by J. A. Koso

As a descendant of ancestors who crossed the Atlantic by ship from Europe to North America, I have been interested in how this was managed, as I assumed that my ancestors lacked sufficient income to accomplish this odyssey. While I was researching the ancestry of my step-father, Dr. Fred Bookstein, I located members of his family on a passenger list for the SS Kursk, departing the port of Libau, Latvia on 9 May 1911 and arriving later that month at the port of New York. The ship manifest entries consisted of my step-father’s grandmother Freida Safron, age 32, and her four children, Moisey, age four; Elia, age eight; Judiss, age six; and Luba, age two.1 Judiss, later named Judith Yetta, was Dr. Bookstein’s future mother. The family was joining their husband and father, Elias Safron, who was living in Detroit, Michigan. The ship manifest indicates that the family may have arrived with $25.00.

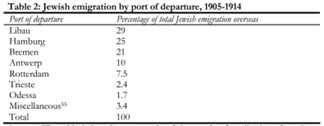

A family leaving the Pale of Settlement between 1905 and 1914 had about one chance in three of leaving through the port of Libau (see table 2, below).2 29% of all Jewish emigration during the early twentieth century, before the Great War of 1914, went through the port of Libau (Latvia), the most frequently used port of embarkation during this period.

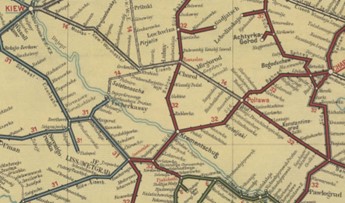

The distance travelled to Libau could be long, and the question of how it was financed comes to mind. According to the SS Kursk passenger list, the Safron family was from “Russia” and “Pawlograd”. This is the German name for Pavlograd (in Russian), which is now known as Pavlohrad, a city located in eastern Ukraine. The Wikipedia page for Pavlohrad states “In the 1870’s, a railway connecting St. Petersburg and Simferopol, in the Crimean Peninsula, passed through Pavlohrad”3. A 1912 German map of the Russian Railroad System (the map below) shows that Pawlograd had a railroad station and probably also a telegraph office4. The map also indicates that the distance between Kiev and Poltava/Poltawa is 338 kilometers or about 210 miles. Using modern online maps, and assuming total train distance in 1911 was not too different from total modern driving distance, then the distance from Pawlograd to Libau would’ve been 1,082.21 miles (139.13 miles from Pawlograd to Poltava; 209.56 miles from the latter to Kiev; and a final 733.52 miles from Kiev to Libau).

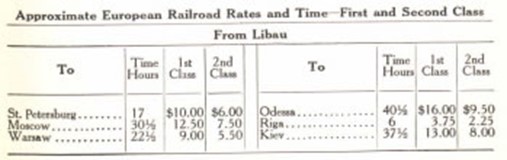

In the Russian American Line pamphlet (see table below)5, the approximate cost of a second-class railway ticket from Libau (Liepāja, Latvia) to Kiev is listed as $8.00.

What the additional train fare would be from Pawlograd to Kiev is not known. However, assuming that ticket fares are a function of travel distance, the estimated 2nd class fare to travel from Pawlograd to Libau in 1911 would be about $11.80/person [(1,082.21/733.52) x $8.00/person = $11.80/person]. If we make a further assumption that children travel at half fare, the train fare for four kids would be $23.60 [4 x $11.80/person x ½], making $35.40 the total train fare for the five-member Safron family.

According to the website for the PBS Show Destination America, “By 1900, the average price of a steerage ticket [Europe to the USA] was $30”.6 Based on the average annual inflation rate of 1.13%/year between 1900 and 1911, the cost of a 1911 steerage ticket would’ve been $33.95 [$30 x (1.0113)11 = $33.95 in 1911]. 7 Again, assuming that children traveling in steerage will be charged half fare, the four Safron children’s ship fare would be $67.90 [4 x $33.95/person x ½]. In 1911, then, the five Safrons would have paid an estimated steerage cost of $101.85.

The approximate total transportation cost, train plus ship, in 1911 dollars, for the Safron mother and her four children, comes to $137.25 [$35.40 + 101.85]; in 2024 dollars the estimated fare comes to $4,537.477.

The information contained in the article Out of the Shtetel. In the footsteps of Eastern European Jewish migrants to America, 1900-1914 allows us to determine the travel costs using different data, as a check on the above estimates. This article states that “The [ship] fare from Libau (Liepaja), Latvia to New York was 70 rubles per person ($35, equivalent to $714 today [2007]), again with children traveling for half price.”8 Taking into account the four Safron children, the total ship fare, in 2007, is estimated to be $2,142 [$714 + 4 x $714 x ½]. Since this figure does not take account of train fare, we can correct for the deficiency by adding $35.40 from our previous 1911 train fare calculation; projected to 2007, this becomes $722.16 [((714/35) x 35.40)]. Thus, ship plus train fare is estimated to be $2,142 +722.16 = $2,864.16. Projecting this result from 2007 to 2024, we obtain a total fare of $4,358.16 [$2,864.16 x (1.0250)17], compared with the first set of calculations of $4,537.47, a difference of about 4.1%.

