|

|

|

[Page 375 - Yiddish] [Page 39 - Hebrew]

By Yosef Lifshitz

Text translated by Norman Helman z"l

Yiddish captions translated by Jerrold Landau

2. The Socialist Movement in David-Horodok in 1905

Unfortunately we have no material to enlighten us about the year 1905 in David-Horodok. We have no alternative but to draw on the memories of people who had not even taken an active part in the happenings of that stormy epoch.

From these memoirs, we learn that in 1905, a small group of the Bund was organized in David-Horodok under the leadership of the well-known A. Litvak, a Bundist who was rumored to have been banished to David-Horodok.

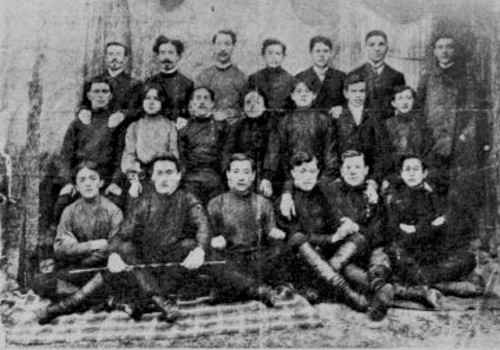

There was also a group of Socialist Territorialists. Concerning this group, we even have a historical reference. In the American Forverts [The Jewish American Forward newspaper] a picture was printed of 20 members of the David-Horodoker Socialist Territorialists (the picture is printed in our memorial book.)

The Poalei Zion [Workers of Zion] party also existed in David-Horodok at that time.

According to these stories, all of these socialistic movements were embraced by a great number of the youth. For a certain period, they were the rulers of the town. They had developed a

[Page 376]

self-defense organization and had weapons. They demanded a 12-hour work day. The laborers themselves did not want that “little” work but the revolutionaries would come and force them away from their work. There were cases where the children revolutionaries would come to their employer parents and take away the last workers. Aside from this, the revolutionaries were occupied with the distribution of wealth and self-education.

With the downfall of the revolution, all these organizations dissipated in David-Horodok. Some individuals were arrested and sent away. Many fled to America. The remainder left town during the period of danger.

In reference to this, it should be noted that after the Kerensky revolution of 1917, leftover members of Poalei Zion reestablished their organization. All the old revolutionaries again became very active and devotedly participated in the work. They tried to organize all the workers and sympathizers and they were very active.

Their activity was widely diversified: organizing readings, night classes, drama circles, a library, cooperatives and managing professional movement.

In those days the town was divided in two: the General Zionists and the Poalei Zion. At the election of the Constituent Assembly in Russia, the General Zionists received 120 more votes than the Poalei Zion – 740 to 620.

With the turnover of David-Horodok to the Bolsheviks, the situation changed. A few of the Poalei Zion leaders joined the Bolsheviks. The great majority of the leaders along with the entire membership did not follow them. They died off politically. From the entire powerful Poalei Zion organization of those days, there remain only memories.

|

|

[Page 376 - Yiddish] [Page 41 - Hebrew]

3. Cultural Institutions

As indicated in a previous chapter, David-Horodok was culturally under the influence of Lithuanian Jewry. The Haskalah [Enlightenment] movement had permeated the town in the last century through the boys who had gone to Lithuanian yeshivas and especially through the Jewish merchants of David-Horodok who encountered in their travels the new winds blowing in the larger Jewish centers. They were also the ones who felt that their practices required that they give their children a broader and more general education that that given by the cheders and yeshivas.

To that purpose, A. Y. Shafer, M. Y. Lifshitz and others brought the renowned Y. S. Adler to teach in David-Horodok. He introduced a new instructional system and he laid the foundation for a modern and Zionistic education.

The other teachers in town attempted to adapt to the new times and they began to teach Hebrew in Hebrew. These included S. Leichtman, S. Zago-

[Page 377]

|

|

-rodski and Y. Begun who were not the most eminent of the Jewish instructors but they were teachers who felt that they had a nationalistic and Zionist mission to educate a new Jewish generation. They were the carriers of Zionism in those days.

The elders also tried to open a high school in town. This was eventually opened as a government school. That was the town school in the Russian language which did a good job in helping the youth get into the intermediate and higher institutions and thereby acquire a higher education.

