|

|

[Page 272]

By Dov Sadan

While still a child, before his capabilities and reputation became widely known, he had the nickname, The Genius from Zolkiew. His city was a City and Mother in Israel, and its memory was held in esteem in the chronology of our community. It has been generations since the spirit of Torah filled its spaces. It is sufficient for us to look a little bit in the book, The Sublime City. It is sufficient for us to briefly recollect the names of the Torah scholars in it, such as the author of Tevuot Schur, the parent and teacher to the perplexed of our time, with the author of Ateret Zvi. It is a city that became sublime and survived with a living tradition of learning and scholars. One had to be filled with an overflowing sharp-mind and fluency in order to earn the nickname, genius. In truth, little Benjamin had all of these virtues. His sharp mind created a quandary. His memory was a wonder. His ability to compare things brought on astonishment. It is right to say about him in passing, that he is, and will continue to be, a riddle.

He was born on the Street of Tailors. According to the Kabbalah, it was the blessing of a Tzaddik to raise a genius. His father, the impoverished tailor, R' Yehuda Hirsch, worked on the street in a small and rundown house. His son would say that his father was a patch worker, not a tailor, but rather one who patched things. The core of the father's income was from the Dominican monks in the city. He sewed their garments, and the monks paid mostly in the equivalent of money, sending him firewood from the monasteries, and the like. He worked speedily, but when sewing machines became more commonly available, he could not compete, and he ceased his manual work. He and his wife decided to raise geese. And it happened that they lost the little money that they earned in this way, and that the father assumed the obligation of several occupations had become a matter of jest. He and his wife worked at a difficult business, day and night. And it was said that his father did not refrain from forbidden work among the farmers in the surrounding villages. He went to them in order to repair and patch their clothing. But he had an intense love of Torah and its trappings within him. Even going back to his childhood, if he had a spare hour, he put down his needle and sat in the Rabbi's house. The Rabbi was the well-known Sage, R' Zvi Hirsch Khayot.

From the heights of a fallen house and filled with want, Benjamin would walk about in worn out and torn clothing. This was because his father, the tailor, didn't have the time to sew on a few patches on the clothing of his little son, who was renowned for his sharp mind and scholarship. He was a youth among others on the street. He was always hungry and thirsty, and would seize a slice of bread from a friend's hand, and run; that is how to describe his poor childhood. At the age of five, his father took him by the hand and led him to Heder. The next day they came before the Melamed and the father asked if there was a purpose to pay the tuition for teaching his jewel, his son. The Melamed answered: ‘What I dreamt last night and the night before will fall on your head. Here you have barely come into my rooms, and already you expect that he will know the entire Torah ‘on one foot.[2]’ Two weeks did not pass when the Melamed came running to the tailor to say: ‘take your son out of my class, because he has already upended my vessel and squeezed it to emptiness. It was not that the boy had any special speed, but he had a gift, because he taught himself. He is a ruffian who climbs trees and fences through most of the hours of the day, and in two weeks, he learned what it takes the remaining students several periods to learn.’ And the boy felt confined in the Heder of the Melamed, confined in his house, and confined in his city, and his heart was drawn to the enchantments of the large world.’

[Page 273]

His mother, Chana Mir'l who came from the family of one of the first musical bands in the city, Die Tzymbleress, which played at more gatherings than weddings, including army celebrations. She was the one who strongly and wholeheartedly believed in her son, which was not the case with his father, and she was overly committed to him. During the winter, residents on the side streets saw her carrying her son on her back, in the morning and evening, to and from the Heder of the Melamed. The boy's legs were wrapped and bound with worn rags since she did not have the wherewithal to buy him shoes. When her son grew up, even she understood that the walls of the city were too confining for him, and again, she allowed him to leave and attend a Yeshiva. He attended several Yeshivas, in Lvov, in Prszemsyl and even Hungary. A story about this mother touches the heart, for when she wanted to see her Benjamin, she walked for many days until she reached the city where he was studying. She entered the Yeshiva courtyard, called to her son, gave him a pear and said: Benjamin my son, eat, eat.

His mother tried to send him to Belz every year before the High Holy Days, but there was a large barrier. Even though his father was a tailor, he did not have proper clothing. One year, he had the good fortune to get his father to make a pair of good-looking trousers from leftover pieces of fabric, but the trousers did not end at his. And this is what happened. Hasidim traveled to Belz for the High Holy Days, and took him along. He asked to be presented to the R' Yehoshua'leh, to give him a greeting of peace. However all of his strategies to pull this off did not work. He said to the other youths, who were also pushed off like me, ‘Chevre,[3] this is a waste of time. Let us go bathe in the river.’ But as they took off their clothes and let the end of their toes go into the river water, suddenly a youth appeared like an arrow shot from a bow. His sidelocks spread out from hither and thither, and yet with all his soul, he shouted: Er Nemt[4]! He wanted to say that the Rebbe was now accepting greetings. So all the swimmers in the river came out to put on their clothing. But since he was anxious to come first, he jumped with both legs into one trouser leg, and began to run. It was only in the middle of running did he feel that both legs were in where they were, and the trouser leg split. But he did not stop his pace until he reached the Rebbe and gave him a greeting of peace, and received one in return.

It was not easy to earn the designation of a genius in Zolkiew. Not only because of the geniuses of the past, and not because of R' Yehuda Maimon, another genius in those days, but also because there were several groups of young men who manifested formidable learning skills. Three of these young men were exceptionally praised. One of them, R' Itzik'l Rubin was a relative of the Rebbe of Belz, who later on became a Dayan in Sosnowiec, and that is where he died. Another one was the Holy One, R' Moshe Mintzer, a wondrously wise Sage, who spent all of his days in Torah study. He was a merchant in Vienna. In the end, the Brown shirts got him, old and weak, and he was sent to the Buchenwald camp where he was tortured until his pure soul gave out. The last one of them, R' Aharon Brumer, resided in the town of Kamionka. This Aharon exhibited a sharpness of mind beginning from his childhood, and put his hand to the research books. Neither he nor his father were favorably disposed to the Hasidim.

[Page 274]

This Aharon had a great influence on our Benjamin. Both of them possessed a love for casuistry and innovation, which prompted Benjamin to write. In the Bet HaMedrash of Zolkiew, his writing can be found in the margins of the book of his innovations, in the laws governing Khalitza and Yibum[5]. His scholarship was literally legendary. His writing of chapters of learning continued. He did not stop except for two or three hours, to achieve completion within a day or two. Benjamin told me that he took a minor recess for a few minutes when his mother came and brought him some pears to revive his soul. Once, he continued his story, he was sitting in the Bet HaMedrash studying, when he suddenly felt a contraction in his heart, and very much wanted to eat something. He knew what awaited him at home, some porridge, prepared in tepid water, but when every body extremity is shouting for food, even a porridge of this sort is a desirable meal. He put down his Gemara and went home. It was two o'clock in the morning, after midnight, and while walking he heard a sweet voice, the voice of his dear friend Aharon, who was studying with intense fervor. He stood still, and his heart spoke to him: hey, Benjamin, you are going home to eat, and here, Aharon sits and studies. Benjamin returned to the Bet HaMedrash and began to study like a burning flame. However, after two hours, his hunger returned. And again, he put down the Gemara and walked home. And here, Aharon was knocking on my window. Benjamin. Get up, it is necessary to get up and go to learn.

