|

|

[Page 75]

These changes created difficult economic situations in the city and especially for the Jews. The financial condition of the community was distinctly reduced. The burden of the loans grew from year to year up to the point that people could not cover the interest on the loans that had been taken from the churches and monasteries, where their debts just by themselves ran to 12,075 Gulden.

It should be understood that the annexation of Galicia to the Habsburg monarchy brought recognizable changes to the lives of the Jews. During the year of the annexation, there were 4,839 residents in Zolkiew, which included 2027 Jews. The Austrians arranged that there would be organized administrations in only a small number of cities in Galicia – Brody, Lvov, Sambor, Drohowycz, Stary, Resza and Jaroslaw. In contrast, for the remaining cities such as Halicz and Szniyatini, there were illiterate people in charge, and only the secretary of the town was a Jewish man who could read and write. The condition in Zolkiew was not any better.

The city nobility maintained an adverse relationship toward the Jews. Despite the difficult economic circumstances of the Jews, the Polish aristocrats argued that things were good because the Austrian authorities were taking measures to improve and make their situation better.

Contrary to this stance, it is necessary to stress that the Austrian administration literally took drastic measures in their desire to change the status of the Jews in one act, and to accustom them to the new circumstances in their lives. The land and the Jews in particular, were blanketed with a wave of orders, reforms and decrees that did nothing but create chaos. However after a few years had passed, the Austrian bureaucratic apparatus in Vienna, Lvov and in the provinces of Galicia, began to grasp the situation, and understood that change of this sort could not be achieved through reforms directed toward the Jews, or by issuing decrees while ‘standing on one foot,’ and employing harmful and fanatical methods.

The fate of Zolkiew was similar to the fate of all Jewish communities in Galicia.

On December 6, 1772, the first patent of the authorities that dealt with the issue of the Jews was implemented to initiate a census of the Jews. The Rabbis and community Heads were asked to provide an exact description of the situation of the Jews in their communities, how they were managed, reforms, and the status of family assets, business activities, etc.

The Zolkiew community was unable to adjust to these new conditions, and as was done in the days of Polish rule, a request was submitted to Vienna in 1773 to permit it to enjoy its existing privileges that were granted by King Sobieski III and various other city rulers. The community did not receive an answer, but it did not give up on its demands. Punitive taxes and residential requirements were deliberately designed and levied on the Jews of Zolkiew in 1779, which stood in contrast to earlier privileges granted to the community. R' Avraham Pesach stood against this in the name of the community, and asked of the leaders of the Guberniya for help from the government. The Guberniya leaders responded that an obligation of this kind must first be submitted to lower level offices, and not directly to the Guberniya leaders.

[Page 76]

On November 29 1782, Vienna announced to the Guberniya community leaders via a special decree, that there was no reason to reconsider the previous rulings nor relax them, even in the future, in order to cope with the existing situations and the request to grant the former privileges because of the need for work. Those privileges touched on municipal issues and on agreements between city rulers and the Jews of the city. R' Abraham Pesach did not stand in conflict with the orders of the government.

The economic condition of the Jewish community continued to deteriorate in the face of limitations on the production of beverages, and the rules for quality control. The Jews requested that the taxes of 1772-1773 be nullified in view of their increasingly difficult economic circumstances, and the economic destruction that touched them in the trail of the many invasions that preceded the division of Poland. The authorities opposed these requests, and instead sought to raise taxes in the strictest manner allowed by law. After many efforts, there was relief granted for taxes and payments to the municipality in 1775, which alleviated some responsibility of monies paid by the poor and stricken. The lightening of these burdens aroused the jealousy of the Christian citizenry, and caused no small rise in the tension among the local relationships.

During the Polish period, the Jews paid 30 Kreuzer as a head tax.

During the first period of taxation after the Austrian annexation, the head tax in 1774 was raised to one Florin and was also applied to children over the age of one year. In total, the Jews of Galicia paid 41,178 Florins.

In place of the head tax, a tolerance tax[1], the Toleranzgebuehr, one Florin per capita, was imposed in 1776. Added to this at the same time was an entry tax, and a merchandise tax which was levied on an individual basis according to whatever was imported. The allocation of the taxes among the communities was proposed by the Jewish leadership, the Juden-Direktzion, and the amount of tax that had to be paid by itinerant vendors was levied by the communities themselves.

In addition to all of these payments, the Jews were required to pay a wedding tax and a degree conferment tax. It was understood that all of the community taxes – the ‘korovka’ etc., remained in place. However, these were placed under the oversight of the government which used them to defray the debts of the communities. According to the decree of August 10, 1792, by the office of the courtyard, the Jews had to pay a general tax, a tax for the army officers, property tax (rustikal-schteier), a house tax, a necessity tax, and an entry tax. The burden of taxation weighed heavily on the Jews of Galicia. This compelled the government of Austria to propose reforms in 1784 on the entire tax structure of the Jews. It also resulted in Jewish involvement in embezzlement and the paying bribes by some communities in order to avoid the increase in taxes. The allocation of taxes by the chief Jewish leadership was a form of Jewish management, and was seen as an injustice. If one community lacked the force of implementation to pay off taxes, as was the case with Lvov in 1783, this sum was then distributed among the remaining communities of the province.

[Page 77]

After the implementation of the reforms of 1789, the Jews were required to pay a tolerance tax of 4 Gulden for every head of a family, a house and property tax of 1 Gulden for each family, a kosher meat tax, depending on the type of meat, a wedding tax, a synagogue construction tax, and a new cemetery tax, altogether 100 Gulden per year, and a tax for prayer quorums of 50 Gulden a year.

The tolerance tax was canceled in 1797, as was the house tax and property tax. In its place, a candle tax[2] was created. The levy was 2 Kreuzer for every candle used for the Sabbath and Festivals, 6 Kreuzer for Yahrzeit candles, a half a Kreuzer for Hanukkah candles, and 10 Kreuzer for candles for Yom Kippur.

Because of the burden of taxation, the communities were left owing the government large sums of money to defray taxes.

