This article, published in the Jewish Chronicle Colour Magazine on 28 November 1975, is reproduced with kind permission of the Jewish Chronicle. It was initially reformatted by Louise Messik for inclusion in these web pages (and subsequently by David Shulman). Some of the original photographs have not been reproduced.

Jews came to Wales between 1880 and 1914 much as they did to other parts of the British Isles, to see refuge and eke out a livelihood, to settle and find peace. But there is a special lilt to the story, a Welsh dimension which adds both romance and pathos to the rise and fall of a community.

The special dimension is heightened by the coincidence of the period of immigration with the life and death of King Coal in that 'greenhouse of calamity,' as playwright Gwyn Thomas has called South Wales.

The first documented Jewish presence in Wales was in 1749, when David Michael came to Haverfordwest from Germany to start a banking business. (There are traces in the records of a few Jews in North Wales in pre-Expulsion times when, according to the late Cecil Roth, Jews also lived and traded in those parts of south and central Wales 'which were under English influence.' But there does not seem to have been any organised Jewish Life.)

His son Levi was the first Welsh born Jew (1754). In 1760 or thereabouts he settled in Swansea (West Wales, for whatever reasons, has not been fertile soil for Jewish settlement) and attracted other Jews to the town, which granted a plot for Jewish burial in 1768. Cardiff came next; the community there dates from 1840.

But Jews really started coming to the Principality in any numbers in the 1870's,

when the advent of the steamship and the gathering industrialisation of Britain

built up the enormous demand for coal and steel. Thus Tredegar, at the 'head' of

the Rhymney Valley, had a community in 1870, the coal and steel town Merthyr

Tydfil a Jewish Cemetery and

synagogue in 1872, and there was an earlier one. Local records discovered by Mr

Maurice Dennis of Cardiff, historian of Welsh Jewry, mentions a synagogue in

Neath in 1875 with 'seats for 30.' No other trace of an organised community

there survives, although quite a few Jews are known to have lived there.

From 1880 onwards Jewish settlement spread into almost every town and village of the Welsh valleys and Aberavon, Aberdare, Abertillery, Bridgend, Ebbw Vale, Pontypridd, became names familiar in the Anglo-Jewish directory. Brynmawr, according to the statistical unit of the Board of Deputies, at one time had the largest concentration of Jews in proportion to [its population, in] the British Isles.

Some immigrants also settled along the coast of North Wales, and Bangor, Llandudno, Colwyn Bay and Ryhl support small Jewish communities to this day. But they are now miniscule though they endeavour to maintain some semblance of communal life centred on the synagogue in Llandudno.

But our story unfolds in the valleys of South Wales, an area bounded in the west by Llanelli and Raglan in the east, Brynmawr in the north and Cardiff in the south. And this is the area I visited.

"Look you, bach, the synagogue's still there, but it's dilapidated, closed these many years. Most of 'em gone - I knew them all."

Port Talbot, on the south coast nine miles east of Swansea, has been undergoing a revival, nourished by one of the largest steel mills in Europe. The down-at-heel reminders of the old town are giving way to Welfare State development. I had floundered round the still undeveloped back streets looking for Tydraw Place, and the synagogue said to be standing there in particular.

The late Mr Isaac Factor, for many years (since the 'twenties) president and secretary of the congregation, had retired to the loving care and modern appointments of the Jewish Home for the Aged in Cardiff, and there was only this friendly Welshman to direct us.

Apart from two shopkeepers, nothing remains of a once flourishing community but

a memory, of strangers who became accepted neighbours but remained strangers,

and who left as unaccountably as they had come. Of the synagogue, opened in 1921

by - as a just-legible plaque proudly proclaims - I. J. Fine, JP, of Cardiff,

nothing remains but a crumbling shell. After a long struggle, the Scrolls and

appurtenances were transferred to Cardiff for safe keeping.

