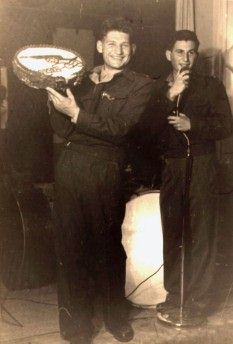

My crew and I visiting Kibbutz Hatzor

At the Misrafa attack during "Horev" operation

This picture is part of "Carmel News Reel"

|

My Russian put me into an artillery unit and I was immediately taken to Pardess Katz where I stayed less than a day. On that same day, they assembled five soldiers for the artillery to fight against tanks in the south. By evening I managed to reach Hatzor where my artillery battery was located. The next morning consisted of four hours of training on twenty millimetre Swiss cannon, HISPANO SUIZZA, and I joined the unit. Our unit was comprised of two young sabres, the commander Eliezer Shleifer and Shmuel Goldberg , two old boys, who served in the British Army and two new immigrants who arrived a few days before me. Compared to them, I knew a bit of Hebrew. The place to where I was taken was the strong hold next to an Arab village Ibdis , not far from Kibbutz Negba which was easily viewed from the trenches. Within a distance of several kilometres was the abandoned Arab village, Beit Affa.

I quickly became part of the detachment. Finally, I was a real soldier and not someone with just a rifle but with artillery. Anyone who came from the Soviet Union understood the importance of artillery. Foot soldiers were called "queen of the battle," but artillery soldiers are the "gods of war." Even though we are talking about one hundred millimetre canon and not the twenty millimetre which looks like a long, thin piece of pipe.

We lived in the trenches during the entire cease-fire period. We did train, but primarily we stood guard duty against any surprise attacks. Once a week we were visited by someone from the battalion to which we belonged, the first anti-tank battalion; they called us the 421st Anti-tank Artillery Battalion. The trench command post was held by the battalion's from the "Giv'ati Brigade. Our gun gave direct support to the front-line unit. From time to time, the front-line unit was replaced, but we stayed in the same place because there simply wasn't anyone to replace us.

Eliezer Shleifer, the detachment commander was reassigned to train new artillery recruits, Shmuel Goldberg was released until he reached his eighteenth birthday inasmuch as he volunteered for the army at the age of sixteen and the decision was made to return the youngsters to the classroom; I was put in charge of the unit.

Commander of a 20 mm anti tank gun crew

As unit commander, I immediately began an educational as well as training program. I requested that a Hebrew teacher be sent to us in the trenches. Apparently, this request made an impression on my battery commander for the next day a volunteer teacher from Rehovot arrived, a very devoted, elderly gentleman who came to teach and train us in the Hebrew language. A week after the lessons began, I requested a record player. I had no specific idea in mind when I made such a strange request; perhaps I remembered the times when we listened to our landlady, Matilda's records. She had one record which contained a recording of LA COMPARSITA on one side and GELOSIE on the other. My teacher seemed annoyed and disappointed with my request, apparently viewing it as unnecessary spoiling. The next day a battalion messenger brought a record player and one record; I remember that one side contained the song, "Yehudim Rachamu Rachemu" ... The teacher was pleased to see the new immigrants, the Gahalnickim, listening to the record and crying because most likely they missed the "shtetl" from which most of us originated. The only record was played again and again at the request of my crew as well of other new immigrants of the strong hold. We all learned the words by heart, which assisted to learn few Hebrew words. Our teacher began to understand my odd request.

There was a fellow named Jimmy from Tel Aviv in my crew. He was already passed the age of thirty and had even fought with the Jewish Brigade during the Second World War against the Germans in Italy. After his return from the war, he worked as a building contractor. He was without any ambition to command and perhaps had never even considered the idea. He loved to tell us how to behave during battle in order not to be killed. He called himself "survivor." He was also extremely proud of very short people like himself, who were born strong and healthy. At the beginning of my tour as commander, a young, decent, handsome and well-built fellow, Shlomo Pulka, joined our crew . He was also a Holocaust survivor who had been born in Poland. We quickly became friends and in my opinion, he was an excellent soldier. I am convinced that if he had not been killed some months later during the Sheik-Noran battle, he would have quickly climbed to the highest ranks of Zahal. He was a quick-study and surpassed his teacher. When we took control of a gun in the battle of Huleikat, I appointed him to be in charge of it and he was a superb commander.

Another young fellow, Ze'ev Weingarten joined our crew. Unlike Shlomo Pulka, he looked for every possible evasive way to get out of the army. He was not afraid; he simply did not again want to be anywhere where his life might be in danger. According to his story, all of his family was destroyed in the Holocaust and as the only remaining remnant of the family, he argued that it was only right that everything possible be done to guard his life. When it was learned that Shmuel Goldberg had been released for being underage, Ze'ev decided that he also was too young because his age, as it appeared on the official list, was incorrect. He struggled for two months until he was given a release from the army, or perhaps he was transferred to a home-front unit. I never saw him again.

My battery commander, Gholovei, had served in the Red Army. He worked within the defence organisation, "Bricha;" this was an organisation which dealt with sneaking refugees into the country. Concurring to what he claimed to be his background, he was conscripted into Zahal and immediately commissioned with the rank of First Lieutenant. He acted as though he were a general, having a personal driver for his powerful, attractive Fargo pick-up truck. Once a week he visited to ask how we were and that was it. He did not care about any military happenings but did concern himself about supplies.