The government ruled in 1780 that it would foreclose on Jewish earnings because they were unable to pay the taxes. The Zolkiew community turned to the government with a request to cancel this foreclosure order, and to take into account the condition of the Jews who did not have the means to pay these high taxes. The authorities in Vienna ordered an analysis of the situation in July 1784, and decided to defer the foreclosure of tax to the government. Based on the complaints of the community toward the increased taxes on assets, and the findings of the analysis, it became clear that there was a need to align the taxes with the ability to pay. The matter stretched out to August 1784, and in the end, the level of taxation was decreased.

In 1790, a separate tolerance tax was levied on the Jewish families in the Zolkiew area in the amount of 12,260 Florin. A new administrative tax (rezhi-beitrag) of 3,065 Florin was added for a total of 15,325 Florin. These taxes were levied from 1788-1789 counting as a tolerance tax – 3,615 Florin, 44 Kreuzer, administrative costs of 903 Florin. In sum these taxes in 1790 came to 4,409 Florin, 44 Kreuzer, and in addition to residual or unpaid taxes the Jews owed 8,334 Florin, 30 Kreuzer. In other words, they had paid almost half. It is important to stress that every figure in the payment of taxes caused the typical Jewish citizen to become a ‘known pauper,’ lacking the funds for sustenance and for making a living, and the likelihood of being expelled from Galicia.

It is therefore no surprise that the authorities in Lvov and Vienna were inundated endlessly with requests to defer payment of taxes. There were complaints about the size of the large sums that were beyond the capacity of the communities in the area to liquidate.

This outlook persisted for many years. It became clear, especially in 1811, when the extent of the treasury reforms on the classification of the populace were assessed, that these reforms increased the burden of taxes. This condition even sparked a reaction by the Galician Guberyanim[3] in Lvov. It did not stint on emphasizing in its special report conveyed on July 12, 1811, that the taxes levied on the Jews were more exaggerated (ubergespannt) than needed.

[Page 78]

The central business of the Zolkiew Jews in the second half of the 18th century was running distilleries for beer and other beverages that were owned by the city, and the distribution of beverages, and running saloon franchises. At the beginning of the Austrian Occupation the Jews faced many difficulties in this area. However, in 1775, a change was made for the better, and the Jews of the city received leases for all their beverages, in the place of two years of pay.

During these years (1775-1780) known lessors were Joseph Khatuk and his partners, Asher, Leib Jampolsky, Meir, Isaac, Mordechai and Joseph Dreizin. They leased the ‘arenda[4]’ of beer, mead, whiskey, mills and distilleries of the city, producing from 3,000 to 24,000 Gulden of income per year. The wine merchants made contracts on February 22, 1781 with the ruler of the city, Karol Radziwill, in which they assumed the obligation to pay the going price demanded by his businesses. In addition to the wine merchants who signed up for this, there were also signatures by Shmuel Markowitz, Jonah ben Eliyahu and David ben Avraham-Shmuel Markowitz, the distributors – Moshe ben Leib, Baruch ben Eliyahu, Israel ben Yaakov, Moshe ben Nachman, and the heads of the communities - Leib ben Moshe, Avraham ben Meir, Yaakov ben Nahum, Yekhezkiel ben Yaakov, Joseph be Leib, Yaakov ben Berisz and Joseph ben David.

These lessors especially kept watch over the continuation of their privileges, and assured that beverages would not come from outside of the city. To accomplish this, the officers of the distributors turned to ben Moshe, Baruch Mattis, Yaakov Barlim, Berisz Joseph Deizer, Joseph Meir and Yitzhak Jackobovitz, and Shmuel ben Moshe, and the saloon keepers, to the rulers of the city with a request, to permit them to bring whiskey from other cities, something that would certainly not cause any harm to the courtyard treasury. The owners of whiskey distilleries opposed this group of distributors. Shmuel Baruch and Isaac Yaakov, made a complaint in February 1784, that they had enjoyed their privilege for many years for the distribution of drink, without limits. Christian and Jewish distributors joined together in this economic struggle. On March 3,1784 they turned to the district authority in Zolkiew and begged for its intervention in order to protect their franchises. The central authority turned this entire issue over to the Guberyanim. The issue of the Jewish distilleries was presented by Israel Nathan and David Avraham, and that of the distributors, Avraham Meir and Joseph Leib.

The authorities forbade the owners of the whiskey and beer distilleries and lessors of the beer distilleries to distribute drinks in their distilleries, but it was permitted for them to sell their products in liquor stores for this purpose.

This struggle was conducted not only in Zolkiew but almost in every city where there were distilleries that produced beverages. These arguments gave rise in May 1789, to exclude the Jews from leasing distilleries and distribution in cities and towns, especially for those who prepared beverages in their homes. As it was, this led to the cessation of the ability for Jews to distribute beverages in all of Galicia, which further deteriorated their economic status.

The authorities observed the beverage distribution process was the principal cause for the delay in the improvement of the condition of the farmers. It was understood that this national policy struck hard at the economic status of Zolkiew's Jews. Despite this, the policy of the government was not pulled back. For example, when the provincial office was asked, in 1789, if it was permissible for Jews to participate in the leasing of the city's resources, Vienna responded that ‘it is permissible for Jews to lease the municipal propagation on condition that it be connected with a tavern.’

[Page 79]

This restriction closed down a recognizable number of Jewish distributors in Galicia, mostly in Zolkiew, nevertheless, in the course of the years, the Jews returned to leasing and distribution. In 1827 there were five mead distributors, four malt merchants and eight distributors of guarded beverages. By the second half of the 18th century, in Zolkiew alone, there were more than one hundred taverns.

Organizational change was enabled by the reforms of the Empress Maria-Theresa from the year 1776. The Jews of Galicia were organized in one separate body headed by the Chief Heads of Jewish Galicia (general-direktion) based on an hierarchical ladder, composed of from 6 to 12 Parnassim at the start. All communities in one province – in all of Galicia there were 6 provinces that had provincial officers at their head – stood under the leadership of the Parnassim of the province and on top of them 6 Country Parnassim (landes-eltesteh) were added.

