by Richard L. Baum

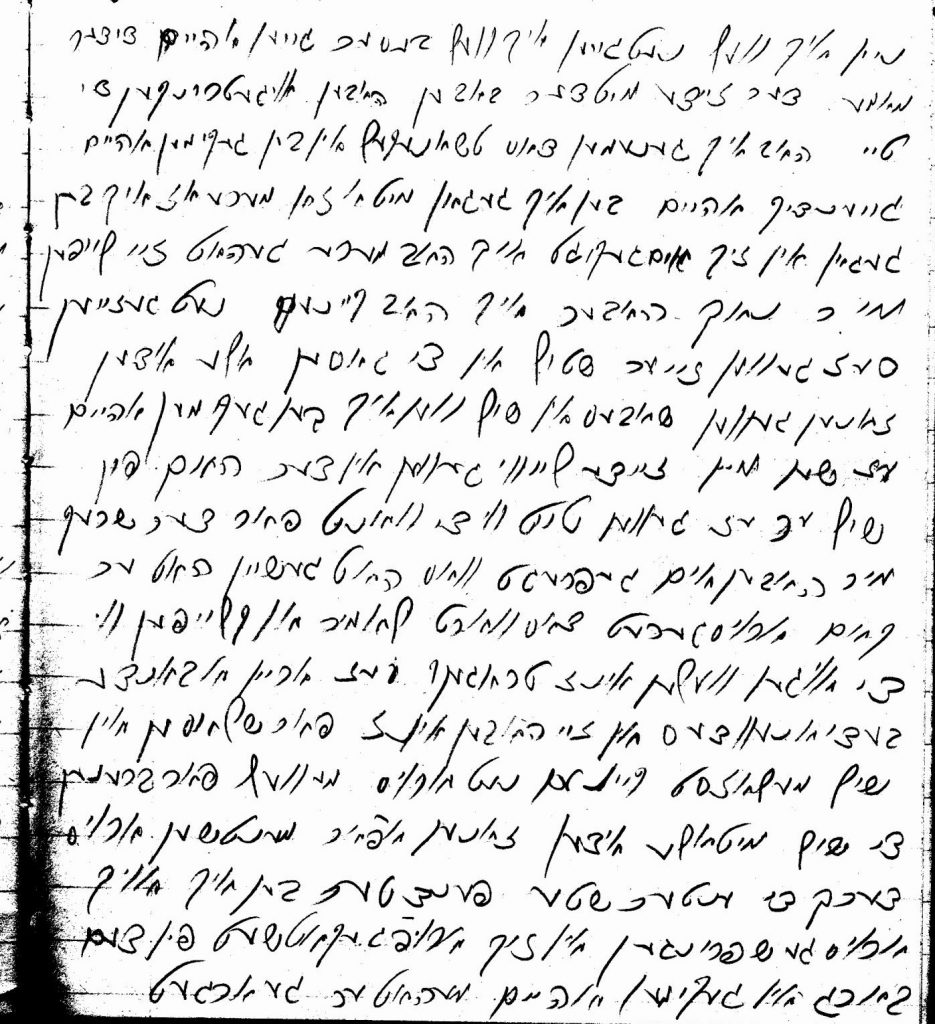

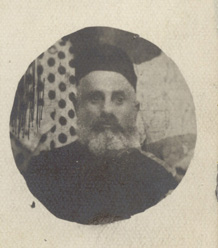

After my mother (pictured above) passed away in 1999, at the age of eighty-eight, my sisters and I were left with the painful task of removing nine decades of our parents’ life accumulations from their Bronx apartment. Hidden among the expected detritus was the surprising discovery of several handwritten notebooks and letters written in Yiddish and in Russian. A cursory glance told me that these belonged to my mother, as her name was inscribed within the notebooks. The quality of the notebook paper, together with the few recorded dates, made it clear that they were written in the 1920’s in Russia, where my mother was born and where she spent her first seventeen years.

I had no clear idea what these notebooks contained; some of the text appeared to be poetry. It was possible that I was looking at a personal diary, and I had some unease about intruding into my mother’s private thoughts. I put the notebooks aside with the intention of, someday, having them reviewed by a Yiddish speaker to determine the nature of the text. If there was anything of genealogical value, I would have the complete text translated into English. Years passed, during which time I concentrated on developing other source material relevant to my family history research. In 2004, this effort culminated in my publishing a two-hundred-year history of the Baum and Sevransky families.

It was not until 2009 that I re-discovered my mother’s notebooks and letters; they were sitting demurely in the back of a desk drawer. It was time to have these documents translated. Maybe I would gain a clearer view of my mother’s life in her native village of Tarashcha, Ukraine, located one-hundred kilometers south of Kiev. I already knew that my mother, then known as Sima, (a.k.a., Selka), her five siblings, and her mother Pessie lived in this village during the Great War (my mother’s father, Volf, was killed during this war); that during the German occupation of the Ukraine German troops were billeted in her house; and that she and her family suffered pogroms and the chaos and fear of the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Civil War of 1918 – 1921.

