[Page 31]

Education,

Culture and Journalism

Jewish Education

By David Niv

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, Jewish education in Volkovysk was traditional almost in its entirety. However, even in that time, there were young boys and girls who were educated in Russian schools, but this was a small minority. There were very few local teachers who gave lessons in general and Hebrew studies. Basic education was given in a Heder and a Talmud Torah, as was the case with all of the cities and towns in the Pale of Settlement, and education was then continued in a Yeshiva. Among the teachers who stood out during this period were: Moshe-Meir, Hona Jesierski, Eli Bultvar, and Aryeh-Leib Friedenberg (Leib-Ahareh), and they were supported by ‘Assistants.’

With the passage of time, more modern Heders were established, in which Hebrew grammar and literature and Hebrew poetry were taught in addition to Pentateuch with Rashi and Gemara. With the development of the modern Heder, and their expansion, local language, arithmetic, physics and other general studies were added. Among the schoolmaster and teachers were: Israel-Meir Rubinstein, Skop, Nakhum Halpern, Farber, Shlomo Sukenik, Zvi Levinsky, Boruch Zusmanovich and Reuven Rutchik. In a number of these ‘modernized’ schools, studies were conducted entirely in Hebrew (Ivrit Be'Ivrit). Apart from the Heder system, a Talmud Torah (Takhkemoni) also existed in Volkovysk up to the Second World War, in which the students were mostly from the poorer levels of the community, and only 20% of them paid tuition. It is known that in 1929, there were approximately 250 students in the Talmud Torah. In addition to learning prayers, Torah and Prophets, Tosafot commentaries and Torah cantillating, the curriculum included Hebrew grammar, Jewish history, and also secular subjects such as: geography, nature, local language, and arithmetic. On average, nine teachers taught in this institution.

The yeshiva was founded in Volkovysk in 1887 by the Rabbi of the city, Boruch-Yaakov Lifschitz, author of the book, Brit Yaakov,[1] and it was significantly expanded and developed by Rabbi Abba-Yaakov Borukhov, the author of Hevel Yaakov.[2] Rabbi Yerakhmiel Daniel, the headmaster during one of its later periods, had a reputation for being a thoroughly versed scholar in the Shas and its Commentaries, and was held in esteem by all the Jews of the city. In the final years of the twenties, the Jewish community of Volkovysk established something of a ‘kibbutz,’ that is to say, a Yeshiva where students came from the outside, and ‘ate days[3]’ at the home of the balebatim of the city.

In the area of general education, a grade school was opened in the city back even in the days of Czarist Russia, consisting of four grades, and most of whose students were Jewish. The language of instruction, naturally, was Russia. This school didn't last long, and was closed in 1909. In time, a Byelorussian government gymnasium was opened in the same building, which operated until the outbreak of the First World War. During the war years, many Jewish students studied at a compulsory German school.

The Yiddisher Volksschule, a public school, was opened in 1919, and the curriculum was taught in Yiddish, and several hours a week were set aside for instruction in Hebrew language. There were four grades in this school, and also a kindergarten. It is also worth noting that after hours, there were evening classes conducted in Yiddish.

Most of the Jewish children studied at Hebrew schools, which after the First World War, came under the direction of a committee. While still under

[Page 32]

German occupation, after the outbreak of the First World War, due to the efforts of Yehuda Novogrudsky and Moshe Rubinovich, a Hebrew kindergarten was established, followed by a grade school established by the Tarbut group, and in 1926, gymnasium studies were launched with the arrival of the Hebrew gymnasium, Hertzeliya, known in its formative years as Progymnasia.

Graduates of the modern Heder system were among the gymnasium students, but the majority of the students were graduates of the grade school. Tuition free education was made available, in the gymnasium as well, for the children of needy families, and also to residents of the local orphanage.

In the 1928-9 school year, the gymnasium received the endorsement of the Tarbut organization. Originally, there were only 6 grades, and those who were interested in continuing their education, were forced to transfer to other cities (like Bialystock, Grodno, Vilna) to complete their education in seminaries or the upper grades of high schools, but in 1932, the seventh and eighth grades were added. This is the manner in which studies were conducted up to the outbreak of the Second World War, and the entry of the Soviets into the city, which led to the closure of the school as a Jewish institution. The last principal was Dr. Mordechai Sakhar, and among the teachers of Hebrew literature – one of the most important subjects of that era – Yitzhak Shkarlat and Dr. Israel Scheib (Adler) stood out. Dr. Scheib came to Volkovysk to teach Hebrew literature in the high school with a career purpose in mind, because other Hebrew subjects were being taught there according to the gymnasium curriculum, and from there he went over to the Hebrew gymnasium.

In the early thirties, a grade school from the religious Yavneh movement was established in Volkovysk, and in 1931, a Kadima grade school was established, under the supervision of Yaakov Neiman, in which the language of instruction was Polish. He used curriculum of the government school system in Poland, and in addition to the general studies, they also studies Hebrew, Tanakh, and Jewish history.

Hebrew education in Volkovysk bore important fruit for Hebrew culture and the Zionist movement. Many students and teachers emerged afterwards with their contributions to Hebrew culture and the Zionist movement in many countries, especially in Israel, to which many of the teachers and graduates of these institutions came.

