by Linda Ewall Krocker

Long ago, a few years after my father, Samuel Philip Fisher, died in the 1980s, my cousin Renee and I sat down to interview her father Benjamin (Fiszelow) Fisher, who was also my great-uncle, and her aunt Pauline (Fiszelow) Fisher, my great-aunt. Ben and Pauline were the two youngest of five children. My father’s death inspired me to delve deeper into our ancestry and somehow helped me feel closer to him and the family, even those I’d never met. The interview was awesome. I still listen to the tapes I made just to hear their beautiful, thick Yiddish accents and to refresh myself on what they told us.

(Chaim Fiszelow)

We learned so much more about my grandfather, Chaim Fiszelow (Joseph Fisher), the eldest sibling, and their other siblings, who grew up in Pinsk. I never knew my grandfather since he died in 1929, but I really loved hearing the story about his journey to America. He had been inducted into the Russian Army, and we all know how dangerous that was for a Jew – many never returned, or they came back maimed for life. My great-grandmother, Chaja Ruchel Fiszelow/Fisher (née Steinberg), made arrangements with someone to plan his escape and hide civilian clothing for him behind a particular tree on a particular day and time. As the story went, the clothing was not there, and my great-bubbe gave the man hell. The clothing was in place the following week. My grandfather changed out of his uniform and was hidden in a horse-drawn cart (a “caretta” as my great-uncle called it) under a large pile of straw. Along the journey they had to cross a bridge. Russian soldiers stopped the cart and shot several times into the straw. Luckily for my zayde (and me), they missed him!

(Benjamin Fiszelow)

The interview revealed some history. Pinsk, now in Belarus, was part of the Russian Empire prior to World War I, was occupied by the Germans during the war, and then became Polish after the war. So, while my grandfather came from Russia, great-uncle Ben and my great-grandmother, who emigrated later, came from Poland — from the same house! The border had changed.

Ben’s brother Josel met and married the girl of his dreams, so he never came to the United States. Ben recalled some cousins, in particular Zaydel Steinberg, who played violin in the Pinsk Symphony Orchestra. Ben told us that the Polish soldiers considered all Jews Zionists, and that one day the Polish soldiers broke up a meeting of local Jewish men who were discussing how to fairly distribute food sent from the United States. The soldiers sorted out 35 young and middle-aged men, including young Zaydel, forced these “Bolsheviki Revolutionaries” against the wall of the church, and shot them in what became known as the Pinsk Easter Massacre of 1919. Ben was a kid when he saw them all die.

Great-uncle Ben Fisher and his mother Ida (my great-grandmother Chaja), had been the last to come to the United States in 1923, after my great-grandfather’s death. Ben didn’t remember many details about the extended family, but he gave us enough to build out the tree. Since childhood, I had always assumed that since my family was all here, we had no one who perished in the Holocaust. Now I realize how naive I was.

