|

|

|

[Page 201]

52°48' 28°00'

Translated by Jerrold Landau

|

|

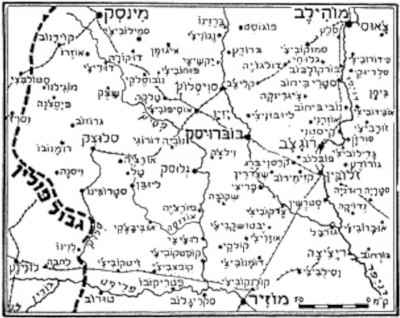

| [Note: Area of Lyuban. Bobruysk is the bold type city in the center. Minsk (on the left) and Mohilev (on the right) are the bold type cities at the top. Mozyr is the bold type city at the bottom. Slutsk is shown west and slightly south of Bobruysk, and Lyuban southeast of Slutsk.] |

Our small town was the estate of the Prince Wittgenstein. In earlier times, we would pay a set tax to him, each person in accordance with his property. However, twenty years ago, an official of the overseer of the prince's property came to us and harshly demanded that each of us should pay double. A few residents of the town did not with to obey his words; however most of the residents, out of fear, signed the book indicating that they agree to pay the double tax, as was demanded of them. However, later they regretted that they did this. So-and-so the expert [1] wrote requests to lower and higher ministers. He also traveled to Minsk and entered into negotiations with lawyers. The official did not accept the requests, and insisted that they pay double.

The years passed, and it is now twenty years. A few days ago, the Pristav (Police Chief) of Hlusk (Glusk) came and informed us that a final decision has been reached, and that we are required to pay the entire tax that was due over the past twenty years, the sum of 2,000 silver rubles. We were told that if the sum was not paid, our houses would be sold. Each of us had to pay 40 or 50 rubles or more. From where would we obtain the money? We were given a term of thirty days. The situation is bitter and difficult.

Translator's footnote

by Rachel Feigenberg

Translated by Jerrold Landau

During the 1890s, Lyuban was a far off corner at the edge of the bogs of Pinsk, surrounded by forests and ponds. A distance of more than 100 verst (and old Russian unit of measure) over poor roads separated it from the nearest train station. Nevertheless, even at that time, this small town displayed an exceptional vitality as a creative and working Jewish settlement. It provided its wares to larger cities of the region.

Lyuban was well known for its fine carpentry products, especially chairs. The regional capital of Bobruysk and its environs were a safe market for these.

Lyuban fattened ducks for export. These were sold in the choice marketplace of Bobruysk.

The residents of Lyuban fried duck fat for the Passover holiday. This won acclaim throughout the region.

The town also had a primitive manufacturing enterprise for Sabbath candles, which were sold locally as well as in nearby communities.

We should not neglect to mention the home made products of this sort, such as the braided havdalah candles[1] made of appealing colors, which were home produced by Reb Yedidya the teacher. These were works of fine craftsmanship with an expert religious-popular motif. They were popular with the surrounding communities as presents for homes and families.

Similarly, there were two brothers who conducted an enterprise for the manufacture of pipes. These pipes were of fine form and easy to use.

These handcrafted products of Lyuban had a guaranteed market among the farmers of the nearby villages. The merchants of Bobruysk served as the middlemen and distributors.

Traditional and isolated Lyuban of those days also supplied domestics who were expert at home economics. The notables and rich people of Bobruysk valued their services. They paid appropriate salaries and also provided nice gifts. A girl from Lyuban served Jewish homes in the city faithfully and honorably. The members of her community honored her as well when she returned home after several years with her sack of money – i.e. her dowry – in her hand, as well as a large suitcase of clothing and linens to enhance her parents home.

Lyuban also supplied workers for the estate farms of the region during the harvest season.

Lyuban, isolated between forests and bogs with tortuous roadways – this Lyuban of the 1890s, kept mainly to itself. During the days of fairs, its residents only reached the markets of the cities and towns

[Page 202]

of the region. They worked and conducted business there, and then they returned to their homes and families. The entire town was enwrapped in its communal and local bounds.

During those days, there was only one Jew of Lyuban who was so brazen as to break forth from the bounds of the town. This was the pampered young man Nachum Epstein – my maternal grandfather – who was an only child. By his luck, when he was a youth, he once hid in the attic. After many difficulties and attempts, he managed to construct an apparatus for the grinding of pepper that he gave to his mother as a present. From then on, he began to regard himself as an inventor of grinding equipment. To this end, he left his home and his parents, and wandered throughout the cities of Ukraine – which had the most important mills of Russia – where he attempted to introduce his inventions. For this purpose, he entered into imaginary business deals and went into debt until he was forced to work hard in the field of teaching in order to pay of his debts.

He repeated this chain of events several times until he ended up in Odessa. Only there did he abandon his milling machines. He dedicated himself to teaching religious subjects. Rich Jews hired him to teach these subjects to their children, over and above their general education.

