blue skies, not even the happiness of the youthful, enthralled spectators could convince any one of us that Nature was able to quieten the turbulence of the river and its stormy waves. Indeed, the river Ikva showered upon us, the children during those first spring days an exciting spectacle for the eyes, a breath–taking experience. Nevertheless the joy of many of us was diminished and our hearts deeply touched at the sight of the distress caused to people living close to the river for the conquering floods didn't pass over their houses most of them trying to save the few possessions, leaving their homes with belongings festooned on their backs…

Nevertheless the Ikva will not bring peace of mind to the anger and disappointment of the children. Within a very few days the river began to rein in its turbulent waters and return to its normal course; its banks became green with reeds and rushes and its waters carried along fleets of flowers, water–lilies, white and yellow with long stalks like masts, and broad leaves – and all that in order to cause the children to forget their sadness over the misfortunes of our neighbors.

Those same days – the days of Counting the Omer between Pessah and Shavuot, we, the children were forbidden to bathe in the river and only the wayward and rebellious among us disobeyed the injunction. While the majority satisfied themselves with excursions along the river as far as the bridges that bordered the town, or stood and watched them and wonder at the beauty of Nature and listen…watching the sun slowly set, bestowing a rainbow of colors on the horizon, shade upon shade, listening to the frogs' and crickets' endless croaking and chirping. Thus would we stand and listen and dream sweet dreams of summer – together…

All summer long the river had no competitor for our attention. The festival of the First Fruits (Shavuot), that we celebrate albeit without first fruits, awakens within us the need to pluck reeds and rushes from the river banks to decorate our houses and courtyards, a ritual from days gone by. The reeds are moist and give off a heady strong fragrance, perfuming all the Jewish homes. And not only that! It had an excellent characteristic: you could hold it lightly between your lips and blow it like a trumpet!

And when Shavuot was over, the chains were released and we could bathe in the river freely. Then the children in their hundreds would gather congregate and go to swim in the river. And their equipment? What child today can imagine to himself? A couple of bladders acquired from a butcher and inflated…no used tires, no inflatables – all unobtainable then; all the cars

[Columns 449–450]

that were in town you could count on the fingers of one hand…and even if a child had no inflated bladder to hang on to, nothing would stop him from the daily hours–long pleasure swimming in the river. There were rowing–boats available and rowing in them was an added pleasure for us.

We compared ourselves to – and felt like – millionaires in our loyalty and devotion to the river, we, that same group of permanently idle lads, poor, short of nearly all material items, would come every day to the banks of the river to forget their worries and problems in their noisy enjoyment and sometimes even forget their hunger…

Thus the season would progress until the Feast of Tabernacles, coming to a close with the gathering of brushwood covering for our Succah (booth) and walking to the stream for the prayer of Tashlich[1]…

A farewell like autumn and autumn like a farewell…

Sunbeams still find their way through the gathering gray clouds covering the blue sky but their glitter gradually dims. The autumn leaves turn yellow and brown and the colors of Fall cover the ground. The pleasant days of summer still live in our memories but the inconveniences of winter are approaching and are noticeable in the homes where we now spend much time in the company of our parents…..

Rosh Hashanah. Crowds go down to the river – for Tashlich, where the last three verses of the book of Micah[2] are recited and they symbolically shake out their pockets and cast their sins into the deep and the children stand next to their parents and do likewise . There were many groups of Jews, dressed formally in their dark festival clothes …

And a choir of frogs serenades them with their croaking…

That was the river.

Thus we were our lives connected to us with our festivals, the winter days as well as the summer days, with our holy days and our prayers.

Thus it has been since time immemorial.

Until that same day… the Memorial Day for our grandfather and grandmother, uncle and aunt, cousins nephews and nieces – three thousand Jews of Dubno, men, women, babies…until that same day, when with the sunrise the river was used as a meeting place for Hitler's jackbooted blood–thirsty soldiers –

Until that same day the reeds and rushes of the river, that were always used to decorate our homes at festivals, were used as ambushes by wild beasts that fell upon our brethren and slaughtered them…and that same day as the sun began to set, the frogs of the river began their endless croaking for the children of Dubno who, for the time being at least, by a miracle have survived – Krah–krah–krah…

Evil, evil is the River Ikva!

Evil, evil, damned and evil!…

Translator's Footnotes

by Moshe Weisberg

Translated by Selwyn Rose

|

Like locusts from afar they came, Green devils borne on a wave, With helmeted heads, astride motor–bikes – With faces of evil, darkened with hate, Their cheering mouths noisily laughing, Blood and fire from their eyes flashed forth – One fire the world entire ignited And one bloody hangman came with.

A wild gang of hooligans rushed into town,

An elderly man bent over with age

And while Jews were marching along, |

| From the Polish by Y. Netaneli, July 1941. |

[Column 469 - Hebrew] [Column 711 - Yiddish]

by Yitzchak Fisher

Translated from the Hebrew[1] by Ilana Goldstein

Edited by Shirley Ginzburg

On June 22, 1941 the Germans invaded Russia. On that day German planes bombed our town: the first victim was a young 18 year old man from the Polishock family. His father stood and said: “My son, may you be the last Jewish victim of our town” and he didn't shed a tear.

