|

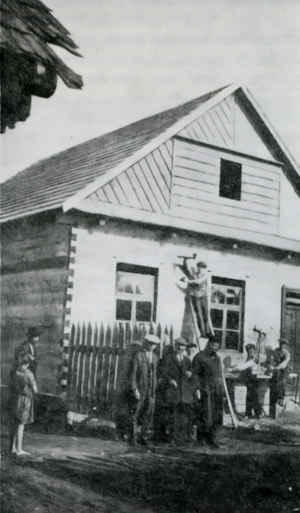

After the fire, the Bet Midrash is rebuilt[13]

|

|

[Page 165]

haRav[1] [the Rabbi] Bentzion

ben [son of] haRav Aryeh Leib Sternfeld[2]

by M. Alpert[3]

Translated by David Ziants

When I was a child I used to come to the home of the elderly Rav Sternfeld, Rav [Rabbi] Benda'at's father-in-law, and my visits to him became more frequent, because something attracted me to him and his leadership, and the recollections of these visits were engraved in my mind for many years.

I remember his radiant personality, which was all the fire of Torah [Jewish learning and practice] and much great wisdom. And most importantly, I remember his personality that commanded respect.

From abba [dad] z”l[4] I heard about his genius and his deep wisdom, and also, when I was a youth, I remember him as a man for whom the rabbanim [pl of rav] of the area would wake up early in the morning to go to his door and would receive his answers on matters of halacha [Jewish law], as a final decision [lit. full stop] that no one would dispute.

He was the only rav who served in the capacity of the district rav and all the rabbanim of the district were subordinate to him, not by virtue of dictatorship and force like happens with the gentiles, but by virtue of his personality, broad-mindedness and greatness in Torah.

I also remember that gentiles would listen to the words that came out of his mouth and were willing to submit to his decisions concerning disputes between themselves and the Jews of the area. There were gentiles who believed in his holiness and brought him gifts[5] in return for the advice he would give them and for the word of prophesy that seemed to be thrown from his mouth that would be fulfilled in them [the gentiles].[6]

These qualities led to the fact that the people spoke about him and how his deeds were bordering on the wonders performed by the Chassidic[7] rebbes[8] [rabbis], even though this town was known as being uncomfortable with “that cult”.[9] Thus a number of stories of wonders were told about him, and there were people who remembered a wonder or incident “as if it were their own experience” and would remember the period and the fact.

There is the story of a Jewish carpenter who, with his sense of commerce, decided to employ gentiles and to have them work on Shabbat.[10] The rav took the trouble on Shabbat and came to the carpenter to convince him not to continue violating the Shabbat, but the carpenter set his dogs on him and did not want to talk to him. Before he left, the rav still managed to tell him:

- You who set your dogs on me, so I will set your wife and sons on you. Before long, his wife separated from him and his sons left him. The carpenter remained forsaken and abandoned, and when he died, his death became known only three days after his soul departed.

But the most terrible story is the story with the owner of the soft drink store and this was his story:

When the first war [WWI] was still going on and the movement of soldiers continued and did not stop, a bar attender who was the owner of a soft drink store decided to open his shop on Shabbat, in order to win the soldiers' business. When the matter became known to the rav, he came to try and convince him to stop doing this, because the punishment for desecrating the Shabbat is great. The man did not heed him and ridiculed all his warnings concerning divine acts of punishment. When the rav came to him on the third Shabbat and he did not accept [the rebuke], the rav said to him:

[Page 166]

- There is also a punishment that is in this world [lit. on earth]You are an obstinate person [lit. ostrich] because you desecrated the Shabbat and you were warned and you continued to desecrate, so you will be taken to an unknown place shackled in handcuffs.

And so it happened. When the Germans came to the city that year, the man was taken away tied in chains and it remains unknown to this day to where he disappeared.

On one respectable and assertive gentile, I know that Rav Sternfeld's appearance had an influence on him beyond the realms of power and rulership. During my days, there was the incident when the Russian notary installed a telephone line to join his office to his home. Rav Sternfeld came to ask him to make the wires across the poles bypass the church, so that the city could also stretch the eruv[11] wires across the poles and save a lot of money that it did not have. The ruler[12] agreed on condition that he give him a photograph of his patriarchal appearance as a souvenir, but he did not have a photograph.