Halakhah came to him in its essence from the atmosphere of the air in his hometown. Nevertheless, the center of the glorious Haskalah that came burdened from the past, yet from his springtime days, Hasidism had spread out over him with the ferocity of conquest. The city ultimately was captured by Belz and its courtyard. The Maskilim and also the Mitnagdim stumbled, like depleted extremities. The final point of deterioration came, perhaps, that very Sabbath day, when the Rebbe of Belz came to the city, and his Hasidim asked to lower him in front of the Holy Ark in the Great Bet-HaMidrash. It did not matter that the Mitnagdim closed up the premises with a lock on the gate. The concept, ‘It is time to worship God,’ prevailed, and the Hasidim broke off the lock and the latch. Prayer in the Sephardic style and the sound of musicians was heard emanating from the building. When groups of Mitnagdim became too frightened of what had taken place, the deed was already done, and the cry of disappointment was heard in the market. Gevalt! Ashkenaz has died.

[Page 275]

There was another worthy group of Mitnagdim who served as support for the remnants of the Maskilim. A pact that had been agreed upon between the Mitnagdim and the Haskalah at the beginning, out of their joint fear of Hasidism, that had been displaced by the rise of the Haskalah, returned in effect, and was reaffirmed by the signatories of the pact on both sides. The tradition from the days of the רנ”ק and R' Zvi Hirsch Khayot glittered in their final shining. The groups who drew nourishment from its fountains dissipated, like the last of them, wandering from near to far. Among them was R' Hillel Lechner, from the Jews of the רנ”ק who resided in Lvov, and others like him. This cohort of influence grabbed only a small part of the city's youth. One of them was Moshe Mansch, whom the Hasidim called Moshe the Dog, because of his jokes. For example, when he said: So-and-so who had a pair of boots taken from his shoe merchandise and hung them in the gateway to his store; or so-and-so who deals in woven goods, a piece of weaving was taken and hung in the doorway of his store, a Rebbe who deals in Hasidim is obligated to hang a Hasid in the entry to his yard. However, if all of these lines of influence were put together, it is our greater responsibility to make more prominent the personality of R' Yehuda Meir Maimon, whose fate is similar in a number of ways to the fate of Grill.

He was a wondrous genius, and the Úlite of his generation saw him as someone above them in fluency and sharp-mindedness, but he produced little. It is possible to find his sayings, sealed with his real name along with his pseudonyms in Fountains of Water. He was a close friend of R' Zvi Hirsch Khayot. He wrote in other cities where he resided, in Lvov, and Zhurbano. He recalled what he had heard from him orally, and found a way to reach the Jewish scholars in the west by writing and an exchange of correspondence with them. He received some notoriety for his letter to R' Yekhiel Mikhl Zakasz. As he stood on his own and traveled westward, he became friends with Zechariah Frakel and Zvi Gertz, who lavished him with respect. The wonder inspired in him by the form of Judaism stopped being a matter of life to him, and became a matter of Diaspora matters. But with his return home to the east, he lived again in the wisdom of Jewry. He quietly stated his responses as if no one saw that he had returned home. He returned to the life in his house, to traditions and customs, to his clothing, and he continued to write his observations. Most of his material were explanations of the Tanakh and Talmud, but occasionally he wrote about other subjects, for example the chronology of the Crusades. As he had an impediment, he did not speak. He ended his days in poverty. He had become a Maggid of R' Shlomo Buber, and he lavished his hidden energy in the research of the Medrash of that same Sage. The things written about him by R' Shimon Bernfeld were beautiful. He cited him in quotation marks, and it was recognized that this was the will of the returned prodigal, and he publicized them in Reshumot.

It appears that R' Yehuda Meir Maimon was the only one in the city who saw himself as worthy of taking over the wonder of the attributes of Grill. One time, he and Grill and R' Moshe Prizmont called Moshe'leh Huvnover, the greatest comic in all Galicia. Huvnover was also a wondrous Sage, and they engaged in a casuistic discussion of Torah. Grill would be impressed by his lightning flashes of fluency. (רי”ם)[6] Maimon saw that the opinion of the youth was vulnerable to seeming arrogant, and said to him: ‘Benjamin, you are talking yourself into thinking you are able to learn.’

His friends were in awe of his spirit. His manner was not one who showed a surfeit of joy, but his humor sparkled with jokes, banter and the stories of events, especially about his parents, and of his city and its personalities. Or he exhibited a black terror, for its oppression of the soul.

His friends loved him to a fault, especially Zvi Peretz Khayot. They respected each other, and each knew the other's mettle, even Grill. Though he loved his friends, he didn't particularly respect them, and after many years he would say in all frankness, that the Rabbinical Seminary in Vienna where he studied was full of boors. That was, except for the grandson of our Rabbi, (meaning R' Hirsch Khayot), who remembered almost the entire Shas. But this attitude did not keep him from seeing the youthful camaraderie that had come together for the first time in that seminary, as a truly interesting arrangement, since most of them were made in each others' image. There was someone who said: we are first-year students. Everyone whose son was original, was like a drama to himself, even in a tragedy to himself, as if Grill limited him in a precise fashion.

After he lived in Lvov for a short while, studied at the Rabbinical Seminary in Vienna, and moved around several times, he went to Bern in Switzerland and where he received the title of doctor. In that same period he began to write analyses and compilations.

[Page 276]

One seeking to follow the path of Grill in a written form of his oral tales from his young days, should read his novella, R' Mottl Analyzer, in which he published his sayings and stories, The End of Time. This work is first a story in novella form, on his oral exposition on the means to achieve improvisation. It was his custom to speak to his comrades, and afterwards they encouraged him to put his talks into writing. Dr. Meir Geier, who was known as an activist and speaker even though he was personally a simple man, told that one time Grill responded to the request of his friends by saying: ‘My comrades, now the known feuilleton has arrived in a publishable form.’ His friends sat with him, and he produced a chain of ideas, and read from research that was light and revealing. In the end he grew disinterested, and joked about it all. Perhaps the destiny of this paper was the same as the destiny of R' Mottl Analyzer. But his friend, the Sage Michal Berkowitz, saw his intent and said, ‘Part of the writer's fee for this novella had already been paid, and he is paying the fee for recording this on paper, which he nevertheless paid out of his own pocket.’

The novella is based on a slice of life in the town, especially in its Synagogue. The characters in the story are R' Mottl, the narrator, a strong truth teller and a pillar of light, Zalman Czipkineyzil, one of the pot-stirrers in the town, who did all the despised work, such as the incident of bribery in the selection of a Rabbi, and three of the synagogue Gabbaim, especially Lipa Sheretz, a licentious and hypocritical man. It is certain that many lines in his story are taken from life in his birthplace. And it is appropriate to recall that Grill remarked (and it is an example of a saying of the sort that would have been spoken by the רנ”ק: ‘I know three heads of the community in Zolkiew: one is weak, one is a fool, and one is a prevaricator. Our community stands on these three pillars: on the power of the first, on the wisdom of the second, and on the tradition of the third, but the way they mark their path makes them examples.’ The subject of the novella is the custom of criticizing the poor. And the porter fought it in a manner that he calls himself to task. In the end, his protagonists declare him to be insane and that is the way he is perceived in the city. But the path of the story raises the essence of the issue above the episode. It is the tragic struggle of the lone person, loyal to the truth and to tradition. The rulers, and those who set the tone, are untrue to the truth and the tradition, and step on them in their coarseness. Truthfully, what is the difference if the field of battle is in the same village of Novorg which possesses fountains of a medicine whose basis is untrue. Or, in that same Jewish town which possesses a synagogue, whose behavior is to deceive. It is especially so that the opposition in the story before us, is between the champion and those around him.

