by Shaul Yannai

The emphasis in the following “success story” is more psychological than genealogical. I decided to present the story this way for two reasons: first, the specific lineage is a personal family matter and has no particular relevance to the general reader. Of course, it is impossible not to mention names. But it is the same for all people. Father, mother, uncle, etc. Second, my focus will be on not giving in to despair. By losing hope we forfeit the search, we forfeit the knowledge that accumulates through searching, and we forfeit the possibility of discovery.

Let me begin with some background information: my sister (born in 1946) and I (born in 1952) are the children of Holocaust survivors from Lithuania; we were both born in Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania. Our mother, Masha Sher, survived Ghetto Kaunas and our father, Jacob Goldin, was in the Russian Army that fought the Nazis. Our mother passed away in 1956. In 1959 our father made “Aliyah” with the two of us, and we lived in Israel until he passed away in 1970. I share this information in order to highlight the fact that not only were our parents Holocaust survivors, but after the war they were under Soviet Union rule in Lithuania. As a result, in a very deep sense they were also refugees in the country of their birth. The Lithuanian collaborators with the Nazis did not want the Jews (otherwise they would not have murdered them wholesale) and the Russians moved the Jews around according to circumstances or did not allow them to move at all. Thus, the combination of being survivors and refugees played a key role in what information was passed on from the generation of survivors to their children.

In our case, as in the majority of cases of Holocaust survivors, what was passed on was the deafening throes of silence. This silence served two functions: to protect the survivor from the unbearable pain of first-hand experience and memory, and second, to protect the second generation from the trauma of the first generation.

With respect to our mother’s family, we literally knew nothing apart from three “facts”. We did not even know the names of our mother’s parents or sisters. This is what we knew: first, that our mother was from Kretinga; second, that there was a rabbi in her family somewhere in Latvia; third, that her mother was a seamstress. Our ignorance was overwhelming. Some of it thawed a bit after a visit to the Lithuanian State Historical Archives in 2008, the year we began researching our family roots fearlessly, with seriousness and devotion. Until then the wall of silence disabled our capability to even know what questions to formulate. We were unconsciously focused on maintaining the sacredness of the wings of silence that were our protection than sharpening the ability to probe into the pain from which we were protected .

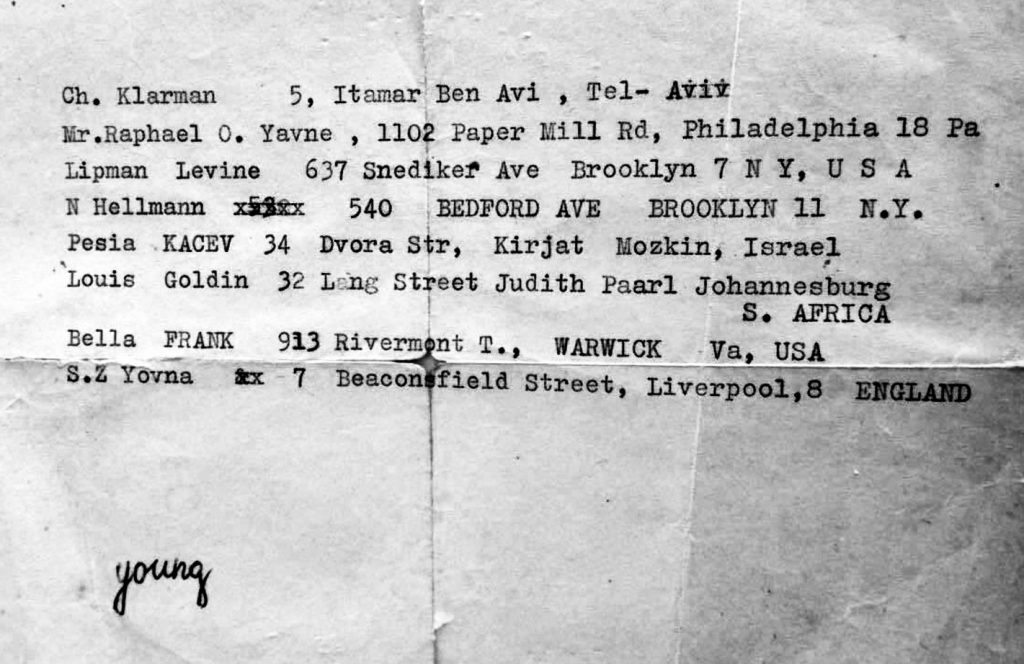

About three years ago, in 2016, my sister discovered a note written by our father with the names of nine people, a note written sometime between 1946 and 1970. Eight of the names also had their addresses: two in Israel, one in South Africa, four in the United States, and one in England. At the bottom of the note the word “young” was written. We knew the people in Israel because both were from our father’s side. We knew who the person from South Africa was because he was also related to our father. All the other names were completely strange to us.