Then came them time for his family as well to jump forth from the bounds of Lyuban. They left the town in the summer of 1876, and did not return again. They left there only their eldest daughter, who was married to the son of the local rabbi. This was my mother.

This single emigration did not have any influence on the Jews of Lyuban of the time. They remained closed off and shut in within the bounds of their town, as was usual.

As well, very few people came to the town from outside.

Sometimes a Maggid (itinerant preacher) came to deliver his lecture on the Sabbath. A rickety wagon laden with wandering beggars would unload in the synagogue courtyard, and the group of beggars, men women and children, would spread through the town to solicit donations.

At times the town would awaken from its slumber by the arrival of Dr. Schildkraut, who was specially invited from the city of Slutsk to tend to a seriously ill person. At such a time, the entire community of Lyuban would wait on the street for the arrival of the young doctor of Slutsk, who loved to joke and jest as the Jews asked him for cures for their many ailments.

At times, Lyuban would hear the sound of joyous bells, when the splendid caravan of the wealthy area landowner would pass through. His estate included the civic jurisdiction of Lyuban. At that time, the Jews of the town would stand at the doors of their homes, overtaken by submission and reverence. They would look at his splendid chariot harnessed to three pairs of horses, with thin backs and beautiful decorative saddles. The driver, wearing a purple cloak, would drive the chariot while standing. The entire sight instilled honor for his high position. To the residents of the town, this appearance of the poretz (landowner) was like a wonderful theatrical performance. They did not move from their places until the sound of the bells of the chariot could no longer be heard. Even the next day, the children of the town would tell stories of this splendorous appearance of the landowner and his “gentile” frivolousness.

Then, the town would return to its somnolence, frozen in its usual tradition.

From time to time, there would be a wedding in Lyuban. A Lyuban wedding in those days would be an experience and cause for joy for the local residents, particularly the women, for the task of making the bride happy with dancing was entirely in their hands. For dancing with women was forbidden to the men.

The children, who were uninvited guests, enjoyed the wedding to an even greater degree. They would always make a great deal of noise and shout at the time of the festive procession through of the couple through the streets. They were also given the privilege of holding up the poles of the chuppa (marriage canopy) in the courtyard of the synagogue. Their mischievous joy would be all the greater if the wedding was delayed due to a dispute between the in-laws over the dowry.

At such a time, the children of the town would be awake until very late in the night, along with the adults. At times, the dispute between the sides would last for many hours. Sometimes, it would even get more serious as midnight approached, and the bride and groom still remained in their fast[2].

Then they would call the wife of the rich person of the town, who was very meticulous with the mitzvah (commandment) of facilitating weddings (hachnasat kallah). She was Sheina Leah Moshe Neshes, a small, thin woman with a wrinkled face; however with blue eyes that sparkled with an eternal fire.

She would be wearing her weekday clothing, with a large embroidered scarf over her shoulders. This was a sign that she was not invited to the wedding as a guest, but rather as an arbitrator, judge, and facilitator of compromise. At such a time, before she left her home, she did not forget to don her earrings that were set with precious stones, which testified to her high rank among the wealthy residents of the area. These also testified to the social status of her husband Moshe Neshes, who was already far removed from the small scale weddings of forlorn and parochial Lyuban, for his eyes were turned to the forestry industry, to great riches, and upward mobility.

Indeed, the diminutive Sheina Leah, with her sparkling earrings, would hold influence over the disputing in-laws with her appearance alone. Immediately, the fervor of the dispute would calm, since both sides were already weary from the useless dispute. After a short practical deliberation conducted by Sheina Leah, the well-to-do woman of the city, they would reach a compromise. In accordance with her command, they would bring a pen, ink, and a piece of paper. She would write a promissory note, witnessed by herself, testifying that those signing the note would fulfil their obligations.

After the note was signed, the noise and rejoicing resumed. The wedding procession would then proceed on its way towards the synagogue courtyard. Everyone would be amazed that the young children were awake all night. They would accompany the celebrating couple with rapturous joy. They would hold lit paper lanterns in their hands, as they were wont to do each evening as they returned from their cheders in the darkness of the streets of the town.

After such an important communal event, Lyuban would return to its mundane life, with great boredom. A cow that was late in following its flock to pasture would lie crouched down for an entire day, along with an emaciated dog whose strength was exhausted due to hunger. Below them, a filthy hog, which had escaped from the streets of the gentiles, would crouch down. Yakim, the drunk from the gentile settlement on the outskirts of town would sleep innocently in the middle of the street, and nobody would move him. He did not disturb anybody, for they were all caught up with the worry of their livelihoods.

The town was poor, but the people were not starving for bread. The Jews of Lyuban of those days earned their livelihoods for the most part from the large vegetable gardens that they kept near their homes; from the produce of their milk cows that were kept in a creaky, cracked barn; and from their two or three laying hens

[Page 203]

who toiled for days on end in the garbage heaps in the streets and the courtyards in search of morsels of food. They also ate the kitchen leftovers of the dairy and vegetable dishes of the weekday fare. Meat and fish were only eaten on the Sabbath.