Its members and friends selected a Rabbi to lead us in the cities of Austria. But their way was not the way chosen by Grill, and even though there was conflict in the foundation of the schism, he fled from the perspective that was opened before his eyes. He did not have the loyalty to return, because he did not have the strength to try new experiences. The path of Gedalia Shmelkes looked to be close enough for his purposes. The path of R' Zvi Peretz Khayot seemed too tragic for him, and the core of the issue did not appear significant enough to quote Sophocles or Aristophanes. I see in this what I heard directly from him, and it appeared to me as an inferred explanation, in a conversation we had on a bench in the garden of his birthplace. I reminded him of the sorrow of his friend, my Teacher, Yehoshua Ozer Proust, who repeatedly said: ‘the young and the old who built on it, the greatness they built was not realized.’ Grill said: I understand what you say. The remnants of Proust give me the feeling that my sustenance is not according to its order, since I sustain myself with a plain hand. But to forgive them, are my friends all extending their hand like that of the schnorrer? For who is a schnorrer if not someone who takes without giving? The Temple community is unwitting because their Rabbis are their friends with a handsome salary. And don't all of them give their salaries as charity? Who is gullible and says that the Úlite who pray at the temples feel some sort of gift of exchange. What sort of gift are they getting from the hands of the Rabbis? Certainly there is a difference. They are my friends. They take their pay cynically, on the eve of every month, with a check from the bank or by mail. I received it ‘retail.’ There is no oversight, but rather, as an attribute of mine, it pleases me to know what I eat and from whom I get my food.

[Page 277]

The role of a woman is not missing from the book of his life, quite the opposite. The love of a woman who was deceived was like a deciding foundation attached to other foundations in his soul. There were those who worked to marry into it, and especially Yaakov Shmuel Fuchs, the author of HaMaggid, in Cracow, who asked to marry his step-daughter, Sarah-Leah Shudmack the daughter of a well-known family that produced Maskilim and the first Zionists in the city. The engagement of the couple was publicized in his newspaper, and Grill began this period of his life. These were the first years of the beginning of the century in which the attempt was made to follow the set path of life and work, and it is possible to add that the most important trajectory in his experience was his desire to have a family.

But no man like this will build a family, and the situation quickly unraveled. The editor worked to draw his genius son-in-law to his newspaper. On days that he would recollect his writing he would say: ‘Don't keep still, because I wanted to write, and never wanted to write, and whatever I wrote I did so by forcing myself.’ His inner opposition to writing stands out mostly in an event with his friend, Felix Farlash, the known researcher on Holy Writ. Farlash was a Rabbi and a Professor in Koenigsberg, and for a short while at the University of Jerusalem, who sent Grill a compilation of his works for purposes of reading and assessment. Grill returned his assessment with great acuity, but his letter trampled on it in the aftermath of the writing. In the year he engaged in the work in which the Zionists were involved, to spread the Haskalah, especially in the way of the Toynbee style, we see Grill in Vienna among the lecturers, more set in their ways, and the issue of his talk, which was an explanation of the Torah portion of the week, was equally set in its ways. These expositions drew a large audience in assessing the first Jewish Toynbee presentation in Vienna that was widely publicized, and those attending said: ‘From the lectures of the last several days, it is especially worth noting the brilliant explanation of Dr. Grill.’

Between June and July of 1902, Grill left Vienna and settled in Lvov.

[Page 278]

His acquaintances and followers in Lvov helped with several drafts to set him on the path to complete his writing. First, his friends, the young Zionists, sought to assist him as well with the work on the Toynbee style that they had founded in their city. Grill responded to them with a lecture on the worth of the Talmud in the past and present, and also on the ranks of the Jews of science. He responded to them with a lecture on the Tanakh and insights about innovations, this being an issue that aroused a lot of polemics in that time, the confusion of Babylon. Regarding the matter of the connection of Grill to the criticism of the Holy Writ, Dr. Chaim Tartakower sat with him because Grill was the one who was alerted first to the spirit of enmity to Judaism and Jews who reached out to the gospels of the Protestants. And it is necessary to remember that Grill behaved like a cultist in Germany and towards Germans. There was an excessively belligerent Hasid in him. He did not conceal his brilliant view on the issue of Jew-Hatred, which he saw as a tendency submerged in the soul of the primitive German.

Those who appreciated him worked hard to draw him near to Seekers of Peace for Zion, which was founded by R' Yom-Tov Lipa Schiff, the father of R' Eliezer Meir Lifschitz, who was one of the Zionist leaders. He went to the Zionist Congress and was even a member of the active Zionist committee. He was on Herzl's side in the dispute between Herzl and the Galician Zionists, and he was one of the first speakers. This group, which later changed its name to The Hope of Zion, had interesting types of people. Y. Perlberger, a scribe, and full of ideas, did not understand all that was being added to the new Hebrew literature, and he prepared a list of the terms of Hebrew commerce that were used in letter exchanges among merchants in Brody. A few of them were accepted by the Language Committee in Jerusalem. Grill would expound in this group, but he didn't have a special issue of interest in the group itself, its direction, or its people.

His old and new friends worked hard to turn him into a teacher, and they appointed him as the Principal of the Khinukh LaNa'ar school. It was a one-of-a-kind institution as it was the only Hebrew school, not only in Lvov, but in all Galicia. It had its ups and downs, and the basis for teaching Hebrew grew stronger because of efforts by its leaders, Dr. Meir Munk, and especially Yitzhak Evven, a man from Rosvodov. Evven was a Hebrew writer who became known later as a refuge for Hasidic stories which he published in Jewish newspapers in America. This school fought a difficult battle to survive in the face of two fronts of opposition: the assimilationists on one side, and the strictly religious on the other. The struggles of this school was a concern of the young Zionists in Lvov.

And here, it seems, that according to his direction and ideas, Grill was found to be suitable for this school. The leadership was turned over to him and there even are a few echoes of his work in journalism.

[Page 279]

Those who appreciated him, especially his supporting sponsor, also worked on his behalf in the Jewish community. At this time a library was established by the congregation, especially due to the support of Shlomo Buber, who gave it a vast treasure of books. Its opening was delayed several times until the young Zionists finally became involved and publicized week-by-week questions and explanations in their newspaper in regards to this issue. Their agitation led to the opening, directed by Gershom Bader. The books in the library and valuable handwritten manuscripts were a blessing. Many hoped that Grill, who was given an opportunity to give a lesson and was revealed to be a magnificent teacher, would be appointed by his supporters and sponsor, to a chair to do research in the Talmud. The opening lecture was given at the beginning of 1903. A compendium of these lectures was called: A Course for the Study of the Talmud, and took place twice a week, Mondays and Thursdays, the hall on ul. Stanislawow 5. The lectures attracted many listeners, and the perception of these lectures, even on matters of grammatical research, was akin to the improvisation of songs. But the days of the lessons did not last for a long time. Even with the large salary that its supporters paid for it, eighty gulden a month, it was not enough to provide for expensive wines and cigarettes, and was not able to permanently continue.

The short period of creating order and permanence was nothing more than a hiatus between what was in front of it, and what was behind. The misuse and taking of provisions without pay, the groups that stood by it as benefactors, especially among his friends, and more precisely from among the mothers of the membership.

Vienna, understandably, was most favored as a place of concentration for these peripatetic people. His friends, who were less well-informed than him in facts and understanding and poetry, had their reputations spread in the world as informed people, preachers and activists. This was what made Galicia stand apart. Grill, the blessed genius, was based in a coffee house on Leopoldstadt, where he was known to sit and tell jokes. There was no embarrassment to his simple approach which became his art. He even took pride in a form of agility that he had developed for himself. His table in the coffee house became a focal point for those who were drawn to the art of the tale and to his humor. His followers would congregate to consume his stories. Besides paying for the pleasure of his humor with their presence, they also provided a few coins.