Translator's footnotes:

- Literally, ‘The Covenant of Jacob.’ Return

- Literally, ‘The Halyard of Jacob.’ Return

- This was a form of meal subsidy provided by the more well-to-do families for out-of-town Yeshiva students. Return

The First Rungs

by Yehuda Novogrudsky

|

|

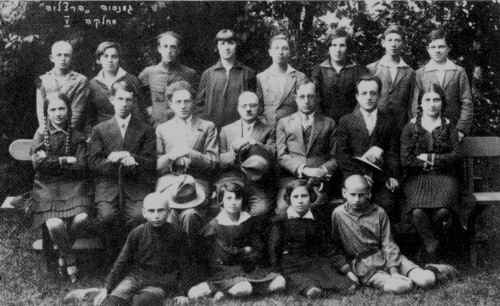

A group of teachers from the Tarbut Gymnasium in the year 1932

Right to left, first row, bottom: Miss Zilberman, Fishl Weinstein, Miss [Batya] Landsberg

Second Row, Seated: Eliezer Kapelyushnik, Rothfeld, Luvoshitsky, Moshe Rubinovich (the Founder),

Yud'l Novogrudsky (the Co-Founder), Miss Berliner1[1]

Third row, standing: Zilber, Hannah Turbovich, Y(itzhak) Itzkowitz, Hedva |

|

|

The Sixth Grade of the Tarbut Gymnasium prior to the aliyah of the teacher, Namlin |

|

|

Fifth grade picture of the Hertzliya Gymnasium |

|

|

The first graduating class of the Tarbut Gymnasium |

In Dr. Einhorn's Book, Wolkovisker Yizkor Book, Yehuda Novogrudsky, one of the pioneers of Hebrew education, tells how the Hebrew educational institutions were established, and by whom.

[Page 33]

The first tier was the establishment of a Hebrew library with minimal effort, and the development over time to the point that it became the center for “Lovers of the Hebrew Tongue” (one of them was the gymnasium student Raphael Lemkin, who later became prominent in time as Professor Lemkin, an expert in international law in the United States) and all those dedicated to national rebirth. The first national educational institution was a kindergarten. Y. Novogrudsky writes:

“I remember that Moshe Rubinovich and I would go from door-to-door, in order to convince the parents of children to send their children to this kindergarten, which in the view of many was a strange institution and superfluous, because all the children seemed to learn there was how to play, sing and dance. It didn't take long, however, before this kindergarten earned the affection of parents, who became convinced of the great value that it provided, in that it served as an antechamber for entry into the Hebrew grade school. Moshe Rubinovich, who can be seen as one of the pioneers of Hebrew education in all of Poland, would argue before me: “God forbid that we be deterred by difficulties.” The establishment of a Hebrew school is an imperative, and it cannot be delayed. Our public servants and elders, Ephraim Barash and David Hubar have looked after the establishment of a Russian school on the Lazaret Hill, and it is left to us to concern ourselves with the need to educate the young generation in Hebrew language, and with the spirit of national rebirth, and that they absorb, from early childhood, the spirit of the Prophets and Hasmoneans. Only in this way will a generation grow up in possession of national identity, paving the way for a bright Jewish future and national liberation.”

Novogrudsky continues:

“Hundreds of children studied at the school that we established. Poor parents did not pay tuition, and many were taken for nominal fees. The teachers were accomplished pedagogues, among them highly enlightened people. Among the teachers, whose contribution was especially important, it is worth recalling Zvi Carmeli (Weinstein), who then emigrated to the United States, and Azriel Broshi (Berestovitsky) who made aliyah to Israel and earned recognition as an employee of the Histadrut who was outstanding as a tourist guide. It is appropriate to take note of Aharon Luvoshitsky, among the principals of the school, who was a Hebrew poet, wrote many textbooks, and edited a Hebrew newspaper for the youth, Dr. Shafel, a master teacher, following the ideas of Gottesfeld.”

Novogrudsky elevates the extensive work done by Moshe Rubinovich, who neglected all of his business obligations and gave himself over heart and soul, with all his energy to the opening of the school and its expansion, and here are his words: “Images of those days come to mind, when we would receive a parent coming to register a child with a joyous, full and trembling heart. We would sit in the unused rooms in Pappa's house on the Grodno Gasse, on the long winter nights, shivering from the cold, engaged in disputed with the array of teachers over the curriculum. – our school served as a model for the surrounding cities and towns, who also established Hebrew schools, that inculcated the concept of national rebirth in the hearts of their pupils and their families. By means of these schools, not only were the students transformed into ardent Zionists, but also their parents. It is proper to emphasize that the central Zionist institutions in Warsaw viewed Volkovysk as a bulwark of Zionism, also on account of the substantial contributions to Keren Kayemet, Keren HaYesod, and other national funds.

After a grade school was founded, Moshe Rubinovich began to the establish a Hebrew High School – a Gymnasium. He was not only one to have good ideas, but also capable of getting things done. We rented an appropriate premises in the former tobacco factory owned by Yanovsky on the Wide Boulevard, which was renovated to the specifications of a school, and qualified teaching personnel were retained. And on one fine morning, placards were pasted all over the city which informed the public about the birth of the new Hebrew Gymnasium, “Hertzeliya.” The success of the Gymnasium exceeded all expectations. The Gymnasium was one of 16 Gymnasiums in Poland, and quickly was

[Page 34]

transformed into a “spiritual center” for the surrounding province. Students were attracted even from bigger cities, such as Slonim and Baranovich, to the Volkovysk Gymnasium, whose reputation reached afar (it happens that one of the students was Yitzhak Yazhernitsky, today Yitzhak Shamir, a Prime Minister of Israel, who came from Ruzhany to study at this gymnasium).