The 6 Provincial Parnassim and 6 Parnassim of the country with the Chief Rabbi at their head, represented the primary management body of the Jews in Galicia (general Juden direktion). An order received from Vienna on August 14, 1775 stated that in the future, the Jews were required to obtain special permission for the selection of the heads of the communities from the provincial office. However, this had to be preceded by the payment of taxes.

The administrative separation of 6 provinces was annulled on March 27,1782, and 18 provinces were put in their place. Zolkiew and 15 of the surrounding cities were designated as an independent province.

The organization of the communities was annulled in 1785, in accordance with the order of 1776. There were no national community organizations designated to take its place. According to this new reform, only the local Parnassim remained in place, except for the Parnassim of Lvov and Brody, led by 7 Parnassim, and for the rest of the communities, including Zolkiew, led by 3 Parnassim. These Parnassim were responsible to represent their communities before the authorities. They were to be concerned with the welfare of the poor, working with the Rabbi on matters of births, deaths, marriages and inheritance, the responsibility of levying taxes on the community and on the Jews, and to manage all of the affairs of the community. The Parnassim were dependent on the provincial authorities, who saw them as being submissive nonetheless.

Aside from the heads of the community there were other positions that required selection, such as Gabbaim for the synagogue, charity collectors, hospital visitors, assessors and bookkeepers. There was a full array of appointees consisting of the Rabbi, Dayanim, Ritual Slaughterers, Shamashim and grave diggers. Office matters were handled by the secretary of the community. The privilege of selection was given to the heads of families that prepaid one year's worth of taxes in the form of the cost for 7 candles. The privilege of voting was tied to the payment of a candle tax for 10 candles and knowledge of reading and writing in German.

The Parnassim who stood at the head of the community from 1781-1785 were: Leib ben Moshe, Avraham ben Meir, Yekl ben Nahum, Yekhezkiel be, Yaakov, Joseph ben Aryeh, Yaakov ben Dov and Joseph ben David.

The known community heads from 1785-1800 were: Avraham Yehuda Leib Meyerhoffer the owner of the printing house, Sh. Epstein, Mordechai Rubinstein, N. Eckstein, Sh. Haberman, Y. Kraus, M. Bandar, Y. Fessel (Pessel?), and Shmuel Nachtman.

[Page 80]

Avraham Yehuda Leib Meyerhoffer, N. Bernstein, and Chaim Margaliot were members of the Jewish emissaries of Galicia. They approached the Royal Military Advisory Council (hauf kriegs-rat) in Vienna in 1788, with a request to release Jews from military service by paying a compensation, or at the least to assign the Jews to military transportation. The reply from Vienna was that this matter had not been discussed. In September 1788, the authorities issued orders to cease the removal of the Jews to a greater distance outside the community centers of business, under the conditions that they would limit their merchandise to the houses and fields, and they were forbidden from dealing in leases. These orders were in connection with the decree to marginalize the presences of Jewish beverage distributors, granting them permission only to permit them to remain in the villages to service the villages with fields, build houses, and manage an agricultural business.

With regard to the request by the emissaries to release Jews from military service, Nachman Dessauer proposed that whomever had once been a teacher of Hertz Hamburg, be released from service. In March 1790, there was an appeal to the government, to discipline the emissaries of the Jews in Galicia, Bohemia, Moravia, and Hungary, who were pushing to not draft Jews new to the community, for service mandated by the authorities in Vienna.

During these years, the assets of Radziwill deteriorated, and parts of the city were sold off to common folk. One part passed into the hands of the Austrian government. In the presence of these circumstances, in 1781, the Jews of Zolkiew notified Radziwill of their willingness to continue to pay the ‘korovka,’ leasing monies, and the monies due for drinks and beer, and also to cover all of the debt that was put onto the millers, butchers, and the merchants of grits. This declaration was signed by the heads of the community R' Leib ben Moshe, R' Avraham ben Meir, R' Yekl ben Nahum, R' Joseph ben Aryeh, R' Yaakov ben David, R' Yekhezkiel ben Yaakov, and by the officers involved in the sale of wine and distribution of beverages, and the butchers.

A difficult period full of mistakes, arrests, and the hardship of assuming financial burdens came on to the Jews of Zolkiew.

In 1784, a dispute broke out between the community and the government over the basis for the ‘korovka.’ The community recorded the leasing income as ‘kov uvaka’ without obtaining permission from the provincial office. The authorities blamed the heads of the community for ‘abusing’ the funds of the korovka that were set aside to defray the debts of the community. When the matter was aired before Kalmans, the commissar, the situation moved the Parnes R' Shmuel ben Yaakov to say sharp words. The authorities punished him with a jail sentence of 8 days, two of which he had to subsist on bread and water. R' Shlomo Meir, the cashier of the community, was pushed out of his position and ordered to appoint a different cashier. The community was ordered not to defray funds of the korovka to creditors in monasteries, and churches, rather to the government treasury that would create a separate facility to defray the debts of the communities.

The community nevertheless stood its ground and asked for a separate body to support it. All of the korovka funds were appropriated, but despite the efforts by the community, a positive conclusion was not reached. Quite the opposite. The provincial office was authorized to conduct a thorough audit of all community issues, especially those regarding the leasing tax on kosher meat, the korovka, and in addition to this, to provide a detailed list of the ‘impoverished Jews,’ that were to be thrown out of the city.

In January 1785, Vienna deferred all the complaints of the community.

In the meantime, a new issue arose, this time from the Zolkiew Jews who assumed R' Leib'l Herschel Horodniker had the power to submit a complaint on their behalf. Their position was that in 1780 the community turned over a small coverage, more than the significant amount of head tax paid by the Heads of families, and that with regard to the korovka funds set aside for liquidation of community debt, the community, by its own initiative, took out 2,685 Florin 45 Kreuzer to cover debt figures in taxes for other expenses of the community.

[Page 81]

On September 12, 1785 the authorities gave an order to analyze the facts of the complaints and to punish the guilty community heads with a fine of 50 Ducats. The community was completely angered by Leib'l, and turned to the provincial office with a request to drive him from the city, since he incited arguments and discussions among the members of the community.