There were also residents of town who lacked those natural sources of livelihood. These included weak people, including lonely elderly people. The community looked after such people. Aside from two pious women of the older generation who went about from door to door on Thursdays with sacks over their backs and flasks in their hands to collect something for the Sabbath meals of the poor, there was also an organization “Matan Baseter” (“Discreet Giving”) to support the poor in an honorable fashion.

The residents of Lyuban of that time knew want and lack when they required cash for purchasing clothing, shoes, and work implements, for repairing their dwellings, and particularly for redeeming their sons from army service and providing dowries for their daughters.

Working Lyuban was used to putting forth constant, diligent effort, for it always was seeking out its narrow sources of livelihood, and therefore was frozen due to the expenditure of energy.

This was the Lyuban of days gone by, when the Jews of the town did not even have their own cemetery in which to bury their dead. A heavy farmer's wagon, hitched to muzzled horses, carried the dead Lyubanite along muddy roads to bury him in the cemetery of the community of Slutsk.

This was still before the row of stores was built, which uglified the beautiful Town Square. At that time, satyrs[3] still sang danced at night in the “Cold” synagogue[4], and the good wife of Mota the smith would chase away any ailment and evil visitation with her wonderful incantations.

This was the innocent Lyuban, the Lyuban that believed in G-d and Satan together.

However, at the threshold of the 20th century, everything changed almost at once. New times came. News reached Lyuban that a railway line would be built nearby. Merchants and industrialists from among the Jews of Minsk had already begun building the line to connect the Bobruysk road with the man railway that ran between the eastern and western parts of the country. They designated the new station next to that road, which was called “Old Ways”.

News faces appeared in town. Jews of stature, wearing fur clothing with splendid krakol hats arrived. They settled in town as permanent guests, and were involved in the businesses of the towns of the region. They were generous. They fixed the roof of the synagogue. They gave the rabbi of the town unusually large gifts of money at festival times, and they donated generously to the poor of the community.

Nevertheless, the Jews of Lyuban did not rejoice at these new situations that they had been blessed with.

At the same time, towards the end of the 1890s, the residents of Lyuban did not feel at home. The town moved, became uprooted, and Jews streamed, as they did from all of the settlements of the area, towards the desirable shore that was called America. Lyuban was emptied of its younger residents. Only people of the older generation remained in town. These people did not have the energy for the long journey abroad. The mothers and children who were set to emigrate also were among them[5].

These people were joyous.

Most of the women were already called “Americans” – a very honorable title. When the wagon drivers returned from the cities of the area, these women gathered around in order to received their large bundles of letters and valuable bank statements.

Money flowed into the town via these letters.

Among the noisy stream of prospective emigrants in Lyuban at that time, there were also some “Returned Americans”, who were full of disgrace and perplexity. You could recognize them by their sparkling clothing. Such a “returnee” would bring with him a few hundred dollars. Using the double amount of Russian rubles that he received in exchanged, he would open a store in the city. He and his family would support themselves in this manner for a year or two, and then he would be ready to go again.

There were those who tried their luck in this manner two or three times. The money that they earned from the backbreaking work in the sweatshops of America of those days was dedicated to an attempt to ensure that they would not have to emigrate with their entire family. However, the struggle was for naught.

The young women of Lyuban ceased serving as maids in the homes of the wealthy people of Bobruysk. They also stopped hiring themselves out as harvesters in the local farms. The eyes of everyone looked across the ocean.

Every local worker and artisan was material for emigration. The sweatshops of America of that time devoured the town with a wide-open mouth.

Despite this, Jews remained in Lyuban, and a new generation arose. This was the generation of the revolution (the Russian revolution of 1917), but we don't know much about the lives of the people of that generation.

We only know the frightful fact that, during the stormy years of the revolution, the residents of Lyuban drank from the cup of agony along with all other Jewish communities in that land. The murderous gangs of Balachovich, who perpetrated atrocities in the Jewish communities of the region, slaughtered approximately thirty people in Lyuban, parents and children.

Only very few of the youth of Lyuban of that era reached the shores of the Land of Israel during the 1920s.

In 1942, the Jews of Lyuban were murdered – men, women, and children. This was a complete annihilation by the German murderers, with the decisive participation of the local murderers from among the gentiles of the region. These treacherous people took revenge against the local police and the Jews, for they regarded the Jews as their loyal servants.

They killed the Jews with cruel and unusual deaths, just as was done to the rest of the millions of our people.