The panic in the town was great and the children's cries were heart wrenching, a massive flight began: The Russian Army fled without stopping. Even 12–13 year olds were fleeing to Russia, and the Germans continued bombing…

My oldest daughter, Tzirl, and her husband Izzi Frishman, studied in an academic school in Kremenetz. My wife decided to help them escape to Russia. On Monday, the 25 of June, 1941, at ten o'clock (Y: in the morning) my wife rushed to the train station, but the trains had stopped running. She decided to go to Kremenetz by foot, a distance of 40 kilometers from Dubno. At that time, the Germans had invaded our town and my wife could not return to us. There was tremendous panic––anyone who went out into the street was shot on the spot. People started hiding. The wheels of the Howitzer–armored vehicles and the tanks were thundering.

I fled with my two children, Rochaleh, 13 years old and Shmulik, 10 years old, to the reeds on the banks of the river Ikva, because the Germans were bursting into the houses and beating the inhabitants with murderous force. For two days and a night we didn't eat or drink. On the third night as darkness descended I took the children home. Oy! Our house that we found was a disaster: The glass panes of the windows were smashed, the pillows and down blankets were torn and there were feathers everywhere. Whatever was possible to steal was stolen. We found shelter for the night at one of our neighbors. On the third day there was an all–clear (signal). We went out to the street and we found out that the Germans had rounded up 300 people and dragged them to the old castle, and there they were brutally beaten. Many died in the hands of the murderers. Eighty–five half–dead people were rescued.

On 2.8 (Y: 8th of February)[2], the Germans arrested the town Rabbi. He was dragged to the big jail and was never seen or heard from again.

On the 3.8 (Y:8th of March)[3] a decree was issued to select a Jewish council–“Judenrat”.

On Friday[4] toward evening the Germans made a blockade and caught 80 prominent citizens of our town. They dragged them to the old prison, beat them until they lost consciousness and took them out to the cemetery, and ordered them to dig a trench. They were agonizingly lowered in. For four days and four nights the earth was moving up and down on their grave.

On the 15.8 (Y: 8.15) villagers from outside gathered and came to town, and hunted the Jewish people and killed them in various ways. A total of 1,500 people died.

There was a “Judenrat” already in Dubno, but it did not lift a finger

[Column 470]

to help save the Jews: A rumor was spread that said, that it is possible to deliver packages to the already murdered for $10.00…

On 20.8 (Y: 8.20) the Jewish community decreed that everyone aged 16 to 50 must be registered to receive work permits–or else will die. There was a Jewish militia escorting the people to work and back. This continued during the whole winter of 1941–1942.

Passover eve 1942[5] a new decree: Ghetto! A Ghetto will be built!

I lived on Kantorska 39, and my relatives with me. I built six hiding places for a hundred people. In vain. We were driven out like cattle into the Ghetto surrounded by barbed wire. The Jewish militias did not spare us and beat us, and the Ukrainians and the Germans beat us as well. But being beaten by a fellow Jewish brother hurt more…

The “Judenrat” ordered us to bring 4 kilos of gold for the Ukrainian commander or else–– we will die. Each man brought his portion of gold. And again a new decree: Furs for men and furs for women to bring to the community or else… We all obeyed this decree as well.

One day my wife surprised us––she came to the Ghetto. Our happiness was immeasurable. After a few days my sister went out to the market to buy a few onions (one hour was designated for shopping for the Jews). A “miliziant” Fada Manishevitz approached her and hit her over the head with a club. She fell fainting. I went to complain to the head of the militia to complain about Manishevitz, but Manishevitz took out a knife and stabbed me in the rib. A man, Z.G. who stood on the sideline laughed: “No matter, a stab with a knife will not kill you…” For six weeks I lay hovering between life and death. Miraculously I survived.

And something new: the Ghetto was to be divided in two. Those destined to life and those to death. Those holding “work–cards” separately and the sheep for slaughter – separately.

One Thursday Yod Alef Sivan Tav Shin Bet––May 27, 1942 the Gestapo blockaded and slaughtered us. They murdered more than 3500 people (Y: a thousand people), among them my mother ( Y: Aleyha HaShalom, may her memory be a blessing), and our neighbor with her five children.

As darkness descended we fled toward the section of the “work–card” holders and we hid there for a few days. I found “protekzia” favoritism and we were registered amongst the living. Meanwhile the militia men were searching the clothes of the murdered and grabbed valuables and money.

Panic stricken, haunted by the sound of a falling leaf, we arrived at the New Year of תש”ג 1942.[6]

When I heard a new rumor: Graves were being dug for the remainder of the people…

[Column 471]

We decided to run away and hide with a Polish acquaintance. We stayed with him for a month (Y: ten days.) Then came the Gentile and said: “Fisher, do you have gold––good, if not you will have to scram from here…” I returned to the town, I dug and took out a few gold coins and gave them to him, and then afterwards he chased us away from his house. “Where should we go now?”