From the outset, the gymnasium had no government certification, but in the school year 1928-9, when the school was absorbed into the network of the Tarbut movement, specific government permits were granted, which however, did not have much value under the circumstances of the times.

It appears that the nationalist inclination of the gymnasium was not satisfactory in the eyes of some of the activists, who apparently leaned towards assimilation, and their desire was to get full government accreditation for the high school, in order that subsequent to graduation, the graduates would be eligible to be accepted at Polish universities. By 1937, the matter reached the breaking point, when these activists announced their objective – to close the Hebrew gymnasium and to replace it with a gymnasium where the language of instruction would be Polish, and the curriculum would we the same as in Polish schools. They joined forces with the government and the authorities in Vilna, and had planned to transfer all its assets, equipment and facilities of the Hebrew gymnasium to this new institution. By an large, the majority of the Hertzeliya Board, which controlled the Hebrew gymnasium, together with the Principal, Mordechai Halevi Sakhar, strongly opposed the initiative of these activists, who were prepared to do away with the core purpose of the school, and on this matter, very sharp conflicts took place.

Fortunately, the various officials, who came from Vilna to mediate this dispute, established that there is reason to continue the operations of a Hebrew gymnasium, and to undertake the desired expansion. Nevertheless, rumors spread through the city, that the Hebrew curriculum was going to be cut back, in order to permit the expansion of Polish studies, but the Principal denied all of these rumors, and issued a call to the entire Jewish population to continue its support for the Hebrew gymnasium, whose name was then changed to the Chaim Nachman Bialik Hebrew Gymnasium. Descriptions of this entire controversy can also be found in the pages of the local weekly paper, Volkovysker Leben.

Translator's footnote:

- Seemingly erroneous, since the picture shows a man sitting in this position. In place of the given text, this caption is taken directly from Dr. Einhorn's book on page 113 in the original volume. Return

Between Belz and Volkovysk

by Israel Scheib (Adler)

|

|

Fourth grade class picture of the Hertzliya Gymnasium in Volkovysk, 1927-8

At the bottom left: Yitzhak Yazhernitsky, today – Yitzhak Shamir, an Israeli Prime Minister

Second from the right: David Niv |

To My Soul Mate, Nechama Schein

- I.S.

Why suddenly Belz? What do I have to do with Belz? I am a Galitzianer from the womb and birth, but not to this degree…but why? When I began to think about this subject, about which I was asked to write, that is to say, about Volkovysk, the song, Mein Shteteleh Belz rose and floated in my mind, that is sung and beloved not only by the Hassidim and people from Belz. It was my privilege – that Volkovysk was my first shteteleh and also last, in which I lived for about two years.

My first teaching position was in Volkovysk. This was in 5695, or 1935 by the count of the Christians, and not of the people of Volkovysk. The average person from Volkovysk was, naturally, Jewish. Apparently, the Jews of Volkovysk did not have a need for many Shabbos Goyim, and accordingly, there were rather few gentiles in the city (I am assuming the usual joke about Shabbos Goyim is known to the readers). And so, as I said, this was my first position, which I got through an ad in the newspaper that caught my eye. The tone of the ad was something like this: “The Hebrew Gymnasium of Volkovysk is looking for a teacher of Hebrew subjects.” Since I had that very year graduated from

[Page 35]

the University of Vienna and teachers' seminary, I saw myself as having the qualifications to meet the needs of Volkovysk, whose name I had never even heard of until that point, and I presented myself to the distinguished office. The response was positive. I was accepted.

My mother, ז”ל packed my few belongings, and I set out on my way. At that time, there were about six thousand Jews in Volkovysk, by my estimate, most of them Zionists. (Confidentially, my desire is to emphasize that for the information of historians, and plain Jews, especially Israelis, that the majority of the Jewish people in Poland, by all aspects of their activity – were Zionists. The people studies Hebrew, understood Hebrew, and in every way, was more interested in what was taking place in the Holy Land, and involved themselves in it. than what was going on in Poland).

I quickly learned to know that the gymnasium and the youth movements were the center of Jewish life. As was the case in Volkovysk – so it was in the other cities of Poland. There was no obligation to study at the gymnasium, and it did not have government certification. It was a Jewish Zionist education for its own sake. It was a “Hebrew” gymnasium, but that does not mean that everything was taught in Hebrew. That was practically impossible, but the atmosphere was one of Hebrew. The language spoken by the students, as I recollect was a ‘Litvak Yiddish,’ from what I recall of its sound. In Galicia, Polish was more dominant among Jewish youth, but in Lithuania there was a zeal for Yiddish. I never had to wring my hands, ss many Zionist leaders in Galicia and Russia did, who understood the sense of a conversation in Russian or Hebrew, or Polish and Hebrew, but had no knowledge of Yiddish….

The heart and mind of the Hebrew gymnasium was directed to the Land of Israel, even if all the teachers were not active Zionists. The general atmosphere was Zionist, and that's what was important. It was a branch of the larger central educational organization of Tarbut, and many hours were put into the study of Hebrew subjects. And that is where the weight of my work was. There was only one other teacher for Hebrew subjects, and I remember him more than the other teachers, and this is Shimon Gottesfeld, the senior of the group, who was literally a living example of the transition from the generation of the Enlightenment to the Zionist generation. And it seems to me, that he wrote a number of plays based on Tanakh themes that dealt with this subject. For the sake of truth, the greatest and best of my relationships was with the students. In no small measure because of the subject matter of the studies: Judaism, Zionism, Song, Hebrew, Israel, etc.