During one of his visits he granted me a few days leave in Tel Aviv where, for the first time, I met my brother who worked in the "Ha-Malchim" foundry as an iron-caster, having learned this profession in Transnistria. I waited until he finished his work-day and then he took me home to his room on Gordon Street in the Montefiori section of town. I gave him all of the cigarettes I had received and the next day he took me to Allenby St. and bought me a pair of shoes with crepe soles, something that was a dream for me. I also went to visit my parents whom I had not seen since our separation in Cyprus on our way to Israel. They lived in the Tcherniavski Hotel located on the main street in Herzlia. Father had found work in a flour mill established in Bnei Brak. Actually, he worked as a technician building the mill with the hope of remaining on as a grinder once the mill became operative.

Immigrant families, who did not want to remain in tin houses or tents in the "ma'abarot," had to find on their own expenses housing. It never occurred to my father to ask the country for anything, unlike the general norm to "Demand" even using different styles of pressure and protest to be given housing, jobs and other commodities. My family was happy with the mere fact that we have been fortunate to survive the holocaust and live as free citizens in our own country.

I returned to my battery and unit in a good mood. I had seen my parents, my father was earning wages and regained his self-confidence which he had lost several times. My brother appeared very tired and exhausted, worked very hard and did not feel good about not wearing a uniform. Everyone was in the army, except for a few whose work, such as arms makers, who were very important to the war effort and they were always at their places of work.

Upon my return to my unit, I was given orders to prepare, with my canon, to join another Giv'ati battalion in preparation for a military operation, which was to take place within the next few days. Our unit set out to capture Huleikat while the rest of the divisions were supposed to capture stronghold 113 and the "Iraq Suidan" police station, later named "Metzudat Yoav". We completed our assignment that same night in a fierce battle causing many casualties in both sides.

The battle for stronghold 113 was cruel, involving hand to hand combat using bayonets. My detachment, dragging the canon, took up the position to prevent reinforcement and afterwards to ward off any counter-attack. With the dawn came the discovery that my unit stood above one of the Huleikat trenches (today it is called Sde Heletz, being the first place in Israel where petrol was found in small quantities). In the trenches we found two abandoned 6-pound anti tank artillery canon and a large supply of ammunition, but both canons lacked their firing pins. According to regulations, when the danger of being captured existed, the firing pins were to be removed in order to incapacitate the weapon. The Egyptians acted in accordance with these regulations but a search of the position revealed not only the weapons but also the reserve firing pins were found in one of the ammo boxes; a few hours later we found the original pins which had been removed and tossed away. We also found a very large supply of armour-piercing shells.

The amount of anti-tank artillery was doubled on the southern front and was incorporated into the era of real artillery began. Concerning the 20 millimetre pieces, there were arguments as to whether or not they were canons or just heavy firing pieces. The original use of the 20 millimetres was against aircraft and army training was for this purpose. They removed the aiming device and attached a platform which allowed one to lie on the ground, maintain a low profile and aim the device very much like a rifle.

We had no idea how to operate and maintain the captured 6 pound anti tank canon. Even Jimmy who bragged about his British army experience didn't know, either. Even so, he was of great help to us. He remembered that our cook Krauss was in Hatzor cooking meals for the 1st lieutenant Gholovei, was an anti-tank artillery man in the British army. We brought the cook, received the necessary training and within six hours after beginning practice we had two new gun detachments.. One was in the hands of Shlomo Pulka and the other remained under my command. The mission in which I participated completed its task and the road to the Negev was open. The capture of the Iraq Suidan police station (Metzudat Yoav) was a mission successfully completed, unfortunately loosing many brave soldiers and officers.

A great deal has been written about the capture of the police station and because I personally did not partake in the battle, I will not go into it here despite having good knowledge concerning the heroics and the failures of what happened. A few days after the mission I received orders to return to Hatzor.

I was advised that my battery commander had been replaced and at the time I was under the same 1st lieutenant Otto Reines (who later became Eitan Ron, Foreign Department ambassador to several countries, among them Japan and Italy). Lieutenant Reines was a different type altogether. He was a good man, considerate and always took an interest in the carrying out of the mission. I was ordered to take my unit, without the canon, and relieve another unit which had spent a long time in the defence of the Negev. This time, I was no longer in charge of an artillery gun; rather it was a half-track with a canon or what is today called "Self Propelled Canon" . It was located in the Beit Chanun orchards in the Gaza Strip, at the outskirts of the city Gaza . During the day we were in the orchard and at night we ambushed the enemy positions in the area for the purpose of improving, inch by inch our positions, in spite of UN strict supervision of the latest cease fire.

This time I was located in an area under the full control of the Palmach brigades. I did get to the Palmach, but as an Israeli army commander and not as part of the Palmach itself.

During one of the night operations the half-track was driven into a boulder, bending the front axle rod which prevented the wheels from meshing with each other. The driver, a short, thin Yemenite surprised me with his ability to drive such a large, heavy vehicle. He explained to me that it was impossible to drive and the front axle rod had to be changed. The company commander, after a thorough investigation of the driver and inspection of the vehicle, was forced to allow us to leave the orchard and drive to Kibbutz Ruchama, the only place in the Negev where there was car repair a workshop.

