|

|

|

|

|

[Pages 10-67]

History of the Jews of Rohatyn

by Dr. N. M. Gelber

Translated by Rabbi M. Goldzweig, edited by Fay and Julian Bussgang

The Polish and German footnotes and the exhibits in the German language

were translated by Donia Gold Shwarzstein

A. Historical Background

The town of Rohatyn is situated in Galicia on the shores of the Gnila Lipa River. Its recorded history began as early as the 12th century, and the events therein left their stamp for future generations. There are not many documents available from the earliest periods of its history, but from what there are, the following picture appears. Rohatyn first began as a small village that slowly grew, deriving a good amount of its income from marketing fairs. It does not seem to have constituted a special political entity of its own, in the beginning, but was attached to other areas and was politically affected by what happened in the surrounding areas. It began as a village, and it became a town in the 13th century. From one document we learn that in 1375 King Wladyslaw gave the town of Rohatyn to the Cardinal of Wlodislaw.[1] [Ed1]From this period until about the middle of the 15th century, we do not have any information. Around 1444 the starosta (district administrator) of Rohatyn was Wolsko, who was followed by Mikolaj Paraba of Lubin in 1444.[2] In the year 1460 the town and its surrounding areas were transferred to the ownership of the Parait family from Chodecz as a pledge for a loan made to King Casimir Jagiellonczyk (Kazimierz IV, 1447–92). During this period, as we learn from various documents, Rohatyn was doing business with Zydaczow.[2a]The yearly town market fairs became so successful that they interfered with the trade of the city of Lwow and caused it a serious loss of income. Whereupon the voivode (provincial administrator), Andrzej Odrowaz, petitioned the king to abolish the yearly trade fairs in Rohatyn, which were so damaging to the city of Lwow. On 23 June 1461, King Casimir Jagiellonczyk responded by abolishing not only the Rohatyn fairs but also those of Tysmienica, Trembowla, Gologory and Jazlowice, which apparently had also contributed to the loss of income to the city of Lwow.[3] These restrictions applied only to the regional fairs. The local market days were permitted to continue, and by the 16th century they grew beyond the scope of a local fair.[4]In the 15th century we learn that Rohatyn received a singular honor when the Halicz district parliament (sejmik halicki) met there.[Ed2] Until then it had been meeting in Sadowa Wisznia.[5] Living among the Slavic inhabitants of the town were also people of German descent. Included among them were Johannes, “the famous citizen” of Rohatyn, procreator of Petrusi, Raphal, and Otto, German brothers[Ed3] who did business with the nobility.[6]In 1482 a suburb was added on the other side of the entrance to the town near the gate that was termed “Suburbium Rohatinense,”[7] a place that would be associated with the history of the Jews for hundreds of years thereafter. At that time, legal matters were still carried out for the town in the courts of Halicz.[8] In 1523 Otto of Chodecz, voivode of the province of Sandomierz and a starosta in Red Ruthenia,[Ed4] tried to improve the position of the town by granting it a special permit to carry out special fairs known as sochaczki[9] every Saturday during the period between Wielkanoc (Easter) and John the Baptist Day (June 24). This permit applied only to the butchers of Rohatyn and only during the three months before the Holiday of the Three Kings. However, after the fairs, cattle belonging to the inhabitants of the area could be brought to Rohatyn to be slaughtered and sold upon payment of a fee to the national treasury of a groschen for each ox or cow and six denars for each sheep or goat. During that year, a bridge was erected and paved, the use of which required, by order of the voivode of Red Ruthenia, the payment of a toll of two denars for each wagon and one denar for each horse.[10] In 1533 the government transferred the proceeds of this fee to the town.[11] After the death of Otto of Chodecz, the town again became the official property of the king,[12] and the first starosta was Johann Boratynski.[13] In the year 1535 King Sigismund I applied the Magdeburg law to Rohatyn and thus exempted the town from the payment of a number of taxes (on such items as eggs, cheese, spayed chickens, and oats) and permitted the hewing of wood in the forests. Because of incursions into the town by surrounding enemies that caused great damage, the king granted Rohatyn a special “privilege” in 1539 that permitted it to erect fortifications and a protective wall, the expenditures of which the king subsidized from taxes on liquor and szos (paved roadways). He wrote in the privilege, “Desiring that the town grow and develop, it shall be surrounded by walls, and we permit the erection of a citadel in the center of town, including a town hall with a tower.” The expenses for the maintenance of this citadel were to be derived from taxes on the sale of textile remnants (postrzygalnia) and liquor. According to a survey in 1572, the town had a population of 115 homeowners, 18 tenants, and 36 citizens who lived on the outskirts, while the new town held 100 homeowners and 11 tenants. In 1578 Rohatyn paid seven hundred gulden in taxes on liquor.[14] The condition of the inhabitants at this time had deteriorated so much that apparently King Stefan Batory issued an order on 12 December 1576 exempting the town from payment of levies and taxes except for customs at the borders. This directive was sent to all of the customs offices and tax collectors.[15] In reaction to this directive, a quarrel broke out between the customs inspectors of Red Ruthenia and those of the village of Rohatyn, because the people of Red Ruthenia did not wish to recognize the decree of the king and demanded the payment of duties. The issue came before King Stefan Batory on 4 August 1578 in Lwow, and he confirmed that the inhabitants of Rohatyn were required to pay only customs at the border.[16] During these years, there existed a variety of guilds. Of note are the goldsmiths who received a special charter from King Stefan Batory on 15 June 1575. Among the best known of their works were those created by Bartolomy.[17] Another attempt by the king to improve conditions in the town was a call by His Majesty to all merchants and travelers not to encroach on the town of Rohatyn. In the 16th century the town was attacked by the Tatars. In one of their incursions, they kidnapped Anastasia, the daughter of the local Ruthenian priest Lisowski, who was sold into the harem of Suleiman I. She found favor with him to the point where she became his first wife, taking the name of Roxolana. For a time, she even directed the official policies of Turkey.[18] In the 17th century the Cossack bands began their attacks on Poland. In 1615 an intensive battle was waged against them near Rohatyn, and the Hetman (Commander) Zolokowski succeeded in destroying them as well as capturing their leaders and executing them. In 1616 King Sigismund III permitted the erection of a public bathhouse known as the Babinski Patopek on the Babianka River, and the income from it was transferred to the town for its expenditures.[19] The Chmielniszczyzna (followers of Chmielnicki), a Ukrainian anti-Polish movement, expanded into the Rohatyn area. Ruthenians from there joined them in their military preparations and maneuvers. Together with other Ruthenians from surrounding towns, they took part in military attacks on the manors of the nearby Polish nobility, threatening not to leave one “Polak” alive. The Ruthenians of Rohatyn were filled with a burning hatred toward the Catholic religion, monasteries, and churches.[20] According to a survey dated 1663, the town had two hundred houses in the old town and thirty-one in the new suburb. The residents complained that the podwodne [20a] they were forced to pay was unfair.Despite its relatively small size, the town had a wide variety of guilds – tailors, weavers, cobblers, butchers, bakers, furriers, belt makers, musicians, blacksmiths, iron mongers, harness makers, and armorers. Tinsmiths, saddle makers, and carriage makers were united into one guild. In the 1670s the starosta was Sigmund Karol Pszaromski, followed by the nobleman Adam Mikolaj Sieniawski, who carried out many important duties in the community. For a number of years he was the president (marszalek) at sessions of the district parliament (sejmik) at Sadowa Wisznia. [21] In the 17th and 18th centuries the town became known as a center for the sale of cattle, horses, and agricultural products. To the town were attached the villages of Perenowka, Firlejow, Podgrodzie, Zalipia, and Zawadowka. In the census of the year 1765 the population of the town numbered 539. The starosta was Franciszek Bialinski, and the net income for the district rose to 37,560 gulden per year. At that time, the town belonged to Jozef Bielski.After the conquest of Galicia by Austria, Rohatyn was transferred to the noblewoman Zofia Lubomirska as partial compensation for her Dobromil manor, which was taken by the Austrian government. [22]Under the Austrians, the town grew. In 1857 Rohatyn had 5,101 inhabitants. In 1870, 4,510; in 1880, again 5,101; in 1887, 6,548; in 1890, 7,188 and 914 houses; in 1900, 931 houses and 7,201 inhabitants; and in 1910, 7,664 inhabitants. In 1921 the population was reduced to 5,736 because of World War I. In 1885 occupations in the town of Rohatyn included:

Merchants, 51: textiles, 3; shoes, 11; iron, 2; eggs, 1; grain, 13; glass, 1; flour, 12;

agricultural products, 4; and wagon grease, 4;

Crafts: furriers, 2; tailors, 1;

Leaseholders: millers, 1; bartenders, 1.In the general area of Rohatyn, there were 1,290

people in different occupations. They included as follows:

Trades, 393 merchants: wine, 11; textiles, 35; spices, 16; wagon grease, 7; salt, 12; handicrafts,

6; flour and cereals, 14; hides, 19; cattle, 8; horses, 5; petroleum, 5;

lumber, 8; whiskey, 4; flooring, 1; eggs, 5; iron, 12; fish, 4; grain, 43;

fruit, 5; haberdashery, 53; peddlers, 5; moneychangers, 5; middlemen, 3-4;

brokers, 3; retailers, 95.

