[Pages 113-120]

Inside Rohatyn

by Chuna Yonas, Paris

Parties, Societies, Institutions

A Zionist society, known as the “Land of Israel League,” existed in Rohatyn prior to World War I. In 1917, a group initiative, led by Chanah Wabman, Pinia Spiegel, and Meir Lewenter, revived the League, which was then headquartered in the house of Buzio Bomze. The organization had 250 members. Many shtetl boys and girls attended league meetings. A number of young people also joined the academic association and the Zionist union “HaShomer”.

Nor were we backwards when it came to the matter of education. There was a Hebrew school. A Talmud Torah also existed before World War I. There were many houses of study, one large school and three little schoolrooms. Our large Beit Midrash (house of prayer and study) was particularly fine, with its beautiful decorative paintings. The building of the Beit Midrash was across from the old house of study. The Stratyner synagogue, behind Yudel-Mechel Sofer's house, was not far away. And across from that, the little Czortkower synagogue, between Zelig Nagelberg's and Boimrind's houses. There was also Reb Nathaniel's synagogue.

The local butcher shop was not far from Reb Nathaniel's synagogue. An artisan's guild also existed in our shtetl, headed by Michael Katz.

The large and beautiful Zionist library, run by the Zionist organization, should not be forgotten. It was a tradition that every Sabbath afternoon, a different person would read aloud from some writer's works. (One reader, Fischel Weiler, now lives in Tel-Aviv.)

We had good prayer leaders. It is enough to mention Yehonoson Rappaport, who in addition taught a chapter of Gemara every Friday night; Mordecai-Shmuel Harshowski; Reb Yosef Laks, the Kohen; the famous cantor and composer Moshe Zushes, of blessed memory, and Efraim Sternhel, who led prayers in the Stratyner synagogue.

All kinds of Jews of different parentage and station lived in Rohatyn, rich, poor, tradesmen, craftsmen, butchers, doctors, lawyers, unaccomplished intellectuals, Hasidim, misnagdim, hackney drivers, porters, village traders and peddlers. We were not lacking in poor people. In a word, Rohatyn was no different from any of the surrounding Jewish shtetls in Galicia.

Jewish children studied Torah fervently in cheder. The cheder in wintertime is especially etched in my memory. We would return home in the evening, each child bearing a lantern, with a lit wick inside. Our pride in possessing a lantern was great.

Performing Tashlich on Rosh Hashanah was a beautiful custom. I especially remember Chaim Teichman who used to return singing to the synagogue where he would dance on the tables.

Before World War I, the Zionist youth leaders organized a mandolin orchestra that played every year, on the eighteenth of August, beneath the windows of the local commissioners, mayors and other important people.

Let us remember those who stood out in the life of Rohatyn, such as our neighbors Aaron Winkler and Moshe Leder. The latter was a leather dealer and the owner of two houses. I remember him as an old man, sitting by the gate with his long-stem pipe. I also recall Shmuel Einstoss, whom we called “Shmuel, the merchant,” Eli Glazer and Avrum Ziff. We lived with Avrum Ziff. I grew up with my grandmother, Etel Banner. Yehoshua Ziff and his two sons-in-law, one, a schoolteacher, and the other, a coachman, lived in the same house. The Withoff family, who later moved to Lemberg, also lived there as did Shmelke Rokeach who made ornamental collars for prayr shawls and Yekel Brieftraeger, with his wife Lajcie, “the grandmother”.

In general, Rohatyn was considered an enlightened shtetl. It contained Hasidim and misnagdim. The latter had greater influence. They waged an unceasing struggle for influence over the local community. Alter Weidman was the head of the enlightened faction, and Efraim Sternfeld, of the religious one.

Rebbes and Rabbis

There were four camps of Jews in the shtetl, each one backing its own candidate for rabbi. This was in the time of the Russo-Japanese War, when the old rabbi of Rohatyn, Rabbi Natan Lewin, left the shtetl for Reisen (Rzeszow). Following his departure, there were many disputes surrounding the candidates seeking to occupy the position of the shtetl's new rabbi.

As I recall, the first dayan appointed in this period was the Strelisker Rabbi Meir-Shmuel Henge. After him, we had “one of our own” as rabbi, someone from Rohatyn. In his youth, he had worked for a lawyer as a scribe. In those days, no one in Rohatyn had acquired a typewriter, and the fine handwriting of the future Rabbi Spiegel served the lawyer well. Together with his old friend Shimon Teichman, he worked for the attorney Lipiner who was greatly pleased with his employees. It happened once that the lawyer returned from court to find his scribe, Spiegel, sitting in the office, and peeping out from beneath his shirt, the four fringes of his ritual undergarment. Lipiner told him, “You will have to make a decision; devote yourself to working for me or become a rabbi. Because sitting in my office with your fringes hanging out, this will not do.” Clearly, the young Spiegel chose the path of Torah and left the lawyer's office. For a year, this occurrence served the shtetl as a topic of discussion.

Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel was more worldly than pious and therefore had many followers in Rohatyn. During his term, there was also another dayan in the shtetl, Rabbi Meir Henge, who represented the more pious Jews. He was known as the Strelisker dayan. He spoke no foreign languages. On the eighteenth of August, Franz-Joseph's birthday, when they were obliged to greet the local commissioner, the two dayans would go together, but Rabbi Spiegel did all the talking as he spoke Polish, Ukrainian and German.

Our first Hungarian rabbi was the Grand Rabbi Eliezer Langner, a son-in-law of the Stratyner rebbe. Later, we had the son of the Stratyner Rebbe Yehudeh-Tzvi, may his memory be blessed among us, the Grand Rabbi Shlomo Langner.

Many Jews were arrested in 1915. The two dayans were set free. They appealed to the local commandant, Pogrebny, to use his influence to free those Jews held by the authorities. The commandant began speaking to the older dayan, the Strelisker dayan, Rabbi Meir-Shmuel Henge. As the older dayan could not understand him, however, he had no choice but to address the younger dayan, Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel.

Elections for the Austrian Parliament

In 1907 or 1908, elections were held for the Austrian Parliament. It little seemed, at first, that soldiers would have to fire on an angry crowd. The ballot boxes were located in the Jewish communal office, the headquarters of the Jewish parties, in the Beit Midrash. There were three Jewish candidates ––Breiter, a socialist, Dr. Reitzes from Zloczow, who was elected to represent Zloczow proper, and Rappaport, a lawyer from Lemberg. All three could by no means find lodging for the night in Rohatyn. Late at night, a Ukrainian lawyer, Babyuk, took them in, and they stayed over with him. It turned out that the local hotels had received an order from the commissioner not to rent them a room. They also had a hard time finding meals.

There was a Polish candidate, a certain Kowalewski, in whose election the authorities were interested. The Jews would not vote for him, however, preferring the Zionist candidate, Dr. Rappaport. Therefore, all kinds of tricks were employed. As the Polish candidate was led from the train station amidst a grand parade, the Jewish candidates were left on their own. Dr. Breiter and Dr. Reitzes had both also arrived at this time and had to wander through the shtetl on their own, having nowhere to go. The local commissioner arranged all of this.

In the middle of the election, the commissioner interrupted the voting. A few Poles were stationed by the ballot box to carry out the orders of the authorities. Hired Ukrainians searched every voter, making sure that they didn't have any additional ballots.

Dr. Reitzes, who was then already an elected deputy in Parliament, struggled energetically against these maneuvers. He rushed from the Zionist party's headquarters to the election headquarters and protested strongly before the commissioner against the violation of voters' rights. I remember, as if it were today, the way he addressed the commissioner in the informal second person, which made quite a strong impression. The Zionist youth weren't caught sleeping either and guarded, as they could, against the searching of voters. A militia encircled the building in which the ballot box was located. The commissioner would not let Dr. Reitzes into the building even though he was a deputy. In addition, he gave an order to the officer of the army unit that was stationed by the building to disperse the crowd by force. Of course, the first to flee were the little Jewish children, among whom I was to be found. And after us––the Jews who wanted to cast their votes.

Deportation to Russia

When the Russian Army took Rohatyn, in 1915, all Jews were driven out of the shtetl. In the middle of the night, all of the men were roused from their beds and sent away into the depths of Russia, to the province of Pezner. On Wednesday, the arrested Jews were driven into the local school in Babince. After sunset, we were lined up in rows, counted and ordered to march to Podwysokie. There we spent the night in an open field. In the early morning, we were once again lined up and counted and then marched still further, to Brzezany. Along the way, we were severely beaten. The first to receive a beating was Mendel Rotenberg. At midday, we came to Brzezany. We had to make our way on foot. We were led into the local barracks. At dusk, we were again ordered to go. We noticed that Velvel Weissbraun's eldest son, Moshe, had been arrested. We were then without strength. I was the youngest of those sent away.

Before our arrest, twenty-two community leaders had been taken, prominent men of the shtetl. They were commanded to compile a list of all the Jews in the area. Yankel Leiter found himself the leader of this group. They refused to carry out the order of the Russian authorities. Jews were therefore taken from their beds. Five hundred Jews were arrested in all, of whom only 350 survived. Over 150 died on the roads of Russia. A cholera epidemic had broken out among us.

