|

|

[Page 17]

The Historical Background of Zborow

by Y.G. Labiner (New York)

Translated by Daniel Kochavi

Edited by Daniela Wellner

Zborow is an ancient city with a venerable historical past. It is not among the larger cities of eastern Galicia, however, due to its important strategic location, this town attracted every warring side and played a major role in the wars that took place in that area. Many big battles saturated its soil with human blood. Zborow is mentioned many more times than other much larger towns in that area which are much larger in area and population.

Thanks to Mr. Mendel Elkin, the librarian and director of the YIVO archives, a well known Jewish Institute, and to his assistant Mrs. Abramovitz, I discovered in the Institute's library, a hidden treasure of Jewish knowledge that includes facts about Zborow previously unknown to me and others in our home town. Interestingly, the name Zborow appears more often in Russian than in Yiddish, Polish or German. I drew most of the information of its past history from a 1910 Russian lexicon and from a book of historical facts published in Petersburg in 1880.

The time of the initial arrival of Jews in Zborow is not known. Mr. Gershon Bader, a Galician writer who lived in our town, stated that there is some evidence that at least one Jew or few more lived there 800 years ago. The Jewish population grew larger much later.

In (1648), a year of bloody decrees, a significant number of Jews lived in the town as described below. I was not able to research the period before T”H decrees. I was able to find facts recorded over the last 300 years starting with the T”H decrees. Little is known about the loss of Jewish lives and property inflicted by Bogdan Khmelnytski in Zborow. [Khmelnytski was a Ukrainian who led Cossacks and serfs in a rebellion against Poland-Lithuania. In 1648, it resulted in pogroms against Jews resulting in up to 20,000 deaths.] However, it is certain that he was in or near Zborow on his way from Ukraine to fight the siege in Lvov.

Khmelnytski, well known for his cruelty and blood thirst, was right up there with his 20th century heir. He and his hoard of Cossacks burned, looted, and murdered and did not spare any lives.

[Page 18]

Menashe Ben Israel in his well-known letter to Oliver Cromwell, the English ruler, stated that an estimated 180,000 Jews were murdered by Khmelnytski and his soldiers.

Khmelnytski's march through Zborow left bloody footprints. I can still remember the yearly memorial service for the T”H victims in our town when the El Maleh Rachamim [the prayer for the soul of someone who has died] was recited in their memory. Most likely they were Zborow Jews who were murdered by their oppressor.

The Zborow accord between Khmelnytski and Poland was signed on August 18 1649. Natan Nata Hannover, the T”H decree historian [early 1620s-1663], points out several items in this agreement, especially the one affecting the Jews. Khmelnytski demanded that the king declare that Zborow Jews were forbidden to reside where his 30,000 non-combatant Cossacks lived (who lived in that area). According to paragraph 7 of this accord, Jews were not allowed in except for commercial purposes. They were even forbidden to enter as tax collectors.

The original paragraph states in Polish: [text in Polish is translated for the reader and not reproduced]

Jews are allowed to come where The Cossacks live to conduct business only and only for a limited time.

The king and the cup-bearer who signed the accord were respectively Jan Casimir and Jan Radzhivill.

In 1651, the Cossacks and Tatars signed a peace agreement and on March 17, 1654 there was yet another peace agreement on the fate of the town.

It appears that the two sides were not able to reach a peace agreement. They swung between peace accord and cutting each other's throats. Obviously this unstable state of affairs aggravated the situation of the Jews who were caught between the anvil and the hammer.

On May 9, 1689, King Jan Sobieski's edict improved the Jews' situation in Zborow. This edict explicitly stated that the city mayors or the heads of the localities had to grant the same civil rights to Jews as given to the general population and ensure the same protection. To improve their economic situation, Jan Sobieski established four market days a year when Jews were entitled to freely sell goods. The decree to the mayors also stated that Jews were allowed to sell drinks, own taverns, and collect taxes. However, non-Jews who wanted to sell drinks were given preference.

Zborow Jews told stories passed on from previous generations that Turkish soldiers escaping from the Russia-Turkey war of 1768-74 passed through Zborow.

In 1795, Poland was divided among its three neighbors and Zborow, being part of Galicia, became part of Austria. Later in 1796, the first public school was opened in Zborow.

According to 1765 statistics, the size of the Jewish population in Zborow was 845. Another more reliable source shows that there were only 655 Jews that year. According to the 1900 census, there were 2,084 Jews in Zborow. The “Israelite calendar” published in Vienna in 1913-1914, indicates that 2,300 Jews were registered in the Jewish council of the Zborow and of them, 400 taxpayers.