The youth of Volkovysk was outstanding, and there were no small number among the students who came from the surrounding towns. I loved my work at the gymnasium because of the heartfelt emotions and open and disciplined minds, but I also had other centers of experience in this marvelous town (forgive me, but I think this is my pen running off or the typewriter. I simply forgot that I promised not call Volkovysk a ‘town’), because not only is my first teaching experience bound up with Volkovysk, but also the path of my political life, first there – Betar. I believe it was David Linevsky, today David Niv, who after ascertaining that my disposition was Betar-like, or revisionist (as if I had never been a member of Tzahar), turned to me with the offer that I take over the Betar chapter from him, and he himself made aliyah to the Land of Israel.

It was in this manner, that for the first time in my life, I put on the Betar insignias, and in this manner the direction of my life was largely determined. In terms of basic outlook, my orientation to this direction of Zionism manifested itself as a result of two events. The first event – the Hebron Massacre of 5684 (1924), when I participated with great emotion in a mass protest rally, in which tens of thousands shouted: “Jabotinsky Is Right!” (I heard Jabotinsky himself in the prior year in a rousing speech, and I was at that time in the seventh grade of the Lodz gymnasium, and I remember that speech to this day, but at that time I did not harbor political ideas).

The second event, that influenced me in the direction of Betar and beyond, was hearing the poem of Uri Zvi Ginsberg: I will tell into the ears of a child about

[Page 36]

the Messiah that didn't come. The moving poem tells of a Messiah that comes as far as the foot of the Temple Mount, and there he was found and sold by [slave] merchants. The inference here is also to the issue of the expansion of the Jewish Agency…and especially the pessimistic outcome that the Messiah was thwarted and left, and perhaps for millennia to come, he set the direction: to avoid calamity. The poem was published in Mozna'im in 5691(1931), and I was a student in Vienna. I was involved, at that time, in a variety of activities, and even got beaten during the murder accusations surrounding Arlozorov[1], but as to organized activities, and especially Betar, I began in Volkovysk.

The truth of the matter is, that despite all the comprehension and responsible interest in military discipline and studies, and despite my training in military protocol[2], I did not feel a personal intimacy with being a ‘natural’ for this, but I did not tarry, and I responded to the offer and that is how I became the leader of Betar in Volkovysk, since the majority of the organizational and ‘military’ work fell on the shoulders of my deputy, whose name I believe was Sukenik, who is now in Israel, in Beersheba. My core duty continued to be – presentations, speeches, and written expositions. From the post in Volkovysk, I went on to work in the Vilna valley in 1937, and from there – to the Betar office in Poland at the invitation of Menachem Begin, but it is a strong possibility that were it not Volkovysk, I would have found a different path into right wing politics.

In Volkovysk, I had yet a third ‘primary’ experience after teaching and Betar – a cabinet full of books. This was Uryonovsky's legacy, who was a teacher there, and his cabinet full of books was left behind and sold to me, and it contained a long shelf of ‘heavy’ reading material : all of the volumes of HaTekufah. Naturally, I took it with me, when I went to the seminary in Vilna, but I could not take it with me on my various travels. It remained behind. Well. There were many replacements for it, but there are no replacements for the precious personalities that I left behind in Volkovysk, that we left behind to the fire in all those dear people of Volkovysk.

In one of the first editions of the monthly, “A Ladder to the Ideas Regarding a Jewish State” (Sulam), that I published after emerging from the underground, I published a thought piece of mine as a ‘Memorial,’ to my students, and accordingly, I will finish my writing by copying these words of remembrance here:

A Memorial to the Souls of My Students

…I will remember you too, when I stand this Yom Kippur to recite the Yizkor prayers. Because this year, suddenly I was moved to memorialize all of my students this year, whom I will never see again, and whom I loved so much, all of them. Perhaps this came to me because I could not fulfil my longing to stand, once again, before living students, boys and girls, and teach, and my class is my legs, and my class is my heart, and going from one principal to the next I pleaded: let me stand in front of students. Because I miss them so much. Give me an opportunity, again, to put the spark of my mind in contact with those open hearts to convey portions of poetry and prose, verses from the Psalms and Job. I was taken to prison in the midst of a lesson on Job. And my students in heaven are my witnesses that I taught them to love all of this, but I was eliminated from being a teacher among the Jews. And when I would leave the presence of Principals and administrators, shamefacedly with my heart contracted, I suddenly saw the souls of all my students that I will never see again, because they died, and they surround me and accompany me, with my embarrassed face and contracted heart. And it

[Page 37]

was then that I had the idea to memorialize all of them in a Memorial, since the Yizkor prayer itself is short, short, and the Cantor rushed to interpret the El Moleh Rakhamim so it is pleasing to each person in his own way, so that there is no doubt in a person's heart to feel at one with the multitude, the many. And so I said: I will unite myself only with my students this time, my students of the Volkovysk gymnasium, that town left so in sorrow, those studying to be kindergarten teachers at the teachers seminary in Vilna. You have no parents to mourn for you, or children that you might have born, to remember you. So I will remember you.