There were no roads but even though the way had been captured, it was very difficult. It was a rough ride because one wheel did not rotate and kept slipping. In order not to ruin the tire, the driver decided to leave the path for the fields where the ground was softer. Thus, we passed by Nir Am, Kibbutz Dorot until the slow pace of our vehicle stopped altogether. Even our special gear and strong "International" engine in the half-track could not move. When we arrived, we discovered that we had travelled along side the road instead of on it and had dragged all of the communication lines which had been caught in the rear drive shaft. We lost many hours trying to straighten out the tangled mess. By nightfall, because of the high stress put on the engine, our supply of petrol had been consumed.

I decided that I had to reach the workshop at all costs in order to bring a supply of fuel and a tow. Much later, almost nine-thirty in the evening (we started out that morning), a jeep passed us. We stopped it by means of armed threat. The jeep was full of people and various supplies and packages. It was imperative that I reach the workshop and I did not trust them to fulfil their promise to notify someone of our problem. I lay width-wise across the engine cover and after half an hour's ride, arrived at Ruhama.

At Ruhama I found a new world; people were happily singing, drinking and eating. Despite all of my efforts and threats, I could not find one person to help me. They told me that the next morning I could look for the person I needed and anyway, no one would repair the vehicle at night. My disappointment was so immense and burdensome that I promised myself that any unit which I commanded would work both day and night to give the necessary help to those who were engaged in combat missions. From so much anger, fatigue and frustration I simply fell asleep and at dawn continued with my efforts. Close to nine o'clock that morning I left with a tow to bring my friends to Ruhama, who of course thought I was just having a good time. We stayed at Ruhama for two days while they repaired our vehicle. They were two refreshing days. I met girls I never would have found in the places I was posted. It was nice to look at them, hear their laughter, but most of all to smell their fragrance in the air. That was the bravest thing we allowed ourselves in getting close to them.

The battery messenger, riding a motorcycle, found me and delivered me orders to return my unit and the mobile canon to battery headquarters at Hatzor. I asked what would happen to the Palmach Company at Beit Hanun and he replied as I expected - those are battalion orders.

At Hatzor, the battery commander informed me that new artillery canons had been received and I was chosen to learn and then instruct others on how to use them. I was taken to the battalion HQ at Sarafand, today called "Tzrifin." We opened the crates which had arrived by ship, which we later learned was on her way to Egypt. The ship had been sold to both Egypt and us and it was our navy's task to capture her and the cargo. These canons were even older than my 20 mm. They were made by the Italian company Scotti Isotta Frischini. There was only one Italian instruction manual accompanying the shipment. Within a day we succeeded - the artillery ordnance technician and myself - we understood how to assemble and dismantle the canon; the next day we went to the practice range. We discovered that the boxes contained a variety of ammunition and a portion of them were not at all suitable for these canons. Later, we discovered that they were not even identical.

We began to instruct totally untrained groups. I instructed in every language I knew at that point: Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian and Romanian. After two weeks of intensive training where echoes of my instructing capabilities developed during the period in Cyprus as aide to the military school principle in the village Boian, did knowledge of my successes reach the battalion commander; he recommended that I remain as an instructor. However, I requested permission to remain as commander of my fighting unit. In reply to my request to return to my post, they sent me to the Haifa port ordnance depot to help affix 20 mm "Scotti Issotta Frischini" to armoured vehicles.

I was shocked at what they did. In the centre of an armoured vehicle, already having a high centre of gravity, they attached a metal post and were preparing to connect the canon. To my question of why the canon stood so prominently above the edge of the armoured vehicle, I was told that it was because the vehicle was to be used in a hilly area and it was necessary that it have the ability to aim below Zero elevation, that is to say, low angles. Their design demanded that the person directing the canon's aim sit half a meter above the vehicle, a place where no reasonable aimer could feel comfortable. I became involved in an argument with them and managed to convince them to lower the post by half a meter.

That particular armoured vehicle was later assigned to me and with a new crew, I left for the rendezvous point of St. Luke's, which later became one of the most important places in the country; it was the "Gates of Aliyah" at the entrance to Haifa. With the "Oded" Brigade I left on the "Hiram" mission to free the Galilee. The "Oded" Brigade attacked from the western front and the 7th Brigade from the eastern side. The first battle was at Tarshicha. I was given the job of using the canon to snipe at positions as they were found and marked for me. After the capture of Tarshicha with almost no resistance, we quickly advanced to Sassa. On the way, we met the 7th Brigade which had cut the battle-field on its way to meet us. Together with our unit, the battalion continued to clear the Northern Road. Only at the Sassa police station was there a certain resistance. All of the other villages were captured without battle because they surrendered. A white flag stood high on every house. A respectable group of village elders awaited us at the entrance to every village we captured and they signed a letter of surrender. Some of the residents were forced to walk before us and point out any possible mines on the Northern Road. When we reached Kibbutz Eilon in the western Galilee, we knew that all of the Galilee was in our hands.

The entire brigade marched in a victory formation (without any preparation) to Nahariya where we were received as the liberators of the Galilee. In restaurants on both sides of Ha Ga'aton Creek, we were served food and drink at no cost. The Brigade commander to whom I was attached advised me that they were returning to St. Luke's camp and I was to return to Sassa and patrol the Sassa-Safed road until I received other orders. We refuelled, took on a supply of fresh food and some cartons of battle rations and set out on our mission. We patrolled, ate and butchered chickens to give variety to our diet. Our minor supplies (tooth paste, soap and especially cigarettes) had been consumed and my unit, which I met just before the previous mission, was very unhappy about the situation. I, too, had the feeling that they just forgot about us and that our mission was totally unnecessary.