[Page 19]

After WWI, Poland carried out a census. According to the official report, found in YIVO, 4,230 Jews lived in Zborow and neighboring areas, 2,045 men and 2,185 women.

The war resulted in a larger number of women. This census defined Jews as illiterate if they could not write or read Polish. There were 393 Jewish men and 493 Jewish women illiterate. These numbers are questionable since most of them could obviously pray and read Yiddish.

In 1931, 10 years later, another census showed that only 4,000 Jews lived in Zborow, probably due to emigration. Jews tried to escape to any place with open doors. Some moved to Eretz Yisroel with or without immigration certificates. The US gates remained open for a while but eventually closed up tightly. Jews from Zborow and other towns searched for countries open to immigration. Those included Canada, Cuba, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and other countries in central and South America. The main reason for emigration was the harsh economic conditions of Jews in the Polish Republic. The significant differences between the decrees of King Jan Sobieski and those of the government of new Poland such as Grabfski's, drove many Jews, especially youth, to leave. One can only wish that this number could have been larger.

Even if it is not an important historical date, it's worth mentioning the large Zborow fire of 1889. Most of the Jewish quarter was destroyed leaving the Jews completely destitute. The Zborow Jewish community was desperate, but slowly the Jews recovered, rebuilt their town anew and the economic situation returned eventually to its previous level.

Zborow underwent many political and economic upheavals, perhaps much more than it could stand. Under Austrian rule, the town was part of Eastern Galicia. During this period the political situation of Jews was reasonable, unlike their weak economic situation. Under Polish rule, Zborow was part of the so called “Malopolska,” little Poland. Both the political and economic state of affairs of the Jews was very sad.

At the start of WWII and after the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, the town was under Soviet Russia rule. Then and even now, it is part of Western Ukraine. During the short period of Russian occupation until the outbreak of the Russian-German war and the invasion of our town by the Germans, the state of Zborow Jews was undefined. Economically, the youth were able to find work with the new authorities. The older generation suffered greatly as is reflected in their letters.

Because of its strategic location, Zborow was an important target for the warring camps and was used as a ball in a ball game between them. Under Austrian rule, Zborow was near the Lemberg-Podwolochyska train line and was closest to the Russian frontier. Next to Zalosce (or Zilozitz in Yiddish) that belonged to the Zborow district was a short border with Russia. Zborow, a typical podlit [feudal city], was on the main road between Zloczow and Tarnopol. It connected them via highway and railroad.

[Page 20]

In 1914, Russia conquered and engulfed eastern Galicia including Podwolochyska, Zborow and Zalosce. The major bridge over the rail line near the village of Pluhov close to Zborow was mined and blown up immediately.

The city ground hid the footprints of past wars. For instance, when digging up foundations of a house uncovered human skulls, broken swords, utensils and coins. Not far from Zborow, there was a village, Tustoglowy, “100 heads” in Polish, where in fact 100 soldiers were buried. Between Zborow and Zloczow there stood a monument over the mass grave of those killed by the swords. This place was called in Polish “Mogila” meaning Memorial Monument.

In Polish history books used in schools, Zborow is mentioned as an arena of many battles. Among others Samuel Zvorovski is mentioned as one of the important commanders.

Many hypotheses exist as to the source of the Zborow name. The correct one seems to be the Ukrainian name “place of gathering.” Even its spelling varies. In pre- WWI Russian books the town is called Zborow, while the Soviets called it Zboriw, which sounds Ukrainian. Poles and the town Jews used the name Zborow. Rabbi Natan Nata Hannover, in his book The Bottom of the Sea (the Hebrew name is taken from Psalm 69), mentioned the town using its Russian spelling. This spelling (Zborow) also appears in Gershon Bader's description of our town called “Our small town that brought forth great people.” In New York, people from our town have a completely new idea and refer to the survivors as Zbarower countrymen.” I prefer writing “Zbariw” used by the previous generation in the community records and the seals of the religious schools or the name Zborow as used by Yehudah Labiner's articles in Hebrew newspapers of that time.

I know little about the Jewish community leaders of old Zborow. I found the complete record of the community council of 1913-1914. Shimon Buchwald, a wine merchant, was this council president and with him other members of the upper council included: Eliyahu Auerbach, an innkeeper, Yitzchak Lipsker, a grain merchant; Yakov Perlmutter, a banker and owner of a major textile store in town; Aron Czapnik, banker. Other members of the council included: Zisha Berger, a carpenter; Mendel Byk, a shopkeeper; Yehuda Labiner, a teacher; Shalom Lechowitz, a merchant and broker; Shmuel Hersh Schechter, a mohel and merchant; Moshe Spindel, a shopkeeper; Hersh Stoltzenberg, a clerk for a Christian lawyer; Meir Unger, owner of an “iron store” and Nata Zimmer, owner of a flour shop and tombstone engraver.

