Post-War Jewish Kopaigorod

No matter where life takes you, if you hear, “What, can't wait? Is it already burning?”, or “VUS? A but brent?” (What? The bathhouse is on fire?) you know that you have met a resident of Kopaigorod.

The Jewish way of life was preserved in Kopaigorod almost until the 1960's even though the situation of the Jewish communities of the Vinnytsia region in this period was generally determined by the anti-religious policy of the Soviet government. There were several factors that gradually suspended the religious life of the Jews in the Soviet Union. Jews could not fully resume their religious activities after the fascist genocide. In the postwar period, the concept of a “Jewish town” was actually destroyed as a kind of social phenomenon where national traditions and customs were passed down from generation to generation and the peculiarities of religious life were preserved. Jews actively experienced a period of urbanization as they migrated from villages and small towns to the big cities of the USSR. Jews gradually became less religious, or even atheists, as a result of their high level of education and new areas of employment. That some religious life still existed in small towns was an exception to the general rule.

There were still a significant number of Jews living in Kopaigorod at that time. They were doctors, teachers, trade and communication workers, engineers, and simple workers. According to statistical data, 504 Jews lived in Kopaigorod in January 1959.

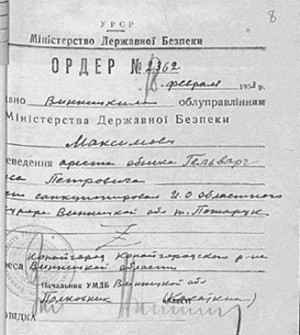

The chief doctor at that time was Borys Petrovych Gelvarg, a Jew, and a veteran of the Second World War. He was an intelligent doctor and organizer. During the era of the Doctor's Plot, he was arrested on February 14, 1953 and accused according to Art. 54-1 “b” of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR. Many Soviet doctors, particularly those of Jewish descent were arrested between 1951 and 1953 on the trumped-up charge initiated by Stalin, that the doctors were planning to assassinate top leaders of the Communist Party and the USSR. This was accompanied by an explosion of anti-Semitic activity in the Soviet Union. Gelvarg's case was closed on June 10, 1953 by a resolution of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Vinnytsia region. The denunciation of the head doctor was written by the school's physical education teacher Ivan Vasyliovych Levkov, who said: “All Jews are enemies.” B. Gelvarg was born in 1906 in the village of Rayhorod, Vinnytsia region. He worked as a carpenter in the Bar sugar factory from 1928-1929, after which he graduated from the Odessa Medical Institute. He held a position in the army from 1935 as a military doctor of the 3rd rank. After the war, 1944 to 1946, he worked as the chief physician of the Bar District Hospital. From 1952 to the beginning of 1953, that is, before his arrest, he worked in Kopaigorod. After the arrest of B. Gelvarg, Horobeiko worked as the chief physician of Kopaigorod.

|

|

Warrant for the arrest of chief physician B. Gelvarg, February 1953

Ministry of State Security

Warrant # 2362

February 18, 1853

Given by Vinnitsa regional department of the Ministry of State Security

To Maksimov

For making arrest and search of Gelvarg

Arrest is sanctioned by acting regional prosecutor of Vinnitsa region Potaruk

Kopaigorod, Kopaigorod district Vinnitsa region

The head of the office of the ministry of state security Colonel Kasatkin |

At that time, almost everyone knew about the Doctor's Plot, the killers in white coats. Hospitals and medical offices, known as polyclinics, suddenly became empty and quiet, as if all the patients had already been cured. Many doctors were Jewish, and if they could harm Stalin, what hope did a simple peasant have? After Stalin died, on March 5, 1953, the new ministers declared that the whole issue was fabricated. The doctors were falsely accused of being the enemies of the people.