The City Intelligentsia

Rohatyn was also a city in which an intelligentsia sprang from the native Jewish population––lawyers (Dr. Scharf and Dr. Weidman) and doctors (Dr. Stein, Dr. Lewenter, Dr. Hekel Weinstock and Dr. Chaika Kiesler). Meir Lewenter, the elder brother of Dr. Yitzchak Lewenter, both outspoken Zionists, was a contributor to the Lemberg “Togblatt.” There were many other strong intellectuals active in many realms of local life––the physician Dr. Stein, who was the city doctor, the local lawyer Dr. Kleinberg, a leader of the leftist “Poaley Zion” and also Dr. Alter, who, as a lawyer, undertook political defenses in the court of Rohatyn.

Time, which has run on since I left my shtetl in 1920, has done its work. I do not remember very much. Also, my efforts to survive under the German occupation of France sapped my strength. Twice the Germans had me in their hands, and each time, I managed to escape. From Paris I went to Grenoble where I joined the resistance movement and fought against the German occupation.

[Pages 118-120]

A Bundle of Memories

by Marcus Zin, Acre

Rohatyn was known in the Jewish world for its rabbis. Great learned men would have paid us to choose them as our rabbi. This high office was occupied by Rabbi Meir Glos and Rabbi Natan Lewin. Lewin, who later became a rabbi in Reisen (Rzeszow), was the father of Rabbi Ortsi (Aaron) Lewin who, apart from being a rabbi, was also a deputy in the Polish Sejm. Lewin's second son, Rabbi Yecheskiel Lewin, was the chief rabbi for the Lemberg district. In addition, there was the dayan and righteous teacher, Rabbi Yaakov Kovi-Schein, and later, the old dayan, Rabbi Shmuel Henge, or, as we called him, the Strelisker rabbi, and last but not least, Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel (even in his later years, he was still called “the young dayan”). Rabbi Spiegel also represented the Jewish population before the secular authorities.

I remember certain events that are characteristic of “the young dayan.” After the synagogue burnt down in 1915, he not only collected money to rebuild it but also rolled up his sleeves and helped clear away the half-burnt bricks from the wreck in order to begin transforming the ruins into a new building. His example inspired others, and many Jews helped in the rebuilding of the synagogue. The city valued the rabbi's achievement greatly and awarded him with a permanent seat of honor in the synagogue behind the lectern by the eastern wall… He was consequently given this honor in every holy place.

Rabbi Spiegel also gave ritual sanction to, and therefore was the inventor of, a way of keeping the ritual bath warm, even on the Sabbath. This ritual bath was renowned for its cleanliness, and even the impious used to use it, especially on early winter mornings. The surrounding shtetls later followed the example.

To the account of Rabbi Spiegel's achievements and initiatives must be added the establishment of the Talmud Torah, which provided a Jewish education to numerous children of Rohatyn, and the study of the “daily page” of Talmud, which he led. He served in deed and counsel with a warm word and substantial assistance over the course of his thirty years in the office.

After our Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel, in the few years before the war, Rabbi Mordecai Lipe Taumim held the position.

Among the Hasidic rebbes in our city was Rabbi Eliezerel, a man possessing all of the virtues, who didn't mix in city matters and was beloved by all the Jews. Later, Rabbi Shlomele of the Stratyner dynasty came to Rohatyn.

* * *

The Zionist movement in our city was organized and led by Elchanan Wachman, Pinchas Spiegel, Akiva Wagschall, Hersh Laterman, Lipa Mandel and others. They instilled in the youth a desire to go to the land of Israel. The leaders of the Zionist organization suffered enough at the hands of the Austrian government, but this did not keep them from undertaking their work.

* * *

After the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, Rohatyn was burned down when the Czar's army came to the city. In 1915, all of the Jewish men in the city were deported to Russia. Only Rabbi Spiegel was left behind. He became the father of every child in the city. He knew when to tell the mothers that their children had to begin putting on phylacteries, and he prepared the children to do so. I myself was one of those children…

In 1918, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed. The Ukrainians took power, then Poland, later the Bolsheviks, and finally, Poland again. For Jews, these times offered nothing but pain and suffering. Elchanan Wachman, the well-known Zionist ideologue, was severely beaten by hooligans. The blows left him permanently impaired; he saw everything double… He went young from the world.

|

|

The clearing of the ruins of the Great Synagogue and its restoration, after World War One

Pictured from the right: Yankel Leiter, Dudel Wald, Yosef Fidelbogen, Nachman Fidelbogen with his grandson in his arms, Moshe Shine (with the wheelbarrow,) Berish Hersh, Volvel Weissbraun, Yoel Granubiter, Abba Kartin, Ruven Brudbar, unknown, and two youths |

|

|

| The small, Russian Beis-Medresh (study-house) after World War One |

In 1921, the city was rebuilt and life normalized. Many unions were organized, political and professional, as well as assistance societies, Zionist organizations, “Hitachdut,” “Yad HaRotzim,” artisan guilds and others.

