|

|

|

[Page 134]

by Yosef Mazor

Translated by Ron Skolnik

The origin of this extensive family, which with the passage of time did disperse across many lands, is from the region of Mogilev in Central Russia. R' Yisrael Jaffe[1] was the son of Shneur Zalman Aharon Jaffe, a merchant from the city of Senno, in Vitebsk Province, and Chaye-Feige née Machnik. Yisrael was the firstborn and he had another two brothers and two sisters. He was an illui [child prodigy, generally referring to Talmudic scholarship], studied under the Rebbe of Lubavitch and was ordained as a rabbi and dayan [religious court judge]. In 1892, he was invited to serve as rabbi in the city of Bălţi. At first, he hesitated whether to accept the appointment and settle down in a remote region, far from the great centers of Torah, in a city most of whose Jews were simple and stout people, but not talmidei chachamim [Torah scholars – literally “students of sages”] or intellectuals. Ultimately, he gave in to the pressure that was applied on him and accepted the appointment. He remained a rabbi and dayan in Bălţi over the course of 42 years, until his dying day on 5 Tevet 5686 [December 21 or 22, 1925].

R' Yisrael Jaffe and his wife, Miriam-Esther née Gillerson (1853-1941), she too a native of Senno, daughter to a Lithuanian family, had six children, one daughter Sarah–Devorah (1871-1942), Yitzhak-Elimelech (1872-1942), Chaim Rafa'el (1874-1942), Menachem-Mendel (1876-1946), David (1878-1942), Yerachmiel (1893-1974).

In his years of tenure in Bălţi, R' Yisrael was essentially in charge of the fitness under Jewish law of the lives and manners of the Jews there. He needed to resolve problems of day-to-day life, counsel and make rulings under Jewish law, settle various disputes that broke out among the people. Whereas all his free moments of time were devoted to studying Torah and writing commentaries on the Holy Scriptures and composing responsa. His room was full of Holy books alone. And within his large library he would spend most of the hours of the day. He would not be seen strolling the city streets. Only seldomly would he include himself in social occasions, and he, being introverted and secluse, would leave all the practical problem-solving and breadwinning concerns to his wife. No one heard him raise his voice, he kept away from any quarrel or askanut [public activism], while he would, out of concern for din tzedek [lawful justice], but without exacerbating matters, settle amicably, with moderateness, the problems of the Jews who would appeal to him to adjudicate on one dispute or another. Whereas he would turn away and cast aside those who would come to him and ask him to manifest “signs and wonders”, to operate with “mysterious” powers, in the manner of certain Hasidic rabbis, and vehemently refuse to accede to their requests. He managed during his life to bring only one book of his writings to print, “She'arit Yisrael” [Remnant of Israel], which his son Yitzhak-Elimelech took with him abroad and had printed there at his expense. Whereas the remainder of his writings, which took up considerable space in his study, were left without a savior and, after the outbreak of World War II and the occupation of Bessarabia by the Soviets, not the smallest remnant of them was left.

In the memory of all his close associates and his acquaintances, an image of him remained embedded as an intangible spiritual being of a talmid chacham, erudite

[Page 135]

and keen, and at the same time modest and good-natured, a man who was far from the real ways of the world, immersed in the world of Torah and contemplation.

His children were traditionalists, observant of practical commandments, but their path in life was different. Yitzhak-Elimelech tried his hand at commerce and industry, and he was the most successful of all the children in the world of practical action. At first, he was a grain trader, and in time he established a flour mill of his own, which was one of the largest and most advanced in the city. Out of a respectful attitude toward his father the rabbi, he built a special wing in the courtyard of his house and erected a synagogue there, where Jews would pray daily, on days of Shabbat, and on Jewish festive days. This synagogue remained standing intact for many years after the death of R' Yisrael, and it appears that only in the days of Soviet rule did it close.

Yitzhak-Elimelech was not just a successful industrialist and merchant, but also a person with foresight about the future. He was a devoted Zionist and, as early as the 1930s, dreamt about liquidating his business dealings in Bălţi and transferring them to the Land of Israel. In the early '30s, he sold a plot of land that he had in Czernowitz, transferred the money to the Land [of Israel], and in 1934 laid the cornerstone for his house in Haifa, on 15 Jerusalem Street. His son-in-law Mendel, the husband of Rivka, dwelled part of his time in the Land and saw to the building's construction. But the throes of uprooting from Bălţi were difficult and tortuous, and in the meantime Yitzhak-Elimelech became ill with arteriosclerosis and was no longer able to carry out his plans. At the outbreak of the Second World War, only Mendel was to be found in the Land, whereas all the rest of the family members were in Romania, to where they had moved on the eve of Bessarabia's occupation by the Red Army. In October 1940, after difficulties and mishaps, all the members of Yitzhak-Elimelech's family reached the Land of Israel. And these were essentially the only remnants of the extensive Jaffe family who survived. Sarah, Chaim Rafa'el, Menachem-Mendel, David, and most of the members of their families were killed in the Holocaust, fell at the hands of Romanian murderers when Bessarabia was conquered back by the Romanian and German army in 1941, or died from diseases and epidemics within Russia.

In the 1930s, on the streets of Bălţi it was possible to encounter the four brothers of the Jaffe family, sons of R' Yisrael, all of whom were men of stature, thickly-bearded, wore long black kapotas [greatcoats] and were involved in commercial life, and several of them in public life as well. Chaim Rafa'el had a [plant] oil factory on the outskirts of the city, but he was given over almost completely to public affairs, was widely known as a talmid chacham and an honest man who was highly sought after as an arbitrator, whenever there was some hard to resolve dispute. David, likewise, was a merchant, establishing a factory of his own for refining [plant] oil, but he was not exceedingly successful in his business dealings.

Menachem-Mendel dwelled in the town of Marcushelti, near Bălţi[2], had an agricultural machinery store, and even represented foreign firms, and would visit Bălţi frequently and would stay at the home of his eldest brother. Only Yerachmiel “broke out” of the traditional framework, though in his youth he, too, studied in a yeshiva and was ordained to the rabbinate; in time he set out abroad, acquired a secular education and a technical profession, and even though he came back and started his family in Bălţi, his one foot was planted in the traditional Judaism world and the other in the secular modern world. His thirst for knowledge led him to study various subjects. He was not “master of one trade”. In his youth, he studied pharmacy and bookkeeping, after he received a matriculation certificate in Odessa he began to study engineering, first at the universities of Kharkov and Odessa, and afterward in Belgium (in Liège and in Ghent), there he also received his certificate as a mechanical engineer. And in old age, after he had gone into retirement, he again did “professional retraining”, studied law, and thanks to his vast amount of knowledge in the sources of Hebrew law, he was accredited as an attorney when he was about seventy years old. And even though he did not get to work in his new profession, he did not cease taking an interest in all the goings-on and happenings in the field of law, he would keep up to date with the professional literature and the volumes of court rulings, and he would bestow his advice, not for personal gain, to anyone asking. At the same time, he continued to work at “the soya board” as long as his health had not grown weak.

Engineer Mendel Jaffe

He was born in 1900 in Czernowitz. He studied engineering and received a civil engineer's degree. He specialized in the construction of roads and bridges and was employed in this role by the Romanian army and in his civilian life by the Bălţi district public works department until 1929.

In 1930 he married Rivka Jaffe, his cousin, the daughter of his aunt and of Itzik Melech Jaffe[3], and they had two children, Yisrael and Uri[4].

[Page 136]

Mendel decided to immigrate [lit. “go up”] to the Land of Israel, and was the chalutz [pioneer] of the family.

Mendel was the image of a hardworking man, diligent and punctual, able to endure and one who makes do with little. He was able to stay on the road and in the field together with the simple common laborers.

In spirit, he was a chalutz type in the full sense of the word. Shy and retiring, he hated to stand out, was not fond of elbows.

He was handed, by the family, the job of putting down roots in the Land of Israel and establishing a foundation for a home for the family. And indeed, he established a home on Jerusalem Street in Hadar HaCarmel [a neighborhood] in Haifa, which in due course served as a refuge for the family that had managed to escape from the Bălţian hell prior to the Russians' arrival and before the coming of the Holocaust.