The story is repeated, with variations, in other towns in south Wales with names which ring in the historic and tragic history of these parts in the last century; Tredegar. where the synagogue is now a private house, next door to Mr Michael Foot's cottage; Ebbw Vale - synagogue demolished, along with the adjacent chapel, for redevelopment; Bridgend - now a shop on its High Street site; Abertillery - now a furniture depository; Aberdare - gone; Brynmawr - only the cemetery is left, with the only Jewish survivors, Mr and Mrs J. H. Lyons, as faithful guardians, from a flourishing community which for a time early this century boasted two congregations, the 'ins' and the 'outs' (or, if you prefer, the 'pros' and the 'cons').

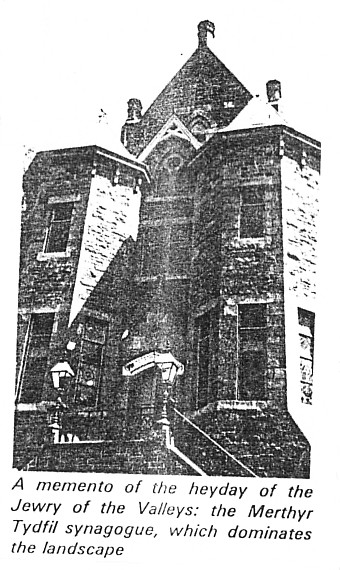

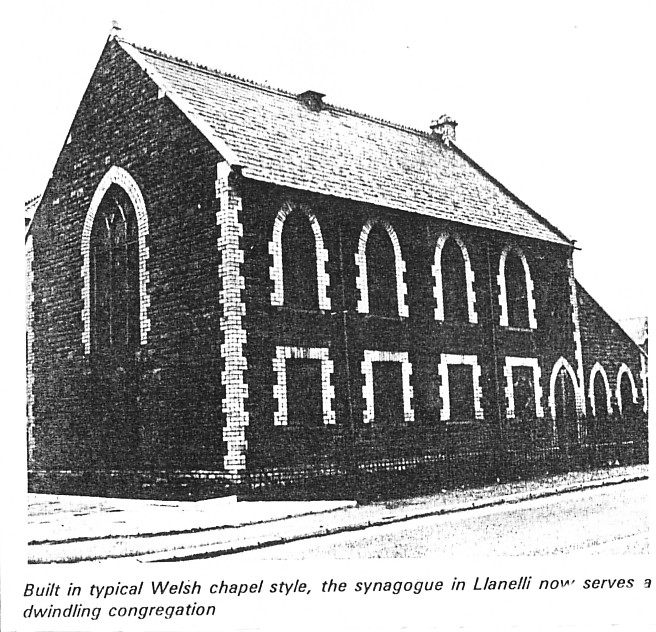

In other places the synagogue remains standing, magnificent if melancholy reminder of valiant efforts to transplant Jewish ways, tradition and togetherness into unpromising soil: Pontypridd - a fine building, in the classic Welsh chapel style, which in recent years has been opened only for the odd wedding or other simcha for the handful of Jews who pray in Cardiff or Newport on the Festivals; Merthyr Tydfil, whose imposing synagogue, maintained by a legacy from the late Abe Sherman, who was born and died there, dominates the landscape;

Llanelli, another fine building maintained

by the proud remnants of a once proud, lively and scholarly congregation -

'the Gateshead of South Wales,' as the sole local survivor of the Landy

family called it. (It was also quarrelsome and, like Brynmawr, boasted an

'opposition' shul for a time).

In other places still no trace is left of the synagogue, and in some nobody remembers whether there was ever one - although Jews certainly lived there.

There is of course Cardiff, and there are Swansea and Newport, but more of these later.

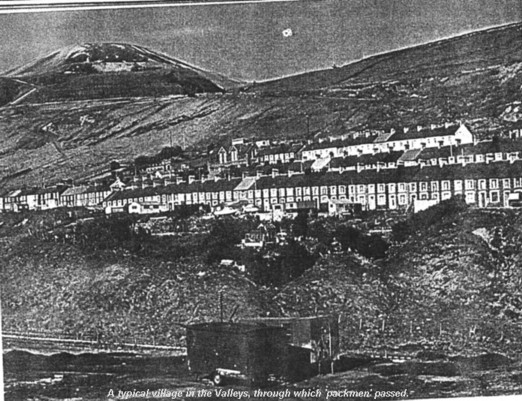

The brooding hills and green valleys of South Wales are evocative of so many things. To the Jewish traveller they speak of a life's story exceedingly strange and affecting. He sees an alien figure bent low under his outsize pack, walking up hill and down dale for mile after lonely mile. At the mining village tucked away beneath a dark hill, children greet him with: "The packman has come!" He knocks on doors, his only English words, "anything wanting?" (Welsh is a double-sealed book.)