The authorities opposed the fulfillment of the community's request, using the excuse that Leib'l Herschel was a ‘known individual’ and quite the opposite, a very explicit order was given, that he was not to be given any punishment, and there was reason enough for him to keep his position in Zolkiew.

In addition to the heavy taxes levied upon them, there were all manner of prohibitions placed upon the Jews. The most onerous was the tax on marriage. The sponsors of the event had to pay from 3 to 30 Ducats for the marriage of their sons, and whoever married off a child without the permission of the authorities could anticipate the confiscation of all his assets. Even participation in a wedding not granted permission could bring on a heavy fine.

|

|

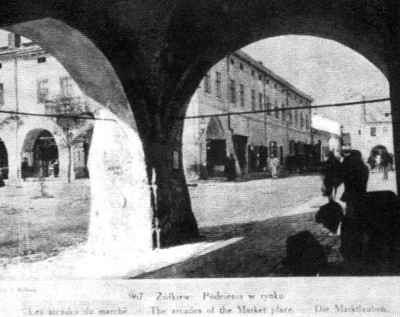

| Passageways near the ‘Square’ (Rynek) with the arcades |

|

|

| A part of the ‘Square’ (Rynek) with churches |

[Page 82]

In accordance with the new reform implemented by Kaiser Joseph II on May 27, 1785, the remains of community autonomy were nullified and all its national and juridical permissions were canceled. The taxes were not levied on the community as a collective body, but rather on each Jewish person individually, and the assessments were turned over to national representatives. The independence of community leaders was removed, and they became a religious body only. When the Rabbinical courts were nullified in April 1794, all of the communities became equivalent and judged to exist under the rule of national courts and in police matters – under the sole authority of the municipality.

According to the decree of August 28, 1787, family ledgers were created, and from 1789 on, the Jews of Galicia were required to adopt German family names. This was presumed to be pressure to bring about the ‘Germanization’ among the Jews. Because of this move, the communities and rabbis were required to conduct their affairs, keep their books, and list only in the German language.

As far back as 1776, merchants were required to keep books of merchandise with copies, financial books, and lists of the merchandise and storage facilities, but not everyone had the right to keep them in his own language. In accordance with the reform of May 27, 1785, Jewish merchants were required to keep their books in German or in the local Polish language. Insofar as letters written in correspondence with the government or in general, they were forbidden to utilize either Hebrew or Yiddish. Only German was allowed.

A more difficult issue at hand was the question of the military draft. The government issued an order on March 18, 1788 which required Jewish people to be drafted along with the rest of the populace. However, by 1790 there was an easement through which Jews were freed from military registration and were given permission to defray their service by providing a contribution of 30 Florin per individual. This condition continued until 1804.

The responsibility of being drafted was placed upon the Jews of Galicia similar to that of the Christian population in 1804, and they were drafted from all of the provinces. This nullified the monetary payment that had previously freed them from military service. The practice of assigning Jewish draftees to the transport service was also revoked at this time. Conditions were set up to free individuals from military service for special circumstances, such as the privilege of citizenship, permits to practice a craft, or a merchant possessing a permit.

One of the basic reforms demanded by Kaiser Joseph II of the Jews of Galicia, was to assign and move a portion of the Jews to agriculture. From 1771 onwards, the Viennese authorities had already discussed the need to transfer a significant number of Jews in Galicia to areas in the provinces to carry out agricultural work. The Kaiser, who conveyed his own favorable outlook on physical activity, intended to disperse those Jews who had lost their ability to make a living before the prohibition against beverage distribution, and to get them involved in agriculture. In order to attract them to agriculture, he decided to reduce the tolerance tax by fifty percent for Jewish agricultural workers, and afterwards, canceled this tax entirely.

In August 1785, when thousands of Jewish families were left without income as a result of the reforms against the Jews, the Kaiser decreed an agricultural initiative for the Jews. The text of the decree indicated a requirement to re-settle 1,400 Jewish families from all over Galicia. The Zolkiew community was responsible for accepting 11 families, and the entire Zolkiew province was required to take in 75 families. The communities of Zolkiew, as was the case

[Page 83]

for other communities in the province, succeeded by 1792, to fulfill the burden put upon them. In a special notice, the Guberyanim notified Vienna that the Jews of that province had satisfied the demands of the order.

In July 1792, Vienna gave an order to the Guberyanim to praise the authority of the Zolkiew province which had satisfied the order to resettle the Jews for agricultural work. The Viennese authorities conveyed their satisfaction that the quota had been filled, and gave an order to praise the Stary province offices as well as those of Sambor, Zalszcziki and Czernowitz.

In the Zolkiew province, 75 Jewish families settled on 63 parcels of land. This included 113 men, 120 women, along with 62 young men and 75 young women under the age of 18. The settlers received 75 homes, 75 stables and granaries, 75 agricultural tools, 144 horses, 162 oxen, and 248 cows. In the Zolkiew community itself, 11 families settled on 11 parcels of land. There were 16 men, 29 women, along with 4 young men and 9 young women under the age of 18. The settlers received 11 houses, 11 stables and granaries, 11 agricultural tools, 29 horses, 19 oxen and 49 cows.

After these arrangements, the implementer in the government advisory council in Vienna, the leader Furstenbusch, confirmed at a meeting of the government council (stadt-rat), that the office in Zolkiew was singularly outstanding.

The numbers of settlers in other provinces were: Kulikovo - 15 families, Magierow - 4, Rawa - 8, Nemirov - 3, Mosty' - 2, Kristinopol - 5, Sokal - 8, Tartakov - 4, Varenz - 4, Belz - 4, Ohniov - 3, Ulszica - 5, Luvcow - 3, Ciesanow - 3, and Lidskow - 3.

The budget needed to cover the costs of settlement was levied against the communities in the areas of settlement. The costs for the settlement of each family were estimated to be about 250 Gulden. Each of the heads of families were required to settle one needy family.

In 1822, there were only 10 families remaining in the Zolkiew province that were settled at the expense of the communities, but not one at the cost of the province itself.