He continued to work for “Solel Boneh”[5], at the “Shikun” [“Housing”] company, and he built up entire regions in Haifa and the north. You could say that he built up the Land – literally.

He passed away from a heart attack, while working, in 1965.

|

|

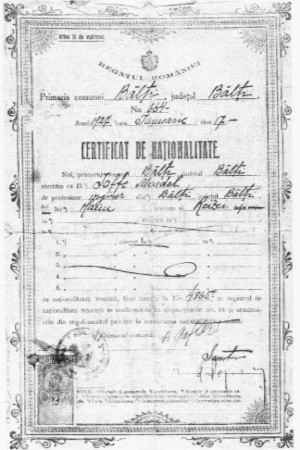

| Romanian certificate of naturalization |

[Page 137]

|

|

| Rivka and Mendel Jaffe |

|

|

| Rivka Jaffe's Hebrew Gymnasium matriculation certificate |

[Page 138]

|

|

accompanied by the Jaffe family From left to right, Mendel Jaffe, Itzik Melech Jaffe, Mendel Massis, (unknown woman), Rivka Jaffe |

[Page 139]

|

|

| Chaim Rafa'el Jaffe and his family, Chaya, Shlomo, Mendel, Itka (the father of the family and his wife were murdered by the Moldovans in the Kosauts forest during the Holocaust) |

[Page 140]

|

|

| The Jaffe family on the balcony of Elimelech Jaffe's house (1937). The child in the foreground of the picture – A.B. Jaffe. |

|

|

|||

father of the Jaffe family in Bălţi |

[Page 141]

|

|

| The Jaffe family, photograph from the beginning of the 20th century |

Translator's footnotes:

by Z. Heinichs

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| Bernard Walter |

Bernard Walter was not the regular community worker, with fixed social-political concepts. His “idée fixe” was to help a Jew, to argue for his benefit before the Romanian police when he was arrested for political reasons, to intervene at the town authorities or the military authorities for a single child of poor parents etc. In this respect – trying to persuade the authorities in favor of the Jews – Walter had no equal. His “clients” were of many kinds: Zionists, Bundists, communists and others. He was always ready to help, always ready to do a favor. And it must be noted, that he did all this freely, without expecting any reward. Sometimes he even added from his own pocket what was needed. Everybody remembers Walter's help when the citizenship of the Jews was questioned and investigated, according to the new Goga-Cuza laws.

B. Walter was born in Bucharest. In 1918 he came to Bălți with the Romanian army. He remained in Bălți and immediately began his blessed and unique work of helping Jews.

He began with the Home for the Aged and improved the living conditions of the aged residents. He ensured the supply of food and clothing for the Talmud Torah pupils. He organized the Jewish Merchants Committee. He helped the Jewish Hospital. He was chairman of the “Chamber of Commerce and Industry” and helped the Jewish small businessmen. In 1929, he was elected aide to the Mayor. He was also active in collecting money for the support of the illegal Aliya. In 1941, when the Romanians occupied Bălți, they arrested 20 Jews – the leaders of the community and other prominent people, among them Walter. By a miracle, following some intervention from Bucharest, he was saved minutes before all others were shot to death. And another interesting play of fate: In 1942 Walter acquired a ticket for the ship Struma to make Aliya to Eretz Israel. Here another miracle occurred: He was arrested by the Romanians before he could board ship, but was soon released. From 1951, in Eretz Israel, he was active in the Organization of Former Residents of Bessarabia.

by Dr. M. Gafter

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

Moshe Krasyuk was a prominent “house-owner” [Baal-Bayit] in the town Bălți, not only because of his tall stature and beautiful beard but also for his activity in various Jewish cultural and social institutions, such as the Talnud Torah, the Jewish High-School [Gimnasia], the Community etc. In 1922, he was chairman of the Parents' Committee of the High-School.

Moshe Krasyuk prayed in the “Slaughterers' Bet Midrash.” After his death, a Prayer Quorum [Minyan] was organized during the High Holidays [Yamin Nora'im = Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur] for his neighbors, in his house on Chatinski Street. It was done with the help of the Youth Association Committee, where his son was a member. The volunteer cantors were Dr. Gendelman and the pharmacist Roizman. The income from this Minyan was used for social purposes.

Moshe Krasyuk's wife, Yente, was also known for her charity work and philanthropic activity in town.

Moshe was a devoted Zionist, visited several times in Eretz Israel and even bought a plot of land in Holon. He accomplished a great deal for Zionism and for the Jewish population in Bălți. He possessed personal wealth as well, occupied important places in the institutions he worked with, and gained respect during his life and also at his funeral in 1924.

Moshe owned land, which he leased to the farmers in the region, and was respected by all the people who worked with him.

His sons were tall, energetic and socially active, like their father and mother. Some were also active Zionists and observed Jewish law as their parents did.

Dr. Fishel Krasyuk studied medicine in Switzerland, practiced in Bălți. He taught Hygiene in the local high-school. He was a Zionist – Tze'irei Zion – and a member of the Parents' Committee.

Dr. Chaim Krasyuk studied medicine in Germany, practiced in Zaguritze, Kishinev. In Zaguritze he was the chairman of the Revisionist-Zionists.

Shalom Krasyuk was a land-owner and industrialist.

Yechiel Krasyuk was a land owner as well; the Soviets have deported him to Siberia. Isak Krasyuk was a pharmacist.

[Page 145]

Aharon was a land owner and a Zionist, a founder of the Second Talmud Torah. Was deported to Siberia and died there.

Leib immigrated to Argentina as a young man, married a Bălți girl, the daughter of the photographer Maltz, died young of a heart-attack.

The daughter Fanya Krasyuk married Dr. Gandelman.

|

|

| The Krasyuk Family |

by L. Staviski (Goichman)

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

When I try to remember my childhood days in Bãl?i [Beltz] I get the impression that I am seeing everything through a thick veil of fog, and from this fog figures appear, beloved but blurred, and I am not always able to connect them with the present reality: our little town, full of Jews of all social strata, with its public institutions, the City Hall, the Police Headquarters in mid-town, the public park named after Queen Maria, the church with the red roof in Gothic style, the bells ringing while we children would look at the person pulling the ropes, who would seem to us from the distance as small as a dwarf. I remember the days before we had electricity: at dusk a man would go through the streets and light the street lamps. Water carriers would bring water to the houses, and the traffic in town was by carriages pulled by horses. We had a horse named Masha. When Masha was hungry she would leave her stall, come to the house and knock on the door with her head – then we knew that she was hungry. In the winter we had a sleigh and the same Masha would pull it, full of children and driven by my older brother.

Jewish life, as I remember, was comfortable. The government was tolerant toward the Jews. The Jews were allowed to establish their own schools, where the pupils learned Hebrew and twice a year Government exams were held, so that the diplomas became official. The graduates who passed the Matriculation Exams were accepted to the universities. I and my two brothers went to the Hebrew School, called “The Hebrew Gymnasia” [High-School]. The atmosphere was warm, Jewish, with Zionist orientation. Twice a year, on Chanuka and on Purim, we had parties with the participation of all the children and their parents. I think that anyone who remembers our Jewish High-School feels a shudder of warmth and nostalgia in his heart.

The Jewish Community took care of all the needs of the Jews, in particular the poor. I remember that when a Jewish girl from a poor family was about to get married, the Community would collect money for her dowry. My father was once elected head of the community.

Elections were held every few years. There were two parties: the Liberal Party and the Peasants [Tãrãnesc] Party. The Liberal Party had a bourgeois orientation, while the other was democratic. My father was a member of the Democratic Party and every time the Peasants' Party ruled, he was appointed at a public office; once he was elected Deputy Mayor. But his main public activity and his main work, which earned him his livelihood, was his work at the Jewish Bank, named “Lei und Spur Kasse” [Loan and Savings Fund], which provided loans and saving mainly for Jewish craftsmen. Every three years there were elections at the Bank and my father was elected every time. I remember

[Page 147]

that the craftsmen in our town were very poor and worked very hard for the sustenance of their families. Once, the time came to pay the loans and long lines formed at my father's office – to ask him to postpone the date of payment. My father was always willing to help, out of his understanding and his warm and good heart, and there was no end to the thanks and blessings he received for that.