After completing the chapter on the historical background of Zborow, I visited the Jewish Institute of Literature and found in the 1889-90 “Literary treasure” additional detail concerning our town that is worth pointing out, namely:

“Zborow (Latin spelling)-(Zborow in Hebrew letters) a town in Galicia. Near this town a fierce battle took place between the Cossack army and the Poles led by King Casimir. They cut and devoured each other like bereaved lions. Finally the Cossacks surrounded the Poles. The King was suddenly in great danger. Khmel'

[Page 21]

had the upper hand and captured Casimir. The victorious, however, regretted his action and shouted “Stop” and signed a peace and friendship treaty with the defeated king (in August 1649).”

The author mentioned additional details already mentioned above.

There are probably other details about the history of our town and its Jewish community but they are difficult to find.

The writer of this chapter did his best but does not consider himself as an expert historian. He hopes that others can complete the task.

|

|

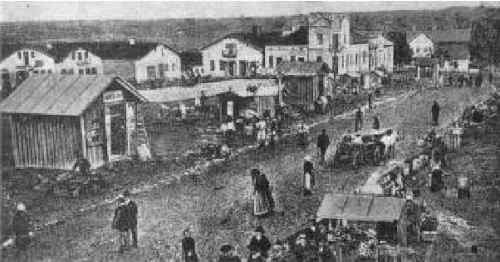

| The Market Square (Rynek) before WWI |

by A. Silberman

Translated by Rena Berkowicz Borow

Zborow was a central city in the region of Tarnopol, USSR, located on the banks of Strypa River, which flows into the Dniester near the Zborow station on the Tarnopol–Lvov line. Zborow became known for the battles fought in its vicinity in the 15th century. Currently it is home to a large number of factories and local commercial activity. In 1952, the city had schools up to 7th grade, a culture hall, and a movie house-theater. The city is, in part, an agricultural center and area farmers grow wheat and sugar cane. Many also raise cattle for milk and meat.

The Battle of Zborow 1649

The battle between the armies of Bogdan Khmelnytski and the Polish King Jan Casmir broke out when the Ukrainians were fighting to free themselves from oppression by the Polish nobility.

After the defeat of the Polish Hetman armies, peace talks were initiated between the Polish government and Bogdan Khmelnytski, but brought no results, and the Polish nobles again directed their troops toward Wolyn, Podolia, and Galicia.

|

|

| Map of 1649 Defeat of the Poles near Zborow, August, 6, 1649 |

Ukrainians everywhere rose to combat the Polish nobility. In the first half of 1649, Khmelnytski declared war and was joined by the forces of Khan Kyym Islam Giray. The first confrontation occurred on July 3rd near Zborow and resulted in the retreat of the troops of the Polish Hetman Wishnevsky into the citadel of Zborow. The siege lasted until August, when the Polish king amassed some 30,000 new soldiers. When Bogdan Khmelnytski learned of this, he left part of his army behind, and he himself led an army of 60,000 Cossacks and 100,000 Tatars to attack the enemy. The Cossacks reached Zborow and camped in the woods in the eastern part of the city, undetected by the enemy. The next morning, August 5th, the Polish army began building bridges over the Strypa River and crossing over to the other side without previous reconnaissance. By noon, half of their soldiers had crossed the river. Then the Cossacks and Tatars attacked from behind and the battle raged until nightfall. The next morning, at 6 AM, the fighting resumed and the Cossacks and Tatars stormed into the city of Zborow and then moved on to Wagburg. The Ukrainians did not obliterate the Poles only because they were betrayed by Tatars who were paid off with a fortune in gold by the Polish king and forced Bogdan Khmelnytski to end the war and agree to a peace. On August 8th, 1649 a peace treaty was signed.

[Page 23]

The Zborow Peace Treaty of 1649

The agreement was signed by King Jan Kazimier of Poland and Bogdan Khmenlnytski on August 8th after the Ukrainian armies routed the armies of the Polish nobility near the city of Zborow in western Ukraine [it is actually an eastern Ukrainian city].

Bogdan Khmelnytski was forced to sign the agreement because he was betrayed by Khan Giray at a critical moment in the battle, when the Polish army was all but decimated.