There were administrative changes made in Galicia in 1785. The country divided the land into 18 provinces. Among them, Zolkiew was designated as the most wealthy among the provinces. Aside from Zolkiew itself, an additional 15 towns and settlements in which a number of Jews resided, were attached to it. There were 6 settlements added, and to the rest of the 15 towns – 67 settlements, and especially, 73 Jewish settlements were attached to Zolkiew.

In accordance with the Jewish reform that began in July 1785, a rabbi of the valley was put into place (Kreis Rabbiner), and for the remaining positions, religious directors (religezens-weiser) or cantors were (schulzinger) appointed. The rabbis were selected as community heads for three years, not as community heads by the community that were balebatim on their own, but rather by all the Jews of the province. The first Rabbi of the province in Zolkiew was R' Moshe Zvi Maiseles.

[Page 84]

Among the duties of the provincial Rabbi were to rule on matters of the faith, to manage the book of births, weddings, and deaths in the German language, to oversee the clergy, cantors, shamashim, to proclaim an embargo only in accordance with the direction of the authorities, and to swear in people regarding political issues in the synagogue. The proclamation of any added embargoes was strictly forbidden, and doing so was severely punishable.

The Rabbi of the Zolkiew province, who was also the Rabbi of the Zolkiew community, received a stipend of 400 Florin and an additional amount of 150 Gulden. There was a religious director appointed to assist him, and he received an annual wage of 208 Florin, and an extra stipend for each lecture given. In addition to his pay, the Rabbi received compensation for different services and also for registering births, weddings and deaths in the amount of 7 ½, 15 and 30 Kreuzer, and similar compensation for the Hazzanim. The Rabbi was exempt from community taxes, but in the instance where his wife or close relatives run a business, he had to pay the usual taxes associated with such businesses. According to the law, it was forbidden for the Rabbi to demand gifts of special payment for arranging either marriages or divorces.

The annual pay for a religious director in the remain communities of the Zolkiew province was: Belz – 170 Florin, Cieszanow – 150 Florin, Kristianopol – 176 Florin, Kulikovo – 160 Florin, Magierow – 195 Florin, 24 Kreuzer, Mosty' Wielkowo – 148 Florin, Nemirov – 104 Florin, Uszlica - 148 Florin, Rawa – in Tartakov – 40 Florin, a residence in Sokal – 170 Florin, Uhniv – 129 Florin, and in Varenzh – 57 Florin.

A census was taken in Galicia in 1788, but our information includes only the number of Jews in full provinces. In the Zolkiew province with 16 communities, 3,377 Jewish families were counted which included 16,157 souls. The Jews paid taxes as follows: Level A 1,662; Level B 124; Level C 65. There were 1,516 families that were designated as poor.

In 1792 there were 3,963 Jewish families with 14,144 souls (6,785 men and 7359 women), and they paid taxes as follows: Level A - 1198 families, Level B - 275 families, Level C - 118 families, with 1,472 families designated as poor.

In the details of these census records mentioned above, the type of professions and work in which people were engaged, is missing. From a variety of government sources we learned that the Jews of Zolkiew were involved in the sale of various goods in addition to their occupation as beverage distributors. Apart from a limited number of merchants and wholesalers, most were retailers, traders, intermediaries and the like. Fortunate Jews succeeded in getting a franchise to supply the military, such as Yitzhak Ehrlicher who in 1791 received a franchise from the authorities to supply food for the entire province of Zolkiew.

There was a recognizable number of craftsmen, mostly tailors, furriers, padding makers, woodcutters, binders, etchers and book binders. There were a few who printed books in Zolkiew. Agricultural work was done in the outskirts of the city, which involved growing vegetables, running stables and raising fowl.

There were a limited number of wholesale merchants in Zolkiew who had control over the sale of wood, and the weaving of flax, which was exported to Danzig.

|

|

| The Shammes leaving the Great Synagogue |

[Page 85]

In 1775, the conditions of the merchants and wholesalers in Zolkiew, which in those years was a center of commerce, flax production and exports to Danzig, became more difficult. This was in the aftermath of the setting of the high tax levies in Poland and Prussia for merchandise coming from Galicia, which caused merchandise to become more expensive. Efforts were made to take diplomatic steps, and on the basis of these appeals, the authorities in Poland and Prussia promised relief.

The Town and the community tried to have the transfer tax removed from Zolkiew during the years 1798-1794, justifying the reasoning with the argument that this tax was destroying the economic life of the city residents. The authorities did not move from their position, and it was then that R' Shmuel Nachtman was chosen to represent all of the citizenry before Kaiser Franz Joseph I. On August 1, 1798 Nachtman appealed to the Kaiser, but his efforts were in vain. However the Kaiser passed on the request to the Guberyanim in Lvov, and it was this body that turned down the request.

Before the reforms of Kaiser Joseph II from 1789-1794, each community, even a small town, was responsible to maintain an elementary school; in larger communities, a normal school and in Lvov and Brody, senior level schools, following the example of the general school system. German was the language of instruction in all the schools. The official name of these schools was ‘Deutsche-Judische Schulen’ or ‘Yiddish-Deutsche Schulen.’ Up to 1792, schools were established only for boys. The lower schools consisted of only one class. Normal schools had three classes with 2 teachers and a principal (Uber-Lehrer), general schools were complete in size, that is to say, 4 classes with a larger number of teachers.

This decree forbade Jewish boys from the study of Gemara before they finished elementary school. The elementary schools were established at the expense of the Jews, but were under the oversight of the government, not the communities. Hertz Homburg was appointed as the head overseer for all the Jewish schools in Galicia. He had taught the sons of Moshe Mendelson. Most of the original teachers who were invited to teach came from among the Enlightened German speakers of Moravia and Bohemia. A teachers' seminary was established in Lvov to prepare the Jewish teachers. The first school in Zolkiew was founded in 1785, and the teacher was Nachman Dessauer.