By chance, one photograph of the rav was found in the city, so it was given to the ruler and the non-Jew kept his promise. Many times he[13] was asked by the people of his religion what his purpose was [lit. he saw] in rerouting the telephone line and doubling the number of its lines [wires], thus doubling the expenses involved in having more poles, but he kept the explanation to himself.

I am reminded of an argument between him [Rav Sternfeld] and my abba, in which his sincere personality stood out just as abba's z”l status stood out. My abba was a veteran shamash[14] of his beit midrash,[15] and the rav used to accept his opinion on more than a few occasions. And here's the argument: In the old beit midrash there was a regular shiur [class] of the Talmud[16] circle headed by a great literate Jew and a very talented pedagogue named Zimmerman [or Tzimmerman]. This Zimmerman eventually immigrated to the United States[17] and the circle was left without a maggid shiur [class teacher]. Rav Sternfeld asked my father to propose to the circle, that they should accept his son-in-law [haRav Ben-Da'at] to teach the shiur. My late father z”l did not respond [in words], but his body language indicated refusal and he did not fulfill this request. When Rav Sternfeld asked him why he had not done as instructed, an argument started between them, and my father concluded by saying:

- Distinguished Rav, when R'[18] Zimmerman was the maggid shiur, the shiur was held in a fashion that participants and the teacher treated each as equals, and thus the listeners respected the set-up and persevered in Torah [Jewish learning] - but if Rav Benda'at were to take over, they would see themselves as if they were demoted to the rank of talmidim [students] sitting before their rav and the shiur would be canceled [disintegrate because no one would show up].

Rav Sternfeld understood what was hinted to him from the words of abba and thanked him with a friendly embrace for the honor he had found for himself and his son-in-law, and he did not continue insisting, but he knew that the listeners simply didn't want him.[19]

Rav Sternfeld published the name of his city in his book “Sha'aray Tzion”[20] [”Gates of Zion”], which at the time became a source of question-and-answer instruction for the rabbanim of the area and beyond. In the year 1929, a pamphlet from this work was published in Jerusalem, and generations later saw it as a source for our days as well.

It is also known that Rav Sternfeld's haskamma [approbation] appears[21] among the first[22] on the “Mishneh B'rura”[23] of the Chafetz Chaim,[24] ztz”l [pronounced Zatzal][25] – making his signature a signature to be honored.

R'[26] Benzion Sternfeld died in his beloved community of Bielsk at a ripe old age and with honor.

Zatzal [May a righteous person be remembered for a blessing].

Translator's footnotes:

Translated by David Ziants

It is not within the measure of our strength when writing [lit. telling] about the rabbis of Bielsk to write about the second rav [rabbi] of Bielsk, R' [Reb] Aryeh Leib Yellin, author of the extensive commentary on a number of m'sechtot [tractates] in sha”s [Talmud].[6] Firstly, because his tenure with us was two or three generations away from our predecessors, and there are few who remember details about his personality in general or his Bielsk personality in particular. Secondly, and this is the main thing, when we open the Vilna[7] Babylonian sha”s published by Romm Publishing House[8] and inside we find his commentary printed on full pages, alongside[9] the Maharsh”a, the Ma'har”am Schiff and the Ro”sh commentators,[10] we are overcome with an anxiety of holiness, and view ourselves as too small to cope with the measure of his greatness. So there was indeed a rav of Bielsk from those angels whose place of honor was preserved in the Hall[11] of the Talmud, set towards the inner sanctuary, right[12] next to Rash”i and the Tosefot [medieval commentators printed on the pages of the Talmud itself]. His commentary, which is a multi-dimensional book, is called “Yefeh 'Einayim” [lit. Beautiful Eyes] because it beautifies the eyes of man

|

|

After the fire, the Bet Midrash is rebuilt[13] |

[Page 168]

and it illuminates pathways for people in the sea of the Talmud.[14] But there was someone who said that the man stood out for his beauty and was known for his beautiful eyes, so he called his book by the name Beautiful Eyes to teach you that the beauty of the eyes is measured by the quality of their vision and the essence of their perception.[15] Thus he merited to be named after his composition,[16] and no one remembered his real name and would only refer to him by the name “The Yefeh 'Einayim.”[17]

In the introduction to his book on Massechet [Tractate] Shabbat [focused on the laws and practices of the Jewish Sabbath], the Yefeh 'Einayim complains that he is not able to live his life to the fullest, and that the community bothering him[18] and the matters of worldly issues of his city deprive him of time to devote himself to his life's work, which is commenting on the Talmud.