In order not to desert the assignment without orders, I decided to hitch-hike to the artillery base at Jalame, where the Northern Commander of the Artillery was stationed, in order to receive orders .

Arriving at Jalame, I was sent to an officer named Dov Shoshani Rosin. I was told that he was one of the people from Etzel who had joined the Israeli army and that he was a very difficult person. I entered his room and was given a "talking-down" by a voice at the sound and speed of a firing machine. Why hadn't I saluted? Why hadn't I shaved? Plus a long list of questions which were extremely strange to me! After he heard that I had left my unit in order to come to Jalame, he accused me of deserting my troops on the battle-field. He was a "redhead" and his screaming at me caused him to turn lobster red. To his surprise, I did not really argue with him. I exited his room and went to a superior officer about whom I had heard a great deal. I heard that he had been a Red Army Colonel in the artillery. His name was Gorodetski.

I think Gorodetski was a major at that time. He quietly listened to me. I saw that he was not happy with what he heard. He promised to look into my complaint against Dov Rosen Shoshani and if what I said was true, he would make sure that such a thing would not happen again. He gave me supplies for the unit, ordered me to return my unit to Jalame and so that I would not have to carry the supplies given to me, he issued an order that I was to be taken to Sassa in his car and that salaries which had not been paid to my soldiers for three months, at the rate of two lira per month, were to be paid. I never again saw Dov Rosen Shoshani, the officer who was crazy about cleanliness and order, not even throughout the years of reserve duty; it was as though he had disappeared.

By the time I returned with the armoured vehicle and unit to Jalame, orders to return to Sarafand awaited me. At Sarafand I was told that I was being sent to a two-week artillery ordnance course. I was very happy because I wanted to understand how all of the systems worked. I knew that I wouldn't be a ordnance technician and what I would learn would only be used to improve artillery, while this would allow me to instruct people to even a greater depth. Ever since I can remember, I have loved to explain everything technical I know to others. More than once had I invented technical explanations which were almost, but not entirely correct, but in most instances my listeners did not claim that they were illogical.

The course was held at Sheik-Muniss (where today the University of Tel Aviv stands) with short visits to Kiryat Matalon. I really enjoyed the course, especially from the fact that once again I was a student, studying in a classroom and not in the midst of war. I returned to my battalion and not unexpectedly was put in charge of a unit with a 20 mm "Scotti Isotta Frischini" only this time unlike the armoured vehicle which was changed for use in the hilly areas, this one was mounted on a half truck, low profiled, to give protection to the entire crew. Since we were to operate as part of an armoured unit we were given a RT19 communication set, with which I could communicate with the field artillery units as well as with the supported infantry unit.

Now, my unit consisted of slightly more mature personnel. I trained them for several days and tried to convey to them my operation with several days of practice. Meanwhile, I learned to operate other canons during the artillery ordnance course, or more correctly, "canon ordnance technician." The unit was joined by a communication person (today Dr. Ze'ev Katz, Sovietolog), a military photograph/reporter and driver by the name of Yoske Pollack (today owner of the ticket shop, "Rococo" in Dizengoff Centre after he got tired of being a sailor). My group was also joined by an "aspirant" (Acting officer in training) named Boris Diamant, who claimed to have been an officer in the Red Army. He was supposed to be with me in case there was a need to make "more difficult decisions". We were sent south to an area I knew and where I was more comfortable than in the Galilee and where things appeared to be more predictable. In mountainous areas, one could be surprised, without any time to react.

Knowledge of the area and its openness gave one a feeling of security which is necessary for proper behaviour. I was to operate under the orders of Col. Haim Bar-Lev commanded the 9th battalion of the "Negev Brigade" of the Palmach. After one day in the cut-off settlement of Beit Eshel near Be'er Sheva, we joined a festive gathering in Halutza. There, for the first time, we saw the Chizbatron (The entertainment team of the Palmach). With my own eyes I saw Yigal Allon, leader of the Palmach and commander of the southern front. We stood the last formation of the "Horev" operation ,a number of hours later. My first meeting with the enemy was in the trenches of Ath-Mila. That stronghold caused many casualties to the "French Company" (Volunteers coming from France to fight for Israel) who a night earlier tried in vain to capture the stronghold, fiercely defended by the Egyptian soldiers. My armoured half-truck together with a few armoured weapon carriers of the 9th battalion, were arranged to attack first from a semi-prone position and afterwards by concentrated effort on the stronghold. We captured it, my half truck being the first to raid it. Being very eager to find a pistol, I moved around, overthrowing the dead looking for an officer and confiscate his revolver. I found no pistol, but I did find a beautiful winter coat which I took. When Haim Bar-Lev spotted me with my "war trophy" he confiscated it and reprimanded me.

Sometime afterwards we observed a convoy of armoured carriers advancing towards us. We opened fire on them before they came into range, allowed them to come closer and then they fell under our fire power, especially my canon. The Egyptian soldiers abandoned their armoured vehicles which were immediately absorbed into the battalion as soon as we affixed the symbols of the southern command.

After this battle we moved south to recover and reinforce in a temporary bivouac. The armoured company of which I took part, was tasked to continue southwards and combat the retreating Egyptian Army. My half truck had a breakdown, which we could not repair on time to join the company. I was ordered to remain and defend the narrow passage, next to Misrafa and not far from Hirbet El Subeita.