The bank hosted a library and children would come to change books. When the end of the month came and it was time to pay the library dues – a child whose parents were unable to pay would go to my father's office and ask for a delay; my father would give him a “note” to the librarian and she would give him the book he wanted.

My father had two additional tasks: he was the local agent of the JOINT Society (whose purpose was, among others, to help Bessarabia Jews to work the land and become farmers); he would travel to the villages and many times he would take us children along. He ownwd a vineyard, an orchard an a wheat field and he would travel from village to village and teach the Jews agriculture, while also distributing among them various strains of agricultural produce.

His other job was with an American company whose name I don't remember; in its framework he would help Jewish people to immigrate to the Unites States. My father had a warm Jewish heart and was also a Zionist, but not an active one. In the evenings he would read to us from the Jewish newspaper about the riots and pogroms in Germany as Hitler began to rule and was crying while reading. He dreamt about a Jewish State with Weizman as king.

|

|

| The A. Goichman Family |

as related by Eng. Yakov Gefter

I. Mazor

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

Yakov Gefter, the son of R'Avraham Gefter, was one of the leaders of the community during many years, a witness to the Holocaust, one of the first pupils of the Hebrew High-School [Gymnasia], one of the first Hebrew teachers (volunteer) in Bessarabia, graduate of a university in Belgium, made Aliya in 1934, one of the pioneers of the textile industry in Eretz Israel. He relates the following about the Gymnasia (Jewish High-School):

Most of the first teachers were not Jewish. Yakov graduated in 1926. Since it was not at all easy for Jews to be accepted at the Romanian universities, he intended to study abroad, as did the children of the rich Jews. The day before he was about to leave – relates Gefter – on a Shabat morning, the teacher Schwarz and another teacher appeared at his house. “Well Yasha, we didn't come just to say Farewell. We came to tell you not to go. We decided that you should stay another year or two and work in the area of Jewish education. New schools are about to open in Bessarabia and we ask you to be not only a teacher, but the principal of one of the schools.” This was a service to the Jewish State, before the State was established – a service to Jewish education in the Diaspora.

Indeed, Yakov obeyed their decision; he postponed his journey and joined the Jewish Education System. He was assigned work in a small town in Southern Bessarabia, where some 90 Jewish families lived. In the framework of the government school, a Hebrew section was opened, in the afternoon. Yakov Gefter worked there one year, as principal and teacher of Hebrew. In the second year a Hebrew school was opened in Ismail (Southern Bessarabia) and Yakov Gefter worked there as well. From his memories:

The first pupil of the school was Yakov Greenwald. He made Aliya to Eretz Israel and was the first general manager of the Telephone Services in the country. The Avraham Gefter family belonged to the upper middle-class. The father, Avraham Gefter, was in the commerce and industrial businesses. He owned an oil factory, located not far from the school. But he had little success, and in fact he was not a wealthy man.

The Gefter family had four sons and four daughters. The children were aware of the economic difficulties of their parents ad all gave private lessons, helping to balance the family budget. It also enabled the children to continue their studies.

I asked how it was possible to explain the rare phenomenon of opening a Hebrew high-school during the time of transition, at the end of the Russian Revolution.

[Page 149]

Yakov explained that it was the initiative of several people, who were captured by the idea and were pushed to the activity of erecting a Hebrew high-school by the reality which limited the possibilities of the Jews to enter higher education due to the “numerus clausus” laws. As an illustration, Yakov Gefter told the following story:

In the school-year 1917, there had remained just one place for a Jewish student in the local high-school and there were two competitors for it – one of them was his older brother Moshe and the other was Leonia Baron. Since both passed the exams with the same grades, the school management decided to draw lots. Both mothers prayed for their own son to win. Yakov, who was still a young child then, remembers that suddenly Mrs. Baron burst into their home, embraced his mother and shouted happily “Your Moishe'le won!” This situation convinced my father that the establishment of Hebrew schools, independent of the government educational system was an urgent necessity. He called an assembly of several municipal leaders, Zionist Jews. Yakov remembers well that Saturday afternoon – he was sitting near the heater listening to the discussions: R'Avraham presented the question: “What are we going to do so that our children could learn?” – and in his juicy Yiddish he gave the answer himself: “You know what came to my head? We are going to make our own Jewish High-School.”

The doubters, as usual in such cases, did not believe it was possible. One asked: “What about the permit?” Another said: “We will not have enough children.”

R'Avraham replied that it will be possible to get a permit, and as to the children – he began counting the children of the people present at the assembly and of other families.

|

|

| The Avraham Gefter family |

[Page 150]

The group announced that they will act as a “Parents Committee” and Avraham Gefter decided to go to Odessa to obtain the necessary permit to open a High-School, a Hebrew Gymnasia in Beltz. He was still wearing the traditional Jewish attire, the Kapota, but this did not stop him from appearing before the higher authorities to fulfill his mission in the matters of the Jewish people.

The Committee published an announcement in the Jewish press in Russia (the newspaper Hayom [Today] of 30 June 1917) and the paradox was that the announcement, asking for teachers of Hebrew was written in Russian.

R'Avraham indeed went to Odessa and brought the permit. Then he went to Grodno, where there was a Hebrew Teachers College and brought teachers of Hebrew and of Jewish subjects. The Committee leased the building of the Government school for the afternoons, to conduct the Jewish studies. Later they bought their own building. The members of the managing committee of the school were Leibush Galawati and Chaim Refael Yaffe. As secretary they elected Mr. Gulka; later Gulka became the treasurer and a Christian by the name of Tachenko was appointed secretary.

R'Avraham Gefter was appreciated by the teachers as well as by the parents. When he retired from his job he was given the title of Honorary Chairman of the High-School and received a photo of all the teachers, in an elegant leather frame.

Yakov tells the following about the origin of the family:

The father, Avraham, was born in one of the villages in the neighborhood of Beltz. The mother, Chasia, was the daughter of Yankel Slishtzors from Britchan [Briceani]. The father was not ultra-religious but he was a Jew of a national-Zionist outlook who kept the Commandments. He was totally devoted to Hebrew education, which he considered the main goal of his life.

Yakov remembers their first apartment in the old section of the town – the reason his father was so attached to the “Rabbi's Bet Midrash” as they used to call it. Later they lived in a spacious apartment near the artesian well, not far from the Post Office. As mentioned, R'Avraham Gefter was a “national-Zionist.” His partner in business and also in the Zionist activity was Mendel Massis, who was active in Beltz since before WWI.

In 1921, at the first conference of Keren Hayesod, several delegates from Beltz participated. Yakov mentions the names Fredkin, Rafalevski, Tyomkin, Yachinson, Skavirski.

During the twenties (of the 20th Cent.) Beltz became an attraction point for Zionist leaders, in particular considering the economic situation of the Beltz Jews, who were an important source of the Zionst funds' income. The most important leaders who came to the town were Weizman and Sokolov, but there were others as well.

Yakov remembers the special money-raising campaign of Keren Hayesod. It was a one-time campaign. Every Jew promised a tithe – a tenth of his earnings; the women donated jewelry. He remembers his sister giving a fiery speech at the theater after which the women began to take off their jewels and donate them to Keren Hayesod.

The high-school students were accustomed, from an early age, to participate in the public affairs that were connected with Zionism and Jewish holidays, or other social affairs. The founding day of the Hebrew school, after one year, was marked by a public festivity in the municipal theatre; Yakov was in the 5th grade and his beautiful performance and speech in perfect Hebrew made him a sought-for speaker at such occasions. He was asked to speak in the name of the students, and he now remembers that he spoke with enthusiasm but didn't know how to finish, but then he remembered one of the poems by the poet Tchernichovski about the Jewish Kadish prayer and he finally concluded his speech with a line from Tchernichovski's poem “Od Shimshenu Ya'al” [Our sun shall yet rise].

He also remembers Jabotinski's visit in Beltz in 1925. He was a young boy of 15-16 and was appointed as attendant in the Hall. While the visitor was giving his exciting speech, two women in the public began to talk, annoying the speaker. Jabotinski interrupted his speech and asked the women, in his perfect Russian and with his known sarcasm, to stop – and continued his speech.

