by Linda Habenstreit

In

early January 2021, Jan Meisels Allen posted on the JewishGen.org Discussion

Group that the Fonds de Moscou[1]

(French Police Surveillance Dossiers of the Interwar Period [2])

were indexed and digitized by the French National Archives. This sparked my

interest. I had heard several family stories from my paternal

grandmother’s (Ernestina Steckman’s) children about their mother’s

brother, Leon Steckman.

The stories were that Ernestina’s brother, Leon, was born in 1903 and was living in Paris after having returned from working on a tobacco farm in Havana, Cuba, for a year. Leon was a waiter. He was in a tuberculosis home. He married a woman from Warsaw, Poland, who was older than he was. Leon and possibly his wife visited two cousins, Malche Linker and Anna Meltzer, in Czernowitz, Romania. In 1944, one of Ernestina’s sons remembers his mother receiving a handwritten letter from her brother, Leon, from Paris. Another son remembers that his mother thought Leon had survived the Holocaust.

After reading Jan Meisels Allen’s post, I tried to determine how to search the Fonds de Moscou files. I learned that the files are in French, which would make the task doubly difficult. A few days after Ms. Allen’s post, a JewishGen member, David Selig, posted on the discussion group that he would help others search the Fonds de Moscou. I replied, asking for help in finding my paternal great-uncle, Leon Steckman. I provided the information above pertaining to France.

A few days later I received a reply from David Choukroun, a colleague of David Selig, who searched the Fonds de Moscou and found a reference to Chaim Steckman. Mr. Choukroun said that the name Leon is a French variant of Chaim. Another discussion group member contested this statement, but Mr. Choukroun said he had a personal example of this happening in his family. I decided to let Mr. Choukroun pursue the search.

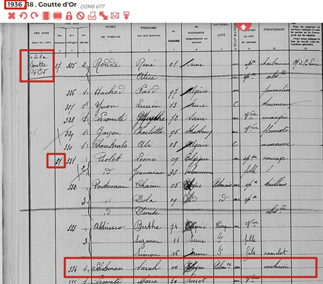

On February 6, 2021, Mr. Choukroun sent me a scan of the files in the Fonds de Moscou pertaining to Chaim Steckman. The files showed that in March 1938 the French Ministry of the Interior began investigating Chaim Steckman because he had not renewed his worker’s identity card. The files detail that Chaim complied with the French Legislation on Foreigners by renewing his worker’s identity card until 1934, when he fell ill and was hospitalized in different sanatoriums for three years. Since he was unable to work, he was unable to renew his worker’s card. The files also indicated that Chaim was born January 11, 1905, in Lieckowice, Poland, the same shtetl where I had earlier learned his sister, Ernestina, was born; that he had been living in Paris since 1924; that he was living at 31 rue de la Goutte d’Or, in Paris; and that he did not have the money to purchase a non-worker card, but was trying to get the money. In early July 1938, the files indicate that a stay of deportation was granted, pending further investigation, and Chaim was allowed to continue residing in Paris.

I was blown away by this information. While I had been waiting to hear from Mr. Choukroun, I reexamined my paternal grandmother’s family tree, which reminded me that Ernestina had a younger brother named Chaim, who was thought to have been born in 1905. None of the family stories passed down to me had ever mentioned Chaim, only Leon. I knew about Chaim because, in the 1980s, my father’s siblings had given me a Steckman family tree they had created based on informational interviews they had with their mother, Ernestina — a tree that included Chaim. I realized that my paternal grandmother and her children may have confused events in Leon’s life with events in Chaim’s life.

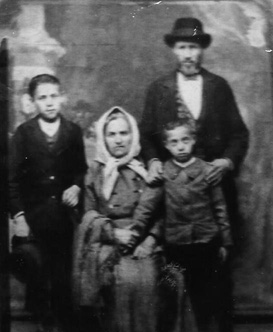

(l-r): Leon, Feiga née Breine Becker, Josef, & Chaim Itzik; 1911

On February 8, 2021, Mr. Choukroun sent more information about Chaim, including Chaim’s May 24, 1930, marriage record to Sara Nusbaum, confirming that Chaim was indeed the brother of Ernestina! The marriage record states that Chaim was a waiter, born in Liezkowce, Poland, on September 11, 1905, living at 54 rue Oberkampf, Paris. His parent’s names were Joseph Steckman and Feiga Breine Becker (Ernestina’s parent’s names), both deceased. Chaim’s wife Sara was a dressmaker, born October 3, 1900, in Wegrow, Poland, to Aron Nusbaum and Chana Ryfka Wienia.

Mr. Choukroun also found Sara and Chaim Steckman living together at 54 rue Oberkampf in the 1931 Paris Census and found Sara Steckman living alone at 18 Goutte d’Or in the 1936 Paris Census. Sara was likely living alone in 1936 because her husband, Chaim, was being treated for tuberculosis in sanatoriums from 1934-1937, as noted in the Fonds de Moscou records.