I felt as though I had disappointed my Battalion commander. I took the job of guarding the road very seriously. I issued my soldiers their orders. I divided the area into observation points. A military cameraman/reporter who took part in everything was amongst the crew of our half truck. He apparently had eyes like an eagle and spotted the approach of a vehicle coming from the direction of "Bir Asludge." He said the vehicle was a jeep and I gave the order not to open fire because I wanted to capture the jeep in order to be mobile. I aimed my gun to a spot in front of the jeep where I wanted it to stop without being destroyed. The jeep came to a screeching stop and none other than the well-known Haim Bar-Lev himself, exited. He accused me of opening fire on a road which was already under our control. I was sorry it wasn't an Egyptian vehicle which would rescue me from having to guard the area. He also asked me why I wasn't together with the company; after he received an explanation, he promised to send a carburettor if one could be found.

The urgent business of stopping the jeep passed and I decided to dismantle and clean the canon. The words of Bar-Lev put us into a state of peace despite the pressure first induced of guarding the road. Unit personnel had taken position with their half truck in order to continue taking care of their personal needs. There were even a few who had gone to visit friends and the Chizbatron who together with us were awaiting the solving of a particular problem. Now, I was cleaning my dismantled gun when the aspirant Boris cautioned us that a convoy was quickly approaching. My soldiers wanted to run ahead to meet the formation to hear news from home because the convoy appeared to be a supply convoy. I became suspicious about the identity of the convoy because all of the vehicles were of the same make, same colour and were travelling in too orderly a fashion. This was not true of our army! I detained the group and ordered them into battle formation. Under pressure, I tried to reassemble my canon but without success. Leaving the canon dismantled, I grabbed a Bren gun which I had captured the day before and began to fire on the convoy. The head vehicle managed to escape. It was a command car but the rest of the convoy stopped. The Egyptian soldiers left their vehicles and began to run for their lives in every direction. We returned their fire and whoever managed to survive found his way to Jordan or was given protection by the Negev Bedouins. The convoy vehicles itself remained on the road. It was the last enemy convoy retreating from the supply base of Bir Asludge to escape capture. All other vehicles later using the road were indeed ours. In addition, the Egyptians in the convoy didn't even have time to shoot at us, but even so, they taught us a lesson. Later, after the brief battle was over, I understood that our friends on the cliff-top of the hill overlooking Misrafa wanted to assist us but we were in their line of fire as the road was hidden from their angle of view.

One of our company vehicles arrived in order to tow the Chizbatron to their unit. The driver told us that at Uja El Chafir one of our half-track vehicles, with the motor intact, was damaged by an anti tank shell. We decided to dismantle our carburettor and fed petrol directly from the jerry-can using a piece of rubber tubing. One of the unit's group sat on the wheel fender holding the jerry-can, in fact replacing the carburettor. In this way we safely reached our goal and found the damaged half-track. They helped us to "transplant" the carburettor and once again we were ready for battle. I joined the armoured company and was present at the Chanukkah candle lighting parties in one of the wadis not far from a certain bridge on the way to El Arish. We were to complete our mission by attacking and conquering the Gaza. Due to strong political pressures by the US state department, including threats, Ben-Gurion ordered all troops to quickly return northward. We heard rumours about the argument between Yigal Allon and David Ben-Gurion, who was the commanding officer of the southern front.

We returned to the Misrafa area. On January 3 1949 I received orders to take my self propelled canon and join the Palmach's Fourth Regiment, the "Breakthrough" battalion, under the command of Dado (David El'azar). I joined the regiment, which was already prepared for battle, on the road to Rafiah. I arrived in the middle of a light mortar shelling which was serious enough to stop forward movement of our forces. I was given the task, even before being told of what my job would be in the battalion, of discovering and destroying the firing position. I was chosen for the job because I was an artillery-man, mobile and possessing communication equipment which would allow me to detect and direct our artillery fire to the enemy position. No one asked me if I was part of the regiment's communication system or even if I knew how to direct our artillery fire which was supposed to be in the area.

I left with almost no argument even though I wanted a few answers to reasonable questions such as, for instance, where our borders ended, or to what maximum distance did they want me to fire, etc. I signalled the driver to begin moving and from Ze'ev Katz, our communications man, I requested that he try to make contact the battalion commander or else with some other artillery person. The road which had been built by the British was paved according to the sand dunes. The waviness of the dunes insured that the surface of the road would also be wavy; that is to say, (SINUSOIDAL), with many ups and downs. Spotting was difficult. After progressing several kilometres, with two explosive experts to detect and remove mines from our way, I stopped on the edge of a ridge on the road which I hoped would provide me with an advantageous viewing point. I stood on the roof of the half-track which gave me a slightly better view and with the help of binoculars managed to spot the location of the source of deadly fire aimed against our troops. I am under the impression that I uncovered exactly what I was looking for when at that moment suddenly a number of British "Spitfire" fighter planes, flying very low, attacked us with very accurate gun-fire. The first plane passing over us wounded Yoske, the driver, with a 20 mm bullet and Ze'ev Katz was injured by a splinter. The second plane immediately followed and wounded me, causing me to fall from of the half-track onto the road. The rest of the planes also fired on us. A lot of blood flowed from my head wound and soon I was covered in red. I felt no disturbing pain but was frightened; me, who had survived the ghetto in order to reach the homeland and protect her, was already finishing the job before even doing enough to defended her.