At various times, Jewish doctors worked in the Kopaigorod hospital, pharmacy, and polyclinic, including Herzenstein, Berenstein, B. Buchman, Gitelman, P. Belenka, and nurse Zh. Degen. M. Segal and my sister Galina worked in the laboratory, Lindvor in the pharmacy, Y. Zhivylko (officer, war participant) has been working as the chief accountant of the hospital for many years, P. Kats as a typist secretary, R. Kasyanskyi as a dentist, and others. Other Jews in Kopaigorod worked as watchmakers, tailors, hairdressers, salesmen, shoemakers, managers of sausage and dairy shops, a soda shop, director of a teahouse, store managers, musicians, doctors, teachers, and soldiers. Most of the surnames on street signs and monuments on the square were Jewish.

The surnames of some families living in Kopaigorod were Kuperstein, Leyser, Katz, Gedal, Rosenblit, Groysman, Milman, Grinstein, Herman, Fishilevich, Weksler, Wasserman, Hytsilevich, Farber, Kraemer, Katsura, Borukhovich, Spector, Segal, Steiman, Binstock, Goldman, Gelin, Braverman, Abramovych, Vynokur, Libman, Okopnik, Roizen, Badni, Schwartz, Holoborodky, Koifman and many others. There were probably more than a hundred Jewish surnames. This was our Jewish history and our life. Familiar faces, partially forgotten names, and various stories pop up in my dreams and disturb me. In our town, Froim liked to say that tomorrow God will give a day and provide food, and he also added in Ukrainian: “And after me, it may be the end of the world.”

In the post-war period, there were many small enterprises in Kopaigorod. A bakery which later expanded, a sausage shop, and a lemonade production shop (citrozech) were built as part of an industrial complex. There was a woodworking plant, a rural consumer association (Silpo), a land reclamation station (PMK-207 ), inter-collective farm development, communal farm, department of agricultural machinery, section of the Bar water channel, and later, independent enterprises of various shops. People also worked in a high school, a dormitory, a polyclinic, a hospital, two libraries, a cultural center, and a cinema.

|

|

| Jews of Kopayhorod, 1950's |

There were many small businesses in the town, including an exchange office from Shargorod Industrial Complex. Lipkopker was in charge of it. This office accepted sunflower seeds, and in exchange they gave out oil and cake. Sometimes wheat was accepted here in exchange for flour.

There was a district newspaper, Lenin's Way, and from 1956 to September 1959 it was called Leninska Zorya (Lenin's Dawn). This newspaper at number 110 stopped being published in connection with the liquidation of the district.

A water pump house was initiated in 1967. The Bar Water Canal, and its manager Sirota Naum Itskovich, contributed to the organization of the area's water supply, with the support of the village council and the residents of the town. The entire network is approximately 19 km.

Once, while talking to local residents, I heard: “Since the Jews left the town, it has lost its flavor; they were good people. When there were Jews and we lived easier with them.” Immediately after the liquidation of the district, Jews left Kopaigorod. Some were transferred to other districts of the Vinnytsia region. Some went to another city by choice. But mass emigration began in the 1990's after the collapse of the Soviet Union, mainly to Israel. With the disappearance of the Jewish residents, the town lost both its external and internal appearance. There is no one left here from that friendly and numerous Jewish community. The people who contributed to that unique main street experience have moved around the world or gone to another world quietly, imperceptibly, like water through sand. Some are dead and others are far away.

Officially, there was no longer a synagogue after the war. Jewish believers gathered in Rebbe Srul's house where they held daily and holiday prayers. Of course, these gatherings were illegal. These congregants entered Srul's house one by one to pray. And we, the children, were told by the adults, that if a “mench mit a kneplach” (a man with buttons - a policeman) appeared, we should report it to them. When a law enforcement officer detected an illegal gathering he expected the reward of a promotion in rank. After the prayers, candy-cockerels and cookies were waiting for us.

