by Helene Schwartz Kenvin

Being a kohain, a descendant of the priests of ancient Israel, may be a source of pride. On the other hand, having a great-great-grandfather named Abraham Cohen can result in genealogical tension-headaches. City directories list Cohens by the hundreds and Abraham Cohens by the dozens. Soundex entries compound the Cohen-research-problem with spelling variations such as Cohn, Cohan, Kohn, Kahn, and Kahan — to say nothing of the permutations introduced when Abraham becomes Avraham, Avrum, Abram, or Abe.

I often have expressed my wish that our family surname had been Hirschenfang, Pretzelfutser, or something equally exotic, because Cohen is so common a surname that it is a nightmare to research. Our family’s first names make the research even more difficult. Abraham Cohen is the Jewish equivalent of John Smith. Looking up the next generation — Harris, Louis, Jacob, or Israel Cohen — can lead to dozens of listings. Finding documents for Abraham’s son Alexander Cohen (my great-grandfather) is a bit easier, but not much. When confronted by so many entries with the same names, how is it possible to determine which ones pertain to our family?

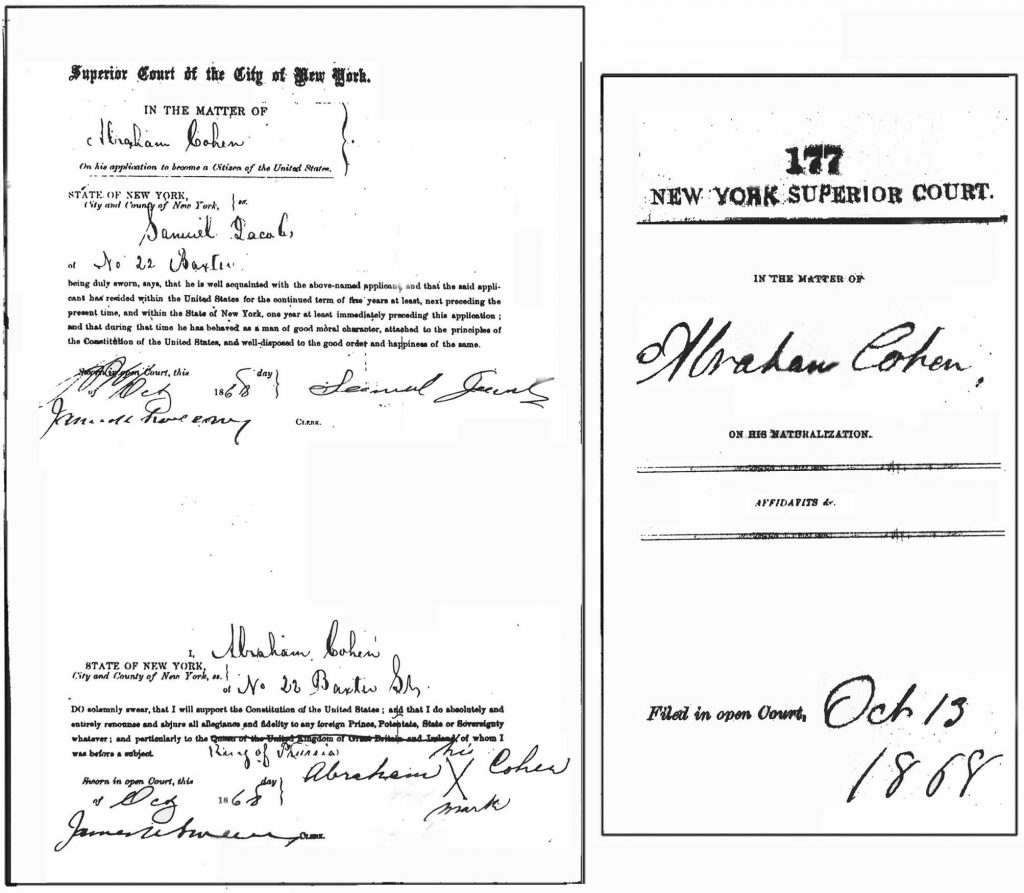

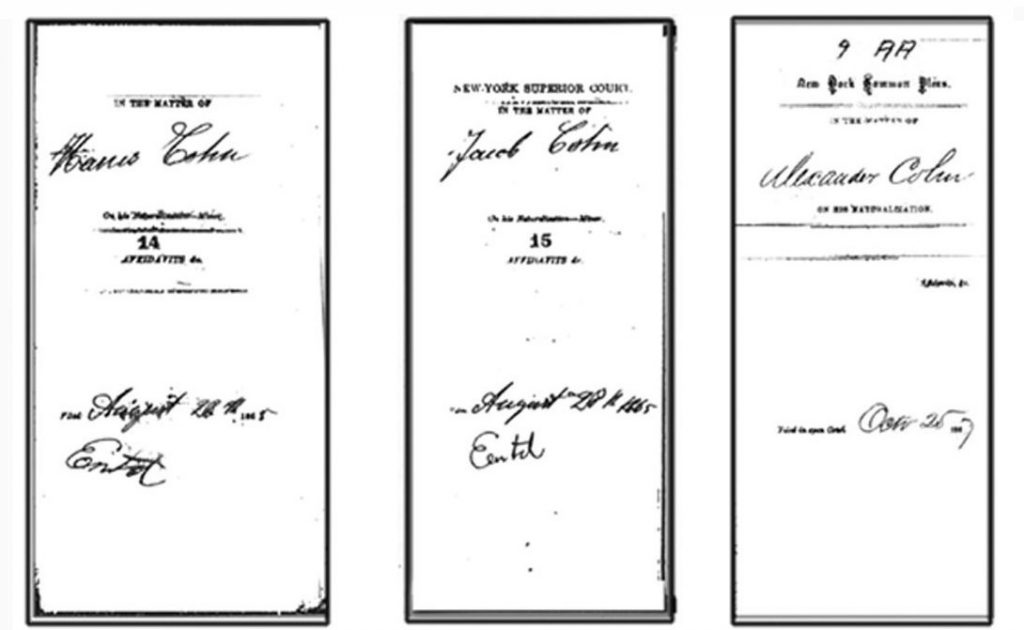

Amidst a sea of Cohens in the indices to U.S. naturalizations that took place in mid-19th-century New York courts, I am certain that I have found the documents relating to my ancestor Abraham, his sons Alexander and Harris, and his son-in-law Jacob (his daughter Dora’s husband). I found Alexander’s and Abraham’s documents in the late 1970s and Harris and Jacob’s papers in 1998. How can I be so sure that these actually are my family’s papers?

First: According to the documents, all four of these men lived on Baxter Street in Manhattan, which I know to be where our family resided and where many of the multitude of first cousins they produced were born. Second: My Cohens were from Prussia and all four of these men renounced their allegiance to the King of Prussia. Third: Harris and Jacob apparently went together to be naturalized on August 28, 1865, as their documents were filed on that date and stamped with consecutive filing numbers 14 (Harris) and 15 (Jacob).

The final piece of evidence was the most compelling. All four of these documents confirming U.S. citizenship were witnessed by Samuel Jacobs of Baxter Street. The surname Jacobs already had appeared in my research of the family of my great-grandmother Yetta Rotholz (Mrs. Alexander Cohen). I had reason to believe that her sister Ernestine (Aunt Steena) Rotholz had married a man named Jacobs. Older Cohen relatives in the Alexander branch had talked about a first cousin named