Come Friday, he makes for home and family, Sabbath in synagogue and the Chevra Shass, the talmudic study circle. He is a learned Jews, among the few precious possessions he has brought from in der heim is his shass, his well-fingered volumes of the Talmud, and a desire to 'learn' more. He has brought his determination to keep 'the Law' whatever the difficulties. And so if he was caught on his way by the advent of the Sabbath, he would leave his pack and the small pile of money he had earned on the table of a friendly miner's cottage, and come back for his treasure on Sunday knowing it would all be there untouched. (Later, he or his sons, having moved to Cardiff, would organise a minyan for morning prayers on the train taking them into the countryside on business.)

He and his fellow-Jews would have engaged the services of a shochet who not only

provided kosher meat, but taught the children every day after school hours,

conducted services and officiated at weddings and burials. He would also

probably have provided a mikva (ritual bath) though in time its upkeep

would tend to be neglected. Often the shochet and the Hebrew classes took

precedence over the building of a synagogue, and there were communities, some

quite large where they never got round to building one.

And if the community was too small to muster 20 or 25 shillings or so which were the shochet's weekly pay, or the members were too poor to find sixpence for the weekly membership contribution, the children would walk across the hills, sometimes four or five miles, three or four times a week to the nearest cheder, summer and winter, rain or shine (mostly rain).

Jews in these places had plenty of practice in walking across the hills. One duty which they never neglected was accompanying the dead on their last journey (and there was no shortage of these, particularly when times were hard and many died in childhood or child-birth).

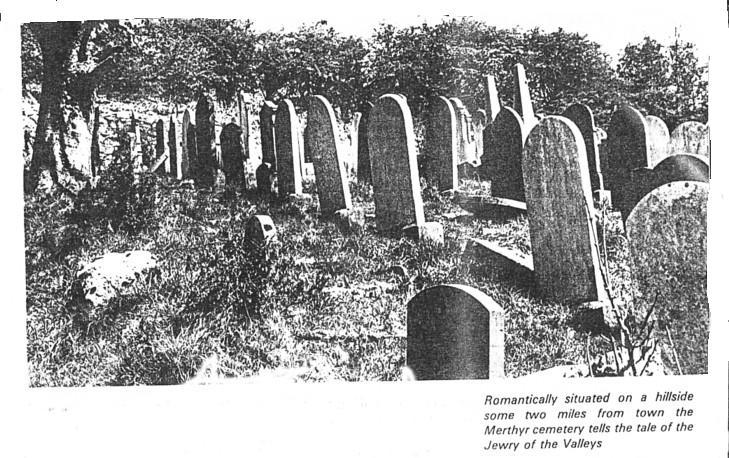

There were only three cemeteries, in Swansea, Cardiff and Merthyr Tydfil (Brynmawr's was only opened in 1920, as the result of a quarrel with the Merthyr people. There is also a mysterious local record in 1904 of a Jewish cemetery in Brecon in the heart of the majestic Brecon Beacons - mysterious because there is no trace of Jews ever having lived in that area). The whole community would walk after the hearse, the only vehicle, whatever the distance. Former residents of the valleys still remember a public house not far from the Merthyr cemetery where the mourners would rest and refresh themselves before setting out on the return journey.

Were all newcomers packmen? By no means. Some, yes, went to work in the coal

mines and steel mills. Mr Lewis Hamburg of Cardiff remembers when he was saying

kaddish in 1941 he would find a regular minyan at Bargoed, half-way up the

Rhymney Valley (although it never had a synagogue). About six members worked on

the coke ovens, another half-dozen in the mines. They were sons of working-class

immigrants, and he reflects that they were "very yiddishlech," strictly

observant and knowledgeable; one miner conducted the service beautifully in the

best Welsh manner.