On his own Zionist activity in Beltz, Yakov mentions that he was an active member of Maccabi, the Zionist Sports

[Page 151]

Organization. He remembers the “Pyramids” during the Maccabi sports performances for the Beltz Jewish public.

Yakov does not tell much about his father Avraham's public activity. In addition to being the active head of the Hebrew High-School Committee – which was the main interest in his life – his father was for some time the chairman of the Jewish Community Committee in Beltz. The Zionist activity was conducted at the time by his good friend Mendel Massis.

There were no conflicts in the Jewish Community in Beltz, but there were some differences of opinion. There were always hot discussions between Gefter and Pinchas Levtov, an active Zionist personality, who owned a Hebrew Publishing House in Beltz. They made peace during a very unpleasant situation. It was at the funeral of the great teacher Reidel, one of the first high-school teachers and author of several schoolbooks in Hebrew. As R'Avraham Gefter eulogized the departed, Levtov approached him and took his hand. This was symbolic, showing how strong the Hebrew movement and its spirit were in the eyes of the public figures of the Beltz Jews. The differences of opinion were not personal; it was a well-meaning controversy [lit. “a controversy for the sake of Heaven”].

The Beltz Jews were simple folk, but practical. They created things: the exemplary Jewish and Zionist education in Beltz was their achievement. If their children could not go to the government school – they established their own private Hebrew school. And if there were no books – “we will make them” – they said in Yiddish, and found the teachers who could write schoolbooks in Hebrew, not only for the Hebrew subjects but for general subjects as well: the Levtov Company published them and they served the “Tarbut” schools in Bessarabia for many years. And if necessary, they translated books from other languages.

Of the first high-school teachers, Yakov mentions with admiration the teachers Kortchavnik and Bord.

Of the other Beltz community leaders, Yakov mentions only R'Shmuel Lipson, who was responsible for the spiritual life in town. He was a great philanthropist and in 1910 he even opened a Yeshiva. However, the Yeshiva functioned only two years, showing that the Beltz Jews were not attracted to the Haredi (ultra-orthodox) education; they preferred general Hebrew education, in a secular spirit. In his old days, R'Shmuel made Aliya to Eretz Israel, bought a house in Jerusalem, was active in the “House for the Aged” and donated money to synagogues and learning houses. He was buried in the Mount of Olives cemetery.

Yakov had pleasant memories of the Beltz cantors. His father loved good Cantor music. He remembers the cantors who began their career in Beltz and later became renowned in the Jewish world, in particular in America: Nisi Belzer, Efraim Shlyapak, Froike (Efraim) Hazan, a refugee from Russia. Yakov remembers the words of his father as he came home, one Shabat, from the “Great Synagogue” [Di Groise Sheel], excited by the prayers of the cantor. He was so elated, that he compared their singing with the voices of the Levites in the Temple in Jerusalem.

After graduating from High School, Yakov went to France with the purpose to study Law in Grenoble. But he was not accepted at the University, so he studied Commerce and Economics. He lived in France from 1928 to 1931. He fell in love with a girl, a student from Lodz. After he graduated – Engineer in Economics and MA in Economics and Commerce – he went to Poland to his wife's family. Her father was in the textile business, as were the majority of the Lodz Jews. Three and a half years he worked in his father-in-law's factory. By the way: he knew personally Oskar Kahn, the hero of the novel by I. Singer “The Ashkenazi Brothers”, which depicts the development of the textile industry in Lodz by the Jews. Oskar Kahn was killed by the factory workers. His son made Aliya to Eretz Israel, became a nationalist and dreamed of establishing a textile industry of an international level.

In 1931 Yakov came to Eretz Israel, with the capitalist Aliya, and established a weaving plant in Mizrahi Street, on the border between Tel-Aviv and Jaffa.

by Prof. Elkana Margalit

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| Professor Elkana Margalit – historian |

I was born and grew up in the streets of the poor. There I learned to respect and even admire the greatness and even the justification of poverty – but not any poverty. The Yiddish writer Shalom Aleichem has already described the various kinds of poverty. There is poverty that debases its “masters” and breaks their spirit, and there is poverty that honors its master. There are poor people who do not become degenerated by their poverty; on the contrary – they carry it with humor and even with a bit of pride – sort of a culture of poverty or poverty as a cultural experience. Many of those who rebelled against their destiny and their society came from these Streets of Poverty – rebelled out of love and longing; left but did not abandon; wandered away but did not forget the nest of their youth, because the special nature of that culture of poverty has become etched in their character: they were avidly modest and enthusiastic believers in seeking new ways. From these streets came many who activated, or were drawn into what can be called “the Jewish–Zionist revolution” – actually their own revolution.

Some of them founded the youth movements and the youth associations and flowed into them – the Hehalutz and the Zionist and non–Zionist parties. From the Poverty Streets came those who conducted fiery discussions, who desired to change the world, the “geniuses” of the town, all possessing a special imagination. They did not forget this special culture even when they left it. This was also the source of the Jewish “folksiness,” caring and charming and large as the world: the ideology and world–view of the youngsters grew from its roots. All of them were driven by the inner voice, the inner command, the needs and the dreams, and thus enlisted in the activity of paving a way to a better future. They left the towns of their birth, their parents, their families and their friends and wandered all over.

In front of my eyes I see the inhabitants of the Street: My rabbi – the melamed Hirsh Tzidnever – very, very poor; apart from the tables and benches in the cheder–room there was no chair in the house and his wife was dealing in firewood in order to help with the sustenance of the family; he was a great and wonderful learner – one of the many who became lost in the Jewish hardships. He was a skinny and weak Jew who didn't touch a fly and didn't hurt anybody – but on Simchat Tora he turned into another man: he drank wine and danced in the synagogue with the Epicoros [heretic] Godelman, one of the rich men in town – at least that is how I remember him. During the dance they exchanged their hats and Godelman called him “Grishka Cossack” – you should have seen this “Cossack”. Hirsh Tzidnever's son became later the leader and manager of the Gordonia movement. I think he did not reach Eretz Israel. And there was Leibush “Gaznik” – a big and muscular Jew who traded in petrol for lighting – poor but happy. When he was in a good mood he used to play on a comb. His daughter studied pharmaceutics, in great poverty.

And there was my own father z”l, a “modern” melamed in a “modern cheder” [heder metukan] – teaching in Hebrew. He was a devoted Zionist, a Jewish–Russian maskil [“enlightened”]. He would go from house to house to empty the Keren Kayemet [JNF] “blue box” – as a volunteer, of course.

[Page 153]

Together with Yasha Gefter he founded a Zionist youth association. He loved books and was enthusiastic about the Hebrew language, and read everything – even the “Communist Manifesto” which he found among my things after I joined Gordonia at the age of 15 (as a child I was for some time a member of Hashomer Hatza'ir). But when I went to the Hebrew High–School Tarbut I still wore my Tzitzit [“the fringed garment”] and I remember that the girls made fun of me.

And there was a figure that cannot be forgotten: “Dobe the milk woman” – an old hunchback woman, who lived in a cellar – earned her livelihood by selling milk to the Jews and supported two orphans, a boy and a girl, who had lost both their parents. The girl, Sara Bershak was my classmate at the high–school – she was beautiful and was loved by all boys. After going through hell during WWII she came to Eretz Israel.

The Jewish high–school “Tarbut” was a spiritual center for the young people. The boys and girls joined the youth associations and the Zionist and communist associations. All the teachers were fine teachers. I shall mention in particular the teacher Gleibman, teacher of mathematics, a pleasant man with a sense of humor; I remember, when I went to say farewell to him he was reading Critique of Pure Reason by Kant – a typical Jewish literate, a modest and polite man. Beltz was a relatively small town – with some commerce, craftsmanship and industry, in the extent of those days. The Beltz Jews, as I remember, did not excel in Tora or in secular learning; they did not establish famous Tora institutions, or famous Hassidic Rebbes and “courts,” or produce a famous “intelligentsia,” although Beltz did have poets and writers. But the Beltz Jews were warm, good–hearted – as was the entire Bessarabia Jewry – and more important, they were optimistic and full of vitality, initiative, activity and capability of survival – in short a deep–rooted Jewish population with Jewishness implanted in their being. If someone asked what was the meaning of being a Jew he would arise a smile – at least in those who were called “Amcha” (“the folk”) who were the majority. Everything was Jewish: the language was still Yiddish and most of the youngsters knew Hebrew. Until the mid–thirties (when I made Aliya) the impression of the Russian culture and language was still strong. I remember that in my parents' home there was a considerable library of Russian classics, as well as philosophy and political literature – original and translations.