I naturally began researching on the Internet all the unfamiliar names listed on my father’s note. One of the names (I cite it as it was written on the note) was Lipman Levin. At a certain point I landed on the “kevarim” website. The Hebrew word “kever” (singular of the plural “kevarim”) means “grave” or “tomb”. On the kevarim website the name appeared as Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Levine. On the Rabbi’s specific page there were a few comments by different people, including one from his great-granddaughter. Another comment was from Mordechai Hellman. On my father’s note was written the name N. Hellman. At this point it became obvious to me that I struck gold. But there was no contact information for Mordechai or the great-granddaughter. So I took a risk (despair has its advantages) and left a comment, including my email address, asking Mordechai to contact me because we may be related. That was on December 30, 2017. I had no other choice but to wait till the “manna” would fall from the sky.

On June 7, 2019, I received an email from Reuven Hellman saying that Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Levine Z”L was his great-uncle. From this point on the “manna” starting falling with fantastic generosity. Reuven is the son of Moishe Hellman, Mordechai Hellman’s brother. I sent Reuven my father’s note and he knew who “Young” was. The Hellman branch and the Young branch knew one another all along. For my sister and me, all this was new. We discovered that we share with the Hellmans and Youngs the same great-grandparents, Moshe Sher and Ester Michla Glaz.

Through the Youngs we received a photo of my mother’s parents and sisters, shown below. It was the first time my sister and I ever saw a photo of our maternal grandparents and my mother’s sisters. It was given to us by Moishe Yitzchok Young, the son of Hana Sher, who was the sister of Yankel Sher, the father of our mother.

Below is a photo of our grandparents, their four daughters and our grandfather’s sister (standing in the middle) taken in 1934 in Kretinga. From right to left: Sara Sher, Yankel Sher, Chaya Sora Sher (standing), Esther Sher, Rachel Lea Sher (née Elterman), Devora Sher (seated), and standing behind Devora is our mother, Masha Sher.

Through the Hellmans we received an 831-page book composed by Mordechai Hellman that meticulously delineated, with impeccable love, and plenty of photos, the story of the Hellmans, their ancestors, and all known branches to them. Through that book we discovered that the above-mentioned rabbi in Latvia was in fact Rabbi Nakhum Sher. He was the father of Chaya Bluma, who was the wife of Shraga Hellman and the mother of Moishe, Mordechai and six others. Nakhum Sher, the last Rabbi of Daugai (Doig) in Lithuania, was never in Latvia. Nakhum was the brother of our mother’s father, Yankel Sher.

In the photo below, taken on September 22, 1946, at Penn Station in New York, we see from right to left: Rabbi Uri Shraga Hellman, his three-year-old son, Moishe Hellman, being held and kissed by Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Levine, who came to greet them upon their arrival from China to the USA. Rabbi Hellman was among the Mir Yeshiva group that moved from Lithuania to China just before the war.

The bottom line for my sharing this family genealogical saga is that the name “Sher” did not appear in the original note that had nine names on it. Therefore, if as a researcher you will focus only on the primary branches in order to guide you to all the other branches (this inclination is almost like an instinct), you may easily overlook key and vital information; because the focus of your research will be limited by the point of departure you adopt as your method of research. In our case, we really had no choice because, with respect to our mother’s family, we had no clue which branch was primary and which was secondary. Thus, it is through the secondary branch, through Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Levine, that we by sheer luck and grace, were able to discover some of the primary branches in our mother’s family.

For the sake of precision, this is how Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Levine was related to us: he was the son-in-law of Rabbi Yekutiel Zussman Brodny, the father of Neche Brodny who married Rabbi Nakhum Sher, who was the brother of our grandfather, Yankel Sher.

Thank you JewishGen, Reuven Hellman, Moishe Hellman, Mordechai Hellman, Moishe Yitzchok Young, and Eli Young.

January 2020

Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov Ichud, Israel

Post Script: In an email to the Editor about his Success Story, Shaul Yannai wrote that although JewishGen resources did not play a direct role in this success, “…All the experience I gained in the past 10 years through JewishGen gave me the confidence to pursue the direction I took in the research… I cannot separate the psychology of my experience of all the research I did in JewishGen … from the great luck that I write about in the article. Without JewishGen in the background, I would probably have given up the continuous search altogether. JewishGen is more than method or tools. It is also spirit!!”

Editor’s Research Notes and Hints

Not unusual in the families of Holocaust survivors, Shaul Yannai and his sister had been told very little about their mother’s family or her survival in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto in Lithuania.

Shaul’s serious research began with a visit to the Lithuanian State Historical Archives in Vilnius.

The discovery by his sister of an old type-written note by their father was a turning point. Diligent online research regarding the unfamiliar names in the note led Shaul to the Kevarim.com website. A response to a comment he left on the website subsequently led him to previously unknown living family members, family history, and photographs.

For more information about Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania, see JewishGen’s Kovno KehilaLinks webpage and an excerpt about Kaunas from the “Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities. Lithuania”. [Note: Shaul Yannai was one of the translators of the Encyclopaedia.]

JewishGen and the Yizkor Book Project posted “The Holocaust in 21 Lithuanian Towns”, which includes Kretinga, the hometown of Shaul’s mother. See also JewishGen’s KehilaLinks webpage for Kretinga.

LitvakSIG (Lithuania Special Interest Group) is a very helpful resource to researchers with roots in Lithuania.