The Jewish landowners in Dusanow permitted the Jewish youth to practice farming (preparatory training) so that they could later immigrate to the land of Israel as pioneers. The Russians had burned the city's two houses of study, the synagogue, and the large Beit Midrash with its rich history. They had twice tried to set fire to this house of study, but the fire had not caught. People said that it was an act of God, and it stands to this day. So does the historic 600-year-old cemetery with the common grave from Chmielnicki's time.

* * *

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, many refugees came to Rohatyn. The city gave much assistance to the unfortunates. A committee was formed consisting of Pinia Spiegel, Dr. Goldschlag, who was vice-mayor, Akiva Wagschall, Lipa Mandel, Yisroel Gleicher, Dr. Zlatkes and our beloved Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel. They made sure the refugees had food to eat and a place to sleep.

In 1941, the war between Germany and Russia broke out. On Rosh Hashanah, Hitler's murderers entered our city and began annihilating the Jewish population.

[Pages 121-123]

Sounds of Home

by Dr. Natan Spiegel, Jerusalem

Translated by Binyamin Weiner

According to historians, Rohatyn was not a big city, when compared with others in its region. In 1912, Rohatyn had over 7,000 inhabitants, half of them Jewish. In 1941, there were 12,000, approximately 6,000 of them Jews. The murderous Nazis destroyed nearly the entire population.

But Rohatyn was more to me than the mere statistical number of its inhabitants. It was where my parents, family, and friends lived and perished. There I attended traditional cheder and school. There I experienced my first joys and sorrows. There the years of my childhood and youth passed by.

The material conditions of my upbringing were poor: a small and aged one-story house with a wooden floor, the walls of the hallways covered with mildew. It is no wonder then, that under these circumstances I contracted a kidney disease, and my sister, three years my younger, had a sickness that affected her sight. My brothers, Muah and Sami, years older than me, were exceptional for their good vision.

Despite these poor conditions, I have still preserved fond memories of childhood. This was no doubt due to the positive atmosphere that pervaded our house.

My father, may he rest in peace, a wise man and good of heart, was an expert embroiderer, and bore the responsibility of providing for his family and seeing to the education of his children.

Our mother was a “Jewish mother” in the very spirit of the ideal. Though her health was always poor, she looked after the well being of her children and husband. We loved her very much, and rejoiced in the wonderful, mutual affection that bound her to our father, a warm and heartfelt affection that was never clouded by the shadow of misunderstanding.

From my earliest childhood, I attended a traditional cheder. Despite its academic flaws, I still recall it lovingly as a

“small room, narrow and warm,

a fire within its stove,

where the Rabbi teaches alef-beis

to his little students.”

One of my teachers was Nahum Millstein. I remember him with love. His son Anshel was a dear friend of my youth. Anshel lives here in Israel now, in Ramat Gan.

I was especially gladdened when our big brother came to cheder, to take us, that is, my brother Sami and me, to the cinema. My father, as I recall, put up a whole crown for these expeditions. Three tickets cost 45 cents, and the remainder was devoted to the purchase of “shtulbriki,” “milkeh-soshard” (a heler got you one piece,) and balls of chocolate (liberkneidlech.) Such joy, such delight!

In 1912, when I was seven years old, I began attending a Polish elementary school, in addition to the cheder. Mrs. Tsirler, an excellent teacher, who later became the wife of Dr. Milgrum, the regional doctor, taught me there. She was a prominent woman, who employed a modern method of education, which was a rarity in those days.

I still guard the memories of a special possession, whose light made my heart tremble when I was still in elementary school. At the end of my second year of studies, I received a small book as a reward for my diligence. Two birds were drawn on the cover and the book itself contained several poems. Whenever I read them I was moved to tears. One song, for instance, went like this:

“Do not pursue the butterfly.

That which passes in an instant

Think it gone—

This is the secret of a peaceful life:

Do not pursue the butterfly.”

I held this book among my greatest treasures, and I lost it in the Second World War. I recall that during this same span of years our city passed frequently from hand to hand. Once we fell into Austrian hands, once into the hands of the Germans, and once into Russian hands. We were often compelled to hide in the basement, in times of shooting, when soldiers passed through our houses to plunder and desecrate.

During the Russian retreat, most of the Jewish houses were set on fire. The Jews had earlier fled to the outskirts of the city, and all night we watched as a pillar of fire played above the rooftops.

At dawn, we rushed, full of worry, to see if by chance our house had not burned. And truly, wondrously, our little old house had been saved from the tongues of flame.

In 1916, during another retreat, the Russians carried all of the older males of the city away with them. A short time after the entry of the Austrians (or Germans,) our family went to Mern.