Craftsmen, 520 workers that included: tailors, 55; furriers, 21; hosiers, 4; weavers, 18; cotton wool

makers, 2; rope weaver, 1; soap makers, 7; shoemakers, 58; chimney sweeps, 2;

comb makers, 3; charcoal makers, 2; metal forger, 1; stonecutters, 2;

carpenters, 26; potters, 21; precious metal smiths, 2; watchmakers, 5;

glaziers, 7; tanners, 4; bronze coaters, 1; coachmen, 12; belt makers, 4;

woodcarvers, 3; bookbinders, 4; butchers, 44; wooden house builders, 25;

blacksmiths, 20; ironmongers, 4; insulation, 4; gardeners, 2; millers, 58;

mechanics, 2; fence-makers, 19; harness makers, 4; wood cutters, 3; musicians,

4; barber-surgeons, 17; builders, 3; painters, 2; bakers, 16.

Leaseholders, Bartenders, Suppliers, Druggists, Factory Owners, 337, including:

Leaseholders of mills, 49; owners of mills, 40; tavern keepers, 96; leaseholders of inns, 7; owners of blacksmith shops, 2; distillery owners, 13; bartenders, 152; distillers, 2; meat suppliers, 2; partition suppliers, 3; fodder suppliers, 4; milkmen, 4; soda water suppliers, 2; druggists, 4. In the year 1889 the town of Rohatyn transferred its records to the state archives in Lwow, among them a large number of documents, such as thirteen permits and charters from the years 1438, 1525, 1535, 1539, 1567, 1581, 1603, 1663, 1669, 1676, 1729, 1738, 1796.[23] After World War II this important historical treasure remained in the hands of the Soviet Union.

B. The Beginning of the Jewish Community

There is no way of knowing when the Jewish community of Rohatyn began, since we

do not have any documents attesting to its beginning. We only know that by the

end of the 15th century, Jews of Red Ruthenia and other parts of Poland were

coming to the market fairs to buy cattle that were, in turn, sold in Silesia

and Western Poland. They also bought horses that were brought there from

Hungary.[24] We learn from one document, dated 1463, that one of the cattle

wholesalers was a Jew by the name of Shimshon from Zydaczow. He bought cattle,

oxen, and horses from the landowners of the areas around Rohatyn. In 1463 an

agreement was reached between the Polish nobleman, Johann Skarbok, and the

Jewish wholesaler, Shimshon, from Zydaczow. According to this agreement,

Skarbok would provide Shimshon with the use of his town, Olchowiec, in the

district of Halicz, for the rental fee of forty marks, and Shimshon would agree

to accept five hundred head of cattle (peccora quinta) from him to be sold at the next fair in Rohatyn. In the event that the fair

did not take place in Rohatyn, Skarbok was to deliver them in Olchowiec.[25]

Shimshon also did business on a large scale with other nobility in the Rohatyn

area, where he was the major buyer at the Rohatyn fairs in the years

1447–64. As a result of this, Jews began to settle in Rohatyn. Jews are

first mentioned in legal documents of Rohatyn dated in the year

1531.[25a]During the 15th and 16th centuries their numbers were still quite small, and

they did not as yet have an organized community. They were subject to the

jurisdiction of the Jewish community of Lwow. The residents of the area were

directly tied to the kahal

(Jewish community council) of Lwow, or through one of its branches in the

district of Halicz. As the town expanded and became a larger marketing center,

more Jews were attracted to settle there, since the town needed skilled

workers, retailers, and peddlers. In the year 1582 the collection of taxes on

liquor in Rohatyn was leased to Mendel Izakowicz for an unknown number of years.[26]On the other hand, Rohatyn, a crown property, did not grant the right of

citizenship to Jews or anyone else who was not a Catholic, in contrast to

“free” towns, not officially under royal jurisdiction, whose economic

interests led them to grant Jews rights equal to their other inhabitants. They

even gave Jews the right to vote for members of the town council, as

exemplified by Brody, Dukla, Zmigrod, etc.As a result, Jewish inhabitants in

areas like Rohatyn, who were not under the jurisdiction of such towns, did not

benefit from the provisions of the Magdeburg law, which provided for the

administrative and judicial independence of municipalities. They were deprived

of the possibilities of taking part in some of the economic endeavors

available, such as the distilling and sale of hard liquor. Since the Jews of

Rohatyn lacked a charter, the economic rules that applied to them were

different from the rest of the community, with the exception of sales connected

with the yearly fairs. Thus, during this period, the number of Jews in the

community did not increase in proportion to those living in “free”

towns.Changes in the development of the Jewish community of Rohatyn did not

really gain momentum until the year 1633 when King Wladyslaw IV granted them a

charter that was continued by King John Casimir (Jan Kazimierz) and restated

again by King Michael (Michal) in 1669. This charter laid the foundation for

the legal establishment and organization of a Jewish community. In it he states

that he, King Michael, reaffirms and validates the charters of earlier origin

granted to the Jews by his predecessor, Wladyslaw IV, on 27 March 1633, and

continued by John Casimir on 21 May 1663, and on this, the day of his

coronation, the 22 November 1669, (he reaffirms) the plan and contents of the

privileges previously presented in their magnanimity by his predecessors.[27]

The text states in part, after a prologue written in Latin, that “on the

fifth day after the religious holiday Purificationis Beatissimae Virginis Mariae,[27a] there appeared by himself, in the town of Lwow, the Jewish intermediary

(Jacob)

Selig[28], who presented the signed charter by His Majesty for registration

in the archives of Lwow and addressed in His magnanimity the Jews of Rohatyn,

the text of which states as follows:

“Polish king Wladyslaw IV (followed by all of his titles) publicly declares that whereas We have accepted in this, the coronation session of the Sejm, all of the laws of our kingdom and of those of the cities, do We, in keeping with the petition of the Jews in Our town of Rohatyn, reinstate and recognize all of the privileges, decrees relating to surveys of the houses and lots where they live, the synagogue, the cemetery, all trades, and businesses without distinction as to buying and selling, and the buying and selling of lead and other goods; they are permitted to keep taverns and the varieties of liquor in them, to brew beer and mead, to distill whiskey; they further have the right to sell and buy cattle, meat, whole or in parts, in the town square (rynek), in keeping with their past marketing customs, being equal with the townspeople according to privileges, and without prejudice, as practiced in the town.

“As to the taxes on the Jews, they are to pay city taxes similar to those paid by the townspeople but are not required to pay 'private taxes.' On the other hand, taxes that they have been paying, according to law and earlier customs, are to be maintained.

“His Majesty authorizes all customs and laws that were enjoyed previously to the extent that they are still in use and do not violate the body of the laws as a whole. In addition to this present authorization, we do give our promise that they will continue to remain in effect.”

It is stressed in the charter that the Jews of Rohatyn had presented a petition in writing asking that the third day of the week, their traditional market day, be continued and recognized as found in previous documents. The king granted their petition, taking into consideration their right to recuperate from the ravages of enemy incursions and to operate their business affairs to their best advantage.

The charter instituted rules for the legal maintenance of the Jewish economy and insured their rights, permitting them to conduct their business legally. The salient passage here is “rowno z mieszczanami tamecznymi wedlug przywileju i starodawnego zwyczaju” (on a par with the local citizens according to the privilege and longstanding customs). We see that equal rights were ensured to all residents of the town. In contrast to Jews in a number of other towns in Red Ruthenia, they were free of various levies such as the supply of tools; participating in the construction and repair of roads, repair of bridges and town walls; tributes to officials, the church, and the priests, etc. These special rights derived from the permission given to the Jews to maintain their stores in the center of town and their freedom of trade. These rulings did not cover the socio-legal organization of the Jewish community, since the community of Rohatyn developed in the same fashion as other Jewish communities in Poland. It is quite possible that by the 17th century, the Jews of Rohatyn had received a charter in this area as well, but there are no definite documents to validate this assumption with certainty.