I think that the local authorities knew about the illegal prayer house but pretended not to notice. I remember a crowd of elderly Jews in the courtyard of the house of prayer, the evening before the holiday of Rosh Hashanah looking up to where Srul was standing in the viewing window, looking up toward the gray-green dusky sky. There was a tense silence in the crowd, and then, the Rabbi saw the first star. Srul made intense holy sounds that rose to heaven from the twisted shofar. Women gathered for prayers separately in another house, led by Ester Hershkovich (Iosevych), my grandmother's sister. There were no open synagogues in the days of my childhood. Everything Jewish was stuffed into a corner, but all Jews knew exactly when the Jewish holidays began. I remember that the Jews always asked Ester to tell them the dates of this or that holiday: Purim, Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Shavous, Sukkot, etc. Of course, they started preparing for the holidays in advance. That's how it was established. Jewish traditions were carefully preserved and remained forever in the soul.

Back in my school years, I often saw Ester praying, holding a thick, tattered book. I now realize that it was a Siddur, a prayer book. I once asked Ester during her prayer, “Vus di tist?” - (What are you doing?). She put her finger to her lips for me to be quiet. When she finished praying she said: “Mayn kind, ih ob gedovnt, mi turnit redn, ven mi dovnt”, (it is not not allowed to speak during the prayer). I heard many sayings in Yiddish from Ester. She loved me, Galya and Yuchym very much. On long, winter evenings Esther often sat down with a large sieve on her lap, and a paper bag with goose feathers next to her. She sorted fluff and torn feathers from waste, into the sieve. After she collected the required amount of fluff, she made a pillow. Many elderly women were engaged in such work. Over the years, the Soviet authorities practically supplanted religion and the Yiddish language, but the traditions survived, and the language, as it turned out, was also passed on.

In his report for 1970, the Commissioner for Religious Affairs in Vinnytsia Region wrote that there was an unregistered religious community in Kopaigorod that numbered 20 people. I believe that the number was higher. Where did the number in the report come from? When G-d threatened to destroy Sodom and four other cities, Abraham pleaded with God to not do it. Abraham hoped to find fifty righteous men in those cities. From this, the sages concluded that a minyan is 10 people (5 cities - 50 people). That is, as long as the minyan gathers in the town and the Torah is read, this town is under the protection of G-d. Accordingly, the commissioner for religious affairs called the rounded numbers by towns.

In Kopaigorod, the Jews were kind, decent, life-loving, carefree, and knew how to laugh at their own shortcomings. They were faithful to their traditions, the testaments of the Torah. And Kopaigorod itself was a kind of paradise, surrounded by forests and gardens.

In conversation among themselves surnames were not used, but people were addressed by their nickname or first name, and took into account a person's profession or characteristic features. For example: Rosy di longi (Long Rose), Srul-goi (Srul-gentile), Haskel-shister (Haskel-shoemaker), Trugervoser (water-carrier), Elya-carpenter, Yankel-shoykhet (Yankel-the butcher) and many other nicknames echoed around.

Even people from different towns had a general nickname. For example: Chernivtsi yolds (slackers), Mogilev fresers (eaters), Muraf shlepers (beggars), Shargorod gonuvn (thieves), Zhuryn mishigums (fools), Zhuriner slasar (Dzhuryn locksmith), Verkhiv tsig (goats). But the residents of Bershad were called Bershad talitniki (prayer covers), as a sign of respect for the Hasidic rabbi Raphael of Bershadsky, well known by Jews in Ukraine. During the time of Tsar Alexander I, in 1804, the Jewish Committee ordered, in the Regulations for Jews, that every Jew must have or accept a well-known hereditary surname or nickname. This was enacted to make it easier for officials to identify people for the census, taxation and the conduct of court cases. This name was to be preserved in all acts and records without any change, with the addition of the faith of a child at birth.

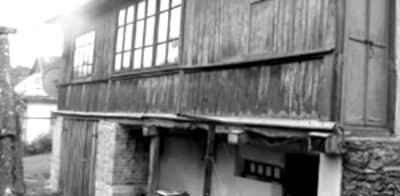

Jewish houses in the town were crowded together in such a way that it was difficult to walk between them. These Jewish walls remembered many joys and sorrows, love and happiness, and most importantly, the Jewish spirit lived in them.