Sadly, Mr. Choukroun searched the Memorial de la Shoah Musée in Paris and found that Sarah “Stecheman,” a dressmaker, living at 31 rue de la Goutte d’Or, Paris, born October 30, 1900, in Wiagrow, Poland, was deported from the Drancy Transit Camp[3] in the suburbs of Paris to Auschwitz on July 29, 1942. No records were found at the Memorial de la Shoah Musée of Chaim Steckman. I emailed Mr. Choukroun a 1930 photo of Chaim I had obtained from my father’s sister. Mr. Choukroun sent the photo to the Memorial de la Shoah Musée. The Musée is uploading Chaim’s photo to their website and making it visible in their reading room. I am very grateful to the Musée for preserving the memory of the victims of the Shoah, including Chaim Steckman and Sara Nusbaum Steckman.

On February 13, Mr. Choukroun searched the French Archives Nationales and found an index card with Chaim Steckman’s name on it in a large box of index cards. The index card may indicate that other papers, such as a copy of a passport, work permit, or identification card, exist. The French National archivist directed Mr. Choukroun to the Archives de la Prefecture de Police de Paris in the Arrondissement where Chaim lived. This Police Archive holds records about individuals who had issues with the police, but also about the Drancy Transit Camp.

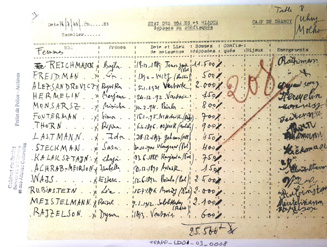

On March 10, 2021, Mr. Choukroun went to the Prefecture de Police archives center. He found a file on Chaim Steckman and one on Sara Nusbaum Steckman. Neither file provided any new revelations, except to demonstrate the heartlessness of the French under the German occupation authorities. Before being deported to the Drancy Transit Camp on July 16, 1942, Sara, along with other Jewish women, had to sign a “Statement of Sums and Jewels Deposited or Confiscated,” listing the amount of money taken from each of them. The money was deposited into a French bank — the Banque des Depots et Consignations — supposedly to pay state taxes and other expenses.

(click to enlarge)

I cannot express how grateful I am to JewishGen.org for providing armchair genealogists, like myself, with a wide variety of resources and help in finding their long-lost ancestors. At times, it seems nearly impossible to find information about my paternal grandparents and their families. With persistence, luck, and JewishGen’s and David Choukroun’s assistance, a brick wall built nearly 100 years ago, has collapsed and the secrets behind it are being revealed.

In my many years of genealogical research, I have experienced bittersweet moments when finding long-sought information has made me profoundly happy, while at the same time made me profoundly sad to learn the truth of another human being’s life and death. My genealogical research has provided me with a window into the lives of my ancestors — their successes and failures, their happy moments and their suffering. It has brought me closer to them. I feel that I am their spokesperson. I am telling their story for them, which they were unable to tell themselves. Their lives are a microcosm of the era in which they lived.

For my great-uncle and his wife, the prejudice, hate, abuse, and annihilation that they suffered during World War II is one story out of the six million stories of the Jewish people’s suffering. Maybe this story will make a difference. Maybe the lessons of World War II will not be repeated. Unfortunately, I fear that humanity is doomed to repeat the past over and over again. I pray I am wrong.

April

2021

Springfield,

Virginia, USA

_____________

FOOTNOTES

[1] The Fonds de Moscou contains surveillance information gathered by the French government, police, and military about a wide variety of people — French nationals, foreign nationals, anarchists, militants, spies, Jews — residing in France between World War I and World War II (1918-1940). When Nazi Germany invaded Paris on June 14, 1940, the Nazis seized the surveillance information and used it against the people investigated. After the allies repatriated France on August 25, 1944, the former Soviet Union took the French surveillance information. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the French negotiated the information’s return.

[2] According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, “During the interwar period, France was one of the more liberal countries in welcoming Jewish immigrants, many of them from eastern Europe. After World War I, thousands of Jews viewed France as a European land of equality and opportunity and helped to make its capital, Paris, a thriving center of Jewish cultural life. In the 1930s, however, unnerved by a significant influx of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany and the Spanish Civil War, the leaders of the French Third Republic (1870-1940) began to reassess this ‘open-door’ policy. By 1939 French authorities had imposed strict limitations on immigration and set up a number of internment and detention camps for refugees…”

[3] According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, “The Drancy camp… was established by the Germans in August 1941 as an internment camp for foreign Jews in France. It later became the major transit camp for the deportations of Jews from France… The camp was a multistory U-shaped building that had served as a police barracks before the war. Barbed wire surrounded the building and its courtyard… During the summer of 1942, the Germans began systematic deportations of Jews from Drancy to killing centers in occupied Poland… Altogether, between that first transport and the last, on July 31, 1944, 64,759 Jews were deported from Drancy… Approximately 61,000 of these Jews were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau.”

Research Notes and Hints

Linda Habenstreit learned about the Fonds de Moscou from a posting on the JewishGen Discussion Group. Through the Discussion Group, she also connected with a researcher in France who assisted her in her research. If you are not already a member of the Discussion Group, we urge you to join so that you can ask your questions and share information with other members. Join the Group by clicking here or clicking the “Connect” button on the homepage of the JewishGen Website.

For more information about the Fonds de Moscou, see the article from 3 January 2021 in The French Genealogy Blog and the Fonds de Moscou Search Guide on the French Archives Nationales website.

Other resources helpful to Linda included the Memorial de la Shoah Musée in Paris, the Archives de la Prefecture de Police de Paris, and the French Archives Nationales.