In practice, the Jewish community of Rohatyn was one of nine communities that

were included in the general Jewish community of Lwow prior to the attacks of

Chmielnicki. These communities included Bohorodczany, Buczacz, Brody, Zolkiew,

Tysmienica, Lesko, Zloczow, and Rohatyn. The officials under the jurisdiction

of Lwow included the chief rabbi. As in all other Polish communities there was

a Va'ad

(governing council) consisting of:

The officials of the community were the rabbi (rav), judges (dayanim), the preacher (darshan), the scribe (sofer), and the beadle (shamas). An intercessor (shtadlan) represented the Jewish community before the government when the need arose. Thus we find Selig, the Lwow shtadlan, presenting the charter granted by the king of Poland for entry into the official books of Lwow. Rohatyn, a small town, was unable to maintain its own shtadlan and thus employed the services of Selig from Lwow. Many heavily populated communities kept a doctor, a druggist, a nurse, a midwife, guards, collectors, and messengers in addition to the above. To what extent this existed in Rohatyn, we do not know. Even in Rohatyn, there existed organizations for burial, etc.

Since Rohatyn in the 17th century had within it a large number of craftsmen in various categories, it also had many trade unions that stood guard to protect their interests within the Christian guilds, the municipality, and within the governing committee of the Jewish community as well.

In 1658 at the request of the Red Ruthenian nobility at the sejmik in Sadowa Wisznia, there were established Va'adei Gelilot (Jewish district councils) which in the end resulted in the creation of a council for towns surrounding Lwow and eight additional Jewish communities.

In practice, it was the kahal (Jewish council) of the city of Lwow alone that directed all the activities of the regional council, to the point where the parnassim of Lwow had concentrated under their control the enactment of all the activities of the kehilah (Jewish community). They stood guard to protect this hegemony from falling out of their hands and thus excluded the kehilot (Jewish communities) within the eight provincial towns. After the wars during the 17th century and the revolt of Chmielnicki, the kehilah of Lwow sharply decreased in size. In its place, politically, there emerged the provincial towns, which effectively took the leadership away from the parnassim of Lwow in the national Jewish council. The kehilah of Zolkiew, which hitherto had been considered a branch (przykahalek) of the Lwow Jewish community, succeeded, with the aid and support of King Jan Sobieski, the owner of this royal town, to free itself completely from the domination of the Lwow kehilah. It also went on to take control of the regional council, together with the kehilot of Brody, Tarnopol, and Buczacz. This enabled the rabbi of Buczacz to be elected chief rabbi of the whole region. Among the other kehilot that joined it were Rohatyn, Lesko, and Zloczow, whose representatives were included among the heads of the new executive council of the area.

The declining economic conditions of Lwow forced many Jews there to leave the city and settle in the eastern towns of Red Ruthenia. To what extent this affected their coming to Rohatyn is hard to tell. One thing is certain, that due to the continued wholesale exodus of the Jews from Lwow eastward, the city was so weakened that they were unable to fulfill payment of their required head tax that was placed on the small number of Jews remaining there. This fact was brought to the attention of the sejmik of Wisznia on 18 April 1701.[29]

The members of the nobility complained that they were not obtaining their tax money because large numbers of Jews were leaving for Podolia, then under the Turks, where there was no head tax. They therefore asked that the taxes be reapportioned for the existing number of inhabitants. The sejmik approved the request but did not put it into effect until fifteen years later in 1716. Eventually, Red Ruthenia and Podolia were given different tax schedules from then on.

In 1664 the kahal members from the nearby towns of Buczacz, Zolkiew, Jaworow, Kolomyja, and Brody attacked the Lwow contingent at the Va'ad Hagalil (district council) meeting in Âwierz and forced them to revise their monopoly to include the views of their neighbors that had heretofore been ignored. This brought about the addition to the council of seven more members from the nearby towns. The council, which met in Kulikow in 1720, had fourteen members – five members from Zolkiew, three from Brody, one from Bohorodczany, one from Stryj, one from Rohatyn, one from Zloczow, and one from Buczacz.[30] Among the issues that this session dealt with, on 11 Tamuz 5480 (17 July 1720), was the (previous) unseating of the Gaon Rabbi Yehoshua Falk, author of Pnei Yehoshua, from his office as rabbi in Lwow.[31] This council, which included Rohatyn, unanimously voted to return the Gaon to his office, which had been taken from him and given to Rabbi Chaim ben Leizerel, Rabbi ben Leizerel having been elected through the intercession of his father-in-law, the purchasing agent for the voivode Jablonowski.[32] The representative from Rohatyn, Zvi Hirsh, took part in this.

C. Economic Conditions

During the 17th century, the area of Halicz and its surrounding towns were prey to violent attacks and invasions by Tatars and Turks. Later, in the time of Chmielnicki, Russians and Cossacks wreaked havoc – destruction, murder, rape and fire – wherever they went, as they did in all of Red Ruthenia. In this Rohatyn was no exception and fared no differently than the other communities in the area. There are no exact recorded figures of the extent of destruction and murder that was committed there, but in general, the effects of the ravages of Tach VeTat (the tragic years 1648–49) continued to be felt until the middle of the 18th century. What is known is that the damage in Rohatyn was no less than those in the other neighboring areas. This resulted in a great deterioration in the economic condition of the Jews of the area, to the point where on 23 December 1675, even the sejmik of Halicz was impressed and brought up the topic for official discussion with regard to the payment of the head tax by the Jews of Red Ruthenia. It was clear, even to them that the Jews would no longer be able to pay it. The Ukrainian rebellion against Polish rule erased whole communities that had once supplied taxes that were now sorely missing. [33] This finally resulted in bringing the members of the Halicz parliament (sejmik) to petition the national parliament (Sejm) to absolve the Jews from paying this tax. King Jan Sobieski III took note of this request in his directive of 27 July 1694 when he declared, “The Jews of Red Ruthenia have suffered more than the rest of the Jews from the movement of Polish soldiers through their area plus the incursions of the enemy.”

Nevertheless, the Jews were required to contribute their part in paying for the expenses of the war, as provided by the laws of the sejmik of 3 September 1633. This money was used to pay for the salaries of soldiers. Every person without exception had to pay one zloty. In times of general conscription, a tax on lead and gun powder was levied on tenants and tavern owners of the towns and surrounding villages, while the inhabitants had to appear before the army to be drafted in time of attack. And one may very well imagine that in case of invasion, Jews were not exempt from joining the general community in fighting off the enemy; this would include Rohatyn. The economic situation became so bad that people became wild and did what goyim (gentiles) do to Jews whenever they are under pressure. Jewish debtors found themselves pulled off the streets and tied up by their creditors without recourse to the courts. This was too much even for the sejmik, and on 11 December 1675 the sejmik at Sadowa Wisznia ordered their representatives to the Sejm to complain about this anarchy rampant at that time and to do something to eliminate such behavior.[34]

There was a similar occurrence of this nature that took place in the 1620s, when a nobleman, a Skopowski from Rohatyn, grabbed one Yaakov and his wife from Rohatyn and threw them into prison. No reason for this was given, and this aroused the ire of the town, which issued an official complaint against this so-called nobleman as part of its role as the defender of its citizens, even if they were Jews.[34a]

On the other hand, by 1639 the sejmik began to clamp down on Jewish sources of income. It wanted to limit competition with the other inhabitants in business and trade and in public leasing.[35] The sejmik further requested of the Sejm, on 6 November 1713, that it forbid Jewish communities from levying taxes on Jewish tenants in the villages on their own initiative without the assent of the voivode of the area. The sejmik claimed that these kehilah taxes, which went for Jewish community use, were emptying the pockets of the tenants to the point where they were unable to meet their obligations to the owners of the estates.[36]

In addition to the rental of properties, the Jews of Rohatyn engaged in brewing liquor, maintaining taverns, selling beer and wine, peddling, and keeping small shops – which brought in the greater part of their income. At the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, we find Jews primarily engaged in the production of liquor – the brewing of beer and the sale of whiskey, mead, and wine – areas that were open to them in keeping with the rulings of 1633. Jews leased the brewery in the suburb of Babince.