Translator's footnotes

by Zalman Epstein[a]

(One of the personalities of Lyuban)

Translated by Jerrold Landau

A great and valuable change took place in my life. I had waited eagerly for this change, and it was very precious and honorable in my eyes, for it would uplift me and place me on the seat of honor. This was that I left the teacher of young children and entered the cheder of Reb Yaakov Elya…

Rabbi Yaakov Elya! Though you did not know of him or his greatness, I knew him very well. I know that he was the choicest of teachers in our town, and his good name was known throughout the city and its environs. The best of the children would be his lot. I know that it was a special privilege for me that I was able to join his cheder and be numbered among his students. All of the students were older than I in years, and they were already studying Gemara and Tosafot (a commentary on the Gemara). A few of them already put on tefillin [1], and I was a young child of eight years…My former friends still remained with the teacher of young children for some time. Only I was raised up and merited to be accepted by Reb Yaakov Elya… On what account? Because, I, Shlomo the son of the Elkoshite, was a good and pleasant boy, a boy with fine talents, diligent in my studies, and finding favor with all that saw me… I could now look down disparagingly at the young children who remained in their lowliness in the cheder where I had studied up until this time. These were my friends in days gone by, but what about now? I no longer have anything in common with them! They would still sing “mahapach pashta”[2] each winter, recite their prayers in the cheder morning and afternoon, with their rebbe standing over them and guarding their mouths. I would worship in the Beis Midrash along with the adults. I was free in my soul, for an respected teacher such as Reb Yaakov Elya would not concern himself with such trivial matters; he would only care about teaching the students, for that is the main thing.

When I recall the images of my childhood, the portrait of Reb Yaakov Elya my teacher stands before me as if alive, with his thin face, his shriveled cheeks, his long peyos, and his tallit katan (four cornered fringed garment) with its long tzitzit.

To me, how dear is this portrait! How much light and warmth did he instill in the hearts of his young students, the young of the flock, who surrounded him! Oh, how he knew how to win over the hearts of the children with words of lore and ancient commentaries… On Thusdays, the rebbe would sit with his group of students, reviewing their lessons that they had studied during the week. The Gemara that they had studied that week, you should know, was difficult, extremely difficult. The sea of the Talmud boils like a cooking pot, it builds up and is torn down, asks and answers. Reb Yaakov Elya worked very hard during the week, many drops of sweat dripped from his face, until he succeeded in imparting understanding to his students, and guiding them in peace through this storming sea. His work was not in vain. This young child, sitting at the edge of the table, with the face of a cherub, white, soft and pure like the heavens, with the eyes of a dove, long peyos, a forehead as smooth as small, with his small hat covering the top of his head, was sitting bent over the large Gemara that was in front of him, chanting with his thin, pleasant voice the discourses of the Talmud… It is now the time of the exam, to see if his rebbe succeeded in his efforts. From the first glance it was possible to discern that both the rebbe and the student were satisfied, and that everything will work out properly. With a joyous face, a strong voice, with emotion and melody, this young, tender child will go along his way with confidence. He will not stumble, and his tongue will not be heavy. The words of the Gemara, interwoven with Rashi 's commentary, were uttered by the mouth of the child as if alive, enlightening, and joyous, and would hit their mark. This entire time, the rebbe would be sitting opposite his student, and would listen with full concentration to every utterance… A faint smile was on his lips, and rays of joy sparkled from his eyes. On occasion, when the child would stumble for a small moment, and become perplexed because he did not find sufficient words to explain the concept fully, Reb Yaakov Elya would utter two or three words, seemingly unintentionally, and the child would be encouraged and would get back on track… This would continue until, praised be G-d, the lesson would end and the child would leave in peace, in an exalted manner. The face of the child was burning from joy and internal and external emotion. “Rebbe, did I know the Gemara today?” the child would say, half asking and half making an assertion about which there was no doubt. “You knew, you knew, my son! You are a good boy, a very good boy”, the rebbe would answer, holding the cheeks of the child with love. Both of them were happy. The child was happy because he would be honored by his friends, and also because his father would be happy to hear about the praises that Reb Yaakov Elya gave to the child. But why was Reb Yaakov Elya so happy? Do you know the source of this joy? He was so happy when he saw that the divine labor was not for naught, he was happy to see that his sapling was bearing praiseworthy fruit. This impoverished man could forget about his poverty for a moment, and he could take joy in his love for his young student, in whom he saw greatness, and foresaw that he would be a rabbi of the Jewish people. For he, Reb Yaakov Elya would not receive the reward if this child would wax great and be the first among the greats. He would not be freed from all of his difficulties for this, and he would not receive a monetary reward from the parents, for they were also very poor. He loved this child with a love that was not dependent on material reward. He loved him because he was his student, because he was a good an pleasant boy, he loved him as a father loves a child…

You must not forget that this day was Thursday, and Reb Yaakov Elya did not have sufficient money for the many expenditures needed for the Sabbath. At evening when he returned home, his wife greeted him with her usual request of Thursday: to give her some money so that she can prepare for the Sabbath. Reb Yaakov Elya answered her in a vague manner, for he was afraid to reveal the truth to her. Finally, when he was forced to tell it as it was, he would tell her with a low voice and eyes towards the ground that he had no money at the time, but tomorrow… His wife chastised him and yelled that tomorrow, he would not have enough time to purchase flour, to kneed and bake. Reb Yaakov Elya stood and listened, but had no answer. His wife continued to storm on and said: “Why do you stand as a tree stump and be silent? Go to one of the “householders” and request the tuition money…” She did not know that all of the householders had already paid more than was owing at the time.