This complaint of haRav R' Aryeh Leib Yellin is based not only on however much time it took from him, but also that it took from him the prime quality of his free time, the quality of perfection required for this regard. Or, as he described himself, “… and I am like that amputated hand (stump), which presents a gift to the king from the wisdom of his palm,”[19] that is to say, whoever reads his commentary will have the feeling, as it were, of something incomplete, whose defect is the product of his lapse [lit. stump] in time, and if indeed it is possible to understand the unfortunate, through no fault of his own, author, then it will still be impossible to enjoy his work, because it is incomplete.

The above comes from the virtue of modesty that existed in him, and not from the virtue of the quality of the composition, or perhaps this testifies to his excessive demands on himself, because his composition was accepted as totally complete and it seems that he was the only and last member of his generation, this later generation, who was accepted into the lofty pantheon of Talmudic commentators.[20]

HaRav Aryeh Leib Yellin's period of activity began around 1853 and ended in 1867.[21] In this period the gates of the Talmud were closed to the commentators [the contents of the Vilna edition were frozen,] and for those who learn sha”s in depth, all future commentaries would need to be added as auxiliary pamphlets or small books, but not as an appendix within the printed volumes. As is well known, the Yefeh 'Einayim died young, and it can be assumed that the thread of his work was severed when he was at the peak of his ability, and the loss to those connected to the Talmud is incalculable.

About his death is told the fact, which is just about confirmed, that it was an accidental death caused by great mental anguish, which ended his life while he was still young.

This was during Russian rule in Bielsk. The city was small at the time, but central in her surrounding and her poor people were many. Wanting to make the giving of tzedakah [charity] as an obligatory and popular act that every person in the city could fulfill, this is what Rav Yellin did. He decided that it was possible to make do with p'rutot,[22] a small denomination of money equal to one tenth of a kopec, provided that the alms continued and became a day-to-day matter throughout Bielsk. A denomination worth a p'ruta [sing. of p'rutot] did not exist in Russian currency - that is, there was the ruble and the kopec, which is one hundredth of the ruble, but there was not a coin equal to one-tenth of the kopec which would be equivalent to a p'ruta. So he took the initiative and “printed” p'rutot of his own. As it is told, he was also famous for his beautiful handwriting, and in his handwriting he used calligraphy and drew notes with the worth of p'rutot, and every shopkeeper would accept these notes as “legal tender,” because they knew that the backer was the Yefeh 'Einayim. These notes, which were given to the poor of Bielsk, were also distributed to the poor of nearby Kalashchalsk, and it was found that one of them, or someone else in Kalashchalsk, “forged” Rav Yellin's private money. When the notes multiplied and reached an astronomical sum of

[Page 169]

900 rubles, a sum he was unable to pay, he became very weak in his mind and his heart ached that through his pen, the Jews failed, and gave their goods on an illegitimate fund.[23] His grief grew day by day with the proliferation of p'ruta notes and he fell ill. Within a few days he passed away.

With his departure, a figure who came out of the rabbinical world only at the beginning of his flowering, left us. And who knows what was lost to Judaism at that time, whose whole confidence was in the walls of the Torah and its flagship personalities, who became the educational legends that inspired greatness and faith within the people.

From the elders of Bielsk I heard two things, connected to his name, that testify to his great wisdom and sense of righteousness and justice for orphans and widows.

There is the story of a widowed woman who provides for her orphans by working as a baker in a bakery she operated in the rented house of a rich man in the city of that time. One time, the man wanted to remove the widow from his house. He told her that he wanted to renovate the house and that she had to leave for a short time until the renovation was finished. The widow left, because she believed the man, but afterwards he did not let her return to her bakery, and the widow was condemned to starvation along with her orphans. HaRav Yellin asked the rich man why he wouldn't allow her to return to the place of her livelihood, to which the man replied that he needs the house for himself. And no one will motivate him to give it up. The rav's attempt to convince him did not help and the man stood his ground. He said he needs the house for himself and someone close to him, etc. Here Rav Yellin did not hold back and said to him:

– And how do you know that you will enter this house and that you will enjoy [or benefit from] it?

|

|

[Page 170]

And it happened that when the renovation was completed and the rich man was about to enter to live there the next day, he suddenly saw and behold, one of the fingerboards [also known as a roofing shingle] on his roof was not attached straight, so he went up to the roof to check it. The fingerboard broke and he fell, with his head hanging between the roof beams. Unable to free himself from them, he choked.