As wholesalers they engaged, to a large measure, in the sale of agricultural products and cattle. As craftsmen they were engaged in a wide variety of occupations – as bakers, tailors, butchers, brewers, and hatters.[37]

Relations between Jewish and non-Jewish workers were correct until around 1663, when the shoemakers' guild complained that Jewish shopkeepers were selling shoes of sheepskin and yellow and red boots in their stores and stalls without notifying them. They felt that this was unfair competition, and therefore, Jews who did so should be required to make a payment of a liter of beeswax for each violation, on pain of confiscation of their goods by the shoemakers' guild. Those who continued to sell black boots should be required to pay the guild ten grzywne on pain of confiscation by the guild.[38]

This was in keeping with the privilege granted to the non-Jewish shoemakers in 1589 and 1633, whereby they could confiscate substandard goods. It also accorded them the right to have first choice in buying leather, effectively enabling them to stifle competition, since the best goods would come from them. However, some Jews continued to ignore these regulations and bought as good a quality of leather as they could obtain as early as they could get it, privilege or no privilege. This aroused the shoemakers' guild to investigate the matter between 1661 and 1664 and resulted in a report that concluded that Jews were indeed buying up first quality leather ahead of the members of the guild, in violation of prescribed privileges. The guild therefore proclaimed that Jews should not be allowed to continue this practice of engaging in the purchase of leather ahead of their non-Jewish competitors. If they were caught in violating this ruling, the shoemakers' guild had every right to confiscate their merchandise, since it was manufactured illegally, and the guilds were to have first choice in purchases of leather.[38a]

From the instructions of the sejmik of Halicz to its parliamentary delegates in its session of 1712–14, we learn that, based on the list of Jews who paid the chimney tax (podymne), Jews were at that time engaged in the sale of wine, in the brewing and sale of beer, in keeping inns, taverns, stalls and stores, as well as being owners of houses in the town square (domy rynkowe) and of taverns in the surrounding villages.[38b]

The economic condition of the Jews of Rohatyn, in particular, as part of the total picture of what was going on in Red Ruthenia, in general, continued to degenerate during the 18th century. Their tax load, normally heavy before the invasions, became progressively unmanageable following them. While the sejmik agreed that there was reason for this condition and indeed the Jews were under great strain economically, they nevertheless, on 9 December 1710, demanded a levy from the Jews of Halicz of 30,000 zlotys per year. However, they agreed to release the towns of Rohatyn, Bursztyn, and Tluste from this obligation for “certain reasons.”[39]

As noted above, the legislators in the district of Halicz – which included Rohatyn – sought especially hard to impose prohibitions and limitations on Jewish commerce, particularly against lessees of government and church-owned real estate. This was backed by the representatives to the sejmik of Halicz, who demanded punishment of those Jews who still held property, on the grounds that they opposed Christianity and therefore had no right to hold Christian property. Those who continued to do so were to be punished.[40] The result was a demand by the sejmik of Halicz, on 20 July 1696, via their representatives, to pass a law in the Sejm of Warsaw to this effect during the time of the interregnum.

This approach dominated the economic policy of the Halicz nobility and was based on the proposition that Jews were “untrustworthy people” (gens perfida), whose only interest was the filling of their own pockets at the expense of the welfare of the republic. [41] In 1718 the nobles of the Halicz sejmik instructed their representatives to the Sejm in Warsaw to demand an end to the collection of taxes by Jews, Armenians, and the like, of customs, national levies, and rental of properties belonging to the nobility. A violation of this should result in the expropriation of the said property. [41a]Even worse was the demand to forbid Jews from exporting salt, horses, oxen, and wine – a large source of income for the Jews of Rohatyn and environs. [41b] They also forbade Jews, by law, from keeping Christian servants.

In addition to attacking the Jewish economy, the goyim of Halicz directed their hatreds at the personal life of the Jewish people and tried to keep them from growing in number. Toward this purpose, the sejmik at the session of 17 September 1736 instructed their delegate to the national Sejm to ask the Sejm assembly in Warsaw to pass a law that would decrease the number of early marriages among Jews. This was to be done by requiring a payment to the government by anyone marrying at an early age of either a certain portion (sortem certum) of their possessions or of their dowry, on threat of a fine.[41c] These economic tribulations were encouraged by the Catholic Church through their anti-Semitic exhortations in church, which fired everyone up against the Jews – as if they needed being fired up.

On 14 August 1752 a complaint was lodged by the sejmik of Halicz in the Sejm, that the Jews were greatly upsetting “the Christians and the merchants in their business, thus wrecking our cities and the royal cities. Therefore, they should be prevented from engaging in all forms of trade with the exception of the sale of textiles and liquor (kwaterka – quarter of a liter) and to embody this in law.”[41d]

In view of this anti-Semitic approach, it is surprising to find the sejmik stressing the need to ease the full brunt of the pressure on the Jews of Rohatyn with regard to the national head tax – from time to time, although not for an extended period.[42] Similarly, in 1725 the tax on liquor was lowered for Rohatyn because of its poor economic condition, attested to under oath by Jews and other people of the town.[42a]

With regard to the head tax, the Jews of Rohatyn paid 715 zloty s and 12 groschen of the 33,857 zloty s levied on the total population of Red Ruthenia in 1717.[43] This caused an uproar by the Jewish taxpayers, who presented a complaint about the criminally unfair division of the head tax on certain communities by some of the people who were in charge of apportioning the head tax. This caused the sejmik at Sadowa Wisznia to decide on 15 March 1717 that the Jews of the towns and villages should gather together in one place and, in keeping with the numbers there, divide the total sum of the tax among those assembled.[44] Then there would be no discrimination against anyone and no reason to complain.

However, the head tax continued to plague the area, and a complaint was again lodged with the marszalek of the regional sejmik in 1734. It was recorded in the town ledgers to the effect that the tax load was unjust and beyond the ability of the inhabitants to pay, since it did not take into consideration the economic condition of the towns and villages, in general, and that of the individual tax payer, in particular. Taking this complaint into consideration, the sejmik ordered the representatives of the Jews to assemble 28 April 1734 in Tarnopol in the presence of the secretary general of the Va'ad Arba Aratzos (Council of Four Lands) and the trustee of the Jewish community, Mordechai (Marek) Rabinowitz. They were entrusted to apportion the head tax equally among the Jews of the towns and villages, without doing injustice to the communities from the point of view of the number of towns and villages, taking into consideration their economic condition. The resulting figures were to be recorded by the secretary general of the Jews and entered into the Halicz and Trembowla ledgers.[45] The result was that in 1734 the Jews of Red Ruthenia were required to pay a head tax of 55,590 zlotys.

In 1750 Reb Yitzchak Yissachar Berish Babad of Brody, the son of Reb Moshe

Ze'ev, was appointed “Trustee of the House of Israel” for the Council

of Four Lands in place of Isser of Zolkiew, as well as acting parnas (leader) for the area kahal. These appointments caused an uproar among the members of the Jewish district

council to such an extent that a number of the communities excommunicated him

and accused him of misusing public funds for his own purposes. They also

complained about the way in which the head tax was apportioned. In 1756 Rohatyn

lodged a similar complaint against

him.[45a]

In the 1760s the relationship of the sejmik of Halicz with the Jews deteriorated even further. In 1764 it instructed its delegates to the national Sejm, during the interregnum and during the session of the coronation, to demand that Jews be forbidden to hold and lease private, national, church, and royal properties; to act as tax collectors, officials, or clerks in tax offices; to sell wine, oxen, and horses; or to sell merchandise from one estate to another; and that the nobility be forbidden to place Jews under their protection.[46]

D. The Sabbatians and the Frankists in Rohatyn

The depredations of Chmielnicki and his hordes as well as the others who ravaged Galicia left their mark not only on the Jewish economy but also on its religious views, in two opposing directions. There were those who wanted a Messiah immediately and tried to bring him to redeem them, and those who were willing to play up to the temporal powers that existed at that time in order to improve their lives, even if it meant leaving their religion to accomplish this. The traditional procedures for Jews trying to bring the Messiah has been to pray, study the Torah, and do good deeds. Later, two new elements were added – Cabala mysticism and the Land of Israel, the Holy Land of the Jews. These last two sources were stressed by Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid, an esteemed Cabalist, who succeeded in convincing over 1,000 Jews to try to come to Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel). Earlier, around the time of Tach VeTat (the terrible years of 1648–49), the opposite also took place. The charlatan Sabbatai Zvi claimed to use Cabala but was unable to and was later succeeded by Jacob Frank, using the relatively same ploys but with even greater ignorance than his predecessor. Both attracted far too many people on false pretenses of messianic promises.

When Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid left, the drive toward mysticism weakened for lack of an outstanding leader. There were some Cabalists here and there in the Carpathian Mountains who attracted followers, but this was sporadic. On the other hand, at this time, there were Jews who approached the Catholic Church to a lesser or a greater extent, some becoming Catholics officially. This could especially be found among lessees of land. The exact number of these apostates is not known. What is known is that King Jan Sobieski, on the recommendation of the nobility, encouraged these practices by granting them properties and even titles of nobility.

This aroused the jealousy of the sejmik of Halicz, and in its session of 27 July 1696 at Sadowa Wisznia, it accused the Jews of deceiving the country and pocketing a good deal of the money that they received, rather than passing it on to the national treasury. Prominent among those accused were the tax collectors Abers and Barnet from the area of Sambor.[47] These accusations by the sejmik were accepted as valid, and their properties were transferred to Daglan Nowiorski of Czestochowa.

As a result of this decision, the nobility of Red Ruthenia cast doubt on the veracity of the Jewish apostates, while the Jews utilized these events in their war against the Sabbatians and the Frankists.