I loved you all. The good and the bad. The involved and the indifferent, those that warmed my heart with their eyes riveted on me and my every move, full of emotion and humor at times, and they do not laugh, because they move with the movement of my hands on the waves of the movement of my thoughts, and those that said, “enough,” and those that said “not enough,” teacher, “keep going.” And the special girl students in each and every class, who when they left the classroom, I was saddened, and there was less intensity in my lectures, and those whom I loved to challenge with analysis in order to be able to appease them afterwards with humor, and give only goods grades. I didn't like the teachers' meetings, but I loved you my students, and my joy was literally like that of a child, when my ear would pick up your whisperings during recess: “What a terrific lesson,” even when I knew that those whispers were being said especially for me to hear, but I didn't need it, because in speaking in front of you, I could feel your hearts beating in rhythm with my own, if at all. Because this is what I loved: to join our hearts to all that is beautiful in the literature of our ancestors, so that you could see in Abraham, Isaiah, and Job as people who are living with us today, and that they are great and magnificent, and not as ‘just literature.’ And you helped me greatly. It was your enthusiasm that was fuel for my own soul, and together we flew in the world that was beautiful, good and strong,

My students, my students, I will remember, and my heart years for you.

Sulam, Tishri, 5710 (1948)

Translator's footnotes:

- Born in the Ukraine, Chaim Arlozorov was taken in 1905 by his parents to Germany, following a pogrom there. He went on to become a noted leader of the Labor Zionist movement in Palestine. He was murdered in June, 1933, while walking on the Tel Aviv beach with his wife Sima. The identity of his attackers is the subject of much controversy, remains unsolved to this day. Return

- The use of the phrase, ‘Dom-Noakh’ is explained by David Niv in his memoir. See page 53. Return

A Jewish Girl Student in a Polish Government School

by Shifra Hakla'i (Langer)

|

|

The Stefan Batory Polish Gymnasium in Volkovysk[1] |

When the publisher of this book discovered that I was from Volkovysk, he proposed that I write down my recollections of this city. I said to him: it is more than sixty years since I left Volkovysk, I am an old Jewish lady now, and my memory has faded, what can I remember? He answered: Close your eyes for a few seconds, leap back sixty years, and remember your father, grandfather, mother and grandmother, and the memories of Volkovysk will come to you.

I did as I was told, and here I see a river flowing past the edge of this city, and I even see the place where I lived. It was a dwelling consisting of two rooms in a small house that contained three domiciles. This house was not far from the river, and a garden stood between the house and the river. On the other side – a small lake that froze over during the winter and was used by the residents as a place to ice skate. I can see the cherry tree that grew near our house and also lilac bushes.

Have I discharged my obligation in describing the ambience?

As my eyes are still fixed on this picture of this ambience, when an esoteric melody reaches my ears which is the refrain of a prayer that plays within me. I recognize it. It is the strain of the Kol Nidre prayer on Yom Kippur Eve, but it isn't the traditional melody, but something entirely different. For many years I attempted to locate this esoteric melody on Yom Kippur Eve in various synagogues in Jerusalem, but I could not find it. I found all manner of

[Page 38]

Nigunim, but not this one. It existed only in Volkovysk. I do not remember the Cantor, or who it was that led the prayers, but I do recall that in a thousand dreams, I was drawn to this melody that reached me from the Schulhof in Volkovysk.

We left Volkovysk in 1926 and made aliyah to Israel. In preparation for our transition, we, the children, were afforded the opportunity to be taught by a local teacher, Reuven Rutchik, who taught us Hebrew and instilled in us a foundation about the history of Israel. I did not get this in the Polish government gymnasium, where I was a student. If my faded memory doesn't lead me astray, this gymnasium was a long, one-story wooden building, that stood on a hill at the edge of the city, surrounded by a large yard. Each pupil had a small notebook with a black cover, in which all the rules of behavior expected of the boy and girl students. It was forbidden to deviate from these. The required dress for the girls was – a black apron over normal clothing. I don't remember what the boys were supposed to wear, but I do remember that both the boys and girls wore a special hat with a crease. The Jews were a small minority among the students, and understandably, they felt like a minority. We endeavored, out of a suspicion of being unwanted, not to stand out any more than was necessary… among the teachers, I recall the geography teacher favorably, who had a pleasant manner and was courteous. Also, our history teacher was a gentle and pleasant woman. I cannot say this regarding the priest, who was dressed in a long black cassock, which was enough to upset the Jews. He taught religious studies to the Christian students (the Jewish students were excused from these classes), and he was also the Latin teacher for all the students in the upper grades. Every time we saw him, we were reminded of the fact that we were a superfluous and ineffective minority at the government school.

There were Christian girls among the friends that my sister and I had at the gymnasium. My sister had really good friends among the Christian girls, and I recall that one of them stayed in touch with her even in the years after we made aliyah to Israel. However, this didn't prevent her from asking my sister before the Passover holiday where the Jews hide the blood of the Christian children… my sister was shaken of course, to hear a question of this nature from this ‘buddy,’ but she emphasized that her friend asked this as a question, and not with the intent to either anger or incite.