Until WWI Bessarabia was under Russian rule, and part of the Bessarabia Jews came from the Ukraine. In the town named Ackerman the Russian language was used, but the Jews learned Hebrew and there was also a Hebrew high–school. The separation from the Gentile environment due to active, and even violent anti–Semitism, the Hebrew and Yiddish schools, the tradition – not necessarily in its radical religious form – all these crystallized into a natural “Jewish feeling,” self–evident, without the necessity to explain or rationalize. All could be expressed by one word: the charm of the “folksy Jewishness” – this was the secret of the strength and influence of the Beltz Jews – and of the entire Bessarabia Jewry. It was a special kind of culture; out of its strength a relatively small Jewish community succeeded to establish Jewish cultural and educational institutions, a Jewish high–school, Hebrew and Yiddish libraries, political parties and youth organizations.

Within this environment, the national and Zionist dream was impersonalized as well. On Lag Ba'omer the young people, and many of the adults, singing songs and carrying national flags marched to the Hechalutz training farm Massada, several kilometers out of town.

This Jewish folksiness was the culture of the Shtetl, even when it grew and became a town. It was the identification with the Jewish existence. These were “all year Jews” [ordinary Jews] who suffer, dream, aspire and at the same time are very “worldly,” strong and fighting for their Jewish and private existence with all their might. This was where we have all grown from, and this was the source of our inner command.

by Chanoch Goldstein

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| Goldstein Chanoch (Nona) |

I was born in Beltz in 1910. The first feelings of contact with the external world rise now from hidden parts of my brain: I am hearing the iron sound of the peasants' carriage wheels, and the sound of the horses' hoofs on the pavement; the blows of the hammers and the noise of the saws cutting the wood. The street was called the “Carpenters Street.” It was one of the Jewish streets (Petrogradski), which ran from the Saint Nicholas Church down the grade: a group of crowded houses without passages between them; dark rooms.

On Sundays, the noise and tumult were great. The peasants who came to buy things argued with the store owners and the craftsmen about the prices, shouted, tried to convince the others, made agreements; at times, the young sellers tried to cheat the buyers and aroused anger and hate.

On Shabat, the street was quiet. Jews were sitting in front of their houses, eating sunflower seeds and gossiping. If a passing Jew violated the Shabat law by smoking or riding a bicycle, they would scold him.

The water–carrier brought drinking water; every day he would pass through the lower part of town, on his wagon pulled by two mighty horses and provided water for the Jews. The street bored me. I preferred reading the books by Emil Zola. Since the end of the 19th century, a Drama Club was active in town and performed the Goldfaden plays: Bar Kochva, Shulamit, The binding of Yitzhak and others. Members of the drama club were: Shamay Feldman, Yoel Bronzon, Rosenthal, his mother and her brother Shabtay, Moshe and Yosef Lerner. Shamay Feldman has founded the theater and managed it for many years. The theater played an important role in the cultural life of our town. I was four when my sister, aged 15, was the prima donna of the musical ensemble that settled in town (the Miloslavski Family) and performed musicals, for example “Little Red Riding Hood.”

At the height of WWI, our neighbors, the men, would get together, drink tea, eat little in order to lose weight and become unfit for the front, and argue: who would win the war? These were days of poverty and fear. Bessarabia was an abandoned region and history reached us late; the 1917 revolution was a surprise for us. The spring was a time full of hope. Together with my age group (7–9) we organized a demonstration with red paper flags, with proclamations “Long Live Kranski” etc. and songs of the Revolution. And suddenly, bad news in town, hints: Jews began talking about pogroms… Our neighbor's cellar was full of huge barrels of wine. One day I peeked down through the second floor window and saw soldiers bursting into the cellar, taking out some of the barrels and stabbing them with their rifles. Wine began to pour between the road and the sidewalk; the soldiers went down on their knees and drank the wine with their hands. Then they began plundering, joined by the crowds who lived on the outskirts of town. Next day – the market day – the plunderers came to the market to sell their spoils to the peasants.

[Page 155]

The Jews attacked the plunderers, took from them the stolen things and threw them on the porch of the Krek house (Chaim Krek lives today in Holon), and the same day they were returned to their rightful owners… A little later, the Romanians came, and behaved toward the population like conquerors. For a small “sin” one received “5 blows” A greater sin was estimated as worthy of “35 blows.” Drunkenness, blackmail and bribery were the rule. “Tuica” took the place of “Vodka.” Very fast we learned the Romanian National Anthem…

During the first half of the twenties, a new young star appeared in our town – Grisha Starosty. He had a wonderful organizing talent. He founded the scouts' organization (Hashomer Hatza'ir), whose members included: Shulia Masis (the contractor Shalom Masis from Tel Aviv), Fredman, Steinberg, Polia Guttman, Yatom, Binder, Herzl Goldstein (my brother). This organization was full of idealism. The discussions were held in Russian, but they included a great amount of love for Zion. I shall now devote some of my lines to the life of one person of that group, my brother Herzl z”l. He was born in 1905 and was named after Dr. Herzl who had just died. He studied with the teacher Dubinovski. After several years, it became clear that he had become an expert in the study of Hebrew and of the Bible. Knowledgeable people were of the opinion that he was a genius. He was the only student about whom the very strict teacher Lepanski said that he knew history. His notebooks were full of poetry that he had written. He excelled in arts as well – in music and particularly in painting. He was 14 when his poems were published in the United States. In the summer of 1921, the representative of the Jewish Agency, Rabelski, came suddenly to Beltz to make a speech, and Herzl Goldstein was given the task to reply to his speech. In front of the public he improvised a speech, and when he finished, Rabelski approached him, embraced him and kissed him. The public was stunned. The next day he was taken ill and two weeks later he died. May his memory be blessed. About a month before he died he wrote a story about the death of a person by the name of Hirsh Goldin. His heart had told him about his own approaching death. The same summer, the loved young man Binder drowned in the river, and the fine young man Guttman Filia z”l took his own life.

….During the summer, the Maccabi and the Hashomer Hatza'ir organizations held their meetings in the large courtyard of the Big Talmud Tora. The first Maccabi instructors were Gurewitz and Feldman. After them came Drachman and Madzhovski. The excelling members were Marenfeld, Munia Masis, Nania Leiderman, Misha Tennenboim. As to Hashomer Hatza'ir – I shall mention that I remember the leader of the organization Shuster, Israel Grogerman, the young ladies Fredman, Kramerman. Levy Greenblatt was the head of my group. Later I joined the Sela group. We had also the Beivar group, which was an excellent group. It included, among others, Finkelstein and Loibman. Some of the youngsters excelled in playing chess – they played with eyes closed, while walking in the street. We should remember also Avraham Greenblatt (Levy's brother), Yatom, Fredmann and others. At that time, “The Youth Committee” was also active in town, managed by Flum, who was full of life and initiative, and had a vivid imagination. He invited actors to perform for our public, and was involved in all cultural activities. The Youth Committee had a library with books in Yiddish and Hebrew; discussions were held between Right and Left and between Zionists and Bundists. The Krimski Family was one of the active families; they organized a chess club. I remember another Zionist group – Hasho'ef – which was active only a short time. Its founder Yakov passed away.

…. I should now tell a few things about my classmates. At the beginning of the year, as I was in second grade, a new boy came, dark hair and a face of a girl. He excelled in the study of Hebrew and the Bible [Tanach]. His name was Chaim Hochman – now he is a writer and lives in Bat Yam.

A grandson of a Sofer Sta”m [scribe] settled with his family in Beltz – they came from a town on the shore of the Dniester River. He was a shy boy, almost didn't participate in the “events” of our class. He was very talented and had a wonderful memory and a sense of responsibility, and had a great fear of defeat. Starting from 5th grade he participated in discussions about Hebrew and Yiddish literature, in the framework of the Youth Committee.