That brings us to the coming of Jacob Frank to Rohatyn. The movement of Sabbatai Zvi spread in Poland, especially in Podolia, Wolhynia, and the parts of Red Ruthenia that bordered on Podolia. Spearheaded by the missionaries of Sabbatai Zvi, it succeeded in gaining adherents in the towns of Malopolska (southeastern Poland) and Red Ruthenia, including Rohatyn. What they officially presented to their audiences was mysticism perverted to suit their purpose. The same was true in the towns of Zolkiew, Podhajce, Busk, Gliniany, Horodenka, Zbaraz, Zloczow, Tysmienica, and Nadworna.[Tr1]

Among the first residents in Rohatyn to join the Sabbatian movement was the family of Elisha Schorr, who moved quickly into the foremost ranks of the movement due to his large family and effectiveness. Elisha Schorr and his sons were joined by Yehuda Leib, the son of Nota Krysa. Even after Sabbatai Zvi died, there remained a large residue in Red Ruthenia that still believed in the Sabbatian claims. They tried to continue to absorb new members by preaching quietly to individuals, so that the rabbinate would not officially be aware of it.

But Schorr was not the only one by any means engaged in this belief in Sabbatai Zvi. There were others such as Moshe David in Podhajce,[48] who claimed to be a Cabalist and miracle worker, and Krysa, whom we have already mentioned, in Nadworna. These three towns in Red Ruthenia, which border with Podolia, were the strongholds of Sabbatianism in Red Ruthenia. Not only did they have the largest number of adherents but also the greatest number of Sabbatian missionaries who spread the beliefs.

In Rohatyn Elisha Schorr and his sons, Shlomo, Natan (Lipman), and Leib were the principal activists. Elisha Schorr was known as a preacher in Rohatyn. He was a descendent of Rabbi Zalman Naftali Schorr,[49] author of Tevuos Shor, which gave him a facade behind which he could hide, since the family was highly respected. Nobody would dream of what he was up to, and since he was accepted as a religious and learned person, people believed what he said. Those who knew better kept quiet.

Elisha Schorr was also in contact with outlying towns in Podolia through his son-in-law, Hirsch Reb Sabbatai, in Lanckorona, who was married to his daughter, Chaja. Chaja eventually was accepted as a prophetess in the Sabbatian camp and became known officially when the activities of the Sabbatians came to light, during the report given by witnesses to the rabbinate, of her sexual aberrations. These included having sexual relations with her brother-in-law, to whom she even bore children, her brothers, as well as with strangers. In this she did not fall far behind her sister-in-law, the wife of Shlomo, whose own sexual activities became well known in Rohatyn – all in the name of religion, the Sabbatian beliefs.

When Frank appeared on the scene, these Sabbatian centers in Red Ruthenia became Frankist strongholds. The elder Elisha Schorr was among the first to join up with Frank whom he considered to be the heir to Sabbatai Zvi. Frank had reached the Dniester River on 5 December 1755. From there, he crossed over to Moghilev, then to Korolowka, his birthplace, on to Jezierzany–Kopyczynce, and from there to Busk. From Busk, he went to the German settlement of Dawidow near Lwow and from there directly to Lwow. In Lwow he settled outside of the city wall in a Christian suburb, but apparently he did not enjoy his stay there and quickly left the area, returning to Dawidow. From there, he came to Rohatyn together with his entourage, at which point he was joined by the Schorr family.

Frank himself related in the year 1756, “I was already engaged in special activities in Brzezany, Rohatyn, and Dworow to such an extent that I turned all of their heads. Even among the Polish magnates, I succeeded to the point where they were all completely befuddled. So you see how it goes with them.”[50] This gives us some concept of the kind of egomaniac he must have been.

After arriving in Rohatyn, Frank began his sexual orgies similar to those that he carried out in Lwow. Among the most active in these orgies was the wife of Shlomo Schorr who engaged in these with a will, all with the permission of her husband. She accepted not only the outside believers but also her father-in-law, Elisha Schorr, and her brother-in-law, Lipman Schorr, who up until then had been more circumspect in their behavior. Now they released all inhibitions “under the influence of Sabbatai Zvi, and even the rabbi from Zbish[Ed5] fell in with them and confessed that he could not forgive himself for his love for the wife of Shlomo.”[51]

The prayers of the Frankists were carried out according to the tradition of Sabbatai Zvi before Frank arrived and continued after his arrival with the addition of the name Jacob next to Sabbatai Zvi – Jacob Sabbatai – according to a witness presented to the Satanow rabbinical court. Rabbi Yaakov Emden in his work, Sefer Shimush, describes how far these people went in their perversion in which they created a divinity of Sabbatai Zvi. They termed him “the true creator, king of the universe, the true Messiah, after whom there is no other anywhere in the universe,” etc.[51a] So far did they go in their perversions. It is not surprising therefore that they were capable of anything.

When Frank left Rohatyn with his followers, he went to Podhajce and then Kopyczynce, where they grew substantially in number. In general, he added new followers wherever he went. By the end of January 1756 he reached Lanckorona where he lived at the home of Hirsch (Zvi), the brother of Leib, son of Sabbatai, and his wife Chaja, the daughter of Elisha Schorr, who served as the center of attraction for the orgies.[Tr2]

The Schorr family was very active in the events in Lanckorona. Once their activities were uncovered, they placed themselves together with Frank under the protection of Bishop Debowski, a rabid anti-Semite, who used them against the Jews. At their instigation, a debate (the first of two) was held between the Frankists and the rabbis in Lanckorona. The protagonists included Elisha Schorr and his son, Shlomo, who together with three more Frankists signed the text of “Accusations and Answers,” around which the debate centered. Elisha, Shlomo, and Krysa probably composed its contents. Frank certainly could not have done it. He was a complete ignoramus who knew how to twist words but used the Schorrs as his “rabbis.”[52]

In other words, the Frankists completed the full gamut to the other side and dropped their religion. When Dembowski died suddenly in November 1757, the Frankists lost their protector, and they followed their leader, Frank, to Dziurdziow, which was at that time under Turkish rule. Frank had already become a Moslem, emulating his predecessor, which is not strange since he did not believe in any religion. Even in his early stages of activity he proclaimed that, as he put it, “I came to Poland solely to destroy all law and beliefs.”[53]

The outstanding religious opponent of Frank in Rohatyn was Rabbi David Moshe Abraham, the author of Mirkevet Hamishne. His descendants were very proud of his war against the Sabbatians and the Frankists. How effective he was in this campaign varies with whom you read. According to the tradition in his family, he is described as “a man of the mighty arm who warred against the band of evildoers and raised the sword of G-d and smote them until they were annihilated.” “Were they not the unclean evildoers who adopted the path of that arch evildoer, Sabbatai Zvi, may his name be erased? And the head of this unclean sect was Elisha, may the teeth of the wicked rot, whose nest was in the town of Rohatyn and was known as Elisha of Rohatyn.”[54]

The descendants of the family further relate that “when this cursed criminal Frank came to our town to lure Jews in the direction of those who had lost their way, the Gaon and author rose up against them, took a spear in his hand and risked his life in order to beat, attack, and annihilate him. This criminal fooled the ruler of the town and inveigled him into chasing the rabbi and the dayan out of town and he, the author of Mirkevet Hamishne, risked his life and did not spare himself from attacking him. And the Al-ty was by his side, and this criminal finally dropped his religion and then all the evil was turned on him, and he could no longer lead any Jew astray.”[55] The fact is, however, that Rabbi Adam's campaign against Frank did not stop Schorr's family from continuing with the Frankists as part of their upper echelon.

Schorr and his family were the most prominent personalities of the Frankist movement during the debate of Lwow in 1759 and after. Frank himself said that when he lived in Dziurdziow, he was always told to go to Rohatyn, on the border of Poland, and he would immediately go there “in order to fulfill the command of his Lord with love.”[56]

Shlomo Schorr and Krysa headed the Frankist faction of the debate. They also carried out the arbitration between the priest Pikulski and the Frankists and signed the petition presented to Primate Lubienski on 16 May 1759. This document was also passed on to the Polish king, Augustus III. It included a petition to have their group settled in the towns of Busk and Gliniany. Although the reasons for the debate began with the relationship between the Christians and the Frankists, after the death of Bishop Debowski, the protective umbrella that had been placed over them was removed.