I found out what was happening with my crew mates. The aimer, who had taken cover at the sides of the road, ran to give us first aid. Within a few minutes a jeep from the field command quarters arrived to evacuate me because according to the aimer's observation I had received the most dangerous wound. They were unaware that Yoske the driver also lay injured inside in the driver's seat. I was rushed to battalion headquarters and put into an ambulance without receiving any treatment. Within a few minutes the ambulance was filled with four more injured men, some of them very seriously.

The ambulance began moving but within a minute or two stopped, because the planes coming from the direction of Egypt attacked it. Both the driver and the orderly sitting beside him fled the vehicle to apparently take cover in the sand, we the wounded, could not leave the ambulance and take cover. After the air attack passed, they returned to the ambulance.

We travelled very quickly to the evacuation centre at Uja El Hafir, where later I was spotted by my artillery battalion officer, Rafi Kushneer. Rafi concluded that my condition was very serious because of the way I looked, as did the medical team who decided to evacuate me to Be'er Sheva - in a bus which was used as an ambulance when long distances were to be travelled. We still had not received any treatment, not even bandaging. I tore the contaminated undershirt from my body and bandaged my head. The pain came from my right leg where I saw that I had taken a piece of shrapnel; not particularly big but in there and covered with dried blood. The Be'er Sheva "Field Hospital" also sorted and classified our wounds. There I met a woman orderly whom I knew from Cyprus, the girl friend of one of the Bulgarian Volley-ball players. She calmed me, gave me a proper bandage to replace my undershirt and explained to me that because of my wounds I would be flown to Tel Aviv. I had forgotten about my wounds and the pain which had increased because I became excited about the idea of flying. It would be the first time I had ever flown. The plane was a Dragon Rapid, a small short haul passenger air-plane seating six . In Tel Aviv we were placed in an ambulance for the seriously wounded and taken to Tel Litvinski (Tel Hashomer today). In the hospital my contaminated, blood-soaked and dusty clothes were removed; my head was washed and it was determined that I had not suffered a head injury from any foreign object; rather, the injury was caused when I fell from the half-track after being hit in the leg by shrapnel and struck my head either on the vehicle or on the road when I landed. The leg injury was much more serious but a pair of forceps soon took care of that problem. The doctor who took care of me became angry and gave me hell because a person with my injuries should not have taken a space on an aeroplane that is used only to evacuate the seriously injured. He refused to even listen to my attempted explanation that I didn't evacuate myself. Despite his berating, he gave orders to detain me for two days of treatment and afterwards I was to rest a week in rest home number one, not far from the hospital.

After one day in the rest home I requested permission to recuperate at home. My request was granted and I was given the necessary permit. I arrived home with a slight limp. My head wound quickly closed and left a minor scar. My leg wound was deeper and light touching on the bone. I felt better each day. In my parents small and crowded hotel room, there was always room for the children; generally, we always had room because if it was what we wanted, then there was no problem.

A number of other new immigrant families also lived in the hotel; in the room next to ours lived a family with a sixteen year old daughter named Ida . My mother was very fond of her and apparently told her stories of wonders and miracles about me. The girl came to visit me twice a day and we became real friends. She was not particularly beautiful, but neither was she ugly. She was very alert and loved to talk, but even more, she loved to listen. I told her about the war, our victories and horrors. She moved closer and closer to me and one evening invited me to her room where I discovered that we were alone. Maintaining a proper "distance," our bodies shivered when we accidentally came into contact with each other and found the courage to kiss. We both agreed to do so at every opportunity when we met again. In Herzlia there was a photographer, one of my mother's friends and Ida convinced me to have my picture taken so at least she would have a photo of me.

I returned to the rest home for a check up. They decided that I was fit and gave me orders to return to my battalion at Sarafand. Reaching the battalion area, I came face to face with the battalion sergeant major, Stern, the same fellow I knew from the time I was an instructor. He recognised me but did not react. After taking several steps, he stood back on his heels and asked if it was indeed me and said hello Fichman. When I replied in the positive, he took my arm and pulled me to the office of the battalion commander, Daniel Kimche and the assistant commander, Yehuda Fundiler. I tried to explain to him that I had a permit and had not gone AWOL because he kept shouting at me, "Where were you?" In the office, the commander rescued me from the sergeant major. The former had received a report that I had been seriously injured and evacuated. Their investigation of the event revealed that I had been flown to the hospital at Tel Litvinski and when someone came to enquire about me at the hospital, they were told that "he is no longer with us!" (Interpreted to mean that I was dead.)

With the same seriousness, after the error was clarified, they asked me what I wanted to do once I would be fully recovered. I answered that I would like to be a radar technician. They didn't really know what I was talking about as even I had found out about the subject by myself. During the time when I was an instructor, I visited Tel Nof in order to meet with other instructors of anti-aircraft defences using a 20 mm artillery piece. There, my instructor was Abby Mackless who would become a lawyer and head of the Savyon local council. At Tel-Nof I met a relative of ours, Rachel Shechter. She was in the United States before the Israel's Declaration of Independence and under the influence of the Haganah she learned to be a radar operator. She told me about herself and about the wonder produced by technology, an instrument which could spot and follow planes at a distance of tens of kilometres and all of this using radio waves.

After explaining my request to them, I forgot about it. I remained for a time at headquarters and kept busy with the collection and storage of anti-tank ammunition which had been abandoned and captured from our enemies.

We separated the crates and recorded everything so that we could remove them for use and know at all times what was still in stock.