After the treaty was signed, Ukraine won partial independence, gaining control of the regions of Chernigov, Kiev, and Bratislav, and henceforth Poles and Jews were barred from setting foot in those areas.

Significant Dates in the History of Zborow

On the order of King Jan the 3rd Sobieski of May 9, 1689, the Jews were granted rights equal to those of official residents of municipalities. The order states: “Jews are entitled to seek justice from the local authorities, and if the rural official or the mayor obstructs these rights, he will have to answer to our commissars. The official is to take the local residents and the Jews under his wing and to guard them from passing armies or local security forces.”

To improve the economic condition of the local residents and Jews, the King granted permission for 4 market events a year, as well as permission to set up stalls and sell wine, but stipulated that non-Jewish residents have right of first refusal.

Under Austrian rule, a school was opened and operated until 1796.

In 1910, a school was founded with financial support from Baron Hirsch (1893).

In 1765, 655 Jews lived within the city of Zborow; including the outskirts, there were 845.

In 1900, the Jews of Zborow numbered 2,084, close to half of the total population.

In the year 1649, on August 5-6, a treaty was signed between the Polish King Jan Kazimier and Bogdan Khmelnytski, after the king was defeated in the war against the Cossacks and Tatars. The terms included the stipulation: “Jews are forbidden to own property in cities where Cossack troops reside or are quartered.”

|

|

| Overview from Mount Tustoglowy |

by Yehudit Katz

Translated by Daniel Kochavi

Edited by Daniela Wellner

Like many Polish towns, Zborow did not have a detailed history to help in understanding its past nature, spiritual life, personality, and economic life. In those days, Zborow's people, like other communities, did not record events or research their past history. They only wrote Torah commentaries, hence the limited knowledge of its history. Based on tales and rumors and hints, one must assume that small Zborow had deep roots in Israel's Diaspora.

In his book, From Zborow to Kineret, R' Binyamin mentions the sayings of the Prague Gaon Yechezkel Landau, reminding us that Zborow was a town of scholars and writers. Tales of blood libels in Zborow suggest that our ancestors knew how to function wisely in times of troubles and did not expect miracles.

Tale of Blood Libels

One day, Grandma Halka, a beggar, was found cruelly beaten up near the church in Zborow. Jews were accused and condemned to death. After a gallows was built in the town square, it was declared that anyone agreeing to convert would be spared and should wear a red hat showing agreement. A few agreed to convert and Zborow Jews hated them for generations. A legend tells of two brave and smart religious scholars (Avrechem) disguised as peasants who left the town to explore the surroundings. They went from one village to the next, stopped at inns and listened to conversations of peasants. According to the legend, two doves appeared and showed them the way to another inn where they overheard two beggars. They talked about how they robbed Halka but could not agree how to divide it. The scholars returned immediately to the town with the good news. The beggars were captured and hung on the gallows intended for the Jews. In memory of this miracle, no Tachanun [Supplication] was said on 12th of Tevet and the Zborow Jews called this date “Minor Purim.”

Zborow Jews under the Austrian Regime

Under the Austrian regime, ruled by the emperor Franz Joseph, it was one of the brightest periods for Zborow Jews. This liberal emperor granted equal rights to all citizens regardless of religion or nationality.

No wars were fought for a long time during his rule. The anti-Semitism that beat in the hearts of the Polish and Ukrainian people was suppressed. Zborow Jews were able to continue their traditional way of life they had lived for hundreds of years. Our ancestors lived humbly in the Diaspora, were content with little, and accepted their hard life. They had no contact with the world around them and dedicated themselves to Torah studies and waited for the coming of the Messiah. This situation continued until the period of Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah).

Beginning of the Haskalah

During the second half of the 18th century and the start of the 19th, the spiritual life of Polish Jews changed. It started with a period of progress and followed by Haskalah that flourished together with other factors in the environment of economic changes that took place in Germany and White Russia. The affluent merchants and Jewish manufacturers were the first to change. Their large businesses put them in frequent contact with this new influential world. They were influenced by German culture and lifestyle. They were the early swallows announcing this new world

[Page 25]

full of changes and innovations. The 19th century was a stormy time. Jews started to observe the world around them differently, and started to wisely and logically analyze its contents. This undermined the faith in religion, society, and economics resulting in revolutionary movements in general and particularly in the Jewish world.

The Haskalah movement in our region appeared first in the large cities: Lvov, Brody, Tarnopol. In addition, the commerce was well developed. It was followed by contests against the ironclad rules of tradition. As a result, the quiet lives of the Jews in the large cities turned more dynamic. A rebellious generation arose who wanted freedom and change of value that led to the rise of the Zionist movement that branched out to various youth movements on one hand and assimilation and extreme left movements on the other.