So the story ends, and the result is known: The house was returned to the widow and Bielsk knew that there is a judge of widows in the place and one should not act harshly against them, and they are not to be mistreated [lit. their blood is not free-for-all].

The second story relates that Rav Yellin, who was called to different cities for consultations and to give rulings in Jewish law, would appoint two[24] or three Torah scholars[25] from the local people, who would take his place during his absence. One day, a woman came to the house of the rav when he was absent and brought her questions before the bet din [court][26] that stood in for the Yefeh 'Einayim. She told them that when she brought a slaughtered female goose home and began to prepare it[27] and kosher[28] it, she could not find the bird's ovary and one should not cook a female goose with her ovary,[29] as is well known.[30] What do we do?

The three sat and embraced their thoughts and memories, where they would find an answer to this case.

And they didn't find it and the embarrassment was great. When they despaired and their hearts ached for the loss[31] that would be caused to the woman, the door opened and Rav Yellin returned from his journey. When he heard their petitions, he turned to the woman and told her to please go home and check that maybe it was not a goose but a gander [male goose], and as is well known, it is impossible to find an ovary in a male.

The woman came back and indeed the bird was a gander.

Bielsk was hailed for having this great rabbi, a world prodigy [Heb. Gaon].[32]] No one thought of suspecting him of greed, just because he had indeed made a mistake [lit. failed] regarding his p'ruta notes, and the bet midrash hagadol [the great synagogue] that was established in the city after his death was named after him. And for many years his name was remembered among the people there gloriously.

The Yefeh 'Einayim added a crown of honor to Bielsk, and in memory of the honor that he bestowed, we will also remember the Rav R' Aryeh Leib Yellin for a blessing.

Translator's footnotes:

Translated by David Ziants

When Rav Bentzion Sternfeld decided to marry off his only daughter,[2] he went to the yeshivot [colleges of Talmudic learning] to try and find a groom for her who could also take his place as the city's rav after he passes away [lit when his day will come]. He was looking for a groom who would have Torah [Jewish knowledge and learning], wisdom and good manners bound together, so as not to embarrass the rabbinical seat of Bielsk and to give the community of Bielsk a rav it deserved.

This is how he brought to the community the Rav R' Moshe Aharon Benda'at and the Jews rested the decision in the hands of their beloved rav [Sternfeld], whose choice must certainly be the correct choice.

In 1917, the old rav passed away and the new rav of Bielsk[3] was elected. A few years before his father-in-law's death, haRav, R' Moshe Aharon would help him lead the community and serve him in all rabbinical matters. Thus for many years he merited to be tested in various situations by different people of his community, until he was accepted by them.

The city loved him, although he was always remembered, and not to his benefit, for being “the rav's aide.”

He was upright, good-looking, tall and with a face that demands respect.

[Page 171]

According to his ancestral tree, he was from a long line of rabbanim,[4] a descendent of rabbanim and prodigies, whose sons were all rabbanim and teachers within Israel [the Jewish People]. His brother, haRav Bangis of Bodki [Bocki] and Kalvari, immigrated to the Land [of Israel] in the 1920s, settled in Jerusalem and served for a long time as the chief rabbi of the ultra-Orthodox community.

HaRav Benda'at was not one of the fiery orators,[5] but as he was a Talmid Chacham [learned Torah scholar] and had pleasant manners, his words were accepted willingly and obeyed.

Most of his fame came to him in the city because he feared G-d and believed to the depths of his heart. His innocence in many cases led him to rise above the clouds of reality, with all his ammunition for the sake of the sanctification of the name of heaven [Heb. shem shammayim, i.e., the name of G-d], and his rising like this serves his innocence and his perfection of faith.[6]

During the first German occupation in 1917-1961 [a typo, the actual years were 1915 – 1919] the first community council was established in our city. General Zionists, religious,[7] Tzeirei Tzion [Young Zion] and Poalei Tzion [Workers of Zion] participated in the elections, as well as the Bund [socialist movement who were not Zionists and not religious]. At the festive opening meeting, representatives of the political parties stood up to make their first statements, in which each one detailed his “ani ma'amin”[8] [credo]. When it was the turn of the man representing the Bund to present his words and Rav Benda'at presided, everyone was instructed to listen not so much to what the man, who was known as an apostate and abandoner of religion, would say, but also to “see” how he would present his declaration in the sense of “how the penny will drop” [lit “how the matter would fall.”] And the penny did drop. The Bund representative declared that whatever he will do as part of the committee would be in order to be loyal to whom he represents and to his conscience whatever that will be, and this is to fight the religion of Israel [i.e. the religion of the Jewish People] and the dweller in heaven.