There, I worked for a rich farmer in the village of Dembuzce, though I was all of eleven years old. Among other things, I would feed and provide water for eight cows, clean the barn, and work in the field. There is one incident that burrowed into my mind and remains etched there to this day. Once, I traveled with the master in a wagon full of manure, I serving as the driver. All of a sudden, the reins “became confused” and the cattle (that were used to plow in Mern) veered from the road into the field we were passing. The master, his eyes full of rage, shouted at me: “Jew!”

After our return to Rohatyn, the turbulence of two new wars descended upon us: the war between the Poles and Ukrainians, and the war between Poland and the Soviet Union. And, of course, Jews were persecuted on all sides. The poles and Ukrainians would shave the beards of the pious Jews, beat them, and brutalize them. A Polish officer accused my brother of treachery, because he had fastened a telephone apparatus to his rooftop, through which he had established contact with the Bolsheviks. This meant certain death, but, miraculously, my brother was saved.

At the end of 1918, I was studying in the local Polish gymnasium. Once, my Russian language teacher heard me chatting with my friends in Yiddish. The next day, this teacher mocked me and beat me for nearly an entire hour, in order to expose me to scorn and ridicule for having “stammered in the tongue of my people”—in Yiddish.

During my years in middle school I gave private lessons for a fee, in order to support my parents and lighten the load they carried in providing for the household. In 1925, after passing the matriculation exam, I began studying at the university in Lvov, in a humanities program. Due to the anti-Semitic riots of the students, I was more than once afraid to walk between the walls of the university, because of the beatings they gave us.

After completing my degree, I received a teaching position at the city gymnasium in Kalosh. Among the faculty, twelve in number, there were only three Jews. We were hired according to a yearly contract. Each year we worried afresh over whether or not these would be renewed by the authorities, and over which Jewish teacher would lose his job.

After the outbreak of World War Two, I continued working in the education administration in Kalosh, though now under the authority of the Soviets. In 1940, I was in Rohatyn for the last time. My mother was already sick and bedridden. My father clung to her with devotion and warm-heartedness. Poverty and destitution ruled the house. Their only consolation was the marriage of my sister Clara to a respectable man in Stanislovov.

In the same period of time, I saw my immediate family and relations for the last time: my brother Shmuel, a lawyer in Rohatyn, who for years has sat at the head of the local Zionist organization; his wife Plitsiah and their lovely and intelligent two year old daughter; my uncle, Rabbi Avrum-Dovid Spiegel, a man distinguished for his kindness, righteousness and wisdom, and also his family; my uncle Pinchas Spiegel, who devoted all the days of his life to the Zionist ideal, and his family; my aunt Golda, beloved of all, and her family (her son Chaim now lives with his family on Kibbutz HaMapil.)

With the outbreak of World War Two, I fled with a friend to Russia. On my way to Russia, I stopped in Stanislovov, to say goodbye to my sister Clara. She and her husband did not want to leave our elderly parents, who were not strong enough to withstand the hardships of wandering from place to place, behind. Soon after, all of my family went to their graves, along with the rest of Polish Jewry, killed by the murderous Nazis.

In 1944, I sent a letter from Russia the town of Rohatyn, inquiring after the fate of my family. I received a letter on the 16th of December 1944, with the following response: “The city council of the Labor Ministry in the city of Rohatyn informs you in response to your inquiry that of the family of Dr. Spiegel, Shmuel, not one remains alive. The Germans murdered all on 20 March 1942. Signed: Vice-Chairman of the City Council Stulartsuk.”

In 1946, we returned, my friend and I, to Poland, and from there we immigrated to Israel in 1957. Here, we awoke to a new life, and I believe with a full faith that sooner or later the verse will be fulfilled: “They will return from the land of the enemy…the children will return to dwell within their borders.”

[Page 124]

A City of Torah

by Leybush Zukerkandl, New York

Translated by Binyamin Weiner

We were three brothers: Itsik, who was the eldest, myself, and my younger brother Aaron. Our father, a learned Jew, was also knowledgeable in worldly matters. He was an expert in the Polish language and had wonderful handwriting. He used these skills in the service of anyone who sought his help, writing petitions to Polish institutions and attending to matters affecting the Jews. He was always immersed in communal business. Even in his later years, when he moved to Lemberg, his tobacco and newspaper shop served as an inn for traders from Rohatyn, who would heed his words of advice and maintain their connection with this dear friend.

|

|

| Moshe Zukercandl and his wife Blumah, with their children: Yitschak, Leybush (in America), Batiah (in Israel), and Aaron |

Our strict Jewish education, which every Jewish parent of the time expected of his child, began with Moshe-Gershon the melamed, and continued with Urtsi Menahel, the Gemara melamed. When we grew older, we were delivered into the faithful hands of the “young Dayan,” Rabbi Spiegel, a dear friend from then on. We were among the chosen few who merited learning from him, and it must be emphasized that the Rabbi taught us without the expectation of reward. His students included the distinguished Eliyahu Mesing (the son of Avraham Mesing,) my brother Yitschak, may he rest in peace, and myself, the present writer.

