|

(The articles by Mordechai Zeitchik and Avraham–Yitzhak Slotzki, pp. 309, 312)

|

|

[Page 305]

|

|

(The articles by Mordechai Zeitchik and Avraham–Yitzhak Slotzki, pp. 309, 312) |

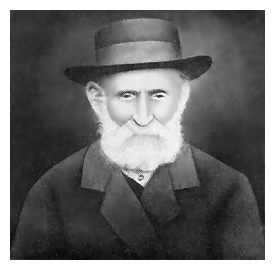

Mordechai Zeitchik

Translation by Yocheved Klausner

The Old Synagogue

The Old Synagogue was built around 1870. Before that, a small synagogue stood on the same plot of land.

The new shul [synagogue] was built around the old one, on all four sides, without touching it, and the prayers were held regularly until the new building was completed. Only then was the old little shul torn down.

The new building (still called, of course, “The old Shul”) was tall and was built from the best wood, acquired at a reasonable price from the owner of the forests, the Graf Witgenstein.

Most of the expenses of the work and the additional material needed, until completion, were met by the Gevir [rich man] of the town at that time, R' Mordechai Tziklik, son of Mendel.

The synagogue had many seats, a large Bimah with additional seats around it, a beautifully carved Ark for the Torah Scrolls, etc.

The women's section was situated on the second floor, with a view to the men's section. There was also a small room for an extra minyan [prayer service, lit. prayer quorum of 10 men], mostly for those who came in late.

The people who prayed in the synagogue itself were of the old and well–situated families in town. The rabbi and the cantor had their own permanent seats in the South–Eastern, honored corner of the synagogue.

Most of the other people who prayed in the shul were plain laborers of the lower classes, amcha – “Simple Jews.”

As mentioned, the synagogue was large, especially in relation to the town itself, and occupied an area of 400 square meters.

In later years, the long beams that supported the ceiling began to bend, and they were strengthened by four wide columns.

The Bimah and the Ark were quite beautiful, but not too luxurious.

The synagogue also served as the place where various disputes and quarrels between members were resolved, not excluding even fights and slaps on the face – and to make it worse, even on Shabat… and when? during the reading of the Torah. The reasons of the fights were often petty and trivial, even foolish.

[Page 308]

Various festivities, in honor of the Russian, and later the Polish holidays were held in the synagogue as well.

Clearly, the various preachers delivered their sermons in the Shul. Also, only here could one say his prayers with all his heart and soul. Only in the Old Shul could one feel the meaning of truly “pouring out one's soul.”

No one was ashamed to pray from the depth of his heart and burst into tears for as long as he wanted.

Always, at any hour of the day one could find here a man sitting with his Talit and Tefilin [in prayer, lit. with prayer–shawl and phylacteries], or learning a “page of the Talmud” [daf Gemara], or simply read from a book.

The New Shul

The New Shul was much younger than the Old one – was built later, in 1900–1904. It was located at the beginning of the Parlipie Street, on the left side.

It was much smaller than the Old Shul, but much more beautiful. It can be truthfully said that it was a very beautiful Shul. The walls and the ceiling were artfully painted and the Torah Ark was a masterpiece of carved branches and fruits, which stared at us as if they were real.

This was where the Lenin intelligentsia prayed, the well–to–do house owners [Balebatim] and the sons–in–law who had come from other towns and shtetlach.

Old, established Lenin families were few in that shul. Here, one felt a little more free. In the near–by shtiebel, actual politics was analyzed and discussed constantly…

On Friday nights, especially in the winter, when the evenings were long, outside was cold and inside the shul pleasant warmth was spreading from the little stoves around the bimah, people would gather after the Shabat dinner to listen to the Weekly Portion of the Torah.

The rabbi was the teacher, and all kinds of people would sit around the table and listen: learned Jews and simple Jews, who loved to listen to the beautiful stories, in particular from the books of Genesis and Exodus.

This was not simple and superficial learning of the Torah Portion; it comprised profound discussions about the various commentators, legends, wise sayings of the great scholars through the generations, etc.

The members of the congregation loved to come to these lessons and really enjoyed them.

[Page 309]

At the same time, the younger boys and some of the 14–15 year old boys would sit together around the warm stoves, in half darkness, and listen to various mystery and miracle stories, told by the older lads: about devils, robbers, jokers, heroes from Russian tales, as Ilya Murametz, Elyosha Popovici and others.

The young listeners would sit close to one another, fearing to make a move and listen breathlessly to the stories that the older boys told.