In his old age when he returned to his birthplace, Grill took pride in being a schnorrer. Addressing this he said:

‘I do not envy any person except one, and who is he? The Tall R' Meir who goes to the cemetery, and hires himself out to recite the Kaddish and the like. Go out and see how extensive his skill is. A wealthy man left by train from Lvov with the central purpose to travel to Belz, and because of this he passes through Zolkiew and makes a stop here. Tall R' Meir waits for him at the hotel, and at one time I thought that he came to this same hotel even before the wealthy man left Lvov. Maybe it was no accident that the wealthy man thought to make a stop in the city, and waited with assured patience while on the train, to make a stop in the city. It is analogous to the gathering of Hasidim, that he spent many long hours, and suddenly made a stop and waited patiently for the arrival of the locusts, and never was his assuredness incorrect. With a prophecy that in its substance is like that of the Hasidim, Tall R'Meir's sense of prediction is not found within me, and I envy him.’

[Page 280]

During the World War, Grill did not feel obligated to serve the Kaiser, and he did not respond to a call to the military. He decided that he would hide himself, and his choice of hideout was in a public place, such as sitting in the Viennese restaurant of Rapaport. It was a place of assembly for his countrymen, refugees from Galicia, and his balebatim and guests were assisted by him as if he were a youthful emissary, who performed his mission for the cost of a meager meal. That was so, until he was seized and subjected to severe torture.

The time of his military service was kept in his memory as a form of a shameful experience. Certainly, as a soldier he was not made to engender spiritual contentment in his superiors. He served, not from the warmth of loyalty, but from the cynicism of idleness. His supervisors were sort of tortured by his behavior. They did not attach any significance to what he said, because he was like a haven for pacifism and Zionism. Grill sought several legal means to be spared military service, but could not find any. At most, he was accepted by Rabbi Aharon (Adolph) Schwartz, who had the ability to discharge him through the gift of a certificate as a candidate for the rabbinate, but he refused to do this. Perhaps he did not want to give the certificate to an abandoned and sloppy person, or because he hated Grill. Grill was in the habit of saying: ‘hey, military service. I evaluated the traps in this world, my bad deeds, and I erred in both.’

He served his military service in the city of Gleichenburg. To a large degree his diligence and focus was recognized even though he never took his bayonet out of its sheath. On those days when he was compelled to take it out, he couldn't. Not him or others who were stronger than him, because his bayonet was stuck as if it was glued in its sheath.

At the conclusion of his wandering he returned to the city in which he was born. He sat there, and went out infrequently for only a few hours. His comrades, who were the heads of the congregation, attempted to get him to reform, but it was in vain. The man resided in his city, in which the balebatim supported him with excessive affection. His abilities were as they were before in his fluency, sharp-mindedness, and in particular in the art of storytelling. He told a story about a fellow scion of his city who avoided military service, and was seized and captured. His fellow townsfolk hired four people, two of whom went into the saloon opposite the prison and removed the prisoner. His stories were a wondrous form of art. His friends from the days that he taught, relate that his talks were about his expression of pleasure in the creation of the world, about man, about fables, art, of nations not to stray on a side path, and the analysis of ideas. Every image from his stories drew an outstanding impression on his listeners.

[Page 281]

The passion heard in the force of his storytelling continued even in the period of his decline, and he responded to a request to speak about Herzl in the synagogue of his city. He did not make an assessment of Herzl, or of his work. He spoke about Herzl's funeral. He said that the funeral passed like a tangible experience in the hearts of the listeners whose souls were impacted by it. The power of his storytelling was revealed again, when he came to tell about events, which consisted of chapters of his experiences. As an example, he spoke about the first opera that he heard in his life. He informed his listeners that he didn't hear a story, but heard the opera itself, the vibrated rhythms, and the clear voices of the song and music. Even the substance, lost in the thickness of faraway places, was heard. The story of the opera was great and profound, like that which is heard from the Bima.

In the fortress of the city and the depth of idleness, he was the subject of criticism. At times it seems he was overly detailed in the matter of forbidding to leave the head uncovered. He said: ‘you certainly think that I behave this way out of respect for the Torah, but in truth, I behave this way out of respect for the core. I am forewarned against exposing my head, not because my brother Yaakov, who is a Dayan, and supports me with the accompaniment of The World to Come, but rather because of my sister Chana Gittl'eh, who sells produce in the marketplace, and supports me with the produce of the Present World.’ Grill would stand in the doorway of the saloon in his city and mock himself. This saloon had a reputation, not because of its atmosphere in those days, run by R' Simcha Ungar, but because of the atmosphere within with the presence of R' Nachman Krochmal. Grill was a rare guest in this house, and Simcha Ungar would fill his cup with the best of his stock of bottles. He would point to the house and say: ‘in this location, Krochmal, may his memory be praised, taught us Latin, Greek, Syrian and Arabic. Here in this very same house, Grill, may his memory be in Eden, taught us Latin and Greek and Syrian and Arabic, and many other things.’

By mocking himself, especially in front of his audience, one could see an aura of affection and compassion. Essentially he loved all men, especially the simple people. The hunger for learning that began in his childhood became stronger. He would say: ‘In my current state of learning, I explore very deeply into the body of the Halakhah, and I now understand more about what I learned than I had previously understood.’ He would be disturbed if it appeared to him that he did not exactly remember an issue he had learned in complete detail. There was an incident that took place in the marketplace, at a time when he wore half a beard and was half clean-shaven. People wondered about him, and he said; ‘the barber is working on me and is shaving me and I need that moment to look into the issue of the study of Torah, the memory of which rose before me. I will wait until the barber finishes his work, even though it is certain to me that I will, in the meantime, forget the issue, or I will go to research it and because this old man certainly will not forget.’

He was unable to speak In the final two years of his life, and so he was more inclined to listen. It is possible to infer the state of his spirit during these years, from a small letter he wrote. From time-to-time he saw himself as a sidelined star that shone in the dark. Here are the words of the letter written with difficulty and negligence:

[Page 282]

Your friend Benjamin Grill.

Many heartfelt thanks for your affectionate lines and also on conveying the greetings of peace from the Chief Rabbi Ehrenpreis. In the decade of the nineties, he was the first to teach me Latin, doing it as a mitzvah. I have no special news, except that I grow older each day, and fumble around more. Many blessings to all of you.

During these years, his tendency to study grew stronger, and occasionally he went into the Bet HaMedrash where he learned with great diligence as if his childhood years had returned. He was ridiculed as he continued to wander the streets of the city, and he mocked others in his heart. It may have been sweet for him to recognize that he saw the entire city as a coterie of fools that were dear to him despite their gullibility.

During the months before he died, he felt his heart rebelling against him as he sat in the hall of the Jewish casino in his city, and beside the stove in his house. He said: ‘My heart, my heart, why do you torture me thus? I will not stand like a Czar and fight for what you want. I proclaim my complete capitulation.’ A number of days close to his passing, his friends and neighbors sensed his mind was not normal. They asked him: ‘Mr. Doctor, why do you not sleep at night?’ He answered: ‘Where does sleep come from, and why is it decided that one sleeps at night?’ A neighbor wrote a detailed letter two hours after Grill's funeral, on November 26, 1936, which described his death.

The night before this, Grill became ill and went to his neighbor, the watchmaker Mr. Zwerin, at four o'clock, and woke him up, to save him. The watchmaker began to deal with him, but his malady did not leave him. In the morning at nine o'clock another neighbor, R'Moshe, came in, and found him sitting beside the stove, half-dressed, and his breathing more labored than usual, and Grill said the following to his neighbor: My good friend Moshe, this past Sabbath, I drank my last cup of coffee at your house, and I will not be your guest ever again. Today I die. R' Moshe began to coax him with words, and the sick one joked and said: Moshe, ahah, I have been drinking coffee at your house for eight years. I did not miss a single Sabbath. You are the best of my friends and you carry a blessing, as you came here immediately in the morning. R' Moshe left him and said: I will return in the evening. He replied with terrifying irony: Yes. Yes. At noon, the son of the Rabbi came to him and requested to take him with the Red Cross train to Lvov. He agreed to this, and began to get dressed, sitting by the stove. At that moment he deteriorated, and in a minute his soul departed from his body, and the prayer he prayed for his entire life came to pass, so that he would not be immersed in illness.