I will repeat that there was no such place in Kopaigorod where Jews did not work.

Let's start with the post office. My father worked as a head of the post office, V. Groysman worked at the Union Printing Office, Sh. Bogorodchyn and L. Bogomolnyi at the telephone and telegraph station, D. Schneiderman as a postal operator, M. Bogorodchyn as a postman, and A. Katsura worked as a fitter. Ya. Braverman worked as an inspector in the finance department, R. Spektor was in charge of the canteen, and E. Katsura was in charge of the canteen buffet. Dina Gelin worked in a bookstore. Lindvor worked as a vet doctor, and his wife ran a pharmacy. Chief of the exchange office was Lipkopker. J. Farber worked as a photographer. Sewing was done by: Ya. Zus, M. Milhiker, B. Fishilevich. S. Fishylevich worked as an accountant in the bank. The following people worked in trade: I. Belenkyi, A. Getsilevych, and her husband worked as the head of the Shipynetsk wholesale trade, M. Fishilevich, M. Abramovych, Groysman, Shafir, and also Pesya, Roza, Raya, Manya - that's what the buyers called them. M. Borukhovich sold gas pipelines and filled siphons. V. Vynokur worked as a foreman at a sausage factory, Fishl Herman worked at a silk factory, and K. Braverman worked as a teacher in a kindergarten. S. Rosenblit was in charge of the bakery, D. Kramer worked as an art director in the cultural center. In the 1950s, V. Horodetsky worked as the director of the regional consumer union, and Seltzer was the senior accountant. I can't remember all of them.

|

|

| A Jewish house with a gallery on the second floor |

|

|

The team of the communications department. My father, B.M. Kuperstein, head of the department, is on the left.

Photo from May 1, 1975. |

I also remember elderly Jews: the watchmaker Uncle Shmil, the talkative Uncle Haim, the tailor Yankel and others. Uncle Haim was a scavenger. He traveled around the villages, buying “olte shmotes” (old things). He had one horse and a cart. Sometimes he would ride the children on it, and the children would help him collect his “shmotes”. For this, he gave them rooster lollipops on a stick and balls with whistles. The children ran down the street, happily enjoying these wonderful treats. It was a Jewish street on which more than one generation grew up. It was a Jewish life, poor, but good and friendly.

|

|

| M. Milhiker at the workplace with his sewing machine. He was a good tailor. |

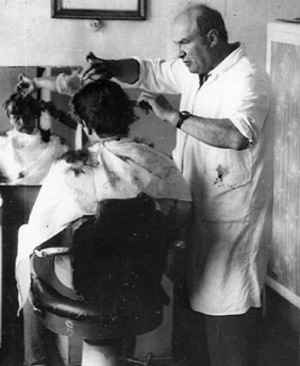

Only Jews worked in the barber shop: A. Schneiderman, Shor, Ostrovsky and two others. After a shave or a haircut they always politely asked the client which cologne they preferred to freshen up: “Shypr”, “Triple cologne” or “Floral”. Hairdresser Sasha would put the scissors aside, take a spray bottle from the table and, pressing the rubber bulb, sprayed “Shypr” on the satisfied client. The client thanked Sasha, paid forty kopecks and left. After resting for five minutes, Sasha would start a conversation with the next client. The conversation was often like this:

- Sasha - Go, sit in the chair, don't make my nerves hurt.

- Client - I'd like kanadka (a special style of haircutting)

- Sasha - I know. Do you think that Oleksandr Moiseyovych is already so old that he has forgotten how he cuts his clients' hair?