Echoes of the Haskalah reach our town a little later. The atmosphere started to feel freer. The longing for books rooted in Zborow's people did not stop even during these changing times, but with new trends befitting the period. In spite of the internal restrictions of Jewish life, there came a desire to become acquainted with the outside world and to join the Haskalah movement. Zvi Zwerdling, a teacher and major intellectual, was one of the first as mentioned by Meir Halevi Matrist, who stated that he (Zvi) was one of the great Hebrew language experts. He formed a group of the finest town intellectuals. These early rebels devoted themselves with all their hearts to the Enlightenment. They studied diligently the Tanach, linguistics, Ashkenazi (Germany) and its poets, and the writings of Mendelssohn. Inspired by the classic German literature, they translated poetry and dramas.

In Zborow and other towns in Galicia, the ultra Orthodox opposed the Haskalah and early proponents studied secular subjects in secret. Members would meet in wheat fields and study in groups or individually. Prominent members of the Haskalah (Maskilim) in town supplied the best books and met in the seminary (Beit Midrash) at a designated corner where they discussed and argued the important world issues of the day. Yitzchok Auerbach was a well known poet of that time. He wrote in Yiddish, composed lyrical poems in the spirit of the time, and wrote noteworthy plays that were performed in Lvov and other places.

Zeinvel Rota was another author who wrote in Hebrew. He is better known for two elegiac poems mourning the death of two doctors, Dr. Kronisch and Dr. Nagler, who contributed widely to the knowledge of medicine and science in town. There were of course other writers whose names did not reach us.

Last but not least is R' Binyamin, z”l, our great author of this period, who drew from the well of Torah and secular culture. He was an inspired writer who made major contributions to immortalization of our community in his book From Zborow to Kineret.

We should mention the Baron Hirsch School, a top school that made many contributions to the education of the younger generation. Some outstanding teachers included Malkisz, Gezelt, Waltuch, and Labiner. We recall especially its director, Yehuda Labiner, z”l, an outstanding Jewish scholar who was devoted to tradition as well as the Haskalah movement. Being imbued with national spirit, he promoted among his students and their parents the idea that the youth had to prepare and train for labor and trades and join the Zionist movement. In those days, this was very daring since traditional religious life dominated and the aversion toward labor had not yet ended. Yehuda Labiner was also a journalist. Many of his students were influenced by his superior training. Several students live in Israel and some in the USA. They all remember fondly their devoted teacher.

by Mordechai Marder, z”l

Translated by Daniel Kochavi

Edited by Daniela Wellner

The history of Zionism in Zborow follows its history in Galicia. This movement started with the appearance of Theodor Herzl. Representatives of Galicia Jews, including selected members of our area, attended the first Zionist Congress [1897]. One of the leaders was R' Itsikl Schwadron from Binayov near Zloczow. R' Itsikl, a man of high ethical standards, ennobled the spirit of all the Jewish communities in our area, including Zborow. When R' Itsikl visited our town, the community leaders allowed him to speak in the Beit Midrash Hagadol [the great Torah Study Hall] because his brother was the Gaon R' Mordechai Schwadron from Brzezany. His passionate heartfelt Zionist speech was the first of his kind heard in our town. His words made a deep impression and we carried them in our hearts and considered them with great enthusiasm.

The “teacher” R' Hersh Michal Berishes (Zwerdling) was another personality that conquered the heart of our town. He brought to our young generation the Zionist ideas, the old and new literature that renewed the idea of revival. Although R' Hersh was old, his young spirit, energy, and activism matched those of the youth. Half of town people were his students including the notable “upper class” (baale baytim). They were all under his heartfelt influence. The Chassidim referred to him as a misnaged (opponent) and the Orthodox

|

|

| The main street |

[Page 27]

an apikores (denier of the faith). All, however, recognized his integrity and humility. He was beloved and admired by his students, the youth, and all others in our town. To us, he was not just a teacher, he was a friend whose teachings fascinated us. He possessed a poetic spirit and, when inspired, he would write poetry. This poetic spirit inspired his lectures. He would read selected chapters of the Tanach as well as excerpts from the newer literature that proclaimed the ideas of freedom and national revival such as the poems of R' Yehuda Halevi and “Ha-avat Zion [love of Zion] by A[vraham] Mapu. He never imposed his views, nor did he preach to us. He made us love the Tanach! When we read with him with faith and devotion the exalted morals we sensed his identification with their anger and pain and through him their “spiritual nobility” became part of us. The words of the prophets were not just “scholarly commandments” but exalted poetry causing deep yearning in our hearts. His teachings were not biased to a particular point of view. Without realizing it, we felt carried away by the spirit of the prophets, following the footsteps of Yehuda Halevi and the heroes of “Ha-avat Zion” dreaming with them of Zion.