As you can understand, the Haredim[5] opposed the establishment of the school and refused to send their children there. The teacher, Dessauer, young, but imbued to be the ‘kultur-treger’ to spread Enlightenment among the Jews of Zolkiew, did not understand the spirit of the Haredim. His position and his behavior stood decidedly in opposition to the spirit of the Jewish populace. The authorities saw a need to move him from Zolkiew to Lvov, as it said in all reports, ‘because of his behavior that merited discipline.’ As to the details of his behavior that merited discipline, and the real reasons for his transfer, the record is silent, and in his place, the teacher Yitzhak Avraham Griderbaum was appointed. The salary of a teacher in Zolkiew was 200 Florin annually. In the rest of the Zolkiew province there were schools in Kulikovo, Rawa, Kristinopol and Belz.

[Page 86]

The annual salary of a teacher in Kulikovo and Belz was 150 Florin, in Rawa and Kristianopol the salary was 200 Florin. Due to the lack of teachers, there weren't any schools in the rest of the communities.

From the outset, the teacher Griderbaum showed greater patience with the Haredim. In 1787, members of the ‘Committee overseeing the Eastern Galician schools’ visited the school during a testing period. In the report summarizing their visit, the committee members said that it was clear to them that based on student answers, the teacher, Griderbaum, fully exerted himself to see that the children succeeded in their studies. This led to an increase of his salary to 150 Florin in contrast to the salary of the teacher in Zolkiew that was set at 200 Florin. On February 4, 1788, Griderbaum asked the overseer of the Jewish schools, Hertz Homburg, to increase his salary, indicating that thanks to his efforts and diligence the students were advancing well.

It appears that his request was responded to positively, because in the listing of pay to teachers in the year 1789 the salary of Griderbaum is shown as 200 Florin.

Griderbaum did not remain in Zolkiew for many years. Those who were very pious, and the secretary of the community, undermined his position, and he asked to be transferred elsewhere.

In 1790, Avraham Bitschoff served as the teacher at a salary of 200 Gulden. Even this teacher had a brief, one-year tenure, as a result of the struggle with the very pious who refused to let their children attend the school. The heads of the community were especially among those who fought fanatically against the school and its teacher. They periodically turned to the provincial office with complaints and accusations, saying that the teacher disciplined the children and that this discouraged them from learning. The parents felt that this bitterness and anger was justified. According to Bitschoff, the heads of the community refused to let the children attend this school.

[Page 87]

|

|

| The headstone on the grave of Alexander Schur, author of ‘Terumat Schur’ in the Zolkiew Cemetery |

|

|

|||

(from the 17th Century) |

[Page 88]

In 1793, the government levied a tax on the heads of the communities in the amount of 50 Florin. An exchange of letters took place between the offices until they achieved the order to cancel the levy in January 1797.

After Bitschoff became the teacher, Meizel, and the very observant heads of the communities, presented all sorts of accusations in connection with his behavior towards the pupils.

Despite these complaints by the leaders of the community, which during that period was in the hands of those opposed to the school, Meizel retained his position. He expanded the school and a second teacher, Avraham Rosenberg, was hired. Avraham's teaching methods were well received, and in 1797, he was granted a raise of 6 ducats to his yearly salary which rose to 150 Florin. This money came from the funds of the Jewish school.

Meizel and Rosenberg remained in Zolkiew until 1806, at which point the network of Jewish schools in Galicia was abolished. From 1785-1806, those serving as teachers in the Zolkiew province were Aharon Lehrer in Kulikovo, Lejzor Heller in Rawa, Lev Tur in Kristianopol, Eliezer Reiss in Belz, and Shimon Skucz in Sokal. Shimon was transferred to Lvov in 1805. There were no Jewish schools in the remainder of the towns.

In addition to paying teacher salaries, Zolkiew was taxed for the salary of the Beller (clerk) of the province for handling the matters of the Jews, 350 Florin per year, and 200 Florin for the clerk's assistant. In the years 1782-1796, Avraham Kiarfowic served as the Beller as did his assistant, Hirshberg.

One hundred Jewish children attended the Jewish school in 1806, the year in which it closed. This was the smallest number in the entire province of Eastern Galicia. By 1817, only 2 Jewish students in the entire province of Zolkiew studied at the secular school.

The Jews of Zolkiew entered the 19th century under difficult economic conditions. From year to year the government increased the tuition for the Jews. Landowners who leased saloons to the Jews were allowed to charge what they wanted. The burden of taxation grew to the point that in the years 1808-1811, taxes were imposed on more and more aspects of life, including taxes on meat and Sabbath-candles. These taxes were added to the debt levied on the Jews by the authorities.

The authorities limited the number of Jewish beverage distributors and canceled most of their entitlements. Jewish saloon keepers were pressed into severe competition with the Christian saloon keepers, a struggle that continued until the end of the 1840's.

A census taken in the city of Zolkiew in 1812 revealed that there were 428 Jewish families. Eight-hundred-seventy-four men, and 925 women for a total of 1799 people. There were 2,714 Jewish families in the entire province, consisting of 11,069 people (5441 men, 5628 women), which was a very noticeable decrease when compared to the years 1788-1792 when there were 3,063 Jewish families.

[Page 89]

A census was carried out in the entire province in 1819. There were 2,332 Jewish families. Seventy-five Jewish families were engaged in farming for a total of 2,407 families. In comparison to the census of 1819 it is noteworthy that the number of Jewish families decreased by 207 during these years. In 1821 there were 10,740 Jews in the province compared with 197,058 Christians, a decrease of 3,321 people compared with 1812.

There were 11,517 Jews and 206,624 Christians recorded in the census of 1826. This was an increase of 769 people compared to the year 1821. Even with what is revealed in the numbers available to us with the force of significant curtailment with regard to the business of the Jews 1820's, there still was growth in the Jewish population.

There were 9 Jewish wholesalers who owned merchandising businesses with rights to sell throughout the Zolkiew province. Of the 30 saloons (hefene schenker) in all of Galicia, there were 8 in Zolkiew. Of the 24 fruit sellers in all of Galicia, 4 were in Zolkiew. Out of 18 bookbinders in Galicia, 4 were in Zolkiew. There were 16 mead sellers in Galicia, 4 were in Zolkiew. Out of 10 processors of grits, 5 were in Zolkiew, and there were 16 booksellers in Galicia, with 4 in Zolkiew.