[Page 205]

His wife cried out loudly, “I do not know, I will leave you the children to do with them as you please, and as for me, if I am to be lost, I am to be lost”[3].

Reb Yaakov Elya could not bear her words anymore, and he went out… Where could he go, who could help him?… To whom can he go for help in his difficult straits…Perhaps to the wife of the Elkoshite?

Suddenly, the door opened, and here he was in our home… My mother, the children, including me, and two or three other acquaintances of ours were sitting around the long table. Without grace, with stumbling feet, Reb Yaakov Elya approached the table. My mother asked him to sit down, but he continued standing dejectedly… Several minutes passed in silence. Those gathered around, particularly the children, look at him in astonishment… Finally my mother asked him: “What is it, Reb Yaakov Elya? Why did you come?” “I have nothing, I have nothing” muttered the poor man, and he stammered to my mother that he has no provisions for the Sabbath, and he does not know how to extricate himself from his difficult situation…

Translator's footnotes

Original footnote:

by Tzvi Asaf

(His character)

|

|

| Rabbi Nechemya Yerushalmi (Jeruzalimski) |

One of the well-liked personalities who is still remembered by Lyuban natives with love and reverence was Rabbi Nechemya Yerushalmi of blessed memory.

He was born in Novogrudok in the year 5613 (1853), and was an only child. His father was an expert scholar, and was close to the Gaon Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor[1] of holy blessed memory, who served at the time in Novogrudok.

His talents were evident already in his youth. He studied Torah diligently in well-known Yeshivas, and was ordained by the Gaon Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan and other greats of the generation. His Torah novellae were printed in the commentary to the Mishnaic Order of “Nashim”[2] that was published by the “Ram” publishing house.

They loved him and respected him even though he was strong willed, and conducted his rabbinate with a high hand. His intelligence and his many activities in communal affairs made gave him renown, and people would come to him for judgement from far away. Even Christians would come.

Czarist government officials, and later on Polish government representatives (during the First World War) took heed of him. He appeared before them without fear on behalf of his community.

By nature, he pursued peace. He was very hospitable with guests. He was honored and appreciated by all segments of his community. The youth especially found in him an enthusiastic spokesman. He loved them so much that he organized a Sabbath prayer quorum (minyan) in his home especially for the youth. He believed in their traditional education, and would say: “A Lyubaner Bundevetz [3], if a pair of tefillin fall down near him, he would give them a kiss.”

The youth of Lyuban were Zionistic, even though most of them studied in Yeshivas. Lyuban excelled above all the towns of the area in the number of students who went to study in far off Yeshivas.

All his life, the rabbi longed to make aliya and settle in the Land of Israel. He was fortunate that, in his old age, he succeeded in coming to the Land. He arrived in the year 5682 (1912), and settled in Jerusalem, where his son-in-law Rabbi Simcha Asaf already lived.

He held the new settlement in esteem, and played a part in organizing “Knesset Yisrael”. He did not follow after the isolationist rabbis, despite their pressure upon him[4].

He would explain the situation as follows: “It is possible that the chareidim are correct in their isolationist stand, for they are concerned about the education of their children and are concerned lest they break free. However my children (he refers here to the youth who grew up near him) already are part of those circles – and I cannot separate from them.”

He would look out for the chalutzim (Zionist pioneers) in Jerusalem. He would especially keep in touch with workers' kitchen and members of the work group to ensure that kashruth was kept. He would appear on Sabbaths at every workers' gathering in Jerusalem, with his full rabbinical garb including his cylinder (rabbinical hat) and flowing white beard. His appearance was sufficient to ensure that they would stop smoking[5], for he conducted himself pleasantly, and everyone respected him.

Once when I was on route by bicycle to the printing house in Tel Aviv to give over corrections to one of the books, I saw him. I approached him. He was happy to meet me and extended his hand. I said to him: “Rabbi, my hands are dirty.”

He asked “Dirty from what?”

“From work,” I answered.

He said: “Work is never dirty, give me your hand.”

In the midst of the conversation, he said: “I like Tel Aviv, with its new settlement. Here, there are proud Jews who are building up the land, and the stores are closed on the Sabbath.. But in Jerusalem with its Tzadikim - and we cannot imagine their great piety. In truth, the Orthodox have made a great mistake. I refer to

[Page 206]

how they wake up with G-d, and go to sleep with G-d, while the Apikorsim (heretics) are around 24 hours a day. However, this is not correct, for you are dear Jews, very dear Jews, despite the fact that you trample on the Torah with the soul of your foot.”