Translator's footnote:

- Taken from p. 122 of M. Einhorn's book, which names the street as the Lazarovner Gasse, and also note the smithy at the foot of the hill. Return

Teachers and the Heder

by Ben-Israel

|

|

Rabbi Jonathan [Eliasberg] and the Dayan, Reb Mendele [Volk], testing the students |

One of the many portraits done by Shmuel Rothbart, who was known in Volkovysk by the nickname ‘Shmuel Khudozhnik’ ( Russian for an artist). He was born in Volkovysk, and already by the time he was a Heder student, his artistic skill became evident. Under his Pentateuch, he would hold pieces of paper, and secretly draw his teacher, portraits of students, and people in Volkovysk. In 1904, he emigrated to the United States, drew decorative pieces for synagogues, and theater halls as a way to earn a living, but at the same time, he also devoted a lot of time to drawing pictures about his home town, and specific details that he recalled from his days in Volkovysk. In 1917, he had the first showing of his work in New York, which received very favorable reviews and much praise. Many of his paintings can be found in many museums in the United States.

There were many types of teachers in Volkovysk, and it was they who set the various tones of the different. By and large, the teachers had no [formal] qualifications in the field of education, and they saw their role, not to educate the children, but rather to inculcate Torah. An outstanding Heder student was one who could expound on a verse of the Torah in accordance with accepted tradition, knew verses of the Torah by heart, and could review a weekly Torah portion while cantillating. The course of study in these Heders was very antiquated, ‘Once through in

[Page 39]

Hebrew, and once in Aramaic[1],’ as authors like Mendele [Mokher Sforim] Sholom Aleichem and others have described in their stories: “Vayomer – hott gezogt; Adonai – Gott; El Moshe – Tzu Moishe'n, Leymor – Azoy tzu zogn…” Many teachers focused on one ‘subject’ – review of the weekly Torah portion. (According to custom, a teacher was forbidden to take remuneration for teaching, but only for inactivity and reviewing the weekly portion…) On Friday morning, the voices of children intoning the cantillation notes would burst forth from all the Heder rooms and the Talmud Torah: “Mercha Tipkha, Munakh Esnakhta,” and the Rebbe himself would blend in with each ‘Pazeyr’ and ‘Shalshelet,’ that his pupils knew how to intone properly.

After the ‘modernized Heders’ were established, different winds began to blow through Jewish education. The curriculum began to include other subjects, such as: Polish, Mathematics, and even Geography. The Heder discarded its old façade, and put on a new face. Chaim Milkov from Jerusalem knew how to tell about the Heder where he studied, and about the teacher, Linevsky. The wealthy and important balebatim sent their children to this Heder. This was literally a school, and apart from Pentateuch and Tanakh, German and Polish was taught there, arithmetic and other secular subjects. There were two classes in this Heder, and tuition was five dollars a month.

The teacher Linevsky (father of David Niv) followed modern precepts and did not place stock in rote memorization of passages from the Torah, but rather, he pays attention to the degree to which the student understood what was taught. He also knew how to make issues and subjects clear to his students when they experienced difficulty. And it was thus, that when they studied in the Pentateuch about the raiments of the High Priest, about the priest and the Tabernacle, Linevsky would utilizes paper cutouts and drawings that he used to prepare before class, and it was in this way that students got a clear picture of things like the breastplate and caftan of the High Priest, the architecture of the temple, etc. The introduction of this method of teaching was something of a ‘revolution,’ in that era. Also, Farber's school followed these modern practices, and as described elsewhere in this book, that school was considered the most prestigious of all.

Grammar received special attention in all of the modernized Heder schools, and the students of such Heders who then transferred to the gymnasium, excelled in grammar more than other students who didn't attend such Heders. Hebrew, as you can understand was taught with an Ashkenazic accent, and the students did not find the transition to Sephardic easy, during their course of study at the gymnasium. Even the Hebrew was noticeably different from the Hebrew were used to in our day. There was no sabon to be found, but rather, borit, (soap); Ani Chafetz in place of Ani Rotzeh, of our day, etc.,etc. It is necessary to note that many students who studied at Polish or Russian schools in the morning, studied Hebrew and Tanakh in the afternoon, because their parents would not resign themselves to not having their children be able to know Hebrew.

According to Einhorn, David Hubar founded the first ‘Modern Heder’ in Volkovysk, and it was he who made the effort to establish the Russian grade school. According to the same source, David Hubar and Henoch Neiman were the first ones that sent their children to study at the Hertzeliya Gymnasium in Israel.

Translator's footnote:

- Referring to the Aramaic translation of Onkelos, always found in a traditional printing of the Pentateuch. Return

Activities in Theater Arts

|

|

Mordechai (Mottel) Kilikovsky |

Dr. Einhorn describes the beginnings of Theater Arts in Volkovysk in his book. According to his words, these activities began with the efforts of an ordinary man of the people, Mottel Kilikovsky (Cohen). This Mottel, who lost both of his parents while still a

[Page 40]

child, was educated in the home of his grandfather, Sholom Potshter, and while still a child, demonstrated an inclination towards acting. He was in the habit of gathering up the children of the neighbors, and organize ‘military parades,’ with their participation. A Polish doctor, named Yeletz, who lived nearby, perceived his talents, and would occasionally slip Mottel small sums of money for the purpose of buying small drums and horns to accompany the marchers who participated, and in this way a children's military band was formed.

When Mottel reached the age of ten, he began to serve as an assistant to the teacher, Moshe-Meir, and he would organize presentations with the children of the ‘Binding of Isaac,’ and ‘The Selling of Joseph,’ and others. Mottel was 13 years old when he went out into the big world, to Grodno and Kovno. In Grodno, he worked as a barber in a barbershop near a theater, and in this way, he came in contact with the actors at the theater, who brought him in on occasion as a player in their productions, or in some other capacity.