Charlie Jacobs, who had a clothing store in Albany and whom they thought was their Aunt Steena’s son. As soon as I saw the name Samuel Jacobs on each set of the naturalization documents, I suspected that he might be Alexander Cohen’s brother-in-law.

Seven years after I found the last two of the four documents, my hunch was proven to be correct. Some years before, I had listed the Jacobs surname in the Family Finder on the Jewishgen website. In 2003, I was contacted by a man named Burt Heisman from Albany. He said that his mother was the daughter of Alexander Jacobs (Samuel’s son, but Burt did not know that) and that his grandfather Alexander Jacobs had a brother named Charles Jacobs.

At my request, Burt took a photograph of Charlie’s grave in Troy, New York, and sent it to me. Burt did not read Hebrew, so when I translated the text on the gravestone, he was delighted (as I was!) to hear that Charlie’s Hebrew name was Tsadeek ben Shmuel (Samuel) Eliezer.

Burt had no idea what his great-grandmother’s name was. I asked him to get a copy of Charlie’s death certificate. When it arrived, we learned that Charlie’s father’s name was listed as “Unknown Jacobs” (but we already knew from Charlie’s gravestone that his father’s first name was Samuel) and that his mother’s name was “Ernestine [maiden name] Unknown” (I knew that it was Rotholz).

Equally thrilling was that I had a photograph of Burt’s great-grandmother Ernestine (whose face Burt never had seen) and he had one of his great-grandfather Samuel Jacobs, a copy of which he sent to me. Now there is no doubt that the four sets of naturalization papers I have are those of our Cohen relatives.

May 2019

Delray Beach, Florida, USA

This story originally was published in A Gathering of Cohens: Descendants of Abraham Cohen of Gnesen, Prussia and 19th Century New York, copyright (c) 2014 by Helene Schwartz Kenvin. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

Helene faced the challenge of sorting through many records for people with the surname Cohen to establish that she had the correct naturalization papers for her family.

U.S. naturalization papers are informative documents that can be obtained from the National Archives or through various online genealogy websites, such as Ancestry.com and Family Search

JewishGen’s Family Finder was the key to Helene’s success when another researcher, a previously unknown relative, responded to her posting. This collaboration resulted in proving that the naturalization papers Helene obtained did indeed pertain to her family, providing new family history information to both of them, and allowing them to exchange old family photographs.

If you haven’t yet posted the surnames you are researching on JewishGen’s Family Finder we encourage you to do so.