These exalted teachings gave rise to a refreshed Zionist journalism. Die Welt was the first newspaper to be published. Then Tagenblat appeared in Lemberg (Lvov), which I distributed in our town, at 5 greitser each (5 prutot). Later, the “Folks-Calendar” by G.B. Adir appeared and Hamagid in Krakow, with the participation of the Zionist Leibl Taubes and others. His article “I am looking for my brother” created a storm of pride in the heart of our youths. This column appeared weekly and I recall that we were fascinated by it. We read it several times with youthful enthusiasm and could not wait for the next installments. The leaders and upper class did not belong, God forbid, to the dark zealots, in contrast to the Belz leaders for instance who fought mightily against Zionism. They [the Zborow leaders] did not dismiss us or mocked our discussions. They observed, criticized, and expressed skepticism based on their knowledge of the world and its mistakes. They treated us and our ideals coldly and without sympathy.

Aron Czapnik was one of the distinguished intellectuals in our town, and perhaps one of the better known in our district. His home was alive with outstanding culture. He reflected about the ideas of both new and ancient philosophers. He did not however participate in community affairs. He was a rich and successful banker. He was indifferent to the renewal movement as if it was a “Chinese” movement. He was a free thinker but on Shabbat he wore a shtreimel [fur trimmed hat] when he went to pray in the Beit Midrash to please his rich father-in-law, R' Yakov Katz. The youth resented this man, who was supposed to be their leader and guide toward their goal but instead was aloof and showed no interest in any public activities. His indifference and the coolness and critical attitude of the city upper class leaders frustrated the youth and, for a few, led to disappointment and despair.

We were saved at that time by the appearance of a new star in the Zborow skies R' Yehoshua Redler, who later became known in Israel as the author “R' Binyamin.” He was the grandson and great grandson of a rabbinic family. His father, R' Israel, was a well known scholar and strictly observant. The extreme pedantic Orthodoxy of Bracha, his mother, was “the talk”

[Page 28]

of our town. Yehoshua Redler at the age of 17-18 was an assistant in the Beit Midrash. On one hand, he was conversant with the Halacha; on the other, he was fluent in Hebrew and German and interested in the larger world. He gained the respect of the town leaders because of his knowledge of the Torah and his family background. The youth also respected his enlightenment and his keen interest in the wider world.

Yehoshua was deeply influenced by Herzl's book Judenstat and embraced the national Zionist movement. He constantly argued with young and old to convince them of the expected deliverance to the Jewish people by the Zionist movement. Being close to the Orthodox circles he argued with R' David'l Kleinhandler and convinced him. Afterwards, the Rabbi asked: “All this is well and good, but tell me, Shayele (Yehoshua's nickname), what will happen to Shabbat in the state you will build in the Holy Land? Will the trains and police rest on that day?” Yehoshua's answer never reached me, but I am sure that it convinced the Rabbi.

The power of Yehoshua Redler's arguments is illustrated by the following story:

In the 1890s, A. H. Facher, born in Zloczow, close to our town, moved to Zborow from London. While a student in Zloczow, or he joined the revolutionary movement and had to escape abroad from the police and settled in London. There he continued his activism and was one of the speakers in Hyde Park. He married a woman from our town. When she became ill he had to leave London and move to our town. He distanced himself from the Jewish community and even on Yom Kippur did not go to synagogue. He would eat treyf (non Kosher) food in public. This Facher was boycotted by the Jews. Even in the Gentile street where he lived, he remained totally isolated. It became public knowledge that Yehoshua Redler formed a friendship with Facher, and it turned into a scandal. The Orthodox Jews feared that he [Redler] would stray. We, the youth, feared that our movement would lose its inspirational leader. But we were all surprised that this Facher, a sworn anarchist, became a nationalistic Jew. This illustrates Yehoshua's great convincing power and influence of this Yeshiva person, an assistant in the Beit Midrash, who wore a black kapota [long coat worn by Orthodox men], with a small beard and two long and straight payot. Redler won over this hard-nosed anarchist, acquainted with the wider world.