Mottel was 16 years old when he returned to Volkovysk towards the end of the 19th century. The Linat Tzedek organization was established at that time, which was in need of money to buy medical equipment. Someone raised the idea, and maybe it was Mottel himself, to organize a Purim celebration, all of whose proceeds would go to the new organization. The decision was made to put on Goldfaden's operetta, Shulamit, and the director, naturally – was Mottel. It was difficult getting young women for the female roles, and there was no alternative but to have boys play female roles. And it was this way, that the first dramatic production was put on in Volkovysk, in which 16 young people participated. A large crowd came to the first performance, and among others – even a policeman from the authorities, who came to review the play from the viewpoint of censorship…

Even during the First World War, the activities of the drama group did not come to a complete halt. At the beginning of 1916, during the German occupation, Mottel Kilikovsky organized a drama group named HaZamir, and the work of this group continued until the end of the war. The Jewish populace of the city received the work of this group with great enthusiasm, because they longed for Jewish theater. And again, the works of the Father of Yiddish Theater, Goldfaden, appeared on the stage: Shulamit, Bar Kochba, The Sorceress,[1] etc. Most of these performances were put on in Botvinsky's cinema house, and the principal players were: Leizer Sokolsky, Mottel Kilikovsky, Leizer Shiff, and Joseph Pikarsky. The musical director was Israel Schein. The success of the performance of Shulamit exceeded all expectations, and it was necessary to run several repeat performances. The play, Bar Kochba, also achieved recognizable success. The ranks of the Jewish intelligentsia which originally showed no interest in this theater, changed its attitude once it saw that the Jewish public was attending presentation in droves, and even they drew closer to HaZamir. In time, Mr. Galai, a professional Russian actor, took over the direction of HaZamir, and a famous professional Russian actress, Marian, played many lead roles. In time, these theater lovers began to put on the plays of Scholem Asch, Nomberg, Peretz Hirshbein, Yaakov Gordon, and others.

Young people from the surrounding towns would frequently come to Volkovysk in order to enjoy these productions, and in time, the drama group began to receive invitations to tour the various towns.

Personal conflicts that broke out among the actors (on division of the work, etc. – as is common in many theater groups) led to the creation of a new group (die Harpeh), headed by M. Kilikovsky, and Motteh-Leib Kaplan, and this one too, began to present the plays of Goldfaden. The competition was great, and the arguments got more intense, until the actors realized that it would not reflect well on them, and they united anew. The question was: would the united theater group be called HaZamir, or Die Harpeh? Even for this question, an answer was found – they drew lots, and the name HaZamir, came up in the pick…

[Page 41]

An additional step in advancement of the theater took place with the invitation of accomplished actors from Volkovysk, which enabled the presentation of operas. Einhorn describes in his book, that a young Jewish girl from Bialystock, Zavinka, a daughter of poor parents, literally created a storm among the Jews of Volkovysk with her successful performances, with her beauty and sweet voice., An actor named Greenhaus was especially outstanding in the plays of Gordon and Peretz Hirshbein. Despite the difficult condition of the war years (forced labor, hunger, and other constraints), the Jewish theater succeeded in overcoming all its difficulties and it continued to function for a number of years and gave encouragement to the Jewish populace that drew the fullest measures of satisfaction and inspiration from the Jewish theater.

After a while, under the Polish regime, M. Kilikovsky was asked by the Zionist activists to organize a presentation for the benefit of the Zionist Histadrut of the city. He responded to the request, gathered together about thirty young men, and put on the play, Zerubabel. The play was put on in Botvinsky's cinema, and among the cast was Raphael Klatshkin.

After a pause in activity of several years, HaZamir renewed its activities in the late twenties. The director was Yaakov Fisher and productions were presented for: Uriel Acosta, King Lear and various Russian plays that were translated into Yiddish. Presentations were given twice a month, and the revenues were earmarked for various of the city institutions, such as: The Orphanage, Old Age Home, Linat Kholim, etc. Joseph Pikarsky (‘Poliak’) was apparently one of the stars of these performances, and we can see this from the reporting in the Volkovysker Leben in June 27, 1930 prior to his emigration to Cuba..

A Drama Club also existed as part of the HaShomer HaTza'ir chapter, also under the direction of Y. Fisher. Yaakov Einstein was also one of the participants in this group.

It is worth noting that the spark of loyalty shown by the Jews of Volkovysk for drama and theater caused many serious theater groups outside of Volkovysk to include our city in the agenda of their tours, and every artistic presentation was always well received.

Translator's footnote:

- Called ‘Koldunya’ in Russian. Return

Jewish Newspapers in Our City

|

|

The Board of the Volkovysker Leben, with the renown Jewish writer, Z. Segalowitz (1928)

Right to left: Reuven Rutchik, Z. Segalowitz, Mordechai-Leib Kaplan

Standing: Eliezer Kalir, Mordechai Giller |

Two weekly papers appeared in Volkovysk: Volkovysker Leben, and Volkovysker Vochenblatt. By content and appearance, they were not different from many other periodicals of the same kind that appeared in Poland during the twenties and thirties. The standard format was four large pages. The first page was generally dedicated to personal announcements, such as farewell greetings, obituaries and weddings. Theses announcement, naturally, were the principal source of income. The last page was taken up with the calendar of the local community, and commercial notices, and in the inside two pages, one could find articles and writings that reacted to things that took place in the city and in the community, and articles about Jewish subjects in general.