I will never forget my period of study with Rabbi Spiegel: his patriarchal demeanor, his gentle and majestic face, his appearance on state birthdays, and the way he would interrupt his lessons in order to address some question that had arisen, regarding a matter of meat and milk. Nor will I forget his clear and lucid explanation of the laws concerning kosher and treif.

In the winter we arose at four in the morning, and walked with a lantern in our hands (not every boy was lucky enough to have his own lantern,) to study at the beis-midrash. There it was a special privilege to receive a candle from the gabbai, to serve as light for three or four boys.

But all of this, these memories that still bring a smile to the lips, now belongs, much to our sorrow, to the past. To those of us, however, who were fortunate enough to see how this city stood out and to know how it serves as an inspiration—to us Rohatyn still remains a city of enlightened men and the study of Torah.

But “the Glory of Israel will not fail.” We were worthy enough to see with our own eyes the founding of the state of Israel, and we will hope that, despite all of our enemies, Israel will yet flower and flourish, and that there the mourners of Zion will be comforted for their terrible shoah. Amen. May it be so.

[Pages 125-127]

The City and its Images

by Uri Mishor

Translated by Binyamin Weiner

I myself am not a son of Rohatyn, but of one born in Rohatyn. This was my father and teacher Reb Avraham, son of Reb Uri Todfeler, may the Lord avenge his blood, whose family came from Rohatyn and flourished there.

I often recall my visits to the city, from year to year during my youth, when I was on vacation from my studies. I would stay as a guest with my uncle and aunt, and their family. These were: Kubler, Beigel and Averbuch.

I arrived in the city on the train that crossed the bridge over the river Gnila Lipa. The Jews lived in the center of town, and in the very center of the center itself there was an aqueduct, with the river water still flowing through it. I have known many cities and towns in Poland, but in none of them have I seen water supplied to the inhabitants after the manner of Rohatyn.

I too came to Rohatyn to draw its water, that is to say its Torah, for there is no water but Torah, from the wells of Torah and hasidut that were our great Rebbe and teacher Rabbi Shlomeleh, of blessed memory, and his son Yehudeh Tsvi, of blessed memory. The later taught us chapters of Gemara. How great was his passion during lessons in the Eclectics of the Ba'al Tanya (Rabbi Shneour Zalman of Ladi,) on the divine substance: “Oy, oy, the wicked men, the heretics ask, 'Where is God?' Oy gevalt, how shall we answer them? 'There is no place where He is not!' All the wicked men, all the heretics ask, “What is God?” How shall we answer them? 'There is no thought can imprison Him!'”

|

|

| The bridge on the river Gnila Lipa |

I also studied with my uncle, Reb Moshe-Leyb Kubler, may the Lord avenge his blood. He was always festive, never complaining the lack of anything, and he received both good and bad fortune with love. Indeed, during the time I spent with him his material conditions were truly good. He paid little attention to business matters and much to the study of Torah. He always prayed in the shul of our grand Rebbe and teacher Rabbi Eliezerel, of blessed memory, where he was also the regular Torah reader. Every day, after finishing the morning prayer, he came home to eat breakfast and then returned immediately to the “shtibel,” to study his regular lesson of Torah: the weekly portion along with the interpretation of Ibn-Ezra, whom my uncle considered superior to all of the other commentators.

On Fridays, he released me from my studies, because, as the reader, it was his responsibility to prepare the Torah chanting. He was strict about every single note, not lengthening when he should shorten, and not shortening when he should lengthen.

|

|

|

| Chaim Kubler as an Austrian soldier, Binyamin his son,) Malkah (his wife,) and Henni (his daughter) |

Sabbath all of peace

These were Jews who lived by Torah and service, “service” meaning the service of the heart. And what is the service of the heart? It is prayer.

And these were Jewish merchants, immersed in business day and night, who still fulfilled their Jewish obligations at all times, through acts of loving-kindness and charity, even when involved in business matters and even through leniency to Gentile customers.

My cousin, Reb Chaim Kubler, may the Lord avenge his blood, was one of them. He was ever immersed in business matters, but was nonetheless devoted to the charitable relief of poor wayfarers, who would wander from village to village and city to city, gathering alms. In Rohatyn, they did not have to pass from doorway to doorway, but instead received a special, bi-weekly or monthly stipend, financed by my cousin. Every poor wayfarer received a stipend according to his turn, as recorded in a register. My cousin undertook this project out of goodness, and not in expectation of reward. He kept his door always open, to provide relief for those in need, never fixing only certain hours for receiving the poor.