After the February Revolution in 1917, a Hebrew school was opened in David-Horodok under the directorship of the teacher Manevitz. With the assistance of teachers Yosef Begun, R. Shafer, Y. Kashtan and Y. Margolin, the school was established at a very high level. The school fulfilled a double purpose. It taught the children and, at the same time, it was a center for Zionist activities and national consciousness.

The Hebrew school existed until 1920. During the stormy war years

[Page 378]

when David-Horodok was passed from hand-to-hand, it was impossible to carry on a normal educational system.

After the Polish-Bolshevik War, when normal life was restored in the town, the first concern was to set up the school.

|

|

In 1924, a Hebrew Tarbut [culture] School was founded anew under the direction of R. Mishalov.

There is not enough space in this book to detail in full the blessed activities of this Tarbut School in David-Horodok. It started with three classes and in time, it became a seven class school and one of the best in Poland. Until its closing in 1940, there were eleven ceremonies which graduated hundreds of children.

It was not easy to strengthen the Tarbut School to a point where it could stand safely on its own feet. The school did not get any subsidy from the government or the municipal agencies. The various expenses of the school as such were laid on the shoulders of the parents of the students. The teaching personnel existed only on their wages from tuition. Remembering the grave poverty which ruled the town, we then begin to understand the great difficulties with which the school struggled every moment. It was a credit to the remarkable commitment of a group of concerned individuals in the town to the loyalty of the teaching staff and the principal R. Mishalov and to the national consciousness of the parents. The parents were almost 100% in sending their children to the Tarbut School despite the fact that they had to pay tuition when, at the town Polish government school, the studies were free.

[Page 379]

These three factors: the employers, the teaching staff and the parents, were responsible for the existence and the thriving of the Tarbut School.

The second director of the school, the teacher Avrasha Olshansky, elevated the school to such a high level that it became one of the best Tarbut Schools in all of Poland. After finishing the Tarbut seminar in Vilna, he first, as a teacher and later as director, devoted his entire energy and time to the school, leading it from year-to-year higher and higher. He was the one who, in 1931, founded the Bnei Yehuda [Sons of Judah] of David-Horodok, the Hebrew speaking youth of Poland.

Afterwards, the movement spread to other cities and towns in Poland but nowhere was it treated more earnestly than in David-Horodok.

It is worthwhile dwelling briefly on the Bnei Yehuda movement in David-Horodok. It began through the initiative of the director of the school, Avrasha Olshansky. He persuaded several school children that pupils of a Hebrew school who planned aliya to the Land of Israel ought to speak Hebrew not only in class but also at home and in the streets among themselves, with their parents, brothers, sisters, neighbors, friends and, in a word, with everyone. From a small group of children, the movement spread to all the school children.

|

|

[Page 380]

A child who had joined the Bnei Yehuda movement was obligated to speak only Hebrew at home, in the street or in the shop where he would buy a book. A Bnei Yehuda would always speak Hebrew to a Jewish companion. Understandably, at first, it was very difficult for the parents who did not understand Hebrew and it would often tax their interest but it was not long before the parents, the shopkeepers and the grown-ups in the street began not only to understand Hebrew but also began to answer in Hebrew.

Christian servants in Jewish homes also began to understand and speak Hebrew. Babies were taught Hebrew from the beginning.

Once David-Horodok was visited by Yosef Baratz. Before he came to town, he had heard the wonder of the “Tel Aviv of Polesye” as David-Horodok was called because of the spoken Hebrew. He could not believe that it was really true. To demonstrate to him that it was true, they took him out into the street. When he happened to meet a child, he would address the child in Yiddish expecting the reply would also be in Yiddish. No matter how many children he met, everyone replied in Hebrew.

A child who belonged to Bnei Yehuda always got a “5” (very good) for his grade in Hebrew class no matter how bright he was.

At first, the children organized a special intelligence unit whose task it was to verify that the new members of the Bnei Yehuda were keeping to their oaths to speak Hebrew exclusively. The intelligence officer would sneak into the new member's home and lay under a bed for hours in order to ascertain that the member was keeping his oath.