His will is also very interesting. It also is true to his path:

…“C. Immediately after my death, the society for Hachnasat Orchim (providing for guests), the organization for Sabbath observance, and the funds for the building of Jerusalem, the Beis Midrash, Hachnasat Orchim and my friends in the Talmud Torah, should be informed that they should be careful to fulfil my request. For I am a member of their group, and they must fulfil the wishes of the departed. They should fulfil the commandment of “skila”[6] with my body. It is good that I receive pain and embarrassment in this world, so that I should not suffer in the World To Come, for my sins are always before me, and I am not exempt from the law of the four death penalties. Therefore I accept upon myself the most stringent of them.

D. No embellishments should be made in the eulogies, for every embellishment contains some exaggeration, and this causes a punishment. I do not wished to incur punishment due to any of the eulogizers. They should only say that he served in the rabbinate for forty years. If the eulogizers cannot see any benefit in discoursing on Sabbath observance or the love of peace, etc., it would be best if they do not eulogize me at all. If they can see benefit in doing so, then I permit them to deliver eulogies for me in public, and if not, I request that they do not eulogize me. They should weigh every word carefully, to ensure that it is has benefit for the audience.

Those who occupy themselves with matters of the funeral and burial should inform the workers' kitchen and the work group that if they wish, they should take precedence to anyone[7], for I toiled greatly to improve their spiritual life. If they will grant me kindness and recognize their debt, I grant them precedence. If not, those storeowners and barbers with whom I worked to ensure that their stores would close on the Sabbath, should take precedence in dealing with my bier, and they should recognize their obligation. If even these do not recognize their obligation, then you should follow the custom that is followed in this place.”

He died suddenly. On the night of the 24th of Shvat, 5690 (1930), he was sitting and studying Torah until 9:00 p.m., and then he went to bed. He woke up with pains in his heart at 10:30, and his soul left him in purity a short time thereafter. May his memory be blessed.

Translator's footnotes

Translated by Jerrold Landau

|

He was the son of Yehuda Zeev the merchant, and Feiga the daughter of Tzvi Yaakov Epstein of Bobruysk. He was born in Lyuban on the 9th of Tammuz 5649 (1888).

He received a traditional education in cheder, and in the Yeshiva of Slutsk from Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, and in the Yeshiva of Telz (from the years 5665-5668, 1905-1908) from Rabbi Eliezer Gordon (Reb Leizer Telzer). He received his ordination. He served as a rabbi in Lyuban in the years 5670-5671 (1910-1911).

From the years 5674-79 (1914-19), he served as the Rosh Yeshiva of the Yeshiva of Odessa that was founded by Rabbi Chaim Chernovitz (Rav Tzair). He began his scientific-literary work in Odessa, and published his first articles in “Hashiloach” and “Reshumot”. He had already become a Zionist in the Yeshiva of Telz, and there he worked to disseminate the Zionist idea. In Odessa, he joined the Zionist movement, and was elected as a member of the Zionist council of the city.

He married Chana, the daughter of Rabbi Nechemya Jeruzalimski (a rabbi in Semezhevo and Lyuban, who made aliya to the Land of Israel in his old age). He made aliya at the end of 1921, and was appointed as a teacher of Talmud in the Mizrachi seminary in Jerusalem. He published many investigations and books on classroom surveys in Israel, teaching methodologies, court proceedings, and relations between Torah centers in the Diaspora and Israel.

At the time of the founding of the Hebrew University (5685 – 1925), he was appointed as a lecturer, and later a professor in Gaonic and rabbinic literature[1].

He was one of the veteran Mizrachi activists, and he represented Mizrachi in the national council and various meetings. He was a member of the honorary court of the World Zionist Organization, as well as the honorary court of Mizrachi. He served as the chairman of the honorary court of the teacher's union of Israel, as a member of the advisory committee for the Hebrew Organization for Research of the Land of Israel and its Antiquities, as the vice chairman of the educational committee, as a member of the active council of the Hebrew University and its rector, as the chairman of the “Awakeners of the Slumbering” organization, as a member of the council for the Rechavia neighborhood of Jerusalem, and as vice president of the B'nai Brith organization of the Land of Israel.

We cannot be too verbose regarding Rabbi Simcha Asaf. It is most unfortunate that he went to his eternal rest in his prime (at about age 64) in Jerusalem. He was indeed a Renaissance man, and he wore many crowns. He was an excellent writer and researcher. At the establishment of the State of Israel, he was appointed as one of the five first Judges of the Supreme Court of Jerusalem.