There were some Jewish miners elsewhere too, eg in Brynmawr. Mr. B. Hamilton of Merthyr recalls his father telling of a group of chasidim who came to his town and worked in the steel mills. They even brought their own 'Rebbe' with them. But apparently they did not last long and went on to America.

Many a 'pack' became the nucleus of a big business, usually located in Cardiff; other immigrants became property owners. It was these latter who are widely taken to have been the cause of the only anti-Jewish outbreak in Wales, in Tredegar in 1911. The riot is still remembered by the sole surviving Jewish resident of that town, Miss Bernstein. Her father settled in Tredegar 95 years ago and she "couldn't live anywhere else," although she is happy to see a Jewish face and gets her JC from the local newsagent every Friday.

The riot happened on a Saturday night: all the 'Jewish' shop windows were broken but, she said, nobody was hurt. Nevertheless, Winston Churchill, who was Home Secretary, sent in the troops. I heard many differing opinions of that riot. My own view is that it was part of the general unrest among Welsh miners at the time (troops were sent elsewhere too) and the anti-Jewish element was marginal, an optional extra. In any case, the riot did not spread to neighbouring Jewish communities. At Brynmawr the police sergeant (whose son subsequently became Chief Constable of Cardiff) personally confronted the rioters and turned them away.

But if there is no distinct Welsh antisemitism, what was and is the native attitude to the Jews in their midst? And do the Jews think of themselves as Jewish Welshmen or Welsh Jews? Looking for straws in the wind it seems to me not without significance that in Cardiff and Swansea, where there are (or were) old and new synagogues like the 'United' and 'Federation' in London, the old is known as the 'englisher shul' - rather a give-away that.

We met only two Welsh-speaking Jews, both in Swansea. I gather there are others, though not all that many. But then the parts of the country where Jews settled are not by and large Welsh-speaking. I am told that the Jews in North Wales do speak Welsh, but possibly from necessity as much as from choice, for the country people in those parts do not speak English (or choose not to).

What emerged clearly from my talks with Welsh Jews is that while they are grateful to the country that welcomed them and are friendly with their non-Jewish neighbours, they will never be able to sing 'hen wlad fy nhadau' (the Welsh national anthem) with true Welsh fervour. As one of the Welsh-speaking Jews told me, only half in jest: "To be a real Welshman, you must be chapel."

And on the Welsh side? Perhaps an unconscious answer was given me by a Welshman in Tredegar who replied, when I asked him about a former local resident, "He's not a Welshman, he's a Jew." And this Welshman was one of many, who remembered their former Jewish neighbours with affection, and a certain amount of admiration if not awe. He told me of a widespread belief, which he obviously shared, that the prosperity of a town depended on its Jews: "If the Jews go, the town goes down," was the saying.

What is clear is that however long Jew and Welshman lived side by side, however much they came to rely upon and trust one another, a real communications barrier remained. The Jew remains a kind of mascot, who brings you luck.

Of course there were and are exceptions. Mr Ben Hamilton is a highly respected solicitor in Merthyr Tydfil, coroner for the town and mid-Glamorgan. He and his hospitable lady are known, liked and respected by everybody. When we arrived on the town's outskirts looking for him the first traffic warden we asked figuratively rolled out the red carpet for us all the way to his office. At the same time, Mr. Hamilton is the Jewish community and guardian of its cemetery and has been since the twenties, as was his father before him. His grandfather settled in Merthyr from Manchester. But this kind of well-integrated, self-confident Jew, without any kind of pack on his back, and with deep roots in Welsh soil, is rare.

Jews have been fairly active in the life

of the community in which they lived and their contributions in many

fields out of proportion to their numbers - well under 2,000 in 1900,

nearer 5,000 in the twenties, and down to some 3,000 today. The greatest

single Jewish contribution to Welsh prosperity was made by German

immigrants who came to Wales in the thirties and largely built up the

Treforest Trading Estate, a light industry complex which infused life into

the dying Rhondda. This contribution, a pilot scheme which came good, has

received much official recognition. And the first and only

English-speaking Theatre in Cardiff, which was donated by the Harry and

Abe Sherman Trust (and is called the Sherman Theatre).