There were 7 specialist craftsmen in Zolkiew in 1820. Out of 22 confectionery bakers in all of Galicia, there were 4 in Zolkiew. There was one single movie studio in Galicia, and it was in Zolkiew.

There were 236 Jewish tailors, furriers, sheriffs and shoemakers in the Zolkiew province. Of the 2,015 whiskey distillers in all of Galicia, there were 338 in the Zolkiew province.

Apart from these occupations, the Jews engaged in the grain trade, in farming implements, food, cattle and horses.

The Jewish retailers, craftsmen, and jobbers fought hard to maintain their existence.

The government raised the level of taxes significantly during the years 1819-1820. The Galician communities, including Zolkiew, turned to the authorities with requests to lower the taxes that had been levied upon them in the face of economic decline that offered no room for sustenance. They presented the fact that the collection of the meat tax and the candle tax made the tax load too heavy for the populace. Even the Guberyanim recognized the justification for the requests. They knew that the difficult economic circumstances and the struggle for existence that had been put on most of the Jews spoke to the need to lighten the tax load (ergenzung-schteier). The Guberyanim knew that there would be no improvements in the taxes, and was aware of the peculiar relationship between the demanded tax level and the income of those being taxed, and they stressed that there was a need to alter the relationship between the tax collectors and the masses.

In July 1823, the body of the Guberyanim proposed cancellation of the candle tax, the payment tax, and the special tax (extra-schteier). However, in Vienna, the law stood to maintain the tax on the Jews until the tax revision was reviewed, arguing that the Jewish tax collectors were at fault. The government proposed that the collection be turned over to local authorities, and the officials of the provinces were ordered to convey their thoughts on this.

[Page 90]

The officer of the Zolkiew province conveyed a negative reaction. This, however, was opposite the opinion of the officers of the provinces of Stary, Tarnopol, Stanislaw, Prszemsyl, and the Guberyanim in Lvov. Therefore, there were no changes in taxation.

There were actually no major changes in the lives of the Zolkiew community until 1848.

The Rabbis who served as leaders from the beginning of the Austrian occupation were: 1) Rabbi R' Moshe Zvi Hirsch ben R' Shimon Meiseles, who had previously been the Rabbi in Lancut, and was selected as Rabbi in 1757 after his father returned to his previous position in Cieszanow. Rabbi Meiseles was one of the Gaonim of his generation. He was invited to take the pulpit in Metz, and afterwards in Copenhagen, but he did not want to leave Zolkiew, where he served until his death on 18 Kislev 5561 (1803). His son, Avigdor was the Rabbi in Bilgoraj, and his daughter Freida was married to R' Avigdor, the Bet-Din Senior in Kamionka. He was the first Rabbi of the Valley in the Zolkiew province. 2) The Rabbi, R' Meshullam ben R' Mordechai Ze'ev Orenstein.

The family name of the father of Rabbi Mordechai Ze'ev was Lvov, and Yaakov took on the family name Orenstein. The family name, and that of the descendants of his father's brother, the uncle of Meshullam Zalman, was Ashkenazi. His father's family was from Zolkiew. The father of Rabbi Mordechai Ze'ev, the grandfather of R' Yaakov Meshullam, R' Moshe R' Yoss'keh's, was the son of R' Yoss'keh and the grandson of Hanoch Henykh. Hanoch was the son of Rabbi R' Joseph Yoss'keh, the Rabbi of Szydlow. R' Yoss'keh was a formidable scholar, a leader and a Parnes of the Zolkiew community, and a son-in-law of the tax collector, R' Bezalel. R' Moshe was born in Zolkiew and was among the wealthy and respected influential people, and a member of the community council. His wife Nechama (Ny'tcheh) was the daughter of R' Aryeh Leib, the Bet-Din Senior of Amsterdam, son-in-law of the Gaon, Zvi the Wise (Ashkenazi).

Rabbi Mordechai Ze'ev, the father of R' Yaakov Meshullam was one of the great Torah scholars of his generation. He served as the Rabbi in Satonow and Jampol (Podolia). His family remained in Zolkiew. He moved towards Hasidism while in Podolia, and as a result became known as ‘The Hasid who knew Kabbalah.’ When R' Aryeh Leib Bernstein of Brody was selected to be the country-level Rabbi of Galicia, in accordance with the orders of Maria Teresa (1776), Rabbi Mordechai Ze'ev was appointed to take his place. After the Rabbi of Lvov, R' Shlomo, author of the book, Mirkevet Mishna, made aliyah, Mordechai Ze'ev was selected as the Bet-Din Senior in Lvov and for the Valley.

The mother of R' Yaakov Meshullam was the daughter of R' Shaul the Acute, Bet-Din Senior in Olesko. He was born in 1773 in Jampol or in Satanow. He was still a child when his mother died. At the age of 12 he was married to the lady, Sarah, daughter of the Nagid[6] R' Zvi Hirsch Wohl of the Shaul Wohl family, and lived in his house in Jaroslaw. He attracted talented students and associates who came to hear his Torah. Among them were R' Eliezer Hurwicz, the Rabbi in Tarnogrod and author of the book, Noam Magidim, and R' Aharon Moshe Taubisch, the Rabbi in Szniatyn and afterwards in Jassy, and author of the books, Tosafot Re'Em and Karnei Re'Em.

Rabbi R' Zechariah Mendl Frankel served in Jaroslaw. He had two sons-in-law, R' Yehuda Leib Heller, and R' Naphtali Hertz ben Shaul the Acute, Bet-Din Senior in Olesko who was the brother of his mother, Freida. After his death, his son-in-law, Rabbi Yehuda Leib Heller claimed his right to the rabbinate. When he left his leadership position in 1800, the heads of the community invited the younger R' Yaakov Meshullam Orenstein, without considering the second son-in-law of Rabbi Frankel, R' Naphtali Hertz. This created a dispute in the congregation. While R' Naphtali was

[Page 91]

selected, he refused to accept the position. The members of the community leadership unanimously endorsed the appointment of R' Yaakov Meshullam Orenstein. His aunt, the mother of R' Naphtali conveyed her disapproval, intimating that Rabbi Orenstein arrogated the rabbinical chair that belonged to her son. When Rabbi Orenstin became aware of this, he immediately returned the rabbinical contract. He left Jaroslaw, and in 1805, moved to Zolkiew where he was selected to be the Rabbi of the city and the Valley after the death of Rabbi Moshe Zvi Hirsch Meiseles.