And, at times of distress, people would come running to the old or the new synagogue. The Holy Ark with its Torah Scrolls, more than once listened and absorbed the anguish and weeping of the women, who came the “cry out” for illness, suffering or persecution…

Mordechai Zeitchik

Translation by Yocheved Klausner

We do not have any information about the first rabbi in our shtetl. It is only known, that a rabbi was officiating in Lenin during the years 1830–1860. He was probably one of the first, since before that the number of Jews was too small to afford a rabbi. The slaughterer in town performed the functions of a Rabbi as well.

The history of the rabbis in Lenin begins with the arrival of the rabbi R'Yehuda Turetzki, about 1860. A detailed discussion should be devoted to this rabbi, for several reasons: first, he served as rabbi in the shtetl for over 66 years; second, because of his personality and exceptional qualities as a person.

Rabbi Yehuda devoted all his time – day and night, at the shul and at his home – to studying Torah, make Halakhic decisions, resolving arguments, marrying bride–and–groom, etc. He distanced himself from worldly affairs, did not know even one word of the Russian language.

He was a wise Jew, sometimes left the impression of being a strict, even angry person.

He was the student of famous great scholars from the old generation and a friend of the “Chafetz Chayim” and several other great rabbis.

Almost all his years he lived in poverty, only during the last few years his situation improved a little. The reason was not that the town could not afford to support him; in those times it was taken for granted that a

[Page 310]

Rabbi should lead a modest life, as it is written [in Pirkei Avot – Wisdom of the Fathers]: “Bread and salt should you eat”…

The rabbi made his living “from the ‘karabke’” [“from the tax–box”], that is, from the “concession” to sell candles for Shabat, sell yeast, recite the Yizkor prayer [memorial prayer for the dead], sell the Hametz [leavened food] before Passover, as well as from various small payments and gifts from the rich and well–to–do.

The rabbi was much loved not only by Jews, but by the municipal authorities and by the surrounding Christians as well. In particular was he loved by the priest, who would visit him often, especially when he was ill; they would sit for hours and talk, with the help of an interpreter.

The Christians had great respect for the rabbi, although he was very seldom seen in the street. They regarded him as a holy man.

As mentioned, he was almost always sitting by the open Gemara [Talmud] or another book; his custom was also to pace through the room back and forth, with small quick steps, thinking of what he was studying at the time.

When a Jew would bother him too long with trivial questions or discussion, he would say to him: “Well, a good night to you” and gave him his hand, as if saying: “Go home in good health, R'Jew”…

His room was never empty – with every small matter the Jew would go to the rabbi; all the disputes and worries he would bring to the rabbi; no court of justice was held in greater respect.

He lived in town, as mentioned, 66 years, and died at the age of 96 years.

Perhaps he would have lived even longer, had he not broken a leg. One day the rabbi stumbled and fell, and his leg broke. They brought for him the famous surgeon from Minsk, Dr. Yevseyenka, who operated on the leg and did what he could regardless of the age of the rabbi, and the leg began to heal. But as fate would have it, he soon broke the same leg again, and this time it was necessary to amputate. This difficult surgery was too much for him and he passed away.

It is hard to describe the mourning of the entire town after the death of the old and beloved rabbi. The Lenin Jews mourned for a long, long time and could not forget their great Tzadik.

Famous rabbis from the surrounding towns and shtetlach came to the funeral, with eulogies by R'Itchele, the Lachover rabbi, R'Valkin the rabbi from Pinsk and others.

R'Yehuda Turetzki had 4 sons and 3 daughters – all talented and learned: R'Itche, R'Aba, R'Shmuel–Mechl, R'Moshe, Sheindl, Ete and Bashe.

R'Itche died young, of a snake bite in the forest;

[Page 311]

R'Moshe was rabbi in London; R'Shmuel–Mechl was rabbi in Pinsk and was called “the Karliner dayan” [dayan = judge in the religious court]. He was a Jew with a silken soul, a great learner and very erudite. He published a book dedicated to his father, which contained a collection of sermons, commentaries and “good words” [sayings, explanations]. The daughter Eta lived in Pyotrikov; Bashe and her husband R'Yakov the slaughterer lived at first in Lenin where they had a grocery, and later in Minsk; Sheindl and her husband R'Hillel lived in Kazhanhorodek.

After the rabbi's death, R'Nachman Wasserman was appointed rabbi. He was a wise and worldly Jew, good looking and friendly. His home was always full of people, who came mostly to ask for advice. He was a gifted speaker. The shul was full when he delivered his Shabat sermon. He was a Zionist. But he did not stay long in Lenin, for he was appointed as rabbi in the shtetl Stavisk, near Lomzhe.