But while there have been two Jewish Deputy Lord Mayors of Cardiff neither advanced to the top position, and other civic honours are bestowed somewhat sparingly - though Mr Harry Cass of Llanelli, a jeweller and hon secretary of the community, was appointed JP while we were there.

The first Jew to sir for a Welsh constituency is Mr Leo Abse, MP for Pontypool ("his grandfather could learn a blatt," Mr Hamburg, a much-travelled Cardiffian informed me). I have it from the same source that Sir Alfred Mond failed to carry Swansea many years ago because he was a Jew.

An exceptional Jewish contribution to the Welsh cultural life was pointed out to me by the historian, Mr Dennis. Bertram Marks, secretary of the Cardiff Synagogue, was a portrait painter of note and his work is represented in the National Museum of Wales. His subjects included royalty.

But on the whole it seems that, much like their fellow-Welshmen, Jews had to leave for the great world outside to make their mark. Lord Janner hails from Barry, his son Greville from Cardiff, as do the other labour MP's, Leo Abse, (as well as his writer brother Dannie) Maurice Edelman and Maurice Orbach. Welsh Jews who made it in business include Rosser Chinn of JNF fame.

The Landys including Rabbi Maurice Landy, came from Llanelli, which, true to its 'Welsh Gateshead' claim, also produced Rabbi Isaac Cohen, for many years, Chief Rabbi of Ireland.

But what is left behind? The Second War finished what the coal slump of the 'twenties and the Great Depression of the 'thirties had started. Gone are they all from the valleys, all but a few stragglers. No more Chevra Shass - in fact no more shass - in Tredegar or Llanelli or any of the other places. No more shass indeed in Swansea, whose Beth Hamedrash was disbanded and its fine Hebrew library dispatched to Israel.

The inhabitants of the valleys minus their shass, made their way to the 'big city,' Cardiff. Newport which has always kept itself pretty much to itself, has suffered great attrition in recent years, and the oldest and proudest Welsh community, Swansea, is going the same way. Despite valiant efforts notably by that giant among communal leaders, Oscar Benjamin, and the ladies of the community, numbers are dwindling. Not a single marriageable Jewish boy or girl is left in the town.

And Cardiff itself, with some 2,200-2,500 Jews, is having its problems, Jewishly

speaking. First of all, there is, like everywhere else, the attrition of

inter-marriage. And the move from the valleys into Cardiff has not stopped there

and there is steady haemorrhage London-ward, particularly of the young for whom

the town has little to offer (the Jewish element in the University on the whole

keeps aloof). There is indeed a youth club under synagogue auspices, but it has

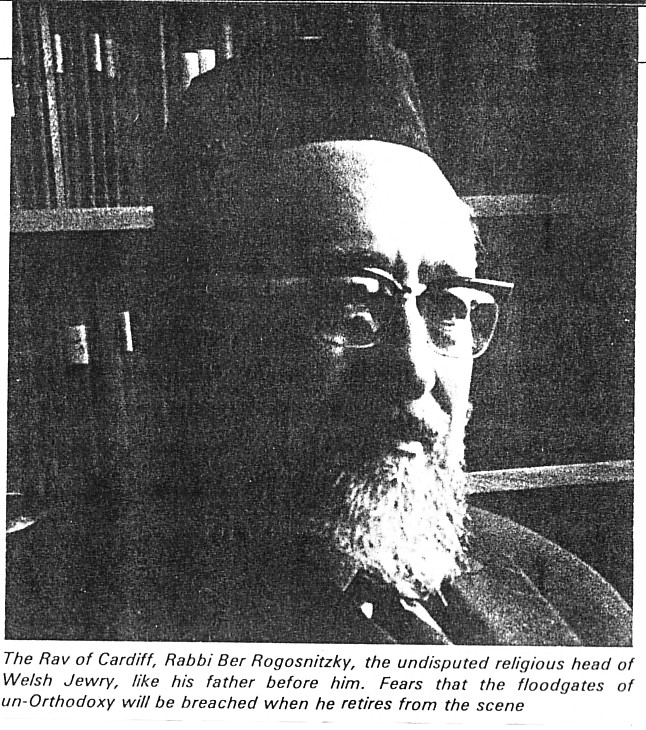

had its troubles, and, in the opinion of the Rav of Cardiff, Rabbi Ber

Rogosnitzky, "it has nothing to do with yiddishkeit, it is just for dances and

the like." He would admit though that it's better than nothing.