The writer added that Grill's humor in his last days was like a pile of hundreds and hundreds of sharp thoughts. On the last Sabbath, he came to the Bet HaMedrash to hear the eulogy for Yehoshua Tohn and said to the one giving the eulogy: ‘Listen to the silent tongue.’ The day before his death when he felt badly, he came by himself to the Rabbi and said, that if I die, I am leaving four hundred gulden – one hundred for the servant in the Rabbi's house who cooked for him; one hundred for whoever will recite the Kaddish on his behalf; thirty gulden for the one who creates the style of his headstone, and the remainder for burying implements and a headstone. The writer concluded: to say, at the end he did not die in someone else's burial shrouds, that is the end of an insightful man.

[Page 283]

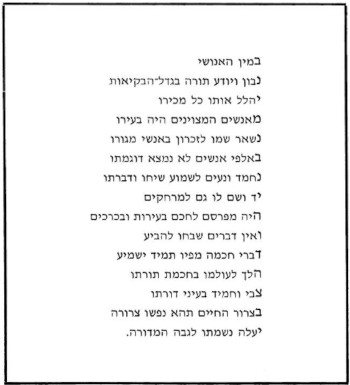

R' Avraham Yaakov Wildman, one of the elders of the remaining Mitnagdim in the city, was asked in the will to compose the wording of the headstone, and he sat down and did his work. And here is the style regarding the Rabbi and Sage R' Benjamin ben Yehuda Zvi ז”ל called Dr. Grill:

|

|

| The Innocent Style of a Headstone – The End of a Song[7] |

Translator's footnotes:

By Yaakov Ne'eman (Neumark)

On the top of a hill, across from the ancient fortress-city Zolkiew, a grove spreads out across the surrounding area where the residents of the surroundings could tell a myriad of fables.

|

|

| The factory in ‘HaRe'i’ where the scribe Joseph Chaim Brenner lived in 1908 |

The grove was wrapped in mystery for many generations. The caves that stretch from the grove to Zolkiew, the locked fountain behind the iron gate, and the wondrous alignment of the trees, were all part of this mystery.

Joseph Chaim Brenner lived close to this line of trees during the months of June-July 1908. He was an ‘undesirable man’ because he was born in Russia and was pursued by the Czarist régime as a rebel against the monarchy. ‘With the sunlight on me, and with the grasses of an alien land, I lay down and consulted our literature and the world in which it exists.’ It is with these lines that Brenner opens up his excerpts from the world of Hebrew literature (Revivim, Volume I).

I came to visit the house in the same grove in 1931, in which a family of farmers lived. I found an elderly lady, about seventy years old, who spoke about ‘the Jew who lived with us many years ago.’

She told me that she became aware of the murder of Brenner, by Arabs, through the Jews of Zolkiew.

He was a precious man, she said, and her voice quavered with emotion. There are many things, but my memory fails me. I think about twenty-five years ago, this Holy Man lived in our hut and played with our children. The man loved nature and the resonance of the grove. He would vanish during the day, and return to his room towards nightfall. He had burning eyes, and we saw that he was a Man of God. On the Sabbaths, the Jewish youth of the town came to visit him, and they conversed a great deal. Despite this, he was a lonely person, always alone, but with his many books.

By Rachel Kaldor (Eikhl)

An image that stands out for me, from the town of Zolkiew, is that of a modest man, who, along with those who were close to him, followed the Aramaic saying of חז”ל . This man was R' Avraham Dov Eikhl. His black, perceptive eyes conveyed sorrow and sadness, joy and mischief. His heavy eyebrows that stuck out over his nose, conveyed a sort of external sign as to Avraham's sharp scholarly mind.

He was the oldest son of a rural Jewish Maskil, from the Eikhl family. His mother was an emotional woman, sensitive and good-hearted. Her heart loved everything alive and blooming. As a youth, Avraham already stood out by his quick grasp, profound thoughts and the skill to express his mind in writing. A religious Jew and ardent Enlightened person was able to persuade Avraham's father that his son, Avraham, was destined to become one of the élite of Israel, and it would be a sacrilege to allow him to indulge in secular studies. Because of this, the boy was guarded from every direction, so that he would not burden his mind with a secular book. He studied in a Heder and the Bet HaMedrash in Magierow, a town near his village, and he resided in the home of the Rabbi of the city. The boy experienced only fortunate days. Occasionally he would even provide a release to the teacher of his spirit, in the form of various antics. The youth, thirsty for knowledge, was trapped by the secular teacher in Magierow, and in place of Talmud lessons, he got lessons in German. He spent all of the money he had in his pocket on the purchase of books. One time when his book buying was discovered, his parents confiscated his books. However, he stood fast in his rebellion, and with an unusual dedication and strong will, doubled down on his studies in a number of the books that he brought to hide in the attic.

He became engaged to the daughter of R' Yaakov Patrontacz, a wealthy man from Zolkiew, at the age of seventeen. The character of his spirit and the leanings of his heart led him to seek peace, as was illustrated in the greeting he sent to his bride in a letter to his father-in-law. His words in a letter were: ‘I seek the acceptance of the eagle and that you will enrich the eagle and reverse the course of the decade.’ If you divide the eagle into ten letters, you will get halakh, and if you reverse the order of the letters lo, before you, you have the word kalah (bride) to whom the young man wanted to send his best wishes.

[Page 286]

After his return from the army during the First World War, Avraham settled in Zolkiew and acquired many friends among the Maskilim of the town. His perceptive comrades were Dudl Maimon, a knowledgeable person who attracted followers through his speeches and writings, and R' Pinchas Schwartz, a mathematician with a broad grasp of many outlooks and ideas.

Avraham Eikhl knew Hebrew fluently. He was an ardent supporter of the use of the Hebrew language until it was spoken routinely in his home. In 1923, at the age of 38 he became severely ill, and ‘has not risen from his bed of ink until his death in 1930; it was a severe pulmonary inflammation[1] that allowed the development of typhus in its wake.’ The robust young man struggled with his illness for years but could not overcome it. He suffered during these long years of illness, yet he did not cease his studies and research, especially in the field of statistics, in which he compiled many views. In addition to his intense attachment to precise sciences, he also possessed a poetic soul and excelled at writing in Hebrew and German. The man was religious, and hesitated to address religious issues from a scientific basis. His take on the world was to see himself as a critical agent of truth. He attempted to attain it, to ‘distance yourself from lies.’ Through his dedication to truth and justice he saw the construction of an idealist socialist organization as essential, and a goal, in which it was the right of every man to be free and to work.

|

|

| The headstone on his grave in the cemetery in Zolkiew |

He surrendered his pure soul to his Maker prematurely, at the age of 45. The following is engraved on the headstone of his grave:

A Torah hero in deeds and understanding, crowned in his youth for a long life, he died. The pain was great and profound when this Tzaddik went to his grave. His wife and daughter wept greatly because of the impact of a terrible disease during his life, which caused them their own silent suffering. He lived with his troubles with affection and did not succumb to complaint even when his suffering intensified. Avraham passed away not because he was aged in years, but because of the greatness of his honesty and the purity of his soul and for his boundless patience. May God reward his patience.

The sentence, ‘Avraham came into his years but not old in years,’ was etched on the grave, according to Dr. Benjamin Grill.

Translator's footnote:

By Shoshana Selakh (Herbster)

It would be difficult to record the chronology and memories of our city Zolkiew without recalling a shining personality who sent the rays of her loving and warm soul to all corners of the city. She addressed the sorrow and pain of the needy and was transformed into a figure and symbol of a God-fearing woman. She was not from a rabbinical family. I do not know her secular name to this day, because not once was she called by her secular name; this is out of great respect and profound admiration, whispered by all scions of the city on her behalf, and by every family.