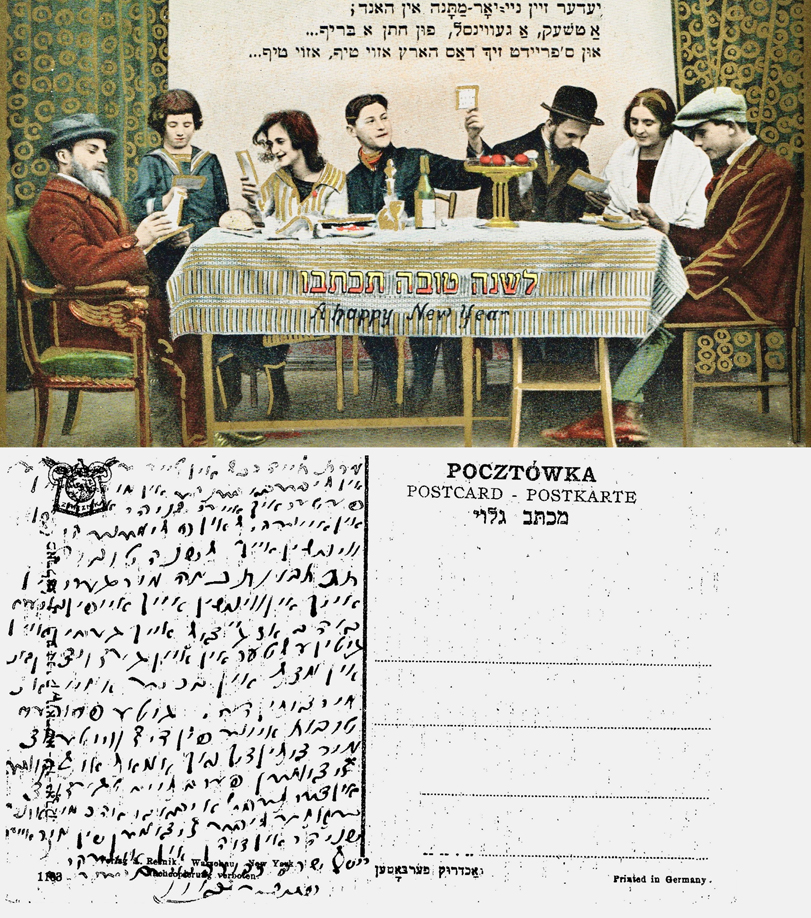

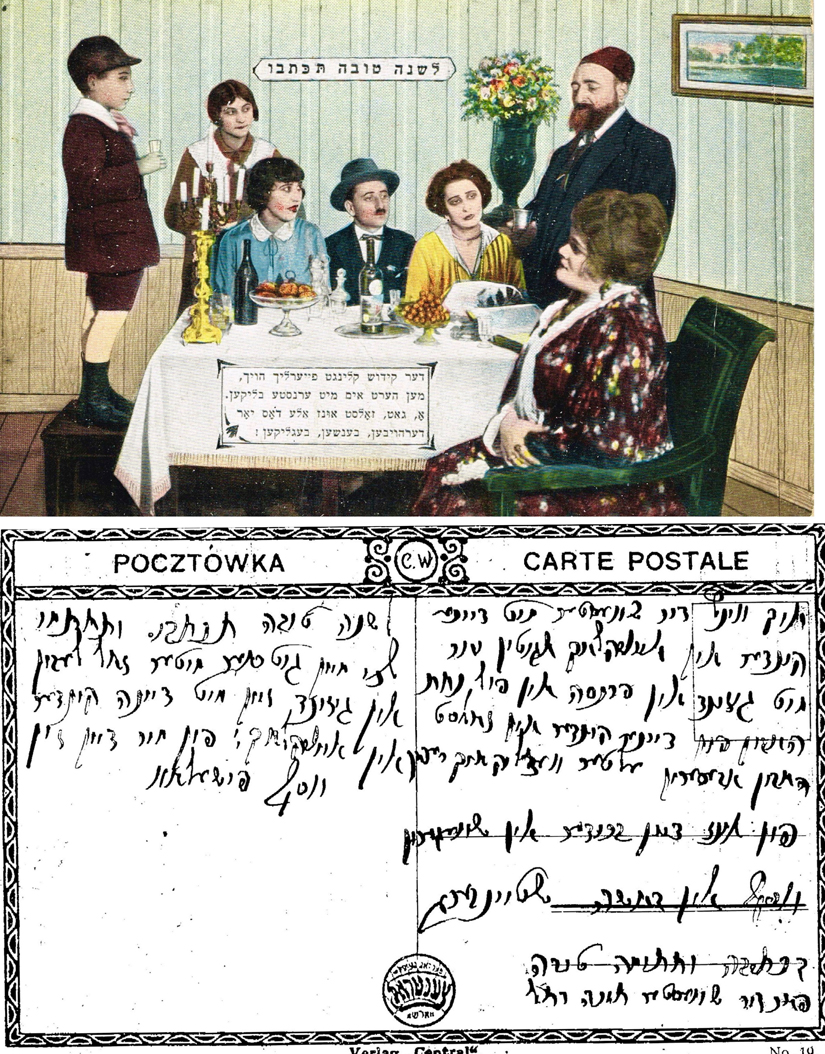

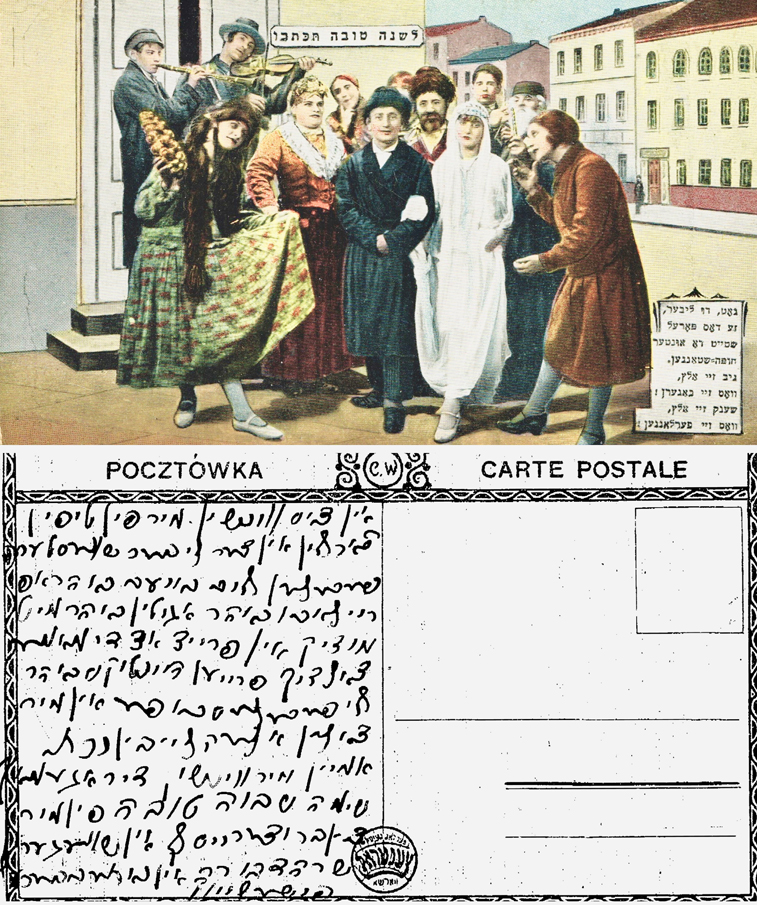

Years later I learned that my cousin Renee had her father’s correspondence from 1939-1945 from our Fiszelow and Steinberg family members who remained behind. There were postcards from a beautiful set of gilded Jewish New Year’s cards…until they apparently ran out. They then used folded paper as restrictions tightened and resources became less available. Most of this correspondence was between my great-uncles — middle brother Josel Fiszelow/Fishelov in Kachinovichi, a suburb of Pinsk, and his youngest brother Ben, and their mother Ida in the U.S. After Josel suddenly stopped writing and was presumed dead, Ben made attempts to get information from the World Jewish Congress and in 1948 contacted an unknown Fishelov relative in Israel in the hope of finding out what happened to Josel and his family. The unknown Israeli relative wrote a lovely letter back, though he didn’t have any answers. I filed Pages of Testimony for Josel and his family at Yad Vashem.

|

|

|

A few years ago, I visited Renee and we went to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. That’s where I first learned about the annual IAJGS conference that we had just missed! While at the museum, I tried to do some research on Josel and his family. That year, a 1941 German census of Pinsk, which was circulating the world, was available in the USHMM. By agreement, the database was not available outside of the museum or on the web. I found Josel’s wife’s and son’s names in the database, but Josel’s name did not appear. I learned years later that a List of Persecuted Persons included his death as a forced laborer.

Renee gave me the postcards to see if I could get them translated, and my husband photographed them all, both sides. In all, there were about three dozen cards, letters, and envelopes. I asked friends and neighbors who spoke Yiddish to try to read the cards, but no one could. The handwriting style and old style verbiage was very difficult to read, and a couple of later letters were written in pencil on faded paper, which didn’t scan well. I asked translators at Jewish genealogy events and called the local orthodox rabbi and asked if he knew anyone who could translate them, and after several phone calls, I realized I had hit a brick wall. I paid a couple of professionals to translate a few pieces. Their success wasn’t as great as the cost.

Then I discovered ViewMate on JewishGen.org and I was thrilled to learn that translators around the world could read them! I uploaded the digitized copies, a few a week, and was ecstatic when I got responses. It amazed me that so many people would freely give their time to help people around the world translate so many languages. What a wonderful free service!