Each hairdresser had his regular customers. It was not necessary to always ask the client what haircut he wanted. There was only one answer to such a question: “As usual.” When small children were there for a cut, they were placed on a special chair where the height could be adjusted. The children were spoken to in an adult manner, and they immediately forgot about tears and fear. Parents usually did not give their children money in advance for haircuts. When they were finished, the children told the barber that their father will come on Friday for a shave, and to pay. The hair salon was a kind of information center about the lives of customers. While cutting, the client told various stories about himself, his neighbors and much more. Once, the musician Greenman came to the barbershop. He waved his hands, telling how he conducted at school and how successful he was, until Sasha wrapped him in a barber's cape and worked on his hair. I will only tell you that his black hair was not natural looking. “Here you are a person of art and I am a person of art”, said Sasha, clicking his scissors. Cutting hair, so to say, is a whole symphony. Each strand, like a note, must be in its correct place.

In 1919, the commander of the convoy detachment of the Ukrainian People's Republic in Kopaigorod, decided to give the soldiers a “herring” haircut. To accomplish this, he gathered all the hairdressers of the town. They were mostly Jews, and had a good understanding of the business at hand; after all, it was necessary to cut everyone's hair quickly. Of course, this did not increase the combat power of the army. The commander simply did not want his soldiers to differ in any way from the soldiers of Zaporizhzhya Sich Cossacks.

|

|

| This is roughly what a barbershop was like in the 1950's. Haircut kanadka. |

Each craftsman had his own set of razors which were stored in special cases. Razors were sharpened on special leather belts. The shaving foam was whipped in special metal glasses. At the end of the 1960's, craftsmen already had electric clippers, but mechanical clippers had not yet lost their relevance.

|

|

| The Communications Department, and my father standing with the postmen before delivering the mail to the townspeople |

There were many Ukrainians living in the town of Kopaigorod. In addition to those I have already mentioned previously, more names include: Artura Sydorivna Bezbakh, who worked as a notary in the Kopayhorod notary office in 1953–1959. Artura Sydorivna's husband, Vasyl Ivanovych Sinytsia, a veteran, worked as an investigator in the prosecutor's office. Ukrainians, Jews, and Poles worked side by side at various enterprises of the town, helping each other in their work and everyday life.

Lifestyle and Traditions

On warm evenings, especially on Shabbat, Jews, festively dressed, walking and talking in Yiddish, gave Kopaigorod a festive and business flavor. They were, in fact, the masters of the central street of the town, intelligent people with a good sense of humor. The Jews seemed to be the highest stratum of the educated and respectable part of the Kopaigorod community. After more than sixty years, I see familiar faces, someone's smile and someone's mysterious eyes from under huge eyelashes and hear a familiar dialogue:

- Hello, and how are you?

- And you?

- But we were the first to ask for that!

- And we are so modest that it is better that we answer last!

For a true artistic description of the way of life and daily life of the Jews, one must have the talent of Sholom Aleichem or Mykhailo Zhvanetskyi (Ukrainian Jewish writer and humorist).

People bought ice cream by weight in paper cups with a flat wooden stick, and drank soda water. Rudy sold this, from his cart. He had a teaspoon with a long handle for stirring the syrup. We always stopped to look at this unique spoon. His sparkling water foamed and poured beautifully. There was strawberry syrup that tasted like strawberries, and the cherry syrup smelled like cherries. The whole process began with a slippery oilcloth full of syrup which attracted wasps as well. When Rudy's fingers touched the butterfly valve a thin stream of syrup poured into the glass, followed by a stream of carbonated water. There was always a queue at his slaughterhouse where he sold the ice cream.

- For us, well, please give us double syrup, - said the customer.

- What happened?, Rudy asked. - Any event? So why not with a triple?

And he poured enough for a triple, but charged as if it were a double.

Whole families lived on the same street in Kopaigorod: from elderly family to the youngest grandchildren. Houses were built rather close. One needed only to shout someone's name near the house of one of the relatives to call them. The relatives would already know the reason why you were looking for them and not at home.