|

|

Standing: [15] S. [Shepsl] Eisenberg,[16] M. Jungerman[17] |

[Page 172]

When this statement fell, haRav Benda'at stood up and made a k'riah [a ritual rip] to his clothes, expressing his mourning[18] for a soul from Israel that had wandered away. This made an indelible impression and the social reactions to the rav [who publicly demonstrated his principle] of faith exceeded the boundaries of logic and scrutiny [i.e., the reactions were extreme]. Since then, the Bund man has been an outcast and was belittled among the people of Bielsk, and his entire status was undermined.

HaRav Benda'at nurtured the religious educational institutions in Bielsk, took care of the budgets for their upkeep, and in this concern he was tireless. The exchange of letters he had with our relief in America [the JDC (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee), United Bielsker Relief, and individual families provided aid], and some remnant of which stayed with us here, testifies to how great his devotion to Torah and Talmud was. He also worked hard to maintain the standard of study in the yeshiva[19] and Talmud Torah of Bielsk. He would conduct frequent exams among the students and devote many hours to this.

HaRav Benda'at did not come up with chiddushei Torah [innovations in Torah learning] or make fiery speeches, but he guided the people of his community in the ways of Torah with devotion of innocence and humility and took care of its welfare according to his way. And when the day of the bitter Sho'ah [Holocaust] came, when the Nazis sent the Jews of Bielsk to the Bialystok ghetto to transfer them to the Birkenau[20] crematoria, the Nazis suggested to him to remain in the city, but haRav Benda'at refused and chose for himself to join the people of the Bielsk community to which he tied the fate of his life.

For twenty-five years, haRav Benda'at herded the people of the Jewish community of Bielsk and had the most tragic privilege of being the last of its rabbis.

Zecher tzadik liv'racha! [Remembering a righteous man for a blessing!]

Translator's footnotes:

Translated by David Ziants

R' Yechezkel Levintal was known in our city not as a rav and a rabbi who can make decisions in Jewish law for the community,[2] but simply as “the Dayan” [”the judge”]. R' Yechezkel fulfilled his role as dayan during Rav Benda'at's tenure and was as if he were subordinate to him. But the people of the city knew that this was not the case, not that he was any less valuable than Rav Benda'at and not that he cared about being his subordinate.

Apart from his role as dayan and substitute rav, R' Yechezkel was the director of the talmud torah [religious instruction elementary school] in Bielsk and raised many students who respected and appreciated his Torah personality and blessed virtues.

HaRav Levintal was known for his great knowledge, and there were those who said that his learning was greater than their learning and his proficiency was more extensive than their knowledge. R' Yechezkel was a simple Jew who made a living from a small shop, and his wife took responsibility for the finances, and he sat all his days, every day wrapped in his tallit [prayer shawl] and tephillin [phylacteries][3] studying, reading, learning and praying. Bielsk took pride in him for the perfection of his faith and his mystical personality. His persistence in learning and abstinence from the affairs of this world, including community and public affairs, made him a living legend and a symbol and hallmark of Bielsk. Out of the admiration and affection of those complete in their faith[4] of Bielsk, they took the trouble to install a small shady pavilion made of ivy for him, altana [gazebo] in another language [Polish],[5] within the tree garden next to the bet midrash of Yefeh 'Einayim,[6] so that in the summer he could go outside of the bet midrash to sit in the air of the gazebo, continue studying, and fill his lungs with fresh air.

[Page 173]

They also honored him with special respect and would come to his home on Simchat Torah[7] to make him happy and rejoice in his Torah.

In the 1930s he immigrated to the Land [of Israel] with his second wife and daughter, in order to settle down in holy Jerusalem, which is very holy[8] to him. Here, he was readily accepted by the ultra-Orthodox community,[9] and he served as head[10] of a yeshiva and teacher[11] in a talmud torah.

After a few years, he fell ill and was advised to travel to Vienna to be cured. When he arrived at Haifa port to sail, he found that he missed his ship by only a few minutes. This served as a sign to him that his trip to Vienna was not desirable in the eyes of the holy one blessed be he,[12] and he no longer wanted to leave for Vienna.

He died in his city, Jerusalem, as a result of his illness.

May his memory be blessed with us.

Translator's Endnotes:

Translator's footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Jul 2025 by LA