The Rebbetzin Rabinovich is from the Rokeach Family, the daughter of the Great Rebbe and Gaon of Navria זצ”ל. She was a fountain of good deeds, suffused with Torah-Mitzvot, from which other women drew their God-fearing nature and initiative. Everyone loved her. It is, however, impossible to count all of her good deeds, and it is not within my capacity to enumerate all of her undertakings of charitable giving, her social initiatives, and clandestine support that she provided to needy people. Her focus was on the suffering of all people living in poverty and deprivation, and who needed the discretion of her help, and not seen by others. The knowledge of her deeds vanished completely with her. However, etched in my mind, I remember her beauty, her appearance and her erect posture. When I was still in my city, I thought this to be the appearance of all the Rebbetzins in the world, but when I went out from my city, and I saw many others, I faced the fact that the appearance of our Rebbetzin and her presence testified to the aura and legacy of Rabbis from many past generations. The Rebbetzin's face manifested a glow of Torah and her inner commitment. She wore a silk brooch, a szterntikhl, over her hair, adorned with valuable jewelry and rare and precious stones. This decorated her white forehead, which was smooth as marble. Her understanding, black eyes poured out good-heartedness to the public. She weighed each word she spoke, all of which came from the depths of her heart. She was tall and lean and wore beautiful clothing. Her erect posture gave her a regal appearance, as figures in the days of Israel's legendary past. She was always escorted by one or two women when she ventured out into the city streets, and attracted the attention of all passers by. Everyone looked at her with admiration and respect, and heartily blessed her.

When she was young, and I saw the Rebbetzin in the street, I ran to kiss her hand. Feeling fortunate, I would tell my mother about these encounters. This feeling of goodness extended to my mother ז”ל, who loved the Rebbetzin with a great unbounded love, and visited her often. The Rebbetzin projected an aura through her appearance, of a boundless good heart, nobility, and Torah learning. All of this was reflected in her face. She was restrained in her speech in that she spoke only for a good purpose. Every sentence she uttered was weighed and measured. I never saw her become angry; she knew how to control her temper. She never shouted at, nor got angry with her children. Any sentence she said was complete, clear, educated and directing. Sometimes it was comforting and encouraging.

My mother considered it to be a sacred obligation to visit the Rebbetzin and receive her blessing. She frequently visited the Rebbetzin on Sabbaths, Festivals, and sometimes during the middle of the week, to tell her of her troubles and joys. These were not ordinary visits. The visits provided a sacred hour for prayer, admiration and respect.

From my earliest childhood, my sister and I were attached to my mother when she visited the Rebbetzin. I stood beside my mother and did not move from my spot. I silently listened to the conversations between my mother and the Rebbetzin. My mother conversed with other women who also came to visit the Rebbetzin, but quietly, as if not to disturb the sacred spirit pervading this house. Occasionally, the voice of the Rebbe, calling the Rebbetzin, would cause the discussion to stop. Then all of the women rose, trembling in sacredness, and carefully looked through the cracks of the tall door: ‘Der Rebbe, Der Rebbe’ and they no doubt blessed him silently in their hearts. When I was seven years old, the Rebbetzin gave birth to her first daughter, Sarah, with whom I occasionally played.

[Page 288]

|

|

| The Appearance of the Women's Section in the Great Synagogue of Zolkiew |

During the Festival of Sukkot, the Rebbe's Sukkah was a place for joy and holiday celebration. The Sukkah was beautifully constructed, and consisted of several rooms. It was a joy to sit in the Sukkah, and to inhale the scent of the fresh green skhakh[1] that stimulated one's sense of smell. To this day, the pleasant scent of the skhakh rises in my nose. In the Rebbe's Sukkah, there was a bed in the corner and a library of his sacred books. The Rebbetzin had her own room in the Sukkah. The two prayed in the Sukkah for the entire holiday of Sukkot. I still remember the special decorations of the Sukkah, wonderful decorations I have not seen anywhere, even here in The Land. The Rebbe and his Hasidim arranged a magnificent procession through the streets of the city to the river on Rosh Hashanah for the recitation of Tashlikh. The procession passed by our house which made my mother joyful and happy to see this, and to hear the voices of the singing Hasidim.

Translator's footnote:

By Aryeh Acker

In the latter years of the 19th century, the family of Yehoshua-Zvi, son of R' Israel Acker, a young man with deep religious emotions from the Hasidim of Husiatyn, took up residence in our city. He and his wife, Breindl-Rivka, a daughter of the Tzishniver family, made their living from a concession where they sold tobacco and cigarettes. At first, R' Yehoshua-Zvi prayed in the Belz Kloyz, but his modern dress and his behavior, which was not like that of the Belz Hasidim, did not find favor in the eyes of these Hasidim, and he decided that there was a need for a House of Prayer that was willing to accept worshipers like him. He was surrounded by fiends of the same mind, such as: R' Aharon Dagan and his sons, R' Nissim Stern, R' Avraham Stern, R' Baruch Stein and his son-in-law R' Eliezer Litman, R' Israel Mellis, R' Pinchas Schwartz, R' Emanuel Kaufer, Moshe Baruch Katz and his son-in-law, the Fleshner brothers, R' Shammai Rapaport, R' Joseph Deutscher, R' Moshe Cohen and others. Using their own skills, these men erected a synagogue in the name of the Tzaddik of Ziditshov. R' Yehoshua-Zvi, in particular, put in a great deal of time and work to complete this building.

After the building was erected, the Ziditshov Kloyz went through a period of growth. Many balebatim joined the Kloyz. These men sought the closeness and warmth that pervaded the Synagogue, reflected by Gabbaim, especially the Head Gabbai, who was called by the affectionate nickname, R' Hershel'eh. They continued their study of Torah on the Sabbath and weekdays. Also, many youths and balebatim used to come from the Belz Kloyz to the Ziditshov Kloyz, in order to study there. I recall the Cantor, R' Israel Mallis, R' Aharon Dagan, R' Nissim Stern, and R' Avraham Stern, who led services and inspired the elevation of spirit among the worshipers. The songs sung during Shaleshudes on the Sabbath became famous. The Rabbi, R' Pinchas Rimmelt was a permanent guest at Shaleshudes, and the principal subjects for discussion were the tales of the ADMoR'im, and the Great Torah Sages that were told between songs.

In the process of managing his usual businesses during the week, R' Yehoshua-Zvi, together with the Brudinger household, established a Cooperative Bank, in order to extend credit to the general populations of all faiths. In particular, the farmers in the vicinity came to obtain credit at a good rate of interest. In addition to this, R' Yehoshua-Zvi extended interest-free credit to the merchants and storekeepers in the local market. The credit was used for trips to Lvov for the purchase of goods.

A small crisis developed in the life of the family in 1908 when a local Jewish man took away the business from the hands of Yehoshua-Zvi. However, the family recovered quickly. The excellent relationships the family had with the local residents helped them to recover from the blow of this loss, and they continued to manage their new commercial business successfully. As the children grew, they helped in the business, but tended towards Haskalah. Even though R' Yehoshua-Zvi was an observant and traditional merchant, he was not disturbed when his daughter and son joined the Zionist groups in the city.

During the First World War, the Russians reached our city and they demanded that the Jews establish a national commission, and R' Yehoshua-Zvi was elected as a member of the committee. Many refugees, plagued by the Russian takeover from the towns of Mosty'-Wielkie and other places, reached Zolkiew. The Russians remained in our city for two years and the Jewish populace suffered attacks from this conquering army. The national commission was constantly on alert. It worked for the good of the Jewish populace, and excelled in swiftly providing aid to the needy. After the liberation of the city from the Russian conquest, the Austrian government drafted R' Yehoshua-Zvi and his son, Moshe, into the army. R' Yehoshua-Zvi served as an officer of the mail in Vienna, and Moshe in Hungary. Very slowly, the family began to restore their businesses that had been torn down. The oldest daughter, Shaynd'eleh, was especially adept at managing the store and restoring earnings. After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, there were very strong clashes that took place between the Ukrainians and the Poles. During that time, R' Yehoshua applied himself to community matters.