Avraham Greenblatt (Levy's brother) was a mathematician and played chess. In matters of morals – he was far from his brother.

When I was in 4th grade, several pupils from small towns in the neighborhood of Beltz joined: from Ungheni, Britcheva, Capresti. Later they left. Bonder from Britcheva lives now in Israel.

Zak from Britcheva – the genius – is a lecturer at a university in Paris. He wrote a book about Spinoza.

Several of the pupils joined the “Hashomer Hatza'ir;” the teachers were not happy about the liberalism of these pupils, and finally they left. Zionst education was not very manifest in school.

[Page 156]

I was a member of the SELA group. My classmates Feibke Feldman and Daniel Goberman are now members of the Kibbutz Sha'ar Ha'amakim.

My classmate Lazer Dubinovski was a really rare case. I knew him since I was 3 years old. His father, who was a teacher, came with his little son to our house to discuss my brother, who was his pupil. As he was talking with my father, Lazer and I were sitting under the table. Suddenly Lazer took a piece of paper and a pencil and made a few lines – and to my great surprise a wild horse appeared on the paper! Years later we met in the same classroom. When we were in grade 4 or 5 he committed a great moral offence and was expelled from school – a very unusual case. Actually this was his luck. He began doing sculptures, and since he had a sense if initiative and was daring, he opened a school of sculpture. Several years later he began working as a teacher of Art at the same school from which he had been expelled years ago. During the War and after it he became a well–known sculptor, and was also a member of the central committee of the communist party in Moldavia. In his CV there was no mention of the fact that he had lived in Beltz. His father, a teacher and a devoted Zionist, who was his good friend all his life, he buried in the Armenian Cemetery. Yet he was a good friend and helped the Jews. May his memory be blessed! In his later years he drank much and played cards.

In high–school we celebrated Hanuka and Purim by a great party, a ball. The money that we collected was used to pay tuition for the needy pupils. We had an orchestra of wind instruments – the members were students and the conductor was one of the teachers, a specialist in military orchestra. Later, a graduate of the school, Yitzhak Feldman (brother of Feibke Feldman from Sha'ar Ha'amakim, lives today in Kiryat Tiv'on) was appointed conductor of the orchestra. At the festive parties, they would perform historical plays and recite poems. Several choirs would perform songs in Romanian and in Hebrew. The conductors of the Purim and Hanuka songs were the teachers Reizl and Bord, of the Romanian songs – the music teacher Tatashencu. The public was: the students and their parents. After the formal performance, they danced all night, at the music of the orchestra. A rich buffet served the public. On Purim there was also a masked ball with a lottery. But the most important holiday in the life of the school was La”g Ba'omer.

In general, our town was like a Jewish state. Industry, commerce, shops, craftsmen, restaurants – everything was Jewish. The periphery was Christian: Ukrainians, Armenians, and some Moldavians. They were peasants, porters, wood–cutters and water–carriers. On La”g Ba'omer, the schools and the Zionist movements marched out of town with flags and orchestras: the Jewish high–school, the Talmud–Tora, Hashomer Hatza'ir, BEITAR, Dror, Gordonia, Maccabi. Accompanied by hundreds of Jews, all went to the Biliceni farm, Massada. Almost no Jewish person remained in town. The “pioneers“ in the farm welcomed the guests, danced and held speeches.

…. A little about the communist movement in our town, from what I know and remember: In the early twenties, I knew several assimilated young men and women who were members of the movement: Refael Yampolski, Chaika and Moshe Kushnir (brother and sister), Leibush Rosenberg, Malka Greenberg and others. Later, Refael Yampolski disappeared. In 1932, the nationalistic Farmers Party, haters of communism, won the elections. Provocateurs organized groups of sympathizers – most of them young Jews aged 14 or 15 – turned them into communists and then handed them over to the rulers. They were tortured and turned into invalids.

Another active group, headed by Munia Masis included the girls: Fachter, Tania Boyzhor, Chana Kelser and Rosia Reidel, the daughter of Yakov Reidel. Later she became one of the important figures in the Romanian communist party. The most prominent figure in Romanian communism was Lyonia Eugenstein, later Lyonty Răutu – the theoretician of the Romanian Communist Party. He was a graduate of the Hebrew High–School. His wife was Yakov Reidel's eldest daughter. The head of the Secret Police was Iza Abramski, the known detective Fritz.

… Beltz was situated on the main road between Yassy and Tchernowitz – both industrial and commercial cities, but different from one another. This greatly advanced our town in the area of commerce and industry. Factories, flour mills, shops, restaurants, the grains stock–exchange – belonged to Jews. The town was active from early in the morning until late at night. In the summer, the public park was crowded. Two orchestras played for the guests in the park and in the restaurants.

[Page 157]

The Popov and Poilisher restaurants were always full and the violin, accompanied by the piano, was always playing. The coffee–houses Frangois, Paris and others placed chairs and tables on the sidewalk. Those who returned late from the Cinema or Theater went to the “Deli” restaurant to taste the best ice–cream in town.

The theater played a very important role in the cultural life of the town. In the early twenties, almost every day a Yiddish play was performed. Not all groups (like Campus and Siegler) excelled artistically, but they helped the soul. In time, the famous Vilner Troupe came to our town, with the actors Baratov, Latison, Clara Yung and others and the world–famous actor Ronitz, the singer Wertinski, the Zherov choir, the violinist and composer Enescu. The students and the youngsters would be accepted into the Hall according to a list and paid half the price for a ticket. They also organized lectures and literary discussions. Several libraries were active, among them the library that was situated in the building of the Jewish Bank, with Russian books (Erenburg was famous at the time), the library that belonged to the “Youth Committee,” the library of the “Cultural League,” the high–school library and more. There was also the private library of the typesetter Yitzhak Sternberg, who loved literature. Discussions on literary subjects were held in all these places. The German literature was very appreciated at that time, since its level was high. The youngsters would meet in several places, among them the workshop of the tailor Surkin (the brother of Zeilig Berditchever). The youth was inclined to follow the leftist parties – the following names are worth mentioning: Kazhber (Weinstein) Rivkin, Cheretz, Surkin, Liatker, Berditchever, Ruchama Goldstein (my sister). These were the years 1930–1934.

Religious life? There was almost none. The doors of the Batei–Midrash were closed, and opened only on the eve of the “Days of Awe” (New–Year and Yom Kippur) and the three main Holidays. There was only one synagogue. The Batei–Midrash were: The Big Bet Midrash, Cheretz, Sadigora, Yehuda–Leib, the Attendants' Bet Midrash, the Cobblers' Bet Midrash, Sha'arei Zion, and others. During the Kol Nidrei prayer on Yom Kippur, Christians were also coming to the Big Bet Midrash. I remember the cantors: Fossman, Froike the Cantor, Yakov Riman (who was not religious) and Kaiserman.

… I shall mention also some of the private schools, called by the names of their principals: Dukhovni, Dubinovski, Wergaft, Doktor, Geisser. Private teachers were: Fischler, Margalit (father of Professor Elkana Margalit of Tel–Aviv University).

The balls that were organized in town were all charity affairs. Apart from the high–school festivities, there were once a year the following parties: the Talmud Tora, the Bikur–Holim [helping the needy sick people – lit. “visiting the sick”] and the Armenians. The program included plays, solo appearances, speeches, dances, orchestras. The festivities caused much elation.

Until 1937, the Beltz Jews have known no fear. During the second half of the thirties, when the Cuza people went out of hiding, the Jews did not pay attention to them. Mostly they were afraid of the Jews.

On the eve of Simchat Tora, a demonstration of farmers marched through the streets, and almost at the same time the Jews accompanied their Rabbi to the synagogue… But in 1937, when the Cuza–Goga government came to power, life in our town began to change. Bad news spread in town, and they soon became a reality. I shall mention a few cases:

The devoted communist, who had only one eye, was released from prison by the secret police, without trial, so that his friends would think that he was a provocateur. They really began to keep away from him. He declared: “If I am a traitor, then let the Russian party, across the Dniester, judge me.” He crossed the Dniester and was sentenced to death. In general, all communists who were unsuccessful in their work and were sought by the police crossed the Dniester. They were immediately arrested and exiled to the Nord, and several years later to the far North. Malka Greenberg, whom I mentioned earlier, crossed the border and was exiled to a concentration camp in the North. Later they brought criminals and forced her to satisfy their sexual needs. She told that to her friend later, when she was rehabilitated.