It wasn't possible to visit all of your friends in one day. It just took too much time at each visit. You would be thoroughly questioned about all of your family in every house: about those who were alive and those who died. The interrogations usually lasted for two hours.Then the guest became the listener, and the guest had to hear all they wanted to know, or didn't want to know about the host's family. You certainly wouldn't be let go without being fed lunch or dinner. Refusals were not accepted, even if your stomach hurt and you couldn't put anything else in your mouth. You might have been treated to jelly or “esek fleish” (sweet and sour meat). Imagine if someone didn't know how to cook delicious food. Then the guest who had to try it could claim the title of hero.

At first, food was cooked on a primus stove, which required kerosene gas and fire extinguishers. Electricity was supplied in the evening, when it got dark, until midnight. Only since the mid 1960's, after Kopaigorod was connected to the unified energy supply system, was there light around the clock.

After the liquidation of the district, the post office was moved to the former premises of the bank. And so it happened that now we began to live near the post office, and the electricity in our house was obtained through the post office. It was wonderful to have light around the clock. The post office had its own diesel power plant, which provided electricity for communication all of the time.

There were all sorts of electric appliances: electric stoves, irons, electric spiral water heaters used in a bucket for laundry, and homemade or store bought electric heaters that made the red and white dial of the electric meter spin at higher speeds. Periodically, clerks from the electric company came to take meter readings, after which large electric bills were issued. It wasn't difficult to break the dial on the meter. One needed only to place a small piece of photographic film into the counter - pushed through the glass of the window, and the dial stopped. One acquaintance demonstrated how he made the dial of his electric meter rotate in the opposite direction. There were not many such skilled craftsmen, but many knew how to simply negotiate the electric meter. And they used this technological gift. The state deceived the people, and the people, whenever possible, deceived the state. And so, they coexisted.

The inhabitants of the towns were allowed to use only a certain designated number of electric light bulbs. There were no meters at first, and the capacity of the power plant was limited. That is why the theft of electrical energy began in that period. Some residents started using household electrical appliances. People screwed an adapter into the original electric cartridge. It was hard to find such a device in a small town, so local craftsmen sometimes made adapters from other parts. The people called such a device the Russian word, “Cheater”.

Both electric stoves and electric irons, the most common household appliances at that time, had coils that burned out periodically. You could carry a stove or an iron to the workshop, or you could buy a suitable spiral to put it in the place of a burned one yourself. Asbestos was used in these devices as insulation. At that time, no one had any idea about the health dangers of using asbestos. My father and I always repaired these devices ourselves; we always had a spare coil at home.

I began to understand Yiddish as I heard it around town. Even though I didn't really know much, I could repeat whole sentences. When I was older I began to learn to read and write Yiddish on my own. My parents always spoke in Yiddish when they didn't want us to understand what they were talking about. Yiddish was heard at home and on the street. The boys, playing on the street, communicated in Ukrainian and Russian, occasionally inserting Yiddish words to emphasize our expressions.

When I turned thirteen I had a bar mitzvah ceremony. According to the laws of Judaism, when a Jewish boy reaches the age of thirteen he becomes responsible for his actions and he is called to the Torah as part of the ritual of the Bar Mitzvah. For a girl, the age of maturity, or Bat Mitzvah, is reached at the age of twelve. Up to the age of bar or bat mitzvah, parents are responsible for the child's religious observance. Upon reaching bar or bat mitzvah age, children become responsible for their own ethical and ritual observances, and are accepted as participants in the life of the Jewish community. There was a time when these rules were strictly followed.

I think that a visiting rabbi from Zhmerinka conducted my bar mitzvah ceremony, although I don't remember exactly. Several children gathered with us, with whom the rabbi performed this ceremony. It was a big holiday for us. The rabbi made a bracha, a blessing, for us, and said to my parents, “God grant that everyone will see a lot of “naches” (happiness) in him. May God give him health and a good wife.” Of course, everything happened secretly so that no one knew outside of our little gathering. After all, the authorities banned various religious ceremonies.

This is all from our life, from those distant and recent times.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Kopaihorod, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Dec 2023 by JH