[Page 207]

As a researcher, he stood out because of his easy and pleasant style, and his clear explanations. He published important books during his life: “Sources on the History of Education in Israel,” “Punishments after the Closing of the Talmud,” “Court of Law and their Proceedings,” “Responsa of the Gaonim, and Excerpts of the Book of Judgement,” “An Anthology of the Letters of Rabbi Shmuel the son of Eli and his Generation,” “The Book of Documents of Rabbi Hai Gaon,” “From the Gaonic Literature,” “The Library of the Rishonim, ” “Responsa of the Gaonim from the Cambridge Library,” “In the Tents of Jacob,” “Sources and Research in Jewish History,” “The Book of Professions,” and others.

Writers and Hebrew readers were very pleased with his work “The People of the Book and the Book” (printed at first in one volume of the Reshumot anthology, and collected with additional material in his book “In the Tents of Jacob”) until this day, this serves as a reliable source for all of those who are seeking plentiful and valuable material

|

|

| The text was written by the writer Sh. Y. Agnon, and the engraving was by the graphicist Y. Shechter. |

[Page 208]

on the Hebrew book in ancient sources and in the eyes of the Rishonim and Acharonim. He left behind unfinished manuscripts and material for several books, including a book on “The Era of the Gaonim and its Literature.” He had hoped to finish these books shortly, and he promised to write his autobiography when he reached the age of seventy. He did not attain this age – and the song of his life was cut off in the middle.

I remember when he came to New York in the year 5711 (1951), and was hospitalized in the Mount Sinai Hospital. I visited him there, and I found in his room Professor Boaz Cohen and the researcher M. Lutzki. I was astonished to find Rabbi Simcha Asaf happy with life, and in a humorous mood. He discussed with me his two years of study in Minsk (5671-5673 – 1911-1913), the city of my birth. There he studied in the Kolel Avreichim [2]“Prushim.” He was also appointed by the chief rabbi, Rabbi Eliezer Rabinovitch, as a teacher in his home. He related to me his memories of personalities and well-known events from the time of my youth. His memory was wonderful, and his descriptions were full of minute details. Later, he told us jokes, so that the room was filled with waves of laughter. He was happy because the doctors had determined that he did not require surgery. Later, we learned from them the secret that the hardening of the liver has no cure at all.

By his nature, he was a man of action, and he fought for the Zionist idea. During his youth in the Yeshivas of Slutsk and Telz, he was very active in Zionist activities. He lectured and spoke, and entered into debates with representatives of Bund, the S. Z. (Socialist Zionists), and other disputants. Later, he became one of the leaders of Mizrachi, a position he held until the day of his death. He always took upon his shoulders public, educational, Torah and literary assignments. He expressed everything with exactness, order, faith, and joy, as is testified by his first name, Simcha[3].

Translator's footnotes

by Reb Moshe Gershon Finkelstein[a]

Translated by Jerrold Landau

|

|

| Reb Moshe Gershon and his wife Sara |

My maternal grandmother lived in the village of Kuzmichi, near Lyuban. Her name was Fruma Batya, and she had three brothers, Reb Tzvi Noach, Reb Efraim Yitzchak, and Reb Gedalya. They were all upright men. Their neighbors and all of their acquaintances respected them due to their vast knowledge of Talmud and their good heart. Reb Tzvi Noach lived in Kuzmichi, and Reb Efraim Yitzchak and Reb Gedalya lives in the vicinity of Lyuban. Reb Gedalya occupied himself with business, and he studied Torah when he was not busy with his work. They said of him that he knew the six orders of the Mishna by heart[1]. At the time of his old age, he gave over his business to his children and he occupied himself with Torah. His neighbors and all of his acquaintances regarded him as a holy man. When a bad incident occurred to any of them, they would go to Reb Gedalya to ask his advice and request his blessing. Being of good heart, he tried to fulfil their request, and became known as a wonder man. People came from near and far, and gave him no rest. He pleaded: “What do you see in me? I am as one of you, and if I am in trouble, I pray to G-d.” However, his words were of no avail. People begged him with bitter tears, and some also tried to honor him with monetary gifts, which he refused. When they advised him to give the money to charity, he told them to do so themselves, for “a mitzva is greater when done by a person himself than by an emissary.”[2] When he saw that the multitude of petitioners continued to grow, and that he could not free himself from them, he decided to leave his home and to go to his brother Reb Tzvi Noach in order to hide from his fans. That is what he did.

When he came to his brother and told him all that had happened to him, his brother said to him, “Live with me as long as you desire, and we will enjoy our brotherly company.” Reb Gedalya said to him, “You should certainly know, my brother, that I cannot accept my bread as a gift, so if you allow me to cut wood, to light the oven, and to care for your produce, I will live in your house.” Reb Tzvi Noach answered him, “You can do as you say, but do not push off my servant; let him also chop wood and watch over the produce.” After about half a year, people found out where Reb Gedalya was living, and they began to come to him in greater numbers than previously. Perforce, he made his peace with his lot, and no longer hid. Even the local farmers bothered him with their requests. One of the farmers came to him and said, “Do good for me, oh you man of mercy, sit in my wagon and traverse the length and depth of my field, so that my produce will grow.”