We fled to a nearby forest. I heard the sound of voices, I listened intently – I heard Jewish voices (Y: Yiddish spoken) We approached. And there was (a group of Jews) and a bunker…

We joined them. One day we saw a man, carrying a rifle, walking and coming near to us. It was the forester. “We must run,” I told the group, and that is what we did. We transferred to another location and dug in.

It was the beginning of Autumn, it became necessary to prepare a hiding place for the Winter. We went to scout the area, when we returned we saw a sight that made my skin crawl and my hair stand on edge: My wife and my son and with them women and children lay dead. I fell fainting to the ground. My daughter who was with me, remained alive. Eight men dug a grave and buried the dead. The day of the slaughter כ”ד כסלו תש”ג, 3 December 1942.[7]

Barefoot, hungry and wearing rags, we spent the nights in haystacks and during the days–– in the forest. We wondered those of us who remained alive, wondered why we survived? For what purpose? Is there any hope for us? We asked ourselves.

We ran out of food. It was necessary to get some bread. I went out by myself on a dark night. Where should I turn? I went towards the Czech village, Podaheitz. I collected some food in a bag. When I went out to the villages I armed myself with a heavy spiked club. As I left the village two loathsome youths pestered me, started to taunt me, and hit me. I feared for my life, but I did not lose my cool. I raised my club and hit one of them on the head and he fell to the ground. His friend turned to run. I kept my composure and ran after him, I caught up to him and with a heavy blow I split his head. I grabbed my bag and fled into the thickness of the forest. I sat down to rest. In the quiet of the forest I heard a slight whisper. I glued my ear to the ground–– yes someone crawling on all four was searching and whispering to himself: “I will still find him, I will find him”… I knew it was the second of the two youths. I took my life in my hands and ran towards him. I hit him with one blow and no more.

I searched through his belongings, I found personal documents and a long knife. I told the people what happened and we decided to abandon the forest. A rumor reached us that Jewish people of Dubno were hiding with a certain Polish man. We all transferred to him. The Polish man kept me in a haystack and there I slept for two whole days and nights. The sound of bursts of gunfire woke me.

The Ukrainians of Bandera[8], ambushed the Poles in order to kill them. The Polish man's wife informed us of the sad rumor. For the time being the Poles were saved.

[Column 472]

Close to this place there was a forest, and there lived a Goy (Y: Christian.) We fled there. I bought from the Goy, onions, bread, and cigarettes. The Goy would let us know periodically what is happening in the front and where the Russians are posted. His information cheered us up and strengthened our morale. One day we were informed that the Banderists were surrounding us. We got up and moved to another wooded area. It was bitterly cold, dark, and we were barefoot and naked, close to desperation.

We lay for many hours in a ditch that we dug under the snow, and again we moved to another forest. Suddenly we were frightened and alarmed we heard sighs and groans. We stared into the darkness. We saw: wild boars…

One morning we heard many marching steps: Poles fleeing…

There was an exchange of shots. We fled from there until we arrived at a fortified Polish post: Melisharna. The occupiers of the post were young, with a lot of arms.

Christmas of 1943[9] was approaching. The Polish group was celebrating according to their custom: They drank and became drunk, and didn't notice that they were surrounded by the Banderists and were taken captive, and we were amongst them…I was horrified to see the shocking scene: the robbers were poking the Poles' eyes out of their sockets, slicing off the women's breasts and hacking up men and women alive. We burst into a cellar full of big barrels and we lay there for three days and nights. After the Banderists left the killing field, we fled again to the old Goy, who entreated us to leave, as our end will be dire. From there we moved to a cellar of an abandoned house, but the cold and the frost were freezing us to death. At this point we were totally desperate. My daughter wanted to go to the town no matter what. But I knew that that would be the end. Again I went to a Goy and bought a loaf of bread weighing 2 kg.: We dug a hideout and lay in it for two weeks until the bread was consumed. We passed by again by the same Goy's house but as we approached I became suspicious: Why weren't the dogs barking? Why were the doors open? We stopped on the edge. We heard a voice ask: “Who is there?” I answered. The Goy descended. He brought a lamp, and we could see that the house was full of Russian soldiers! …

We remained for three days at the Goy's. Suddenly it occurred to me that we were still not in a safe place. My daughter and I went to the road, leading to Rovno. Russian soldiers loaded us onto their vehicles and brought us to Rovno. There were no Jews in the city.[10]

I went out to the road and any Jew that I met I sent to a fortified house which I chose to be in. A hundred and twenty Jews gathered. We did not reach peace.

The German bombardment was continuous day and night. After a while the bombing stopped. We headed toward Dubno to the killing field and the death train tracks. We saw the Goyim living and the Jews gone. I was fed up with the town. I took my daughter and we headed to Poland. (Y: I thought only: revenge, revenge to the Germans.)

Editor's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dubno, Ukraine

Dubno, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 2 Jun 2021 by LA