At that time, Dr Abraham Salz appeared on the scene of the Zionist movement in Galicia. He belonged to the Pragmatic Zionism while Redler supported Herzl's political Zionism. Nevertheless, they cooperated in the public domain. Yehoshua expressed his views as follows: “Political activism and practical work are both required in the country. Seize the one but do not neglect the other.”

These two men started a special project that was new for Galicia in those days, namely, fund-raising for settlements in Eretz Yisrael. As a matter of fact, I was drafted for this project. It happened on Yom Kippur, even when I was 14 or 15 [1897 or 1898]. Yehoshua Redler gave me a daring task: I was to stand at the table where donation bowls were placed for various charities as was the custom in Synagogues on Yom Kippur eve. I went to the designated tables of one of the Zborow synagogues. Anxiously, I placed my bowl

[Page 29]

at the edge of the table. Immediately, one of the gabais (Synagogue religious officers), who were in charge, shouted: “Voos is Dahs” [What is this?]. He was the Talmud Torah (religious school) gabai. I did not answer or react, just pretended that I did not hear him. He immediately grabbed me by the collar and threw me out with my bowl. At that moment, my fear left me. I wanted with all my might to achieve the task given to me by Yehoshua Redler. So I went back and placed the bowl on the table. The gabai could not believe his eyes. I became full of courage and daring and stated forcefully: “My cause is more important than yours, and if you remove my bowl I will remove all the other bowls!” The chief gabai, R'Yakov Katz, turned to his friend and said: “Calm down R' Yitzchak, if he wants to stand here then let him. No one will pay attention to his bowl.” So I stayed. The donations were small but the moral encouragement was great. With a great show, R' Mendel Byk contributed the first krona to my bowl. He was one of the secret supporters of our movement and a steady reader of the “Magid.” Later when we met, Yehoshua Redler said: “You are the first one to survive the baptism of fire, and you must continue on this path to remove the obstacles standing in our way.” This encounter created a friendship that lasted to this day (1935) and made me very proud.

One of the important tasks given to us by Redler was the distribution of the Actisia [shares] of the Colonial bank. One share sold for 12 reynish, an amount that exceeded the normal contributions in those days. We, therefore, enlisted the help of the highly respected R' Leibl Taubes, after he published a series of articles titled “I ask my brother.” He joined our presentation meeting. Interest in his brilliant speeches enabled us to sell 70 shares and even attract additional people to our ranks; among them, Tzvi Nagelberg and his brother-in-law, Shimon Schechter, who in the meantime had already emigrated to Israel.

|

|

| Food distribution during WWI |

[Page 30]

Yehoshua Redler created a well organized movement. He rented a hall for our club in Sander Segal's house, who turned out to be a very patient landlord. Although we did not pay rent for many months, he never bothered us. Redler organized the first chanukah [dedication]. He invited the best speakers and Hersh and his choir entertained us. The biggest surprise was Redler's speech in Hebrew. We were all enchanted by his polished language. Even the Orthodox Jews who opposed our movement came to hear this miracle, a live speech in Lashon Hakodesh [the holy language, Hebrew]. R' Gershon Bogner, an Orthodox scholar in our town, was moved to tears upon hearing Yehoshua Redler speaking in living Hebrew.

As part of his energetic activities, Redler continued to learn and grow. He immersed himself in the articles of Ahad-Ha'am [a contemporary Zionist essayist, Asher Tzi-Hersh Ginsburg]. He read the important world literature in addition to Hebrew authors. He was a believer in political Zionism and did not hesitate to write in “Achiasef” [likely his publication Luach Achiasef] an article critical of Ahad Ha'am's, whom he greatly admired. This was considered a very daring action.

Especially surprising and daring in its novelty was his decision to explore the outside world. His closest friends, including me, could not believe that this man, an assistant of the Beit HaMidrash, would dare to immerse himself into this wide world unknown to the Israel youth. His decision to go abroad felt like a youthful fantasy. We knew that he did not have the financial resources to support himself. Nevertheless, he went on his way to the unknown having only enough money to cover the travel costs.

In his first letters to me, he described his first impressions of the cultural life in Berlin with all its wonderful confusion. He especially dreamed of creating a similar cultural corner for our people in Eretz Yisrael. His letters reflected this desire. His dream was to create in Israel the culture and art he discovered abroad.

Even after Yehoshua Redler left Zborow, his influence on the Zionist movement in our community continued. Few felt very proud when his writings first in Germany then in Israel became well known. We followed his example and he became the standard for all our actions. Each of us dreamed secretly to achieve even a modest goal that would fit one who considered himself a friend of this businessman and famous author R' Binyamin from our town. We were all proud of his friendship in the past, and have followed his direction in the present, partners in his dreams for the future and proudly carry the blue and white flag in Zborow.