This was the biggest organisation job I had done to date as well as being the largest number of persons under my responsibility. Actually, I assisted a senior and very experienced sergeant who apparently realised that he had in his hand a soldier with initiative and energy and he let me get on with the job, so long as I kept him in the picture and consulted with him as needed.

My job with the ammunition finished. Again, by order, I was given a job as a commander. This time, I received a company consisting of two 6-pound pieces of artillery from the captured supplies we took in battles at Iraq Suidan at strongholds 113 and Huleikat.

After the "Uvda" campaign and capture of Eilat, I think the war ended and there was talk about being released from the army. Despite all of the talk about the war being over, I received orders to leave with the company and go to an artillery army camp near Kfar Yona in the Beit Lid area. Upon my arrival at the camp, I received orders to set the artillery opposite the village of Tulkarm. We left to prepare our positions, place the artillery and were ready. The goal of the campaign, the last planned for the War of Independence, was to secure the border and widen the bottleneck in the narrow Netanya region. Because of international pressure or perhaps other reasons, the orders were cancelled and we returned to the artillery base.

My crew and I visiting Kibbutz Hatzor

At the Misrafa attack during "Horev" operation

This picture is part of "Carmel News Reel"

Several days after the cancellation of the operation, I was summoned to the Battery office. The Battery clerk handed me an official army paper, ordering me to present myself immediately at an Air Force unit to participate in a detachment commanders course.

I revolted instinctively asking why at the end of the war, after being a detachment commander for almost 9 months, part of them in battle, do I need a detachment commanders course. The clerk had no satisfying reply, using only the well known army explanation “those are orders and you must follow them”.

I choose one of my best soldiers, appointed him detachment commander, gathered my belongings and left for the Air Force unit. Something didn't fit. Why in the Air Force, and why so suddenly was I removed from my command? I felt no guilt and had no thoughts that to command a detachment I need any further training. The only explanation was that I was a new immigrant, at a too high command level. The feeling of being odd, a new comer in the ranks of command was not new, but I never explicitly was thinking about it. This was the first time.

The Battery service car brought me to the new destination in Sarafand, one of the largest, former British, military bases, The 505 Air Force Squadron.

Here I learned that the clerk of my battery misunderstood the Hebrew acronym (MAKAM) for RADAR thinking it was (MAKIM) the acronym for detachment commander. The enigma was solved and I was happy, because it was my request to acquire a profession which may be useful after the war. I handed my papers to the squadron clerk and he gave me a red card. My suspicion arose again because all the others received a blue card.

When I protested against discrimination, because I was the only new immigrant among the candidates, the clerk explained that I was the only sergeant while the others were just privates. The rank was a real and happy surprise. I knew I was a detachment commander, but nobody ever told me that I was promoted . The clerk also took care to reimburse me giving me a considerable back pay for all the months I received pay as a private. I was very content that there was no discrimination, but in my own mind, and that fairness is part of the culture and regulations. It took time and effort to get rid of the suspicion of being persecuted and discriminated.

As a new born sergeant with stripes on the right sleeve I proudly walked around, glancing from time to time if it is still there and how the others react. It was good to be rewarded for the very hard work and great responsibility I exercised for so many months part of it under enemy fire. I had no problems of being absorbed. The army was and I believe still is the best absorption place in the country, but it was here, perhaps for the first time, that I began to feel integrated as well.

Since I was born, in spite of belonging to a wealthy family, never have I enjoyed the luxury of my own and separate room, except maybe the tent in Cyprus. Being a sergeant I was given the privilege of sharing a room with no one but myself. It was a something worth celebrating and I wished my parents especially my mother could enjoy seeing me in such a nice room of a former British officer.

This was the first RADAR technicians course, which opened officially on March 1949 and ended December 1949. About ten students part of them from the artillery but the majority young high school graduates. Among the students I will mention but few: Arie Kaplan , Shlomo Hatzav, Shlomo Hai, Zahavi, Unikovski and Ya'akov Ziv.

(Professor Ya'akov Ziv became famous the world over for his scientific achievments in telecommunication). I have got the idea of becoming a RADAR technician from my cousin Rachel Schachter whom I visited in Tel-Nof where I attended a refreshment course in anti aircraft artillery. She was a RADAR operator who explained to me the basic idea of RADAR. I was fascinated by the technology, and at one of the opportunities discussing with my Battalion commander I requested if possible, when the war ends, to send me to such a course. I am forever grateful to Rachel and very obliged to my battalion commander not forgetting my request. I learned a lot from his gesture.

Our teachers were the Gategnio brothers, Mr. Sam Levine, (now a professor at NYU ?) a volunteer from the USA, Ing. Acker and others. The squadron was established by a professor at the Weizman Institute and during my stay it was commanded by Charlie Broide, a South African scientist.

The course was conducted in Hebrew and in English. All the books and technical material were in English. The main book, which became the bible for many generations of many RADAR engineers and technicians, was the MIT world war two edition “The Principles of Radar”.

It was difficult for me both the learning material and the English language, but I was determined to overcome all the obstacles. I worked with dedication and had a very high level of motivation which helped to overcome part of the many education deficiencies I had.

For me the course was quite intensive, because in parallel with the regular curriculum I had to complement it with private lessons from who ever was willing to teach me, on every subject, such as English, Physics, math. Etc. I wasted no time. All was dedicated to learning.