R' Yaakov Orenstein was not drawn to Hasidism like his father. Hasidism had spread in Galicia and created new centers in Belz and Sandzh, but Orenstein did not oppose it publicly. In opposition to this, he developed an aversion to the Enlightenment movement, which in his lifetime, had created centers of substance in Lvov, Brody, Tarnopol, Zolkiew and Tysmenytsia. It was R'Yaakov Orenstein who called the first embargo on the Enlightenment in Lvov in 1816. He stood at the head of the very pious in Galicia, and exchanged letters with the Gaon Khatam Sofer, in Pressburg, and his son-in-law, the Gaon R' Akiva Eiger, in Posen. He was an outstanding scholar, and compiled the book Yeshuot Yaakov. He died in Lvov on 25 Menachem-Av 5599 (1839).

3) After his death, no Rabbi was selected. The Dayan Yaakov Joseph Juzpa Segal Satran filled the position together with the Dayan R' Joseph Eliezer Gottleib.

4) In 1718 R' Yitzhak Shimshon Hurwicz Meiseles, the son of R' Avigdor Hurwicz the Bet-Din Senior of Kamionka was selected as Rabbi. He was the son-in-law of the Zolkiew Rabbi, R' Moshe Zvi Meiseles. His mother, Freida, was the daughter of R' Moshe Zvi Meiseles. He was born in Kamionka in 1789, and studied with Aviv, a noted teacher. In the years 1812-1816 he was the Rabbi in Monastyryska, and from 1816-1828 he was the Rabbi of Zolkiew. After this, he was selected to be the Rabbi in Czernowitz, and the country-Rabbi of Bukovina. In Czernowitz, he sat for the examinations of philosophy-pedagogy at the university, as was required by the Rabbis of the province, according to the rule of 1846. He received a special permit from King Ferdinand because he had not graduated from a gymnasium. In 1867 he left Czernowitz and returned to Zolkiew, where he occupied the Rabbinical seat for a second time after Rabbi Shmuel Walburg left Zolkiew, until he died on 25 Kislev 5639 (1879).

5) After Rabbi R' Yitzhak Shimshon Hurwicz-Meiseles went to Czernowitz, Rabbi R' Zvi Hirsch Khayot became the Rabbi.

In 1821 the matter of Jewish dress came up on the agenda. In paragraph 47 of the Josef decree, the Jews of Galicia, with the exception of the Rabbis, were asked to do away with their traditional garb which differentiated them from the rest of the population. However, in the face of opposition from the Jews, this demand was annulled.

When the central government in Vienna began to prepare a new Jewish code in 1816-1820, the question of traditional dress came up again. Was it desirable for the Jews to be forbidden to wear their traditional dress? Baron Hauer, the head of the Galician Gubernium, advocated to introduce a new prohibition, explicitly aimed at proscribing Jewish dress. He benefited from the support of many sectors of Enlightened Jews.

When the Jewish masses of the street learned of the efforts of the Gubernium to implement this proposal, a movement began to form an opposition. The community of Zolkiew also expressed its opposition. The heads of the communities and its provinces turned to the

[Page 92]

government with the request that Jewish dress be left to reflect economic needs. A change-over in dress would bring on new costs for the Jews, expenses that would have a notable impact on the tax revenues from meat. They argued that there would be a surplus of garments in the wholesalers' storage facilities and in retail stores that would go to waste, and that the costs required to pursue the German style of dress would become increasingly more expensive. The remaining communities of Galicia submitted similar positions, and it looked like a concerted effort coming from one place, as the various communities submitted their positions in the style that was included in the written request of Zolkiew.

The reply came from Vienna in April 1821, indicating that the positions taken by the Zolkiew community were not correct, since the change in Jewish clothing in Moravia proved that the costs for the new clothing did not diminish the income from the meat tax.

But the matter was not closed at that point. With efforts by the Galician communities, the merchants and furriers and even Christian owners of textile and silk factories within Austria, petitions were submitted in which these interested parties represented the severe damage that the change in dress would cause the designers and merchants, Jews and non-Jews alike. The end of the matter was that the proposal of the Galician Gubernium did not find an attentive ear in Vienna, which, for the time being, deferred this alleged solution to the problem.

During these years, Hasidism began to spread into most of the communities of Eastern Galicia. Before Hasidism succeeded in putting down roots, there were no signs of conflict between the religious Mitnagdim and the Hasidim in Zolkiew proper. Rabbi R' Moshe Zvi Hirsch Meiseles and his heir, Yaakov Meshullam ben R' Mordechai Ze'ev Orenstein, were in opposition to Hasidism, and under their influence, Zolkiew remained a community of the pious (Haredim). Also, the community leaders were in the camp of the Mitnagdim. However, in the small towns surrounding Zolkiew, the reach of Hasidism was stronger. There were conflicts and excommunications, especially against the young men who acted upon the yearnings of the Enlightenment, which succeeded in limiting the extent of its spread. Already, in the cities of Brody, Lvov, Zolkiew, Tarnopol, and Tysmenytsia, one would encounter not only outstanding religious sages, but also Enlightened people who understood their movement well, and had an analytic approach to history. There was a tendency toward the general Enlightenment in Zolkiew, and all of its external revelations. It was only a short time in which Zolkiew made efforts to resist the change in traditional Jewish garb and not to send their children to the school, despite the fact that according to the law, there was every opportunity to provide a general public education to Jewish children.

Zolkiew did not play a large part in the war to spread general culture that was being managed in these years in the communities of Brody, Lvov and Tarnopol.

Despite this, the limited number of the Enlightened, about whom a summary will be written in the coming chapter, gave a generously large donation to encourage the spread of the Enlightenment in Galicia.

Translator's footnotes

The candle tax was abolished in Galicia in 1848. Return

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Zhovkva, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 08 Aug 2024 by JH