These people, and many like them, devoted their entire being and existence to the performance of good deeds, and fulfilled their obligations in simplicity and sincerity. Woe onto us that they were killed before their time. May the Lord avenge their blood.

|

|

They were four friends

Standing from right: Yosef Bir, Chamba Mandel, Yitzchak Krieg (living in Netanya), Yechezkel Atner (seated). It is said of the latter that he arose against the enemies in our town and shot at them. |

[Page 128]

Community Life in Rohatyn

by Natan Melzer

Translated by Binyamin Weiner

Rohatyn is preserved in my memory as a town rich in communal life, centered on the “Bnei Zion” association, which met in the house of Mendel Bernstein. There I learned to play chess, found newspapers to read, and debated both the Zionist matters on the agenda and matters regarding the Jewish world in general.

Herzl died during that time, and we all carried the weight of this tremendous loss. I still remember how the newspaper “Di Velt” brought out a special edition, set against a black background, and the letter from Herzl's widow Julia that was published within. We were like orphans without a father, and for months the burden of this loss lay upon us, without respite.

The Jewish community of Rohatyn, led by Alter Weidman, was among the first in Galicia to establish a modern Hebrew school, inviting the esteemed pedagogue Rafael Soferman, may his memory be a blessing, to serve as its principal.

In addition to Zionist activity, there was also a great deal of activity surrounding elections for the Austrian parliament. There were three candidates for the Rohatyn-Bzezany district: Dr. Shmuel Rappaport, of the Jewish nationalist party, Dr. Nebokovsky, of the Ukrainian party, and Vladislav Dulmbeh, of the “Voice of Poland” party. None of the candidates received a sufficient margin of votes in the first round of the elections, and in the second round Dr. Rappaport was still struggling against the Polish candidate, though his chances seemed slim.

Among the Jewish merchants of the community, Sender Margalit, Jacob Fish, Shalom Melzer, and Alter Weidman (the aforementioned chairman of the community) should be recalled. The Jewish representatives of the town participated in a body with the Ukrainian representatives, in addressing all local problems.

My father, may his memory be a blessing, Shalom Melzer (the son of David Melzer the Kohen, who immigrated to Israel and settled in Safed,) was one of the founding members of the Zionist association “Bnei Zion.” He was elected to the communal board and the city council and served as a liaison with the Zionist center in Lvov, led by Dr. Adolf Shtand. He was also a business representative for the “Carmel” company.

|

|

Shalom Melzer,

may his memory be a blessing |

[Page 129]

In Memory of Moshe Lewenter,

of blessed Memory

by Joseph Green, Tel Aviv

Translated by Rabbi Mordechai Goldzweig

We had been friends from childhood, tied together body and soul. We went to

grammar school and gymnasium together. Our studies were interrupted by the

Russians, who rounded up all the Jewish males during World War I as they left

our town, and still we were not separated. We were together in Ponza until we

received permission to return to our homes. On the way back we were forced to

remain for two years in Tarnopol until it was conquered by the Austrians. In

Tarnopol we studied in the Polish gymnasium (under the supervision of the

Russians) until we were liberated by the Austrian Army when they conquered the

city. Two months later we were drafted into the army in Lwów. This time we were

separated – Lewenter was sent to Przemysl and I was sent to Bielice. This

separation was difficult for both of us. We felt that this would be the end to

our friendship. Shortly afterward I was informed that my friend, a most

wonderful person, had become ill in Przemysl and died of pneumonia. His memory

will never leave my heart.

Fragments

In 1918 Pinchas Spiegel, Chana Wachman, of blessed memory, and I, the writer of

these lines, founded a hospital in Rohatyn to save the lives of Jewish soldiers

who were returning from the war and had contracted the plague. Thanks to this

place we succeeded in saving many of them.

After World War I, aided by the late Dr. Goldschlag, we formed the Histadrut

Poalei Zion (Zionist Labor Organization) in Rohatyn. We acted as counselors to

the youth who engaged in lively and energetic activities. We founded a football

club as well as a wonderful theatrical group, a picture of which I have

included. This drama club enriched the cultural life of the town.

|

|

| A play,

The Jewish Refugee, directed by Joseph Green |

[Page 130]

Cherished Images

by Leah Zuch, Tel Aviv

Translated by Rabbi Mordechai Goldzweig

Rohatyn, together with its dear Jews, was destroyed during World War II, but

the beloved images of our holy martyrs still appear before our eyes, and it is

hard to forget them.

Yes, this is the town, covered with greenery where our ancestors had lived for

generations. I can still picture my grandmother, Dvorele Moshele's (Wagschal),

lovely and gentle, returning from the synagogue in her scarf and fine silk

clothes. How proud I was of her!