Most of the students had well established homes, they could travel in the evenings after school hours to town. My parents lived in one room at the Cherniavsky hotel in Herzlia, it would have taken all the time I could dedicate to learn and improve my chances to successfully resolve and become a licensed RADAR technician. At the last part of the course, a decision was made to start volunteering for the regular army service. Nobody knew what it meant and a great deal of advertisement urged us to join, in particular professionals like Radar technicians. I needed no effort to convince me. I loved the idea and joined immediately the regular army where I served for 32 years

In parallel with the technicians course several consecutive RADAR operators courses were held, all female. My friends dedicated time courting, I was busy learning, but not only because my total dedication for achievements. I was also very shy and inexperienced with girls of my own age.

After graduation we were appointed to serve as technicians at the various RADAR stations. I was sent to the Giv'at Olga Radar Station, located in a former British Police station on the Mediterranean shores.

This was my first period of rest and relaxation but also a period of reflection. At the Radar station we were a small family, the Commander who came to visit from time to time spending only few hours each time, two radar technicians, one experienced and myself, four Radar operators per shift and a driver. The operators used to leave post for home after their shift was over, the others stayed permanently at the station. We used to have lunch and dinner at Moshe Sinai's restaurant in Hadera, the nearest town. The driver was the most important person , taking the girls home and all of us to the restaurant. He was our main contact with the rest of the world and was very popular with the girls who liked him.

At the station there was a huge radio set, having excellent acoustics. I loved listening to music, particularly Vibraphone recordings, new to me. The tunes of the late forties were melodious and their content romantic, with which I identified.

One of the operators, Batya Abitboul, whom I met at the squadron while she was at the operators course, was also stationed at Giv'at Olga and the only one who noticed me, perhaps out of curiosity and being the only new immigrant, a holocaust survivor. She was very nice to me and we maintained friendship relations for many years. I liked being with her and her family belonging to the Sephardic elite of Haifa. I did not understand at the time that an immigrant from Rumania, a holocaust survivor with no profession or economic status is not fit for a daughter of such a family.

My brother David on the Haifa promenade

Sergeants David and Shalom at the promenade

Artillery Officers Course

After three months of a kind of a vacation at the radar station I was ordered to present myself for an interview at the Artillery Head Quarters in Sarafand.

After becoming a regular army volunteer I was transferred to the Air Force. The order to present myself at the Artillery HQ was a surprise. I had no idea what was the purpose, but orders are orders.

At the HQ I was met by my former deputy CO at the First Anti Tank Battalion, LtCol Fundiler. He had a very warm smile, he looked at me and embraced me , telling me that it was he who remembered my request to become a Radar technician. He told me that he followed with satisfaction my progress although at the time he had to defend my basic competence for such a demanding course. He made the effort due to my excellent operational and training performances during the war. I was proud hearing his revelations. He then introduced me to the Commander of the Artillery, Colonel Meir Ilan who asked me to return to the Artillery and become an officer. He informed me that the IDF is acquiring a regiment of Anti Aircraft weapon systems, all computer and Radar controlled. That, he claimed was the basic reason why I was sent to get familiar with Radar technology. He seemingly was not coordinated with LtCol Fundiler in this regard.

It was my first encounter with such a high ranking officer and was in no condition to negotiate. My only question was to enquire whether the Air Force would approve my transfer. He replied that it was already been taken care of. A paper was put in front of me and asked to sign it, which reluctantly I did. I wanted to think it over, discuss it with my friends, but they urged me to do it fast because I am already late for the acceptance tests.

I returned to my station, gathered my few things, bade farewell to my colleagues and hurried back to the Artillery school. For three long days we were tested. Following my service at the station I was far from my best physical condition, but I was nevertheless accepted for the Officers "training course"

We numbered 120 officer cadets and formed three groups of forty . Each had a commander. and mine was a former Artillery officer in the Italian Army the others were officers who got their artillery education in the British army or participated at the previous Artillery Officers course, a year before.

The training and education was intense and the discipline was extreme. The school staff wanted to create an Israeli Artillery officer who is intelligent, polite and very disciplined.

The course had three main parts each lasting three months. During but mainly at the end of each part, many of our colleagues have been expelled due to poor performance and discipline. At the end of the course only 54 of us remained. No one even to the last day was certain of graduation. They kept the pressure constant and continuous. I was one of the lucky survivors.

There was a parade on December the 20th, 1950, before our Chief of Staff, Lt. General Ygael Yadin who witnessed and approved our graduation promotion.

My parents as well as of the other graduates attended the ceremony. My mother, as always was proud, happy, but crying aloud with tears like a torrential rain pouring from her red eyes. There was no greater joy in her life since our liberation from the Nazis. She cried remembering, not forgetting our family who were deported to Siberia and who perished in the various camps of hunger or diseases. She was very proud but sad remembering how we many times almost lost our lives. She was proud and happy that her last born child has fulfilled his dream to become a soldier in the Jewish army in Israel.

Her youngest son is an Artillery officer of the army which overcame victoriously, the attacks of regularArab expeditionary forces. My father was just proud, I could see this in every of his 613 parts of his body. They both hugged and kissed me because we felt happy, not as we did during the Holocaust, to make a vow “To Survive and Tell”.

Cadet Officers on a weekend trip home by train

I stand third from the right

The cadet visiting my friends

at the Mount Carmel Radar Station

I am between two Radar operators

Amnon Rubinstein and myself,

selling a cake to cover the

expenses of the graduation party

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

"Survive and Tell"

"Survive and Tell"

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 11 Jun 2005 by LA