The Tarbut School existed until the onset of World War II. When the Soviets entered David-Horodok at the end of September, instruction in the school began once again but the language was Yiddish and not Hebrew.

An unforgettable moment occurred at the beginning of that schoolyear. The director, Avrasha Olshansky was forced, under the dictate of a Communist activist who himself was a graduate of that school, to assemble all of the children. Sobbing spasmodically, he announced that the school would no longer teach Hebrew but only Yiddish. The Communist activist then gave a lecture that the children had been duped in the past. He wanted to convince them that their Hebrew language was the language of the Jewish counterrevolutionaries.

Avrasha Olshansky, until then, had been the devoted and faithful father of the school but now he could no longer bear teaching there. He could not ethically tolerate the change. He and his wife, who was also a teacher, moved to Bialystok. He, his wife and children met their death at the hands of the Nazi murderers. Honor to their memory!

[Page 381]

Through the initiative of the same A. Olshansky, a course in Tanach [Hebrew Bible] was initiated. It went under the title of “Every Day a Chapter of Tanach.” This course was intended for the grown-ups in David-Horodok. These lectures were extremely popular. The course was attended mostly by the older youth and the adults. The lectures would pack the large hall in the school. The people who attended the lectures were from all social levels and from all political directions, both religious and freethinkers.

Teachers with a variety of beliefs taught the Tanach. A rabbi would teach and give an overall religious interpretation in his lecture. A maskil (adherent of the Haskalah) would lecture, explain the chapter with the use of new interpretations. There was a lecture from a member of the free atheistic circles who interpreted the Tanach from a purely historical-cultural viewpoint.

It was most interesting that each lecturer's special point of view was listened to with tolerance and patience.

These lectures began in 1937 and continued until the beginning of World War II.

In 1927, the Mizrachi [religious Zionist movement] initiated a religious Yavne school. This school did not exist for long having closed after only two years.

Besides the schools, there existed well-organized libraries in David-Horodok.

The teacher, S. Zagorodsky organized a library for children and school youngsters even before 1905.

In 1917, the Zionist organization in town founded a library which developed well. Unfortunately it was not active during World War I.

Following World War I, the libraries in David-Horodok developed vigorously. In 1925, the Poalei Zion founded a library named for Y.L. Peretz. In the last years prior to World War II, this was the only active library for adults in the town. There was a large library for the students at the Tarbut School.

[Page 382]

Publications with Zionist and literary themes always had a wide audience. There were also self-education groups in town sponsored by the various parties and youth movements.

David-Horodok also had a long-standing amateur drama group which would give performances from time-to-time. There had long been an inclination towards theater and acting in David-Horodok. Even in the time of the 1905 revolution, such amateurs as I. Opingandin, Y. Gotlieb and Helman would excel in readings from the masterpieces of Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, Bialik, Frishman and others.

Later, a group of amateur artists were trained and they gave two or three performances each year for the Jewish populace. The most outstanding among them were the dentist Edel, Zelda Finkelstein and the midwife Kreinin.

|

|

Translator's note: one of these years is off by one, as Purim 5699 would be in 1939 |

[Page 383]

After the 1917 Russian Revolution and later after the Russo-Polish War, the drama circle developed somewhat further. Fresh forces arrived and they would give a serious performance from time-to-time. The proceeds of the performances were for various charitable purposes. At times, they would use a percentage of the revenues for a variety of purposes.

In praise of the drama circle, it must be said that the amateurs had little interest in how to divide the money. They were only interested in artistic success.

In 1936, another youthful amateur group was founded. They gave several successful performances. Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War II ended the activities of both drama groups. It should also be mentioned that the children of the Tarbut School would give a successful annual performance under the leadership of their teachers.

|

|

David-Horodok also had a sport club, Hakoach [The Strength] which developed a very good football [soccer] team. The football team competed for a couple of years but it was disbanded after their best players made aliya to the Land of Israel.

|

|

Seated (from right to left): 1. Shmuel Papish, 2. Chaim Branchuk, 3. Reuven Mishalov, 4. Unknown, 5. Moshe Erlich Standing: 1. Yosef Begun, 2. Abramovitz, 3. Unknown |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Page 45 top - in the Hebrew section] |

|

|

[Page 45 bottom - in the Hebrew section] |

[Page 384 - Yiddish] [Page 46 - Hebrew]

4. The Orphanage

David-Horodok was ruined and impoverished after World War I. The Joint [American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee], which had begun its aide activity throughout Poland, also opened a branch in David-Horodok. One of the Joint's most important accomplishments was the founding of an orphanage in the town.