My grandmother Fruma Batya remained as a young widow with five children. She sustained herself and her children from her meager business, but when the time came to teach them Torah – and she was the only one in the town who had need of a teacher – she decided to raise calves. She would sell a calf every half year, and with the proceeds, she would be able to pay the tuition of the teacher that she hired from Lyuban. One summer when the flock was out at pasture, a wild animal came and preyed upon the calf of Fruma Batya specifically. When the time came to pay the teacher, she took two pillows and four Sabbath candlesticks, and went to her neighbor Frakof and said to him, “You of course know that my calf was torn up, so please lend me 20 rubles, and I will leave these objects as security.

[Page 209]

” Frakop said, “Leave these on the table” and he gave her 20 rubles. Approximately a half year later, Frakop took the pillows and candlesticks to her home. She asked him, “Why did you take the security at first, and now you are returning it?” He answered, “I did not take them from you, I only told you to put it on the table, so that you would not have to carry them yourself.”

How was the Lyuban cemetery founded? There were approximately 200 Jewish families living in the town, and they did not yet have a Jewish cemetery. They would bring the deceased to the cemetery in Slutsk, an entire day's journey. One of the residents of Lyuban moved to live in Bobruysk. In the home of Boaz Rabinovitch, the well-known rich man of Bobruysk, there was private rabbi, who taught him and his sons. That rabbi was very careful about distancing himself from the sin of the evil tongue, and therefore he desisted completely from speaking. His voice was only heard with regards to the study of Torah or prayer.

When he wished to express something, he would write down his request on a piece of paper. The Lyubanite who settled in Bobruysk told that rabbi that the Jews of Lyuban had no cemetery. One morning, when the residents of Lyuban entered the synagogue to worship the Shacharit (morning) service, the well-known rabbi of Boaz Rabinovitch was standing outside the synagogue with a note written in large letters: “It is urgently necessary to set up a cemetery near Lyuban so that they will not be forced to carry their deceased to a far off city.” After the morning service, he wrote another note: “I request that the leaders of the community remain in the synagogue for a meeting regarding the above mentioned matter.” My father-in-law, Reb Yaakov Chasid, who was one of them, promised the rabbi that they would act in accordance with his wishes. He told him that the poretz landowner of the town already set aside a plot of land from his estate for a Jewish cemetery, and all that was missing was 200 rubles to build a fence. The rabbi wrote an additional note: “I will not move from here until the required sum is raised.” The money was raised that very day, and the rabbi returned to his place.

After my marriage, I joined the Chevra Shas (Talmud Study Society) of Lyuban. The members of the society would split up the tractates of the Talmud among themselves. One would study the tractate of Berachot, a second Shabbat, etc. The teachers of young children would always choose the same tractate that they would be teaching to their students, and the rest of the members chose whatever tractate they desired. Most people did not jump to take the tractates from the Orders of Kodshim and Taharot [3]. These tractates only had three redeemers, Rabbi Nechemya Jeruzalimski, my father-in-law Reb Yaakov Chasid, and their friend Reb Halulenchik (the incense maker). These three made Torah their prime occupation. Each year on the holiday of Chanukah, all of the members would gather together for a general meeting where they divided up the tractates anew, and partake of a banquet.

During one of these meetings, I was elected as the gabbai (trustee) of the society. The tasks of the gabbai were to concern himself with all aspects of the society, to invite the members to the meeting, and to organize the banquet. All those who wished to join the society would turn to him, and the gabbai would present the names of the new candidates to the members. A few young people requested that I bring them in to the society, including one young person with a shaved beard. In my innocence, I discussed the names of the candidates with my father-in-law. “The shaved one is not fit to be a member of the Chevrat Shas, ” he told me in anger.

The days of Chanukah approached. The issues surrounding the meeting and the banquet had to be organized. I went to Feiga the baker and ordered wheat flour rolls in accordance with the number of attendees, and I also prepared fish. On the night of the meeting, all of the members came with the exception of Reb Binyamin Halulenchik, who felt that the study of Torah should take precedence over the banquet. Reb Nechemya turned to me and said: “I thought that Reb Binyamin would have come to the banquet this time, for is he not trampling[4] and you are the gabbai.” I took it upon myself to bring him against his will. Three young men assisted me in bringing Reb Binyamin. The entire assemblage greeted him with applause, and seated him next to the rabbi. I went to bring him his portion, but, alas, the roll had disappeared, and it was impossible to obtain another one. The rabbi said with laughter, “If we merit to have Reb Binyamin partake of the banquet, it is fine, provided that one of us forgoes his own portion.”

|

|

| The New Synagogue that was built after three splendid synagogues burnt down |

Translator's footnotes

Original footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Slutsk, Belarus

Slutsk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Apr 2025 by LA