The rabbis had attempted to open the eyes of the authorities to the fact that the Frankists were not really Christians. Therefore, they requested that one side of their face be completely shaven, resulting in their abuse by many people and causing some of them to run away to Turkey. Among those who ran away was the elder Elisha Schorr of Rohatyn. At that point, the decree was passed officially to persecute them and shave off their beards. But here, too, they received no respite, because the Jews informed the Turks of their perverted ways, and then the Turks oppressed them and took everything away from them. Elisha Schorr was mercilessly beaten and died there, ignominiously, at the end of 1757, “bereft of everything.”[57]

When Frank saw the treatment of his group by the Turks, he decided that they had better leave Turkey. He told his followers to return to Poland, become apostates, and petition Bishop Lubienski of Lwow to accept them into the Catholic religion, because they wanted to “leave the religion of the Talmudists.” This is the background to the infamous debate about the Talmud in Lwow, and that is when Shlomo Schorr and Krysa went to Lwow to quietly arrange the (second) debate there, in retaliation against the Jews for their troubles.[Tr3]

The debate caused troubles not only for the Jews of Halicz, among themselves because of the anarchy that it had introduced there, but also for Jews all over Poland, because it muddied the relationship of the Polish people with the Jews. This became obvious in the decision of the 16 March 1761 sejmik at Sadowa Wisznia, in which they petitioned the Sejm in Warsaw to take extraordinary measures against the Jews. This was based on the results of the debate of Lwow in 1759 which, they claimed, proved conclusively that the Jews do not follow the Torah of Moses and degrade Catholic religious beliefs; their sole purpose is to “undermine our homeland.”

To prevent this, they asked, via the delegates of the Halicz sejmik to the national Sejm, to pass a law forbidding the Jews of Poland and Lithuania the use of their Hebrew religious books and to command them to hand these said books over to the Polish authorities for destruction. In addition, it shall be forbidden to them the use of the Hebrew language in print, which shall be replaced by the Polish language or Latin. To this purpose, it is necessary to close all Jewish printing presses and schools. Furthermore, their prayers shall only be offered in Polish or in Latin and only in front of two priests, and they that resist these commandments should be severely punished.[57a] This was the proposal. How much of this was actually officially accepted by the Sejm of Warsaw is not known.

The leading troublemakers who helped to bring about these problems were Frank and his associates, foremost of whom was the Schorr family. Frank knew how to utilize their capabilities for his nefarious purposes and sent them ahead of him as his messengers to spread the Frankist propaganda. However, in the end, Shlomo Schorr, one of Frank's biggest promoters, brought serious trouble upon Frank and his group, including himself, the result of which was that they were hauled up before the ecclesiastical courts of Warsaw to account for their beliefs.

This came about as follows. Schorr and five of the Frankists who had become apostates were staying in Lwow. The priest Gaudenty Pikulski in Lwow, Schorr's teacher of the Christian religion, was treated to wonder stories about Frank. In the process, Schorr told Pikulski that not only was Frank a miracle worker, but he believed him to be the reincarnation of Jesus. As proof of this he pointed to the fact that Frank had marks on his forehead that were related to the tortures of Jesus.

The Church had been suspicious of the Frankists in view of their behavior, and they decided to investigate what lay behind their conversion, in view of the fact that what they claimed officially and what they really believed did not correlate. Pikulski[Tr4] contacted the Papal Nuncio Serra in Warsaw. Frank was arrested in Warsaw on January 1760. He was interrogated, and then the true beliefs of the Frankists came out in the open. He was therefore tried before an ecclesiastical court that sentenced him and some of his followers to imprisonment in the fortress of Czestochowa. Interestingly, Frank could not talk his way out of this and had to wait until the Russians freed him thirteen years later, perhaps because too many of his followers had made too many incriminating statements during their interrogation. Among those in prison with Frank was Jan Wolowski (Schorr). [Ed6] Shlomo Schorr apparently succeeded in being released before Frank.

From 12 September 1759 to 15 November 1760, which was after the debate of Lwow, forty-eight Frankists from Rohatyn apostatized and became Christians, as did forty-seven in Lwow and one in Warsaw. Among the first to convert from Rohatyn was Eliyahu, age seventy-three, the son of Leib and Feige, also Ze'ev Wolf, the son of Shlomo, who took the name of Andrzej. The family of Schorr who became apostates included Shlomo, his wife and children (Joseph, Jan, Feliks, Michal, Ludwik, Henryk, and Tomasz), their wives and children, and also their relative, Jan Kanti Rafal Wolowski of Satanow. Shlomo Schorr, henceforth Franciszek Wolowski, and his brothers, Natan and Michal Nota, became the “apostles” of Frank and traveled to St. Petersburg on his behalf.

In the year 1768 a group of women from Rohatyn joined the group of Franciszek and Pawel Wolowski. In that year, the Wolowskis sent letters to the Jews of Moravia, Bohemia, and Podolia with a call to accept “the religion of Edom, because only that can save the Jews.” We find the Wolowski children as activists and messengers as well as the “sages” among the group. They composed the leaflets and signed the appeals to the Jewish communities. Later, after Frank's release, when he had settled in Brunn (Bruno), we find a deputation that included Shlomo-Franciszek and Jan and Michal Wolowski being sent to Warsaw by Frank. In December Frank sent Jan and Ludwik Wolowski with two others to Constantinople.[58] Michael Wolowski stayed with Frank in Vienna. In Offenbach, Lukasz Franciszek Wolowski approached Chava, the daughter of Frank, with intentions of matrimony, and she turned him down. Jan, Michal, and Joseph Wolowski raised money in Warsaw and in Turkey on behalf of Frank.

|

|

|

|||

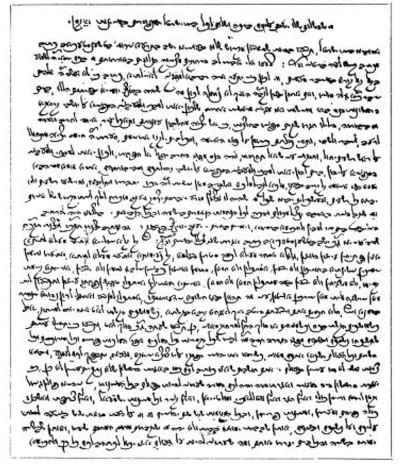

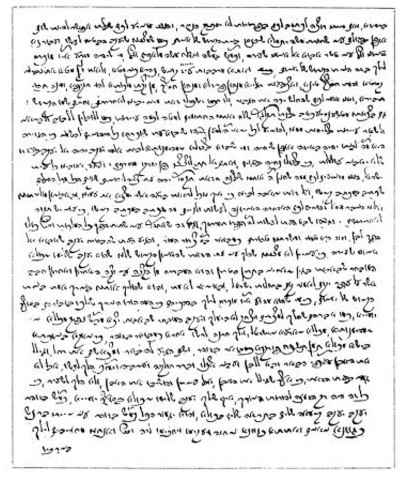

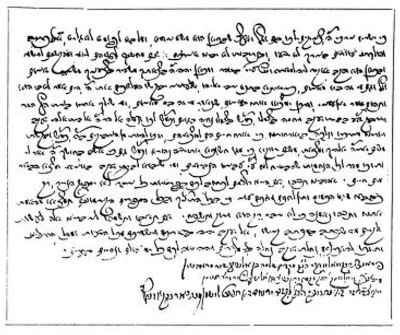

| “A letter in red ink written by the sons of Elisha Schorr of Rohatyn, Franciszek Wolowski (Shlomo), Michal Wolowski (Natan Nota), and Jedrzej Debowski (Yeruham, the son of Hanania Litman from Czernikosnice) to Beit Israel (the House of Israel) dispersed among the Saxon states.” The same letter that was sent to the Jews of Tatria was printed in 1914 by Dr. M. Wishnitzer in the publications of the Academy of Scientific Studies under the name, “A Letter from the Frankists, Year 1800.” In 1921 the letter to the Jews of Hungary was published by Dr. A. Brauer, “Hashiloach”, Jerusalem, Volume 22:38, Pamphlet 5-6. | |||||

When the Schorrs stopped practicing Judaism, they gained fame of a more constructive nature, although not Jewish. The son of Shlomo, Franciszek Lukasz, became secretary to King Stanislaw August Poniatowski. In 1761 he was made a nobleman with a “red ribbon.” The sons of Franciszek were:

The great grandson of Elisha, Franciszek (1776–1844), became a member of the Sejm in 1818 and from 1830-31.[61]He and his sons, Ludwik and Casimir, were prominent among the Polish émigrés in Paris and had no small effect on their political direction.

- Jan Kanti (1803–64)[59] became a well-known lawyer and later secretary of state of Poland and the author of the civil code of Poland. In 1839 he was made a nobleman and received a medal from Czar Nicholas I. In 1861 he became the head of the Department of Justice and a professor and deacon of the Faculty of Law at Warsaw University. He was the author of professional books on studies in law and founded the scientific quarterly Biblioteka Warszawska.

- Teodor became an officer in the Polish army and, in 1839, received the same honors as his brother.