There were many orphans in town. There were 32 orphaned children up to the age of 14 who were kept in the orphanage which was founded in a comfortable dwelling with three bedrooms, a large dining room which doubled as a lecture hall and a large courtyard where the children played a variety of games. The orphanage was well-equipped with such items as comfortable beds, good bedcovers and a sufficient quantity of food and clothing. The food was good and the children were well fed and appeared healthy.

The entire maintenance of this house was paid for by the Joint. The local people could be of no assistance except for supplying teachers who worked without pay.

That was the situation until the Bolsheviks recaptured David-Horodok during the Russo-Polish War. Then there was a radical change. The management of the orphanage was transferred to a branch of the social service department of the Revkom [revolutionary committee]. They gave much advice but little practical help. There were no food reserves in town. The children became hungry and began to scatter.

When the Bolsheviks left town, they took the entire inventory of the orphanage despite the protests of the David-Horodoker Jews.

After the Russo-Polish War, all efforts to reestablish the orphanage were unfortunately unsuccessful. Instead, an orphans' committee was founded which undertook to place the orphans in homes.

The chief priority was to enable them to learn a trade. Through the committee's efforts, the orphans were well cared for in private homes.

The money to support the work of the committee was raised by selling flowers [“flower days”], special campaigns and proceeds from performances of the drama circle. The main reason that the committee was able to exist was due to the support it received from the David-Horodoker Women's Committee of Detroit.

This support was achieved through Yitzchak-Leib Zager who had personal family ties with America. Thanks to his concern, the committee received regular support from America throughout its existence.

The orphans' committee existed throughout the period of Polish rule in David-Horodok. In 1939, when David-Horodok was taken by the Bolsheviks, the orphans' committee was closed along with all other institutions.

[Page 385 - Yiddish] [Page 46 - Hebrew]

5. Bank and Credit Institutions

In David-Horodok as in all other Jewish communities, credit was a common problem. There were always Jews who needed cash for business purposes, for a child's wedding, to build a house or because of misfortune.

In by-gone days, there were the so-called usurers [the Yiddish word is vokhernik because payment was due each week] who would loan money on a pledge and for considerable interest. Each Friday, the debtor would have to bring the usurer both the principal and the interest. The usurer was usually an influential Jew with considerable authority in the community. If the principal and interest were not paid on time, he would not hesitate to keep a pledge which might have been as much as ten times more valuable than the borrowed money. Understandably, going to the usurer was a last resort when there was no other way out.

When loan and savings funds began developing in Russia, one such fund opened in David-Horodok and later, a second fund as well. These two funds had the same purpose but had different names. One was named after the bookkeeper, Shlomo Rozman's Fund and the other was named after the bookkeeper, Pinye Sheinboim's Fund. Many merchants had accounts in both funds.

The funds enjoyed the complete faith of the populace and were entrusted with their savings. As a result, the funds had enough cash for loans to those needing them.

In 1909, the larger businessmen in David-Horodok founded a Merchants' Bank under the management of Noah Grushkin. The bookkeeper was Meir Olpiner. The bank developed very well.

With the outbreak of World War I, all the financial institutions failed.

After World War I when David-Horodok went over to the Poles and normal life had resumed, another Merchants' Bank was formed in 1923 under the management of M. Kventy, and a People's Bank was founded in 1924 under the management of S. Papish.

These banks developed very well and they were a significant factor in the economic life of the town. There was also a charity fund in David-Horodok which gave free loans to small businessmen and handworkers.