The translation of the notebooks did, indeed, provide details of life in Tarashcha during this period. My mother wrote, in Yiddish, a surprisingly gripping memoir of a pogrom, and of her family’s later attempt to immigrate to America. The remainder of the material, except for a few letters, turned out to be in the nature of a “farewell” album of poems and songs written by my mother’s friends and relatives as my mother and her family finally left for Die Goldene Medina. I published my mother’s memoir, together with a selection of letters, poems, and songs, in Writings From Tarashcha, 1914 – 1937, by Selka Sevransky Baum.

My mother’s description of life in Tarashcha during this difficult period includes the following:

“There was a revolution and all kinds of soldiers began to come in, and there were bandits. They began to kill Jews and to take whatever they had. They beat them until they killed them. They were taking revenge as if they were apostates!”

The Jews of Tarashcha, my mother states, established a self-defense force, though Tarashcha’s force was only effective within the town; once a Jew left the town, and was traveling along the roads, which was essential to earn a living, that Jew was at grave risk of being robbed and murdered by bandits and partisan units who prowled the roads.

“The people could no longer stand what was being done to them, so the people decided to defend themselves. They got a few rifles and they went around the streets [to make sure] that there was no more killing. It was quiet in the village for a few months, but people could not sit in their houses anymore. They had to travel to markets to earn [money] for food and to live on, so the killing began again.

As soon as they saw a Jew, the bandits came out of the woods and took the money that they [the Jews] had earned, then they killed him [sic]…

The people who had the few rifles could not watch everything and prevent this, because the bandits were like dogs, and there were only twenty people watching [out for the Jews]. This is how we lived: frightened and fearful.“

An incident that was specific to my mother’s family involved her maternal grandfather Levy.

“…Grandfather Levy was already home from the synagogue. He was white as a sheet from fear. We asked him what had happened and he was barely able to speak. He said, ‘… A gang of bandits came and locked us in the synagogue. They were not letting anyone out. They wanted to burn down the synagogue with everyone in it. A few people climbed out of a back window, so I also jumped out and rolled down the hill and came home. They killed Zavel the butcher and Zavel the carpenter. They were brothers-in-law. They slaughtered everyone on the street.’

…near the pharmacy all the soldiers are standing around playing music and all the people had gotten dressed up to go see them play music…

…They had tricked everyone into coming outside. They had dressed up in nice clothes and had gone to hear them play music. Then they killed all the people. They fell like straw! …“

When I first read my mother’s memoir, I wondered how accurate she was in relating these events and in quoting her grandfather’s account of what happened to him. After all, at the time, my mother was fairly young, not even a teenager, and these experiences had to have been traumatic for her. I had no way to confirm what she had written or omitted. My mother’s paternal grandfather Isaac may have been murdered during this same 1919 pogrom (I only heard of this from a second cousin; my mother vehemently denied that her grandfather Isaac had been murdered).

Some years after the memoir was published, I had gotten access to an official list of Tarashcha pogrom victims (robbed, beaten, and murdered) that had been compiled soon after the 1919 pogroms. A copy of this list, written in Russian, was purchased from the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP). I hired a translator to render the Russian into English. My aim, as a family historian, was to locate the names of members of my family that might be on the list. I was not disappointed; the list was rich in names, demographic data, and causes of death. It appeared as if the rioters’ rampage did not miss any Jew living in Tarashcha! My mother and her immediate family were recorded on the list; so were other Sevransky family members (including my mother’s grandfather Isaac, who was listed without any indication of injury or death), as well as other families that were connected by marriage to the Sevransky (Savransky) family.

Something unexpected occurred as I perused the victim list. As my eye scanned down a page, and continued on to the following pages, I suddenly “froze”. I had a nagging feeling that there was a name on the list, neither a Sevransky nor a surname connected to the Sevransky family, that I had seen before. So, I went back, looking for that name. I paused at the name of Zayvel Litvinovsky, a Jew who had been killed by a bullet during the 1919 pogrom; Zayvel was a butcher. Where did I see that name before?

As I was mulling over Zayvel Litvinovsky’s entry, I noticed another entry on that same page – Zayvel Volkov Pekir, a carpenter who had been killed by a sword. Then, after a while, enlightenment! An “Aha” moment; I made the connection! In my mother’s memoir, she records her grandfather Levy’s description of the murder of the brothers-in-law, Zayvel, the butcher, and Zayvel, the carpenter! And here were two “Zayvels”, with the same occupations, recorded in the official 1919 victims’ list. To my great satisfaction, my mother’s description of the pogrom was, indeed, accurate.

January 2020

New York, New York, USA

[A slightly different version of this article first appeared in AVOTAYNU The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, Vol. XXXIII, no. 4, Winter 2017. It is reprinted with the permission of AVOTAYNU.]

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

The translation of his mother’s handwritten notebooks yielded detailed information for Richard Baum about his mother’s life in Tarashcha, Ukraine, including the 1919 pogroms. Richard published her work in Writings From Tarashcha, 1914 – 1937, by Selka Sevransky Baum. Click here to learn more about this memoir.

Richard found the list of Tarashcha pogrom victims on the website of the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP).

For more information about Tarashcha, see the Tarashcha Town Page on JewishGen’s Ukraine SIG Webpage and JewishGen’s Tarashcha KehilaLinks webpage.

[Note: Both of these pages were created by Richard Baum.]