It is worth noting the Volkovysker Leben, in particular, which began to appear in 1925, was in operation for 14 years, and was composed by M.L. Kaplan and Reuven Rutchik. Eliezer Kalir was one of the regular contributors to this weekly, and after he made aliyah to Israel, and settled in Petakh Tikva, he served as a regular correspondent to the paper, and published articles about what was transpiring there. The circulation of the paper was quite limited, and certainly did not exceed 600 copies per edition. In order to meet the budget, the printing shop that produced the paper, also took on other practical jobs, but even this was not a sufficient base on which to predicate its continuity, and various donors from Volkovysk and the United States used to provide support, either large or small through their contributions.

[Page 42]

Reuven Rutchik, one of the editors of the paper, was a truly enlightened individual, having a good command of Hebrew and other languages, serving as a Hebrew teacher in Volkovysk and Bialystock. N. Tzemakh, founder of HaBima, told that Rutchik was his very first Hebrew teacher, who planted the love of Hebrew language in him, and thanks to him, the idea of creating a Hebrew theater troupe occurred to him. Rutchik published his first poetry in the children's periodical, Ben Shakhar, and also published poems and articles in the paper, Der Jude, and other newspapers. The section on humor and satire was the fruit of his pen as well, and to this end, he had a regular column, called Heimishe Inyonim, which was dedicated to jokes, and humorous commentary on the different events in the life of the Volkovysk Jewish community.[1] David Niv told, that members of the Jewish intelligentsia used to meet in the basement of the Volkovysker Leben offices, and they would spend time there doing declamatory readings and interpretations of the works of Virgil, Pushkin, and others, in which each individual attempted to prove his knowledge and familiarity with the classics. The living spirit behind these kind of meeting, of course, was Rutchik. He was killed during the Holocaust, and this was also the fate of M.L. Kaplan, the second editor, and of other participants in the newspaper, such as, Alter Giller (a storekeeper, who while weighing out and selling merchandise, would write poetry, and wonderful songs), Shakhna Dworetsky, A. Tz. Schwartz (a teacher at the Hebrew Gymnasium, who would publish his Yiddish poems in the newspaper columns). Many editions of the local Volkovysk newspapers have been preserved at the national library in Jerusalem, Among them are Volkovysker Vochenblatt, published by M. Ein and R. Shklavin, Volkovysker Stimme, published by Y. Novogrudsky (1927).

Translator's footnote:

- Excerpts that appear at the end of Dr. Einhorn's book have been translated into English, and can be found in the first part of this Trilogy. Return

Volkovysk

In Encyclopedias and Various Historical Sources

|

|

The Executive Committee of HaShomer HaTza'ir in Volkovysk 26 Sivan 5688 (1926),

with A. Moskowitz at the Center |

We find the heading, “Volkovysk” portrayed differently in various encyclopedias and histories. We reproduce two of these here:

The Hebrew Encyclopedia: Volkovysk – a city of the Byelorussian SSR; capital city of the Volkovysk area in the Grodno District; sits on the Rus River (left tributary of the Neman River), approximately 90km east of Bialystock, on the rail line from that city to Minsk. Population 16,500 in 1958.

Volkovysk is found in an area that derives its sustenance mainly from agriculture, raising cattle, and forestry. Most of the production of the area comes from here, and therefore, factories for building materials and metal are found here. Volkovysk already existed in the 11th century. At that time, it served as a fortress to protect the western frontier of the Kievan Rus. After the disintegration of the kingdom of the Kievan Rus in the second half of the 12th century, Volkovysk was captured by the rulers of Volhynia and Lithuania. By the middle of the 13th century, it already belonged to Lithuania, in whose hands – and in the hands of Poland (which united with Lithuania in 1569) – it remained until 1795. In that year, it was annexed into Russia. In 1920, Volkovysk reverted to Poland, but in 1939, it was annexed by Russian yet again.

Jews are first identified in the records of Volkovysk in the report of 1577. In 1766, they were counted in with the community of Volkovysk, which also included the Jews of the surrounding area, amounting to 1,282 people. In 1847, there were 1,429 Jews. In 1897, their number increased to 5,528 people, which represented 532.5% of the population. In the Volkovysk district, there were 18,470 Jews in that year. In 1920, the community numbered 5,130 people (out of a population of 11,000). The community was

[Page 43]

destroyed by the Nazis in the period December 1942-January 1943, with the expulsion of the Jews of Volkovysk to the extermination camps.

Encyclopedia Judaica: Volkovysk – A city in the Grodno District (‘oblast’) in the Byelorussian SSR. Jews are first recorded as residents in the environs of Volkovysk in 1577. There were 1,282 Jews that paid the head tax in 1766 in Volkovysk and its vicinity. Volkovysk became part of Russia in 1795, and in 1797 the population of Jewish and Karaite residents reached 1,477, constituting 64% of the general population.

There were 1,429 Jews in Volkovysk in 1847, 5.455 in 1897 (64% of the population), and 5,310 in 1921(46%). The principal means of livelihood of the Jews in the 19th century were – light manufacturing, crafts, and selling of agricultural produce. Many Jews earned their living by providing various services to the Russian army camp that was based in the area. The Jewish working classes began to organize themselves in 1897, under the influence of the Bund, after a labor strike broke out.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vawkavysk, Belarus

Vawkavysk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Feb 2024 by JH