After R'Nachman Wasserman left it was not easy to choose a new rabbi. More than six months passed, and the shtetl could not find a suitable rabbi. There were two “camps” that couldn't come to an agreement: when one candidate was accepted by one camp, the other camp was against, and vice–versa…

Still there was one thing that the entire shtetl enjoyed during all that time: The congregation heard speeches and sermons from all types of rabbis: young and old, with black, yellow and red beards, and some even without a beard at all. Every member of the community could almost become a rabbi himself…

Fridays and Saturdays, sometimes even during week days, the synagogues were full of men, women and children, who came to hear the sermons. It looked as if everybody left their work only to come and see the rabbis, how they looked and how they spoke, in order to decide who would be the best candidate and should stay in town. Obviously, each candidate made every effort to show his best side, until the people became utterly confused… Finally, they chose as rabbi R'Moishele Millstein, or R'Moishele “Warshaver” – a young rabbi, a known Illuy [genius] and good looking; he was also a maskil [enlightened], that is he knew several languages and was involved in general issues. He had 5 children, all of them beautiful. Had a pleasant voice for learning and prayer… He had lived for some time under German rule; they harassed him and he suffered much, as is described in the previous

[Page 312]

chapter. He served as rabbi in our shtetl for about 12 – 13 years. During the worst times and the critical moments of the Nazi occupation, he would say that that he was certain that the Germans will lose the war and Hitlerism will succumb. He would say that he has proof. He was knowledgeable in world politics; he was interested in all subjects. He was the last rabbi in Lenin. He perished by the bestial Nazi murderers, together with the other Jews, on 14 August 1942.

Avraham–Yitzhak Slutzki (The United States)

This rabbi was of the old type of small–town rabbis, a wise Jew, very modest. Not a big entrepreneur and not a brilliant speaker. He was, however, a great learner and not a fanatic. But he did not have the qualities necessary to lead the life of the community. His apartment as well as the room where he conducted his court were in a house that belonged to the community, located in back of the Old Shul. He was very poor, and I remember a wedding in a rich family, where all the important people of the town were invited. At such a wedding the cantor would come, with his choir, and sing for the guests and the prominent family. At the time of the dinner, when all were sitting at the tables, the rabbi rose and addressed himself to the important balebatim, telling them that he was so poor that he couldn't afford to buy a wagon of firewood to keep his house warm during the winter. At the time he made his living by selling yeast for two Kopeks to the housewives, to make Challa for Shabat. Obviously this could not be called “to make a living.”

From then on, discussions in the matter began in the community, and after several meetings it was decided that the rabbi shall receive a raise, and instead of 2 Kopeks they will pay him 3. In addition, it was decided that the groceries will not be allowed to sell candles for Shabat, and the entire candle business shall be handled by the rabbi. After many unpleasant discussions with the grocers, the candle business was given to the rabbi, and more light and warmth spread in his home.

Mordechai Zeitchik

Translation by Yocheved Klausner

A cantor, in a shtetl like Lenin, had to be a slaughterer and a Mohel [circumciser] as well. But the main function was that of the cantor, and it concerned, obviously, music. The cantor was required to be knowledgeable in music, even if he did not have a very beautiful voice. It was very important that he be able to recite his part of the prayers accompanied by a choir, so that the congregation could enjoy a “good piece” that would really touch the hearts…

The cantor was not necessarily required to be able to reach “the high C”, but he needed to have a pleasant voice and pray from the heart.

He was helped by the choir on regular holidays, on the High Holidays [Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur] as well as on the first days of Selichot [“prayers of forgiveness” on the week before the Jewish New Year] – one day in the Old Shul and the next day in the New Shul.

On Yom Kippur the arrangement was: Kol Nidrei in the New Shul, next day in the old Shul. Every year he would bring some new melody.

We, in Lenin, could hardly imagine that in other shtetlach the prayers were held without a choir. How could that be?? How would that feel?

The cantor was paid a salary. For the prayers on holidays, when he had a choir, he received an extra bonus. He was in charge of assembling the choir every year. The choir was a great help: the cantor could rest while they were singing or when they held “a long note.” On Yom Kippur, at the time of the “kneeling” [kor'im] the cantor was already so weak that two of the choir members had to help him stand up…

The congregation in the Old Shul was most eager to hear the singing of the cantor and his choir. They were even more attached to the music than the people in the New Shul, and many would go to the New Shul, to hear again the “concert”….

And now some history:

The first cantor and slaughterer in Lenin, years ago, was R'Leibke; later came R'Hershel Hoskowitz, who was a melamed [Torah teacher of young children] as well, because in those times it was not possible to earn a living as a cantor and slaughterer alone.