The charity fund was managed by a committee headed by Y. Gotlieb. This committee would control the requests and set the amounts of the loans.

|

|

Seated (from right to left): 1. Mendel Reznik, 2. Pesach Pilchik, 3. Gevirtzman, 4. Yankel Volpin, 5. Shmuel Papish, 6. Chaikel Freiman Standing: 1. Yudel Shnur, 2. Moshe-Yitzchak Eisenberg, 3. Moshe Katzman, 4. Moshe Veisblum, 5. Unknown, 6. Unknown, 7. Unknown |

[Page 385 - Yiddish] [Page 48 - Hebrew]

6. Firefighters

One of the most useful institutions in town was the fire brigade which was 99% Jewish.

[Page 386]

David-Horodok, like most small towns, was composed of houses built out of wood and with thatched roofs. These often fell victim to fires. Fire, the unbidden and undesired guest, would pay a visit almost every summer and cause considerable distress. Homes were burnt as a result of a variety of mishaps: carelessness with fires, placing a hot iron outside, going out at night to the stable with a torch, throwing away unextinguished cigarettes, children playing with fire and arson.

Fire was a nightmare for the masses. Summer was the most beautiful and the most interesting time in the life of the town. However, it was often spoiled by the frequent fires. In many homes, they would pack up the valuables in summer and carry them away to one of the town's few brick houses which were fireproof. An alternative was to keep the valuables at home in packs which would be easy to remove in case of fire.

In order to fight this plague and even in former times, a firefighters brigade was established. The town administration then built a large station to hold the equipment and the water buckets. The town administrator levied a special chimney tax with which to finance the building of the station. The insurance companies also helped pay the expenditures.

Almost all the Jewish youth were enrolled in the firefighters brigade. They considered it a civic obligation to belong to the firefighters. Even though the Christian populace was in the greatest danger because of their thatched roof houses, only three or four were enrolled as firefighters.

In summertime, the firefighters would periodically hold drills. In the olden days, this was quite an event in the life of the town. Massey, the station watchman, would go around all the streets with a special bugle to signal that the firefighters should come out for the drill. The firefighters would put on their special uniforms and gather at the station which was in the center of the town. After a few callisthenic exercises, one of them was secretly sent out into the streets to pick out a house which was supposedly burning. He would then give a signal and they would begin to “extinguish” the fire. The firefighters would pick the house of someone against whom they bore a grudge. After the drill, the firefighters would have a beer.

After World War I, the firefighters brigade expanded. The town council allocated more money to enlarge the inventory and to teach the firefighters better techniques of extinguishing and especially containing the spread of fires. However, when a fire broke out during a wind or in the vicinity of thatched roofs, the firefighters were unable to localize the fire. That is what happened in 1936 when a fire broke out in the middle of the day in the Christian

[Page 387]

part of town. One third of the town, along with the Greek Orthodox Church on the hill, burnt down.

In the last years before World War II, the town administration directed the firefighters. The management remained in the hands of Jews. The most active managers were Y. Yudovitz and M. Rimar.

[Page 387 - Yiddish] [Page 49 - Hebrew]

7. The Municipal Government

The David-Horodok populace had the status of town citizens [called meshchane with more political rights than the typical peasants] since the time of the Czars. They would vote every three years for a town council consisting of three persons: an elder (starosta) and two assistants. One of the assistants was a Jew.

The election would take place as follows: each street voted for a representative and the street representatives would then vote for the elder and his two assistants. This election process was far from democratic and those who wanted to be elected took advantage of family ties, neighbors. For the most part, the Christians would be “elected” through a bottle of liquor, etc. – and anyone who brought more would be elected.

That is the way things were until the revolution of February 1917. Then the town council was enlarged. However, as a result of the stormy revolutionary times and the frequent changeover of ruling powers, these elections were also not very democratic. When the Bolsheviks appeared in town, they appointed a Revkom and the Poles appointed the town council. During the entire period that the Poles appointed the town council, the Jewish representatives were always the same: M. Lachovsky, M.Y. Lifshitz and S. Katzman.

The appointed town council managed the town until 1928. In that year, elections for town council were held throughout Poland and naturally in David-Horodok as well.

That was the very first democratic election for town council in the history of David-Horodok. The Jews took an active part in the election and it was a vigorously fought campaign. Eight Jews were elected representing 40% of the town council. They were: Dr. Zholkver, M.Y. Lifshitz, M. Lachovsky, Y. Yudovitz, R. Mishalov, S. Reznik, H. Zipin and Y. Lifshitz.