I remember the Purim “Seudah” [festive meal] in my parents' home. That evening

many children of the town would come to our house in their costumes. Especially

noticeable were the groups of students who portrayed historical figures,

including those of the Megilla. Others came from Zionist youth groups, wearing

blue and white sashes emblazoned with the Star of David. These were joined by

four klezmerim (musicians) from the Faust family who played typical Jewish

melodies and ended their musical performance with “Hatikvah.” The faces of my

father, Akiva Wagschal, and my mother, Cyril, would shine with joy upon every

display of Zionism in the town. My father, who was a Zionist, heart and soul,

was one of the founders of the Hebrew School of Rohatyn and had also been

privileged to visit Israel.

After World War I we were among the approximately thirty university students

considered to be the “Golden Youth” of Rohatyn. However, none of our knowledge

or personal qualities helped us to obtain a teaching position in the local

gymnasium - only because we were Jewish. Those were the days of the infamous

quota system.

I still remember the libel case staged against Steiger who was falsely accused

of attempting to assassinate the president of the state.[Ed1]

We of Rohatyn were particularly interested in this trial, since Steiger was

the son-in-law of a Rohatyn townsman, the husband of Józka Mark. If we had only

been wise enough to pay attention to the warning signals of those days…

Nonetheless, on the “Third of May,” the national holiday of Poland, we Jews

would watch the celebrating throng of “Sokolim,” i.e. cadets, march and sing,

"Poland Has Not Yet Perished” [Polish national anthem]. They were joined by

school children who marched with them in the parade. At that point attorney Dr.

Alter would call out, “Next year in Jerusalem!” How unfortunate it was that he,

as well as thousands of other Jews of Rohatyn, were not privileged to reach

this goal.

And so it is that our souls mourn…

|

|

|

Two student groups in Rohatyn:

To the right: Ludwik Katz, Salka Zuch, Ze'ev

Halpern, Unknown, Izzie Scharer, Shaiku Panzer

To the left: Unknown, Dr. Avraham Sterzer, Salka Zuch, Unknown, Julek Szkolnik, Busko Scharer, Manka

Feld, Grina Faust, and Ludwik Mondschein |

[Page 131]

My Home That Is No More…

by Chaya Weisberg (Weinreich)

Translated by Rabbi Mordecai Goldzweig

|

|

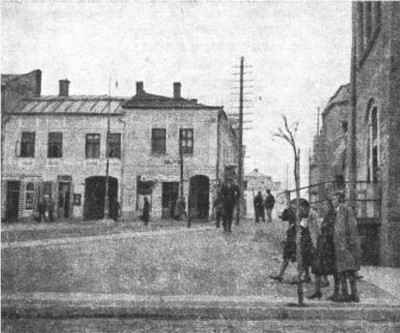

To the right:

The Ukrainian house, the house of A. Kartin; Opposite: The house

of Noach Becker;

To the left:

The house of Moshe Preiss, which is attached to

the house of Yisrael Zilber with a passage between them. At the far edge of Max

Zilber's store, you can see the open area of the market square [Rynek].

Photo from 1932 |

It is generally on days of rest that I think about the town of Rohatyn that was

destroyed and is now totally gone.

Our little house faced Cerkiewna Street. This street led from the market square

to the bath house near the Gnila Lipa River. This was the only place where we

could enjoy ourselves during the summer, tanning in the sun and swimming in its

cold waters to our delight. The treetops of the forests appeared across the

river, and in the months of January and February, they were covered in white,

attracting both young and old.

We had many neighbors near our house. Even now I remember the Gottstein family,

the Winter family, Gitel Weiner and her two daughters, Sheva and Roiza, the

Fried family (mother and son), and Yisrael-Leib Gottlieb (the grocery man) and

his family. They lived peacefully, undisturbed by the noise on the street

emanating from the workshops and lumber yards of Alter Faust, Allerhand, or

Liebling.

The town could easily be identified as Jewish by the many beards and curly

payot [side-locks] that were to be seen there. Moreover, there were also many

expressions of vibrant nationalism to be found within the Jewish community.

Hundreds of young people were members of youth groups such as Hashomer Hatzair,

Hanoar Hatzioni, Gordonia, Hitachdut, Betar, and Halutz, to which I belonged.

The war of annihilation by the German murderers came and put an end to all the

future prospects of Jewish existence. And my heart aches within me…

Footnote

| Ed1 |

|

[In Lwow, in 1924, a bomb was thrown at a carriage carrying the President of

Poland, Stanislaw Wojciechowski. A Jewish university student, Stanislaw

Steiger, was accused of attempting to assassinate him.] Return |

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Rogatin (Rohatyn), Ukraine

Rogatin (Rohatyn), Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Feb 2025 by LA