Later still, the cantor was R'Israel Chaim. After him there was no “professional” cantor for a stretch of time, but there were several good Baalei Tefila [performing the function of cantors, lit. “prayer–people”] in Lenin, for example R'Chaim Berl Migdalowitz. For some time the prayers were conducted by the cantor Yakov Shmuel, who considered himself a Lenin man. He prayed very pleasantly.

From him we remember the special melody of Ki hem chayenu in the evening prayer [ma'ariv], [Page 314]

|

|

a very beautiful melody, which was adopted for many years by other cantors as well.

The cantor Leibl Gershon caused a real sensation. He came for a trial period with a choir, which included a limping baritone, an alto, a handsome soloist, who always wore a scarf around his neck and others.

The cantor and his choir were a great success; it was a real choir, and they sang using a real musical score, like in the big city. The trial period was successful and he remained in the shtetl as cantor and slaughterer. From the choir he kept only the alto.

The cantor, a tenor with a blond–yellow little beard, was fat and strong (at the slaughtering house, he would throw down the heaviest ox with one move). He came from Minsk at the beginning of WWI and served in town 5–6 years. From his famous prayers, which were continuously repeated in town, it is worth mentioning: Kevakarat ro'eh edro, Vayehi Vayom Hashlishi and others.

After him, the community hired as cantor and slaughterer R'Feivel Chinitch, who came from Starabin – Slutzk.

He was a “beautiful Jew” [a Sheiner Yid], with a dignified look and a thick black beard. He was also a scholar, and liked to learn. He was a good musician, although without a musically educated cantor–voice, but his prayers came from the depth of his heart. He also had a choir. The prayer that was remembered from him was, in particular, the Kadish said after the Ne'ila prayer [the prayer that concludes the Yom Kippur service] – a special, joyful melody, which erased in one stroke the difficult

|

|

[Page 315]

day of fasting, together with the sins… The entire congregation would join the singing…

After him the cantor and slaughterer was R'Moshe Novik, who came from the small shtetl Snow near Baranovitch. With all the others he was sent by the Germans to the concentration camp in Hantzewitch, later fought with the partisans and lives now in Eretz Israel.

Sextons [shamash] and Assistant–Sextons

Since a shamash in a shul, especially in Lenin, received a very low salary, never enough to feed his wife and children – he was forced to take on additional work, as learning Gemara [Talmud] with the older boys etc. In addition, the functions of a shamash included such minor seasonal work as the customary “flagellation” on the eve of Yom Kippur and others. All in all, the sexton could never become a rich man…

Lenin had various types of sextons. Below we shall tell the story of the most interesting among them.

In the Old Shul, there was an assistant–sexton by the name of Tolye Kanik, who was always busy, either sweeping the floor of the big shul, or carrying water, or chopping firewood to heat the shul.

He was a short man. When he was hired for his post he was quite young, and he didn't know Yiddish, that is, he did know the language but he pronounced only half of each word and one had to make an effort to understand what he meant. Later, as people got used to his speech, they almost understood him. He would say that he “got this from the war”; he was a “soldier” and was still suffering from the wounds…

He was a good worker: even in the greatest frost he would cut the thick, heavy pine logs to prepare them for firewood.

Children were always looking at him, how he was dragging the heavy firewood into the cellar of the shul, to place them in the stove in order to keep the fire going and the entire shul pleasantly warm. He was a quiet man, but when the children would tease him and take one of his tools, it was terrible.

His wife was even shorter than he, a fat Jewess, almost round, with black shiny hair… They were a strange couple. It was interesting to see how they would sit and talk, on the stone bench in front of the house. They were like a pair of loving doves… but when she spoke, her voice was heard as far as two streets away… Those serious discussions would take place mostly on Sabbath eve, and they concerned the

[Page 316]

fact that soon the Holy Sabbath is beginning and they still had nothing: Challah [Sabbath bread], fish, meat…

Once, on a frosty winter day, the wife of the sexton, Alte (that was her name), while going to the well to get water, slipped on the heavy ice that formed every winter around the well. She fell and rolled down into the well, which was about 8–10 meters deep.

By a miracle she was not hurt much, but as she was round and plump she filled exactly the size of the well and was stuck, sitting in the cold water… Finally, after great efforts, they pulled her out of there.

In his older years, Tolye complained of pain in the ears and the head, and several years later he died.

|

|

We can see the Ohel (lit. tent: a structure built over the grave of a Tzadik or another prominent person) over the grave of the rabbi R'Yehuda Turetzki |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lenin, Belarus

Lenin, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Jan 2017 by JH