In the first years after Redler's departure, the movement was headed by Eliezer Taler, a religion teacher in the Baron Hirsh School. He organized a Zionism conference in the Pomorzany district. A delegation attended from Zborow headed by Tzvi Nagelberg, an estate tenant in the village of Jaroslawice. Also attending this conference were: Abraham Morgan, Meir Zoller, and the author of this article. Presiding over this conference was the devoted Zionist Mr. Maiblum from Brzezany, father of Dr. Maiblum, a Zionist leader from Zloczow. This conference of took place in an old wooden shack without the bells and whistles of the present. In spite of this, an enthusiastic true spirit of the “Chibat Zion” (love of Zion”) prevailed.

After them, others assumed a respected role in the Zionist movement: Mr. Gruber from Orlov, Mr. Josef Osterzetzer, and Shmaria Imber, whose brother composed our national anthem “Ha Tikvah.” S. Imber was a religion teacher in Jezierna. He also organized Hebrew lessons

[Page 31]

in Zborow and acquainted us with the Hebrew Zionist literature including Barkai by Naftali Hertz Imber. And last but not least: Dr Israel Waldman from Tarnopol (today one of the Radical Zionist leaders in Vienna 1935) and Dr Philip Korngrin (presently a Judge in Haifa, 1935). These two worked tirelessly and traveled from one Jewish community to the other in our district. They were outstanding speakers and enthusiastic preachers. They also visited Zborow and converted souls to the revival movement including groups who until then would not join us. Among the adults who joined us were David Feuerring and Yakov-Asher Tahler.

The personality of A. H. Facher, the “repentant” is worth mentioning again. He was “the revolutionary rebelling against monarchy” who became a “national” Jew thanks to Yehoshua Redler, as discussed above. He became involved in the Zionist youth movement. He was one of the first to encourage the youth not to fear the fight for the rights of people and citizens. These efforts led to his election to the city council as the only Zionist member representing the nationalistic community and its civil rights in the town.

His other ambition was to be chosen as the representative to the Eleventh Zionist Congress for the communities of Zborow, Jezierna, and Zloczow. We presented him as our candidate. But his opponent, Dr. Hersh Oren from Jezierna, who was younger and more energetic and who had social and work connections in Jezierna and Zloczow, was elected.

We must mention Zborow's contribution of 100,000 kroner to the first Hebrew Gymnasium “Hertzelia” in Eretz Yisrael. Mr Gershon Tzipper stayed in our town for this cause in 1912 and we responded with this donation.

The Zborow Zionist group was deservedly called “Brotherhood.” The best of the town youth was united in a spirit of brotherhood around the central ideal of the movement. This foundation taught democracy and mutual tolerance to our youth. Members of the Brotherhood participated in all the public enterprises of the town. I recall the population census of 1910. The Zionist slogan was: Jews list yourselves as Jews and declare Yiddish as your mother tongue! The members of the Brotherhood devoted much efforts and dedication to this project and were greatly disappointed by the results. They joined this project because of their deep national conviction. The project was however run by the old leaders isolated in their institutions, so the youthful voices did not reach them.

Only three Jews declared Yiddish as their mother tongue: A.H. Facher, Josef Schachter, and the author of this article.

Afterwards, by the editor and translator: (from Yiddish to Hebrew by the author's son-in-law, Shaul Yardeni)

After the horrifying Shoah visited upon our people, and since Zborow is not among the remaining Israelite communities, these stories that memorialize Zborow and its holy community that perished in the Shoah are of great importance.

The writer gave the original text to R' Yehoshua Redler, z”l, “R' Binyamin”

[Page 32]

from Zborow and a friend of the author, wanted to translate it to Hebrew for future generations. Reaching old age, R' Binyamin was not able to achieve this goal. He turned to the author's daughter, Hanna Yardeni, and asked her to take up this task and to publish it in order to memorialize Zborow and its sacred community.

A reliable witness who survived the Shoah recounts the last days of the author, z”l:

When R' Mordechai Marder, z”l, saw the destruction of his people, he and wife Rosa, z”l, lost hope of joining their children and family in Israel he said: “I was relieved that my children escaped annihilation and I decided there and then that I would not be led like a lamb to the slaughter and if my fate is death–I shall die here.” And indeed when the soldiers came to arrest him, he fought them and they shot him in front of his house.

|

|

| The bridge over the river Strypa that connected the town with its neighbor Kuklince |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zborov, Ukraine

Zborov, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Aug 2024 by LA