- The same was true of the third brother, Feliks Franciszek.[60]

Ludwik (1810–76) was a well-known economist. In the Polish-Russian war of 1831 he was an artillery officer and then became secretary of the Polish national delegation in Paris. After the Polish revolt, he remained in Paris. From 1834 on, he published a monthly magazine dealing with issues in law together with his brother-in-law, Leo Faucher (who was also of Jewish descent). From 1839 on, he served as a professor. Between 1848 and 1875 he also played an active part in political life in France. Casimir excelled as an officer in several battles in the War of 1831.

The Wolowski family was one of the most diverse of all of the Frankists, with many branches. In the beginning of the 19th century they included tens of male members who were heads of families. They were also the most able of the members of the cult. Many were outstanding in international relations, economics, and Polish literature.[62]In the beginning they followed the spirit and teachings of Jacob Frank, but from around 1830 they began to break away and ceased marrying only Frankists of Jewish descent, intermarrying instead with Polish nobility. The Wolowskis were among the first families to make a determined effort to break away from the Frankist tradition and to intermarry with Catholic families, in order to forget that they were descendants of Elisha Schorr of Rohatyn, the “prophet” of Jacob Frank. In Rohatyn itself, once the Frankists converted to Christianity in 1759, the Sabbatians and Frankists dropped out from the Rohatyn scene.

E. The Rabbis – The Census of 1765

The following were the rabbis of Rohatyn during the period of Polish independence that are known to us:

At the beginning of the 18th century the rabbi in Rohatyn was Rabbi Avraham Leibers, the son of Reb Zalman Leibers, the parnas (leader) of the Lwow Jewish community, a great-grandson of Rabbi Yosef ben Mordechai Ginzburg, rabbi of Ostrog and author of Leket Yosef (Prague, 1789).[62a] In the middle of the 18th century the rabbi was Rabbi David Moshe Avraham, known by the shortened version of his name, Rabbi Adam.[63] He is famous not only as a great scholar but also as a brave warrior against the Frankism that had infested Rohatyn, abetted by the Schorr family. Rabbi Adam is described as one who displayed bravery and spiritual drive “and battled with a mighty arm against the band of evil-doers” headed by Elisha Schorr.[Ed7]

This did not deter the Frankists from presenting false reports about the rabbi to the authorities of the area and demanding his expulsion from the town of Rohatyn. His descendants and the members of the family of the rabbi of Lwow, Rabbi Yosef Nathanson (Shaul), have recorded the difficulties that Rabbi Adam had to overcome in his battle with the Frankist followers.

As a rabbi, Adam excelled as one who possessed a deep knowledge and sense of fairness. In the year 1745 he is recorded as having given his endorsement of Milei D'Avot (Words of the Fathers) printed in Lwow in the year 1746.[64] He exchanged correspondence with the great rabbis of his day, and his responsa (comments) were printed in their works. He wrote Mirkevet Hamishne,[65] which received a letter of endorsement by the rabbi of Lwow, Rabbi Chaim HaCohen Rappaport, and by Rabbi Yitzchak Landau, first rabbi of Zolkiew and later rabbi of Cracow.

The manuscript never reached the printing press during his lifetime and lay hidden for one hundred and fifty years with his family. It came to light when his granddaughter, Teme, the wife of Yechezkiel Goldschlag, visited the Belzer Rebbe, who ordered it to be printed when he learned that she was the granddaughter of Rabbi Moshe David Avraham. He told her that she and the other grandchildren had a duty to print their grandfather's work.

Accordingly, headed by Reb Moshe Nagelberg, the grandchildren carried out the directive of the Belzer Rebbe and printed the book. In addition to Reb Moshe Nagelberg, his sons, Yudel and Itche Nagelberg, his son-in-law, Ephraim Struhl, and Yechezkiel Goldschlag and his wife, Teme, took part in this project. The work appeared in print in Lwow in the year 1895, introduced by the letters of endorsement of Rabbi Yosef Shaul Nathanson, author of Shaul Ve'Meshiv, rabbi of Lwow, and Rabbi Ze'ev (Wolf) Salat, who kept the manuscript of Mirkevet Hamishne in his possession.[66] According to Rabbi Margulies, in his article cited previously, Rabbi Adam also wrote Tiferet Adam and various other religious works that remained in manuscript form. The exact years of his birth and death are not recorded.[67]

Rabbi Adam passed away in Rohatyn and left an extensive family that lived in Rohatyn as well. He was followed by Rabbi Avraham Shlomo, the uncle of Rabbi Yosef Shaul Nathanson.[68] We do not know how long he served as rabbi, but we know that he was the rabbi in 1765, because he signed the census document of the Jewish community of Rohatyn in the name of the kehilah at that time.

Rabbi Adam was followed by Rabbi Yitzchak ben Aharon (Icko Aronowicz), who gave his approbation in 1766 to the Ohel Moed – comments on the portion of the Talmud dealing with holidays written by Rabbi Yosef Yaski, the rabbi of Ulanow, and printed in the year 1767 in Frankfurt-an der-Oder.[68a]

As we know, the Jews of Podkamien and Stratyn were considered as branches of the Jewish community of Rohatyn. Therefore, they were part of the general census of Rohatyn on 14 February 1765 that included the surrounding villages and hamlets.

The national committee enumerated in the town of Rohatyn 742 adults and 55 children under the age of one. In the two towns of Podkamien and Stratyn, there were 200 adults and children and 25 infants under age one. In the forty hamlets attached to the Rohatyn community, there were 295 adults and children and 30 infants under the age of one, making a total of 1,237 adults and children and 110 infants under the age of one.[69] In total, there were 797 people in Rohatyn together with all the children, and when we add the 550 people in the hamlets attached to Rohatyn, we have a total population of 1,347 people. The following are the villages where Jews lived:

| Town | Adults & children |

Infants under 1 |

Town | Adults & children |

Infants under 1 |

| Podgrodzie | 7 | 1 | Lipica Dolna | 5 | 1 |

| Ruda | 5 | 1 | Âwistelniki | 10 | -- |

| Kleszczowna | 8 | 1 | Szumlany | 19 | 1 |

| Firlejow | 6 | -- | Slawentyn | 29 | 3 |

| Korzelica | 7 | -- | Sarnki | 7 | 1 |

| Hulkow | 5 | -- | Zolczow | 12 | -- |

| Janczyn | 8 | 1 | Danilcze | 4 | 1 |

| Potok | 5 | -- | Czesniki | 13 | 2 |

| Czercze | 11 | 1 | Lopuszna | 5 | -- |

| Soloniec | 5 | 1 | Dusanow | 5 | 1 |

| Wierzbolowce | 3 | -- | Kutce | 4 | 1 |

| Putiatynce | 6 | 1 | Zalipie | 2 | 1 |

| Luczynce | 9 | 2 | Psary | 2 | -- |

| Babuchow | 5 | -- | Doliniany | 4 | -- |

| Koniuszki | 9 | -- | Dehowa | 4 | -- |

| Ujazd | 2 | 1 | Zalanow | 7 | -- |

| Obelnica | 5 | -- | Dziczki* | 7 | 1 |

| Kunaszow | 4 | -- | Bienkowce* | 11 | |

| Zelibory | 3 | 1 | Fraga | 4 | 1 |

| Lipica Gorna | 3 | 1 | Dubryniow** | 22 | 4 |

Dr. M. Balaban, Spis Zydow i Karaitow ziemi halickiej i powiatow trembowelskiego i

kolomyjskiego w r. 1765

(Census of Jews and Karaites in the Halicz region and in the districts of

Trembowla and Kolomyja in 1765) (Cracow 1909): 10–11.

We have no details on the breakdown of occupations of the Jews in Rohatyn during this time. From the census that was made of the Jewish towns of Jazlowice and Zaleszczyki for the year 1772, two towns that are similar to Rohatyn in their makeup, we can, by comparing them, make a breakdown of the occupations of the Jews of Rohatyn – which were, as a matter of fact, no different from the others. According to the census there were:

| Occupations |

Jazlowice Population 968 Employed |

Zaleszczyki Population 859 Employed |

| Silk Merchants | 2 | 1 |

| Storekeepers | 10 | 25 |

| Town Bartenders | 27 | 25 |

| Barber-Surgeon | 1 | -- |

| Goldsmiths | 2 | -- |

| Coppersmith | 1 | -- |

| Tailors | 11 | 17 |

| Bakers | 3 | 3 |

| Butchers | 2 | 6 |

| Tavern Lessees | 26 | -- |

| Other Lessees | 7 | 7 |

| Middlemen | 2 | -- |

| Servants | 19 | 25 |

| Bathkeepers | -- | 2 |

| Aged or Sick on Pension[70] | 14 | 2 |

| Unemployed | 46 | 36 |

From these numbers, we learn that from the Jewish community of 968 people in Jazlowice, there were only 60 families where the head of the family had a trade. There were also 14 aged and sick, 46 unemployed, and 19 men and 14 women who worked in housekeeping and maintenance. Similar figures were to be found in Zaleszczyki. Of 859 people, there were 79 regularly employed, 25 men and 10 women working in homes. There were also 2 people listed as sick, and 36 listed as unemployed. We may assume that the same figures more or less existed in Rohatyn with one difference – the number of trades.