The Zionist movement prospered during this time period in our city, as did interest in the Hebrew language. The Acker family members were very active in this. The notifications they placed in their store window to sign up to learn Hebrew drew in many young people. Interest in the work of the Zionists grew stronger until it drew a sharp reaction from the fanatic Belz Hasidim. A large delegation from the Synagogue in Belz appeared on the Sabbath in the synagogue of the Ziditshov Hasidim which delayed taking out and reading the Torah scroll. The Belz Hasidim remarked strongly that the Zionists were leading the youth to convert, but did not have the nerve to confront R' Yehoshua-Zvi directly. Some of the synagogue worshipers explained to R' Yehoshua-Zvi that it was he who the Belz were objecting to, because the signs for the courses were hung in his store. R' Yehoshua-Zvi replied that he would not stop his son or daughter who worked in the store from hanging up the signs for the courses. He also said that he would send his daughter Reizl'eh to a Hebrew class, so that she can understand the blessings she said every day after meals, but he would not send his son Aryeh, as he studied in the Belz Kloyz. And with that, the chapter ended.

[Page 290]

During those same years, a plague of typhus broke out in the city and some of the members of the Ziditshov Kloyz became bedridden. A group was organized among the worshipers to deliver aid to the sick, and R' Yehoshua-Zvi was one of the volunteers. Despite warnings from the doctors that volunteering for this would lead to a spread of the plague, and that he should close his store because of his visits to the hospital, R' Yehoshua-Zvi continued to work with the volunteers. Well, the doctors were right, and R' Yehoshua-Zvi became infected with the disease and died on 18 Adar II 5669. (March 3, 1909.) The national committee and the congregational committee called for the sitting of mourners, and decided to donate a place of honor in the congregation's cemetery for his burial. This was because of his good deeds and involvement in community affairs for the general good for no reward, both day and night. All of the residents from the city participated in the funeral. Stores were closed as an indication of mourning, and he was eulogized by several personalities, among them Rabbi Rabinovich. During the days of morning all segments of the population came to pray and visit the house. Even Christians, Poles and Ukrainians came to express their sympathy for the loss incurred by the family.

During all the years in which family members were engaged in commerce, they also found time to attend to community needs, especially the son, Moshe, who was committed to collecting funds for KK”L, and was active in the Kultur Verein. Moshe was respected in the central institutions of the movement. He founded a Hebrew language kindergarten and a Tarbut school together with a number of other activists. He also negotiated with the Geulah group regarding the acquisition of a parcel of land in the Land of Israel, but the matter did not materialize.

A training group was organized in the city's glass factory in 1930. The participants consisted of young pioneers from the Freiheit organization, an offshoot of Poalei-Zion-Right, which was tied to a united kibbutz in The Land. This group was part of Kibbutz Dror, which had been established earlier in Galicia. The conditions for survival for these workers in the glass factory were difficult as the factory paid very low wages. Help arrived from Moshe, the son of R' Yehoshua-Zvi ז”ל who, together with a number of activists organized hundreds of packages of food for the members of the division.

|

|

| A Side Street in Zolkiew |

By Y. D. Zahar (Zubl)

Here I will relate a story about two families in our city who were united by the bonds of marriage and became one. It is my father's family, the Zubl family and my mother's family, the Bandel family. Both of them were rooted in the city of Zolkiew.

My father had two family names: they were Zubl and. alternatively, Brenner. Jewish couples were often married only in accordance with Mosaic Law, and not in accordance with Austrian Law, and because of this, the children used their mother's family name. With the establishment of Poland as an independent nation, he was legally allowed to change his name to Zubl.

[Page 291]

My father was half-orphaned, and as was customary in those situations, his family expressed a chilly attitude toward him, from his childhood. This relationship was also passed on to the grandchildren. To do justice to my grandfather and grandmother, in general they were not people of feeling, and warmth was missing in their home, even between themselves.

The only ones who were tied together in the family were my brother Shammai (Dzhunik) and myself. During the First World War, in the years of 1915-1918 when we were 6-8 years old my father was a soldier in the army. My mother, brother, and I lived with the Bandel grandfather. On Sabbaths and Festivals we went to the Great Synagogue of our grandfather, Shmuel, in the morning and prayed in the Ashkenaz style. Our grandfather watched over us to make sure we prayed diligently, and after the service was finished, we accompanied him to his house. We blessed the wine and brought cholent from the bakery. In exchange for the food that we received, we were asked to sing. We knew a meager set of Yiddish songs, and we sang as a duet, sometimes from under the table out of shame and modesty. After we finished singing, we returned to grandfather Bandel Zubl, who was a Hasid and prayed with Rebbe Rabinovich. Prayers ended late there. By the time they were ready for a repast, my brother and I were ready to eat a second lunch. There was a non-Jewish servant in the home of grandfather Bandel who warmed the meals, despite the fact that this practice was not so Hasidic. Here we were liberated from singing. Year in and year out, we, the grandchildren, would get new outfits for Passover from grandfather Zubl.

Grandfather Zubl had a store that manufactured ‘podsyny.’ Grandmother ran the business. She traveled to Vienna, Budapest, or nearby Lvov, to buy materials. Grandfather was a quiet and refined man, with a long white beard, who accepted whatever his wife Ruth provided without reacting to her actions.

My grandfather's family was wealthy and their wealth increased even more after the First World War. They bought a big house in the marketplace, called Dom Pinski. They opened a second store for manufacturing upon leaving the first one to their son Moshe, who had married in the meantime.

The Bandel family was one branch of the many-branched Israel-Ber Katz family. Grandfather Bandel was a short man, confident, strong and ill-tempered, who sought to lead. He had an inn, Dom Zayazdny, where farmers would leave their wagons hitched to horses, when they came to town on market days and for fairs. Thieves who might have wanted to steal from the wagons were afraid of the firm hand of Israel-Ber, even in his old age. There was a strict tone in his house and the Elder of the family accorded him the respect normally shown to a Rabbi. His grandchildren were frightened of him, even when they grew up. His only granddaughter, Malka Szpitzer, wrote the following about him:

He was a great man with a heart of gold. He had a strong character and was very religious. He was honest without being egocentric. He participated in the Jewish community life of the city. He garnered respect from everyone, was an advisor in the town and was active in the community committee. He organized a Talmud Torah for poor children, and looked after their sustenance, and once a year he provided a gift of new shoes to each child. In order to avoid having the sick Jewish people that were lodged in the municipal hospital eat unkosher food, he hired a woman to prepare food for these sick people in her home. He loved the truth, and demanded it from those around him. His grandchildren loved him, and were awed in his presence, because forgetting morning prayers or to return home late at night, was considered a sin. He loved his family and held on to the four of his children even after they got married.

His oldest son, David-Joseph, studied a great deal of Torah and was qualified for rabbinic ordination. When he was seventeen years old, he married a young lady, and in time, she gave birth to nineteen children. They lived in a house with two rooms and 3-4 children slept in one bed. The children grew up in wretched economic circumstances, and twelve of them died at a young age. The seven survivors grew up and married, but only one, Malka Szpitzer, who worked at the ‘Starostvo’, survived. After the First World War, she married Mr. Szpitzer and they emigrated to the United States.