… In 1940 and 1949, the Soviets organized two deportations to Siberia. They said that the local communists (the Jews) whispered in the ears of the authorities the names of those who should be deported, since the Soviets did not know the inhabitants of the town. Some of the youngsters, formerly enthusiastic Zionists, turned suddenly into communists and helped with those operations.

[Page 158]

It is probable that in the years of the pogroms in Ukraine, the Western Powers instructed the Romanians to allow refugees to cross the Dniester to Bessarabia. The border guards took advantage of the situation and, with the help of Jewish informers, were bribed in exchange of enabling the crossing. Some of the bribers were drowned in the river (the reason is not known). It was said that an important figure in our town was involved in this operation – I shall not divulge his name here. The famous trial – the lieutenant Morarescu trial – was connected with this operation.

by Misha Fuchs

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

| Misha Fuchs |

My home

There are differences of opinion on the subject “memories” in particular, there is no agreement as to the time of the first memory of a person.

Some say that the age of 4 or 5 in the life of a child is the time when events or life-experiences become fixed in the memory cells of the brain and accumulate there – others think that only later the memories are clear and are preserved in detail.

I must state that I belong to the second group, but events that happened in my thirties and my fifties took me back to the twenties of the 20th century, which were my happy childhood-years, in a well-to-do family, big house, several spacious rooms – my home. By the end of our War of Independence, I was among the first settlers in the renewed city of Akko and I worked in the field of education, culture and tourism. I was one of the founders of the Municipal Museum.

During the first half of the fifties, the artist Avshalom Ukshy, also living in Akko, asked me to assist him in the exhibition of his paintings in the special museum, located in the magnificent building of the former Turkish Bath, Hamam-el- Pasha, in the Old City.

The painter asked his teacher Yosef Zaritzki, the king of the Israeli artists, to come to Akko and help him hang the paintings. Zaritzki came to Akko and the work was done under his instruction and supervision, and when it was finished, in the small hours of the night, Ukshi asked us to come to his home for tea – we sat relaxed and sipped tea and talked. Among others, Zaritzki was interested in the origin of my name: “Misha?” he asked “Are you from Russia? This is a Russian name.” I replied that I was not from Russia. My father was born in the Ukraine, and I was born in Beltz. “Beltz?” the painter jumped up – “you will now have to listen to the story of my own 'exodus from Egypt' even if we sit here all night.”

“My story is the story of a refugee from pogroms and riots, which followed the Bolshevik revolution. The Petliura and Denikin bands forced most of the Jews to flee. We looked for all kinds of strange ways to escape the horror. I chose the illegal road. I and a group of refugees waited for mid-winter, for the days and nights of cold which would freeze the waters of the River Dniester, the border between Russia and Romania. On a dark and cold night, we went out to “steal the border” and we did succeed. On our way to the soil of Bessarabia we were welcomed by a well-organized group of Jews, who performed their work professionally. Their main job was

[Page 160]

|

|

|||

| Welvel and Bracha Fuchs, parents of Fania, Sioma, Ada and Misha | ||||

to take us the same night as far from the border as possible. We left on a wagon in the direction South-West, accompanied by wishes of success: Go in health… We wish you success…”

We reached Beltz and the supervisor took us to the Jewish families who had agreed beforehand to accept refugees.

Tired, hungry and frozen, I was taken into a warm and spacious house, where I found shelter from the cruel bands and the troubles of the road. The gracious welcome warmed my heart. I ate, was given warm clothing and new shoes, but more than these, the encouragement and support that I received in this house gave me a new taste of my life and a strong will to go on. The house and the owners Bracha and Welvel Fuchs are kept alive in my memory to this day and will be remembered to my last day.”

Thus ended the story of the artist, and I froze. I could not open my mouth. The persons present in the room observed my excitement and could not understand it; I was choked by tears, but finally I managed to whisper: “I am Misha, the son of Welvel and Bracha Fuchs and all that has happened in my home.”

Much later, some thirty years after my meeting with the artist Zaritzki, my wife Tzipora and I made a trip “coast-to-coast” in the United States of America. In New-York, we did as all tourists do – we visited the famous centers, the museums, Broadway and also “the Lady with the Torch” – the Statue of Liberty. As we were in Manhattan, we remembered that one of our Beltz friends, Yose'le Mazor, was in the US on a national mission and his office was situated in the heart of Manhattan. We went to the Empire State Building to meet him in his office and shake his hand.

Yose'le welcomed us and was glad to meet us. We sat and had tea, and our common memories from Beltz began to come up. Yose'le remembered an experience that he had while he was a little boy and began to describe it; I closed my eyes and I saw the picture in detail: “It was a winter day and a storm was raging outside. Snowflakes hit my face and the cold stung and froze my ears. I stood, holding the hand of my father, one of a long line of Beltz Jews, near the house of Misha's parents. The purpose was to reach the door, go in and be seen by the

[Page 161]

Rabbi, who stayed in their spacious and warm house, to shake his hand and receive his blessing.

The people asked for advice, usually with personal problems. The rabbi would listen, think, and say a few words of encouragement and advice and they would part. On their way out they would pass through the “treasurer” and leave a donation for the Rabbi's Court.”

Since our house was big, it served as lodging, alternately, for the Rabbi of Sadigora and the Rabbi of Shtefanesht [ªtefãneºti]. The “impresario” of the rabbi would come some time before the visit, check the “ground,” decide upon the length of the visit and take care of advertising and public relations – usually “the rabbi would stay about two weeks…” etc.

My parents would give the rabbi several rooms, a separate kitchen and service rooms, as well as a separate entrance through the porch in the yard.

His “entourage” was: a cook who brought his own dishes, an attendant, Gabays [managers], a treasurer and a spokesman. They would arrive several days before the rabbi, and prepare the event in detail; in most cases the visit was very successful. On the day the Rabbi was supposed to arrive, a long line would already wait for him – every one wanting “to be first…”

My parents supplied all needs of the guests, especially heating in the winter, and filled any request of the Rabbi. I should mention that my parents did not lead a strictly religious life. I would join my father when he went to the synagogue on Holidays and sometimes on Saturdays. It would be correct to describe our home as traditional, adapted to the circumstances.

This was how Yose'le remembered our home from the time he visited us as a child, when he came to receive the blessing of the Rabbi – and this was how he took me back to the days of my childhood.

Yose'le's story touched the heart of my wife Tzipora, as she was the granddaughter of a Rabbi and proud of her roots. Her grandfather, who had made Aliya to the Holy Land at the end of the 19th century and is buried in the Mount of Olives Cemetery, served for many years as the rabbi of the Community. Tzipora asked: “Misha, why did you never tell us?”

* *

*

A foolish act

We used to spend our summer vacations at the shore of the salty lake [Liman] near the mouth of the Dniester River as it flowed into the Black Sea, on a narrow strip of white sand that extended between the Lake and the Sea. On that strip of land was a small summer resort called Budachi. But we did not always go to the sea – on some of the vacations we went to resort places in the Carpathian Mountains: Vatra-Dornei, Câmpu-Lung and others. The story I am about to tell happened either before or after we went to the Datcha – in any case, this is a strange story.

I took an active part in the cultural life of the children of my age, showed initiative and organized sports and recreations. I planned trips and told jokes, and even dared take part in adventures.

One hot summer day, a group of children gathered near our house and we started walking toward Kishinovski Street, on the way to the bridge over the Rãu?el (a small branch of the Rãut). The bridge was called “The Kishinovski Bridge.” I don't remember whether that “trip” had a specified purpose – unless it was to collect leeches which we kept in special bottles, or perhaps only to wet our feet in the water or to breathe the fresh air.

We walked joyfully and happily and children, who lived on the streets we passed, joined us as we went.