A kindergarten is run in the Penylan synagogue. Attempts to start a full-blown Jewish day school failed for lack of support. Cardiff has some reputation in the Jewish world outside of being a highly Orthodox community, and it is true that it comprises a nucleus of strictly observant families, estimated by Rabbi Rogonittzky as about a dozen in number, while thirty or so are 'officially shomre shabbat.

Their undoubted leader is Tredegar-born Norman Cohen, whose charming wife is a sister-in-law of the late Rabbi Kopul Rosen. Mr Cohen is the senior warden of the Penylan Synagogue and de facto lay leader of the Cardiff United Synagogue - 'United' because it represents the merger of three original constituents, but united also against the inroads of the Reform congregation (the New Synagogue, not to be confused with the former New Congregation, so called to distinguish it from the 'englisher shul' above mentioned).

Established in 1948, the New Synagogue now contains about 150 families, including a goodly number of German Jews. It also acts as a focus for people who are denies membership of the orthodox community, in Cardiff or elsewhere in Wales, because they have married 'out' or suffer some other religious disability in Orthodox eyes. Their rabbi from its inception has been the German-born Rabbi D. L. Graf, an enthusiastic shepherd who places particular emphasis on good relations with the outside world.

Notable among the observant section is Mr Lewis Hamburg as well as 'Jimmy' Samuel, recorder of the affairs of Cardiff for the 'JC' for over fifty years. Their attachment to tradition extends to loyalty to the handsome synagogue in Cathedral Road, which most of the community has abandoned for the more salubrious airs of Penylan and Cyncoed up on the hill. The Penylan Synagogue, with its large communal hall donated by the late Harry Sherman, the Maecenas of Cardiff Jewry, was opened in 1955, and looks very much a child of its age. In this case, new is definitely not better.

The ecclesiastical head of the Cardiff community, recognised as such by the civil authorities, is the Rav, who has served the community since 1945 (and his father before him from 1939). He is a man of strong principle - too strong for some, who saw his adherence to the Shulchan Aruch as too rigid. Behind and beyond his unbending principles beats a warm human heart, disciplined by an iron sense of duty, which he sees as the preservation of Orthodoxy in Cardiff, and elsewhere in Wales if they would let him, to his last breath.

It is this sense of duty that decided him, in face of strong temptation, to refuse the Chief Rabbi's invitation to join the London Beth Din when the learned Dayan Abramsky retired to Israel some 20 years ago.

It is the institution of the Rav, and the personality of the incumbent, that are largely responsible for Cardiff's reputation for Orthodoxy. He fears, and his fears are shared by many, that the floodgates against un-orthodoxy will be breached when he retires.

The 'greeners' have long since departed from the green valleys. They left behind a way of life sufficiently distinct from the general Anglo-Jewish pattern to add some much-needed colour and individuality. This way of life is now threatened with extinction. I propose the formation of a Welsh Jewry Preservation Society.

© Jewish Chronicle

Jewish Communities & Congregations in Wales home page

Page created: 9 November 2003

Page most recently amended or reformatted: 5 April 2016

Explanation of Terms | About JCR-UK | JCR-UK home page

Contact JCR-UK Webmaster:

[email protected]

Terms and Conditions, Licenses and Restrictions for the use of this website:

This website is

owned by JewishGen and the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain. All

material found herein is owned by or licensed to us. You may view, download, and

print material from this site only for your own personal use. You may not post

material from this site on another website without our consent. You may not

transmit or distribute material from this website to others. You may not use

this website or information found at this site for any commercial purpose.