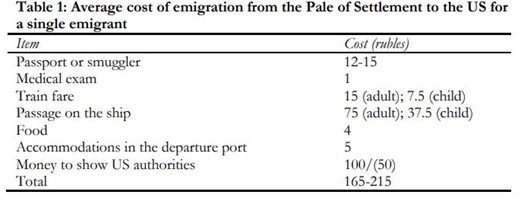

For uniformity in comparison, I only used transportation data. Table 1, below, illustrates the cost of other travel expenses [note that table 1 is for travel from ports other than Libau]. Passport costs could vary depending on whether the four children used a group passport as was not unusual. If so, the cost for two passports (mother and grouped children) would be 24 or 30 rubles. Five medical exams: 5 rubles; food: 20 rubles; port accommodations could be anywhere from 15 to 25 rubles, depending on how the children were treated (at full cost or half cost). Also, food and hotel costs would vary on length of stay in Libau. Total incidental cost, at a minimum, would be 64 rubles or $32 in 1911, equivalent to $1,062.06 in 2024.

Thus, the estimated grand total travel cost for the five Safrons is $5,420.22 [$4,358.16 + $1,062.06] in 2024 dollars (in 1911 dollars it is $162.93).

In 1914, 69% of American workers earned less than $2,000 a year12. The estimated 1911 total travel cost for the five Safrons of $162.93 [5,420.22/(1.0315)113] is 8.15% of $2,000 or about four and a quarter weeks wages.

There are several articles that state how horrendous the conditions and the food were for people traveling from Eastern Europe to America. Some, bringing their own food, placed themselves at risk of running out of food or getting robbed. There are stories of those who were so poor that they would be begging for food from the 2nd and 1st Class Passengers. Steerage passengers were locked into their place to prevent them from begging.

Elias Safran arrived in New York on 5 October 191013. It is unlikely that he raised all of the passage money for his wife and four children by himself in less than one year (in about 8 months – early Oct. 1910 to late May 1911). According to Dr. Bookstein, there were already other members of the Safron family in the Detroit area; these family members may have funded the cost of passage. It is also possible that there was aid from the community in general or from a benevolent society. Exact financing remains unknown.

For most of the working people in this time period, 8% of their annual income would take quite some time to acquire. Clearly, it took a great deal of effort for a family in America to save and/or borrow enough to bring their relatives from Europe.

Using the technology available at the time, it would not be a problem to wire the required funds from Detroit to pay for the steamship tickets, the railroad tickets, and a telegraph message from Libau to Pawlograd.

The Liner SS Kursk14 of the Russian American Line15, having departed the Baltic port of Libau on 9 May 1911, arrived at Ellis Island, New York on 23 May 191116.

_______________

J. A. Koso has been a Family History Researcher since the late 1970’s. He is available for research work and can be contacted at jakoso@gmail.com.

No warranty is implied on the part of JewishGen and providing Mr. Koso’s email address is provided only as a convenience. All researchers are encouraged to investigate Mr. Koso privately, thus performing due diligence prior to engaging in any contractual arrangement.

SOURCES

1 New York, U.S. Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (Including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820 – 1957

(The National Archives and Records Administration – available on Ancestry.com)

2 Alroey, G. (2007). Out of the Shtetl. In the footsteps of Eastern European Jewish migrants to America, 1900 –

1914. Leidschrift: Organisatie En Regulering Van Mifratie In De Nieuwe Tijd, 22 (April), 91-122

Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/188/73038 p 96 [herein after Alroey]

3 Wikipedia page on Pavlohrad (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavlohrad) [viewed 20 April 2024]

4 University of Wisconsin Libraries, American Geographical Library Digital Map Collection,

1912 German Map of the Russian Railroad

(https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/18644/rec/207)

5 Pamphlet of the Russian American Line from the Yale Library

(https://search.library.yale.edu/catalog/6460861?block=Other )

6 Website for the PBS Show Destination America

7 In 2013 dollars.com (https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1900)

8 Alroey, p 96

9 Ibid, p 98 Author will use the exchange rate stated in text of 1 ruble = $00.50 USD

10 A combination of the table’s numbers and the Author’s calculations

11 Alroey Op. Cit, p 99 “If a woman told the US immigration clerks that she was joining her husband, she did not

have to show the minimum amount of money to enter the country”

12 University of Missouri – Prices and Wages by Decade: 1910 – 1919

(https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1910-1919)

13 “Certificate of Arrival-for Naturalization purposes”, in Author’s Collection;

1920 United States Federal Census of Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan, ED 113, p 11A;

1930 United States Federal Census of Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan, ED 82-224, Sheet No. 25B

(National Archives and Records Administration – available on Ancestry.com)

14 Wikipedia Page of the SS Kursk (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Polonia_(1910) ) [Viewed 20 Apr 2024]

15 Wikipedia Page of the Russian American Line (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_American_Line)

[Viewed 20 Apr 2024]

16 See footnote #1

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

The author, Mr. Koso, used a variety of publicly-available sources, including census records, ship manifests, Wikipedia articles, and papers and maps located in the libraries of the universities of Yale, Missouri, and Wisconsin. An unusual and surprising source was the PBS website! A researcher, one can conclude, should always think “outside the box”.