The hope that they could use the town treasury to support the Jewish institutions was shattered. Every proposal suggested by the Jews to give financial aid to the Tarbut School, the Jewish libraries or even the orphans' committee, were rejected by the Christian representatives and the one Pole who was the chief representative.

The only Jewish operated institution that received a subsidy from the town council was the fire department. This was because it served the Christian populace as well.

The town council did finance the Polish public schools in town, paved the main road and built the

[Page 388]

power station in 1929, providing light in the houses until midnight.

When the term of office ended for the town council, new elections were not held. The reactionary movement had strengthened in Poland and the government was not interested in new elections. The result was that an agreement was reached without an election and a new town council took office with only six Jews: Dr. Zholkver, Y. Yudovitz, M. Kvetny, D. Rimar, M. Lachovsky and S. Mishalov.

By then, the town council had no power because the actual town authority was the district administrator in Stolin.

During the scant two years (end of 1939 to June 1941) of the Soviet rule in David-Horodok, there was no elected town council. It was run by appointed Bolsheviks sent by the Communist party.

[Page 388 - Yiddish] [Page 49 - Hebrew]

8. The Kehila

Unfortunately, we have no reference sources on the activities of the Jewish kehila [community] in David-Horodok. There are no remaining books or documents either from the past or from the last years before the Holocaust.

There was an organized Jewish kehila in David-Horodok just as in all Polish-Lithuanian cities and towns. Until the last partition of Poland, the David-Horodok kehila was linked to the Pinsk Great kehila and they paid taxes to Pinsk.

We do not know how the kehila was organized and when it became independent under the Czarist authority. We know only of certain sources of revenue for the kehila, for example: the karavka [a special tax] on meat; the selling of yeast which the kehila gave as an exclusive concession to the rabbis and the chevra kadisha [burial society] which was supervised by the kehila. The chevra kadisha was a well-organized and closed institution in which membership would pass by inheritance from father to son.

The First World War abolished everything and the various kehila affairs were taken over haphazardly by individuals. One would take care of the bathhouse and the mikveh [ritual bath], another the poorhouse and yet another the cemetery.

The old cemetery lay at the edge of the Horyn River and the water would often wash away parts of this cemetery. Every year, they would have to spend money to repair the holy ground. The expenses were covered by the chevra kadisha who had their own special source of revenue.

There was no official town rabbi in David-Horodok. There were several rabbis in town, about four or five in number, each supported by its own circle which had given it its rabbinical chair. From time-to-time, there were conflicts between the various sides especially when it came to dividing rabbinical funds which flowed in from general sources.

[Page 389]

In 1917, after the Kerensky revolution, the first democratic election to the Jewish kehila was held in David-Horodok through the initiative of the Zionist organizations. However, this kehila could not accomplish anything because of the Bolshevik revolution and the disruptive transfer of power from hand-to-hand in war time.

In the first years of the Polish reign in David-Horodok, after the Polish-Bolshevik war, there was no Jewish kehila in the town. The nominated town council representatives served as semi-official agents of thekehila. These were: Moshe Lachovsky, Shlomo Katzman and Moshe Yehuda Lifshitz.

As a result of a Polish government decree, elections were held for the Jewish kehilas in 1928.

However, the election ordinances were quite reactionary. Only those over the age of 25 had voting rights and those over 30 only had a passive right. Women had no voice at all. The jurisdiction of the kehila was severely restricted so that it had no responsibilities except for rabbinical matters, the bathhouse and the cemetery.

In David-Horodok, where the number of rabbis was relatively not small, the elections caused disputes and discord. They did not even avoid slander to the government. People and lists were invalidated, and there was no shortage of disgrace and wrath. Meetings of the kehila became arenas for conflict and dispute. The battle surrounding the election of a chief rabbi for the city of David-Horodok was particularly harsh. Rabbi Shapira was the first chief rabbi.

Elections for the kehila took place twice during the period of Polish rule. The first time was in 1928. Meir Moravchik was elected as head of the community. Kaplinsky was elected head of the community during the second time in 1936.

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Davyd-Haradok, Belarus

Davyd-Haradok, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 Mar 2024 by LA