The postcards were smaller and easier to translate, but the letters have to be divided into small segments for anyone to attempt them, so some of the letters are not yet done and may still hold secrets of my family’s last years of freedom before perishing in the Holocaust. One ragged letter, we believe from the youngest writer, Josel’s son, Nuchem Berel, gave us the distressing news that all the other family members had ultimately perished in the summer.

I eventually discovered that Yad Vashem’s website had no information about all the relatives uncle Ben had named, so I filed 21 Pages of Testimony with whatever information I had. I also discovered that Nuchem Berel had survived and moved to Israel, where he also filed a Page of Testimony for his mother. He may not have known how his father died, and Nuchem died in the 1970s, years before I could try to locate him.

I made a lovely scrapbook of the correspondence in safe protective pages so that no one would need to handle the originals. My cousin and I decided to donate the correspondence to the USHMM, who in return translated a couple more letters.

Remember the “unknown Fishelov relative in Israel” mentioned earlier? Several years ago, Renee Googled the name Fiszelow and emailed a David Fishelov in Jerusalem. We couldn’t figure out the connection. A year later she found another, Moshe Fishelov in Tel Aviv. Small world, it turned out that they’re brothers, sons of the 1948 letter writer, Nakhum Fishelov. Moshe paid a researcher to explore his ancestry, and shared the Belarussian document he received. Google Translate and two Russian speakers here in the U.S. helped us make some sense of it, and we found our connection. Moshe also sent me a Hebrew book his father had written about the story of his post-Holocaust migration from Pinsk to Israel and translated the relevant information. Maybe that needs to find a home in a museum, too.

Thank you, JewishGen. Thank you so much for ViewMate. It is an invaluable service that deserves to be brought to light!

August 2019

Langhorne, Pennsylvania, USA

Research Notes and Hints

Linda and her cousin

Renee gathered valuable information about the family’s history when they

interviewed older relatives. If you have older relatives you haven’t

interviewed, we encourage you to do so before it’s too late.

Linda was fortunate that Renee had some of her father’s old postcards and letters from family members in Poland. Translating the old-fashioned script proved difficult until JewishGen’s ViewMate provided the breakthrough.

A visit to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. proved fruitful for Linda.

For more information about the Pinsk Easter Massacre of 1919, see an account in the Pinsk Yizkor Book on JewishGen. This Wikipedia entry includes photos of the victims and a list of references. You can read an article about it from Haaretz. An account is included in the book The Jews of Pinsk – 1881-1841, by Azriel Shohet and Mark Jay Mirsky.