We arrived at the tavern owned by the parents of our friend Riva Pozis, to ask her to join us. We waited, a noisy, almost wild group. To this day I don't understand what drove me to get interested in the garland of hot peppers that hung at the window – strung on a wire to dry during the summer – perhaps the beautiful color? Perhaps just curiosity to touch and see how dry they were and how long we would have to wait until they could be chopped and turned into spice?! I touched with my hands the hot peppers and my hands were filled with the sharp and hot powder. Riva joined us and we left.

[Page 162]

It was a very hot day. We sweated, and without thinking I passed my hands over my face to wipe off the sweat and touched my eyes. I felt a very sharp pain and my cries reached Heaven. Passers-by who did not understand what was happening asked “Who is this child?” Soon two people called a wagon owner and took me home.

My parents, scared, called the doctor, but he was helpless and did not find a solution to this mystery. Our neighbor remembered the experienced feldsher, who sometimes knew how to solve problems better than a doctor and was much respected in town. Indeed, he immediately took control of the situation, after a short check-up and testimonies of the children, who came running to our house and said that they thought he has touched hot peppers.

The doctor opened his bag that contained various instruments and ordered to bring ice and milk. Where would one find ice in a hot summer-day? Not in the deep-freezer, of course. But there was a custom in Beltz, and probably in other places as well: during the winter, people used to cut big pieces of ice from the frozen river and store them in a special device called “lyodnik” which in Beltz was located in the “Rebele's courtyard” (this is what Rabbi Landman's yard was called).

I shall devote a few lines to describing this device: in the middle of the yard was a large pit with a spiral staircase leading inside, which served to keep the ice and preserve it solid. During the winter, blocks of ice of various sizes were placed on shelves, separated by layers of straw for insulation and for avoiding the formation of large blocks. Around the pit they built walls of reeds and covered it with a slanted roof, also made of reeds. This way it was possible to use the ice during the summer in medicine and industry, for example the ice-cream industry. Right away they sent someone to bring ice, the doctor put some ice in a dish of milk that they had brought, dipped in it a “compress” [bandage] and put it over my eyes. When the compress lost its humidity and became hot, it was changed.

And the miracle happened: my eyes opened widely and the pain disappeared. Indeed, I had done a foolish thing.

Education and…a little folklore

My parents invited for us private teachers of Hebrew and Russian, when we were at kindergarten age and school age, first my sisters and my big brother and later I, the youngest.

The atmosphere in our home was Jewish, Hebrew and Zionist, and it influenced the children. I remember all this as through a fog, but it is an integral part of my childhood memories. Mr. Wergaft would come to our house to give private lessons in Hebrew – Modern Hebrew, in addition to what I learned in the cheder.

Many years later, the sons of our teacher Wergaft made Aliya, Hebraized their name to Amit and settled in a kibbutz. When the grandfather came to the kibbutz he had no problem communicating with the little children in Modern Hebrew – only a few words he pronounced the way they were pronounced in the Diaspora, but he learned fast. Russian I learned mainly from my aunt Ethel, wife of my uncle Shaye Fuchs, my father's younger brother. He was an interesting person – an intellectual, a strange mixture of a leftist and an industrialist.

When I said leftist I meant a person belonging to the Cultural League, an idealist, knew Hebrew, a man of the book, smart and diligent and more than everything – cynical. He wouldn't mind if asked whether he was a communist or a capitalist; but the peak of cynicism was when he was welcome with “Good morning Shaye” and he replied “Nu, nu!” [well, well!].

[Page 163]

There was no doubt that I would continue my studies in the high-school where my sisters and my brother Sioma have learned – many are those who remember the admirable institution called “The Hebrew High-School of Beltz” – with its teachers, students, uniform, flag, orchestra, parades, trips and more. I have no doubt that in the pages of this book we can find many other details, experienced as an important part of the lives of those who studied between its walls.

I would like to mention an experience connected with preparing the first uniform for the pupil who was about to study there:My mother went to the store of our neighbor Antchel Grobokoptel, presented the “candidate” and asked for a piece of material “so it would suffice”…

At home, a discussion followed, who will receive the fabric to sew the uniform. The decision: Yankel the tailor! And why? … My grandfather, David Yakir, owned a few small houses at the edge of town, near Vodoketchka. In each of these housed lived a craftsman. They were not very punctual in paying the rent, so grandfather would always remind his children and grandchildren:If you have some clothing to do, or if you have some other work for a tailor, a cobbler, a carpenter, go there and give them work. They don't pay rent, at least they should produce some work.

Indeed, I went to Yankel the tailor with the fabric, the lining and the shining buttons, to “take measures” and fix the date for the first fitting. I don't remember why I chose a Friday for this activity – but at 10 in the morning I was at Yankel's door with my package. He was sitting by the sewing machine, sewing and singing. He raised his head and looked at me through his glasses, on the tip of his nose. His look was enough, he didn't need words.

I understood the hint, and I whispered: “I understand, this is not a good time, I will return some other time.” But Yankel, with his charisma and strong voice said/ordered: Wait, young man, come in and sit down – I couldn't say no to this man, and I don't know whether anybody ever said no to this tailor.

“You see” – he said – “this suit, which is almost finished, I promised Gospodin Gendelman that he will have it today. These trousers I have to iron and prepare them for Mr. Glotzki. This vest, only the buttons are missing and in a few minutes they will come to take it.” All this he said while sitting bent over the machine; then he rose slowly, took the trousers, vest and suit, made them into a ball and threw it into the corner of the room; this energetic act apparently solved all his problems, and he said: ”Now I am going to the bathhouse!” I thought this was a very logical solution and I can go home. I tried to say something like Shabat Shalom and go.

But this was not what Yankel thought. “No, young man, you go with me to the bath” he said. Then he turned to his wife Rachel and said something that I didn't understand, and she appeared holding a bag full of towels, clean clothes, food and drink – vodka, I think – fresh bread, herring, onions and other vegetables.

R'Yankel took my hand and, sure of himself as usual, took me to the bathhouse. In my young years I have never seen a public bath from the inside, certainly not a Turkish bath (a steam bath). Like a prisoner in his hands, I reached the bathhouse and a low and wide door opened in front of us.

The entrance hall served also as a wardrobe and near the walls were arranged closets for changing, each closet had a door that opened and closed on metal hinges. Inside the closets, the clothes and bags were hung on nails stuck on the walls. R'Yankel's order to me “Get undressed!” was obeyed immediately, either because of my own curiosity, or because R'Yankel was a good educator – firm, but not pressing.

[Page 164]

The end of the story was that the event, which began in the “realm of the unknown” turned, step by step, into an unforgettable experience. In the dark part of the hall there was an opening in a thick wall, a heavy door closing on it. I could not open it by myself, of course, but R'Yankel the teacher gracefully helped me at all stages – come, he said, help me! and together we opened the door and found ourselves inside a room full of people. I couldn't see them because of the steam that filled the air. I almost couldn't breathe, but slowly I got used to the place, the “cloud” began to disperse and I saw Jews of all ages and shapes. Most of them were elderly, and the real shock I got when I saw the hanging limbs, all kinds of fractures and additions – the first time in my life that I saw such things.

The first few minutes that I was left alone, R'Yankel began a discussion with the public. He was well-known, he probably told them about the “person” he had brought with him, who was a “greenhorn” and very scared. But he will get used to all – in the hands of R'Yankel he will not remain a spoiled little boy.

When the tailor realized that I gotten used to the place, he took me to the first (lowest) row which was not very hot, for beginners – to me it felt very hot – and began massaging my back and hit it with the special instrument for this purpose: a brush made of young sprigs. I thought I was going to faint. I tried to move my hands in order to send him the message, and soon a wooden bucket with cold water was brought and the water was poured over me. This is what returned my soul to my body – and it meant that I already got used to the thing.

The compliment I received was formulated by R'Yankel and was spoken loudly by the crowd of his friends:“Since this was the first time that you, young man, are visiting here, we must say that you have passed the test.”

I remember every detail of this event. I admired R'Yankel, a folkloristic Bessarabian figure like thousands of the Jews of this region, who perished during the big Holocaust and were wiped out from the face of the earth. I would like to consider these lines as a memorial to the tens of thousands who were murdered and never had a Jewish burial.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bălţi, Moldova

Bălţi, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 Sep 2024 by LA