[Page 292]

David-Joseph had a tobacco store, trafika, opposite the Dominican church. His father, Israel-Ber, had received permission to sell tobacco, coins and newspapers in the store, years back from the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, as a reward for excellent guardianship. We were told about this excellent guardianship in great secret, because during the time of one rebellion by Poland against Austrian rule, in January 1863, while Israel-Ber was strolling outside of the city by way of the Glinski Gate, he saw Poles preparing to come closer. On his return to the city, he told this to the Austrians, who later remembered Israel-Ber's good deed. After the rebellion was put down, he received two permissions from the Austrians. One was for the tobacco store and to make change, which he turned over to David-Joseph. The other was for the sale of salt in Eastern Galicia, which he turned over to his daughter Hoda, the wife of the purchaser, Kurtz in Lvov. The two permits remained with them and their children, even in the country of Poland. The government did not take the permits away from them because they did not know the reason that they were granted in the first place.

His daughter Hoda Kurtz was married in Lvov, and she had seven children. Her situation was very good. The youngest son, though he was called Israel-Ber, was murdered while taking a stroll through the mountains in Poland. Her son Herman, a Doctor of Law, and his family were murdered in the Holocaust. Her daughter survived when she came out of the ghetto. Her son, Macek Morgan was saved, and lives in Poland. Her son Joseph, a medical doctor, lives with his family in Netanya. Out of the remaining children, the daughter Fried'ka, married a rich man in Trombobla. Hanoch, the black sheep of the family, remained a bachelor. The daughter Chaya (Klara), was married into a family landsman and of all, the only one to survive, was Gusta Kluger, now in Tel-Aviv, and the daughter Hella (Hoda) who lives in Warsaw. The youngest son was Shmuel Kurtz, who lived in Holland and made aliyah to The Land. He and his wife died a number of years ago. They are survived by two daughters and a son in The Land, and they are engaged in agriculture.

Israel-Ber's second son was Meir-Wolf Katz. He had a store for machines used for cutting wheat sickarnia. Meir-Wolf was a short Jewish man. His circular hat went down over his ears and almost covered his face. He loved to speak. All of his speeches began with the mention of Maria Theresa, the Queen of Austria in the 19th century, for whom he had a special soft spot. There were always children, farmers and fowl circulating about his house, leaving no place to stand. The second daughter of Israel-Ber, Tzir'l, the wife of Shmuel-Yitzhak Bandel, are my grandparents.

I want to say more about my Bandel grandparents, whose characters were different and unchanging. My grandfather had a good disposition. He was honest, and he loved music. He had a permit to sell salt, which was a countrywide monopoly in the time of the Austrians. It was difficult for him to support his large family. Every time he would get into a different business, he had problems, but he continued to have faith in his partners. Finally, he opened a plant for making concrete, and his son-in-law Reuben Tzimerman, who was a graduate scientist from East Vienna, helped him to manage the business. My grandfather was a Hasid of the Rebbe R' Rabinovich, even though he dressed German style. He read newspapers and also spoke Polish and German. He visited us in Lvov at every opportunity and enjoyed seeing films at the theater, and the opera. He loved to sing or hum arias from different operas, while around the house. My grandmother was irritable, like all the descendants of Israel-Ber who were leaders. My grandmother spent most of her days in the kitchen, cooking and baking, knitting or reading a newspaper. She loved her children and grandchildren very much. My grandfather often became emotional and cried with the same ease that he laughed.

[Page 293]

I do not know how old my grandfather was, when he was shot by the Nazis at the end of 1943, but he certainly was well past eighty.

My mother married my father, Alexander, in 1908.

My brother Shammai and I were born in Zolkiew and lived on ul. Lvovska. My father tried his luck at making a living in Lvov, and worked for a Dutch ship line. Afterwards, he worked for the Cunard-Line. During the First World War, he served in the army, and after the war, the entire family returned to Zolkiew where we spent our childhood and studied in school and in Heder.

In 1921 we moved to live in Lvov, and my father was reinstated to his position at the Cunard-Line upon his return. His situation was excellent because he received his pay in U.S. dollars, thus avoiding the inflation of Polish currency. We, the children, attended the government gymnasium.

Our ties to Lvov remained strong. We visited my grandfather a few times a year, and we came to spend time on the mountain of HaRe'i. At the beginning, we lived in the house of Germans at the top of the mountain. After a few years we bought a villa on the slope of the mountain, where we spent the best years of our otherwise dreary lives. In general, on Sabbaths, our grandparents visited us, and occasionally we went down to the city to their home. Every day, a Ukrainian house maid would come to us with baskets full of food, and we spent our time pleasantly.

In 1934 I made aliyah to The Land despite the pleading of my parents who opposed this. In 1936, my brother Shammai made aliyah and married here. In 1938, my brother Zvi also made aliyah. He came as a student at the agricultural school in Mikve-Israel where he studied for one year. In the spring of 1939, when I became aware of the difficult circumstances my mother was in, I traveled to Lvov, but I got there on the last day of mourning for my mother. My father felt that he would have need for support from his sons, and because of this did not want to make aliyah to The Land. I still had the chance to see Zolkiew and my family for the last time on the threshold of the Holocaust. Nobody understood the extent of the danger that was closing in. They thought the war would be no different than the last one, which was still fresh in everyone's memory.

By Mordechai Astman

Ours was a large family, on both my father's and mother's side. My father's family was engaged in commerce and agriculture. It is a practically unknown fact that a large number of Galician Jews were involved in farming. They were tied to the land, and knew, chapter and verse, the methods they needed to work the land. Despite the fact that all of them lived in the city, many of them had a parcel of land in nearby fields. One part of our family would purchase agricultural products from the nearby villages, with the intent of selling them in the city. However, one could manage only a meager way of earning a living from all of these types of work. ‘Much work, few blessings,’ as the familiar proverb says. For this reason, many of the residents of Zolkiew were forced to wander to faraway places, to North or South America. Even my father, who was born and raised in Zolkiew, was destined for exile because of difficult economic circumstances, and he went to seek his fortune overseas. At the end of the 1920s, he emigrated to Montevideo, Uruguay. It took several years for him to be able to bring his family to him, and this is how part of our family was saved.

[Page 294]

My mother's father, R' Yeshaya Redler, was a furrier. He was a man of good deeds and he had considerable influence on me. He treated every person like a human being, and related with patience to the younger generation in matters of religion. He also earned a good reputation in public affairs as the Chairman of the Furriers Union. He sedulously avoided instigating arguments; he always sought ways to smooth out the conflicts.

I will recall here an episode that illustrates my grandfather's patience, a particular characteristic of his personality. On a Sabbath in August 1939, I was supposed to be in Lvov in order to continue on my way to South America to join my family. In order not to desecrate the Sabbath, it was decided that I would leave Zolkiew on Friday. Briefly, the ‘evil inclination’ in me persuaded me that I should not pass up on the last Friday night repast at my grandfather's home. I asked if I could take some food with me for the trip, with the warmth of the Sabbath in it, as the Sabbath custom requires. I had the temerity to ask my grandfather to agree to this, even though the matter was tied to the desecration of the Sabbath tomorrow. My grandfather gave his consent, despite the opposition of my grandmother. Many, many Jews like him were exterminated in the Holocaust.

Zolkiew made a strong and deep impression in our hearts for all of our lives. The small amount of warmth that we carry in our hearts has its roots there from those days, and would encourage us in life, and new places where we came to live. It was from there that we drew strength for our day-to-day struggles.

Our days of being in Uruguay went by and covered us with longing for our city. And when the staggering news began to reach us regarding the extermination of the Jews, we were assaulted by terror and fear about the fate of our dear ones.

In the last few years, the decision crystallized in my heart to make a trip to Israel and to reunite with the residents of our city from the past. When I made the trip with my family in 1964, I created a center for furriers in order to revive the profession that was so widespread in Zolkiew.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Sep 2024 by JH