During the last years of Polish independence, starting in 1763, Rohatyn was forced to endure the invasions and passages of foreign soldiers, especially those from Russia and later from the invading troops of the Confederation. This ended only when Poland ceded all of the Halicz district to Austria after the first division of Poland in 1773.

F. Under Austrian Domination

Rohatyn was included in the district of Zloczow, which was headed by Starosta Tannhauser. Zloczow was raised to the rank of district capital; this correlated with the beginning of the development of the district. In contrast to the typical Austrian bureaucrats common in Galicia who stressed pan-Germanism, Tannhauser was a Polish sympathizer and was more interested in stressing the development of a stable economy. He saw to it that taxes were eased and looked for ways to improve the socioeconomic condition of the population. In the first years of the Austrian conquest the conditions of the Jews of Rohatyn were difficult because of the new conditions introduced by the Austrian government that differed from those that had existed under Poland. During the first four years, the organization of the Jewish kehilah remained substantially the same as it had been under Poland. However, after the proclamation of the ordinances concerning Jews (Judenordnung) of the Empress Maria Theresa on 16 July 1776, the ordinances of Joseph II of May 1785, and the tolerance ordinances of 7 May 1789, a new permanent organization of Jewish affairs was established in Galicia that brought about decisive changes in the community life of the Jews.

The Jewish community (kehilah) was organized according to the ordinances mentioned. At the head of the committee in Rohatyn, as in all other medium size and small communities, there was a community council (va'ad kahal), composed of chosen heads with very limited powers, that was required to obey and to submit to all the demands of the district authority (Kreisamt). The kehilah was responsible for collecting all of the taxes that were levied on the Jews, for providing soldiers to the army, etc.

According to the Jewish ordinances of the year 1776, the community council was composed of six members. According to the rulings of Joseph II, the council was reduced from six members to three, except for Lwow and Brody, which had seven members. The right to vote “actively” was given to heads of families who paid a Sabbath candle tax of seven or more candles during a full year before elections, and the right of “passive” voting applied to heads of families who lived in Rohatyn, had a good name, knew how to read and write German, and paid a Sabbath candle tax of ten Sabbath candles during a full year before elections.

In addition to heads of the community, heads of the burial society (chevra kaddisha), beadles, managers of the hospital, and auditors were elected. The officials of the community included a secretary (scribe), a caretaker, cantors, beadles, ritual slaughterers (shochetim), and gravediggers. The direction of religious matters was placed in the hands of a rabbi who was elected for three years by the electors of the community. This state of affairs lasted until the period between 25 August 1783 and 23 May 1784 at which time the central government in Vienna no longer recognized the jurisdiction of the Jewish communities and the rabbinical courts. After the regulations of 1785 the office of community rabbi (Rav Hakahal) was abolished and only the appointment of teachers of religion (Religionsweiser) and cantors was permitted. Every district was given its own district rabbi (Kreisrabbiner), and in Rohatyn, there was officially only a teacher of religion who held all jurisdictional powers.

According to the regulations of 7 May 1789 the leaders of the Jewish communities received their salaries from community funds deducted from taxes. This resulted in a rush for these positions, as they were a sure source of constant income. The desire to receive the honor of being head of a Jewish community (parnas) was understandably strong right from the beginning of the establishment of Jewish autonomy in Poland, as this was the most prestigious office among the Jews there.

Even in Rohatyn a great deal of activity took place during the elections of the Jewish kehilah. These were accompanied by conflict, complaints, and secret accusations against candidates who were accused of levying taxes illegally. It was claimed that they placed the main burden of taxation on the weakest class of the population while sparing themselves and their families.[70a] This resulted in not a few explosive reactions as well as false accusations to the authorities, based on fictitious concoctions of their imagination. Every Jew required to pay taxes had a tax ledger (Steuerbücher) that served as his passport of membership in the community. If his ledger was taken from him because of any differences with the kahal (council) or any other violation, his name was erased from the official roster of the members of the kehilah. More than once these so called violations were fabricated by the heads of the kehilah in order to ostracize someone whom they did not want or like for any reason.

Such things were recurrent in Rohatyn during the years 1781–94 and during the 1820s,[71] as we can see from the records in the archives.

The salary paid to the rabbi of Rohatyn was eighty-six florin per year plus the free use of the house in which he lived during his tenure.[72] Rohatyn under Poland was a possession of the crown, in contrast to the other towns of eastern Red Ruthenia that had established Jewish communities. This facilitated the sale of its property by the Austrian government. Indeed, a short time after the Austrian conquest, it began to sell Polish royal property, which included towns, and by 1783, it had sold 5,000,000 florin worth of property. In this way, the ruling government tried to promote the development of towns. The residents saw this action as a sure means for the removal of Jews, or at least a reduction of their numbers. However, after investigating this project, the Austrian government concluded that such a move would accomplish just the reverse of what it was intended for and wreck the towns, since other than Jews, there was no established sound economic factor that could maintain the economy; Jews were the essential economic pipeline of the towns.

The Austrian government also recognized that there was an element of cruelty in their suggestion and stated, “It would appear that this contains within it an element of cruelty even if the circumstances would seem to make it necessary, unless they are willing to forego the improvement of the towns.”[73]

At the beginning of the conquest, Rohatyn was included as part of the district of Zloczow and administered by the chief official Tannhauser, a man who was interested in the welfare of the inhabitants. He was an able administrator who put in effort to ensure that all taxes were paid on time, and indeed, in his district, this was the case. He recognized the contributions of the Jews to the economy and opposed their being driven out, either from his district or from the properties that they were renting, because such an act would cause an economic vacuum. Later in the '80s, Rohatyn was transferred to the district of Brzezany.

Taxes and Other Payments:

In 1774 the Austrian government raised the head tax in Poland from thirty kreuzer to one gulden. This tax was made part of the Jewish Ordinances of 1776, under the name of a

tolerance tax (Toleranzsteuer), rather than a head tax, in the sum of four gulden per family. In addition to this, it levied an income tax in the sum of four gulden per Jewish family and a marriage fee, levied according to the wealth of the

family. Taxes were first apportioned by the Austrians according to communities.

This apportionment of taxes was divided among the communities, which in turn

divided it among their members. Then, in the year 1784 Joseph II of Austria

abolished the income and property taxes and replaced them with the following:

Opening a new synagogue required one payment.

Opening a new Jewish cemetery required a payment of two hundred gulden upon its opening and one hundred gulden every year thereafter.

A census fee of fifty gulden per year.

In 1797 the real estate tax was abolished and replaced by the Sabbath candle tax and a supplementary tax (Ergänzungssteuer). When not enough taxes were realized from the property tax and kosher meat tax, the difference was covered via a supplementary tax.

A special tax (Extrasteuer) was levied on Jews in place of the income tax that was collected from Christians.

Every Jew and Jewess was required to pay the candle tax with the exception of

With the enactment of the kosher meat tax, which was tied up with exorbitant profits, strife broke out in all of the communities. Collection of these taxes was the official monopolistic prerogative of tax collectors who were granted powers to determine the size of the kosher meat tax at their discretion and to limit the right of slaughtering meat to certain butchers, resulting in the raising of the price of kosher meat. Since these butchers worked hand in hand with the tax collectors, the customer had no way of knowing what the price of meat would be at any given time. The butcher could always claim that the rise in price was due to the rise in taxes, which were subject to sudden change. This situation aroused the ire of the Jewish population, especially of the poorer families, who were being incited by the butchers who had been refused the right to sell kosher meat, thus wrecking their livelihood. This problem existed in all communities and engendered hatred and bitterness among the Jews of the community.

In addition to the relatively large amounts of money to be paid in taxes, there were also the methods employed in collecting the taxes that aroused the anger of the people in no small measure. Thus, when people fell behind in their payments, confiscation might be carried out by soldiers on horseback and police who seized private belongings and furniture without pity. Then too, there was the element of graft related to such matters. Most tax collectors were parnassim who received the full ire of the community, thus deflecting it from the government that had levied the exorbitant taxes.

According to figures arrived at by the commissioner of the district of Zloczow

in the year 1806, each Jewish family paid the following for basic Jewish taxes

alone:

Candle tax - six florin per yearThis situation caused problems for the head of every family.

Meat tax - up to fifteen florin per year

Tolerance tax - four florin per year

Special tax - five florin per year.

Adding up to a total of twenty-eight florin per year.[74]